Background: Up-regulated in various cancers, API5 prevents apoptosis under growth factor deprivation.

Results: We have determined the crystal structure of API5 with the HEAT and ARM repeat and show that Lys-251 acetylation is important for its function.

Conclusion: API5 likely serves as a scaffold for multiprotein complex with its cellular function regulated by lysine acetylation.

Significance: Structural basis of API5 function is important in targeting anti-apoptosis.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Cancer, Drug Resistance, Protein Assembly, Protein Structure, AAC-11, API5, Armadillo Repeat, HEAT Repeat, Lysine Acetylation

Abstract

Apoptosis inhibitor 5 (API5) is an anti-apoptotic protein that is up-regulated in various cancer cells. Here, we present the crystal structure of human API5. API5 exhibits an elongated all α-helical structure. The N-terminal half of API5 is similar to the HEAT repeat and the C-terminal half is similar to the ARM (Armadillo-like) repeat. HEAT and ARM repeats have been implicated in protein-protein interactions, suggesting that the cellular roles of API5 may be to mediate protein-protein interactions. Various components of multiprotein complexes have been identified as API5-interacting protein partners, suggesting that API5 may act as a scaffold for multiprotein complexes. API5 exists as a monomer, and the functionally important heptad leucine repeat does not exhibit the predicted a dimeric leucine zipper. Additionally, Lys-251, which can be acetylated in cells, plays important roles in the inhibition of apoptosis under serum deprivation conditions. The acetylation of this lysine also affects the stability of API5 in cells.

Introduction

Apoptosis, a programmed cell death process, plays important roles in sculpting the developing organism and in maintaining cell number homeostasis (1, 2). It is also critical for effective cancer chemotherapy (3). Two main pathways of apoptosis have been studied extensively. The extrinsic pathway is mediated by interactions between the death receptors and death ligands. This induces the formation of the death-inducing signaling complex and caspase-8 (4). The intrinsic pathway, which is triggered by radiation, drugs, reactive oxygen species, and radicals, begins with the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria, which ultimately activates caspase-9 (4, 5). These pathways converge downstream, as both caspase-8 and caspase-9 activate caspase-3 (4, 6). Activated caspases cleave specific target proteins, such as protein kinases, cytoskeletal proteins, and DNA repair proteins, initiating apoptosis (6, 7). The characteristic markers of apoptosis include cell and nuclear shrinkage, DNA cleavage into nucleosomal fragments, chromatin aggregation, and apoptotic body formation (8). Because the precisely regulated events of apoptotic cell death are frequently altered in cancers, proteins in the apoptotic pathway can represent good targets for anti-cancer drugs (9).

Inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP)3 family proteins are negative regulators of apoptosis and were characterized originally as physical inhibitors of caspases (10). Eight IAP proteins have been identified, and each of these proteins contains an ∼70-amino acid BIR (baculovirus IAP repeat) domain that mediates protein recognition and interactions (11). Some IAPs include additional domains, such as a RING (really interesting new gene) domain, UBA (ubiquitin-associated domain), or CARD (caspase recruitment domain). Anti-cancer drugs that target IAPs by mimicking the N-terminal IAP binding motif (Ala-Val-Pro-Ile) of Smac are currently in clinical trials for some solid tumors and lymphomas (12).

API5 (apoptosis inhibitor 5), also known as AAC-11 protein (anti-apoptosis clone 11), FIF (fibroblast growth factor 2-interacting factor), and MIG8 (cell migration-inducing gene 8), is a relatively poorly studied apoptosis-inhibiting nuclear protein that does not contain a baculovirus IAP repeat domain. The API5 gene has been found in animals, protists, and plants (13). The expression of API5 prevents apoptosis following growth factor deprivation, and this protein is up-regulated in various cancer cells (14–19). Non-small cell lung cancer patients whose cancers express API5 have a poorer prognosis than patients with non-API5-expressing cancers, and overexpression of API5 promotes the invasion and inhibits apoptosis in cervical cancer cells (15, 17, 20). It has been suggested that API5 suppresses E2F1 transcription factor-induced apoptosis (21). A recent study also suggested that API5 is phosphorylated by PIM2 kinase and inhibits apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells through NF-κB (nuclear factor-κB) (22). Various API5 interaction partners have been identified. API5 interacts with high molecular mass forms of fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2), which are involved in cell proliferation and tumorigenesis (16). API5 also binds to and regulates Acinus, a protein involved in chromatin condensation and DNA fragmentation during apoptosis (23). Moreover, the inhibition of API5 increases anti-cancer drug sensitivity in various cancer cells (23). Recently, the chromatin remodeling enzyme ALC1 (amplified in liver cancer 1) and two DEAD box RNA helicases were identified as binding partners of API5 (13, 24). From these data, API5 has been regarded as a putative metastatic oncogene and therefore represents a therapeutic target for cancer treatment (23). The rational design of inhibitors of API5 will be aided by determination of its three-dimensional structure. Additionally, the lack of sequence similarity between API5 and other known proteins has made it difficult to predict its molecular function. Therefore, structural information about API5 will be helpful in elucidating its molecular function.

We determined the crystal structure of human API5 to elucidate the molecular basis of its anti-apoptotic function. API5 contains a multiple helices, forming HEAT and ARM (Armadillo)-like repeats, which are known to function in protein-protein interactions. This study thus reveals that API5 acts as a mediator of protein interactions.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Protein Expression and Purification

The human API5 gene (full-length (1–504), API5ΔC (1–454)) was amplified by PCR and cloned into pET28b(+) (Novagen) using NdeI and NotI restriction sites. This construction adds a 21-residue tag including His6 to the N-terminal of the recombinant protein, facilitating protein purification. The mutants (K251Q, K251R, and K251A) of the API5 gene were prepared by QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis method using the wild type plasmid as the PCR template. The wild type and mutant proteins were overexpressed in Escherichia coli Rosetta2(DE3) cells (Novagen). The cells were grown at 37 °C in 4 liters of Terrific Broth medium to an A600 of 0.7, and expression of the recombinant protein was induced with 0.5 mm isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside at 37 °C. The cells were grown at 37 °C for 16 h after isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside induction and were harvested by centrifugation at 3000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The cell pellet was suspended in ice-cold lysis buffer (25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 138 mm NaCl, 2 mm KCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 0.8 μm lysozyme) and homogenized by sonication. The first purification step utilized a Ni2+ nitrilotriacetic acid column (Qiagen) for affinity purification via the N-terminal His6 tag. The eluent was pooled and concentrated. The protein sample was diluted 10-fold with buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 80 mm NaCl, and 1 mm DTT). Further purification was conducted using a HiTrap Q ion exchange chromatography column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 80 mm NaCl, and 1 mm DTT). The protein was eluted using a linear gradient of 0–1.0 m sodium chloride in the same buffer. The final purification step was gel filtration on a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 prep-grade column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with buffer containing 20 mm sodium citrate, pH 5.5, 200 mm NaCl, and 1 mm DTT. The purified API5 protein was concentrated to ∼20 mg/ml using an YM10 membrane (Millipore). Human α-thrombin (Enzyme Research Laboratories) or porcine trypsin (Promega) was used to remove the fusion tag or to achieve limited proteolysis, respectively.

Crystallization, X-ray Data Collection, and Structure Determination

The best crystals were obtained with a reservoir solution of 10% PEG 6000 and 100 mm bicine, pH 9.0, using the API5ΔC protein. For x-ray diffraction data collection, crystals were transferred to a cryoprotectant solution (10% PEG 6000, 100 mm Bis-Tris, pH 6.0, and 30% ethylene glycol) and mounted on nylon loops. Data of API5ΔCs (wild type and K251Q mutant) were collected using an ADSC Quantum CCD detector at the 4A and 6C experimental stations, Pohang Light Source, Korea and an ADSC Quantum 4 CCD detector at the BL-1A experimental station, Photon Factory, Japan, respectively. Intensity data were processed and scaled using the program HKL2000 (25). Selenium sites were located with SOLVE (26) using two MAD data sets. Initial phases were improved using the program RESOLVE (26). Manual model building was performed using the program COOT (27), and the model was refined with the program PHENIX (28) and Refmac (29), including bulk solvent correction. As the test data for the calculation of Rfree, 5% of the data were randomly set aside (30). The refined models were evaluated using MolProbity (31).

Analytical Ultracentrifugation

Equilibrium sedimentation experiments were performed using a Beckman ProteomeLab XL-A analytical ultracentrifuge in 20 mm sodium citrate buffer, pH 5.5, containing 200 mm NaCl, at 20 °C. Absorbances of API5 samples were measured at 235, 240, and 280 nm using a two-sector cell at two different speeds (12,000 and 16,000 rpm) and two different concentrations (4.90 and 9.80 μm) with a loading volume of 180 μl. The calculated partial specific volumes at 20 °C were 0.7452 and 0.7416 cm3/g for API5ΔC and full-length API5, respectively. The buffer density was 1.01424 g/cm3. For mathematical modeling using non-linear least-squares curve fitting, the fitting function for homogeneous models was used, as described elsewhere (32). The model was selected by examining the weighted sum or square values and weighted root mean square deviation (r.m.s.d.) values.

Cell Viability Test

Jurkat cells were grown in RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (WelGENE). Transient transfection was performed with Lipofectamine LTX and Plus Reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 2.3 × 105 Jurkat cells were seeded in the medium onto a 24-well plate. After 1 h, the cells in each well were transfected with 0.6 μg of each DNA construct (full-length API5 wild type, K251R, K251Q, and K251A, respectively). After 3 h, the serum-free medium was exchanged with RPMI1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum to stabilize the transfected cells. After an additional 12-h incubation, the culture medium was exchanged with serum-free RPMI 1640 to perform a starvation test. Following a 48-h incubation, the cell viability in each well was determined using a Presto cell proliferation assay kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blotting

To monitor the oligomerization state of API5 in cells, full-length HA-API5 and 3×FLAG-API5 were co-transfected into HeLa cells and immunoprecipitated. Whole cell lysates prepared in lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate), were used for immunoprecipitation. Each lysate was mixed with a binding buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, and 1 mm EDTA) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktails (Roche Applied Science). The mixture was incubated overnight at 4 °C with antibodies (diluted 1:100). A/G-agarose beads were then added, incubated at 4 °C for 3 h, and washed four times with the binding buffer. The immune complex was released from the beads by boiling in sample buffer and was visualized by Western blotting. Western blotting was carried out using established protocols. The primary antibodies used were anti-HA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-FLAG (Cell Signaling Technologies), and anti-β-actin (Abcam).

To test protein stability in cells, full-length wild type API5 or mutants API5 (K251R and K251Q) was transfected into HeLa cells. At 22 h after transfection, the cells were treated with 10 μg/ml of cycloheximide for 4 h. Then, the cells were collected, and protein levels were analyzed by Western blotting. For the deacetylase inhibition experiments, suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid was pretreated for 20 h to the wild type API5-transfected HeLa cells before cycloheximide treatment.

RESULTS

Structure Determination and Overall Structure

We obtained crystals of full-length and trypsin-treated API5. However, only the crystals of trypsin-treated API5 were suitable for structure determination. From N-terminal amino acid sequencing and MALDI-TOF analysis, we found that the N-terminal fusion tag and ∼50 amino acid residues at the C-terminal of recombinant API5 were removed by trypsin and that the trypsin-treated form of API5 corresponded to residues 1–454. The crystal structure of API5ΔC was solved by multiwavelength anomalous dispersion and refined to 2.50 and 2.60 Å resolution for wild type and K251Q (acetylation mimic) mutant structures, respectively. The refined models of wild type and K251Q mutant exhibited working and free R-values of 21.6 and 24.2%, and 21.3 and 25.0%, respectively, with good stereochemistry (Table 1). One subunit of API5ΔC was found to be present in the asymmetric unit of the crystal. The structures of wild type and K251Q mutant are highly similar to each other, with an r.m.s.d. of 0.32 Å for 424 Cα atom pairs (supplemental Fig. S1).

TABLE 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Selenomethionine 1 | Selenomethionine 2 | Wild type | K251Q | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||||||

| X-ray source | PLS-4A | PLS-6C | PLS-6C | PF-BL1A | ||

| Space group | P212121 (Native cell parameters, a = 46.42, b = 88.61, and c = 136.29 Å; α = β = γ = 90°) | |||||

| Data set | Selenium (peak) | Selenium (edge) | Selenium (peak) | Selenium (edge) | Native | Native |

| Resolution (Å)a | 50.0-3.10 (3.21-3.10) | 50.0-3.10 (3.21-3.10) | 50.0-3.60 (3.73-3.60) | 50.0-3.50 (3.63-3.50) | 50.0-2.50 (2.59-2.50) | 50.0-2.60 (2.64-2.60) |

| Redundancya | 7.9 (8.1) | 7.9 (8.1) | 10.3 (8.6) | 7.8 (7.0) | 4.0 (3.0) | 6.7 (6.3) |

| Completeness (%)a | 99.4 (100.0) | 99.5 (100.0) | 99.9 (99.3) | 99.8 (98.9) | 94.1 (87.4) | 99.3 (99.1) |

| 〈I〉/〈σI〉a | 50.7 (6.7) | 49.5 (5.9) | 32 (4.7) | 31.8 (3.9) | 21.8 (2.2) | 39.3 (3.8) |

| Rmerge (%)a | 6.5 (34.9) | 5.8 (39.4) | 12.8 (49.7) | 10.4 (51.0) | 7.5 (42.1) | 7.7 (60.8) |

| Phasing | ||||||

| No. of Se sites | 5 | 6 | ||||

| Figure of merit (before/after RESOLVE) | 0.61/0.76 | |||||

| Refinement | ||||||

| Resolution (Å) | 50.0-2.50 | 50.0-2.60 | ||||

| No. of reflections | 18,082 | 17,022 | ||||

| Rwork/Rfree (%) | 21.6/24.2 | 21.3/25.0 | ||||

| No. of atoms (protein/water) | 3,389/119 | 3,382/60 | ||||

| Average B-factors (protein/water) (Å2) | 47.7/46.4 | 59.2/49.9 | ||||

| r.m.s.d. from ideal geometry (bond lengths/bond angles) | 0.010 Å/1.202° | 0.011 Å/1.337° | ||||

| r.m.s. Z-scores (Bond lengths/bond angles)b | 0.488/0.544 | 0.546/0.610 | ||||

| Ramachandran plot (%)c | ||||||

| Favored | 95.18 | 95.17 | ||||

| Outliers | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||

| Rotamer outliers (%)c | 0.53 | 0.79 | ||||

| PDB code | 3U0R | 3V6A | ||||

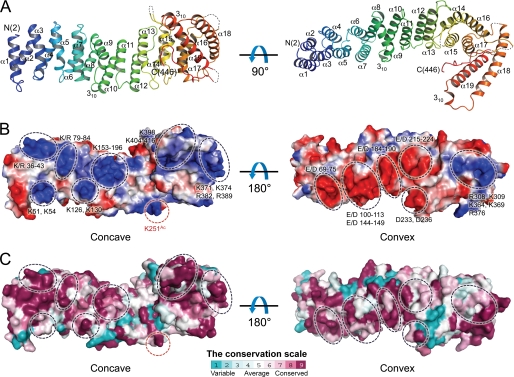

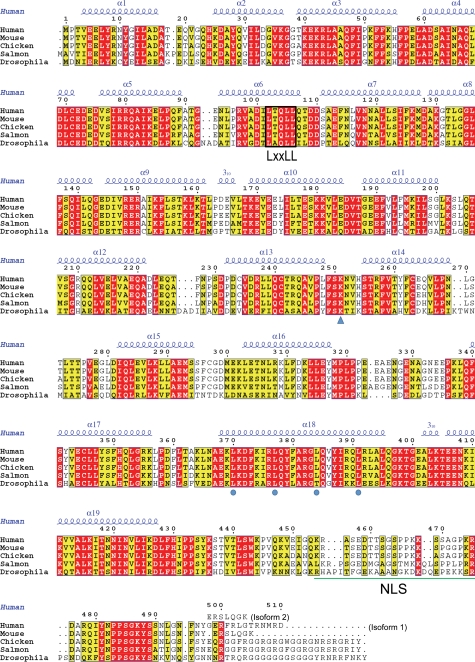

The API5ΔC monomer presented an elongated, all α-helical repeat structure, forming a right-handed superhelix with approximate dimensions of 100 × 35 × 50 Å (Fig. 1A). It consisted of 19 α-helices (α1–α19) and two 310 helices. Each helix was observed to be paired with its neighboring helix to form an antiparallel helix pair. Residues 277–278, 322–335, 365–366, 430–431, and 447–454, as well as the four extra N-terminal residues (Gly-Ser-His-Met), artificially added by cloning into pET-28b, were disordered in the crystal. The C-terminal region of API5 (residues 455–504), which contains a nuclear localization signal (Fig. 2) between residues 454–475 and is predicted to be disordered by IUPRED (33), was readily removed by trypsin. Additionally, an electron density map calculated using low resolution (∼6 Å) x-ray diffraction data from full-length API5 did not show this C-terminal region, supporting its hypothesized flexibility (data not shown). Several positively charged patches were found on the concave surface of the API5ΔC protein, whereas mainly negatively charged residues were positioned on the convex side (Fig. 1B). The positively or negatively charged patches were well conserved in various species (Fig. 1C). Basic patches were also found near the putative leucine zipper region (heptad leucine repeat). However, a basic DNA binding region typically followed by a leucine zipper of other leucine repeat proteins, was not found to be present in API5 (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 1.

The overall structural representation of API5. A, the ribbon diagram of API5ΔC reveals its elongated, all α-helical structure. B, surface charge properties of API5ΔC. The concave region of API5 is highly positively charged, whereas the convex region is negatively charged. The acidic and basic residues in the surface are denoted. Lys-251, shown using red dashed circles, is solvent-exposed, allowing access by acetyltransferases or deacetylases. C, surface representation colored by amino acid sequence conservation. Surface conservation was generated using ConSurf (57).

FIGURE 2.

Amino acid sequence alignment of API5 homologs from different species. The LxxLL motif is marked with a black box. The conserved leucine residues of the heptad leucine repeat are marked by blue circles, and the acetylation site Lys-251 is marked by a blue triangle. The LxxLL motif and nuclear localization signal (NLS) sequence are marked. The amino acid sequence for isoform 2 of human API5, which was used in this study, is also denoted above the sequence. The figure was prepared using ESPript.

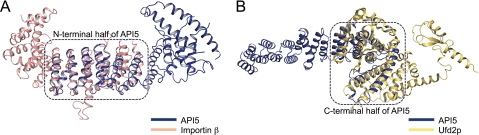

Searches using the DALI server were carried out to identify structurally similar proteins (34). Because the structure of API5ΔC can be divided into two regions, DALI searches were performed separately for the N-terminal half (α1-α11) and the C-terminal half (α12–α19). The N-terminal half of API5 structurally aligns with the HEAT repeat regions of importin β (PDB code 1O6P, Z-score = 13.1; r.m.s.d., 4.7 Å for 190 structurally aligned residues), the TOG2 domain of Msps (PDB code 2QK2, Z-score = 12.2; r.m.s.d. = 4.5 Å for 176 structurally aligned residues), and protein phosphatase 2A (PDB code 2C5W, Z-score = 11.8, r.m.s.d. = 1.8 Å for 87 structurally aligned residues). Although the sequence identities between the structurally aligned regions and API5 were only 10–12%, the overall folds were quite similar. The C-terminal half of API5 is structurally similar to the core region of the U-box-containing ubiquitin ligase E4 protein Ufd2p (PDB code 2QIZ, residues 461–747). The Z-score and r.m.s.d. values for the aligned 195 amino acid pairs were 8.3 and 4.4 Å, respectively. The amino acid sequences were also quite different between API5 and Ufd2p (lower than 11% sequence identity), although the three-dimensional structures were quite similar, including the characteristic long helix pair (α18-α19). The second most similar protein to the C-terminal half of API5 was p120 catenin (PDB code 3L6Y, Z-score = 7.7, r.m.s.d. = 3.3 Å for the aligned 152 amino acid pairs). Ufd2p and p120 catenin have been classified as ARM-like repeat proteins. These results indicate that the N-terminal half of API5 adopts the characteristic HEAT repeat structure, which is composed of pairs of antiparallel helices, whereas the C-terminal half of API5 shows an ARM-like repeat structure. Superposition of API5 and the structurally similar protein is shown in Fig. 3. The interhelix turns between antiparallel helices are relatively short (between two and four residues) in the HEAT repeats of API5, resulting in a tight fold of the repeat structure, whereas the turns in the ARM-like repeat regions are longer (6 to 22 residues) (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 3.

The structural similarity between API5 and HEAT and ARM motif-containing proteins. A, the N-terminal half of API5 is structurally similar to importin β (salmon). B, the C-terminal-half of API5 is structurally similar to the core domain of Ufd2p (yellow). Superimposed regions are indicated by dashed boxes.

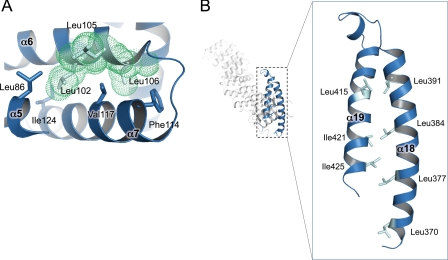

The amino acid sequence of API5 contains an LxxLL motif (16). The LxxLL motif forms a short amphipathic α-helix and is usually found in nuclear receptor-cofactor interaction regions (35, 36). The LxxLL motif in API5 is positioned in α6 (Figs. 1A, 2, 4A). However, the three leucine residues in this motif are not located on the surface of the protein and likely do not play any role in protein-protein interactions. Instead, because they are located in the interior of the protein, they may contribute to the stability of the HEAT repeat by forming hydrophobic interactions with neighboring α-helices. Leu-102 interacts with Ala-120, Ile-124 of α7, and Leu-86 of α5. Leu-105 and Leu-106 interact with Val-117 and Phe-114 of α7, respectively (Fig. 4A). This finding is consistent with a previous report indicating that the replacement of these conserved leucine residues does not abolish FGF-2 binding (16).

FIGURE 4.

Detailed motif/domain structure of API5. A, LxxLL motif and interacting residues. The leucine residues interact with hydrophobic residues on the adjacent helices and are involved in stabilization of the repeated structure. B, heptad leucine repeat region. α18 is covered by α19 from the same subunit and does not form a typical leucine zipper. The leucine residues of the heptad repeat and hydrophobic residues on α19 are close to each other (shown in a stick representation).

Assessment of API5 Oligomerization and Heptad Leucine Repeat Region

The heptad repeat of leucine residues between residues 370 and 391 in API5 has been predicted to be a leucine zipper without a basic DNA-binding region (14). Therefore, it has been suggested that API5 may form a dimer in solution. However, the crystal structure of API5ΔC indicates that API5 is monomeric and that the putative leucine zipper (α18) does not interact with the corresponding helix of another subunit. Instead, it interacts with α19 of the same subunit (Figs. 1A and 4B). Two sets of low resolution data were collected from crystals of full-length API5 (∼6 Å resolution) or API5ΔC (∼4 Å resolution) grown under different crystallization conditions. Protein molecules positioned by the molecular replacement method indicate that both API5 and API5ΔC are monomeric under different crystallization conditions (data not shown).

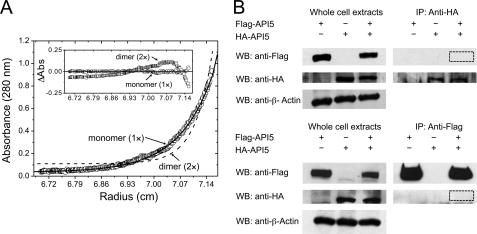

Because the oligomeric state of API5 in the crystal was found to be different from the predicted dimeric state, the relevant oligomeric state of API5 in solution was further investigated by analytical ultracentrifugation (Fig. 5A). The estimated molecular mass (54,949 Da (±234)) agreed with the calculated molecular mass for an API5ΔC monomer, including the fusion tag (53,521 Da). The full-length API5 protein was also found to be monomeric, indicating minimal effects of the C-terminal truncation on the oligomeric structure of API5. The estimated molecular mass of full-length API5 (60,129 Da (±1,164)) agreed with the calculated molecular mass for the full-length API5 monomer including the fusion tag (58,934 Da).

FIGURE 5.

Oligomerization of API5. A, analytical ultracentrifugation analysis. Distributions of the residuals according to both a monomer (1×, circle) and a dimer (2×, square) models. The random distributions of residuals for the monomer (1×) model indicate that API5ΔC exists as a homogeneous monomer in solution. B, immunoprecipitation (IP) and Western blot (WB) analysis with anti-FLAG and anti-HA API5. No interaction was found between FLAG-API5 and HA-API5, ruling out the possibility of API5 homodimerization.

Additionally, we transiently expressed HA-tagged and 3×FLAG-tagged full-length API5 in HeLa cells and performed immunoprecipitation experiments (Fig. 5B). No interaction was found between HA-tagged API5 and 3×FLAG-tagged API5. This result shows that API5 does not homodimerize in cells. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that API5 heterodimerize with other leucine zipper-containing proteins under specific cellular conditions. Taken together, we unexpectedly discovered that API5 is monomeric and that its putative leucine zipper helix (α18) does not participate in dimerization. Three of the four leucine residues in the heptad repeat (Leu-377, Leu-384, and Leu-391) exhibit hydrophobic interactions with hydrophobic residues in α19; Leu-377 and Leu-384 interact with Ile-425 and Ile-421, respectively, and Leu-391 is close to Leu-415 (Fig. 4B). Leu-370 does not interact with other residues.

Lysine Acetylation and Its Effect on Cancer Cells

A global mass analysis showed that Lys-251 of API5 is acetylated in cells (37). Amino acid sequence alignment showed that this lysine residue is strictly conserved across a number of species (Fig. 2). Lys-251 is positioned in a loop between α13 and α14, which is extended from the protein (Fig. 1B). This finding suggests that acetyltransferases or deacetylases can easily access this residue.

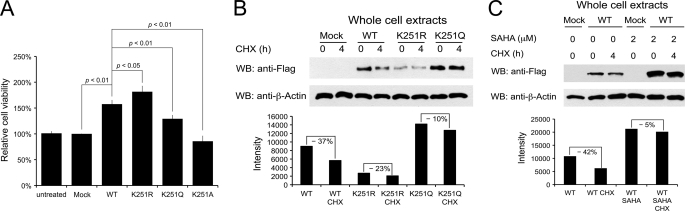

API5 plays important roles in the inhibition of cell death under serum deprivation conditions (14, 15). Therefore, we tested whether lysine acetylation affected cell viability 48 h after the transient transfection under serum deprivation conditions (Fig. 6A). We made an acetylation-deficient, a constitutive acetylation mimic, and an uncharged mutant (K251R, K251Q, and K251A, respectively) (37, 38). Wild type API5 inhibited cell death by serum starvation compared with untreated or control vector-transfected cells. The K251R mutant exhibited even higher cell viability. However, the K251Q mutant did not inhibit apoptosis efficiently compared with the wild type API5 and the K251R mutant. The K251A mutant did not have anti-apoptotic function. This result means that the inhibition of apoptosis by API5 can be negatively regulated by Lys-251 acetylation. We tried to find the structural basis for anti-apoptotic function by lysine acetylation from the structure of K251Q mutant. However, no significant structural differences were found (supplemental Fig. S1).

FIGURE 6.

Effects of API5 acetylation at Lys-251. Wild type API5, an acetylation-deficient mutant (K251R), a constitutive acetylation mimic mutant (K251Q), and an uncharged mutant (K251A) were transiently expressed. A, effects on cell viability under conditions of serum deprivation. The K251Q and K251A mutants do not inhibit apoptosis efficiently. B, effects of Lys-251 acetylation on protein stability. Cycloheximide (CHX) treatment was used to inhibit protein synthesis, and Western blot (WB)/normalized densitiometry analysis was performed to monitor protein stability in cells. C, effects on protein stability when deacetylase inhibitor, suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA), was co-treated with cycloheximide to wild type API5-transfected cells.

We also tested whether lysine acetylation affected API5 protein stability. After 22 h of transfection, protein synthesis was stopped by treatment with cycloheximide, and the protein level was monitored by Western blot analysis after 4 h of treatment. The K251Q mutant was more stable than the wild type API5 and the K251R mutant (Fig. 6B). Similar results were also found when deacetylase inhibitor suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid was treated (Fig. 6C). Therefore, we conclude that the regulation of API5 function by lysine acetylation may occur via effects on protein stability. However, we could not detect any ubiquitination of API5 at Lys-251, suggesting the proteasome-independent degradation pathway (data not shown).

The cellular localization of API5 also was monitored to determine whether lysine acetylation affected the nuclear transport of API5. All of the wild type and mutants API5 (K251R and K251Q) were observed in the cell nuclei, implying that lysine acetylation did not affect cellular localization (supplemental Fig. S2). The analysis of the API5 and FGF-2 interaction detected by in vitro immunoprecipitation method using the purified recombinant API5 and FGF-2 did not show any significant FGF-2 binding differences between wild type and mutant API5s (supplemental Fig. S3).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we determined the crystal structure of human API5 and found that API5 contains protein-protein interaction modules, such as HEAT and ARM repeats (Fig. 1A). Different types of helix repeat, including HEAT, ARM, ankyrin, tetratrico peptide, and leucine-rich variant repeats, have been found in many proteins and have diverse functional roles in mediating protein-protein interactions (39). The elongated structure of API5 is well suited for interactions with multiple binding partners, similar to the roles of other repeat proteins (40).

The structures of various HEAT and ARM repeat-containing proteins in complexes with other proteins have been elucidated. Ran-importin β, protein phosphatase 2 holoenzyme, and the Cand1-Cul1-Roc1 complex are good examples of HEAT repeat complex structures (importin β, the A subunit of protein phosphatase 2 holoenzyme, and Cand1 are HEAT repeat-containing proteins) (41–43). Several crystal structures of the ARM repeat-containing protein (e.g. β-catenin) in complex with the interacting proteins have been determined (44–47). In many curved HEAT repeat proteins, protein-protein interactions are mediated by the concave surface of the protein, regardless of the surface charge distribution, and the protein-protein interaction surface involving the ARM repeat proteins usually span the entire range of the repeat. The charged concave or convex side of the API5 is well conserved across a number of species. This suggests that binding partners can bind to these regions.

It has been reported that high molecular mass FGF-2 interacts with API5 in the nucleus, and immunoprecipitation results suggest that two separate regions corresponding to three helices (α6 and α15–α16) of API5 are important for FGF-2 binding (16). The α6 is exposed to the convex surface of API5, and α15-α16 are exposed on both the concave and convex surfaces. Analyses of surface properties indicated that the convex side of API5 is highly negatively charged, whereas FGF-2 is highly positively charged (Fig. 1B). Although hydrophobic interactions may also be important for binding, we predict that the positively charged high molecular mass FGF-2 likely binds to the negatively charged convex surface of API5, as determined from previous immunoprecipitation results and surface electrostatic potential (16).

It has been reported that API5 binds to Acinus and protects it from cleavage by caspase-3, resulting in an inhibition of apoptosis (23). Acinus has been identified as a component of an ASAP (apoptosis and splicing-associated protein) complex and an exon junction complex (EJC) (48, 49). API5 and Acinus interact with each other through the heptad leucine repeat region of API5, which seems to be important for API5 function and may therefore represent a potential therapeutic target for anti-cancer drugs (23). Mutation of leucine residues (Leu-384 and Leu-391) in the heptad leucine repeat region abrogates the anti-apoptotic effects of API5 (14, 23). Because Leu-384 and Leu-391 contribute to hydrophobic interactions with other hydrophobic residues in α19, mutation of these residues might cause a distortion of the local structure of API5, thus affecting protein-protein interactions, rather than inhibiting the dimerization. Because API5 is monomeric and the heptad leucine repeat of API5 is structurally distinct from that of other leucine zippers, API5 provides a unique opportunity for anti-cancer drug discovery through targeting of this region. However, further studies and target validation will be required to develop API5-targeted inhibitors.

It is known that Nϵ-acetylation at lysine residues affects DNA binding, protein-protein interaction, cellular localization, ubiquitination, phosphorylation, and protein stability (50). A global analysis of lysine acetylation using high resolution mass spectrometry showed that Lys-251 of API5 is acetylated (37). Our data clearly showed that lysine acetylation impacts cell survival under serum deprivation conditions, suggesting an inhibition of function. Therefore, we conclude that API5 function is negatively regulated by acetylation at Lys-251. Inhibition of function via acetylation has also been found in HSP90 and 14-3-3 proteins (37, 38). We determined that lysine acetylation affects API5 protein stability, which has been found for p53 as well (51). However, we could not detect ubiquitination of API5, and a detailed mechanism for degradation of API5 has not yet been established. We predict that API5 may be readily acetylated by an acetyltransferase(s) after protein synthesis and that API5 exists in an inactive and stable state in cells until certain deacetylases can activate API5 through deacetylation. However, activated API5 appears to be unstable and easily degraded in cells. Although the acetyltrasferases or deacetylases that act on API5 have not yet been identified, these enzymes are likely to be important regulatory factors for the function of API5. Additionally, we predict that certain histone deacetylase inhibitors may also be effective in regulating API5 function. We could not found any significant differences in API5-FGF-2 interaction and cellular localization from the lysine acetylation mimic/deficient mutants. However, it is still possible that lysine acetylation of API5 will affect protein-protein interactions between API5 and other API5 interacting partners to induce anti-apoptosis function. We can easily predict that lysine acetylation can inhibit the binding of API5 to its binding partners for its proper function. However, it is also quite likely that lysine acetylated API5 can be recognized by new binding partners, such as bromodomain containing proteins, resulting in a negative regulation of apoptosis (52). Hence, further investigations are needed to elucidate the detailed mechanism for functional regulation by lysine acetylation.

A recent report suggested that the rice API5 homolog interacts with two DEAD-box RNA helicases AIP1/2 (API5-interacting protein 1/2), thereby regulating programmed cell death in the tapetum during the development of male gametophytes (13). The human homolog of rice AIP1/2 is the ATP-dependent RNA helicases UAP56. This protein is involved in pre-mRNA splicing and mRNA nuclear export (53). Interestingly, hUAP56 is a component of large protein complexes, such as the EJC or TREX (Transcription-export) complex (54, 55). Particularly, Acinus, another API5 binding protein, is also a component of EJC complex, implying the functional link between API5 and EJC complex. Another study showed that API5 interacts with the chromatin-remodeling enzyme ALC1 (also known as CHD1L), which is a member of the SNF2 family containing a DEAH box helicase domain (24). ALC1 plays important roles in promoting cell proliferation and inhibits apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma (56). ALC1 also has been shown to interact with various DNA repair proteins such as DNA-PKCs, Ku, PARP1 (Poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase 1), XRCC (X-ray repair cross-complementing protein), and APLF (Aprataxin PNK-like factor) as well as API5 (24), implying that API5 may also mediate protein-protein interactions in DNA damage response protein complexes. Taken together, the interactions between API5 and EJC component proteins and chromatin-remodeling enzyme such as ALC1 suggest the possible roles of API5 at a transcriptional level.

In conclusion, the protein structure obtained in this study reveals that API5 possesses protein-protein interaction modules that likely mediate interactions with partners such as high molecular mass FGF-2, Acinus, AIP1/2, and ALC1. These interacting proteins are usually components of multiprotein complexes. Therefore, API5 may serve as a scaffold for multiprotein complexes, and the identification of interacting protein partners will help to illuminate the functional roles of API5. Furthermore, since we show that the API5 function is regulated by lysine acetylation, identifying the lysine acetyltransferases and deacetylases that act on API5 should also yield a better understanding of the mechanisms that regulate API5 function.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff at the Pohang Light Source (beamlines 4A and 6C) and the Photon Factory (BL-1A) for assistance with synchrotron data collection.

This work was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology Grant 2010-0020993 (to B. I. L.).

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 3U0R and 3V6A) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

This article contains supplemental “Materials and Methods” and Figs. S1–S3.

- IAP

- inhibitor of apoptosis

- r.m.s.d.

- root mean square deviation

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank

- EJC

- exon junction complex.

REFERENCES

- 1. Meier P., Finch A., Evan G. (2000) Apoptosis in development. Nature 407, 796–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Danial N. N., Korsmeyer S. J. (2004) Cell death: Critical control points. Cell 116, 205–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Igney F. H., Krammer P. H. (2002) Death and anti-death: Tumor resistance to apoptosis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2, 277–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yang S. Y., Sales K. M., Fuller B., Seifalian A. M., Winslet M. C. (2009) Apoptosis and colorectal cancer: Implications for therapy. Trends Mol. Med. 15, 225–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Altieri D. C. (2010) Survivin and IAP proteins in cell death mechanisms. Biochem. J. 430, 199–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ghobrial I. M., Witzig T. E., Adjei A. A. (2005) Targeting apoptosis pathways in cancer therapy. CA Cancer J. Clin. 55, 178–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Alnemri E. S., Livingston D. J., Nicholson D. W., Salvesen G., Thornberry N. A., Wong W. W., Yuan J. (1996) Human ICE/CED-3 protease nomenclature. Cell 87, 171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wyllie A. H., Kerr J. F., Currie A. R. (1980) Cell death: The significance of apoptosis. Int. Rev. Cytol. 68, 251–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kasibhatla S., Tseng B. (2003) Why target apoptosis in cancer treatment? Mol. Cancer Ther. 2, 573–580 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Salvesen G. S., Duckett C. S. (2002) IAP proteins: Blocking the road to death's door. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 401–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Srinivasula S. M., Ashwell J. D. (2008) IAPs: What's in a name? Mol. Cell 30, 123–135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gyrd-Hansen M., Meier P. (2010) IAPs: From caspase inhibitors to modulators of NF-κB, inflammation, and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10, 561–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Li X., Gao X., Wei Y., Deng L., Ouyang Y., Chen G., Li X., Zhang Q., Wu C. (2011) Rice APOPTOSIS INHIBITOR5 coupled with two DEAD-box adenosine 5′-triphosphate-dependent RNA helicases regulates tapetum degeneration. Plant Cell 23, 1416–1434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tewari M., Yu M., Ross B., Dean C., Giordano A., Rubin R. (1997) AAC-11, a novel cDNA that inhibits apoptosis after growth factor withdrawal. Cancer Res. 57, 4063–4069 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim J. W., Cho H. S., Kim J. H., Hur S. Y., Kim T. E., Lee J. M., Kim I. K., Namkoong S. E. (2000) AAC-11 overexpression induces invasion and protects cervical cancer cells from apoptosis. Lab. Invest. 80, 587–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Van den Berghe L., Laurell H., Huez I., Zanibellato C., Prats H., Bugler B. (2000) FIF (fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2)-interacting-factor), a nuclear putatively antiapoptotic factor, interacts specifically with FGF-2. Mol. Endocrinol. 14, 1709–1724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sasaki H., Moriyama S., Yukiue H., Kobayashi Y., Nakashima Y., Kaji M., Fukai I., Kiriyama M., Yamakawa Y., Fujii Y. (2001) Expression of the antiapoptosis gene, AAC-11, as a prognosis marker in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 34, 53–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Clegg N., Ferguson C., True L. D., Arnold H., Moorman A., Quinn J. E., Vessella R. L., Nelson P. S. (2003) Molecular characterization of prostatic small-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. Prostate 55, 55–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Krejci P., Pejchalova K., Rosenbloom B. E., Rosenfelt F. P., Tran E. L., Laurell H., Wilcox W. R. (2007) The antiapoptotic protein Api5 and its partner, high molecular weight FGF2, are up-regulated in B cell chronic lymphoid leukemia. J. Leukoc. Biol. 82, 1363–1364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang Z., Liu H., Liu B., Ma W., Xue X., Chen J., Zhou Q. (2010) Gene expression levels of CSNK1A1 and AAC-11, but not NME1, in tumor tissues as prognostic factors in NSCLC patients. Med. Sci. Monit. 16, CR357–364 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Morris E. J., Michaud W. A., Ji J. Y., Moon N. S., Rocco J. W., Dyson N. J. (2006) Functional identification of Api5 as a suppressor of E2F-dependent apoptosis in vivo. PLoS Genet. 2, e196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ren K., Zhang W., Shi Y., Gong J. (2010) Pim-2 activates API-5 to inhibit the apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells through NF-κB pathway. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 16, 229–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rigou P., Piddubnyak V., Faye A., Rain J. C., Michel L., Calvo F., Poyet J. L. (2009) The antiapoptotic protein AAC-11 interacts with and regulates Acinus-mediated DNA fragmentation. EMBO J. 28, 1576–1588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ahel D., Horejsí Z., Wiechens N., Polo S. E., Garcia-Wilson E., Ahel I., Flynn H., Skehel M., West S. C., Jackson S. P., Owen-Hughes T., Boulton S. J. (2009) Poly(ADP-ribose)-dependent regulation of DNA repair by the chromatin remodeling enzyme ALC1. Science 325, 1240–1243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Otwinowski Z., Minor W. (1997) Processing of x-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods in Enzymology 276, 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Terwilliger T. C., Berendzen J. (1999) Automated MAD and MIR structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 55, 849–861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Adams P. D., Afonine P. V., Bunkóczi G., Chen V. B., Davis I. W., Echols N., Headd J. J., Hung L. W., Kapral G. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Oeffner R., Read R. J., Richardson D. C., Richardson J. S., Terwilliger T. C., Zwart P. H. (2010) PHENIX: A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Murshudov G. N., Vagin A. A., Dodson E. J. (1997) Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53, 240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brünger A. T. (1992) Free R value: A novel statistical quantity for assessing the accuracy of crystal structures. Nature 355, 472–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chen V. B., Arendall W. B., 3rd, Headd J. J., Keedy D. A., Immormino R. M., Kapral G. J., Murray L. W., Richardson J. S., Richardson D. C. (2010) MolProbity: All-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 12–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jung W. S., Hong C. K., Lee S., Kim C. S., Kim S. J., Kim S. I., Rhee S. (2007) Structural and functional insights into intramolecular fructosyl transfer by inulin fructotransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 8414–8423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dosztányi Z., Csizmok V., Tompa P., Simon I. (2005) IUPred: Web server for the prediction of intrinsically unstructured regions of proteins based on estimated energy content. Bioinformatics 21, 3433–3434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Holm L., Rosenström P. (2010) Dali server: Conservation mapping in 3D. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, W545–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Heery D. M., Kalkhoven E., Hoare S., Parker M. G. (1997) A signature motif in transcriptional co-activators mediates binding to nuclear receptors. Nature 387, 733–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Plevin M. J., Mills M. M., Ikura M. (2005) The LxxLL motif: A multifunctional binding sequence in transcriptional regulation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 30, 66–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Choudhary C., Kumar C., Gnad F., Nielsen M. L., Rehman M., Walther T. C., Olsen J. V., Mann M. (2009) Lysine acetylation targets protein complexes and co-regulates major cellular functions. Science 325, 834–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Scroggins B. T., Robzyk K., Wang D., Marcu M. G., Tsutsumi S., Beebe K., Cotter R. J., Felts S., Toft D., Karnitz L., Rosen N., Neckers L. (2007) An acetylation site in the middle domain of Hsp90 regulates chaperone function. Mol. Cell 25, 151–159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Groves M. R., Barford D. (1999) Topological characteristics of helical repeat proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 9, 383–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tu D., Li W., Ye Y., Brunger A. T. (2007) Structure and function of the yeast U-box-containing ubiquitin ligase Ufd2p. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 15599–15606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Vetter I. R., Arndt A., Kutay U., Görlich D., Wittinghofer A. (1999) Structural view of the Ran-Importin β interaction at 2.3 A resolution. Cell 97, 635–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cho U. S., Xu W. (2007) Crystal structure of a protein phosphatase 2A heterotrimeric holoenzyme. Nature 445, 53–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Goldenberg S. J., Cascio T. C., Shumway S. D., Garbutt K. C., Liu J., Xiong Y., Zheng N. (2004) Structure of the Cand1-Cul1-Roc1 complex reveals regulatory mechanisms for the assembly of the multisubunit cullin-dependent ubiquitin ligases. Cell 119, 517–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Choi H. J., Gross J. C., Pokutta S., Weis W. I. (2009) Interactions of plakoglobin and β-catenin with desmosomal cadherins: Basis of selective exclusion of α- and β-catenin from desmosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 31776–31788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sampietro J., Dahlberg C. L., Cho U. S., Hinds T. R., Kimelman D., Xu W. (2006) Crystal structure of a β-catenin-BCL9-Tcf4 complex. Mol. Cell 24, 293–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Xing Y., Clements W. K., Kimelman D., Xu W. (2003) Crystal structure of a β-catenin-axin complex suggests a mechanism for the β-catenin destruction complex. Genes Dev. 17, 2753–2764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Huber A. H., Weis W. I. (2001) The structure of the β-catenin-E-cadherin complex and the molecular basis of diverse ligand recognition by β-catenin. Cell 105, 391–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Schwerk C., Prasad J., Degenhardt K., Erdjument-Bromage H., White E., Tempst P., Kidd V. J., Manley J. L., Lahti J. M., Reinberg D. (2003) ASAP, a novel protein complex involved in RNA processing and apoptosis. Mol. Cell Biol. 23, 2981–2990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tange T. Ø., Shibuya T., Jurica M. S., Moore M. J. (2005) Biochemical analysis of the EJC reveals two new factors and a stable tetrameric protein core. RNA 11, 1869–1883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yang X. J. (2004) Lysine acetylation and the bromodomain: A new partnership for signaling. Bioessays 26, 1076–1087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yang X. J., Seto E. (2008) Lysine acetylation: Codified cross-talk with other post-translational modifications. Mol. Cell 31, 449–461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zeng L., Zhou M. M. (2002) Bromodomain: An acetyllysine binding domain. FEBS Lett. 513, 124–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shen H. (2009) UAP56, a key player with surprisingly diverse roles in pre-mRNA splicing and nuclear export. BMB Rep 42, 185–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Strässer K., Masuda S., Mason P., Pfannstiel J., Oppizzi M., Rodriguez-Navarro S., Rondón A. G., Aguilera A., Struhl K., Reed R., Hurt E. (2002) TREX is a conserved complex coupling transcription with messenger RNA export. Nature 417, 304–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Le Hir H., Andersen G. R. (2008) Structural insights into the exon junction complex. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 18, 112–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ma N. F., Hu L., Fung J. M., Xie D., Zheng B. J., Chen L., Tang D. J., Fu L., Wu Z., Chen M., Fang Y., Guan X. Y. (2008) Isolation and characterization of a novel oncogene, amplified in liver cancer 1, within a commonly amplified region at 1q21 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 47, 503–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ashkenazy H., Erez E., Martz E., Pupko T., Ben-Tal N. (2010) ConSurf 2010: Calculating evolutionary conservation in sequence and structure of proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, W529–533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.