Abstract

An increase in prevalence of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter spp. in hospitalized animals was observed at the Justus-Liebig-University (Germany). Genotypic analysis of 56 isolates during 2000–2008 showed 3 clusters that corresponded to European clones I–III. Results indicate spread of genotypically related strains within and among veterinary clinics in Germany.

Keywords: zoonoses, Acinetobacter baumannii, animals, veterinary clinics, antimicrobial susceptibility, antimicrobial resistance, DNA fingerprinting, amplified fragment length polymorphism, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, PFGE, clones, Germany, dispatch

Within the genus Acinetobacter, A. baumannii is clinically the most relevant species, frequently involved in hospital outbreaks and affecting critically ill humans (1,2). The strains involved are usually multidrug resistant, which limits therapeutic options (3). Many outbreaks in Europe and beyond have been associated with the European clones I–III (4–6).

Nosocomial infection in veterinary medicine is an emerging concern. The role of acinetobacters in diseases of hospitalized animals is largely unknown. Recent reports have documented occurrence of or infection with Acinetobacter spp., including A. baumannii, in hospitalized animals (7,8). The internal laboratory records of the microbiology department of the Giessen Veterinary Faculty (Institute for Hygiene and Infectious Diseases of Animals, Giessen, Germany) noted an increase in antimicrobial drug–resistant Acinetobacter isolates. To assess the species and type diversity of these organisms, we investigated a set of isolates from Giessen and other veterinary clinics obtained during a 9-year period by a combination of genotypic methods and compared the isolates for their susceptibility to antimicrobial drugs.

The Study

The Institute for Hygiene and Infectious Diseases of Animals in Giessen receives samples for investigation from other veterinary departments of the university (mainly referral clinics) and from external veterinary clinics throughout Germany. During 2000–2008, Acinetobacter spp. were obtained from 137 hospitalized animals. From these animals, 56 isolates were selected for further characterization. The selection was made to reflect the diversity in epidemiologic origin of the collection regarding date of isolation, animal species, specimen, and veterinary clinic (82% from Giessen) (Table A1). Only isolates with possible clinical significance were included as inferred from the fact that they were the only or the dominating agent within the sample. Furthermore, according to data from the diagnostic laboratory, the selected isolates were highly resistant.

Confirmatory susceptibility testing of isolates was conducted by using the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute broth dilution method (9) (Table). For precise species identification, amplified ribosomal DNA restriction analysis was performed. By this method, the 16S rDNA sequence was amplified by using PCR, followed by restriction of the amplified fragment by 5 restriction enzymes: CfoI, AluI, MboI, RsaI, and MspI. The combination of electrophoretic patterns of the respective enzymes was compared with a library of profiles (10).

Table. Resistance profiles of 56 animal Acinetobacter spp. isolates for 19 antimicrobial agents, obtained by CLSI broth microdilution test *.

| Profile; no. isolates | Tested antimicrobial agents |

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxa | Pen | Ctn | Ery | Cli | Chl | Cst | Cvf | Amp | Amc | Tet | Enr | Orb | Dif | Kan | Sxt | Gen | Ipm | Amk | |

| 1; 1 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | I | R | R | R | R | R | S |

| 2; 1 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | I | R | R | R | R | R | R | S | R |

| 3; 28 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | S | S |

| 4; 2 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | I | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | S | S |

| 5; 2 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | I | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | S | S |

| 6; 1 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | I | R | R | R | R | R | R | S | S |

| 7; 1 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | S | R | R | S | S |

| 8; 1 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | I | R | R | R | R | R | S | S | S |

| 9; 3 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | S | S | S | S |

| 10; 1 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | I | S | S | S | S |

| 11; 1 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | I | R | R | R | R | S | S | S | S |

| 12; 1 | R | R | R | R | R | R | S | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | S | S | S | S |

| 13; 1 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | I | R | S | S | S | R | R | R | S | S |

| 14; 3 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | I | I | R | R | R | R | S | S | S | S | S |

| 15; 1 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | I | I | R | R | R | R | S | S | S | S | S |

| 16; 2 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | I | I | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

| 17; 1 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | I | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

| 18; 1 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | I | I | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

| 19; 1 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

| 20; 1 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | I | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

| 21; 1 | R | R | R | R | R | R | S | R | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

| 22; 1 | R | R | R | R | R | R | S | I | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

*CLSI guidelines M31-A2 (9). CLSI, Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute; Oxa, oxacillin; Pen, penicillin; Ctn, cephalotin; Ery, erythromycin; Cli, clindamycin; Chl, chloramphenicol; Cst, colistin; Cvf, cefovecin; Amp, ampicillin; Amc, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid; Tet, tetracycline; Enr, enrofloxacin; Orb, orbifloxacin; Dif, difloxacin; Kan, kanamycin; Sxt, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole; Gen, gentamicin; Ipm, imipenem; Amk, amikacin; R, resistant; I, intermediate; S, susceptible.

Fifty-two isolates were identified as belonging to A. baumannii and 3 to A. pittii (Acinetobacter gen. sp. 3) (11); 1 with a yet undescribed profile remained unclassified. Amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) DNA fingerprint analysis was performed as described for confirmative species identification, for strain typing, and for clone identification (4,12,13). Briefly, EcoRI and MseI were used to generate restriction fragments that were selectively amplified by using a Cy-5–labeled Eco-A and an Mse-C primer. Amplification products were separated by electrophoresis and subjected to cluster analysis with the BioNumerics software package 5.1 (Applied Maths, St-Martens-Latem, Belgium). For species identification, isolates were compared with reference strains of all described Acinetobacter species included in the Leiden University Medical Center AFLP database (Leiden, the Netherlands). Isolates with profiles >50% similar were considered to belong to the same species (1).

To assess the type diversity of the organisms, isolates were typed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) (14) and by AFLP analysis. For PFGE, DNA was digested with the restriction endonuclease ApaI. Digitized profiles were analyzed with the BioNumerics software. For AFLP typing, a subset of 27 isolates was analyzed (Table A1). The profiles obtained were compared with each other and with those of the Leiden database, including those of the European clones I–III. A similarity cutoff level >80% was used to delineate members of the same clone and >90% to delineate organisms related at the strain level (4,12,13).

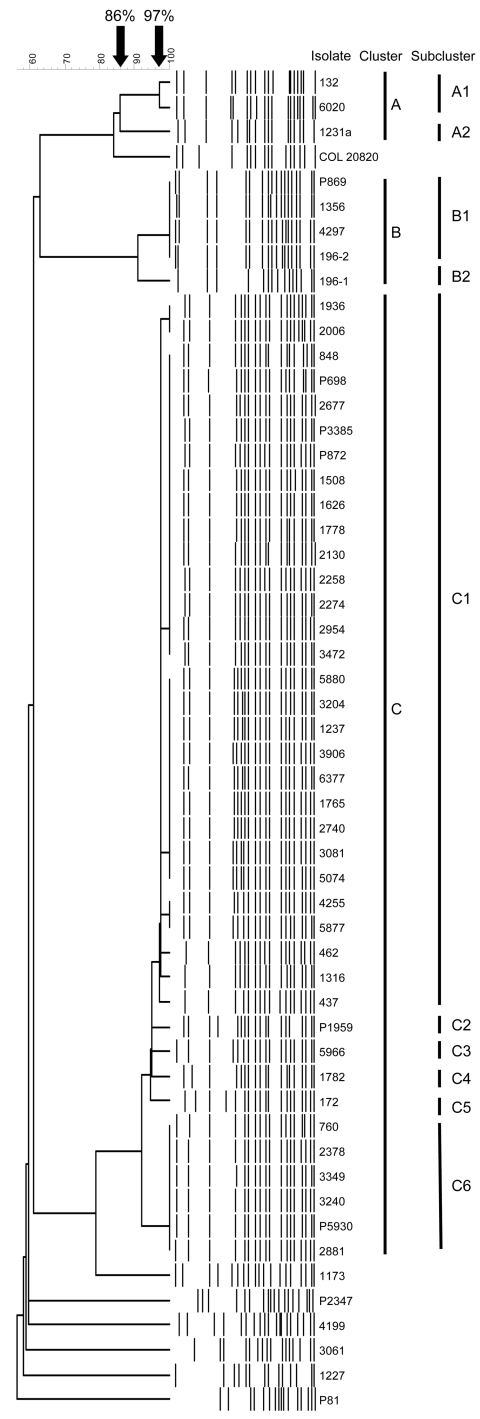

For PFGE, at a similarity level of 86%, 3 major clusters (A, B, and C) and 6 unique isolates were distinguished (Figure 1). Within major cluster C, 2 main subclusters (C1 and C6) and 4 single profiles (C2–C5) were observed at 97% similarity (Table A1; Figure 1). Despite some band differences, the patterns in major cluster C were strikingly similar. The maximum number of band differences in subcluster C1 was 3, which indicates that the organisms were genetically closely related. In subcluster C6, only minor differences in size of the fragments were observed (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Computer-assisted cluster analysis of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis fingerprints of 53 Acinetobacter baumannii and 2 Acinetobacter spp. pittii isolates. COL 20820 was used as the reference standard for normalization of the digitized gels (14).

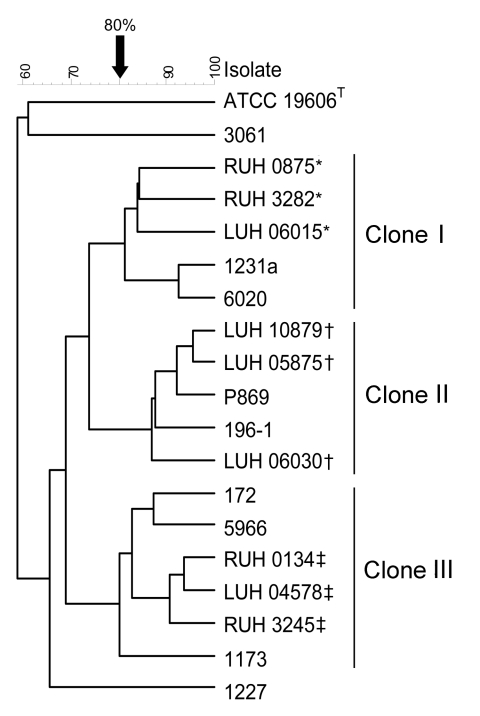

For AFLP, we investigated a subset of 27 isolates, including at least 1 isolate of each of the 16 different PFGE profiles and the 3 isolates nontypeable by PFGE. Seventeen AFLP types were distinguished at the 90% similarity cutoff level for strain delineation. Identification by AFLP showed full agreement with amplified ribosomal DNA restriction analysis species identification (Table A1). Comparison of isolates to those of the Leiden AFLP database grouped isolates with AFLP profile 8 (corresponding PFGE profiles A1, A2) with isolates of European clone I, those with profiles 10–16 (corresponding PFGE profile C1–C6) with clone II, and with profile 7 (corresponding PFGE profiles B1, B2) with clone III (Table A1). Examples are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Amplified fragment length polymorphism analysis of 9 animal Acinetobacter baumannii isolates belonging to the major pulsed-field gel electrophoresis types and 9 reference strains of the European clones I–III from the Leiden University Medical Center collection. *Reference strains of European clone I; †reference strains of European clone III; ‡reference strains of European clone II.

Conclusions

The occurrence of PFGE type C in different animals admitted to 3 different clinical wards of the Justus-Liebig-University Giessen over 9 years might indicate endemic occurrence of these organisms on these wards. Survival in the hospital environment (15), patient-to-patient transfer, and transfer from 1 animal clinic to another may have contributed to their persistence and spread. Because veterinarians, stockmen, and students rotate between the various clinics and departments, transmission by hands or equipment should be considered. Frequent transport of colonized animals to and from shared examination rooms, e.g., for computer-assisted tomography, might also have contributed to the chain of spread. Because type C isolates also were found in samples from animal clinics throughout Germany (Table A1), limited genetic variation in animal strains of A. baumannii also is possible.

AFLP data were, further to comparative typing of the animal isolates, also used to assess the relatedness of the isolates in our study to those of the widespread European clones I–III that represent genetically related but not identical strains that are frequently multidrug resistant and associated with epidemic spread in human clinics (1,4–6). Although not all strains were characterized by AFLP, we conclude by inductive generalization of results that the findings apply to all isolates of the PFGE types from which the organisms were selected. Thus, a large proportion of the animal A. baumannii isolates were genetically congruent with the European clone I, II, or III. Occurrence of such isolates in ill, hospitalized animals of various species might indicate that, as in human medicine, A. baumannii is an emerging opportunistic pathogen in veterinary medicine. The occurrence of clones I–III in animals and humans also raises concern about whether the organisms can spread from animals to humans or whether the animals have acquired the organisms from humans.

The occurrence of genotypically related, antimicrobial drug–resistant A. baumannii strains in hospitalized animals suggests that these organisms are most likely nosocomial pathogens for animals. If so, veterinary clinics face a great challenge regarding prevention, control, and treatment of infections with these organisms, similar to situations in human hospitals. Finally, the possibility of spread from humans to animals or vice versa requires special attention.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gabriele Köpf and Beppie van Strijen for excellent technical assistance.

The work was supported by a grant from the Akademie für Tiergesundheit e. V.

Biography

Dr Zordan is a research associate at the Institute for Hygiene and Infectious Diseases of Animals, Justus-Liebig-Universität Giessen in Germany. Her primary research interests include the significance of A. baumannii for animals and the epidemiology of this species in veterinary medicine.

Table A1. Origin and drug resistance profiles of Acinetobacter spp. isolates collected from veterinary specimens from Germany, 2000–2008*.

| Isolate | Species† | Isolation date | City | Clinic | Animal | Specimen | PFGE cluster | AFLP type | European clone‡ | Resistance profile§ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5880 | baum. | 2000 Nov 22 | Giessen | MVK | Dog | Feces | C1 | ND | ND | 3 |

| 5877¶ | baum. | 2000 Nov 22 | Giessen | MVK | Cat | Urine | C1 | 10 | II | 3 |

| 5966¶ | baum. | 2000 Nov 24 | Giessen | CVK | Cat | Urine | C3 | 10 | II | 9 |

| 6020¶ | baum. | 2000 Nov 28 | Giessen | MVK | Cat | Urine | A1 | 8 | I | 1 |

| 6377 | baum. | 2000 Dec 13 | Giessen | CVK | Cat | Urine | C1 | ND | ND | 3 |

| 132 | baum. | 2001 Jan 9 | Giessen | MVK | Dog | Pericardium | A1 | ND | ND | 13 |

| 1237 | baum. | 2001 Mar 12 | Giessen | CVK | Dog | Urine | C1 | ND | ND | 3 |

| 1765 | baum. | 2001 Apr 5 | Giessen | CVK | Cat | Urine | C1 | ND | ND | 3 |

| 2740¶ | baum. | 2001 May 31 | Giessen | CVK | Cat | Urine | C1 | 10 | II | 3 |

| 3906 | baum. | 2001 Aug 16 | Giessen | CVK | Dog | Urine | C1 | ND | ND | 3 |

| 4255 | baum. | 2001 Aug 28 | Giessen | CVK | Dog | Abscess | C1 | ND | ND | 3 |

| 5074 | baum. | 2001 Oct 3 | Giessen | MVK | Dog | Wound | C1 | ND | ND | 3 |

| 3204¶ | baum. | 2002 Feb 1 | Giessen | CVK | Horse | Tendon | C1 | 11 | II | 3 |

| P1697¶ | baum. | 2002 Mar 7 | Bad Marienberg | Private | Horse | Uterus | NT | 6 | NA | 17 |

| 1508 | baum. | 2002 Apr 2 | Giessen | AGVK | Cat | Urine | C1 | ND | ND | 3 |

| 1626 | baum. | 2002 Apr 9 | Giessen | CVK | Cat | Urine | C1 | ND | ND | 3 |

| 1782¶ | baum. | 2002 Apr 16 | Giessen | CVK | Cat | Urine | C4 | 11 | II | 3 |

| 1778 | baum. | 2002 Apr 16 | Giessen | CVK | Cat | Urine | C1 | ND | ND | 3 |

| P3385 | baum. | 2002 Apr 30 | Frankfurt/M. | Private | Dog | Bronchia | C1 | ND | ND | 4 |

| 2258¶ | baum. | 2002 May 14 | Giessen | CVK | Cat | Urine | C1 | 13 | II | 3 |

| 2274 | baum. | 2002 May 15 | Giessen | CVK | Cat | Urine | C1 | ND | ND | 4 |

| 2378 | baum. | 2002 May 17 | Giessen | CVK | Dog | Subcutis | C6 | ND | ND | 15 |

| 2881 | baum. | 2002 Jun 12 | Giessen | CVK | Cat | Urine | C6 | ND | ND | 14 |

| 2954 | baum. | 2002 Jun 14 | Giessen | CVK | Cat | Urine | C1 | ND | ND | 3 |

| 3081 | baum. | 2002 Jun 24 | Giessen | CVK | Cat | Urine | C1 | ND | ND | 3 |

| 3240 | baum. | 2002 Jul 3 | Giessen | MVK | Dog | Feces | C6 | ND | ND | 10 |

| 3349 | baum. | 2002 Jul 10 | Giessen | MVK | Dog | Duodenum | C6 | ND | ND | 14 |

| 3472 | baum. | 2002 Jul 18 | Giessen | AGVK | Dog | Vagina | C1 | ND | ND | 3 |

| P5930 | baum. | 2002 Aug 18 | Betzdorf | Private | Dog | Serum | C6 | ND | ND | 14 |

| P81¶ | gen. sp.3 | 2003 Jan 8 | Duisburg | Private | Dog | Nose | Un | 1 | ND | 20 |

| 172¶ | baum. | 2003 Jan 14 | Giessen | CVK | Dog | Urine | C5 | 13 | II | 5 |

| P872 | baum. | 2003 Feb 8 | Duisberg | Private | Dog | Nose | C1 | ND | ND | 3 |

| 848 | baum. | 2003 Feb 26 | Giessen | MVK | Dog | Bronchia | C1 | ND | ND | 3 |

| 2130 | baum. | 2003 Mar 19 | Giessen | Pathology | Cat | Urine | C1 | ND | ND | 5 |

| P1959¶ | baum. | 2003 Mar 20 | Heidelberg | Private | Cat | Thorax | C2 | 12 | II | 7 |

| 2677¶ | baum. | 2003 May 26 | Giessen | MVK | Dog | Urine | C1 | 14 | II | 3 |

| 4297 | baum. | 2005 Dec 15 | Giessen | CVK | Dog | Wound | B1 | ND | ND | 11 |

| 196–1¶ | baum. | 2006 Jan 19 | Giessen | MVK | Cat | Urine | B2 | 7 | III | 8 |

| 196–2 | baum. | 2006 Jan 19 | Giessen | MVK | Cat | Urine | B1 | ND | ND | 12 |

| 437¶ | baum. | 2006 Jan 31 | Giessen | CVK | Cat | Ear | C1 | 13 | II | 9 |

| 462¶ | baum. | 2006 Feb 1 | Giessen | MVK | NR | Exam table | C1 | 13 | II | 3 |

| P698 | baum. | 2006 Feb 4 | Hofheim | Private | Cat | Urine | C1 | ND | ND | 3 |

| 580¶ | NC | 2006 Feb 9 | Giessen | CVK | Dog | Nose | NT | 4 | – | 16 |

| 1231a¶ | baum. | 2006 Mar 24 | Giessen | MVK | Cat | Urine | A2 | 8 | I | 3 |

| 1316¶ | baum. | 2006 Apr 3 | Giessen | CVK | Cat | Urine | C1 | 13 | II | 3 |

| P869¶ | baum. | 2008 Feb 1 | Nauen | Private | Horse | Cervix | B1 | 7 | III | 2 |

| 760¶ | baum. | 2008 Feb 2 | Giessen | MVK | Dog | Blood | C6 | 13 | II | 9 |

| 1173¶ | baum. | 2008 Feb 13 | Giessen | CVK | Dog | Wound | Un | 16 | II | 3 |

| 1227¶ | baum. | 2008 Feb 18 | Giessen | AGVK | Dog | Vagina | Un | 9 | NA | 19 |

| 1356 | baum. | 2008 Feb 21 | Giessen | CVK | Dog | Fistula | B1 | ND | ND | 6 |

| P2134–1¶ | gen. sp.3 | 2008 Mar 20 | Solingen | Private | Bird | Pharynx | NT | 2 | ND | 22 |

| P2347¶ | gen. sp.3 | 2008 Mar 29 | Dortmund | Private | Guinea pig | Lips | Un | 3 | ND | 18 |

| 1936¶ | baum. | 2008 Mar 29 | Giessen | MVK | Dog | CVC | C1 | 15 | II | 3 |

| 2006 | baum. | 2008 Apr 3 | Giessen | MVK | Dog | CVC | C1 | ND | ND | 3 |

| 3061¶ | baum. | 2006 Jun 12 | Giessen | AGVK | Cow | Udder | Un | 17 | NA | 21 |

| 4199¶ | baum. | 2008 Aug 15 | Giessen | CVK | Dog | Vagina | Un | 5 | NA | 16 |

*PFGE, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis; AFLP, amplified fragment-length polymorphism; baum., baumannii; MVK, medical department, small animal clinic of the Justus-Liebig-University Giessen; ND, not done; CVK, surgical department, small animal clinic of the Justus-Liebig-University Giessen; NT, nontypeable; NA, not affiliated with either of the European clones I–III; AGVK, gynecologic and andrologic department of the Justus-Liebig-University Giessen; gen. sp., genomic species; NR, not relevant; NC, not classified; CVC, central venous catheter; Un, unique PFGE strain (strain does not belong to either PFGE cluster A, B, or C, indicating a low degree of genetic related). †Taxonomic designation according to ARDRA results, AFLP being complementary. Species, Acinetobacter species. ‡European clones as described (5,6) and delineated by AFLP at ≈80% similarity cutoff level (4). §Profile as given in Table. ¶Isolates tested by AFLP.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Zordan S, Prenger-Berninghoff E, Weiss R, van der Reijden T, van den Broek P, Baljer G, et al. Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in veterinary clinics, Germany. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2011 Sep [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1709.101931

References

- 1.Dijkshoorn L, Nemec A, Seifert H. An increasing threat in hospitals: multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:939–51. 10.1038/nrmicro1789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peleg AY, Seifert H, Paterson DL. Acinetobacter baumannii: emergence of a successful pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21:538–82. 10.1128/CMR.00058-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maragakis LL, Perl TM. Acinetobacter baumannii: epidemiology, antimicrobial resistance, and treatment options. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1254–63. 10.1086/529198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nemec A, Dijkshoorn L, van der Reijden TJ. Long-term predominance of two pan-European clones among multi-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii strains in the Czech Republic. J Med Microbiol. 2004;53:147–53. 10.1099/jmm.0.05445-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dijkshoorn L, Aucken H, Gerner-Smidt P, Janssen P, Kaufmann ME, Garaizar J, et al. Comparison of outbreak and nonoutbreak Acinetobacter baumannii strains by genotypic and phenotypic methods. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1519–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Dessel H, Dijkshoorn L, van der Reijden T, Bakker N, Paauw A, van den Broek P, et al. Identification of a new geographically widespread multiresistant Acinetobacter baumannii clone from European hospitals. Res Microbiol. 2004;155:105–12. 10.1016/j.resmic.2003.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abbott Y, O’Mahony R, Leonard N, Quinn PJ, van der Reijden T, Dijkshoorn L, et al. Characterization of a 2.6 kbp variable region within a class 1 integron found in an Acinetobacter baumannii strain isolated from a horse. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;55:367–70. 10.1093/jac/dkh543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Francey T, Gaschen F, Nicolet J, Burnens AP. The role of Acinetobacter baumannii as a nosocomial pathogen for dogs and cats in an intensive care unit. J Vet Intern Med. 2000;14:177–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk and dilution susceptibility tests for bacteria isolated from animals, approved standard, 2nd ed. M31–A2. Wayne (PA): The Committee; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dijkshoorn L, Van Harsselaar B, Tjernberg I, Bouvet PJ, Vaneechoutte M. Evaluation of amplified ribosomal DNA restriction analysis for identification of Acinetobacter genomic species. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1998;21:33–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nemec A, Krizova L, Maixnerova M, Tanny der Reijden JK, Deschaght P, Passet V, et al. Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus–Acinetobacter baumannii complex with the proposal of Acinetobacter pittii sp. nov. (formerly Acinetobacter genomic species 3) and Acinetobacter nosocomialis sp. nov. (formerly Acinetobacter genomic species 13TU). Res Microbiol. 2011;162:393–404. 10.1016/j.resmic.2011.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van den Broek PJ, van der Reijden TJ, van Strijen E, Helmig-Schurter AV, Bernards AT, Dijkshoorn L. Endemic and epidemic acinetobacter species in a university hospital: an 8-year survey. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:3593–9. 10.1128/JCM.00967-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dijkshoorn L. Typing Acinetobacter strains: applications and methods. In: Bergogne-Berezin E, Friedmann H, Bendinelli M, editors. Acinetobacter biology and pathogenesis. New York (NY): Springer Science+Business Media; 2008. p. 85–104. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seifert H, Dolzani L, Bressan R, van der Reijden T, van Strijen B, Stefanik D, et al. Standardization and interlaboratory reproducibility assessment of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis-generated fingerprints of Acinetobacter baumannii. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:4328–35. 10.1128/JCM.43.9.4328-4335.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van den Broek PJ, Arends J, Bernards AT, De Brauwer E, Mascini EM, van der Reijden TJ, et al. Epidemiology of multiple Acinetobacter outbreaks in the Netherlands during the period 1999–2001. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12:837–43. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01510.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]