Cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs), also referred to as peptide transduction domains (PTDs), are polypeptide domains that can enter many, if not most, cell types. CPP/PTDs mediate transduction into cells of a wide range of cargos that otherwise lack bioavailability, such as peptides, proteins, antisense oligonucleotides, and small interfering RNAs. CPP/PTDs are thus being studied extensively as delivery agents for molecular therapies, and a variety of transducing peptides have now been identified, including both naturally occurring domains and synthetically derived sequences comprising polycationic or amphipathic residues.1 Although much progress has been made in understanding the endocytotic mechanisms by which CPP/PTDs enter cells,1 several important unanswered questions remain. In an upcoming issue of Molecular Therapy, Hirose and colleagues report a study in which they reexamined the direct membrane transduction mechanism of CPP/PTDs using highly sensitive imaging techniques and well-controlled experimental systems.2 The study reinforces the notion that CPP/PTDs enter cells by endocytosis (macropinocytosis), but it also highlights the significance of the specific peptide and cargo conditions that drive membrane deformations required for concomitant, low-level nonendocytotic uptake.

Almost 25 years ago, it was discovered that the transactivator of transcription (TAT) protein from the HIV virus, as well as a chemically synthesized version of TAT, could directly enter cells.3,4 Some years later it was found that a short arginine-rich sequence of TAT was sufficient to deliver or “transduce” macromolecular cargo into cells.5,6 In 1991, Prochiantz and colleagues found that a polypeptide from Antennapedia protein, a homeotic transcription factor from Drosophila, could also transduce into cells.7 A key question that arose from these findings the mechanism for this protein transduction activity. In the 1990s, most CPP/PTDs were presumed to enter cells by directly crossing the cellular membrane in an energy- and temperature-independent manner.8 In 2003, however, Lundberg et al. blew this notion apart by showing that the experimental basis for this proposition was a redistribution artifact caused by fixation before microscopy.9 This led to a rush of studies reexamining how CPP/PTDs enter cells. Although such studies showed that CPP/PTDs enter cells by some form of endocytosis, our laboratory first reported in 2004 that TAT enters cells by macropinocytosis, a specialized form of fluid-phase endocytosis that occurs in all cells10 (Figure 1). Futaki's laboratory reported that same year that octa-arginine (8R) also enters cells by macropinocytosis.11 In our hands, >95% of TAT plus peptide or protein cargos enter cells by macropinocytosis.12 However, there remain ~5% that either is within the error bar of the analysis or perhaps is an indication of a direct cell membrane transduction mechanism that has yet to be resolved.

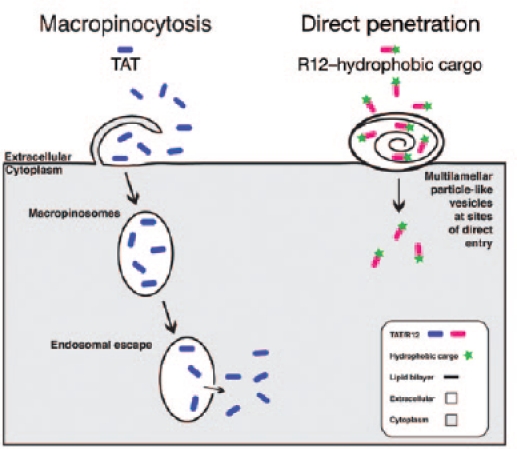

Figure 1.

Comparison of cell-penetrating peptide–uptake mechanisms. Transactivator of transcription (TAT) binds to the plasma membrane and enters the cells via macropinocytosis (left), followed by release into the cytoplasm. R12 (12 arginine residues) peptides with hydrophobic cargos directly penetrate the membrane (right) by inducing membrane deformations and multilamellar, particle-like structures at the site of entry.

In their new study, Hirose et al. propose that direct penetration of CPP/PTDs into cells does indeed exist but that (i) it requires a hydrophobic moiety (cargo) attached to the CPP/PTD and (ii) it occurs only at specific locations on the plasma membrane that are competent to induce multivesicular structures along with topical inversions. The investigators evaluated the effect of a somewhat long 12-arginine peptide (R12, as compared with 6 Arg in TAT or 8 Arg in R8) coupled to a hydrophobic Alexa488 fluorophore (R12-Alexa488) on the plasma membrane of HeLa cells.2 Utilizing confocal laser scanning microscopy and electron microscopy, the authors concluded that R12-Alexa488 enters cells by direct penetration at specific sites where small particle-like cell surface structures are formed. These structures appear to protrude out from the plasma membrane, resembling to some extent a membrane bleb.13 Indeed, the surrounding membrane shows signs of deformation and stains positive for annexin V, a specific phosphatidylserine-binding partner, suggesting some plasma membrane inversion at these R12-Alexa488-induced structures. Surprisingly, no leakage of lactate dehydrogenase from the cells was observed, indicating that the cells remain intact despite the severe membrane perturbations. Furthermore, LAMP-2, a marker of the membrane repair response,14 was detected on the plasma membrane in close proximity to these R12-Alexa488-induced structures.

In a startling observation through electron microscopy, the membrane structures were found to contain complex multilamellar lipid membranes (essentially layers of membranes) with internal hollow spaces, suggesting that the R12-Alexa488 peptide initiates gross membrane alterations. Time-lapse microscopy further showed that these structures form within minutes after addition of the R12-Alexa488 CPP/PTD. The R12-Alexa488-containing vesicles form a large punctuate pattern at the plasma membrane, followed by escape of the R12-Alexa488 into a more even distribution throughout the cytoplasm. Intriguingly, only R12-Alexa488 and R12–hemagglutinin tag were able to initiate the cell surface structures, whereas incubation with very high concentrations (100 µM) of R12 peptide alone did not—nor did a shorter arginine-rich control peptide, R4-Alexa488, suggesting that both peptide cationic arginine length and hydrophobicity of the small cargo are important for this direct-uptake mechanism. This highlights important considerations that must be taken into account with the use of CPP/PTDs conjugated to fluorophores and therapeutically relevant cargo.

Both Futaki's group and Brock's group15,16,17 have previously reported the direct membrane transduction of CPP/PTDs; however, what is unique here is (i) the requirement for a longer arginine-containing CPP/PTD coupled to a small hydrophobic cargo (Alexa488 or hemagglutinin tag) and (ii) the microscopy showing the presence of multilamellar lipid membranes structures at the site of entrance. However, these observations raise more questions than they resolve. First, similar to the studies here, over the years the vast majority of CPP/PTD-uptake studies looking at mechanism have relied on Alexa488 or fluorescein isothiocyanate dye–labeled CPP/PTDs and tended to lack phenotypic analysis of cargo function inside of the cells. Given the results here (and, of course, barring all studies that used fixation techniques), we need to question whether these prior studies may have been biased by the particular combinations of CPP/PTD and hydrophobic dye. Second, not all cells in a given population are susceptible to this type of direct-uptake mechanism. By contrast, cellular uptake of CPP/PTDs by macropinocytosis (endocytosis) results in transduction into the entire population of cells, with essentially the same amount of material present inside each cell. Does this suggest an unknown epigenetic contribution or a specific phase of the cell cycle or a definable amount of metabolism (cell growth)? Finally, is there evidence that it occurs in vivo in preclinical models (or in human clinical trials)? Although these will be very difficult experiments to design and control for, they will ultimately tell us whether the cell culture studies are directly related to how these molecules transduce into cells in preclinical animal models as well as in the more than 25 clinical trials using the TAT CPP/PTD.

In summary, the study by Hirose and colleagues brings new and useful information to the CPP/PTD field that illustrates the importance of confirming that the peptide and not the cargo is responsible for the observed mechanism(s) of cellular uptake. Although endocytosis may be responsible for the vast majority of CPP/PTD internalization, accumulating evidence suggests that direct penetration does occur at threshold concentrations. In conclusion, the influence of the cargo must be considered when comparing endocytosis and direct penetration, as the present study highlights, and could explain some of the discrepancies that have existed within the field of CPP/PTD uptake for well over 20 years.

REFERENCES

- Van den Berg A., and, Dowdy SF. Protein transduction domain delivery of therapeutic macromolecules. Curr Opin Biotech. 2011;22:888–893. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose H, Takeuchi T, Osakada H, Pujals S, Katayama S, Nakase I.et al. (2012Transient focal membrane deformation induced by arginine-rich peptides leads to their direct penetration into cells Mol Therin press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Frankel AD., and, Pabo CO. Cellular uptake of the tat protein from human immunodeficiency virus. Cell. 1988;55:1189–1193. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90263-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green M., and, Loewenstein PM. Autonomous functional domains of chemically synthesized human immunodeficiency virus tat trans-activator protein. Cell. 1988;55:1179–1188. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90262-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezhevsky SA, Nagahara H, Vocero-Akbani AM, Gius DR, Wei MC., and, Dowdy SF. Hypo-phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein (pRb) by cyclin D:Cdk4/6 complexes results in active pRb. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1997;94:10699–10704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vives E, Brodin P., and, Lebleu BA. Truncated HIV-1 Tat protein basic domain rapidly translocates through the plasma membrane and accumulates in the cell nucleus. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16010–16017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.25.16010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joliot A, Pernelle C, Deagostini-Bazin H., and, Prochiantz A. Antennapedia homeobox peptide regulates neural morphogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:1864–1868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.5.1864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derossi D, Joliot AH, Chassaing G., and, Prochiantz A. The third helix of the Antennapedia homeodomain translocates through biological membranes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:10444–10450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg M, Wikström S., and, Johansson M. Cell surface adherence and endocytosis of protein transduction domains. Mol Ther. 2003;8:143–150. doi: 10.1016/s1525-0016(03)00135-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadia JS, Stan RV., and, Dowdy SF. Transducible TAT-HA fusogenic peptide enhances escape of TAT-fusion proteins after lipid raft macropinocytosis. Nat Med. 2004;10:310–315. doi: 10.1038/nm996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakase I, Niwa M, Takeuchi T, Sonomura K, Kawabata N, Koike Y.et al. (2004Cellular uptake of arginine-rich peptides: roles for macropinocytosis and actin rearrangement Mol Ther 101011–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan IM, Wadia JS., and, Dowdy SF. Cationic TAT peptide transduction domain enters cells by macropinocytosis. J Control Release. 2005;102:247–253. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charras G., and, Paluch E. Blebs lead the way: how to migrate without lamellipodia. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:730–736. doi: 10.1038/nrm2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palm-Apergi C, Lorents A, Padari K, Pooga M., and, Hällbrink M. The membrane repair response masks membrane disturbances caused by cell-penetrating peptide uptake. FASEB J. 2009;23:214–223. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-110254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fretz MM, Penning NA, Al-Taei S, Futaki S, Takeuchi T, Nakase I.et al. (2007Temperature, concentration- and cholesterol-dependent translocation of - and -octa-arginine across the plasma and nuclear membrane of CD34+ leukaemia cells Biochem J 403335–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosuge M, Takeuchi T, Nakase I, Jones AT., and, Futaki S. Cellular Internalization and distribution of arginine-rich peptides as a function of extracellular peptide concentration, serum, and plasma membrane associated proteoglycans. Bioconjug Chem. 2008;19:656–664. doi: 10.1021/bc700289w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchardt F, Fotin-Mleczek M, Schwarz H, Fischer R., and, Brock R. A comprehensive model for the cellular uptake of cationic cell-penetrating peptides. Traffic. 2007;8:848–866. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]