Abstract

Trps1 has been proposed as a candidate gene for a mouse bone mineral density (BMD) QTL on Chromosome (Chr) 15, but it remained unclear if this gene was associated with BMD in humans. We used newly available data and advanced bioinformatics techniques to confirm that Trps1 is the most likely candidate gene for the mouse QTL. In short, by combining the raw genetic mapping data from two F2 generation crosses of inbred strains of mice, we narrowed the 95% confidence interval of this QTL down to the Chr 15 region spanning from 6 to 24 cM. This region contains 131 annotated genes. Using block haplotyping, all other genes except Trps1 were eliminated as candidates for this QTL. We then examined associations of 208 SNPs within 10kb of TRPS1 with BMD and hip geometry, using human genome-wide association study (GWAS) data from the GEFOS consortium. After correction for multiple testing, six TRPS1 SNPs were significantly associated with femoral neck BMD (P=0.0015–0.0019; adjusted P=0.038–0.048). We also found that three SNPs were highly associated with femoral neck width in women (rs10505257, P = 8.6x10−5, adjusted P=2.15x10−3; rs7002384, P = 5.5x10−4, adjusted P=01.38x10−2). In conclusion, we demonstrated that combining association studies in humans with murine models provides an efficient strategy to identify new candidate genes for bone phenotypes.

Keywords: Trichorhinophalangeal syndrome I, mouse models, human genetic association study, bone mineral density

1.0 Introduction

As osteoporosis incidence is predicted to increase as the American population ages [1], much effort has focused on finding the genetic mechanisms underlying this disease. It is well established that bone mass, measured by bone mineral density (BMD), is highly heritable [2]. As BMD measures alone are insufficient to predict future fracture in many patients, much effort has focused on identifying other clinically measurable phenotypes that either alone or in concert with BMD can be used to better predict fracture risk, such as long bone geometry. Measures of bone geometry can be used to predict risk of osteoporotic fractures [3–6] and these phenotypes are also heritable [7–9]. Therefore, identification of genes that regulate BMD and bone geometry will enhance our understanding of osteoporosis etiology. The assumption has been that finding the genetic causes of this disease would lead to better fracture risk prediction and new and better treatment options.

Genome wide association study (GWAS) methodologies have been used successfully to identify a small number of loci underlying BMD but very little of the variance in this phenotype has been accounted for in the largest GWAS for BMD published to date [10]. A major problem with genome-wide studies is control of Type I Error due to a large number of multiple tests. For example, at 0.1% significance level, the analysis of association between 2.5 million single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and a single phenotype would be expected to generate up to 2,500 false positive results under the null hypothesis of no association. To correct for multiple testing, most studies use a critical significance value of α = 5x10−8. The concern is that true associations are discarded by using such a stringent significance cut off and that these discarded, but otherwise true associations, could account for some of the missing variance. It has been suggested that incorporating prior knowledge, such as findings from previous linkage and association studies can be used to counteract such a harsh multiple-testing penalty [11]. The addition of cross-species comparisons provides an opportunity to examine additional candidates that would otherwise fall short of the stringent statistical level for genome-wide significance. The high degree of concordance between genetic loci mapped in humans with those mapped in mice and the large number of substantiated loci for BMD that have been mapped in the mouse, make the mouse an ideal species for this type of cross-species comparison.

In our previous study, we identified a quantitative trait locus (QTL) on proximal mouse Chromosome (Chr) 15, with a peak location of 21.96 cM [12, 13] and trichorhinophalangeal syndrome I (Trps1) was tentatively identified as a candidate gene for this QTL. In this study, we confirmed that Trps1 is indeed a candidate gene for this mouse QTL using improved bioinformatics methods. We then demonstrated an association between single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) in TRPS1 and osteoporosis-related traits in large samples of human subjects.

2.0 Materials and Methods

2.1 Combined Cross Analysis

The raw mapping data were available for two crosses in which a BMD QTL with a peak location on proximal mouse Chr 15 were mapped: C57BL/6J (B6) x C3H/HeJ (C3H) [14] and NZB/B1NJ (NZB) x SM/J (SM) [13]. These data sets can be downloaded in their entirety from: www.QTLarchive.org. Other mouse crosses have mapped QTL to proximal Chr 15 for BMD [12], however, the raw data from these crosses were not available to us for use in this analysis. The NZBxSM data sets, as originally published, contained data from both males and females, but only data from females was available for B6xC3H. For consistency, only the female data were used for the combined cross analysis. Combined cross analysis was done using the biallelic method proposed by Li and colleagues [15]. In brief, the data for only Chr 15 was extracted from each dataset. The high and low allele for BMD for this QTL on Chr 15 was determined for each cross. Then, the low allele was re-coded to a common designation of “A” and the high allele re-coded as “B” for the genotyping data for each data set. A variable of “Cross” (i.e. to indicate which cross the data came from) was created for each mouse. The datasets were then combined and a single-QTL model scan was performed to identify QTLs on Chr 15 using “Cross” as both an additive and as an interactive covariate in the model. The data were permuted 1,000 times to determine significance thresholds for both the additive and interactive models [16]. The widely accepted logarithm of odds (LOD) score cutoffs of p < 0.63 for suggestive QTL and p < 0.05 for highly significant QTL were used in this study [17]. QTLs for which the LODs exceeded the highly-significant thresholds for both models were considered true QTLs. The Bayes credible interval function in R/qtl (bayesint) was used to approximate the 95% confidence intervals for the QTL peak location for both the additive and the interactive model. The additive and interactive models were then compared to assess cross specificity of the QTL. All QTL analyses were done using the R/qtl software package [18] (R version 2.10.1, qtl library version 1.14–2, http://www.rqtl.org/).

2.2 Haplotyping and SNP sequencing

Block haploytyping to narrow the mouse QTL was conducted as described previously [19]. Single Nucleotide Polymorphism genotypes for B6, NZB, SM, and C3H were obtained from the “Broad2” genotyping set, which can be freely downloaded at: http://phenome.jax.org/. This data set was chosen as it was the only dense SNP set containing allele data for all of the inbred strains of interest. The upper and lower boundaries of the Bayes credible interval for the QTL peak identified in the additive model of the combined cross analysis were converted to megabase (Mb) position (http://cgd.jax.org/mousemapconverter) and all SNP genotypes falling in this interval were retrieved. The alleles for each SNP were examined and SNPs for which the pattern of alleles for each of the inbred strains met the following conditions were identified:

| (1) |

The SNPs meeting the allele distribution pattern defined in equation (1) were then examined to determine if they fell within a known or predicted gene, or adjacent to a known or predicted gene. Genes containing two or more SNPs that met the allele distribution pattern of equation (1) were considered preliminary candidate genes for the QTL.

As adding additional strains to the haplotype analysis could further filter this list of preliminary candidate genes, we searched the literature to determine if other QTL for BMD had been identified with a peak at or near to the peak location of the QTL identified above in the combined cross analysis. An MRLxCAST BMD QTL, with a peak location of 22.92 cM, has been reported in the literature [12, 20]. The MRL strain contributed the high allele for this QTL. As the CAST strain is a wild derived inbred strain, and the use of wild derived strains in haplotype analysis can confound the results, the inclusion of the MRL and the CAST alleles in the haplotype analysis was done in two steps. First, SNPs for which the allele met the following conditions where identified:

| (2) |

In the second step, the CAST alleles were added as follows:

| (3) |

Genes containing SNPs that met allele distribution patterns (2) and (3) were recorded. To further refine the short-list of genes, we focused on the SNPs with alleles different between MRL and the CAST:

| (4) |

After haplotyping, we were left with a single candidate gene, Trps1 and a non-synonymous SNP has been reported in this gene, rs32398060. True, direct measure, genotyping was not available for this for NZB and MRL. This gene was sequenced using standard Sanger sequencing techniques, as previously described [21]. The MRL and NZB sequences for this region of the Trps1 gene have been submitted to GenBank and can be retrieved using the following accession numbers: (accession numbers pending).

2.3 GWAS meta-analysis

The Genetic Factors for Osteoporosis (GEFOS) consortium was organized to perform meta-analyses of the osteoporosis-related phenotypes. Details on the participating cohorts, samples, DNA extraction techniques, genetic markers and genotyping assays, and statistical analyses, are provided elsewhere ([10] and [22]). We combined the results from five cohorts of Caucasian ancestry (Framingham, Rotterdam, deCODE, ERF, and TwinsUK) for femoral neck (FN) and lumbar spine (LS) BMD [10] and from three cohorts (Framingham, Rotterdam, and TwinsUK) for hip geometry [22]. We performed a meta-analysis of 19,195 adult subjects for FN and LS BMD. In this analysis, data from males and females were combined [10]. For hip geometry traits, we analyzed data from 11,290 adult subjects. In this analysis, data from men and women were analyzed both separately as well as in a sex-combined fashion [22]. Hip geometric indices included femoral neck-shaft angle (NSA), femoral neck length (FNL), and narrow-neck width (NNW) [12].

Since the participating studies performed whole-genome genotyping using different platforms (Affymetrix and Illumina platforms), the software package MACH [23, 24] was used to impute autosomal SNPs from the HapMap project. Instead of using the “best guess” genotype for each individual, the additive dosage of the allele from 0 to 2 (which is a weighted sum of the genotypes multiplied by their estimated probability), was used to perform association tests to account for the uncertainty of imputation. The ratio of the empirically observed dosage variance (from the imputed genotypes) to the expected (under the binomial distribution) dosage variance (computed from the estimated minor allele frequency) was calculated for every SNP as a quality score for imputation. SNPs with the variance ratio < 0.3 were excluded.

Weighted z score-based or inverse-variance meta-analysis approaches (assuming fixed effects) were applied to estimate combined p-values using the METAL program [25]. In brief, all association results were expressed relative to the forward strand of the reference genome based on HapMap (dbSNP126). For the weighted z score-based approach, the two-sided p-value was converted to a z-statistic that was signed to reflect the direction of the association given the reference allele. Statistics were summed across studies; each z-score was weighted; the squared weights were chosen to sum to 1 and each sample-specific weight was proportional to the square root of the effective sample size in each study cohort. We calculated the effective sample size as the variance ratio multiplied by number of individuals in the analyses.

We analyzed 208 SNPs in and around the TRPS1 gene. All SNPs were located within the genomic interval consisting of 10 Kb up and 10 Kb downstream of the TRPS1 coding region (genetic positions from 116,420,724 to 116,681,228 according to NCBI build 37.2). With SNP imputation based on HapMap Phase II (Release 21) European American (CEU) population, these 208 SNPs captured up to 100% (r2 threshold of 0.8) of the total number of SNPs in this gene, with an average inter-marker distance of 1,304 bp. The SNP for two additional negative control genes were also examined, CDH10 and CSMD3. Both of these genes are located within the confidence interval for our mouse BMD QTL, however, the haplotype analyses strongly suggested that these genes could not be the causative gene. Specifically, for the CDH10 gene, which is comparable in size to TRPS1, we examined 206 SNP and for the CSMD3 gene, which is much large than TRPS1, we examined 1071 SNP. We extracted the aggregate results for these SNPs from both FN and LS BMD meta-analysis [10], as well as the hip geometry meta-analysis [22]). Regional plots were created utilizing the SNAP tool (http://www.broadinstitute.org/mpg/snap/index.php).

2.4 Adjustment for multiple testing

To correct for multiple testing [26], we applied a Bonferroni correction on an estimated effective number of independent tests. Using principal components analysis (PCA) of the correlation matrices of SNPs in/near TRPS1 [27], we obtained a total number of 25 independent principal components that were enough to account for ≥90% of variation of SNPs. Thus, for a nominal α=0.05 and approximately 25 independent tests, we determined the adjusted critical value to be α (adjusted) = 0.05/25 ~0.002 and calculated the Bonferroni corrected P-value (adj-P) as the observed P-value times the effect number of independent tests. In linkage disequilibrium (LD) analyses we found that nearly 150 out of the total 208 SNPs were redundant with pair-wise r2>0.95 with one or more SNP. Thus, not surprisingly, our estimated number of total independent tests is 25. In a similar fashion, 30 independent principal components were identified for CDH10 and 76 principal components were identified for CSMD3, which accounted for 90% of the variation for both genes.

3.0 Results

3.1 Combined cross analysis

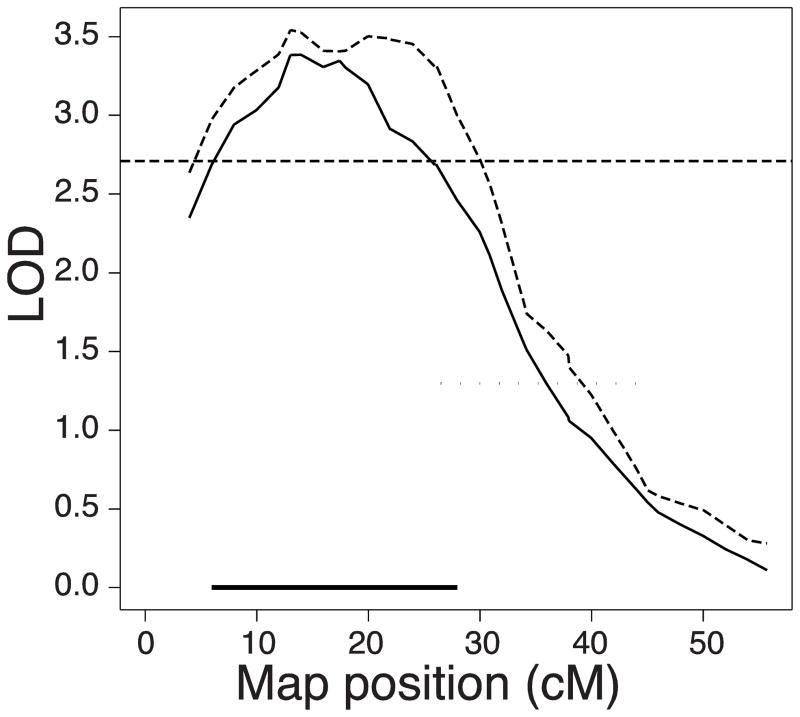

BMD QTL have been reported on Chr 15 in two crosses: a vertebral volumetric BMD QTL mapped in B6xC3H with a peak location at 13 cM (peak LOD score = 2.65) and a vertebral areal BMD QTL mapped in NZBxSM with a peak location of 22 cM (peak LOD score = 2.24). Both of these QTL exceed the statistically suggestive threshold (P <0.63), but not the statistically significant threshold (P<0.05) [17]. The B6 allele was the “high BMD” allele for the B6xC3H and NZB was the “high BMD” allele in the NZBxSM cross [12]. The confidence intervals of these QTL are quite broad. Therefore, we merged the raw mapping data for these two crosses using the biallelic method as described above to narrow the confidence interval and thus narrow the list of putative candidate genes. Using the additive model, a single QTL was mapped to Chr 15 upon combining the data from the two crosses, with a peak location of 13.0 cM and a peak LOD score of 3.79 (Figure 1). After 1000 permutations of the data, the statistically significant LOD threshold was determined to be 1.93 for the additive model, thus the QTL mapped in the combined data set is considered to be highly significant. No difference was noted for the peak LOD score for the additive model versus the interactive model (with “Cross” as an interactive covariate in the model; Figure 1), thus it was concluded that this QTL was shared between the two crosses. The 95% confidence interval for this QTL extended from 5.96 to 26.07 cM (12.7 to 61.7 Mb) on mouse Chr 15, which is a considerably smaller region of interest than the confidence intervals for the original QTLs which extended from 3.96 to 47.41 cM [12]. The refined QTL interval contains 144 annotated genes.

Figure 1. Chromosome 15 LOD score plots for the combined cross analysis.

The LOD plot results for the additive model are represented by the solid black line and the interactive model by the dashed line. The Bayes credible interval is represented by the horizontal thick black bar. The highly significant and the suggestive LOD thresholds are indicated by the horizontal dashed and dotted lines respectively.

3.2 Identification of Trps1 as a candidate gene utilizing the haplotype analysis

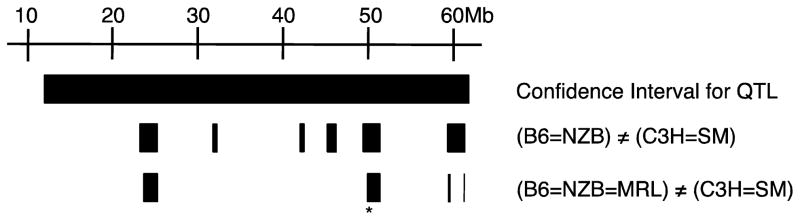

Allele information was available in the “Broad II 90 Strains” SNP dataset for 3061 SNPs within the 95% confidence interval for the refined Chr 15 QTL, as calculated from the combined cross analysis. Six groupings of SNPs, or haplotype blocks, were identified wherein B6 and NZB shared the same allele, C3H and SM shared an allele, but these two groups differed from each other (Figure 2). Five genes fell into these six haplotype blocks, including: Cdh18, Oxr1, Trps1, Eif3s3 and E430025E21Rik. A BMD QTL mapped in an MRL/MpJ (MRL) by CAST/EiJ (CAST) cross (peak location of 22.9 cM) has been reported [12, 20]. The MRL strain, which corresponds to the “high” allele for this QTL, was added to the haplotype analysis such that alleles for MRL must be the same as those for B6 and NZB (Equation 2). Three haplotype blocks were found that met these conditions (Figure 2), with only the distal two blocks containing the coding regions for any known genes. Lastly, the alleles for the CAST strain were added to this analysis (Equation 3). Only one SNP in the genetic region surrounding the E430025E21Rik gene met the haplotyping criteria after the addition of the CAST strain. By operational definition a haplotype must consist of more than one SNP, suggesting that the E430025E21Rik gene was not the candidate for this QTL. In contrast four SNPs in and around the Trps1 gene met our haplotyping criteria, thus supporting the hypothesis that Trps1 was the underlying candidate gene. Two non-synonomous SNP have been reported in Trps1: rs32398060, which results in a predicted valine to leucine substitution and rs50580568 which results in a putative aspartate to glycine substitution. Direct measure allele information was avaliable for all strains of interest in this study for rs32398060 except MRL and NZB. Therefore, we sequenced this SNP in these two strains. We determined that the MRL and CAST strains share an allele for this SNP, suggesting that this could not be the causitive polymorphism for this QTL. Furthermore, B6, C3H, NZB and SM all shared the same allele for rs50580568, suggesting that this polymorpism was also not causative (http://phenome.jax.org, accessed Dec 1, 2011).

Figure 2. Narrowing of the Chromosome 15 QTL using block haplotyping.

The 95% confidence interval (Bayes credible interval) for the combine QTL extended from 12.7 to 61.7 Mb as is represented by the solid black bar. Using allele information from B6, SM, NZB and C3H much of this interval was eliminated as a possible location for the candidate gene, resulting six haplotype blocks (represented by small black boxes) wherein the candidate gene could be located. By adding in allele information for MRL, the number of haplotype blocks was reduced. The Trps1 gene (location indicated by an *) was determined to be the most likely candidate gene based on the SNP evidence.

3.3 Association tests between the SNPs and bone phenotypes in human samples

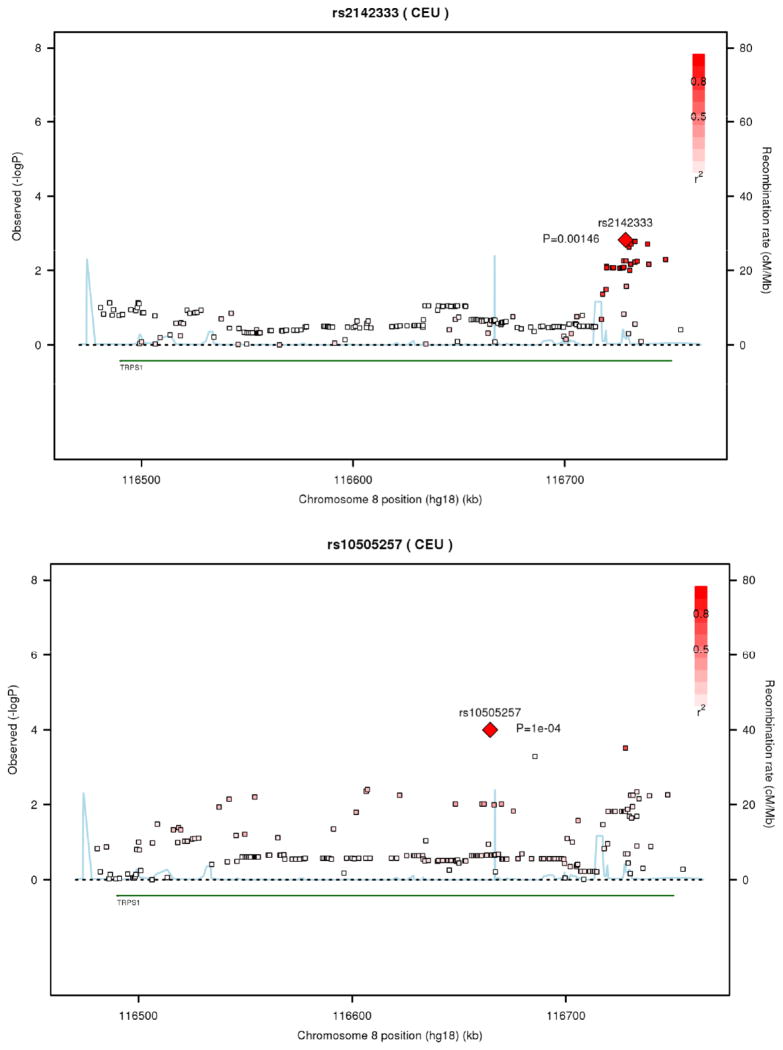

We extracted the results for 208 Affymetrix SNPs in and around TRPS1 for FN and LS BMD as well as for hip geometry from the meta-analysis of the GEFOS consortium data. For DXA-derived BMD, the sex-combined meta-analysis results were the only results available. Of the 208 SNPs examined in the TRPS1 gene, 6 SNPs were associated with FN BMD at p < 0.0019 (adjusted P=0.0475, Table 2 Part a), which corresponds to a nominal significance p-value adjusted for 25 independent tests. These SNPs were intronic, with minor allele frequency (MAF) = 0.32 and there was high LD (r2 0.96–1.0) among them. No nominally-significant (i.e. p < 0.05) associations with LS BMD were observed. Regional plots are provided in Figure 3a and 3b. No association was found between LS BMD or FN BMD for any of the SNP in the CDH10 or CSMD3 genes (data not shown). This lack of association for these two genes is important as it demonstrates that using the mouse to identify test genes for examination in human data sets is appropriate and effective.

Table 2.

Genome-wide Association results (GEFOS meta-analyses) in the TRPS1 region

| Trait | SNP | Position (Build 37.2, HG18) | Alleles | Minor Allele frequency | Effect | Standard Error | P Value | P Value (adjusted)** | Direction | Location in TRP S1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a. FN (both sexes) | ||||||||||

| rs2142333 | 116,728,632 | t/c | 0.322 | 0.0383 | 0.012 | 0.001459 | 0.07295 | ++++−++−+ | intron | |

| rs2178951* | 116,728,708 | a/g | 0.677 | −0.0382 | 0.012 | 0.001509 | 0.07545 | −−−−+−−+− | intron | |

| rs2737247* | 116,729,539 | a/g | 0.677 | −0.0382 | 0.012 | 0.001501 | 0.07505 | −−−−+−−+− | intron | |

| rs2721965* | 116,731,212 | a/c | 0.680 | −0.0371 | 0.012 | 0.001891 | 0.09455 | −−−−−+−+− | intron | |

| rs2737253* | 116,733,096 | a/g | 0.320 | 0.0377 | 0.0119 | 0.001614 | 0.0807 | +++++−+−+ | intron | |

| rs179442* | 116,738,943 | t/c | 0.320 | 0.0371 | 0.012 | 0.001904 | 0.0952 | +++++−+−+ | intron | |

| b. NNW (women) | ||||||||||

| rs10505257 | 116,664,483 | a/g | 0.187 | −0.0348 | 0.0089 | 8.6E-05 | 0.0043 | +−? | intron | |

| rs7002384† | 116,685,371 | a/g | 0.013 | −0.1613 | 0.0467 | 0.000549 | 0.02745 | −−? | Missense: pos. 667 (Ser⇒Leu) | |

| rs11780385 | 116,727,736 | a/g | 0.192 | −0.0319 | 0.0089 | 0.000336 | 0.0168 | +−? | intron | |

| c. (men) | ||||||||||

| FNL | rs6982767 | 116,996,878 | a/g | 0.056 | 0.1653 | 0.0496 | 0.00085 | 0.0425 | ++ | intergenic |

| FNL | rs6986858 | 116,997,237 | t/c | 0.056 | 0.1654 | 0.0496 | 0.000847 | 0.04235 | ++ | intergenic |

| FNL | rs4598283 | 116,998,278 | t/c | 0.056 | −0.1655 | 0.0496 | 0.000842 | 0.042 | −− | intergenic |

| FNL | rs7817477 | 117,002,822 | a/g | 0.056 | −0.1645 | 0.0495 | 0.000899 | 10.04495 | −− | intergenic |

| NNW | rs2223065 | 117,091,502 | t/g | 0.018 | 0.2778 | 0.0748 | 0.000205 | 0.01025 | ++ | intergenic |

MAF = minor allele frequency; FN – Femoral neck BMD, FNL - femoral neck length; NNW - narrow-neck width.

LD r2 = 0.034 with the above SNP; LD r2 = 0.034 with the above SNP and r2 = 0.712 with rs10505257

LD r2 ~1 with the above SNP

adjusted for multiple correlated phenotypes and SNPs in LD

Figure 3. Regional plots for SNP-phenotype association (index SNPs are marked).

(a) FN BMD, men and women (rs2142333); (b) Neck Width, female sample (rs1526463). The Blue line refers to the genome-wide recombination rate from Phase 2 International HapMap Project estimated from phased haplotypes in HapMap Release 22 (NCBI 36). These rates have been estimated from the CEU population. The observed log p-values for all assayed SNP are indicated by open squares, with the peak or most associated SNP indicated by a diamond. The r2 values for each SNP are indicated by increasing intensity of red colour. We observed that there is strong association of SNPs in the distal portion of the TRPS1 gene with BMD.

For hip geometry (three traits), results were available from a meta-analysis of three cohorts: two consisting of males and females and one female-only cohort. The best association signal was with NNW in women, with intronic SNPs rs10505257 (MAF ~0.19, P=8.6x10−5, adjusted P=2.15x10−3) and rs11780385 (MAF~0.19, p=3.0x10−4, adjusted P=7.5x10−3; Table 2, Part b). These SNPs were in moderately high LD (r2 = 0.712). A rare non-synonymous coding variant rs7002384 (MAF = 1%), was also associated with NNW in women (p=5.5x10−4, adjusted P=1.38x10−2); notably, this SNP was not in LD with either rs10505257 or rs11780385 (r2 ~0.03). The regional plot is provided in Figure 3b. In sexes-combined analysis, these SNPs were nominally-significantly associated with NNW. In men, rs2205256 was associated with FNL at p<6.8x10−3 (adjusted P=0.17, Table 2c). There were no nominally-significant associations with NSA in either sex.

4.0 Discussion

Despite the number of mouse crosses generated in which replicable QTL for BMD were mapped, very few of the underlying genes have been identified [12]. Similarly, very little of the variance in BMD has been explained using GWAS [10]. In this study of osteoporosis-related phenotypes, we demonstrated that combining a genome-wide search in murine models with association studies in human populations provides an efficient strategy to identify new candidate genes for bone phenotypes. This combined approach is superior to previous attempts to identify candidate genes for a number of reasons. First, for mouse-based mapping studies, a number of techniques have been developed to narrow QTL [19]; these tools have been underutilized for the study of bone QTL. Second, we have new and better resources for mapping and narrowing QTL than were available when many of the crosses used for identification of BMD QTL were made. These new resources include a new, more accurate, genetic map for the mouse [28] and new and better SNP databases. Third, as we used the mouse to narrow the region of interest to be tested in the human cohort, we were able to limit the number of tests being examined, and thus reduce the multiple testing penalty. Each of these combined-strategy elements are discussed further below.

Haplotyping is a bioinformatics tool that can be used to select candidate genes for a QTL. The common laboratory strains of mice, created in the first half of the 20th century, arose from small founder populations and contain regions of DNA that are identical by descent. These regions can be inferred by stretches of identical alleles. When hunting for the gene responsible for a QTL found in multiple crosses, it is assumed that regions of the genome that are genetically identical between the two parents of a given cross cannot contain the gene(s) responsible for a QTL detected in that cross [29]; instead, the gene(s) must reside in a region where the two strains are genetically different. When several different crosses detect the QTL that map to the same genomic location, haplotype analysis can be used to reduce the size of the QTL region by up to 90% [29], however, the assuption must be made that the same candidate gene(s) underlies all co-mapping QTL. Databases containing SNPs genotyped for inbred strains of mice are used for this type of analysis. In order for this method to be effectively employed, a very dense SNP data set is needed. Otherwise, one risks missing the correct gene. Haplotyping was used to originally identify Trps1 as a candidate for this QTL on mouse Chr 15 [12, 13]. Since that work was completed, newer and much denser sets of SNP data for mouse inbred strains have been generated and there was concern that the correct gene underlying this QTL could have been inadvertently missed. Thus, before testing this gene in human populations, we revisited our haplotype analysis with updated information.

A new mouse genetic map has recently become available for use in QTL analysis. This new map was generated for the purpose of correcting errors that had existed with regards to marker order and/or marker spacing in the older genetic map, as well as to make a genetic map that was better correlated to the physical map of the mouse genome [28]. This new genetic map was used in this study. Recently, we undertook the task of remapping BMD related QTL using this new genetic map [12]. As was expected, we found in our remapping study that the peak location of some QTL was shifted relative to one another. As a result, QTL once thought to be concurrent, were actually found to be independent of one another. When the original haplotype analysis for the Chr 15 QTL was published [13], it was assumed that the B6xDBA, B6xC3H and NZBxSM QTL that mapped to proximal Chr 15 were all one QTL. This assumption was based on the literature reported peak locations. When these QTL were remapped using the new genetic map [12], it became apparent that the B6xDBA QTL was actually significantly proximal to the other two QTL and it was not longer valid to use the DBA alleles in the haplotype analysis. A suggestive QTL for whole body areal BMD is reported in the literature, as mapped in an MRLxSJL cross, with a peak marker of D15Mit179 [30]. When we conducted our QTL remapping effort using the updated genetic map, this QTL was not found [12]. There are many explanations for this, including the use of different analytic methods when comparing our study to the originally published study, and fundamental differences in marker order and spacing between the new genetic map used in our analysis and the genetic map available when that data was originally analyzed. Because of the discrepancies between our analysis of the MRLxSJL data and the previously published results, we decided not to include the MRLxSJL QTL information in the haplotype analysis conducted for this study. In sum, because of the newly available SNP databases, our better mapping results for the BMD QTL in the mouse, reanalyzing the bioinformatics results for this QTL was warranted. However, we recognize that complete resequencing of the genomes for MRL/MpJ, NZB/B1NJ and SM/J has not yet been completed. This leaves open the possibility that we still could have missed a causative gene for this QTL in mice as we do not have complete SNP information for these three strains. This is a limitation of this study, one that applies to all haplotype analysis of QTL using strains of mice that have not yet been resequenced. Still, our goal was to direct the analysis of the human association data using the results from our mouse studies, not to replace analysis of the human data, and so this limitation did not preclude the use of haplotype analysis in this study.

We included data for an MRLxCAST QTL [20] in the haplotype analysis reported herein. This QTL had not yet been published when our original examination of the proximal Chr 15 QTL was conducted. The CAST/EiJ (CAST) strain is considered a wild derived strain of a different sub-species than the majority of our common laboratory strains and is thus very unique genetically [31]. For this reason, the raw data for the MRLxCAST F2 cross data were not used in the combined cross analysis; instead the MRL and CAST strains were added to the haplotyping separately. When the MRL strain was added to the analysis, the QTL was narrowed to two candidate genes, Trps1 and Eif3h, but with the addition of the CAST strain, Eif3h was eliminated. Because of the concerns raised by forcing the CAST alleles to be the same as the C3H and the SM alleles, we examined all of the reported SNP in Eif3h separately. Two SNPs existed in the Eif3h gene in the Broad II HapMap data set wherein MRL alleles were different than the CAST alleles, which is a condition that must be true for this QTL, but there were no SNP in Eif3h wherein the allele satisfied the following conditions: (B6=NZB=MRL) ≠ CAST. As MRL, B6 and NZB are all traditional laboratory derived strains, assuming that B6 must equal NZB, which must equal MRL is reasonable for the haplotyping. As SNPs were found in Trps1 that met even the more stringent haplotyping criteria described above, this gene was considered to be the most likely candidate for this QTL. We therefore proceeded to seek evidence of association of this gene with osteoporosis-related traits in humans.

A major problem of GWAS is control of Type I Error due to a multiple testing. This is an inherent nature of the hypothesis-free (“agnostic”) approach of whole-genome screening. However, by incorporating prior knowledge, a less stringent statistical level for genome-wide significance can be used. We used data from the mouse to narrow the region of interest to be tested in the human cohort, which allowed us to limit the number of tests being examined, and thus reducing the multiple testing penalty. After applying Bonferroni correction on the effective number of independent tests to determine the significance level of association signals, [27]; we found that six intronic SNPs were associated with femoral neck BMD at p ~ 0.0015. These associations endured adjustment for multiple testing.

For hip geometry, the phenotype with the most significant association with genetic variation in the TRPS1 gene was narrow-neck outer diameter (narrow neck width). Specifically, 3 SNPs were significantly associated with this phenotype in women: 2 SNPs (rs10505257 and rs11780385), which were in moderately high LD (best p-value 8.6x10−5, adjusted P=2.15x10−3), as well as a rare non-synonymous coding variant rs7002384 (MAF = 1%, p-value < 5.5x10−4, adjusted P=1.38x10−2). One SNP was also associated with femoral neck length in a relatively modest-size sample of men. In a previous preliminary study, we genotyped SNPs within, immediately proximal and immediately distal to the TRPS1 gene in a subsample of the Framingham Osteoporosis Study (Ackert-Bicknell, unpublished). We found that one SNP, rs720928 (MAF = 0.22), was associated with broadband ultrasound attenuation of the heel bone, in a combined-sexes sample, with p=0.00036. This variant is in linkage disequilibrium with the SNPs associated with FN BMD (r2 0.38–0.40) in this study, therefore, these markers probably point to the same signal. We therefore assume that TRPS1 manifests associations with human osteoporosis-related femoral phenotypes.

The TRPS1 protein is a transcription factor that contains nine zinc-finger DNA binding motifs and is thought to act as a transcriptional repressor. Specifically, this transcription factor forms a homodimer, that is able to bind to tandem (T/A)GATA(A/G) or inverse GATA consensus sequences [32]. Mutations in TRPS1 in humans cause trichorhinophalangeal syndrome, a disease characterized by skeletal and craniofacial malformations and sparse, slow growing hair [33]. Studies have established that TRPS1 enhances chondrocyte proliferation and induces apoptosis in terminally differentiated chondrocytes [34]. Expression of Trps1 has been observed in both early and last stages of osteoblastogenesis and studies have shown that it modulates mineralized bone matrix formation in differentiating osteoblast cells [35]. TRPS1 can repress expression of Runx2, a key regulator of osteoblastogenesis and of chondrocyte maturation [36] and TRPS1 can bind to the osteocalcin (Bglap) promoter and suppress its expression [35, 36]. Mice hemizygous for a deletion of the GATA binding domain of Trps1 have reduced femoral cortical and trabecular bone volume [37]. Together these data suggest that this transcription factor plays an important role in skeletal development and additionally may have a role in maintenance of adult skeletal mass.

Non-synonomous (Cn) SNP in the TRPS1 gene have been identified in both mice and humans. Specifically, in mice, two Cn SNP have been identified: rs32398060 and rs50580568. Based on available data and our own resequencing work, we can conclude that neither of these SNP is the causative allele for mice as the allele distribution for these SNP does not meet our haplotyping requirements. In humans, we have shown alleles for the rs7002384 SNP are associated with narrow-neck outer diameter. However, there is insufficient data available to determine if this SNP is indeed causal or not and further experimentation is therefore required.

In our large sample from human cohorts, there were no nominally-significant (p < 0.05) associations observed with lumbar spine BMD. Indeed, we have previously confirmed skeletal-site specificity of genetic associations with BMD [10]. In the case of TRPS1, this might suggest that this gene is associated with long-bone properties, which are more apparent at the femoral site. In particular, femoral neck length is a function of a balance between chondrocyte proliferation and apoptosis, and osteoblast maturation during growth, which is consistent with the known biological function of TRPS1 [34, 36]. We have also previously shown that there may be sex-specificity of certain genes associated with bone phenotypes [22], however, since no sex-stratified results were available in the GEFOS consortium for BMD, it is not clear whether the signal for FN BMD is driven by association in one gender. The impending round of the BMD GWAS meta-analysis by the GEFOS consortium with larger sample size for each gender, will provide this information.

4.1 Conclusion

We have provided two integrated lines of evidence that support association of the TRPS1 gene with bone phenotypes. From the point of view of mouse genetics, this provides a clinical validation of results obtained from animal models of human disease. From the point of view of human studies, rather than relying totally on statistical association to identify new genes responsible for skeletal phenotypes, we incorporated knowledge independently generated from animal models. This addition of cross-species comparisons produced an additional candidate that would otherwise fall short of the stringent statistical level for genome-wide significance, providing an evidence of benefit of the integrated approach.

Table 1. Characteristics of human samples.

| Framingham | TwinsUK | Rotterdam | ERF * | deCODE | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | Women | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Age (years) | 60.4 (9.4) | 61.3 (9.4) | 49.5 (13.2) | 68.3 (8.2) | 67.3 (7.5) | 49.9 (15.8) | 51.1 (15.7) | 59.5 (14.0) | 65.2 (14.7) |

| BMD (g/cm2 )** | |||||||||

| # Subjects with BMD measurements | 2038 | 1531 | 2734 | 2861 | 2126 | 740 | 488 | 5934 | 809 |

| LS BMD | 1.16 (0.20) | 1.33 (0.21) | 0.99 (0.14) | 1.04 (0.18) | 1.17 (0.20) | 1.12 (0.17) | 1.17 (0.18) | 0.95 (0.17) | 1.03 (0.18) |

| FN BMD | 0.88 (0.14) | 0.98 (0.14) | 0.80 (0.13) | 0.83 (0.13) | 0.92 (0.14) | 0.90 (0.13) | 0.96 (0.15) | 0.70 (0.14) | 0.77 (0.16) |

| Hip Structure | |||||||||

| Analysis (HSA) | |||||||||

| # Subjects with HSA measurements | 1956 | 1465 | 946 | 2478 | 1653 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Femoral Neck Length (NL, cm) | 5.01(0.70) | 5.91 (0.80) | 4.66(0.51) | 5.47 (1.03) | 5.40 (0.97) | ||||

| Femoral Neck Width (NW, cm) | 3.23 (0.43) | 3.73 (0.47) | 2.98 (0.20) | 3.21 (0.32) | 3.20 (0.31) | ||||

| Neck shaft Angle (NSA, degree) | 127.73 (5.47) | 130.02 (5.37) | 131.51 (5.41) | 125.08 (6.57) | 124.76 (6.71) | ||||

ERF – Erasmus Rucphen Family Study (The Netherlands)

Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry: GE-Lunar DPX-L (Framingham and Rotterdam Studies); Hologic QDR 2000W and 4500W densitometer (TwinsUK Study, deCODE), GE-Lunar Prodigy (ERF)

Research Highlights.

Trps1 is a likely candidate gene for a BMD QTL on mouse Chromosome 15.

SNPs in TRPS1 are associated with femoral BMD and hip geometry traits in humans.

Combining genetic studies from humans and mice is advantageous for finding genes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute’s Framingham Heart Study (Contract No. N01-HC-25195), NHLBI 1U01 HL066582, and the following grants from the National Institute on Arthritis Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, and the National Institute on Aging: AR/AG41398 (to DPK), AR053992 (to DK), AR43618 (to WGB) and AG034019 (to CLAB). A portion of this research was conducted using the Linux Cluster for Genetic Analysis (LinGA-II) funded by the Robert Dawson Evans Endowment of the Department of Medicine at Boston University School of Medicine and Boston Medical Center.

We acknowledge generous help of the GEFOS consortium in performing meta-analyses of GWAS of bone-related phenotypes in human participants.

Abbreviations

- TRPS1

Trichorhinophalangeal syndrome I

- BMD

bone mineral density

- GWAS

genome wide association study

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- NNW

narrow neck width

- FNL

femoral neck length

- NSA

femoral neck-shaft angle

- FN

femoral neck

- LS

lumbar spine

- QTL

quantitative trait locus

- Chr

Chromosome

- B6

C57BL/6J

- NZB

NZB/B1NJ

- SM

SM/J

- C3H

C3H/HeJ

- CAST

CAST/EiJ

- MRL

MRL/MpJ

- SJL

SJL/J

- DBA

DBA/2J

- LOD

logarithm of odds

- Mb

megabase

- GEFOS

Genetic Factors for Osteoporosis

- CEU

American trios of European ancestry

- PCA

principal components analysis

- LD

linkage disequilibrium

- MAF

minor allele frequency

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Cheryl L. Ackert-Bicknell, Email: cheryl.ackertb@jax.org.

Serkalem Demissie, Email: demissie@bu.edu.

Shirng-Wern Tsaih, Email: stsaih@mcw.edu.

Wesley G. Beamer, Email: Wesley.Beamer@jax.org.

L. Adrienne Cupples, Email: adrienne@bu.edu.

Beverly J. Paigen, Email: bev.paigen@jax.org.

Yi-Hsiang Hsu, Email: yihsianghsu@hsl.harvard.edu.

Douglas P. Kiel, Email: kiel@hsl.harvard.edu.

David Karasik, Email: karasik@hsl.harvard.edu.

6.0 References

- 1.Report. Bone Health and Osteoporosis: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ralston S, de Crombrugghe B. Genetic regulation of bone mass and susceptibility to osteoporosis. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2492–2506. doi: 10.1101/gad.1449506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faulkner KG, Wacker WK, Barden HS, Simonelli C, Burke PK, Ragi S, Del Rio L. Femur strength index predicts hip fracture independent of bone density and hip axis length. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:593–9. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-0019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gluer CC, Hans D. How to use ultrasound for risk assessment: a need for defining strategies. Osteoporos Int. 1999;9:193–5. doi: 10.1007/s001980050135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marshall D, Johnell O, Wedel H. Meta-analysis of how well measures of bone mineral density predict occurrence of osteoporotic fractures. Bmj. 1996;312:1254–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7041.1254. [see comments] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, Johansson H, Eisman JA, Fujiwara S, Kroger H, Honkanen R, Melton LJ, 3rd, O’Neill T, Reeve J, Silman A, Tenenhouse A. The use of multiple sites for the diagnosis of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:527–34. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-0014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howard GM, Nguyen TV, Harris M, Kelly PJ, Eisman JA. Genetic and environmental contributions to the association between quantitative ultrasound and bone mineral density measurements: a twin study. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13:1318–27. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.8.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ralston SH. Genetic control of susceptibility to osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:2460–6. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.6.8621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karasik D, Shimabuku NA, Zhou Y, Zhang Y, Cupples LA, Kiel DP, Demissie S. A genome wide linkage scan of metacarpal size and geometry in the Framingham Study. Am J Hum Biol. 2008;20:663–70. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rivadeneira F, Styrkarsdottir U, Estrada K, Halldorsson BV, Hsu YH, Richards JB, Zillikens MC, Kavvoura FK, Amin N, Aulchenko YS, Cupples LA, Deloukas P, Demissie S, Grundberg E, Hofman A, Kong A, Karasik D, van Meurs JB, Oostra B, Pastinen T, Pols HA, Sigurdsson G, Soranzo N, Thorleifsson G, Thorsteinsdottir U, Williams FM, Wilson SG, Zhou Y, Ralston SH, van Duijn CM, Spector T, Kiel DP, Stefansson K, Ioannidis JP, Uitterlinden AG. Twenty bone-mineral-density loci identified by large-scale meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1199–206. doi: 10.1038/ng.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roeder K, Bacanu SA, Wasserman L, Devlin B. Using linkage genome scans to improve power of association in genome scans. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78:243–52. doi: 10.1086/500026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ackert-Bicknell CL, Karasik D, Li Q, Smith R, Hsu Y, Churchill GA, Paigen B, Tsaih S-W. Mouse BMD Quantitative Trait Loci Show Improved Concordance with Human Genome Wide Association Loci when Recalculated on a New, Common Mouse Genetic Map. J Bone Min Res. 2010 Feb 23; doi: 10.1002/jbmr.72 (p n/a). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishimori N, Stylianou IM, Korstanje R, Marion MA, Li R, Donahue LR, Rosen CJ, Beamer WG, Paigen B, Churchill GA. Quantitative Trait Loci for Bone Mineral Density in an SM/J by NZB/BlNJ Intercross Population and Identification of Trps1 as a Probable Candidate Gene. J Bone Miner Res. 2008 doi: 10.1359/JBMR.080414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beamer WG, Shultz KL, Donahue LR, Churchill G, Sen S, Wergedal JR, Baylink DJ, Rosen CJ. Quantitative trait loci for femoral and lumbar vertebral bone mineral density in C57BL/6J and C3H/HeJ inbred strains of mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16:1195–1206. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.7.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li R, Lyons MA, Wittenburg H, Paigen B, Churchill GA. Combining Data From Multiple Inbred Line Crosses Improves the Power and Resolution of Quantitative Trait Loci Mapping. Genetics. 2005;169:1699–1709. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.033993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Churchill GA, Doerge RW. Empirical Threshold Values for Quantitative Triat Mapping. Genetics. 1994;138:963–971. doi: 10.1093/genetics/138.3.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lander ES, Botstein D. Mapping Mendelian Factors Underlying Quantitative Traits Using RFLP Linkage Maps. Genetics. 1989;121:185–199. doi: 10.1093/genetics/121.1.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Broman KW, Wu H, Sen S, Churchill GA. R/qtl: QTL mapping in experimental crosses. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:889–890. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burgess-Herbert SL, Cox A, Tsaih S-W, Paigen B. Practical Applications of the Bioinformatics Toolbox for Narrowing Quantitative Trait Loci. Genetics. 2008;180:2227–2235. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.090175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu H, Mohan S, Edderkaoui B, Masinde G, Davidson H, Wergedal J, Beamer W, Baylink DJ. Detecting novel bone density and bone size quantitative trait loci using a cross of MRL/MpJ and CAST/EiJ inbred mice. Calcif Tissue Int. 2007;80:103–110. doi: 10.1007/s00223-006-0187-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ackert-Bicknell CL, Demissie S, Marin de Evsikova C, Hsu YH, DeMambro VE, Karasik D, Cupples LA, Ordovas JM, Tucker KL, Cho K, Canalis E, Paigen B, Churchill GA, Forejt J, Beamer WG, Ferrari S, Bouxsein ML, Kiel DP, Rosen CJ. PPARG by dietary fat interaction influences bone mass in mice and humans. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1398–408. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.080419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsu YH, Zillikens MC, Wilson SG, Farber CR, Demissie S, Soranzo N, Bianchi EN, Grundberg E, Liang L, Richards JB, Estrada K, Zhou Y, van Nas A, Moffatt MF, Zhai G, Hofman A, van Meurs JB, Pols HA, Price RI, Nilsson O, Pastinen T, Cupples LA, Lusis AJ, Schadt EE, Ferrari S, Uitterlinden AG, Rivadeneira F, Spector TD, Karasik D, Kiel DP. An integration of genome-wide association study and gene expression profiling to prioritize the discovery of novel susceptibility Loci for osteoporosis-related traits. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000977. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Y, Abecasis G. Mach 1.0: Rapid Haplotype Reconstruction and Missing Genotype Inference. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;S79:2290. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Y, Willer CJ, Ding J, Scheet P, Abecasis GR. MaCH: using sequence and genotype data to estimate haplotypes and unobserved genotypes. Genet Epidemiol. 2010;34:816–34. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abecasis GR, Willer C. Metal: Meta Analysis Helper. 1.0 14/4/2008. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Camp NJ, Farnham JM. Correcting for multiple analyses in genomewide linkage studies. Annals of human genetics. 2001;65:577–82. doi: 10.1017/S0003480001008922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao X, Starmer J, Martin ER. A multiple testing correction method for genetic association studies using correlated single nucleotide polymorphisms. Genet Epidemiol. 2008;32:361–9. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cox A, Ackert-Bicknell CL, Dumont BL, Ding Y, Bell JT, Brockmann GA, Wergedal JE, Bult C, Paigen B, Flint J, Tsaih SW, Churchill GA, Broman KW. A new standard genetic map for the laboratory mouse. Genetics. 2009;182:1335–44. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.105486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang X, Paigen B. Genetic Variation in HDL Cholesterol in Humans and Mice. Circ Res. 2005;96:27–42. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000151332.39871.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Masinde G, Li X, Gu W, Wergedal J, Mohan S, Baylink DJ. Quantitative trait loci for bone density in mice: the genes determining total skeletal density and femur density show little overlap in F2 mice. Calcif Tissue Int. 2002;20:209–215. doi: 10.1007/s00223-001-1113-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petkov PM, Ding Y, Cassell MA, Zhang W, Wagner G, Sargent EE, Asquith S, Crew V, Johnson KA, Robinson P, Scott VE, Wiles MV. An efficient SNP system for mouse genome scanning and elucidating strain relationships. Genome Res. 2004;14:1806–11. doi: 10.1101/gr.2825804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gai Z, Gui T, Muragaki Y. The function of TRPS1 in the development and differentiation of bone, kidney, and hair follicles. Histol Histopathol. 2011;26:915–21. doi: 10.14670/HH-26.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Momeni P, Glockner G, Schmidt O, von Holtum D, Albrecht B, Gillessen-Kaesbach G, Hennekam R, Meinecke P, Zabel B, Rosenthal A, Horsthemke B, Ludecke HJ. Mutations in a new gene, encoding a zinc-finger protein, cause tricho-rhino-phalangeal syndrome type I. Nat Genet. 2000;24:71–4. doi: 10.1038/71717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suemoto H, Muragaki Y, Nishioka K, Sato M, Ooshima A, Itoh S, Hatamura I, Ozaki M, Braun A, Gustafsson E, Fassler R. Trps1 regulates proliferation and apoptosis of chondrocytes through Stat3 signaling. Dev Biol. 2007;312:572–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Piscopo DM, Johansen EB, Derynck R. Identification of the GATA factor TRPS1 as a repressor of the osteocalcin promoter. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:31690–703. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.052316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Napierala D, Garcia-Rojas X, Sam K, Wakui K, Chen C, Mendoza-Londono R, Zhou G, Zheng Q, Lee B. Mutations and promoter SNPs in RUNX2, a transcriptional regulator of bone formation. Mol Genet Metab. 2005;86:257–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malik TH, Von Stechow D, Bronson RT, Shivdasani RA. Deletion of the GATA domain of TRPS1 causes an absence of facial hair and provides new insights into the bone disorder in inherited tricho-rhino-phalangeal syndromes. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:8592–600. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.24.8592-8600.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]