Abstract

Research capacity building engenders assets that allow communities (and, in this case, student fellows) to respond adequately to health issues and problems that are contextual, cultural and historical in nature. In this paper, we present a US–South African partnership that led to research training for 30 postgraduate students at two South African universities. We begin by exploring the nature of research capacity building in a partnership research project designed to promote HIV and AIDS-related stigma reduction. We examine methodological issues and their relevance to training of postgraduate students in South Africa. We conclude with recommendations for a successful model of partnership for building capacity of health researchers in Africa with the goal of developing research that informs policies and helps to bridge the health inequity gap globally.

Keywords: capacity building, culture, empowerment, globalization, HIV/AIDS, participation, partnership, PEN-3 model, power

Introduction

Research capacity building in Africa is a key to achieving equity in global health. For example, research capacity building for Africans is critical for programmes and policies which target the reduction of HIV and AIDS. In response to this need, we developed a partnership between universities in South Africa and the United States in order to build capacity for intervention research and to establish and maintain a cadre of researchers whose work can inform policies and programmes specifically designed to reduce and eliminate HIV and AIDS-related stigma. Capacity building is the process of helping communities and organizations harness human, technical and financial resources, which allows them to respond adequately to health issues in ways that inform such policies (1,2). Capacity building was the most critical aspect of our research and training project. We applied a cultural model as we trained South African postgraduate students to study relationships in families and interactions in healthcare settings, with a specific focus on behaviours that are supportive or stigmatizing of persons living with HIV and AIDS. One of the keys to controlling HIV and AIDS is building research capacity to ensure that future generations of South Africans are trained on how to conduct stigma-related research to help reduce rising infection rates.

In this paper, we begin by providing some background on research capacity building and the relevance of a partnership project between the US and South Africa. We then compare published criteria for successful partnership against our programme in South Africa, which trained 30 postgraduate students at two historically disadvantaged South African universities, the University of the Western Cape (UWC) and University of Limpopo (UL), Turfloop Campus. Finally, we conclude with recommendations for capacity building for health researchers in Africa, with the goal of developing culture-based research that informs public policies.

Background

In the past few years, efforts in global health have increasingly underscored the importance of bridging the inequity gap in global health, and capacity building is believed to be the cornerstone to equity in global health (3). Adequate training and distribution of a healthcare workforce is reported to be central to the mission of global health (4,5). For example, building capacity for multidisciplinary research is believed to be central to achieving the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) by the 2015 deadline (6). Some scholars have hailed the eighth goal – establishing and sustaining global partnership for development – as critical to achieving the other goals. Concerns over the ability to achieve this goal focus primarily on the traditional nature of partnership between well-resourced nations or institutions and poorly resourced nations.

Although we focus on research capacity building in this paper, our experience is based on a five-year (2003–2008) HIV and AIDS-related stigma reduction study in South Africa. The overall goal of the project was to strengthen infrastructure and research capacity building at two universities. This included developing and sustaining culture-and gender-based interventions and conducting policy research for the elimination of stigma associated with HIV and AIDS prevention, care and support in South Africa. The partnership was forged to encourage postgraduate students at the two universities to consider, from cultural and gender perspectives, health behaviour and health promotion research on stigma related to HIV and AIDS in South Africa.

Implementation process

The project was funded by an initiative from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) that called for proposals for a research partnership between institutions in the US and South Africa. The goal of the proposal was research capacity building for South African postgraduate students and selected faculty mentors. A second goal was the use of the PEN-3 model (7) used by researchers to address health behaviours through cultural lenses.

Using PEN-3 became particularly important since the students who are the focus of interest in this study represent a population that is historically disadvantaged in South Africa. Therefore, the project’s central aim was to build the capacity of disadvantaged, under-served black (African and colouredi) postgraduate students at the two universities. The project was designed in such as way as to focus on one university (UWC) over a two-year period before transitioning to the second university (UL) for another two years. In the Western Cape, we focused on three communities, two of them predominately black (Khayelitsha and Gugulethu) and one predominately coloured (Mitchell’s Plain). In the Limpopo province the communities were predominately black. In the fifth year of the study, we brought both institutions together. In each of the first four years, two students from each university were paired with one faculty mentor from the same university. In the fifth year, we paired one student from each university with one faculty mentor from the same university.

Throughout the five years of the project, we focused on three groups of individuals critical to understanding HIV and AIDS-related stigma: family, healthcare providers, and people living with HIV and AIDS. The key focus of our partnership was to bring together students and faculty of diverse academic backgrounds for the research capacity-building aspects of our work. Our students were drawn from psychology, gender studies, public health and social work departments.

Each year, two workshops were conducted. The first workshop was held in the US in autumn to plan for the following year, with three primary purposes: to review project activities from the previous year and make needed adjustments, to develop and finalize the research timeline for the upcoming year, and to review student applications.

The second workshop was held in South Africa to train the selected students during the second week of January. During the five days of the workshop, lectures, group discussions, role-plays, video and personal testimonies of people living with HIV or AIDS were used to prepare students for their fieldwork. A timeline was developed and agreed upon and a data collection and analysis workshop was held before student researchers went into the community. Interview protocols that were developed for data collection were based on the PEN-3 model.

The PEN-3 model

PEN-3 is a cultural model that was developed to guide the development and implementation of cultural approaches to health promotion and health education programmes (7,8). The model advanced the premise that health knowledge, beliefs and behaviour are shaped by culture and hence the need to understand the cultural contexts of health. For example, in this project, stigma as a form of rejection of individuals and groups has a political history that makes the contexts of HIV and AIDS stigma in South Africa much more complex than may be observed in a different country. Using PEN-3, researchers are able to unpack political, historical and cultural roots of some of the behaviours that are observed to be stigmatizing of persons living with HIV and AIDS. PEN-3 has been used in research on cancer (9,10), hypertension (11) and diabetes (12). It has also been used to study smoking (13,14), food choices (15,16) and strategies to eliminate health disparities in obesity among US ethnic minorities (17).

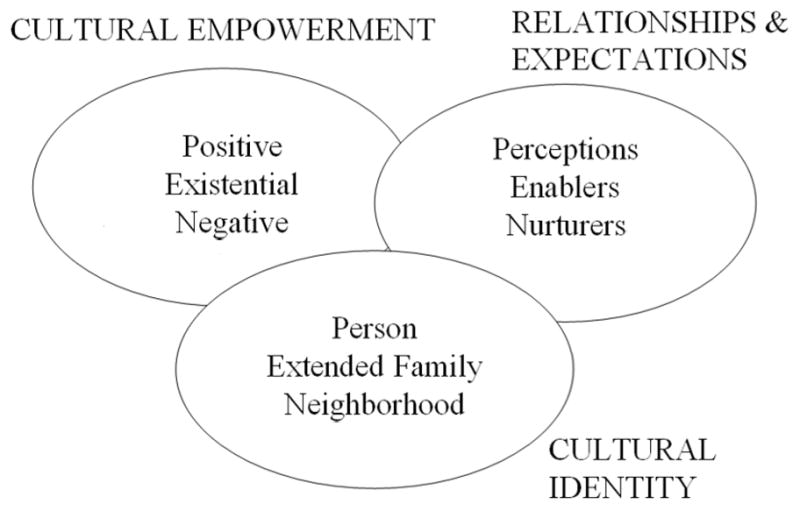

PEN-3 has three interrelated and interdependent dimensions: cultural identity (CI), relationships and expectations (RE) and cultural empowerment (CE) (7). Each dimension has three domains. The three domains of RE as applied in this project were: perceptions (beliefs and values held by people about an HIV and AIDS stigma); enablers (resources that promote or are not supportive of efforts at changing behaviours and contexts of HIV and AIDS stigma); nurturers (friends and family support or rejection of people living with HIV or AIDS). Three domains of CE as applied in this project were: positive (identifying supportive behaviours toward a person living with HIV or AIDS rather than focusing only on stigmatizing behaviours); existential (values and attributes that make the culture unique rather than blaming the culture for programme failure); negative (behaviours and contexts that contribute to HIV and AIDS stigma). The three domains of CI in this project were: person (focusing on the one person, such as a mother, who may have the most impact on HIV disclosure); extended family (the role of kinship in decisions about acceptance and rejection of a family member living with HIV and AIDS); neighbourhood (the context of the community and values that define acceptance and rejection). In the application of PEN-3, the two dimensions (and their three domains) of RE and CE are crossed to generate nine cells. In the final phase, and based on the three domains of CI, researchers return to the community to share their findings and further learn from the community before deciding where to begin the intervention. Identifying where to begin the intervention, based on the processes above, is referred to as ‘point of intervention entry’. This community engagement, in PEN-3, is central to the participatory method employed in our partnership for research capacity building.

Approaches to global partnership for capacity building

Capacity building and partnership are two vital initiatives whose combined effect holds enormous promise for sustainable health promotion in African countries. In health promotion, capacity building is an approach to developing skills that are sustainable with resources and a commitment to improve health within an organizational structure (18). A key to successful capacity building has been the development of strong partnerships. Addressing what makes a successful partnership in health programmes between multinational institutions (typically private and public), Buse and Harmer (19) identified some common criteria, or what they referred to as habits. In reviewing the key areas of partnership success, they identified seven critical factors. If left unaddressed, these factors were noted barriers to achieving true partnership. Below, we have listed the seven criteria and then provided examples of how we addressed each one in our project.

Donor/recipient goal alignment

A key factor in the success of our partnership was alignment in the vision shared by the co-principal investigators (co-PIs) in the US and South Africa. This shared vision was centred on a commitment to build and strengthen the capacity of postgraduate students in collaboration with their faculty mentors at two historically disadvantaged universities in South Africa. Our project was one of nine funded by the National Institutes of Health under a specific call for proposals to strengthen institutional partnerships between researchers in the US and Southern Africa. Of the nine projects funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under the programme announcements, this project was the only partnership in which funds were transferred quarterly from the fiduciary partner institution in the US directly to the South African institutional partner, as opposed to receipts being submitted before fund distribution. We agreed at the outset that, since the grant was funded based on shared partnership between the two institutions, a letter from the South African partner confirming the annual budget for the subcontract was sufficient to establish a quarterly transfer of funds based on the annual budget. Although the receipt-based transfer of funds that typifies most transatlantic partnerships stems from a need for accountability, the practice (though unintentional) often leads to an unnecessary sense of suspicion and distrust by African partners. Thus, trust was the hallmark on which our partnership was based.

Grant stakeholders a voice in decision making

On this project, there were multiple ways in which we offered opportunities for stakeholders to have a voice in our partnership. Stakeholders in our project included the leadership of the two universities and different community members who were represented on our community advisory board (CAB). At the beginning of the project, the two co-PIs met with the leadership of the two universities to explain the nature of our project and sought their guidance and support in gaining access to their faculty, staff and students. During these meetings, we explained the proposed project protocol and sought inputs for modifications. The protocol included making announcements on campus at the beginning of the project to recruit student fellows. A campus announcement was made annually regarding the selection of the six students to be trained during the year. A CAB was constituted for each site, and they met during the last day of our annual workshop in January. The CAB represented different constituencies in the community including people living with HIV or AIDS, civil society, traditional healers, youth organizations, women’s organizations and HIV and AIDS researchers in the university. During the workshop, the co-PIs and project director led the presentation of scheduled activities for the year. Beginning in the second year, one or two students were selected from the last cohort of trainees to make a board presentation on their accomplishments. Selecting board members with HIV and AIDS research backgrounds at the two universities was crucial for ensuring that we were sensitive to both research and cultural perspectives from each region. Although both universities are among the least resourced, they produce a majority of policy makers in the country. The historical policy influence of these institutions, coupled with the low number of South African blacks who are trained in health research, made both the culturally based framework of our research and the capacity-building goals of our project very important and timely.

Define partner roles and responsibilities

A management team was established to ensure smooth communication between research partners in the US and South Africa. The project director, who was a critical link between the partners, was crucial in coordinating between the two universities and ensuring a smooth transition from one year to another. One failure in our management system was that we had planned to meet quarterly by video conference, which did not happen. We therefore maximized our face-to-face time during the two annual meetings and otherwise used telephone and e-mail. Although the management team did not meet as regularly as planned, the specific definition of each team member’s role made it easier for issues to be addressed. The first year of the project provided us with the opportunity to establish benchmarks for monitoring expectations in roles and responsibilities. By the end of the second year, a quarterly evaluation form was developed as a mechanism by which faculty mentors could provide feedback on students’ progress. A quarterly reimbursement scheme, developed in collaboration with all mentors, was established for both mentors and students, with a yearly review for any relevant updates and revisions.

Understand the historical contexts

According to Buse and Harmer (19), examining historical contexts allows imbalances between public and private and/or privileged and under-resourced organizations to be better understood. They focused on the vilification of the public sector by the private sector in addressing this factor, and find that the public sector tends to be viewed as perpetually unresponsive to change, while the contexts of change or the shifting roles of power are not considered. While our partnership was not a public/private relationship, the parallel for our project is in the relationship between American institutions and South African institutions. The history of North–South relationships has been described in the words of the famous Malian historian, Ahmadou Hampate Ba, as ‘the hand that gives is always on top’ (7,p.6). African countries are often at the receiving end of international donor money, models, theories and logic for framing the solutions to problems. Unfortunately, when implementation fails, the receiver is typically blamed for the failure even though they are also the ones victimized. The tendency to blame the victim is even more common when historically disadvantaged recipient universities are the focus of capacity building. Capacity building in our project was as much about acquiring skills to conduct HIV and AIDS-related stigma research as it was about employing a theoretical model that allows these students and their mentors to create meaning based on experiences from their cultures and contexts. At our annual January workshops, we addressed issues of inequity in both resources and knowledge production and the impact they had on health. We used PEN-3 since it is a model that offers opportunities to address positive, existential and negative values (20,21) but with a particular emphasis on always seeking positive values in every context. This model provided students with the opportunity to address a whole range of beliefs, values and behaviours in families and healthcare settings. During each workshop in South Africa, personal testimonies on experiences with stigma were offered by persons living with HIV or AIDS. One aspect of capacity building that was very important in our project was the focus on a gender-based strategy for research. When personal testimony was offered by a woman living with HIV or AIDS, gender inequity became a visible example of how stigma differentially affects women compared to men. Also, role-playing during the workshop provided opportunities to demonstrate gender differences in HIV disclosure in the family.

Provide adequate funding

When we applied for our grant, we were funded at the level we requested and were also convinced that we had adequate funding for the project. However, within months, the value of the dollar against the South African rand dropped to a level that made it impossible to sustain the proposed number of trainees. Thus, it became necessary to reduce the number of trainees from eight, as we had originally proposed, to six students per year. We also had to reduce faculty mentors from four per year to three. Another challenge we faced was the amount of stipend we budgeted for South African students at a time when many NGOs, civil society and government offices were offering better compensation for the calibre of students we sought. The demand for a limited pool of eligible students, coupled with the strength of the rand against the dollar, made it necessary to readjust our stipend. For these students, who were mostly from historically disadvantaged backgrounds, the decision to accept a lower-paying research fellowship stipend over a higher-paying position in government or with an NGO was based solely on an interest in building research capacity.

Harmonize policies with practice

Consistent handling of procedures and practices by partners (both within and between countries) is absolutely crucial. In our experience, an unwavering sense of trust was the key to a successful partnership, which in turn was critical to a successful capacity-building project. With such a foundation, we were able to debate among ourselves about policies, practices and even methods of research. For example, we debated the role and use of qualitative methods such as focus group interviews in research. We discussed schools of thought suggesting that qualitative research should always be coupled with quantitative research, versus ours which affirms the independence of qualitative from quantitative research. We do note that one challenge we had was the limited number of publications generated over the five years of the project. Since the focus was on capacity building and developing basic research skills in student fellows, it took considerably longer than normal to generate publications, especially in the first two years when the emphasis was on qualitative research. We thus refined our approach in years three and four. The process of staging activities allowed us to be more focused and learn about similarities and differences between the universities and provinces so that strengths could be maximized.

Freedom to partner with others

Outside partnerships help leverage sustainability and we strongly encouraged them in our project. During the annual workshop in the US, South African partners were encouraged to meet with other researchers in the university to explore possible collaboration. In some cases, US partners arranged meetings for their South African partners with other colleagues at their university. This was reciprocated for US partners in South Africa. It also helped that two of our investigators had their own projects as principal investigators. During the initial planning phase of our project, a formal memorandum of understanding was drafted between our research agency partner (our primary partner) and one of our university partners, encouraging both institutions to collaborate on other projects that might or might not be related to our project. Presently, a formal written partnership exists between these two organizations, and this partnership has resulted in internship opportunities for students at the research agency based in South Africa as well as a research partnership opportunity for faculty members from the university based in the US.

Issues and challenges in capacity building for research

Capacity building as a strategy for strengthening institutions in poorly resourced countries is critical to sustainable health programmes. Building capacity for research in poorly resourced countries is likely to be sustainable if the mentoring process is anchored in an attitude of mutual respect, such that mentors and protégés share and learn from one another (6).

At the outset of our project, capacity building was framed as a bidirectional engagement of researchers and students whereby each person was prepared to both learn from and share experiences with one another. A key premise on which our partnership was based was collective decision making on trainee selection, mentoring and feedback processes. Another important premise was a high level of trust and respect for one another, even when we disagreed.

A key foundation for trust, as mentioned earlier, was that our partner in South Africa was not required to submit individualized receipts for activities related to the project in order to receive its budget allocation. Rather, our primary partner, the research agency, simply emailed a one-page invoice containing the amount that was agreed and the money was sent. This arrangement worked well, mostly due to the established financial accountability in place at the research agency. The agency’s audit system ensured that all disbursed funds were appropriately allocated and documented.

Capacity building in students

Research capacity building engenders assets that allow communities (and, in this case, student fellows) to respond adequately to health issues and problems that are contextual and historical in nature. Thus, building capacity simply means investing in the scholars of tomorrow. We began by defining the PEN-3 cultural model used in research capacity building as a key aspect to sustaining the interest of the students during the life of the project and beyond.

One of the student fellows reflected on ways in which the HIV and AIDS-related stigma research programme contributed to her personal development:

I have learnt computer skills like the NVivo program.

I have learnt to conduct focus groups of a sensitive nature, developing the skill of separating myself emotionally from the experience.

My listening and communication skills have been improved.

My writing skills have improved.

I have gained a better knowledge and understanding of HIV and AIDS and in particular the impact of HIV and AIDS on women.

As a woman I have learnt to appreciate my own health and to appreciate the things in life which I take for granted so easily.

I learnt that I have a contribution to make in improving the conditions of people living with HIV and AIDS and in particular the fight against stigma and discrimination.

Capacity building in faculty mentors

Perhaps the most important ingredient for achieving success in this project was the openness to learning and sharing among the faculty mentors and research team members. Other specific benefits that arose included faculty members at both South African universities beginning to serve as external examiners for each other’s institution. This was not the case previously. The level of openness and sincerity exhibited by the project partners made it easier for those who initially had some reservations to remain with the programme until they were not only convinced of its value, but became advocates for it.

For one colleague, it was not until a family member was diagnosed with HIV that the full impact of our programme was realized. His compelling testimony revealed a level of patience and commitment that both humbled all team members and deepened the sense of purpose for all participants. One faculty mentor who is also a co-author on this paper (TS) offered the following comments:

I had been working within the broad area of HIV and AIDS and gender for some time, but predominantly on issues relating to prevention and education (i.e. sexual practices, etc). Moving into the focus on responses to those living with HIV and AIDS and honing in on the gender stigmatization that is so prevalent in South Africa, as it is elsewhere, was an important extension of my own work. I have presented some of the findings of the study at two international conferences as well as a theoretical paper on gender and HIV stigma at a further conference, and am hoping to write some of this work up for publication in the near future.

Although the emphasis was research capacity building for students, mentors had the opportunity to strengthen their research capacity as well. For example, mentors learnt to use NVivo to organize qualitative research and STATA for quantitative data analysis.

For the US partners, the lessons learnt in the research capacity-building project were invaluable. Following feedback from student fellows during the training workshop in January about difficulties in understanding the accents of US faculty researchers, faculty modulated speech by speaking slowly during their lectures. They also learnt to contextualize their examples to ensure that South African students could relate to them. The South African examples they used during the workshop helped to broaden and enrich their teaching in the US. The role-play exercises were particularly revealing in terms of the cultural nuances expressed by students. One example was a foreign researcher who totally misunderstood the responses given to her interview questions because of her unfamiliarity with the cultural layers, codes and meanings of language. The response ‘My husband does not come home to eat my food’ was misinterpreted as meaning her spouse stays out late and does not eat at home. Rather, the absence of intimacy with her husband was the point of the woman’s response.

Finally, the genuine sense of a desire to learn expressed by the South African students was found to be most refreshing. Their institutions may be described as disadvantaged due to historical and political arrangements, but their attitude to learning is quite rich.

Key factors responsible for our successful partnership

Although we presented seven published criteria for successful partnership and provided examples on how our partnership responded to each criterion, we believe that our successful partnership for capacity building can be summarized in these three values:

The learning and sharing dynamic. The project was approached with an attitude of humility: each person believed that they had the potential to learn as much as they shared in the project. Participants functioned both as students and teachers at the same time, regardless of the level of experience and skills.

Trust and openness to differences. Our common goal in this partnership was to have a better understanding of stigma, not only for its relevance to HIV and AIDS, but also for its relevance to the multiple identities and contexts that are the reality of the new South Africa. A non-judgemental attitude was a key value.

Shared appreciation for both qualitative and quantitative research. The methods are markedly different but both have value in the pursuit of intellectual inquiry, as evident in publications of findings from the project. Key findings include: the complexity of stigma anchored in culture (21); roles of family in stigma (22), particularly as it relates to the agency of motherhood relative to HIV disclosure in the African cultural context (23); and the role food plays in understanding rejection and acceptance within healthcare institutions (24).

Capacity building that is connected with research on stigma offers a window into culture and provides an opportunity for students to become interested in scholarly pursuits. Increasing the pool of trained young South African researchers is the cornerstone to this research capacity-building project.

Conclusion

The lack of attention to capacity building often results in superficial participation in solutions to problems, given the absence of a sense of ownership in the population of interest (25). Capacity building and partnership tend to work hand in glove. When planned well, partnerships between institutions in the West and Africa can be well balanced and based on mutual respect and openness to learning from each other. Such partnership is central to effective capacity building for research.

It has been emphasized that the lack of research capacity in Africa remains an unmet challenge that must be addressed, particularly in the area of health research (6). Capacity building in this project provided opportunities for students in South African universities to develop research skills to tackle HIV and AIDS in their country. The skills they developed can help position them to make important contributions towards preventing HIV. To this end, a successful partnership for capacity building is a model for sustainable health programmes in South Africa.

Figure 1.

The PEN-3 model.

Source: Reference 7

Footnotes

Reprints and permissions: http://www.sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1757975911404745 http://ghp.sagepub.com

For a conceptualization of coloured identities in Western Cape Province, see 26.

References

- 1.Haines A, Sanders D. Building capacity to attain the Millennium Development Goals. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2005;99:721–726. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones DS, Tshimanga M, Woelk G, Nsubuga P, Sunderland NL, Hader SL, St Louis ME. Increasing leadership capacity for HIV/AIDS programmes by strengthening public health epidemiology and management training in Zimbabwe. Hum Resour Health. 2009;10(7):69. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-7-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson D, Raine KD, Plotnikoff RC, Cook K, Barrett L, Smith C. Baseline assessment of organizational capacity for health promotion within regional health authorities in Alberta, Canada. Promot Educ. 2008;15(2):6–14. doi: 10.1177/1025382308090339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koplan JP, Bond TC, Merson MH, Reddy KS, Rodriquez MH, Sewankambo NK, Wasserheit JN. Towards a common definition of global health. Lancet. 2009;373:1–3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60332-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leowski J, Krishnan A. Capacity to control non-communicable diseases in the countries of South-East Asia. Health Policy. 2009;92:43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lansang MA, Dennis R. Building capacity in health research in the developing world. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:764–770. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Airhihenbuwa CO. Healing our differences – the crisis of global health and the politics of identity. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Airhihenbuwa CO. Perspectives on AIDS in Africa: strategies for prevention and control. AIDS Educ Prev. 1989;1(1):57–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abernethy AD, Magat MM, Houston TR, Arnold HL, Jr, Bjorck JP, Gorsuch RL. Recruiting African American men for cancer screening studies: applying a culturally based model. Health Educ Behav. 2005;32(4):441–451. doi: 10.1177/1090198104272253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erwin DO, Johnson VA, Trevino M, Duke K, Feliciano L, Jandorf L. A comparison of African American and Latina social networks as indicators for culturally tailoring a breast and cervical cancer education intervention. Cancer. 2007;(2 Suppl):368–377. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walker C. An educational intervention of hypertension management in older African Americans. Ethn Dis. 2000;10:165–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodman RM, Yoo S, Jack L. Applying comprehensive community-based approaches in diabetes prevention: rationale, principles, and models. J Pub Health Manag Pract. 2006;12(6):545–555. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200611000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beech BM, Scarinci IC. Smoking attitudes and practices among low-income African Americans: qualitative assessment of contributing factors. Am J Health Promot. 2003;17(4):240–248. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-17.4.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scarinci IC, Silveira AF, Figueiredo dos Santos D, Beech BM. Sociocultural factors associated with cigarette smoking among women in Brazilian worksites: a qualitative study. Health Promot Int. 2007;22:146–154. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dam012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Underwood S, Pridman K, Brown L, Clark T, Frazier W, Limbo R, Schroeder M, Thoyre S. Infant feeding practices of low-income African American women in a central city community. J Community Health Nurs. 1997;14(3):189–205. doi: 10.1207/s15327655jchn1403_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.James DC. Factors influencing food choices, dietary intake, and nutrition-related attitudes among African Americans: application of a culturally sensitive model. Ethn Health. 2004;9(4):349–367. doi: 10.1080/1355785042000285375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumanyika SK, Obarzanek E. Pathways to obesity prevention: Report of a National Institutes of Health workshop. Obes Res. 2003;11:1263–1274. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barry MM. Capacity building for the future of health promotion. Promot Educ. 2008;15(4):56–58. doi: 10.1177/1025382308097700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buse K, Harmer AM. Seven habits of highly effective global public-private health partnerships: practice and potential. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:259–271. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Airhihenbuwa CO. On being comfortable with being uncomfortable: Centering an Africanist vision in our gateway to global health. 2005 SOPHE Presidential Address. Health Educ Behav. 2007;34 (1):31–42. doi: 10.1177/1090198106291377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Airhihenbuwa CO, et al. Stigma, culture, and HIV and AIDS in the Western Cape, South Africa: an application of the PEN-3 cultural model for community based research. J Black Psychol. 2009;35(4):407–432. doi: 10.1177/0095798408329941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iwelunmor J, Airhihenbuwa CO, Okoror TA, Brown DC, BeLue R. Family systems and HIV/AIDS in South Africa. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2007;27(4):321–335. doi: 10.2190/IQ.27.4.d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iwelunmor J, Zungu N, Airhihenbuwa CO. Rethinking HIV/AIDS disclosure among women within the context of motherhood in South Africa. Am J Pub Health. 2010;100(8):1393–1399. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.168989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okoror TA, et al. “My mother told me I must not cook any more”: food, culture, and the contexts of HIV and AIDS related stigma in three communities in South Africa. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2008;28(3):201–213. doi: 10.2190/IQ.28.3.c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Solomon Y, Ballif-Spanvill B, Ward C, Fuhriman A, Widdision-Jones K. The dynamics of community and NGO partnership: primary health care experiences in rural Mali. Promot Educ. 2008;15(4):32–37. doi: 10.1177/1025382308097696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erasmus Z, Pieterse E. Conceptualising Coloured identities in the Western Cape Province of South Africa. In: Palberg M, editor. National identity and democracy in Africa. Cape Town: Human Sciences Research Council and Mayibuye Centre of the University of the Western Cape; 1999. pp. 167–187. [Google Scholar]