Abstract

This qualitative study examined sexual health information networks among urban African American youth living in low-income communities. The authors identified sources, message content, and utility of messages about sex and sexual health in a sample of 15–17-year olds (N = 81). Youth received sexual health information from a variety of sources. Messages from parents and sex education had high utility, whereas messages from the Internet and religion had low utility. Four information network patterns were identified, suggesting considerable variation in how youth are socialized regarding sex. Findings suggest that sexual information networks have the potential to affect sexual health and development.

Adolescence is a period during which young people experience changes in many domains including changes in sexuality (Katchadourian, 1985; Steinberg, 2010). This developmental process is guided by psychological, physical, and social considerations and takes place within the broader context of the community and the culture. The community, through family, peers, schools, and medical professionals, offers a network of information sources that guide this developmental process. Youth may rely on a variety of sources to provide them with information, role modeling, and skill building regarding sexual health. However, there is little consensus concerning how youth should learn about sex (Russell, 2005). Given the central role that sexuality plays throughout the life course, and the importance of sexual developmental during adolescence (Halpern, 2010), it is critical to understand what sources youth rely on for sexual information, and the extent to which those sources provide them with useful information that prepares them for a healthy sexual life.

Conflicting views of adolescent sexuality in the United States may contribute to our general lack of understanding of how youth learn about sex (Abraham, 2011; Savin-Williams & Diamond, 2004). Alongside strong advocates for comprehensive sex education, confidential services, and frank parent-teen communication about sex, there are vocal advocates for abstinence until marriage education, leaving detailed sex “education” until adulthood, and sex-negative perspectives (e.g., sex is bad). Views about sexuality and how to teach young people about sex also vary among U.S. subcultures, within which attitudes and beliefs about sex are shaped by historical forces (e.g., religious, political), and current health issues related to adolescent sex (e.g., teen pregnancy, STIs).

Our work is focused on a specific population, African American youth living in poor urban neighborhoods. Such youth frequently grow up under difficult circumstances that may include poverty, fragmented family situations, resource-poor secondary schools, and limited future opportunities (Anderson, 1999; Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2004). African American youth living in these neighborhoods are more likely to have an early sexual debut and face considerable sexual health challenges, including STIs and pregnancy (Leventhal &Brooks-Gunn, 2004; B. C. Miller, Benson, & Galbraith, 2001). Thus, there is an urgency to understand the network of individuals and institutions that contribute to youth sex education, to understand normative sexual development of these youth, as well as to address their prevention needs.

In considering where and how young people learn about sex, we rely on a bioecological framework that considers the impact of proximal and distal factors on development (Bronfenbrenner & Evans, 2000). This systems approach holds that youth are affected by forces in their immediate environment, by the interaction of the various forces with each other, and by factors in the broader context. The microlevel social systems in the immediate environment (e.g., family, school) have a dynamic relationship at the mesolevel where microsystems interact (Bronfenbrenner & Evans, 2000); these systems may or may not share a common focus. When there is a common focus at the mesolevel, developmental outcomes are more likely to be positive, because the common focus provides reinforcement of values and sustained engagement (Bronfenbrenner & Evans, 2000). This perspective suggests that, in addition to studying the individual sources of information that youth rely on, we should also be considering the dynamic aspect of these sources. This information network approach will allow us to identify patterns that demonstrate how these sources work in concert to provide information and education.

Information Networks: What Do We Know?

There is a significant body of literature that focuses on single sources of information about sex (e.g., mother, peers, medical), or two sources in tandem (e.g., parents and peers; Collins, Elliott, Berry, Kanouse, & Hunter, 2003; Dilorio etal., 2002; M. S. Miller, Kotchick, Dorsey, Forehand, & Ham, 1998), but few studies address the broader scope of sources that may provide important information. Furthermore, studies often focus on the contribution of sources to sexual behavior (e.g., Brown et al., 2006; Chen, Thompson, & Morrison-Beedy, 2010), with less attention to what information is conveyed, or how useful that information is to the adolescent. Several notable exceptions provide insight into the numerous sources that African American youth rely on for sexual information, and to a lesser extent, what youth learn from these sources.

Where do African American youth get information about sex?

In studies focused on ethnically mixed samples or African American samples, youth most frequently get information from family members, peers, teachers, and media (Bleakley, Hennessy, Fishbein, & Jordan, 2009; Kapungu etal., 2010; Teitelman, Bohinski, & Boente, 2009). Among these, friends and family members (usually the mother) are typically the most commonly cited sources for sexual information. For instance, Teitelman and colleagues (2009) found that three fourths of youth in their study mentioned friends as sources for sexual information, with mothers (65%) and teachers (62%) following closely. The ease with which friends communicate about personal issues seems to extend to sexual issues (G. W. Harper, Gannon, Watson, Catania, & Dolcini, 2004; Youniss, 1980). In addition, the large number of youth who report learning about sex from teachers reflects the near universal access to sex education in schools (Robert & Sonenstein, 2010). In the previously noted study, Teitelman et al. (2009) also found that nearly as many youth learned about sex from media sources (57%), whereas medical personnel, family members other than the mother (e.g., siblings, fathers, grandparents), and religious sources are less frequently mentioned as resources for sexual information in a number of studies (Bleakley etal., 2009; Teitelman etal., 2009).

What are the sexual information messages?

In addition to knowing where youth obtain information, it is also important to know what topics and issues are addressed. One recent investigation examined the sexual content covered in discussions with several sources, including parents (mother and fathers) and friends (Kapungu et al., 2010). This study focused on African American adolescents participating in a longitudinal study that was initiated in the Chicago public schools. Data reported here are from the third wave of data collection, at which time youth were nearly age 18 years. Based on a questionnaire that included 17 possible topics covering a wide range of issues (e.g., dating, when to have sex, contraception, spontaneous erections) this investigation found that common messages, whether with family or with friends, included prevention (e.g., condom use), how to prevent pregnancy, STIs, issues related to being a teen parent, benefits of not having sex until older, and the dangers of having a lot of sex partners. Thus, the primary emphasis of communication was on prevention and possible negative outcomes of sex, and less discussion revolved around more neutral topics (e.g., how to act on a date), or on basic sexual development issues (e.g., spontaneous erections). However, the list of topics in this study did not include sex-positive items (e.g., how to enjoy sex).

Two qualitative examinations that included African American samples found that parental communication focused largely on negative consequences (Akers, Schwarz, Borrero, & Corbie-Smith, 2010; Teitelman et al., 2009). Furthermore in the Akers et al. study, which included African American parents and their teens living in a large county on the East Coast, it was noted that there was little provision of information or active support for contraception from parents. In contrast, Teitelman and colleagues (2009) found evidence of active support from parents regarding contraception, but only for their daughters.

In their qualitative investigation of African American and European American female adolescents recruited from a clinic setting, Teitelman and colleagues (2009) examined a range of sexual information sources. In this study, friends were viewed as a source of knowledge about things that adults tended not to discuss (e.g., the meaning of slang terms, nonintercourse sex), and friends shared personal experiences with each other. Boyfriends were not a source of information, but the experience of being in a relationship, or having sex, led girls to new understandings about their own sexuality (e.g., desire). In addition, sex education in schools provided mechanical and technical information that was often not obtained elsewhere, whereas medical providers were seen as a source of information about contraception or other medical issues. Finally, the media was viewed as projecting unrealistic images of relationships, of sex, and of women.

Are there gender differences in sexual information sources and messages?

Given the significant gender differences in sexual socialization (e.g., Pleck, Sonenstein, & Ku, 1993; Tolman, Striepe, & Harmon, 2003), it is, perhaps, not surprising that gender differences have also emerged regarding communication about sex. Overall, females are more likely than males to report communicating with various sources about sexual topics (Kapungu et al., 2010), and studies examining parental communication provide mixed evidence concerning whether the content of a sexually informative communication will differ depending on the gender of the child. For example, one study found that parents focused on contraceptives for females and on condoms for male youth (Akers et al., 2010), whereas another study (Kapungu et al., 2010) found that condom use was one of the most frequently discussed topics with parents for males and females.

Medical care professionals may be an important source of sexual information and opportunities to learn about sexual and reproductive health may arise in standard medical visits, but prior work suggests that females are more likely than males to have this opportunity. Using Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance (YRBS) data, Burstein, Lowry, Klein, and Santelli (2003) found that females who were sexually active were more likely to have had a preventive health visit, whereas this was not true for males; and among the sexually experienced youth in this sample, males were about one half as likely as females to have discussed STIs, HIV, or pregnancy at their health visit (33% vs. 61%).

Information exchange with other sources, such as sexual partners, may also differ for males and females. Based on a review of a large number of qualitative studies, Marston and King (2006) suggested that gender-based social expectations lead to avoidance of open and explicit information exchange for males and females. Furthermore, a qualitative study of primarily ethnic minority males recruited through urban schools found that many of these males were able to communicate and share information with girlfriends/sexual partners, although at the same time they cited challenges in doing so, for example, embarrassment, fear of rejection, and inexperience (Marcell, Raine, & Eyre, 2003). There is reason to believe that adolescents of either gender, who have limited experience with intimacy and with negotiations around sex, would experience some challenges in sharing information on sexual issues. Although these studies provide insight into where, and in some cases, what youth learn about sex and sexual health, the current state of knowledge provides a somewhat fragmented view of this process.

This study aims to fill a gap in the literature by focusing on information networks among urban African American youth. We anticipate finding a broad range of information sources, including sources previously identified in the literature. Our exploratory analyses of networks allows for an examination at the mesosystem level and provides important information about dynamic aspects of information sources, the utility of the information provided by these sources, and the sex and sexual health topics and issues conveyed. Furthermore, by including both genders, and sexually experienced and inexperienced youth, this study provides a more comprehensive view of the information networks of urban African American youth than currently exists.

Method

This study is part of a larger community-based qualitative investigation examining ecological factors that affect social and sexual development among urban African American youth. The study is focused on African American neighborhoods in Chicago, Illinois, and San Francisco, California. The Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) at all sponsoring institutions approved study procedures.

Participants and Procedures

In each city, participants were recruited from several youth-serving, community based agencies in low-income neighborhoods containing significant concentrations of African American youth. Several approaches were used to identify potential participants including nominations by agencies’ staff, approaching youth at the agencies, and snowball sampling.

Eligibility was determined by screening conducted by study staff. Inclusion criteria included: being African American, heterosexually oriented, and between ages 15 and 17. Using purposive sampling, we screened a total of 95 youth; of these, eight youth were deemed ineligible and six youth declined to participate. The final sample consisted of 81 youth (males, n = 41; females, n = 40). One half of the females (n = 20) and three fourths of the males were sexually experienced (n = 31). Sexual experience was defined as having experienced sexual debut. One sexually experienced female completed a partial interview. For this analysis, we used the 19 sexually experienced females with complete data on network related topics.

Semistructured interviews were conducted by highly trained ethnic minority males and females. In the vast majority of cases, youth were interviewed by someone of the same gender. We obtained written informed consent from parent/guardians and assent from youth. Youth received cash remuneration for their participation. Interviews were typically about 2 hours and were digitally recorded, transcribed verbatim, and checked for accuracy by staff.

The Interview Guide

Semistructured interviews were designed to address social ecological factors that may affect social development and sexual health. (The full interview guide is available from the authors.) In this study, we focused on sources of information about sex and sexual health, and the content of sexual health messages.

Data on information network nodes was obtained through querying the participants about sources of sexual information, the messages provided by those sources, and the utility of the messages. We began with open-ended queries about where the respondent had learned about sex and sexual health. This was followed by prompts with respect to the following sources: family (broadly defined), friends, boy/girlfriends, teachers/schools, medical personnel/clinics, religious sources, media, and the Internet. The youth were asked about the information that they had received from each source. First, we provided a general prompt about messages and information received. This was followed by queries about specific content areas of relevance to sexual health including birth control, condoms, STIs, sexual health (e.g., communication about sexual health), abstinence, sexual assertiveness, and number of sex partners. Additionally, we asked youth about their experiences with sex education.

Data Analyses

We employed a case analyses and chart reduction approach in this study. There were several stages to the analyses with reliability checks at each stage. Overall, we used a team approach similar to that described by Stern (1991).

Initially, a subset of transcripts were read and discussed by the analytic team. Then, using a directed content analyses approach (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005), we identified and defined initial codes and developed methods for linking chart material to the transcript and for note taking. Following this, the coder and an investigator completed two rounds of coding and reliability checks on subsets of cases. All remaining cases were coded by the primary coder with periodic checks and revisions in consultation with the investigators. The sources of information and content categories of information (e.g., birth control, STIs, sexual assertiveness) are reflected in Tables 1 through 4. (Complete definitions available from the first author.) We also coded the utility of messages from each source. Utility covered a range of ways that sources could be helpful including provision of information, behavioral help (e.g., taking youth to get birth control), modeling (e.g., how to put on a condom), and support (e.g., being available). Utility was determined through analyses of youths’ discussion of information or messages obtained, as well as through direct questions in the interview about what sources were helpful. All data were entered into charts; the final charts provided data on the number and type of sources, message content, and utility of messages. A similar process was used to develop case summaries, including defining the content and structure of summaries, linking summaries to transcripts, and reliability checks. As case summaries and charts were examined, emergent patterns were identified and verified through discussion; we continued to analyze for patterns until no new patterns emerged (Corbin & Strauss, 2008).

Table 1.

Information Sources and Utility of Sources for Females

| Females

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sexually experienced (n=19) | Sexually inexperienced (n = 20) | |||

| Information source | Used source % (n)a | Source has utility % (n)b | Used source % (n)a | Source has utility % (n)b |

| Friends | 100 (19) | 68 (13) | 100 (20) | 80 (16) |

| Girlfriend or boyfriend | 89 (17) | 65 (11) | 75 (15) | 40 (6) |

| Family | 100 (19) | 100 (19) | 100 (20) | 95 (19) |

| Religion | 16 (3) | 33 (1) | 60 (12) | 17 (2) |

| Medical professional | 95 (18) | 94 (17) | 45 (9) | 67 (6) |

| Media | 89 (17) | 35 (6) | 95 (19) | 63 (12) |

| Internet | 53 (10) | 70 (7) | 45 (9) | 22 (2) |

| Sex education | 89 (17) | 94 (16) | 95 (19) | 100 (19) |

| Other sourcec | 53 (10) | 30 (3) | 45 (9) | 11(1) |

| Other adultd | 63 (12) | 50 (6) | 80 (16) | 44 (7) |

Number that reported source.

Of those who reported source, the number that found it useful.

Other sources included self (common sense, experience), job, outreach materials, condom packaging, community centers.

Other adults included adult staff at community centers, celebrities, teachers, coaches, friends of the family.

Table 4.

Variation in Numbers of Information Topics, Sources and their Utility for Males

| Topic | Sexually experienced (n=31) | Sexually inexperienced (n = 10) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Received information on topic % (n)a | Found topic useful % (n)b | Number of sources for topic M (SD)c,e | Number of useful sources for topic M (SD)d,f | Received information on topic % (n)a | Found topic useful % (n)b | Number of sources for topic M (SD)c,e | Number of useful sources for topic M (SD)d,e | |

| Birth control | 97 (30) | 97 (29) | 4.7 (1.7) | 3.3 (1.9) | 90 (9) | 100 (9) | 4.3 (2.0) | 2.4 (1.5) |

| STI | 100 (31) | 100 (31) | 4.5 (1.7) | 2.9 (1.6) | 100 (10) | 100 (10) | 3.6 (1.3) | 2.7 (1.2) |

| Sexual healthf | 74 (23) | 70 (16) | 2.2 (2.0) | 0.9 (1.4) | 80 (8) | 75 (6) | 1.9 (1.2) | 0.9 (0.9) |

| Abstinence | 61 (19) | 21 (4) | 1.2 (1.3) | 0.1 (0.3) | 80 (8) | 25 (2) | 2.5 (1.7) | 0.2 (0.4) |

| Sexual assertiveness | 94 (29) | 97 (28) | 3.4 (1.9) | 2.4 (1.6) | 100 (10) | 90 (9) | 2.8 (1.3) | 2.2 (1.3) |

| Number of sexual partners | 84 (26) | 42 (11) | 2.8 (2.1) | 0.5 (0.9) | 80 (8) | 50 (4) | 2.8 (2.3) | 0.6 (0.8) |

Number that reported information on topic.

Of those who reported information on topic, the number that found it useful.

Refers to the average number of sources each respondent reported receiving topic information from.

Refers to average number of sources about topic that respondent found useful.

Range of possible sources 0-10.

Sexual health topics included information about learning to communicate about sexual health matters (how or what to communicate, verbal or non-verbal).

Results

Overview

In the sections that follow we present findings on information and utility of sources, and message content. Then, we present the general patterns of information sources found in our sample.

Information sources and utility of sources

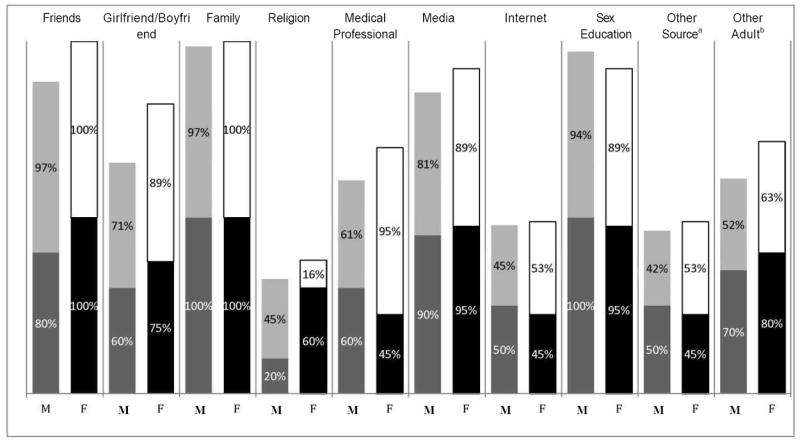

Based on the chart data, we examined the variations in sources of sexual information. Overall, more females than males reported sources of information, and there were some striking differences in sources based on sexual experience (see Figure 1). Among those who reported a source for information, we examined whether the youth found that source to have utility (see Tables 1 & 2). Findings show we found differences in sources and the utility of sources by sexual experience.

Figure 1.

Percent reporting sources by gender and sexual experience. Males = left column: Dark grey (lower) sexually inexperienced; Light grey (upper) sexually experienced. Females = Right column: Black (lower) sexually inexperienced; White (upper) sexually experienced. aOther sources included self (common sense, experience), job, outreach materials, condom packaging, community centers. bOther adults included adult staff at community centers, celebrities, teachers, coaches, friends of the family.

Table 2.

Information Sources and Utility of Sources for Males

| Males

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sexually experienced (n=31) | Sexually inexperienced (n=10) | |||

| Information source | Used source % (n)a | Source has utility % (n)b | Used source % (n)a | Source has utility % (n)b |

| Friends | 97 (30) | 73 (22) | 80 (8) | 25 (2) |

| Girlfriend or boyfriend | 71 (22) | 64 (14) | 60 (6) | 33 (2) |

| Family | 97 (30) | 87 (26) | 100 (10) | 80 (8) |

| Religion | 45 (14) | 21 (3) | 20 (2) | 0 |

| Medical professional | 61 (19) | 89 (17) | 60 (6) | 67 (4) |

| Media | 81 (25) | 56 (14) | 90 (9) | 67 (6) |

| Internet | 45 (14) | 50 (7) | 50 (5) | 40 (2) |

| Sex education | 94 (29) | 83 (24) | 100 (10) | 70 (7) |

| Other sourcec | 42 (13) | 46 (6) | 50 (5) | 40 (2) |

| Other adultd | 52 (16) | 56 (9) | 70 (7) | 71 (5) |

Number that reported source.

Of those who reported source, the number that found it useful.

Other sources included self (common sense, experience), job, outreach materials, condom packaging, community centers.

Other adults included adult staff at community centers, celebrities, teachers, coaches, friends of the family.

The most commonly mentioned sources for sexual information included family and sex education. These two sources were reported as having some utility by nearly all youth (see Tables 1 & 2). Friends were also a highly cited source; all females, and nearly all males, reported getting sexual information from friends. However, the utility of sexual information from friends varied; sexually inexperienced males found friends to be least useful, although sexually experienced females found friends to be most useful. With regard to romantic/sexual partners, we found that sexually experienced males and females were more likely to report boy/girlfriends as a source for useful sexual information than did the sexually inexperienced. A variety of other adults, including coaches, staff at community centers, celebrities, and family friends were also sources of information for youth; sexually inexperienced youth reported these sources to a greater extent than those who had had sex.

Media was cited by the vast majority of youth as a source, but its utility was variable. In general, sexually inexperienced youth viewed media as more useful than those who had had sex. Use of the Internet for sexual information was substantially lower than use of media. In contrast to the findings on media, sexually experienced youth who had used the Internet found it to be more useful than those who had not had sex.

Nearly all sexually experienced females reported having received sexual health information from medical professionals and found that information to have utility. Although fewer sexually experienced males had received information from this source, those who used medical professionals found them to be helpful. Sexually inexperienced males and females less frequently reported talking to medical professionals around issues of sex, and they less often found it to have utility.

Other sources of sexual information covered a mix of situations including learning about sex at a job, through outreach materials, information provided on condom packages, and through community centers. Such sources were less often mentioned, and they were not as useful as many of the other sources mentioned. Finally, religious sources were infrequently mentioned and were seldom viewed as useful.

Message content

Information on sex covered a range of topics including pregnancy prevention and STIs, sexual health (e.g., communication about sex), abstinence, sexual assertiveness, and numbers of partners. Among females, nearly all respondents had received messages about most of these topics and perceived the information to have utility (see Table 3). Among males, all respondents had received STI information, and most had also received messages about birth control (see Table 4); the information was generally found to have utility. Although many males received information about numbers of sexual partners, this information was deemed to have low utility. Finally, males and females received messages from more sources about STIs and birth control than about any other topics.

Table 3.

Variation in Numbers of Information Topics, Sources and their Utility for Females

| Topic | Sexually experienced (n=19) | Sexually inexperienced (n = 20) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Received information on topic % (n)a | Found topic useful % (n)b | Number of sources for topic M (SD)c,e | Number of useful sources for topic M (SD)d,e | Received information on topic % (n)a | Found topic useful % (n)b | Number of sources for topic M (SD)ce | Number of useful sources for topic M (SD)de | |

| Birth control | 100 (19) | 100 (19) | 5.6 (0.8) | 3.9 (1.5) | 100 (20) | 100 (20) | 4.7 (2.0) | 3.1 (1.4) |

| STI | 100 (19) | 100 (19) | 5.3 (1.7) | 3.9 (1.6) | 100 (20) | 100 (20) | 4.2 (2.0) | 2.8 (2.0) |

| Sexual healthf | 95 (18) | 83 (15) | 3.3 (2.0) | 1.5 (1.2) | 100 (20) | 85 (17) | 2.6 (1.5) | 1.1 (0.8) |

| Abstinence | 63 (12) | 17 (2) | 1.2 (1.6) | 0.1 (0.3) | 90 (18) | 22 (4) | 2.0 (1.7) | 0.3 (0.7) |

| Sexual assertiveness | 100 (19) | 100 (19) | 4.1 (2.0) | 3.1 (1.6) | 100 (20) | 95 (19) | 3.4 (1.8) | 2.2 (1.5) |

| Number of sexual partners | 95 (18) | 50 (9) | 3.1 (1.9) | 0.7 (0.9) | 100 (20) | 50 (10) | 4.0 (1.9) | 0.7 (0.9) |

Number that reported information on topic.

Of those who reported information on topic, the number that found it useful.

Refers to the average number of sources each respondent reported receiving topic information from.

Refers to average number of sources about topic that respondent found useful.

Range of possible sources 0-10.

Sexual health topics included information about learning to communicate about sexual health matters (how or what to communicate, verbal or non-verbal).

Abstinence messages stood out in contrast to other topics; fewer respondents received abstinence messages from fewer sources, and abstinence messages were generally perceived as having low utility. Sexually inexperienced youth were more likely to report receiving abstinence messages, and they received messages from more sources on this topic (see Tables 3 & 4). Even so, only 20% to 25% of sexually inexperienced youth who received abstinence messages found them to have utility.

In summary, youth received sexual information from a variety of sources in their networks on topics important to sexual health, and which the youth found to be helpful. The data also indicate that there is variability in these messages and in the utility of the messages. Thus, the data suggest that there may be network patterns that differ within the sample.

Network Patterns: Case Studies

Case analyses provide a means of illustrating network patterns that emerged in this study, providing insight into how individual sources of information are dynamically related at the mesosystem level. Through this approach, we describe the variation in sexual information networks, and how these variations may contribute differently to youths’ sexual health development. Three general information network patterns emerged, which are defined below, and are presented using an exemplar of each pattern. The first pattern reflected networks that were rich, consistent, and provided prevention messages. The second pattern reflected sparse networks, and the third pattern revealed inconsistent networks. A fourth pattern was observed only among sexually inexperienced youth; this pattern was highly sex negative and observed in a small minority of youth.

Rich and consistent networks

The first information network pattern revealed rich and consistent networks, which were found among sexually experienced and inexperienced respondents. These youth reported many sources of information about sex, which often contributed to skill building and opportunities for modeling. Another feature of these networks was the consistency of information across the network: youth heard the same messages repeatedly from a variety of sources. Messages were primarily focused on prevention.

Latisha, a 15-year-old sexually experienced female, exemplifies this pattern. This respondent received sex education at school and through an after school program. Her school-based sex education covered all major sexual health topics, used a variety of approaches to convey information (e.g., instruction, guest speakers, group discussion), and included information on the importance of getting to know, and be able to communicate with, a partner prior to having sex. In addition, Latisha had a science teacher who addressed sexual and reproductive issues in class, and her after-school program provided a safe and supportive location for teens during the hours after school, offering workshops on a variety of issues, including sex and discussions of the future.

The messages obtained at school were reinforced through Latisha’s contact with medical professionals. During clinic visits, she received information about birth control and STIs, and she also received prevention messages. Latisha is currently using hormonal birth control and condoms, and she finds that condoms are available in the community.

Latisha’s female family members (i.e., mother, sister, and grandmother), friends, and her boyfriend all provided encouragement and support for STI prevention and birth control. For example, she learned from her boyfriend to check the condom during sex to make sure it was still in place. Latisha also noted that her best friend thinks everyone should use condoms, or at a minimum use birth control.

In addition to learning about STI testing from friends, Latisha also got tested for STIs with friends. She and several friends got tested together, after one of them had her sexual debut without using a condom. “We’ll all just make an appointment. We’ll all get tested together. But that’s just my close friends, I don’t do that with many people.”

The consistency in the messages Latisha received from numerous sources is also striking. In the section below, we see how messages from sex education, medical environments, and family come together to provide information about condoms, supplementing the social support from her boyfriend and best friend.

R: I learned about condoms all in school and at the clinics.

I: Ok, what did you hear about condoms from the teachers?

R: It’s safe. It prevents pregnancy. And, it lowers your chances of having a disease unless you already had unprotected sex before using the condoms.

I: And, clinics, what did you learn about condoms from clinics?

R: How you use them, what they help you prevent, and where you can get them.

I: Did you learn anything about condoms from family?

R: My mom, my sister.

I: Ok, what did they share?

R: They just told me if I ever decide to have sex to come to them first and if I do have sex and don’t come to them to be sure to protect myself.

Furthermore, Latisha has seen a number of important sexual health practices modeled or normalized through the media. She recalled movies or TV shows that included scenes where the actors used condoms; she also recalled shows that depicted teen pregnancy and its consequences, and teens seeking sexuality advice from others. The missing nodes for Latisha included the Internet and religious sources. Although she attends church, she did not receive any sexual information from this source.

Among youth with rich and consistent networks a variety of learning experiences were found. Of particular importance were opportunities for modeling and reinforcement of positive sexual health practices. For example, several out-of school programs provided contact with adults and other youth who placed high value on positive and safe sexual relationships. For instance, a sexually experienced 17-year-old male described his experience in an advocacy program “… We learned about … diseases, … abstinence, … how to conduct ourselves in a relationship…. We have to understand what type of people we are and what we want out of the relationship, our perspective on love.”

Another male recounted the importance of his job with a sexual health program:

…the lady I used to work with … taught me the majority of the stuff I know about HIV-AIDS [and] still carry on to this day … Basically everything I know today: about using condoms and protecting myself the right way.

Other youth had families or other adults who modeled important behaviors for them. In one case, a mother provided specific modeling for her daughter on how to communicate with partners. “I learned to talk to him from my mom like how to start it, like ‘Oh, so babe, I was thinking about using birth control. What do you think about that?”

In another case, a best friend’s aunt provided an opportunity to consider multiple points of view, a skill that many teens may not have developed, and which can be critical in developing strong relationships. A sexually inexperienced female described what she learned:

She also taught us … condoms are good but at another point … she was trying to let us see two points of view … like her point of view and the guy point of view…. So that’s just … little things that she was throwing in there when we had a talk about getting sexual active.

Sparse networks

The second pattern identified were networks that tended to be sparse with few sources that only provided perfunctory information. In these networks, critical sources were missing; some youth had only three or four sources for information. Additionally, messages in these networks tended to be admonishments (e.g., use condoms, don’t have sex), with little in the way of constructive messages or opportunities to build skills for healthy sexual activity. For example, Richard, a sexually experienced 16-year-old reported only three sources for sexual information: friends, family, and the media. The only information Richard received from family came from his grandmother and was essentially a wives-tale about how to tell if a girl has an STI. He is one of a minority of youth who have not had any sex education.

Friends and the media provided information about two or three content areas, some of which was useful. Richard’s exposure to sex information on TV is from a commercial about HIV that explains where to get tested. The excerpts below provide some insight into how little sexual health information this adolescent male has.

I: I’m wondering how much you know about birth control.

R: I’m clueless about birth control.

I: Ok, so has anybody ever talked to you about birth control? Be it friends, family members.

R: Nope.

And at another point in the interview:

I: Ok. So, where did you learn about where to go if you thought you had an STD?

R: My friend. He said one time he went to go get checked up.

I: Ok. He told you where he went?

R: Nope.

Other youth with this type of network have limited information on important topics such as STI testing or assertiveness. For example, Elijah, a 15-year-old sexually inexperienced male with only four sources of sexual information, knew that he should go to a clinic if he thought he had an STI, but he had no information beyond that. “Well, all they [sex education teachers] told me is go to the clinic. That’s what they told me. She told us that—let’s see, she just told us to go a health clinic as soon as possible.” Likewise, a sexually inexperienced female whose only sources for sexual information come from sex education and the media has a very limited idea of how to avoid unwanted sex. She described what she has seen in movies: “Some movies, they just run or something, or they just slap them or something.”

Inconsistent networks

The third pattern we identified reflected inconsistent sexual information networks. These networks provided confusing or contradictory messages to youth. In these networks, one or two sources promoted abstinence, whereas other sources promoted safer sex. The youth appeared to struggle to try to bring these contradictory messages into focus.

A 16-year-old sexually experienced male Darrell represents this pattern. Although Darrell has had sex in the past, he is currently abstinent. He has received prevention messages from a medical practitioner from whom he got advice regarding STIs, his friends, and the Internet, where he also learned about treating STIs. In contrast, Darrell, who is deeply religious and attends weekly Bible study classes and church services, has received strong proabstinence until marriage messages from religious sources. Regarding teens and sex he says:

… that a person shouldn’t have sex until they are married…. That’s what it says in the Bible. People don’t go by the Bible, they just go by their first instinct are and like try to make it easy for them to have sex…

He seems conflicted about sex, stating that sex outside of marriage is a sin while also stating that a person needs to decide when they are “ready” to have sex. Darrell’s sex education has also been mixed. He has received abstinence messages in an after-school program, and at the same time he received information about how to use condoms in his school-based sex education program. “I learned how to put on a male condom [and] … how to put on female condoms.” (Interestingly, he did not attend the full sex education course at school.) In a science course, also at school, he was introduced to some websites where health information could be obtained. Darrell then used the Internet to find information on STIs. “On the Internet … I looked for the different type of diseases like what can that lead to or what type of medicine should you take to prevent that.”

In addition to providing conflicting messages, his network is not as rich as some youth. Darrell has received no messages from the media or family regarding sex, and friends and girlfriends have only given information about birth control. The most useful sources have been the school-based sex education program and his doctor. Importantly, his doctor is his longtime medical practitioner, and Darrell received sexual health messages through his regular medical visits. One topic he has gotten information on is condom use: “He [doctor] said that use a condom and strap up—if you use a condom it’ll prevent you from making a baby.”

Inconsistent network patterns were evident for sexually inexperienced youth. One sexually inexperienced female with a fairly broad network got abstinence messages and prevention messages from family, sex education programs, and religious sources.

I’ve heard like pastors and stuff say that you should take it [birth control], but I’ve heard some say … just like with the abstinence thing, you say you should but they try to stress like, “But you really shouldn’t have to, because you should be married when you’re having sex,” and stuff like that.

… at my school they so on us about abstinence, but one of my gym teachers, she—she talks about it. She just says if you gonna have sex; try to get on some type of birth control.

In these cases, there appear to be few opportunities for resolving these conflicting messages, for gaining skills to avoid unwanted sex, or to engage in negotiation of safer sex.

Sex-negative networks

Among the sexually inexperienced respondents we noted an additional pattern, one that was sex negative. Although this pattern was observed in a small subset of the sample, it suggests a concerning set of circumstances that will likely have long-term consequences for youth. Virtually all of the messages these youth received were sex negative or perceived as sex negative.

Lisa, a 15-year-old sexually inexperienced female, is an exemplar of this pattern. This youth attends a Christian high school and does not expect to have sex until she is married. Her sexual health network is limited and presents a consistent message that sex is negative and associated with negative outcomes. She views sex, and sex-related bodily functions, in negative terms. She does not anticipate that sex can be pleasurable and described discussions with friends or boyfriend about birth control or condoms as weird or troublesome.

I: What did you learn from [friends]?

R: Well, my friends, I have two of them who are on birth control. And one of them, she was like, I was like, so what do you take pills? And she was like, no, I got a shot. And I’m like, what? So I just was like, I didn’t go into the private details. And then my friend was all like, the other one, she was like, I can’t believe this birth control. I haven’t had a period. And I’m like, what? Like, why would you say this to me at lunch? Like, it was so weird, I’m like please don’t talk about this, like, ever.

I: Have you learned about condoms from boyfriends?

R: He told me like, … yeah, my dad just bought me some condoms. He just said it like it was cool, and I’m like, okay. And he was like, yeah, they’re large, or something. And I was just like, why are you telling me this? Like, I really don’t care. Oh God, I have to deal with you.

Furthermore, Lisa had comprehensive sex education in eighth grade, but what she remembers is only related to information about condom failures, whereas her high school sex education program promotes abstinence only.

At my school now, they teach us, … about making decisions and we get this packet … tells me about the things that you value the most. It kinds of tricks you but it’s kinda things you value the most and on a scale, 1 through 10 … and it was like would you give up all that for a boy and sex? And it’s like, no, like who would? So it’s like why risk that? And then it gets you into all of the different things about pregnancy and all that stuff so that’s the only thing I’ve been taught.

In addition, Lisa received almost no information from her family about sexual health. Her mother won’t talk about sex but tells her not to have it, and she has received no information about sex from medical professionals.

Discussion

Learning about sex is an important part of adolescent development, and teens rely on a variety of sources to educate them in this regard. This study contributes to a scant literature that examines a broad range of information sources, topics, and utility of sexual information among urban African American youth. Furthermore, our analyses of the patterns of sexual information networks are a cause for optimism, but also suggest that there is work to be done to facilitate sexual health development in this population.

Our findings contribute to an understanding of the sources that urban African American youth rely on for information about sex. Similar to other studies, family and friends stood out as frequent sources of information. Sex education was nearly universal and had high utility. Few youth had sex education experiences that were focused only on abstinence, perhaps reflecting convincing evidence of the relative value of comprehensive sex education, over abstinence only education, and the shift away from federal funding for abstinence-only programs (Kirby, Laris, & Rolleri, 2007; Kohler, Manhart, & Lafferty, 2008). It is important to note that comprehensive sex education is more likely than abstinence only education to prepare youth for their future, as sex is a normative adult activity.

Although prior work has shown that the media is a source of information for youth, our findings suggest that the media has less credibility than other sources. The messages portrayed through the media are often not prevention focused nor sex positive (Farrar et al., 2003), and this may be the reason that youth find this source less useful. Another source commonly cited as potentially important for sexual information is the Internet. However, Internet use among the youth was lower than the media, and it did not have high utility. There are numerous credible sexual health Internet sites (e.g., iwannaknow.org, plannedparenthood.org) that youth may be unaware of or unable to access. The Internet and the media could be strengthened to serve a more active role in sexual health education.

The importance of the medical profession as a source of information was striking, especially for sexually experienced females. Many adolescent females are obtaining birth control and receiving general prevention messages from medical professionals. Adolescent males also receive access to condoms and prevention messages at medical visits. Our findings that sexually inexperienced youth received little information from medical sources reinforce other calls for greater attention to sexual health during pediatric preventive visits (C. C. Harper et al., 2010; Ott, 2010).

Our findings support prior work demonstrating some gender differences in communication about sexual health. Females were more likely to have received information about sex from many of the sources examined, including friends, boyfriends/girlfriends, and religious sources. As noted above, some of these differences were most striking among the sexually inexperienced. Further work that examines gender differences in sources of sexual information, and differences in messages for those who have not yet had sex, will contribute to our understanding of how to prepare youth for their sexual debut.

As noted elsewhere, within disadvantaged neighborhoods there are strengths as well as challenges (Brooks-Gunn, Duncan, & Aber, 1997; Stoddard, Henly, Sieving, & Bolland, 2010), and we found this to be true with regard to information networks. From the vantage point of sexual health information networks, our findings provide insight into how sources of importance starting in early childhood (e.g., family), as well as sources that contribute at later points (e.g., school, medical professionals), shape a youth’s views of sex, level of information, and skills. This dynamic fits with theoretical perspectives that suggest that a mesosystem level of analyses provides critical information that is important to development.

In relation to the four patterns identified in this study, youth who had rich and consistent networks are getting positive and varied messages about important sexual health topics and often also receive modeling that reinforces positive messages. These youth are likely to be well prepared to have sex, and in a better position to make informed decisions. In contrast, youth with sparse networks may not be getting the breadth of information they need to make informed decisions about sex. Although having a sparse network has limitations, those with inconsistent networks or sex negative networks may experience the most difficulties. When youth receive contradictory messages from respected sources, they may feel conflicted. These young people may need additional support to sort out their values about sex, and to be prepared if they choose to have sex. Furthermore, youth who receive sex-negative messages may have considerable difficulty achieving a satisfactory sexual life as they develop into adults unless they are able to overcome their perceptions of sex as unwholesome.

Building on ecological models (Altman & Goodman, 2001; Bronfenbrenner & Evans, 2000), and on the information network patterns observed in this study, we believe that community-based intervention approaches to strengthen networks and to broaden messages hold considerable promise. Currently, the various sexual information sources tend to function independently and sometimes ineffectively; whereas approaches that connect sources and encourage families, medical professionals, schools, and other youth-focused organizations to work collaboratively would go far in reinforcing messages and ensuring that content areas are covered. Additionally, approaches that focus on the development of a mature and positive sexual life would supplement the current trend, which is focused primarily on prevention (also see Abraham, 2011; Halpern, 2010).

Limitations

This investigation focused on urban African American youth between ages 15 and 17 living in two U.S. cities, and findings may not generalize to other populations or age groups. Because qualitative studies require smaller samples, this study is based on 81 youth. Our sampling methods do not provide a basis for making generalizations about the prevalence of patterns observed. However, this study provides rich data that can be used to design larger quantitative investigations that pursue issues of importance related to information networks that have emerged.

Future Directions and Conclusions

Sexual information networks may serve a critical role in sexual development. The breadth, depth, and content of messages about sex may shape youths’ general orientation toward, and perceptions of sex, contributing to sex-positive or sex-negative orientations. Thus, future studies addressing the impact of information networks on sexual development are warranted. Furthermore, investigations that examine the association between network patterns, and whether youth are prepared for sex, have the potential to provide additional insight into the role of networks on adolescent sexual behavior.

Our findings suggest wide variation in the sources and messages that urban African American youth receive regarding sexual health. That many youth are getting information on a variety of sexual health issues from multiple sources suggests that there is a foundation on which to build community-based network focused interventions. Thus, interventions that draw on the strengths of the community, and connect the various sources that affect youth, have the potential to positively affect sexual health among these youth.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Grant Number R01 HD061027-01, awarded to M. Margaret Dolcini. The authors thank Lauren Fontanarosa, Senna Towner, and Marcia Macomber for their contributions to the work on this manuscript, and Eli Anderson for his consultation on the project. The authors also thank the community-based organizations and youth participants who shared their time and perspectives to this research.

References

- Abraham L. Teaching good sex. A frank, fearless approach to the birds and the bees. Introducing pleasure to the peril of sex education. New York Times Magazine. 2011 November 20;:36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Akers AY, Schwarz EB, Borrero S, Corbie-Smith G. Family discussions about Contraception and family planning: A qualitative exploration of black parent and adolescent perspectives. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2010;42(3):160–167. doi: 10.1363/4216010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman DG, Goodman RM. Community interventions. In: Baum A, Revenson TA, Singer JE, editors. Handbook of health psychology. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2001. pp. 591–612. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E. Code of the street: Decency, violence, and the moral life of the inner city. New York, NY: W.W Norton; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bleakley A, Hennessy M, Fishbein M, Jordan A. How sources of sexual Information relate to adolescents’ beliefs about sex. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2009;33(1):37–48. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2009.33.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, Evans GW. Developmental science in the 21st century: Emerging questions, theoretical models, research designs and empirical findings. Social Development. 2000;9(1):115–125. doi: 10.1111/1467-9507.00114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan GJ, Aber JL, editors. Neighborhood poverty Policy implications in studying neighborhoods. II. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Brown JD, L’Engle KL, Pardun CJ, Guo G, Kenneavy K, Jackson C. Sexy media matter: Exposure to sexual content in music, movies, television, and magazines predicts black and white adolescents’ sexual behavior. Pediatrics. 2006;117(4):1018–1027. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burstein GR, Lowry R, Klein JD, Santelli JS. Missed opportunities for sexually transmitted diseases, human immunodeficiency virus, and pregnancy prevention services during adolescent health supervision visits. Pediatrics. 2003;111(5 Pt 1):996–1001. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.5.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen AC, Thompson EA, Morrison-Beedy D. Multi-system influences on adolescent risky sexual behavior. Research in Nursing and Health. 2010;33:512–527. doi: 10.1002/nur.20409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Elliott MN, Berry SH, Kanouse DE, Hunter SB. Entertainment television as a healthy sex educator: The impact of condom-efficacy information in an episode of Friends. Pediatrics. 2003;112(5):1115–1121. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.5.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dilorio C, Resnicow K, Thomas S, Dongqing TW, Dudley WN, Van Marter DF, Lipana J. Keepin’ it r.E.A.L.!: Program description and results of baseline assessment. Health Education and Behavior. 2002;29(1):104–123. doi: 10.1177/109019810202900110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrar K, Kunkel D, Biely E, Eyal K, Fandrich R, Donnerstein E. Sexual Messages during prime-time programming. Sexuality & Culture: An Interdisciplinary Quarterly. 2003;7(3):7–37. doi: 10.1007/s12119-003-1001-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern CT. Reframing research on adolescent sexuality: Healthy sexual Development as part of the life course. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2010;42(1):6–7. doi: 10.1363/4200610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper CC, Henderson JT, Schalet A, Becker D, Stratton L, Raine TR. Abstinence and teenagers: Prevention counseling practices of health care providers serving highrisk patients in the United States. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2010;42(2):125–132. doi: 10.1363/4212510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper GW, Gannon C, Watson SE, Catania JA, Dolcini MM. The role of close friends in African American adolescents’ dating and sexual behavior. Journal of Sex Research. 2004;41(4):351–362. doi: 10.1080/00224490409552242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapungu CT, Baptiste D, Holmbeck G, McBride C, Robinson-Brown M, Sturdivant A, Paikoff R, et al. Beyond the “birds and the bees”: Gender differences in sex-related communication among urban African-American adolescents. Family Process. 2010;49(2):251–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2010.01321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katchadourian HA. Fundamentals of human sexuality. 2. New York, NY: Holt, Reinhart and Winston; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby DB, Laris BA, Rolleri LA. Sex and HIV education programs: Their impact on sexual behaviors of young people throughout the world. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;40(3):206–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.11.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler PK, Manhart LE, Lafferty WE. Abstinence-only and comprehensive sex education and the initiation of sexual activity and teen pregnancy. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;42(4):344–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. Diversity in developmental trajectories across adolescence: Neighborhood influences. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology. 2. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2004. pp. 451–486. [Google Scholar]

- Marcell AV, Raine T, Eyre SL. Where does reproductive health fit into the lives of adolescent males? Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2003;35(4):180–186. doi: 10.1363/psrh.35.180.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marston C, King E. Factors that shape young people’s sexual behaviour: A systematic review. The Lancet. 2006;368(9547):1581–1586. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(06)69662-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BC, Benson B, Galbraith KA. Family relationships and adolescent pregnancy risk: A research synthesis. Developmental Review. 2001;21(1):1–38. doi: 10.1006/drev.2000.0513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KS, Kotchick BA, Dorsey S, Forehand R, Ham AY. Family Communication about sex: What are parents saying and are their adolescents listening? Family Planning Perspectives. 1998;30(5):218–222. 235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott MA. Examining the development and sexual behavior of adolescent males. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46(4):S3–S11. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL, Ku LC. Masculinity ideology: Its impact on Adolescent males’ heterosexual relationships. Journal of Social Issues. 1993;49(3):11–29. [Google Scholar]

- Robert AC, Sonenstein FL. Adolescents’ reports of communication with their parents about sexually transmitted diseases and birth control: 1988, 1995, and 2002. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46(6):532–537. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell S. Conceptualizing positive adolescent sexuality development. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 2005;2(3):4–12. doi: 10.1525/srsp.2005.2.3.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC, Diamond LM. Sex. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology. 2. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2004. pp. 189–231. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. Adolescence. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Stern PN. Are counting and coding a cappella appropriate in qualitative research? In: Morse JM, editor. Qualitative nursing research: A contemporary dialogue. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1991. pp. 147–162. [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard SA, Henly SJ, Sieving RE, Bolland J. Social connections, trajectories of hopelessness, and serious violence in impoverished urban youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;40(3):278–295. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9580-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teitelman AM, Bohinski JM, Boente A. The social context of sexual health and sexual risk for urban adolescent girls in the United States. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2009;30(7):460–469. doi: 10.1080/01612840802641735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolman D, Striepe MI, Harmon T. Gender matters: Constructing a model(s) of adolescent sexual health. Journal of Sex Research. 2003;40(1):4–12. doi: 10.1080/00224490309552162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youniss J. Parents and peers in social development: A Sullivan-Piaget perspective. Chicago, IL; University of Chicago Press: 1980. [Google Scholar]