Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this paper is to identify risk factors for cardiovascular disease in women with breast cancer and review healthy lifestyle behaviors as essential risk reduction strategies.

Findings

Women with breast cancer account for 22% of the 12 million cancer survivors. Women diagnosed with breast cancer often present with modifiable and non-modifiable cardiovascular risk factors and/or pre-existing co-morbid illness. Any one or a combination of these factors may increase the risk of cardiovascular disease. There is strong evidence that healthy eating and routine physical activity can reduce cardiovascular disease. Exercise improves cardiovascular fitness, body composition and quality of life in breast cancer survivors and observational studies suggest a survival benefit.

Clinical Implications:

Lifestyle interventions including a healthy diet, regular physical activity, weight management and smoking cessation should be integrated into a survivorship care plan to reduce cardiovascular disease risk and promote better health for women with breast cancer.

Keywords: Breast cancer survivor, cardiovascular risk, lifestyle behaviors, health promotion.

INTRODUCTION

Among women of all ages in the United States, cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death [1]. When compared to cancer in women, heart disease ranks as the second leading cause of death for women 45-79 years of age [2]. Yet, for selected cancers, such as breast cancer with improved survival outcomes, competing causes of death have contributed to an increase in all-cause mortality [3-5]. There are nearly 12 million cancer survivors in the United States (US) with breast cancer accounting for 41% of female survivors and 22% of all survivors. With 261,100 new cases of breast cancer (invasive and in-situ) estimated to be diagnosed in 2010 [2], the number of breast cancer survivors can be projected to increase over the next decade. Advances in cancer treatment resulting in long term survivorship and cardiotoxicity associated with adjuvant breast cancer therapy, the risk of cardiovascular disease has been cited as higher than risk of breast cancer recurrence [6] and death from heart disease is more common now than deaths attributed to breast cancer among survivors [3, 7]. Many of the risk factors associated with cardiovascular disease are modifiable. Healthy lifestyle behaviors are the foundation for risk reduction for primary and secondary prevention [8]. The purpose of this paper is to emphasize the role of lifestyle interventions for breast cancer survivors at risk for cardiovascular disease due to non-breast and breast cancer treatment related risk factors. The paper will review modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease in women, identify the need for cardiovascular risk assessment in women with breast cancer, describe breast cancer treatment related sequelae that contribute to reduced cardiovascular fitness and review the effectiveness of lifestyle interventions as a cardiovascular risk reduction and breast cancer survivor health promotion strategy.

RISK FACTORS OF CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE IN MID-LIFE AND OLDER WOMEN

Overweight, obesity, abdominal adiposity, cigarette smoking, sedentary behavior, hypertension, impaired glucose tolerance, and abnormal cholesterol are known modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) in women [9, 10]. The epidemic trend of overweight and obesity among women in the US is contributing to an increased risk of CVD, diabetes, hypertension, decreased physical function and metabolic syndrome [1, 11, 12], all of which are inter-related and significantly contribute to morbidity and mortality. Depression may have an indirect effect on CVD [1], and is associated with obesity, sedentary behavior, and poorer quality of life [13, 14]. Lifestyle interventions, specifically, healthy eating and regular physical activity, can prevent or modify these CVD risk factors [1, 8, 15, 16].

NEED FOR CARDIOVASCULAR RISK ASSESSMENT IN BREAST CANCER SURVIVORS

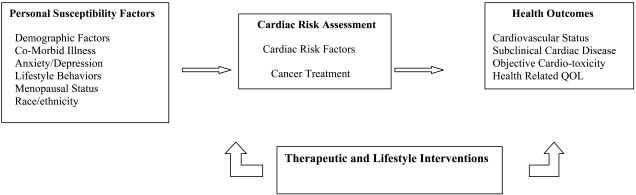

Women diagnosed with breast cancer may be at risk for cardiac disease unrelated to cancer treatment. Forty percent of women by 50 years of age in the US population have at least one cardiac risk factor and 17% have 2 or more risk factors, increasing their lifetime risk of developing cardiovascular disease. As the majority of women are diagnosed with breast cancer after the age of 45 years, a cardiovascular risk assessment is indicated even if women are asymptomatic [17-19]. Women with newly diagnosed breast cancer often present with modifiable CVD risk factors (e.g. overweight, obesity, sedentary behavior), non-modifiable risk factors (e.g. race, family history heart disease) and/or pre-existing chronic illness (e.g. valvular disease, hypertension, arrhythmias, diabetes) [20-25]. Any one or a combination of these factors increases a woman’s vulnerability to developing CVD and may enhance risk of cardiovascular complications from cancer therapy Fig. (1). Pre-existing diabetes in breast cancer survivors has been associated with increased treatment toxicity and reduced survival [26-28]. Hypertension has been reported as the most common co-morbid condition in cancer patients [29, 30], has been identified as a risk factor for developing anthracycline cardiotoxicity [21, 24], a risk factor for trastuzumab toxicity [22], is associated with a poorer prognosis especially in African American breast cancer survivors [31] and has emerged as a significant side effect of targeted breast cancer agents [6, 32, 33]. A “multiple hit” hypothesis has been proposed by Jones and colleagues [18] which suggests that the presence of cardiovascular risk factors increases the risk of developing cancer treatment associated cardiotoxicity and cancer treatment can independently cause cardiovascular injury. Cancer treatment may exacerbate underlying heart disease [6, 24, 25] and result in additive cardiac compromise [18, 20]. Comparing breast cancer survivors to age matched controls, breast cancer survivors were reported to have lower cardiac reserve, cardiovascular fitness, and HDL levels, and higher resting heart rate [34, 35]. Reduced cardiovascular reserve may increase a woman’s long term risk of CVD [34].

Fig. (1).

Model of Cardiac Vulnerability in Women with Breast Cancer: Opportunity for Intervention.

While some data exist on co-morbid conditions in newly diagnosed women with breast cancer [29, 36], the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in this population has not yet been systematically collected [18]. A baseline cardiac assessment prior to breast cancer therapy is essential [20]. Cardiovascular risk assessment prior to adjuvant breast therapy identifies level of risk and provides data to target interventions, specifically Class I lifestyle interventions and pharmacologic interventions where indicated [1, 17]. Screening for psychosocial distress in women at risk for or with cardiovascular disease is also recommended [37]. Anxiety and depression are associated with poorer outcomes [14, 38-41] and younger women appear more vulnerable [14]. Risk of depression among cancer survivors is estimated to be 10-25%, and younger breast cancer survivors have poorer adjustment and quality of life compared to older women [42]. The contribution of personal susceptibility factors and pre-existing cardiac risk factors for women who are to receive cardiotoxic cancer therapy has yet to be fully elucidated but an increased vulnerability for adverse cardiac outcomes has been suggested [18, 20, 24]. It is a critical time for cardiology and oncology to collaborate to identify and develop interventions for women newly diagnosed with breast cancer in the presence of cardiac risk factors if our goal is to enhance the quality of life for cancer survivors and decrease morbidity and mortality [43-46] Fig. (1).

THE EXPERIENCE OF ADJUVANT BREAST CANCER THERAPY

Adjuvant breast treatment includes chemotherapy, endocrine therapy and targeted agents. There is a wide variety of symptoms, many of which persist once the treatment ends [47]. Fatigue, sleep disturbance, musculoskeletal complaints, weight gain, treatment induced menopausal symptoms, cognitive changes, bone loss, painful peripheral neuropathy, anxiety, depression and fear of recurrence are common [48-59]. Women during cancer therapy decrease their levels of physical activity [60] and the de-conditioning effects of inactivity during and after therapy may further contribute to fatigue, sleep disturbances, weight gain, body composition changes, changes in insulin sensitivity, muscle atrophy, and decreased cardiovascular fitness.

Weight gain during and after breast cancer treatment is common [61, 62] and has been associated with an increased risk of recurrence and lower survival [63]. Several studies have reported body composition changes in breast cancer survivors, specifically increases in body fat and decreases in lean muscle mass over time [60, 63-66] and adjuvant Tamoxifen has been associated with increases in percent body fat [64, 67]. Early reports on weight gain in breast cancer survivors documented average gains of 14-17 pounds [57, 68]. Although continued research suggests that gains of 5-14 pounds are more common, the weight gain persists and has reported to increase over time after therapy [61, 62, 69, 70]. In a sample of 190 women with breast cancer who received adjuvant therapy, 71% gained an average of 3.7 kg in the year following therapy and among the women who lost weight in year one, 43% of them gained in years 2 and 3, exceeding their pre-treatment weight [70]. Continued weight gain in the years after adjuvant treatment may reflect societal trends in mid life and older women and may be associated with endocrine therapy, although the data are inconsistent to support the common complaints from women about weight gain and Tamoxifen.

Elevation in the systemic inflammatory marker, hsCRP, and central obesity have been associated with the development of metabolic syndrome in breast cancer survivors [71] both of which are considered significant cardiovascular risk factors [72, 73]. Monitoring weight and body composition, especially central adiposity, among breast cancer survivors is essential to target interventions [74].

The contribution of menopause to cardiovascular risk is a complex blend of chronological aging and ovarian aging [75]. While the evidence for decreased estrogen levels as a cardiac risk factor, either gradually with natural menopause, abruptly with chemotherapy induced menopause or with Aromatase Inhibitor therapy is controversial, it is strongly suggested to screen and monitor peri and postmenopausal women [75-77]. In one study with pre-menopausal women diagnosed with breast cancer who experienced amenorrhea with adjuvant therapy, there was a significant change in lipids, cholesterol, LDL, HDL and Lpa [78]. Cancer survivors are concerned about reducing their cancer recurrence risk but are also concerned about preventing morbidity and mortality from other chronic illness, such as heart disease [59]. The combination of drug induced menopause, effects of endocrine therapies and weight gain among breast cancer survivors underscores the unique potential cardiovascular disease risks for this population.

Cardiotoxicity associated with agents used in adjuvant breast cancer therapy has been well described [6, 18, 22, 24, 33, 79, 80]. In addition to the known Type I cardio-toxicity associated with anthracyclines [79], the use of targeted agents that alter genetic pathways and cellular functions has dramatically expanded the scope of cardiovascular effects of breast cancer therapy [6, 33, 80-83]. Measurement of left ventricular function (LVEF) is the standard of assessment for cancer treatment related cardiotoxicity but has failed to identify subclinical disease. The consequences of asymptomatic LVEF decline on long term cardiac function are essentially unknown [6, 35] and there is a critical need to identify patients with sub-clinical disease at higher risk of adverse cardiac outcomes [84]. Susceptibility to cardiac complications in cancer survivors is multifactorial [33] and requires the scientific and clinical knowledge of specialists in cardiology and oncology [6, 45, 85]. There is a gap in our understanding of the interplay of cardiovascular disease risk, cardiotoxicity and cardiac outcomes in cancer survivors. Identification of patients at risk for cardiac complications would direct risk reduction and therapeutic cardioprotective interventions to reduce morbidity and mortality [6, 24, 44, 86]. While we await data from needed prospective studies to better identify patients at risk for cardiac complications, lifestyle interventions have known health benefits for breast cancer survivors and mid-life women at risk for cardiovascular disease.

LIFESTYLE INTERVENTIONS FOR CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE RISK REDUCTION

Ideal cardiovascular health includes total cholesterol <200 mg/dL, blood pressure < 120/80, fasting blood glucose < 100 mg/dL, body mass index <25 kg/m2, no cigarette smoking, healthy diet, and regular physical activity of ≥ 150 minutes a week of moderate intensity or ≥ 75 minutes//week of vigorous intensity or a combination of intensities [1, 6]. Dietary guidelines for healthy eating for risk reduction for CVD, diabetes and cancer include a diet rich in whole grains and legumes with 5 servings of fruits and vegetables per day and limited intake of red meat, processed meats, alcohol and sugar sweetened beverages [87, 88]. There is strong epidemiologic data supporting the association of physical activity and healthy eating and lower risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes in women [8]. Aerobic exercise at the recommended guideline of 30 minutes 5 days per week has also been shown to improve blood pressure [89], improve insulin sensitivity [90, 91] and result in better cardio-respiratory fitness [9, 91, 92]. This level of exercise intensity can maintain weight but for women who desire to lose weight, exercise at a moderate-vigorous intensity 60 minutes per day is required, and preferentially combined with calorie restriction [9, 16]. To achieve ideal cardiovascular health or reduce risk factors, Artinian and colleagues [15] comprehensively reviewed the research on physical activity and healthy eating in relationship to CVD risk reduction and provide evidence based recommendations for practice. To promote adoption and adherence to the recommended guidelines for physical activity and healthy eating, goal setting, motivational strategies, reinforcement, feedback, and problem solving skills are identified as key strategies to support healthy lifestyle behaviors [15]. The authors also stress the importance of considering culture, ethnicity and socioeconomic factors in healthy lifestyle interventions [15] as changing one’s behavior is complex and approaches need to be tailored to specific populations to increase adherence and success [93].

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND BREAST CANCER SURVIVORS

Data from six observational studies concluded that moderate exercise (3-5 hours/week) improved all cause mortality in breast cancer survivors [94-99]. Multiple meta-analyses and systematic reviews of exercise interventions in breast cancer survivors over the past decade have reported improved cardiovascular fitness, body composition, quality of life, psychological adjustment, aerobic capacity, muscle strength and a decrease in fatigue, depression, anxiety, and sleeping disturbance [100-109]. Jones and colleagues [110] reviewed studies from 2002-2009 that systematically assessed cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) with peak oxygen consumption and reported a statistically significant improvement in CRF for supervised exercise training compared to control groups. Overweight and obesity remain significant risk factors for breast cancer survivors and are associated with increased risk of breast cancer recurrence [111] and higher mortality risk [4, 26, 112]. In a review of 24 randomized controlled exercise trials from 1998-2008, 44% reported improvement in body composition (e.g. less fat mass, increased lean muscle mass) [108]. Waist circumference is a well established measure of abdominal fat in cardiology, and can significantly predict women at higher cardiovascular risk even for those women within normal weight ranges [10]. While many breast cancer exercise trials have evaluated body composition, few have specifically reported changes in waist circumference. Cheema et al. [113] reported on a pilot aerobic resistance exercise study in women with breast cancer and waist circumference decreased after 8 weeks of exercise with no change in weight. While more sophisticated measures of body composition, such as whole body DEXA scans, may be preferred by researchers, waist circumference is a simple and reliable measure that can be incorporated into research and clinical practice.

More than half of women diagnosed with breast cancer who have participated in exercise trials have been overweight and some obese, reflecting a similar pattern of weight to women without breast cancer in the US. Only a few trials have investigated diet and exercise as an intervention for weight loss in breast cancer survivors [114-117]. Data from one trial [114] has supported the translation to an institutional clinical program [118] but randomized controlled trials are needed that combine physical activity and diet, if we are to influence the chronic illness risks of overweight and obesity on morbidity and mortality for women with breast cancer [74, 119].

SUMMARY

Lifestyle interventions are strongly recommended for breast cancer survivors [6, 21, 22, 32, 45, 120] for health promotion and risk reduction related to chronic illness. Recognizing the relationship of risk factors across chronic illness, the American Cancer Society (ACS), the American Heart Association (AHA) and the American Diabetes Association (ADA) set forth a common agenda for healthy lifestyle behaviors to reduce health risks at primary, secondary and tertiary levels [87]. Lifestyle interventions to reduce cardiovascular risk in women includes smoking cessation, a healthy diet, regular physical activity and weight management [1] and are directly applicable to breast cancer survivors Table (1). Physical activity recommendations by the American College of Sports Medicine for cancer survivors [121] are consistent with the American Heart Association guidelines for secondary prevention [1, 8, 16] and the United States Department of Health and Human Services [122]. For research and for clinical rehabilitation, fitness providers must be knowledgeable about the effects of cancer treatment on the ability to engage in exercise [121]. Persistent symptoms of therapy such as peripheral neuropathy [55], arthralgias [123], decreased cardiovascular reserve [18] and fatigue [124] are common and need to be incorporated into an individual prescription for an exercise program. Overweight and obesity present unique challenges to lifestyle behavior change and are often associated with chronic conditions such as knee osteoarthritis, diabetes and hypertension. Communication between oncology and cardiology in recommendations of lifestyle interventions for breast cancer survivors experiencing late effects such as decreased left ventricular function is critical to establish the best approach to individualized patient management. Finally, qualified providers for physical rehabilitation, such as physical therapists, fitness trainers in the community and clinical oncology researchers should be familiar with guidelines for exercise testing prior to implementing a physical lifestyle interventions in cancer survivors [121, 125]. Lifestyle behavior change is challenging, and maintenance of behavioral change has been shown to be quite difficult for the majority of persons. We, as oncology and cardiology providers, should establish a strong collaborative team between the patient, us and the physical fitness experts in enrolling patients in lifestyle intervention clinical trials and in promoting healthy living survivor programs in clinical practice.

Table 1.

Recommendations for Lifestyle Behaviors for Cardiovascular Risk Reduction in Women with Breast Cancer

| Lifestyle Behavior | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Cigarette smoking | Women should avoid tobacco smoke in the environment and should quit smoking if a smoker. Refer for counseling, behavioral programs and/or pharmacotherapy. |

| Diet | Fruits and vegetables ≥4.5 cups/day |

| Fish Twice a week | |

| Fiber 30 g/day | |

| Whole grains 3/day | |

| Nuts, legumes, seeds ≥ 4/week | |

| Saturated fat < 7% total energy intake | |

| Cholesterol < 150mg/day | |

| Alcohol ≤ 1/day | |

| Sodium <1500mg/day | |

| Trans-fatty acids 0 | |

| Sugar-sweetened beverages ≤36 oz/week | |

| Physical Activity | Minimum goal for women: 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise or 75 minutes vigorous exercise per week and muscle-strength exercises on 2-3 days per week. For optimal cardiovascular benefit, recommend 30 minutes of moderate aerobic physical activity most days of the week in episodes of at least 10 minutes each. |

| Women who need to lose weight, 60-90 minutes of at least moderate-intensity activity preferably on every day of the week is recommended. Consider referral to established programs to assist women in goal setting, problem solving skills, self monitoring, adherence and relapse prevention. Encourage women to enroll in physical activity intervention trials. | |

| Weight Management | Goal is BMI < 25kg/m2 and waist circumference < 35 inches. |

| Energy balance is the key to weight loss or maintaining current weight and requires a balance of physical activity and calorie intake. Refer women for consultation on healthy eating and energy balance. Encourage cancer survivors to enroll in weight management clinical trials. | |

| Psychological Well-being | Breast cancer survivors should be screened for psychological distress as anxiety and depression may increase cardiovascular risk, adversely affect their recovery and decrease overall quality of life. Provide women information about normal psychological reactions to diagnosis and treatment and discuss referral for counseling and exercise. |

REFERENCES

- 1.Mosca L, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, Bezanson JL, Dolor RJ, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Effectiveness-based guidelines for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in women 2011 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123 doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31820faaf8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chapman JW, Meng D, Shepherd L, Parulekar W, Inge JN, Muss H, et al. Competing causes of death from a randomized trial of extended adjuvant endocrine therapy for breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:252–260. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nichols HB, Trentham-Dietz A, Egan KM, Titus-Ernstoff L, Holmes MD, Bersch AJ, et al. Body mass index before and after breast cancer diagnosis associations with all cause breast cancer and cardiovascular disease mortality. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:1403–1409. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patnaik JL, Byers T, DiGuiseppi C, Denberg TD, Dabelea D. The influence of co-morbidities on overall survival among older women diagnosed with breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:1101–1111. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maurea N, Coppola C, Ragone G, et al. Women surviving breast cancer but fall victim to heart failure the shadows and lights of targeted therapy. J Cardiovasc Med. 2010;11:861–868. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0b013e328336b4c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patnaik JL, Byers T, DiGuiseppe C, Dabelea D, Denberg TD. Cardiovascular disease competes with breast cancer as the leading cause of death for older females diagnosed with breast cancer a retrospective cohort study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;13:R64. doi: 10.1186/bcr2901. https: //breast-cancer-research.com/content/13/3/R64 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lloyd-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, Mozaffarian D, Appel LJ, VanHorn L, et al. Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction The American Heart Association's strategic impact goals through 2020 and beyond. Circulation. 2010;121:586–613. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee VL, Foody JM. Women and heart disease. Cardiol Clin. 2001;29:35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang C, Rexrode KM, vanDam RM, Li TY, Hu FB. Abdominal obesity and risk of all cause cardiovascular and cancer mortality. Circulation. 2008;117:1658–1667. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.739714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome An American Heart Association National Heart Lung and Blood Institute scientific statement executive summary. Circulation. 2005;112:e285–e290. [Google Scholar]

- 12.deGonzalez A, Hartge P, Cerhan JR, Flint AJ, Hannan L, MacInnis RJ, et al. Body-mass index and mortality among 1.46 million white adults. New Engl J Med. 2010;363:2211–2219. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vaccarino V, McClure C, Johnson D, Sheps DS, Bittner V, Rutledge T, et al. Depression the metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk. Psychosomatic Med. 2008;70:40–48. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31815c1b85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beckie TM, Fletcher GF, Beckstead JW, Schocken DD, Evans ME. Adverse baseline physiological and psychosocial profiles of women enrolled in a cardiac rehabilitation clinical trial. J Cardiopulmonary Rehab Prev. 2008;28:52–60. doi: 10.1097/01.HCR.0000311510.16226.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Artinian NT, Fletcher GF, Mozaffarian D, Kris-Etherton P, VanHorn L, Lichetenstein AH, et al. Interventions to promote physical activity and dietary lifestyle changes for cardiovascular risk factor reduction in adults a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;122:406–441. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181e8edf1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haskell WL, Lee I, Pate RR, Powell KE, Blair SN, Franklin BA, et al. Physical activity and public health. Updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Circulation . 2007;116 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.185649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berger JS, Jordan CO, Lloyd-Jones D, Blumenthal RS. Screening for cardiovascular risk in asymptomatic patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;531:169–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.09.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones LW, Haykowsky MJ, Swartz JJ, Douglas PS, Mackey JR. Early breast cancer therapy and cardiovascular injury. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1435–1441. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Magne N, Chargari C, MacDermed D, Conforti R, Vedrine L, Spano J, Khayot D. Tomorrows targeted therapies in breast cancer patients What is the risk for increased radiation-induced cardiac toxicity? Critical Rev Oncol/Hematol. 2010;76:186–195. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chagari C, Kirov KM, Bollet MA, Magne N, Vedrine L, Cremades S, et al. Cardiac toxicity in breast cancer patients from a fractional point of view to a global assessment. Cancer Treat Rev. 2011;37:321–330. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khakoo AY, Yeh ET. Therapy insight management of cardiovascular disease in patients with cancer and cardiac complications of cancer therapy. Nature Clinical Practice Oncology. 2008;5:655–667. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin M, Esteva FJ, Alba E. Minimizing cardiotoxicity while optimizing treatment efficacy with trastuzumab review and expert recommendations. The Oncologist. 2009;14:1–11. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perez EA, Suman VJ, Davidson NE. Cardiac safety analysis of doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel with or without trastuzumab in the North Central Cancer Treatment Group N9831 adjuvant breast cancer trial. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1231–1238. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.5467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ewer MS, Ewer SM. Cardio-toxicity of anticancer treatments what the cardiologist needs to know. Nature Rev. 2010;7:564–575. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2010.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verma S, Ewer MS. (2010). Is cardio-toxicity being adequately assessed in current trials of cytotoxic and targeted agents in breast cancer? Ann Oncol . doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peairs KS, Barone BB, Snyder CF, Yeh H, Stein KB, Derr RL, et al. Diabetes mellitus and breast cancer outcomes: systematic review and meta-analyses. J Clin Oncol. 2010;29:40–46. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.3011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Erickson K, Patterson RE, Flatt SW, Natarajan L, Parker BA, Heath DD, et al. Clinically defined Type 2 diabetes mellitus and prognosis in early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;29:54–60. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.3183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lipscombe LL, Goodwin PJ, Zinman B, McLaughlin JR, Hux JE. The impact of diabetes on survival following breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;109:389–395. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9654-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harlan LC, Klabunde CN, Ambs AH, Gibson T, Bernstein L, et al. Co-morbidities, therapy and newly diagnosed conditions for women with early stage breast cancer. J Cancr Surv. 2009;3:89–98. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0084-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Senkus E, Jassem J. Cardiovascular effects of systemic cancer treatment. Cancer Treat Rev. 2011;37:300–311. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Braithwaite D, Tammemagi CM, Moore DH, Ozanne EM, Hiatt RA, Belkora J, et al. Hypertension is an independent predictor of survival disparity between African American and white breast cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:1213–1219. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harbeck N, Ewer MS, DeLaurentiis M, Suter TM, Ewer SM. Cardiovascular complications of conventional and targeted adjuvant breast cancer therapy. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:1250–1258. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yardley DA. Integrating bevacizumab into the treatment of patients with early stage breast cancer focus on cardiac safety. Clinical Breast Cancer. 2010;10(2 ):119–129. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2010.n.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones LW, Haylowsky M, Pituskin EN, Jendzjowsky NG, Tomczak CR, Haennel RG, Mackey JR. Cardiovascular reserve risk profile of postmenopausal women after chemo-endocrine therapy for hormone receptor-positive operable breast cancer. Oncologist. 2007;12:1156–1164. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-10-1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones LW, Haykowsky M, Peddle CJ, Joy AA, Pituskin EN, Tkachuk LM, et al. Cardiovascular risk profile of patients with HER2/neu-positive breast cancer treated with anthracycline-taxane-containing adjuvant chemotherapy and/or trastuzumab. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarker Prev. 2007;16(15 ):1026–1031. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patterson RE, Flatt SW, Saquib N, Rock CL, Cann BJ, et al. Medical co-morbidities predict mortality in women with a history of early stage breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;122:859–865. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0732-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Norris CM, Ljubsa A, Hegadoren KM. Gender as a determinant of responses to a self-screening questionnaire on anxiety and depression by patients with coronary artery disease. Gend Med. 2009;6:479–487. doi: 10.1016/j.genm.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Szekely A, Balong P, Benko E, Breuer T, Szekely J, Kertal MD, et al. Anxiety predicts mortality and morbidity after coronary artery and valve surgery-a 4 year follow-up study. Psychosomatic Med. 2007;69:625–631. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31814b8c0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.May HT, Horne BD, Carlquist JF, Sheng X, Joy E, Catinella AP. Depression after coronary artery disease is associated with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1440–1447. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Todaro JF, Shen BJ, Niaura R, Tikemeier PL. Prevalence of depressive disorders in men and women enrolled in cardiac rehabilitation. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2005;25:71–75. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200503000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sperus JA, McDonnell M, Woodman CL, Fihn SD. Association between depression and worse disease specific functional status in outpatients with coronary artery disease. Am Heart J. 2000;140:105–110. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2000.106600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Institute of Medicine. Meeting psychosocial needs of women with breast cancer. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Albini A, Pennesi G, Donatelli F, Cammarota R, De Flora S, Noonan DM. Cardio-toxicity of anticancer drugs The need for cardio-oncology and cardio-oncological prevention . J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:14–25. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Giordano SH, Hortobagyoi G. Local recurrence or cardiovascular disease pay now or later. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:340–341. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lenihan DJ, Esteva FJ. Multidisciplinary strategy for managing cardiovascular risk when treating patients with early stage breast cancer. The Oncologist. 2008;13:1224–1234. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ewer MS, Ewer SM. Long-term cardiac safety of dose-dense anthracycline therapy cannot be predicted from early ejection fraction data. J Clin Oncol. 2009 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.5091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Institute of Medicine. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cappiello M, Cunningham R, Knobf MT, Erdos D. Breast cancer survivors. Information and support after treatment. Clin Nurs Res. 2007;16:278–293. doi: 10.1177/1054773807306553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bower JE, Ganz PA, Desmond KA, et al. Fatigue in breast cancer survivors occurrence correlates and impact on quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:743–753. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.4.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gaillard S, Stearns V. Aromatase inhibitor-associated bone and musculoskeletal effects new evidence defining etiology and strategies for management. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:205–214. doi: 10.1186/bcr2818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Berger AM. Update on the State of the Science Sleep-wake disturbances in adult patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2009;36:e165–e177. doi: 10.1188/09.ONF.E165-E177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Knobf MT. Symptom distress before during and after adjuvant breast cancer therapy. Developments Support Care. 2000;4:13–17. [Google Scholar]

- 53.vanWeert E, Hoekstra-Weebers J, Otter R, Postema K, Sanderman R, van der Schans C. Cancer-related fatigue predictors and effects of rehabilitation. Oncologist. 2006;11:184–196. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.11-2-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Avis NA, Crawford S, Manuel J. Quality of life among younger women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3322–3330. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bakitas M. Background noise The experience of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Nur Res. 2007;56:323–331. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000289503.22414.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reid-Arndt SA, Hsieh C, Perry MC. Neuropsychological functioning and quality of life during the first year after completing chemotherapy for breast cancer. Psycho-oncol. 2010;19:535–544. doi: 10.1002/pon.1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Knobf M, Mullen J, Xistris D, Moritz D. Weight gain in women with breast cancer on adjuvant chemotherapy. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1983;10:28–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Knobf MT. Psychosocial responses in breast cancer survivors. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2007;23:71–83. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Knobf MT. Carrying on The experience of premature menopause in women with early stage breast cancer. Nurs Res. 2002;51:9–17. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200201000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Irwin M, Crumley D, McTiernan A, et al. Physical activity levels before and after a diagnosis of breast cancer. Cancer. 2003;97:1746–1757. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Irwin M, McTiernan A, Baumgarten RN, et al. Changes in body fat and weight after a breast cancer diagnosis influence of demographic prognostic and lifestyle factors. J Clin Oncol . 2005;23:774–782. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McInnes J, Knobf MT. Weight gain and quality of life in women treated with adjuvant therapy for breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2001;28:675–684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kroenke CH, Chen WY, Rosner B, Holmes MD. (2005). Weight, weight gain and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol . 2005;23:1370–1378. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kutynec CL, McCargar L, Barr SI, Hislop TG. Energy balance in women with breast cancer during adjuvant treatment. J Amer Diet Assoc. 1999;99:1222–1227. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(99)00301-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ingram C, Brown J. Patterns of weight and body composition change in premenopausal women with early stage breast cancer. Canc Nurs. 2004;27:483–490. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200411000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cheney CL, Mahloch J, Freeny P. Computerized tomography assessment of women with weight changes associated with adjuvant treatment for breast cancer. Am Jour Clin Nutrition. 1997;66:141–146. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/66.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Knobf MT, Insogna K, DiPietro L, Fennie K, Thompson AS. An aerobic weight-loaded pilot exercise intervention for breast cancer survivors bone remodeling and body composition outcomes. Biol Res Nurs. 2008;10:34–43. doi: 10.1177/1099800408320579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Knobf MT. Psychological and physical distress associated with adjuvant chemotherapy in women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1986;14:678–684. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1986.4.5.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rock CL, Flatt SW, Newman V, et al. Factors associated with weight gain in women after diagnosis of breast cancer. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99:1212-1218– 1221. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(99)00298-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Makari-Judson G, Judson CH, Mertens WC. Longitudinal patterns of weight gain after breast cancer diagnosis observations beyond the first year. The Breast Journal. 2007;13:258–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2007.00419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Thomson C, Thompson PA, Wright-Bea J, Nardi E, Frey GR, Stopeck A. (2009). Metabolic syndrome and elevated c-reactive protein in breast cancer survivors on adjuvant hormone therapy. J Women's Health. 2009;18:2041–2047. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chen TH, Gona P, Sutherland PA, Benjamin ES, Wilson PW, Larson MG, Vasan RS, Robins SJ. Long-term c-reactive protein variability and prediction of metabolic risk. Am Jour Med. 2009;122:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hamer M, Chida Y, Stamatakis E. Association of very highly elevated c-reactive protein concentration with cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality. Clinical Chemistry. 2010;56:132–135. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2009.130740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wolin KY, Carson K, Colditz GA. Obesity and cancer. Oncologist. 2010;15:556–565. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bittner V. Menopause age and cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:2374–2375. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Matthews KA, Crawford SL, Chae CU, Everson-Rose SA, Sowers MF, Sternfeld B, Sutton-Tyrell K. Are changes in cardiovascular disease risk factors in midlife women due to chronological aging or to the menopause transition? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:2366–2373. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ewer MS, Gluck S. A woman's heart The impact of adjuvant endocrine therapy on cardiovascular health. Cancer. 2009;115:1813–1826. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Saarto T, Blomqvist C, Ehnholm C, Taskinen M, Elomaa I. Effects of chemotherapy-induced castration on serum lipids and apoproteins in premenopausal women with node-positive breast cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:4453–4457. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.12.8954058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Russell R. Anthracyclines and cardiotoxicity. Current Cardiology Reviews. 2011;7(4 ):214–220. doi: 10.2174/157340311799960645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hedhli N, Russell K. Cardiotoxicity of molecularly targeted agents. Current Cardiology Reviews. 2011;7(4 ):221–233. doi: 10.2174/157340311799960636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chien KR. Herceptin and the heart A molecular modifier of cardiac failure. N Engl J Med. 2006;358(8 ):789–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Peng X, Pentassuglia L, Sawyer DB. Emerging anticancer therapeutic targets and the cardiovascular system is there cause for concern? Circ Res. 2010;106:35–46. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.211276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zambelli A, DellaPorta MG, Eleuteri E, DeGiuki L, Catalano O, Tondini C, Riccardi A. Predicting and preventing cardiotoxicity in the era of breast cancer targeted therapies. Novel molecular tools for clinical trials. The Breast . 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jurcut R, Wildiers H, Ganame J, D'hooge J, Paridaems R, Voight J. Detection and monitoring of cardiotoxicity-what does modern cardiology offer? Support Care Cancer. 2008;16:437–445. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0397-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yoon GJ, Telli ML, Kao DP, Matsudo KY, Carlson RW, Wittcles RM. Left ventricular dysfunction in patients receiving carditoxic cancer therapies. J Am Coll Cardiol . 2010;56:1644–1650. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Granger CB. Prediction and prevention of chemotherapy-induced cardiomyopathy. Can it be done? Circulation . 2006;114:2432–2433. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.666248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Eyre H, Kahn R, Robertson R. Preventing cancer cardiovascular disease and diabetes A common agenda for the American Cancer Society the American Diabetes Association and the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2004;109:3244–3255. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133321.00456.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kushi LH, Byers T, Doyle C, Bandera EV, McCoullough M, Gansler T, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines on nutrition and physical activity for cancer prevention: reducing the risk of cancer with healthy food choices and physical activity. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:254–281. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.5.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kokkmos PF, Narayan P, Papademetriou V. Exercise as hypertension therapy. Cardiol Clin. 2001;19:507–516. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8651(05)70232-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chipkin SR, Klugh SA, Chasan-Taber L. Exercise and diabetes. Cardiol Clin. 2001;19:489–505. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8651(05)70231-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dunn AL. Effectiveness of lifestyle physical activity interventions to reduce cardiovascular disease. Amer J Lifestyle Med. 2009;3(suppl1 ):11s–18s. doi: 10.1177/1559827609336067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Camethon MR. Physical activity and cardiovascular disease. How much is enough? Amer J Lifestyle Med. 2009;3(suppl1 ):44s–49s. doi: 10.1177/1559827609332737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bosworth HB, Powers BJ, Oddone EZ. Patient self-management support: novel strategies in hypertension and heart disease. Cardiol Clin. 2010;28:655–663. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Holmes MD, Chen WY, Feskanich D, Kroenke CH, Colditz GA. Physical activity and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. JAMA. 2005;293:2479–2486. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.20.2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Holick CN, Newcomb PA, Trentham-Dietz A, Titus-Ernstoff L, Bersch A, Stampfer MJ, et al. Physical activity and survival after diagnosis invasive breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:379–386. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Irwin ML, Smith AW, McTiernan A, Ballard-Barbash R, Cronin K, Gilliland FD, et al. Influence of pre- and postdiagnosis physical activity on mortality in breast cancer survivors the Health Eating Activity and Lifestyle study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3958–3964. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.9822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sternfeld B, Weltzien E, Quesenberry CP, Castillo AL, Kwan M, Slattery ML, Caan BJ. Physical activity and risk of recurrence and mortality in breast cancer survivors findings from the LACE study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:87–95. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bertram LA, Stefanik ML, Saquib N, Natarajan L, Patterson RE, Bardwell W, et al. Physical activity additional breast cancer events and mortality among early-stage breast cancer survivors findings from the WHEL study. Cancer Causes Control. 2011;22:427–435. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9714-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Irwin ML, McTiernan A, Manson JE, Thomson CA, Sternfeld B, Stefanik ML, et al. Physical activity and survival in postmenopausal women with breast cancer results from the Women's Health Initiative. Cancer Prev Res. 2011;4:522–529. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Speck RM, Courneya KS, Masse L, Duval S, Schmidtz KH. An update of controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:87–100. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kim C, Kang D, Park J. A meta-analysis of aerobic exercise interventions for women with breast cancer. West J Nurs Res. 2009;31:437–461. doi: 10.1177/0193945908328473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.deBacker IC, Schep G, Backs FJ, Vreugdenhil G, Kulpers H. Resistance training in cancer survivors a systematic review. Int J Sports Med. 2009;30:703–712. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1225330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mares M, Brockow T. Cochrane Collection. John Wiley & Sons ; 2009 . Exercise for women receiving adjuvant therapy for breast cancer (review) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ferrer RA, Huedo-Medina TB, Johnosn BT, Ryan S, Pescatello LS. Exercise interventions for cancer survivors a meta-analysis of quality of life outcomes. Ann Behav Med. 2011;41:32–47. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9225-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Schmitz KH, Holtzman J, Courneya K, et al. Controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:1588–1595. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ingram C, Visovsky C. Exercise intervention to modify physiologic risk factors in cancer survivors. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2007;23:275–284. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Knobf MT, Musanti R, Dorward J. Exercise and quality of life outcomes in patients with cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2007;23:285–296. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.White SM, McAuley E, Estabrooks PA, Courneya KS. Translating physical activity interventions for breast cancer survivors into practice an evaluation of randomized controlled trials. Ann Behav Med. 2009;37:10–19. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9084-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Al-Majid S, Gray DP. A biobehavioral model for the study of exercise interventions in cancer-related fatigue. Biol Res Nurs. 2008;10:381–391. doi: 10.1177/1099800408324431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Jones LW, Liang Y, Pituskin EN, Battaglini CL, Scott JM, Hornsby WE, Haykowsky M. Effect of exercise training on peak oxygen consumption in patients with cancer a meta-analysis. Oncologist. 2011;16:112–120. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ewertz M, Jensen M, Gunnarsdottir KA, Hojiris I, Jakobsen EH, Nielsen D, et al. Effect of obesity on prognosis after early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;29:25–31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.7614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Chen X, Lu W, Zheng W, Gu K, Chen Z, Zheng Y, Shu X. Obesity and weight change in relation to breast cancer survival. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;122:823–833. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0708-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Cheema BS, Gaul CA. Full-body exercise training improves fitness and quality of life in survivors of breast cancer. J Strength Conditioning Rses. 2006;20:14–21. doi: 10.1519/R-17335.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Goodwin P, Explen MJ, Butler K, Winocur J, Pritchard K, Brazel S, et al. Multidisciplinary weight management in locoregional breast cancer results of a phase II study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1998;48:53–64. doi: 10.1023/a:1005942017626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.McTiernan A, Ulrich C, Kumai C, Bean D, Schwartz R, Mahloch J, et al. Anthropometrical and hormone effects of an eight week exercise-diet intervention in breast cancer patients: results of a pilot study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7:477–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Mefford K, Nichols JF, Pakiz B, Rock CL. A cognitive behavioral therapy intervention to promote weight loss improves body composition and blood lipid profiles among overweight breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006 doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9410-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Demark-Wahnefried W, Case LD, Blackwell K, Marcom PK, Kraus W, Aziz N, et al. Results of a diet/exercise feasibility trial to prevent adverse body composition changes in breast cancer patients on adjuvant chemotherapy. Clinical Breast Cancer. 2008;8:70–79. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2008.n.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Muraca L, Leung D, Clark A, Beduz MA, Goodwin P. Breast cancer survivors taking charge of lifestyle choices after treatment. European J Oncol Nurs. 2011;15:250–253. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ballard-Bash R, Hunsberger S, Alciati MH, Blair SN, Goodwin P, McTiernan A, Wing R, Schatzkin A. Physical activity weight control and breast cancer risk and survival clinical trial rationale and design considerations. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:630–643. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Khakoo AY, Liu PP, Force T, Lopez-Berestein G, Jones LW, Schneider J, Hill J. Cardiotoxicity due to cancer therapy. Texas Heart Institute Journal. 2011;38:253–256. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Schmitz KH, Courneya KS, Matthews C, Demark-Wahnefried W, Galvao DA, Pinto BM, et al. American College of Sports Medicine Roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med Science Sports Exercise . 2010 doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e0c112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Report. US Department Health Human Services: Washington DC; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Dent SF, Gaspo R, Kissner M, Pritchard KI. Aromatase inhibitor therapy toxicities and management strategies in the treatment of postmenopausal women with hormone-sensitive early breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;126:295–310. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1351-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Stricker C, Drake D, Hoyer K, Mock V. Evidence based practice for fatigue management in adults with cancer exercise as an intervention. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2004;31:963–974. doi: 10.1188/04.ONF.963-976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Jones LW, Eves ND, Haykowsky M, Joy AA, Douglas PS. Cardio-respiratory exercise testing in clinical oncology research systematic review and practice recommendations. Lancet Oncology. 2008;9:757–765. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70195-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]