Abstract

Antibody effector functions have been shown to be influenced by the structure of the Fc N-glycans. Here we studied the changes in plasma or serum IgG Fc N-glycosylation upon vaccination of 10 Caucasian adults and 10 African children. Serum/plasma IgG was purified by affinity chromatography prior to and at two time points after vaccination. Fc N-glycosylation profiles of individual IgG subclasses were determined for both total IgG and affinity-purified anti-vaccine IgG using a recently developed fast nanoliquid chromatography-electrospray ionization MS (LC-ESI-MS) method. While vaccination had no effect on the glycosylation of total IgG, anti-vaccine IgG showed increased levels of galactosylation and sialylation upon active immunization. Interestingly, the number of sialic acids per galactose increased during the vaccination time course, suggesting a distinct regulation of galactosylation and sialylation. In addition we observed a decrease in the level of IgG1 bisecting N-acetylglucosamine whereas no significant changes were observed for the level of fucosylation. Our data indicate that dependent on the vaccination time point the infectious agent will encounter IgGs with different glycosylation profiles, which are expected to influence the antibody effector functions relevant in immunity.

Millions of individuals are vaccinated worldwide each year to stimulate the adaptive immune system to produce protective antibodies as well as T-cell responses against a variety of pathogens. Vaccination with attenuated microbe strains and purified proteins results in lymphocyte sensitization, cytokine release, and the production of immunoglobulins (Igs)1 which may provide long-term immunity.

The most abundant Ig class in the humoral immune response is IgG being present at concentrations of ∼10 mg/ml in plasma and serum (1, 2). IgGs are glycoproteins, and their glycosylation is known to modulate antibody activity and effector mechanisms (3–7). Four different IgG subclasses are present in humans (IgG1–4). IgGs consist of two heavy and two light chains. The two light chains together with the N-terminal domains (VH and CH1) of the two heavy chains form the fragment antigen binding (Fab) moiety, whereas the fragment crystallizable (Fc) moiety is formed by the C-terminal domains (CH2 and CH3) of the two heavy chains. A single biantennary, often core fucosylated N-glycan is attached to the asparagine residue at position 297 in the CH2 domain of the heavy chains. These N-glycans vary in the number of antenna galactoses and may carry a sialic acid on one of the antennae. Part of the N-glycans contain a bisecting N-acetylglucosamine (bisecting GlcNAc) (8).

Recently, some B-cell stimuli have been identified, which resulted in changes in antibody glycosylation and indicated a pronounced short-term regulation of IgG glycosylation in humans (9). In vitro stimulation of B cells with the environmental factor all-trans retinoic acid resulted in the expression of IgG1 with decreased galactosylation within a time-range of several days, whereas increased galactosylation and reduced bisecting GlcNAc have been observed after stimulation with CpG oligodeoxynucleotide (stimulates the innate immune system) or interleukin 21 (stimulates the adaptive immune system) (9).

Hitherto, induction of specific glycosylation patterns of IgGs upon immunization has only been shown in animal experiments (4, 10, 11). Specific pathogen free CBA/Ca mice immunized with bovine serum albumin (BSA) in incomplete Freund's adjuvant showed an initial decrease in galactose content on anti-BSA IgG with increasing antibody titer which partly returned to original levels when titers fell (10). In a murine nephrotoxic serum nephritis model, total IgG sialylation has been shown to reduce drastically in mice pre-sensitized with sheep IgG and challenged with sheep anti-mouse glomerular basement membrane preparation compared with unimmunized controls (4). This suggests that the sialylation change may provide a switch from innate anti-inflammatory activity in the steady state to an adaptive pro-inflammatory response. Repeated immunization of male ICR mice with ovalbumin in physiological saline resulted in an increase of the fucose content on anti-ovalbumin IgG, whereas mannosylation, galactosylation, and sialylation were unaffected (11). These animal studies demonstrate that upon immunological challenge glycosylation of the produced antibodies differ.

Measurement of IgG glycosylation at the glycopeptide level ensures specificity as it allows the assignment of glycan structures to the Fc portions of individual IgG subclasses, which is important because Fc glycosylation and Fab glycosylation appear to have very distinct functions (12). Because of the high sensitivity of the mass spectrometric detection it is possible to set up affinity-based microtitration well plate IgG capturing and purification assays as modifications of (commercially available) ELISAs and combine them successfully with IgG glycosylation profiling of glycopeptides (13). This allows glycan profiling at the level of antigen-specific IgG. Interestingly, antigen-specific IgGs have repeatedly been shown to be glycosylated in a very distinct manner that differs considerably from the pool of total IgG (13–16).

Here, we describe IgG glycosylation changes induced by vaccination in humans. We analyzed the Fc glycosylation of IgG1 induced by vaccination against Mexican flu (Caucasian adults), seasonal flu (African children), and tetanus (African children). Consistently we observe a transient increase of both galactosylation and sialylation, together with a decrease of the incidence of bisecting GlcNAc. This glycosylation time course is specifically observed for the vaccine-induced IgG1 whereas the glycosylation of total IgG1 is unaffected. On the basis of the known association of IgG glycosylation features with antibody efficacy in in vitro assays and animal models (4–6, 17–20), we expect that the specific IgG1 glycosylation features observed upon vaccination will influence antibody effector functions.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Study Cohort

The study cohort is described in Table I. From 10 healthy Caucasians who were vaccinated twice (at day 0 and at day 21) with MF59-adjuvanted 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) (Focetria 2009, Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics, Rosia, Italy), serum was obtained at day 0 (just before vaccination), day 21 (just before the second dose) and day 56 (21). This study was approved by the ethics committee of Leiden University Medical Center (protocol number 09.187). Subjects provided written informed consent for participation in the study and for the use of stored serum samples for the purpose of this study (21).

Table I. Human sample cohort.

| Group | Sex | Counts | Vaccination | Age (years) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Youngest | Oldest | Mean | STD | ||||

| Caucasian | Female | 7 | Influenza (Focetria) | 33 | 58 | 45.7 | 9.9 |

| Male | 3 | Influenza (Focetria) | 26 | 59 | 40.7 | 16.8 | |

| African | Female | 6 | Influenza (Begrivac) | 7 | 11 | 8.8 | 1.6 |

| Male | 4 | Influenza (Begrivac) | 8 | 10 | 9.0 | 0.8 | |

| African | Female | 4 | Tetanus | 7 | 11 | 9.3 | 1.71 |

| Male | 2 | Tetanus | 9 | 10 | 9.5 | 0.71 | |

From 10 Gabonese children heparin plasma was obtained prior to vaccination (day 0) and at day 14 and 28 after vaccination with Begrivac 2004/2005 (Chiron Behring GmbH, Marburg, Germany) (22). Simultaneously with the influenza vaccination, the African children were vaccinated with a tetanus toxoid booster (NIPHE, Bilthoven, The Netherlands). For six of the ten children enough material was available to additionally evaluate tetanus specific IgG Fc N-glycosylation changes. Three girls and all boys were tested positive for helminth infection and one girl was tested positive for malaria. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the International Foundation of the Albert Schweitzer Hospital in Lambaréné. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardians of each child prior to participation in the study (22).

Preparation of Antigen Specific Affinity Beads

For the preparation of antigen specific beads pooled vaccine doses of Focetria (20 doses), Begrivac 2004/2005 (4 doses) and tetanus toxoid (10 doses) were buffered 4:1 (v:v) with 0.2 m sodium bicarbonate (Fluka, Steinheim, Germany) containing 0.5 m sodium chloride (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). NHS-activated Sepharose 4 Fast Flow beads (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) were washed 3 times with 10 volumes of ice-cold 1 mm hydrochloric acid (HCl; Merck), and to 200–400 μl of the beads buffered Focetria, Begrivac, or tetanus toxoid was applied. The antigens were immobilized overnight at 4 °C under continuous shaking followed by a 4 h blocking of residual NHS groups at RT with 0.1 m tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (Tris; Roche Diagnostics, Manheim, Germany) brought to pH 8.5 with HCl (Merck). Beads were washed 3 times with alternating pH using 0.1 m glacial acetic acid (Merck) with 0.5 m sodium chloride (pH 4–5) and Tris-HCl (pH 8.5) and stored in 0.1 m Tris-HCl (pH 8.5) with 20% ethanol at 4 °C until usage.

IgG Glycosylation Analysis

Human polyclonal IgGs (IgG1, 2 and 4) were captured from 2 μl plasma or serum by affinity chromatography with Protein A-SepharoseTM Fast Flow beads (GE Healthcare) in 96-well plates as described previously (23). Vaccine specific IgGs were purified from 20 μl human plasma or serum by incubation with 3–5 μl of the immobilized tetanus toxoid or influenza antigen beads in 96-well filter plates for one hour. Captured antibodies were washed with 3 × 200 μl phosphate-buffered saline, 3 × 200 μl water, eluted with 100 μl of 100 mm formic acid (Fluka) and dried by vacuum centrifugation. Purified IgGs (total and vaccine-directed) were dissolved in 20 μl of 50 mm ammonium bicarbonate buffer (Fluka), and shaken for 10 min. To minimize potential autolysis and missed cleavages, lyophilized sequencing grade modified trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI) was dissolved in ice-cold 1 mm acetic acid (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), and immediately 20 μl was added to the IgG samples. Samples were shaken for 1 min, checked for the correct pH (>6) and incubated overnight at 37 °C. The digests were centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 5 min and aliquots (250 nl for total IgG, 5000 nl for vaccine specific IgG) were analyzed by fast nanoLC-ESI-MS (24) on a Ultimate 3000 HPLC system (Dionex Corporation, Sunnyvale, CA) equipped with a Dionex Acclaim PepMap100 C18 (5 μm particle size, 5 mm x 300 μm i.d.) trap column and an Ascentis Express C18 nano column (2.7 μm HALO fused core particles, 50 mm x 75 μm i.d.; Supelco, Bellefonte, USA), which were coupled to a micrOTOF-Q mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) by a sheath-flow-ESI sprayer (capillary electrophoresis ESI-MS sprayer; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) (24). Scan spectra were recorded from 300 to 2000 dalton with 2 average scans at a frequency of 1 Hz. The Ultimate 3000 HPLC system and the Bruker micrOTOF-Q were respectively operated by Chromeleon Client version 6.8 and micrOTOF control version 2.3 software.

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry datasets were internally calibrated using a list of known glycopeptides and exported to the open mzXML using Bruker DataAnalysis 4.0 in batch mode. Data processing was performed with the in-house developed software msalign2 (25), a simple warping script in AWK (26), “Xtractor2D” and Microsoft Excel. The software and ancillary scripts are freely available at www.ms-utils.org/Xtractor2D.

Relative intensities of 46 glycopeptide species (Table II) derived from IgG1 (18 glycoforms), IgG4 (10 glycoforms), and IgG2 (18 glycoforms) were obtained by integrating and summing three isotopic peaks followed by normalization to the total subclass specific glycopeptide intensities. On the basis of the normalized intensities for the various IgG Fc N-glycoforms the level of galactosylation, sialylation, bisecting N-acetylglucosamine and fucosylation was calculated. The level of galactosylation was calculated according to the formula (G1F + G1FN + G1FS + G1FNS + G1 + G1N + G1S) * 0.5 + G2F + G2FN + G2FS + G2FNS + G2 + G2N + G2S for the IgG1 and IgG2 subclasses and (G1F + G1FN + G1FS + G1FNS) * 0.5 + G2F + G2FN + G2FS + G2FNS for the IgG4 subclass. The prevalence of IgG sialylation was determined by summation of all sialylated Fc N-glycopeptide species (G1FS, G2FS, G1FNS, G2FNS, G1S and G2S for IgG1 and IgG2, and G1FS, G2FS, G1FNS and G2FNS for IgG4). The number of sialic acid moieties present on the galactose moieties (SA/Gal) is calculated by dividing the prevalence of IgG sialylation by 2 * the level of galactosylation. The incidence of bisecting N-acetylglucosamine is obtained by summing all bisected Fc N-glycopeptide species (G0FN, G1FN, G2FN, G1FNS, G2FNS, G0N, G1N and G2N for the IgG1 and IgG2 subclass or G0FN, G1FN, G2FN, G1FNS and G2FNS for the IgG4 subclass). The percentage of IgG1 and IgG2 fucosylation was determined by summing the relative intensities of all fucosylated Fc N-glycopeptide species (G0F, G1F, G2F, G0FN, G1FN, G2FN, G1FS and G2FS). For the IgG4 subclass no fucosylation level was determined as the afucosylated species remained below the limit of detection.

Table II. Glycoforms of human plasma IgG detected by nano-LC-ESI-MS.

| Glycand species | IgG1 P01857b E293EQYNSTYR301c |

IgG2 P01859b E293EQFNSTFR301c |

IgG4 P01861b E293EQFNSTYR301c |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [M+2H]2+ | [M+3H]3+ | [M+2H]2+ | [M+3H]3+ | [M+2H]2+ | [M+3H]3+ | |

| No glycan | 595.260 | 397.176 | 579.265 | 386.513 | 587.262 | 391.844 |

| G0F | 1317.527 | 878.687 | 1301.532 | 868.024 | 1309.529 | 873.356a1 |

| G1F | 1398.553 | 932.705 | 1382.558 | 922.042 | 1390.556 | 927.373a2 |

| G2F | 1479.580 | 986.722 | 1463.585 | 976.059 | 1471.582 | 981.391 |

| G0FN | 1419.067 | 946.380 | 1403.072 | 935.717 | 1411.069 | 941.049a3 |

| G1FN | 1500.093 | 1000.398 | 1484.098 | 989.735 | 1492.096 | 995.066a4 |

| G2FN | 1581.119 | 1054.416 | 1565.124 | 1043.752 | 1573.122 | 1049.084 |

| G1FS | 1544.101 | 1029.737 | 1528.106 | 1019.073 | 1536.104 | 1024.405a5 |

| G2FS | 1625.127 | 1083.754 | 1609.132 | 1073.091 | 1617.130 | 1078.423 |

| G1FNS | 1645.641 | 1097.430 | 1629.646 | 1086.766 | 1637.643 | 1092.098 |

| G2FNS | 1726.667 | 1151.447 | 1710.672 | 1140.784 | 1718.670 | 1146.116 |

| G0 | 1244.498 | 830.001 | 1228.503 | 819.338 | - | - |

| G1 | 1325.524 | 884.019 | 1309.529 | 873.356a1 | - | - |

| G2 | 1406.551 | 938.036 | 1390.556 | 927.373a2 | - | - |

| G0N | 1346.038 | 897.694 | 1330.043 | 887.031 | - | - |

| G1N | 1427.064 | 951.712 | 1411.069 | 941.049a3 | - | - |

| G2N | 1508.090 | 1005.730 | 1492.096 | 995.066a4 | - | - |

| G1S | 1471.072 | 981.051 | 1455.077 | 970.387 | - | - |

| G2S | 1552.098 | 1035.068 | 1536.104 | 1024.405a5 | - | - |

a1–a5 Isomeric glycopeptide species of IgG4 and IgG2.

b SwissProt entry number.

c Tryptic IgG glycopeptide sequence.

d Glycan structural features are given in terms of number of galactoses (G0, G1, G2), fucose (F), bisecting N-acetylglucosamine (N), and N-acetylneuraminic acid (S).

Statistical Analysis

Differences between the 3 vaccination time points were evaluated using the Friedman test. Uncorrected p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. In depth analyses of the differences between protein A (total IgG1) and vaccine specific purified IgG1 were performed with the Wilcoxon Signed Rank test. p-Values were adjusted for multiple comparisons by Bonferroni correction, and p values < 0.013 were considered statistically significant. Data evaluation and statistical analyses were performed with Microsoft Excel and SPSS 16.0, respectively.

RESULTS

To evaluate IgG Fc N-glycosylation changes upon vaccination tryptic IgG glycopeptides prepared from human plasma or serum were analyzed using a recently established fast nanoLC-ESI-MS method (24). An optimized tryptic cleavage procedure was applied (23), and no tryptic missed cleavages were observed. On the basis of literature knowledge of IgG N-glycosylation (27–31) the nanoliquid chromatography-electrospray ionization (LC-ESI-MS) method allowed unambiguous assignment of 46 IgG glycopeptides species (18 glycoforms of IgG1, 10 of IgG4, and 18 of IgG2; Table II). Glycoforms having 5 N-acetylhexosamine residues were interpreted as bisected species (27–31). In agreement with literature data, N-acetylneuraminic acid was the only form of sialic acids observed in our analysis (27–31). The fast nanoHPLC separation together with the integration and summation of multiple isotopic peaks for each assigned IgG Fc N-glycopeptide species provides subclass specific glycosylation information with good precision (24).

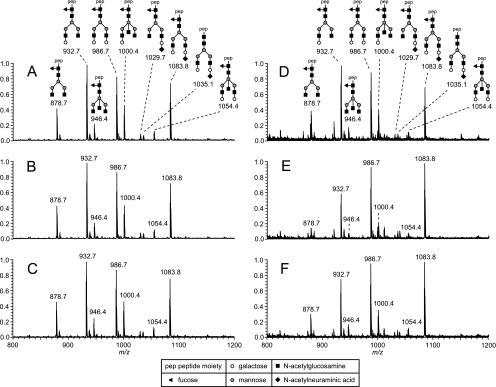

Fc N-glycosylation profiles of total IgG and antigen affinity captured IgG were evaluated for 10 Caucasian adults and 10 African children prior to vaccination and at several time points after vaccination. For each individual similar total IgG1 Fc N-glycopeptide profiles were observed at all vaccination time points (typical example Figs. 1A–1C; supplemental Fig. S1A–1C). By contrast, antigen affinity-purified IgG1 showed changes in Fc N-glycopeptide profiles with time (typical example Figs. 1D–1F; supplemental Fig. S1D–1I). Higher intensities for galactosylated glycoforms were observed for Caucasian adults at day 21 and 56 of influenza vaccination as compared with day 0 (Figs. 1E–1F). Similarly, in African children galactosylated glycoforms for influenza- and tetanus affinity-purified IgG1 were higher at day 14 and 28 than before vaccination (supplemental Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

Nano-RPLC-ESI-MS profiles (sum spectra of 1 min) of tryptic IgG1 glycopeptides purified from plasma of an Caucasian adult by protein A (A–C) and influenza vaccine (D–F) affinity chromatography prior to vaccination (A and D), and at day 21 (B and E) and 56 (C and F) after vaccination.

Only very low signals were obtained for IgG4 and IgG2 Fc N-glycopeptides in vaccine affinity purified samples, and no changes of these profiles were observed with time. We, therefore, excluded IgG4 and IgG2 glycosylation from further analysis. In the following, the vaccination-associated changes in IgG1 fucosylation, galactosylation, sialylation, and the incidence of bisecting GlcNAc are described.

Fucosylation

Differences between total and antigen affinity-purified IgG1 were evaluated using the Wilcoxon Signed Rank test. Only the day 0 time point of Begrivac affinity-purified IgG1 of African children showed a significantly lower fucosylation compared with total IgG1 (p value = 0.007; Supporting Table I, medians available in Table IV).

Table IV. Friedman test for the IgG1 glycosylation features of African children. *Friedman test p values < 0.013 are considered to be significant and are highlighted in bold.

| Glycosylation feature | Medians |

p values* |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein A |

Begrivac 04/05 |

Tetanus |

||||||||||

| Day 0 | Day 14 | Day 28 | Day 0 | Day 14 | Day 28 | Day 0 | Day 14 | Day 28 | Protein A | Begrivac | Tetanus | |

| Fucosylation | 95.1 | 94.8 | 94.8 | 94.2 | 93.8 | 93.0 | 93.1 | 94.7 | 94.7 | 0.497 | 0.741 | 0.135 |

| Bisecting N | 11.8 | 11.5 | 11.6 | 11.9 | 7.5 | 10.0 | 13.4 | 10.3 | 10.8 | 0.122 | <0.001 | 0.160 |

| Galactosylation | 47.5 | 49.0 | 48.2 | 56.0 | 74.3 | 67.9 | 51.3 | 64.7 | 62.1 | 0.027 | <0.001 | 0.006 |

| Sialylation | 15.1 | 16.1 | 15.3 | 20.1 | 30.4 | 25.9 | 16.6 | 26.5 | 24.4 | 0.122 | <0.001 | 0.060 |

| SA/Gal | 15.4 | 16.8 | 15.8 | 17.3 | 20.8 | 19.7 | 16.0 | 19.5 | 18.8 | 0.202 | <0.001 | 0.002 |

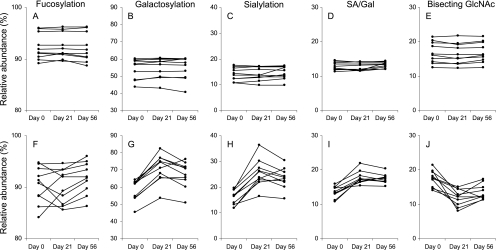

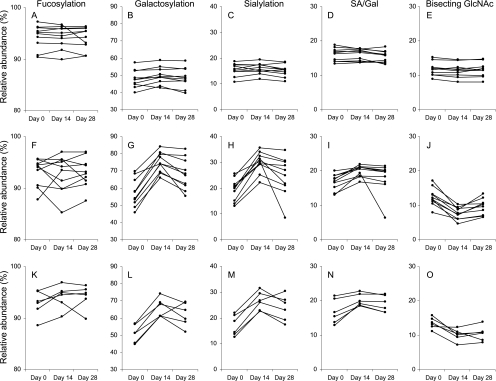

Next we looked for longitudinal changes in IgG1 Fc fucosylation by evaluating the three time points with the Friedman test. Total and antigen affinity-purified IgG1 of Caucasian adults (Figs. 2A, 2F) and African children (Figs. 3A, 3F, 3K) did not show any changes in Fc fucosylation during the influenza or tetanus vaccination time courses (Table III and IV).

Fig. 2.

Change in IgG1 glycosylation features upon influenza vaccination of Caucasian adults. For total IgG1 (A–E) and antigen (F–J) affinity-purified IgG1 the levels of fucosylation (A, F), galactosylation (B, G) sialylation (C, H), SA/Gal (D, I) and bisecting N-acetylglucosamine (E, J) are given.

Fig. 3.

Change in IgG1 glycosylation features upon influenza and tetanus vaccination of African children. For total IgG1 (A–E), and influenza (F–J) and tetanus (K–O) affinity-purified IgG1 the levels of fucosylation (A, F, K), galactosylation (B, G, L) sialylation (C, H, M), SA/Gal (D, I, N) and bisecting N-acetylglucosamine (E, J, O) are given.

Table III. Friedman test for the IgG1 glycosylation features of Caucasian adults.

| Glycosylation feature | Medians |

p values* |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein A |

Focetria 09 |

|||||||

| Day 0 | Day 21 | Day 56 | Day 0 | Day 21 | Day 56 | Protein A | Focetria 09 | |

| Fucosylation | 91.6 | 91.6 | 91.5 | 91.0 | 90.7 | 91.9 | 0.061 | 0.061 |

| Bisecting N | 16.2 | 15.8 | 16.2 | 17.6 | 12.2 | 12.5 | 0.150 | <0.001 |

| Galactosylation | 56.9 | 57.7 | 57.1 | 62.1 | 73.0 | 68.9 | 0.082 | <0.001 |

| Sialylation | 14.0 | 13.6 | 14.7 | 16.7 | 24.9 | 23.6 | 0.905 | <0.001 |

| SA/Gal | 12.6 | 12.6 | 13.4 | 13.5 | 17.4 | 17.2 | 0.670 | <0.001 |

* Friedman test p value < 0.05 are considered to be significant and are highlighted in bold.

Galactosylation

In Caucasians and Africans the median level of galactosylation for total IgG1 at day 0 (medians available in Table III and IV) was significantly lower than for the influenza affinity purified IgG1 (p values = 0.005; supplemental Table S1). At the two time points after vaccination (day 21 and 56 for Caucasians, day 14 and 28 for Africans) the level of galactosylation for total IgG1 remained significantly lower compared with the corresponding time points of influenza specific purified IgG1 (p values = 0.005; supplemental Table S1). For the difference in galactosylation between total IgG1 and tetanus affinity-purified IgG1 p values of 0.028 were observed which were considered to be nonsignificant after correction for multiple testing.

The Friedman test showed changes in galactosylation upon vaccination of Caucasian adults (Figs. 2B, 2G) and African children (Figs. 3B, 3G, 3L): antigen affinity-purified IgG1 showed a significant increase in the level of Fc galactosylation (p value < 0.01; Tables III and IV) whereas no change was observed for total IgG. More specifically the level of galactosylation of influenza affinity purified IgG1 of Caucasians was significantly increased from 62.1% (median) at day 0 to 73.0% (median) at day 21 (p value = 0.005). At day 56 the level of galactosylation (median = 68.9%) remained significantly elevated compared with day 0 (p value = 0.005) and showed a tendency toward lower IgG1 galactosylation levels than at day 21 (p value = 0.047). For African children the median levels of galactosylation of influenza affinity purified IgG1 significantly increased from 56.0% at day 0 to 74.3% at day 14 (p value = 0.005) and 67.9% at day 28 (p value = 0.007). At day 28 the level of IgG1 galactosylation was significantly lower compared with day 14 (p value = 0.005).

For tetanus specific purified IgG1 the Friedman test showed a significant change in time for the level of galactosylation (p value = 0.006; Table IV). Evaluation of the specific differences between the time points with the Wilcoxon Signed Rank test showed a trend toward higher levels of galactosylation upon vaccination of the 6 children with the tetanus booster (median at day 0 = 51.3%, day 14 = 64.7% and day 28 = 62.1%; p value = 0.028). In accordance, at the level of the individual glycoforms influenza and tetanus vaccination resulted in a significant decrease of the G0F species, whereas the G2F and G2FS species were significantly increased (p values < 0.01; supplemental Tables S2 and S3).

Sialylation

At day 0 total IgG1 of African children showed a lower median level of sialylation (medians available in Table IV) than influenza affinity-purified IgG1 (p value < 0.01; supplemental Table S1). For both Africans and Caucasians the median levels of sialylation for influenza affinity-purified IgG1 at time points 2 and 3 were significantly higher compared with total IgG1 (p value < 0.01; Supporting Table I).

Influenza affinity-purified IgG1 showed a change in the level of sialylation during vaccination for Caucasian (Figs. 2C, 3H) and African (Figs. 3C, 3H, 3M) individuals (Friedman test p value < 0.001; Table III and IV). The Wilcoxon Signed Rank test revealed a significant increase in the median level of sialylation of influenza affinity purified IgG1 from 16.7% at day 0 to 24.9% at day 21 (p value = 0.005) in Caucasian adults, which remained elevated with 23.6% at day 56 (p value = 0.005). No significant difference was observed in the level of sialylation between day 28 and 56. For the African children a significant increase in the median level of sialylation of influenza affinity purified IgG1 was observed between day 0 (median = 20.1%) and day 14 (median = 30.4%; p value = 0.005), whereas day 28 (median = 25.9%) only showed a tendency toward higher levels (p value = 0.022). The level of IgG1 sialylation at day 28 was significantly decreased compared with day 14 (p value = 0.005).

For the six African children with additional tetanus boost vaccination the Friedman test showed a tendency toward changed levels of sialylation of the tetanus affinity purified IgG1 (p value = 0.06; Table IV).

Next we evaluated the number of sialic acids per galactose moiety (medians available in Table III and IV). At day 0 the number of sialic acids per galactose did not significantly differ between total IgG1 and antigen affinity purified IgG1 (influenza and tetanus) (supplemental Table S1). By contrast, at the time points after vaccination the number of SA/Gal was significantly higher for influenza affinity-purified IgG1 than for total IgG1 (p values < 0.01; Supporting Table I). No significant difference in the number of SA/Gal was reached for the corresponding time points of total IgG1 and tetanus affinity-purified IgG1.

Changes in the number of SA/Gal during the vaccination time course were evaluated with the Friedman test. Upon vaccination more sialic acid moieties were found per galactose independent of the ethnicity (Figs. 2D, 2I, Figs. 3D, 3I, 3N, Table III and Table IV). In depth analysis of the data for Caucasions adults with the Wilcoxon Signed Rank test showed increased ratios at days 28 and 56 as compared with day 0 (p value = 0.005). For influenza affinity purified IgG1 of African children this increase was significant between day 0 and day 14 (p value = 0.005), but not between day 0 and day 28.

Likewise, for the six African children additionally vaccinated against tetanus Friedman's test indicated that there was a significant change in the amount of sialic acids per galactose (Table IV). However, significance was not reached for the comparison of the different time points with the Wilcoxon Signed Rank test.

Incidence of Bisecting N-acetylglucosamine

Finally we evaluated the level of bisecting N-acetylglucosamine and compared the obtained medians of total IgG1 for each time point (medians available in Tables III and IV) with the corresponding time points after vaccine affinity purification. At day 0 no significant differences were observed between total IgG1 and antigen affinity-purified IgG1 (supplemental Table S1). After vaccination, influenza affinity-purified IgG1 showed a significantly lower level of bisecting N-acetylglucosamine compared with total IgG1 at the corresponding time points (p value < 0.01; Supporting Table I). By contrast, significance was not reached when we compared the corresponding time points between total IgG1 and tetanus affinity-purified IgG1.

After influenza vaccination all individuals showed a decrease in the level of bisecting N-acetylglucosamine on influenza affinity-purified IgG1 (Figs. 2E, 2J and Figs. 3E, 3J, 3O) (Friedman test p value < 0.001; Table III and IV). This decrease did not reach statistical significance for tetanus affinity-purified IgG1. The Wilcoxon Signed Rank test revealed that in Caucasian adults the median level of bisecting N-acetylglucosamine on influenza affinity purified IgG1 decreased from 17.6% at day 0 to 12.2% at day 21 (p value = 0.005). The median level at day 56 was comparable (12.5%) to the level at day 21. For the African children the level of bisecting N-acetylglucosamine on influenza affinity purified IgG1 decreased from a median of 11.9% at day 0 to 7.5% at day 14 (p value = 0.005). The level of bisecting N-acetylglucosamine at day 28 (median = 10.0%) was significantly lower than at day 0 (p value = 0.005) yet higher than at day 14 (p value = 0.005).

DISCUSSION

IgG effector mechanisms are influenced by the attached Fc N-glycans. Here we studied changes in IgG Fc N-glycosylation upon vaccination of 10 Caucasian adults and 10 African children. To our knowledge, glycosylation of the constant region of human plasma IgG1 is restricted to N-glycosylation at Asn297, and no literature reports on O-glycosylation of the constant region are available. IgG Fc N-glycosylation profiles were determined using a recently described fast nanoLC-ESI-MS method, which allows accurate registration of tryptic IgG1, IgG2 and IgG4 Fc N-glycopeptides in a single analysis (24). The relative expression levels were determined for a total of 46 IgG Fc N-glycopeptides (Table II) which were assigned unambiguously on the basis of literature knowledge of IgG N-glycosylation (27–31). From these data a set of IgG Fc N-glycosylation features, namely fucosylation, galactosylation, sialylation, sialic acids per galactose, and the level of bisecting N-acetylglucosamine were determined (24).

There were no vaccine related longitudinal changes in glycosylation of total IgG1, IgG2, and IgG4. We did detect glycosylation changes of vaccine specific IgG1 in time. Active immunization with influenza or tetanus toxoid induced higher levels of galactosylation and sialylation and decreased the bisecting GlcNAc of antigen-directed IgG1. Interestingly, we observed an increase in the number of sialic acids per galactose upon vaccination which might indicate a differential regulation of β4-galactosyltransferase and sialyltransferase activities involved in IgG Fc N-glycosylation during biosynthesis in B lymphocytes (9). We did not observe significant changes in the level of fucosylation for total IgG and antigen-directed IgG1. No further changes in the glycosylation profiles were observed upon the second immunization of the Caucasians with influenza (day 21), which was possibly because of the large time difference (35 days) between the boost vaccination and sampling.

Our results are in contrast to the results of murine immunization studies: active immunization of specific pathogen free CBA/Ca mice with BSA causes a decrease in the galactosylation level for anti-BSA IgG (10). In a murine serum nephritis model, immunization caused a drastic reduction of the IgG sialic acid content (4). Upon repeated immunization with ovalbumin, increased levels of IgG fucosylation have been observed for male ICR mice (11). Specific pathogen free mice transferred from a sterile to a conventional environment showed an initial increase in the total IgG galactose content up to day 17 after which it decreased (10). This galactosylation effect on the level of total IgG is similar to our observation of an initial galactosylation increase on vaccine specific directed IgG1. However, specific pathogen free control mice remaining in the sterile environment revealed a similar galactosylation change, suggesting that the observed effect was caused by aging of the mice rather than due to infection. Murine and human IgG subclasses/isotypes are different in various respects including their glycosylation, as murine IgG Fc N-glycans contain no bisecting GlcNAc and may carry N-glycolylneuraminic acid which is not found on human IgG (32–34). In addition, lectins expressed on murine effector cells differ from those expressed in humans (e.g. SIGN-R1 an orthologue of the human DC-SIGN) (19, 20). Furthermore, murine glycoproteins and glycoproteins including IgG expressed in murine cell lines contain Galα1,3-Gal epitopes (35–37). Hence, the study of specific glycosylation changes in murine models might not translate directly to the situation in humans.

IgG1 Fc N-glycans containing a bisecting N-acetylglucosamine have been shown to exhibit increased ADCC potency in in vitro assays (17, 18). The decrease in the level of bisecting N-acetylglucosamine on antigen-directed IgG1 upon vaccination might, therefore, suggest a lower ADCC potency of the anti-vaccine IgG1. While the high level of IgG1 Fc galactosylation found in our study is likewise expected to result in rather weak interactions with activating Fc receptors and, consequently, ADCC (4), high levels of Fc galactosylation have been found to lead to enhanced complement-dependent cytotoxicity (38, 39). Tetanus toxoid (40) and influenza envelope glycoprotein (hemagglutinin and neuraminidase) (41–43) vaccines elicit high neutralizing antibody responses which have been correlated to vaccine-induced protective immunity. Influenza vaccine induced effector functions by nonneutralizing antibodies have also been shown to be involved in influenza clearance (44–48), and these effector functions are expected to be modulated by the glycosylation changes described here. The precise effector mechanisms involved in vaccine-mediated protection are far from clear and different mechanisms might apply for different viruses under different conditions (49).

B lymphocytes may produce IgGs with distinct Fc N-glycosylation profiles as is exemplified by the glycosylation differences between vaccine specific IgG1 and total serum/plasma IgG1. First steps toward elucidating the underlying regulatory IgG glycosylation mechanisms in B cells have recently been performed (9). The glycosylation of IgG1 produced by B lymphocytes in vitro is influenced by environmental factors (all-trans retinoic acid) and factors known to stimulate the innate (i.e. CpG oligodeoxynucleotide) or adaptive (i.e. interleukin 21) immune system (9). Interestingly, the reported short-term increase in galactosylation and decrease in bisecting GlcNAc of IgG1 in oligodeoxynucleotide or interleukin 21 stimulated B cells is in agreement with our observations during vaccination of humans. Modern vaccines such as those used in this study often contain adjuvants to enhance the immunogenicity of subunit (microbe strains and purified proteins) and DNA vaccines. Adjuvants can modify the outcome of epitope presentation to the immune system by specific TH1 versus TH2 polarization efficacy (50). The observed IgG Fc N-glycosylation changes, therefore, might be a result of a combined immune response toward the antigens and the adjuvant.

One may expect that prior to vaccination the individuals have had several encounters with cross reactive influenza strains via infections or previous vaccinations resulting in the resting state IgG glycosylation profile at day 0. Although glycosylation changes were observed within weeks after vaccination, IgG1 Fc glycosylation profiles obtained 9 months after influenza vaccination (determined for four African children, data not shown) were very similar to the profiles at day 0 and are likewise interpreted as resting state profiles.

Seasonal flu (influenza) vaccination usually precedes the encounter with the virus by weeks or months (prophylactic). Hence antibodies with high galactosylation and sialylation but with low incidence of bisecting GlcNAc are expected to be the ones involved in the defense against seasonal flu. Tetanus vaccination provides two scenarios as it is often performed directly after a wound (curative), and as preventive vaccination (prophylactic) which protects the individual 10–15 years. Our data indicate that dependent on the vaccination time point the infectious agent will encounter IgGs with different glycosylation profiles (acute, high galactosylation, high sialylation versus resting state, low galactosylation, low sialylation) which might influence the antibody effector functions relevant in immunity. Interestingly, the observed switching points in the glycosylation features follow the antibody titers (data not shown) (21, 22).

In conclusion, analysis of different populations and races shed some light on natural effects of vaccination on antibody glycosylation profiles. Obviously, glycosylation patterns observed by us upon vaccination can not be easily explained from a teleological point of view, but it should be stressed that the regulatory aspects and functional implications of human IgG glycosylation features are still largely unknown, and that further research is required.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hoffmann la Roche for financial support.

Footnotes

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1 and Tables S1 to S3.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1 and Tables S1 to S3.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- LC

- liquid chromatography

- ESI

- electrospray ionization

- MS

- mass spectrometry

- Fc

- fragment crystallizable

- Ig

- immunoglobulin

- Fab

- fragment antigen binding

- GlcNAc

- bisecting N-acetylglucosamine

- SA/Gal

- sialic acid per galactose

- BSA

- bovine serum albumin

- ELISA

- enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- Tris

- tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane

- HCl

- hydrochloric acid

- ADCC

- antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity

- CDC

- complement-dependent cytotoxicity.

REFERENCES

- 1. Plebani A., Ugazio A. G., Avanzini M. A., Massimi P., Zonta L., Monafo V., Burgio G. R. (1989) Serum IgG subclass concentrations in healthy subjects at different age: age normal percentile charts. Eur. J. Pediatr. 149, 164–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Butler M., Quelhas D., Critchley A. J., Carchon H., Hebestreit H. F., Hibbert R. G., Vilarinho L., Teles E., Matthijs G., Schollen E., Argibay P., Harvey D. J., Dwek R. A., Jaeken J., Rudd P. M. (2003) Detailed glycan analysis of serum glycoproteins of patients with congenital disorders of glycosylation indicates the specific defective glycan processing step and provides an insight into pathogenesis. Glycobiology 13, 601–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arnold J. N., Wormald M. R., Sim R. B., Rudd P. M., Dwek R. A. (2007) The impact of glycosylation on the biological function and structure of human immunoglobulins. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 25, 21–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kaneko Y., Nimmerjahn F., Ravetch J. V. (2006) Anti-inflammatory activity of immunoglobulin G resulting from Fc sialylation. Science 313, 670–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shields R. L., Lai J., Keck R., O'Connell L. Y., Hong K., Meng Y. G., Weikert S. H., Presta L. G. (2002) Lack of fucose on human IgG1 N-linked oligosaccharide improves binding to human Fcgamma RIII and antibody-dependent cellular toxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 26733–26740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Iida S., Misaka H., Inoue M., Shibata M., Nakano R., Yamane-Ohnuki N., Wakitani M., Yano K., Shitara K., Satoh M. (2006) Nonfucosylated therapeutic IgG1 antibody can evade the inhibitory effect of serum immunoglobulin G on antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity through its high binding to Fc gamma RIIIa. Clin. Cancer Res. 12, 2879–2887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rademacher T. W., Williams P., Dwek R. A. (1994) Agalactosyl glycoforms of IgG autoantibodies are pathogenic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 6123–6127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Huhn C., Selman M. H., Ruhaak L. R., Deelder A. M., Wuhrer M. (2009) IgG glycosylation analysis. Proteomics. 9, 882–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wang J., Balog C. I., Stavenhagen K., Koeleman C. A., Scherer H. U., Selman M. H., Deelder A. M., Huizinga T. W., Toes R. E., Wuhrer M. (2011) Fc-glycosylation of IgG1 is modulated by B-cell stimuli. Mol. Cell Proteomics M110.004655, 1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lastra G. C., Thompson S. J., Lemonidis A. S., Elson C. J. (1998) Changes in the galactose content of IgG during humoral immune responses. Autoimmunity 28, 25–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Guo N., Liu Y., Masuda Y., Kawagoe M., Ueno Y., Kameda T., Sugiyama T. (2005) Repeated immunization induces the increase in fucose content on antigen-specific IgG N-linked oligosaccharides. Clin. Biochem. 38, 149–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gutierrez G., Gentile T., Miranda S., Margni R. A. (2005) Asymmetric antibodies: a protective arm in pregnancy. Chem. Immunol. Allergy 89, 158–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Scherer H. U., Wang J., Toes R. E., van der Woude D., Koeleman C. A., de Boer A. R., Huizinga T. W., Deelder A. M., Wuhrer M. (2009) Immunoglobulin 1 (IgG1) Fc-glycosylation profiling of anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies from human serum. Proteomics. Clin. Appl. 3, 106–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wuhrer M., Porcelijn L., Kapur R., Koeleman C. A., Deelder A., de Haas M., Vidarsson G. (2009) Regulated glycosylation patterns of IgG during alloimmune responses against human platelet antigens. J. Proteome Res. 8, 450–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Scherer H. U., van der Woude D., Ioan-Facsinay A., el Bannoudi H., Trouw L. A., Wang J., Häupl T., Burmester G. R., Deelder A. M., Huizinga T. W., Wuhrer M., Toes R. E. (2010) Glycan profiling of anti-citrullinated protein antibodies isolated from human serum and synovial fluid. Arthritis Rheum. 62, 1620–1629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ercan A., Cui J., Chatterton D. E., Deane K. D., Hazen M. M., Brintnell W., O'Donnell C. I., Derber L. A., Weinblatt M. E., Shadick N. A., Bell D. A., Cairns E., Solomon D. H., Holers V. M., Rudd P. M., Lee D. M. (2010) IgG galactosylation aberrancy precedes disease onset, correlates with disease activity and is prevalent in autoantibodies in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 62, 2239–2248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Umaña P., Jean-Mairet J., Moudry R., Amstutz H., Bailey J. E. (1999) Engineered glycoforms of an antineuroblastoma IgG1 with optimized antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxic activity. Nat. Biotechnol. 17, 176–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Davies J., Jiang L., Pan L. Z., LaBarre M. J., Anderson D., Reff M. (2001) Expression of GnTIII in a recombinant anti-CD20 CHO production cell line: Expression of antibodies with altered glycoforms leads to an increase in ADCC through higher affinity for FC gamma RIII. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 74, 288–294 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Anthony R. M., Nimmerjahn F., Ashline D. J., Reinhold V. N., Paulson J. C., Ravetch J. V. (2008) Recapitulation of IVIG anti-inflammatory activity with a recombinant IgG Fc. Science 320, 373–376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Anthony R. M., Wermeling F., Karlsson M. C., Ravetch J. V. (2008) Identification of a receptor required for the anti-inflammatory activity of IVIG. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 19571–19578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Soonawala D., Rimmelzwaan G. F., Gelinck L. B., Visser L. G., Kroon F. P. (2011) Response to 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) vaccine in HIV-infected patients and the influence of prior seasonal influenza vaccination. PLoS. ONE. 6, e16496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. van Riet E., Retra K., Adegnika A. A., Jol-van der Zijde CM, Uh H. W., Lell B., Issifou S., Kremsner P. G., Yazdanbakhsh M., van Tol M. J., Hartgers F. C. (2008) Cellular and humoral responses to tetanus vaccination in Gabonese children. Vaccine 26, 3690–3695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Selman M. H., McDonnell L. A., Palmblad M., Ruhaak L. R., Deelder A. M., Wuhrer M. (2010) Immunoglobulin G glycopeptide profiling by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 82, 1073–1081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Selman M. H. J., Derks R. J., Bondt A., Palmblad M., Schoenmaker B., Koeleman C. A., van de Geijn F. E., Dolhain R. J., Deelder A. M., Wuhrer M. (2011) Fc specific IgG glycosylation profiling by robust nano-reverse phase HPLC-MS using a sheath-flow ESI sprayer interface. J. Proteomics 75, 1318–1329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nevedomskaya E., Derks R., Deelder A. M., Mayboroda O. A., Palmblad M. (2009) Alignment of capillary electrophoresis-mass spectrometry datasets using accurate mass information. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 395, 2527–2533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Aho Alfred V., K. a. B. W., W. P. J. (1988) The AWK programming Language, Addison-Wesley, Reading, Massachusetts [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wuhrer M., Stam J. C., van de Geijn F. E., Koeleman C. A., Verrips C. T., Dolhain R. J., Hokke C. H., Deelder A. M. (2007) Glycosylation profiling of immunoglobulin G (IgG) subclasses from human serum. Proteomics 7, 4070–4081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stadlmann J., Pabst M., Kolarich D., Kunert R., Altmann F. (2008) Analysis of immunoglobulin glycosylation by LC-ESI-MS of glycopeptides and oligosaccharides. Proteomics 8, 2858–2871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Parekh R. B., Dwek R. A., Sutton B. J., Fernandes D. L., Leung A., Stanworth D., Rademacher T. W., Mizuochi T., Taniguchi T., Matsuta K., Takeuchi F., Nagano Y., Miyamoto T., Kobata A. (1985) Association of rheumatoid arthritis and primary osteoarthritis with changes in the glycosylation pattern of total serum IgG. Nature 316, 452–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shikata K., Yasuda T., Takeuchi F., Konishi T., Nakata M., Mizuochi T. (1998) Structural changes in the oligosaccharide moiety of human IgG with aging. Glycoconj. J. 15, 683–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yamada E., Tsukamoto Y., Sasaki R., Yagyu K., Takahashi N. (1997) Structural changes of immunoglobulin G oligosaccharides with age in healthy human serum. Glycoconj. J. 14, 401–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mizuochi T., Hamako J., Titani K. (1987) Structures of the sugar chains of mouse immunoglobulin G. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 257, 387–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mizuochi T., Hamako J., Nose M., Titani K. (1990) Structural changes in the oligosaccharide chains of IgG in autoimmune MRL/Mp-lpr/lpr mice. J. Immunol. 145, 1794–1798 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Blomme B., Van Steenkiste C., Grassi P., Haslam S. M., Dell A., Callewaert N., Van Vlierberghe H. (2011) Alterations of serum protein N-glycosylation in two mouse models of chronic liver disease are hepatocyte and not B cell driven. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol 300, G833–G842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Parmentier H. K., De Vries, Reilingh G., Lammers A. (2008) Decreased specific antibody responses to alpha-Gal-conjugated antigen in animals with preexisting high levels of natural antibodies binding alpha-Gal residues. Poult. Sci. 87, 918–926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Welsh R. M., O'Donnell C. L., Reed D. J., Rother R. P. (1998) Evaluation of the Galalpha1–3Gal epitope as a host modification factor eliciting natural humoral immunity to enveloped viruses. J. Virol. 72, 4650–4656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Abdel-Motal U. M., Guay H. M., Wigglesworth K., Welsh R. M., Galili U. (2007) Immunogenicity of influenza virus vaccine is increased by anti-gal-mediated targeting to antigen-presenting cells. J. Virol. 81, 9131–9141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Raju T. S. (2008) Terminal sugars of Fc glycans influence antibody effector functions of IgGs. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 20, 471–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hodoniczky J., Zheng Y. Z., James D. C. (2005) Control of recombinant monoclonal antibody effector functions by Fc N-glycan remodeling in vitro. Biotechnol. Prog. 21, 1644–1652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Goulon M., Girard O., Grosbuis S., Desormeau J. P., Capponi M. F. (1972) [Antitetanus antibodies. Assay before anatoxinotherapy in 64 tetanus patients]. Nouv. Presse Med. 1, 3049–3050 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ding H., Tsai C., Zhou F., Buchy P., Deubel V., Zhou P. (2011) Heterosubtypic antibody response elicited with seasonal influenza vaccine correlates partial protection against highly pathogenic H5N1 virus. PLoS. ONE. 6, e17821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Staneková Z., Varečková E. (2010) Conserved epitopes of influenza A virus inducing protective immunity and their prospects for universal vaccine development. Virol. J. 7, 351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wrammert J., Koutsonanos D., Li G. M., Edupuganti S., Sui J., Morrissey M., McCausland M., Skountzou I., Hornig M., Lipkin W. I., Mehta A., Razavi B., Del Rio C., Zheng N. Y., Lee J. H., Huang M., Ali Z., Kaur K., Andrews S., Amara R. R., Wang Y., Das S. R., O'Donnell C. D., Yewdell J. W., Subbarao K., Marasco W. A., Mulligan M. J., Compans R., Ahmed R., Wilson P. C. (2011) Broadly cross-reactive antibodies dominate the human B cell response against 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus infection. J. Exp. Med. 208, 181–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jegerlehner A., Schmitz N., Storni T., Bachmann M. F. (2004) Influenza A vaccine based on the extracellular domain of M2: weak protection mediated via antibody-dependent NK cell activity. J. Immunol. 172, 5598–5605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Huber V. C., McKeon R. M., Brackin M. N., Miller L. A., Keating R., Brown S. A., Makarova N., Perez D. R., Macdonald G. H., McCullers J. A. (2006) Distinct contributions of vaccine-induced immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) and IgG2a antibodies to protective immunity against influenza. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 13, 981–990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Carragher D. M., Kaminski D. A., Moquin A., Hartson L., Randall T. D. (2008) A novel role for non-neutralizing antibodies against nucleoprotein in facilitating resistance to influenza virus. J. Immunol. 181, 4168–4176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Huber V. C., Lynch J. M., Bucher D. J., Le J., Metzger D. W. (2001) Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis makes a significant contribution to clearance of influenza virus infections. J. Immunol. 166, 7381–7388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Vella S., Rocchi G., Resta S., Marcelli M., De Felici A. (1980) Antibody reactive in antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity following influenza virus vaccination. J. Med. Virol. 6, 203–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Burton D. R. (2002) Antibodies, viruses and vaccines. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2, 706–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Buonaguro F. M., Tornesello M. L., Buonaguro L. (2011) New adjuvants in evolving vaccine strategies. Expert. Opin. Biol Ther. 11, 827–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]