Background: Extracellular acidification is a feature of inflammation loci in which apoptotic cell clearance is necessary for inflammation resolution.

Results: Low pH increases stabilin-1 expression and stabilin-1-mediated phagocytosis in macrophages.

Conclusion: Extracellular acidification up-regulates stabilin-1 expression in macrophages, thereby modulating the phagocytic capacity of macrophages.

Significance: This study should help elucidate the molecular mechanism regarding stabilin-1 regulation and apoptotic cell clearance in acidic environments.

Keywords: Acidosis, Macrophages, Phagocytosis, Phosphatidylserine, Transcription Regulation, Ets-2, Stabilin-1

Abstract

Microenvironmental acidosis is a common feature of inflammatory loci, in which clearance of apoptotic cells is necessary for the resolution of inflammation. Although it is known that a low pH environment affects immune function, its effect on apoptotic cell clearance by macrophages has not been fully investigated. Here, we show that treatment of macrophages with low pH medium resulted in increased expression of stabilin-1 out of several receptors, which are known to be involved in PS-dependent removal of apoptotic cells. Reporter assays showed that the −120/−1 region of the mouse stabilin-1 promoter was a low pH-responsive region and provided evidence that extracellular low pH mediated transcriptional activation of stabilin-1 via Ets-2. Furthermore, extracellular low pH activated JNK, thereby inducing translocation of Ets-2 into the nucleus. When macrophages were preincubated with low pH medium, phagocytosis of phosphatidylserine-exposed red blood cells and phosphatidylserine-coated beads by macrophages was enhanced. Blockade of stabilin-1 in macrophages abolished the enhancement of phagocytic activity by low pH. Thus, our results demonstrate that a low pH microenvironment up-regulates stabilin-1 expression in macrophages, thereby modulating the phagocytic capacity of macrophages, and suggest roles for stabilin-1 and Ets-2 in the maintenance of tissue homeostasis by the immune system.

Introduction

Extracellular acidification is a feature associated with inflammation in several physiological and pathological situations, including the inflammation response against pathogens, autoimmune diseases, and tumors. Acidic microenvironments (pH 5.5–7.0) during inflammatory reactions against pathogens are the result of local acid production by anaerobic, glycolytic infiltrating neutrophils and macrophages, short chain fatty acid production by bacteria, and low oxygen tensions in inflammatory regions (1–5). Autoimmune processes such as those in rheumatoid arthritis and asthma are associated with the development of acidic microenvironments, with pH values ranging from 6.7 to 7.4 (6). Extracellular acidosis has also been observed in tumor microenvironments, where the extracellular pH ranges from 5.8 to 7.6 (7, 8).

The conditions with acidic microenvironments are associated with cell corpse clearance. During inflammation processes, the efficient removal of apoptotic cells is a key to the resolution of inflammation and crucial to the protection of normal healthy cells from harmful contents and debris from dying cells (9, 10). Inappropriate removal of cell corpses results in chronic inflammation or autoimmune responses. Macrophages mediate the clearance of apoptotic cells through the recognition of phosphatidylserine (PS)2 on the cell surface (11). Recognition of apoptotic cells by PS receptor on macrophages also induces the release of anti-inflammatory cytokines, thereby contributing to the resolution of inflammation (9). Although removal of inflammatory cells by macrophages is a key role in maintenance of tissue homeostasis during inflammation processes, little is known about the effect of low extracellular pH on the function of macrophages. Several studies suggest that extracellular acidification is correlated with the degree of reduction of the inflammatory response (12, 13). Therefore, a system should be developed that allows macrophages to efficiently remove apoptotic cells in an acidic microenvironment.

Stabilin-1 (also called FEEL-1 and CLEVER-1) is a type I transmembrane receptor with multiple functions (14). It was initially identified as a high molecular weight protein produced by sinusoidal endothelial cells. Stabilin-1 protein is expressed by cells specialized in the clearance of “unwanted self” and in the maintenance of tissue homeostasis, including different subsets of tissue macrophages as well as noncontinuous endothelial cells in the lymph nodes, liver, spleen, and bone marrow (15, 16). One of the major functions of stabilin-1 in macrophages is the clearance of exogenous non-self as well as unwanted self components present in the extracellular environment, including modified low density lipoproteins and advanced glycation end products (17–19). Recent studies reported that stabilin-1 mediates the internalization and clearance of secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine, a multifunctional regulator of tissue remodeling (20). In addition to functioning as a scavenger receptor, stabilin-1 in macrophages is involved in intracellular sorting and lysosomal delivery of stabilin-1-interacting chitinase-like protein and placental lactogen (21, 22). Recently, we demonstrated that stabilin-1 is a phagocytic receptor involved in PS-specific engulfment of apoptotic and aged cells in alternatively activated macrophages (23). Although stabilin-1 has multiple functions in macrophages and endothelial cells, transcriptional regulation of stabilin-1 expression is largely unknown. In this study, we present evidence that extracellular low pH induces stabilin-1 expression in macrophages, thereby increasing the phagocytic activity of macrophages.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Antibodies and Reagents

Goat polyclonal anti-stabilin-1 antibody (N-13) (for function blocking) was purchased from Santa Cruz. Rabbit polyclonal anti-stabilin-1 antibody (1bR1) (for immunostaining) was used as described previously (24). Anti-Ets-2 (for Western blotting), anti-Ets1/2 (for immunoprecipitation), anti-Ets-1, and anti-YY1 antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Anti-actin antibody was purchased from Sigma. Normal goat IgG and rabbit IgG were obtained from Chemicon. Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-goat IgG antibody and Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG were obtained from Molecular Probes. 1-oleoyl-2-[6-[(7-nitro-2–1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-yl)amino]hexanoyl]-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (NBD-PC) liver L-α-phosphatidylcholine (PC), and brain L-α-phosphatidylserine (PS) were purchased from Avanti-Polar Lipids. Specific MAPK inhibitors (PD98059, SB203580, and SP600125) were purchased from Calbiochem.

Cell Culture

Mouse peritoneal macrophages were isolated from C57BL6 mice 4 days after intraperitoneal injection of 3% Brewer thioglycollate medium (1 ml/mouse) and maintained in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% (v/v) FBS and antibiotics. Raw264.7 cells were grown in (high glucose) DMEM containing 10% FBS.

Quantitative Real Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from peritoneal macrophages and Raw264.7 cells using TRIzol reagent, in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). Reverse transcription was performed with Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Promega) using 2 μg of total RNA (Invitrogen) for 50 min at 42 °C, followed by 3 min at 95 °C. The resulting cDNA was diluted 2.5-fold and used to amplify PS-recognizing receptors (Tim-1, Tim-4, BAI1, stabilin-1, stabilin-2, CD14, and CD36) or β-actin as a control. Real time PCR amplification was carried out using SYBR green master mix (Roche Applied Science) in a LightCycler 480 (Roche Applied Science) as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min; 45 cycles of amplification with denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 58 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s; 1 cycle of melting curves at 95 °C for 5 s, 65 °C for 1 min, and 97 °C continuous; and a final cooling step at 40 °C for 30 s. All of the samples were run in triplicate. The quantitative RT-PCR results were analyzed using the comparative cycle threshold (CT) method as previously described (24). Primer sequences used were as follows: mouse Stab1 forward, 5′-TCT GAG TAT CAA TGC CAG CC-3′ and mouse Stab1 reverse, 5′-ATT TGA CCT TGA GGA CCC TC-3′; mouse Stab2 forward, 5′-TTG AAA CAC CTG ACT GAC CTG TCC-3′ and mouse Stab2 reverse, 5′-GGC GTT GAG GTC TCA TAC AAA G-3′; mouse Cd36 forward, 5′-GGT CTA TCT ACG CTG TGT TCG-3′ and mouse Cd36 reverse, 5′-ATC TAA GTA TGT CCT ATG CTC-3′; mouse Tim-1 forward, 5′-CAT CCC ATA CTC CTA CAG AC-3′ and mouse Tim-1 reverse, 5′-TTA GAG ACA CGG AAG GCA AC-3′; mouse Tim-4 forward, 5′-ATG ACC ACA TCT GTT CTC CC-3′ and mouse Tim-4 reverse, 5′-TTG AGG ACG CTG TCA CTA TC-3′; mouse Bai1 forward, 5′-CCT AAT CAC TCA CTC ACC CTC-3′ and mouse Bai1 reverse, 5′-TGC TTC TCT GGC TTG CTG TC-3′; and mouse Cd14 forward, 5′-ACT CGC TCA ATC TGT CTT TC-3′ and mouse Cd14 reverse, 5′-AAG CCA GAG TTC CTG ACA AG-3′. For analysis of mRNA stability, the cells were incubated in pH 7.4 or 6.8 medium for 4 h in the presence or absence of 10 μg/ml of actinomycin D.

Immunofluorescent Staining and Confocal Microscopy

Raw264.7 cells were incubated in low pH medium (pH 6.8) for 4 h, fixed in 3.7% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 5 min at room temperature, and then permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100. Nonspecific binding was minimized by incubating the cells in PBS containing 2% BSA for 1 h. After three washes with PBS, the slides were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with polyclonal anti-stabilin-1 antibody (1bR1) or rabbit IgG as an isotype-matched control. After three washes with PBS, Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Molecular Probes) was added, followed by incubation for 1 h at room temperature. The slides were then washed three times with PBS for 5 min each, stained with DAPI (Sigma), and mounted with Prolong Antifade (Molecular Probes). The slides were viewed with a Zeiss fluorescent microscope using Axioplan2 imaging.

Construction of Mouse Stabilin-1 Reporter Plasmids

The transcriptional start site of the mouse stabilin-1 gene was determined by 5′-rapid amplification of cDNA ends using cDNA from mouse spleen, in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen) (supplemental Fig. S1). A fragment corresponding to the mouse stabilin-1 promoter region (pStab1–978/+66) was amplified from mouse spleen genomic DNA by PCR using the following primers: forward primer, 5′-AAA AGG TAC CAT CAC AGC ACT TAG AAG-3′ and reverse primer, 5′-TTT TGG TAC CTT GCC TGA GTG GAG GTC-3′. The PCR product was cloned into the Asp718I-XhoI sites of the pGL3/basic vector (Promega). To generate 5′ deletion mutants of the mouse stabilin-1 promoter, PCR was performed using the same reverse primer and following forward primers: 5′-TTT TGG TAC CTT GCC TGA GTG GAG GTC-3′ (−653/+66); 5′-AAA AGG TAC CCC AAG TGA GGG ACG TCA C-3′ (−568/+66); 5′-AAA AGG TAC CGG CTG TCC AAC AAC CTC CTA G-3′ (−349/+66); 5′-AAA AGG TAC CCA GGG AGC AGC GTC CTG-3′ (−181/+66); 5′-AAA AGG TAC CAC TGG CCA GCG TCT TCC CTT C-3′ (−120/+66); and 5′-AAA TGG TAC CTG CCT CCT TCC TCA TGC CTG-3′ (−1/+66). The PCR products were cloned into the Asp718I and XhoI sites of the pGL3/basic vector. Mutation of putative Ets-2-binding sites (EBS) was carried out by two-step PCR mutagenesis using primers that amplified pStab1(−978/+66) as well as the following primers: mEBS1, 5′-AAA AGC TAG CTC CGC CTG CAG GCT GC-3′ and 5′-AAA AGC TAG CGA CGC TGG CCA GTG AC-3′; mEBS2, 5′-AAA AGC TAG CAA ATC CTG GTG GGT TC-3′ and 5′-AAA AGC TAG CGC GTA GCA GAC GCC TGC AG-3′; and mEBS3, 5′-AAA AGC TAG CTG GGG GTG AGC TGA CG-3′ and 5′-AAA AGC TAG CCC CAC CAG GAT TTC CTC C-3′. All of the plasmid constructs were verified by DNA sequencing (Bionics, Korea).

Reporter Gene Assays

Raw264.7 cells were seeded in 12-well plates at a density of 1.5 × 105 cells/well. The next day, the cells were transfected with pGL3/basic or pStab1-luc vector together with Ets-2 expression vector using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent, in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). Twenty-four hours after transfection, the cells were washed with PBS and lysed in 200 μl of reporter lysis buffer (Promega). Luciferase activities were measured using a dual luciferase assay kit, in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions (Promega). Transfection efficiency was determined in all of the samples by cotransfection with 0.1 μg of plasmid encoding the Renilla luciferase gene (pRL-SV40), and luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla luciferase activity. For experiments under different pH conditions, the medium was replaced with pH 7.4 or 6.4 medium after transfection. The next day, luciferase activities were measured as above.

Western Blotting

Raw264.7 cells were lysed in cold lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and proteinase inhibitors) for 30 min on ice. Identical amounts (20 μg of protein) of total cell lysates were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE and then transferred onto nitrocellular membranes. The membranes were incubated in blocking solution consisting of 5% skim milk in TBS-T (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by immunoblotting with anti-Ets-2 or anti-actin antibody (Sigma). Immunoreactive bands were visualized using an ECL kit (Amersham Biosciences). In some experiments, nuclear extracts were isolated from Raw264.7 cells and subjected to immunoblotting using anti-Ets-2 or anti-YY1 antibody.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay

ChIP assays were performed using an Upstate Biotechnology ChIP assay kit, in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, Raw264.7 cells were cross-linked by incubation with 1% formaldehyde at room temperature for 10 min. The cells were then washed with PBS and sonicated to yield DNA fragments ranging in size from 200 to 1000 bp. Sonicated samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 4 °C (12,000 rpm), after which supernatants were recovered, diluted 10-fold with ChIP dilution buffer, and then precleared by incubation with 75 μl of salmon sperm DNA with protein G-agarose and 50% slurry for 30 min at 4 °C with agitation to reduce the nonspecific interaction of chromatin DNA with the agarose beads. Supernatants were immunoprecipitated with anti-Ets1/2 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or isotype-matched antibody (anti-Ets-1; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Immunoprecipitated complexes were eluted from the protein G-agarose beads using elution buffer (1% SDS, 0.1 m NaHCO3). The DNA was separated from the immunoprecipitated samples and then used as templates for PCRs. The genomic primer sequences were as follows: pStab1 forward primer (5′-ACT GGC CAG CGT CTT CCC TTC-3′ (−119/−99)) and pStab1 reverse primer (5′-GAC AGT GAT TGC AGC AGC GG-3′ (+47/+66)). As negative controls, we used GAPDH primers as follows: GAPDH forward primer (5′-TGC CAC CCA GAA GAC TGT G-3′) and GAPDH reverse primer (5′-ATG TAG GCC ATG AGG TCC AC-3′).

Phagocytosis of PS-exposed RBC

PS-exposed RBC were prepared by incubation in PBS (20% hematocrit) at 37 °C for 4–5 days, as previously described (25). Exposure of PS on the surface of the RBC was detected using an annexin V apoptosis detection kit (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Peritoneal macrophages and Raw264.7 cells were seeded in 6-well plates. The next day culture medium was changed with pH 7.4 or 6.8 medium, and the cells were preincubated for 4 h at 37 °C. PS-exposed RBC or PS beads were then added to peritoneal macrophages or Raw264.7 cells, followed by incubation for 1 h at 37 °C to assess engulfment under different pH conditions. The different pH levels of the complete medium were achieved using different amounts of sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3) (3.7 or 1.0 g/liter in DMEM and 2.0 or 0.5 g/liter in RPMI 1640 for pH 7.4 and 6.8 media, respectively), as previously described (26). After washing away the unbound RBC, the nonengulfed RBC (surface binding) were lysed by treatment with deionized H2O for 10 s, followed by immediate replacement with DMEM as previously described (25). The cells were then stained using a Diff Quick staining kit (IMEB Inc.). The phagocytosis index was determined based on the number of engulfed cells per macrophage, as described previously (27). At least 200 cells were scored per well, and all of the experiments were repeated at least three times. For function-blocking experiments, the cells were preincubated with an anti-stabilin-1 antibody or isotype-matched control antibody for 1 h, followed by incubation with PS-exposed RBC.

Phagocytosis of PS-coated Beads

The fluorescence-labeled PS beads were generated as previously described (23). Briefly, Nucleosil 120–3 C18 beads (3 μm; Richard Scientific) were dissolved in chloroform, after which a mixture of PC:PS:NBD-PC (45:50:5 mol%) was added before drying under nitrogen. The beads were rehydrated with PBS and briefly sonicated before use. For the experiment, PS-coated beads were added to peritoneal macrophages. After 20 min of incubation at 37 °C, the noningested beads were removed by extensive washing. To further identify the engulfed cells, fluorescence derived from the bound beads (remnant beads) was quenched using 0.4% trypan blue as previously described (23). The uptake of PS-coated beads was quantified via fluorescent microscopy following trypan blue quenching. The phagocytosis index was determined by calculating the number of engulfed beads per macrophage.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance was assessed by analysis of variance or t test. A p value of < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Stabilin-1 Expression in Macrophages Is Increased by Low pH Medium

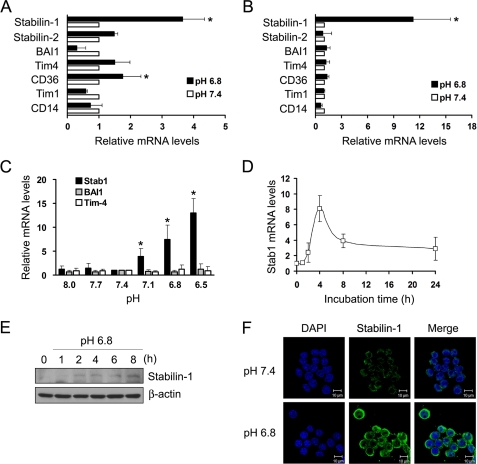

Extracellular low pH is associated with inflammation sites, in which macrophages play an important role in clearance of inflammatory cells. Considering that acidic pH can modulate function of immune cells via regulation of gene expression (28–30), extracellular low pH may regulate the expression of a receptor involved in PS-specific clearance of apoptotic cells. To investigate this, we examined the expression of PS-recognizing receptors in macrophages under neutral and low pH conditions using quantitative real time PCR. Incubation of peritoneal macrophages with low pH medium resulted in an ∼3.5-fold increase in stabilin-1 mRNA expression (Fig. 1A). CD36 expression was slightly increased in peritoneal macrophages in low pH medium. Similar to that observed with peritoneal macrophages, treatment with low pH medium also increased stabilin-1 expression in Raw264.7 cells, a macrophage cell line by 10-fold (Fig. 1B). When Raw264.7 cells were incubated with different pH medium, the level of stabilin-1 mRNA was increased with decreasing pH (Fig. 1C). In contrast, the levels of Tim-4 and BAI1 mRNA were not affected by the change of pH. Expression of stabilin-1 was increased in a time-dependent manner after incubation with low pH media, peaked at 4 h, and progressively declined thereafter (Fig. 1D). Immunoblot analysis showed that stabilin-1 protein was increased after incubation with low pH medium for 2 h (Fig. 1E). Immunofluorescent staining showed that expression of stabilin-1 protein was increased in response to low pH (Fig. 1F). These results show that extracellular low pH selectively induces the expression of stabilin-1 but not other PS receptors involved in cell corpse clearance.

FIGURE 1.

Expression of stabilin-1 is specifically increased by extracellular low pH. A and B, expression of PS recognition receptors in neutral or low pH medium was examined in peritoneal macrophages (A) and Raw264.7 cells (B) using quantitative real time PCR. The relative expression levels were plotted against that of each gene in neutral pH medium, which was set as 1. The results are expressed as the means ± S.D. from three independent experiments. t test: *, p < 0.01. C, expression of Stab1, Tim-4, and BAI1 in different pH medium. Raw264.7 cells were incubated in the indicated pH medium for 4 h, and expression of Stabilin-1, Tim-4, and BAI1 mRNA was examined by quantitative real time PCR. The results are expressed as the means ± S.D. from three independent experiments. D, Raw264.7 cells were incubated in low pH medium for the indicated times, and expression of stabilin-1 mRNA was examined by quantitative real time PCR. The results are expressed as the means ± S.D. from three independent experiments. E, Raw264.7 cells were incubated in low pH medium for the indicated times, and expression of stabilin-1 protein was examined by Western blotting. F, Raw264.7 cells were incubated in neutral or low pH medium for 4 h, and expression of stabilin-1 protein was examined by immunostaining using anti-stabilin-1 antibody (1bR1). Scale bar, 10 μm.

Stabilin-1 Expression Is Transcriptionally Regulated by Low pH-responsive Regions in Mouse Stabilin-1 Promoter

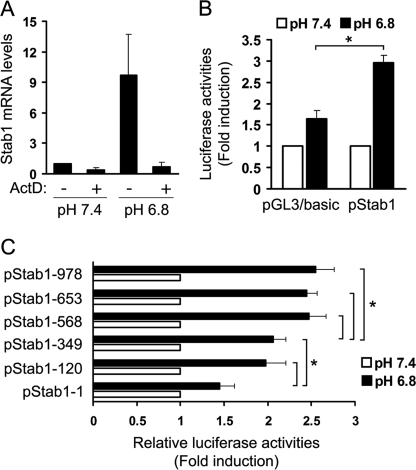

To clarify the mechanism through which low pH medium increases stabilin-1 expression, we investigated whether or not low pH modulates the stability of stabilin-1 mRNA. For this, we treated Raw264.7 cells with low pH medium in the absence or presence of actinomycin D, which is a transcriptional inhibitor that blocks further incorporation of uridine into RNA, and examined stabilin-1 expression. As shown in Fig. 2A, the up-regulation of stabilin-1 mRNA by low pH medium was abolished by treatment with actinomycin D, indicating that the increase in stabilin-1 mRNA expression by low pH medium was not due to an increase in mRNA stability. Next, to determine whether or not stabilin-1 mRNA up-regulation was the result of transcriptional activation, the mouse stabilin-1 promoter (pStab1-luc) consisting of ∼1000 bp (−978/+66) was generated (supplemental Fig. S1) and transfected into Raw264.7 cells, after which the luciferase activity at low pH was measured. Whereas control vector (pGL3/basic) showed a minimal change in luciferase activity at low pH, the activity of the mouse stabilin-1 promoter was increased by ∼3-fold in response to low pH (Fig. 2B). To identify important regions in the transcriptional activation of the mouse stabilin-1 promoter at low pH, we generated a series of 5′ deletion mutants of the mouse stabilin-1 promoter. These constructs were transfected into Raw264.7 cells, and their activities in low pH medium were examined. Deletion from −568 to −349 resulted in a slight reduction in low pH-induced promoter activity, whereas deletion from −120 to −1 caused a decrease in promoter activity to basal level (Fig. 2C). This suggests that the −568/−349 and −120/−1 regions were important for stabilin-1 promoter activity at low pH.

FIGURE 2.

Expression of stabilin-1 is increased by extracellular low pH. A, Raw264.7 cells were preincubated with or without actinomycin D (ActD), a transcriptional inhibitor, and then incubated with neutral or low pH medium for 4 h. Expression of stabilin-1 mRNA was examined by quantitative real time PCR. The results are expressed as the means ± S.D. from three independent experiments. B, analysis of mouse stabilin-1 promoter activity under neutral or low pH conditions. The activity of a luciferase reporter gene driven by the mouse stabilin-1 promoter was measured after transfection of Raw264.7 cells with pStab1 or pGL3/basic vector. Luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla luciferase activity and is shown as the fold increase in luciferase activity over that obtained under neutral pH. The results are expressed as the means ± S.D of three independent experiments. t test: *, p < 0.05. C, the full-length (−978/+66) mouse stabilin-1 promoter, as well as a series of 5′ deletion mutants, were transfected into Raw264.7 cells. At 12 h post-transfection, the cells were incubated with low pH medium for 16 h. The relative luciferase activities were plotted against that of each promoter in neutral pH medium, which was set as 1. The results are expressed as the means ± S.D. of at least three independent experiments. t test: *, p < 0.05.

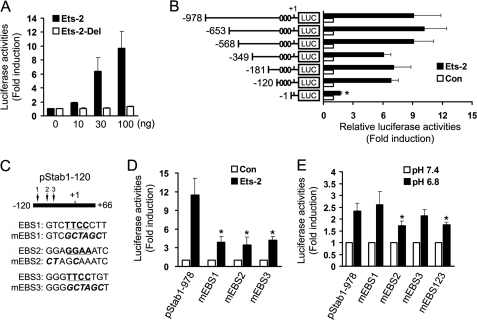

Ets-2 Regulates Transcriptional Activation of Stabilin-1 Gene in Macrophages

We investigated the transcription factors that may be required for inducible stabilin-1 expression in the −568/−349 and −120/−1 regions of the mouse stabilin-1 promoter using TESS and TFSEARCH (supplemental Fig. S2, A and B). When the effects of these transcription factors on the mouse stabilin-1 promoter were examined in Raw264.7 cells, we found that overexpression of Ets-2 resulted in 8-fold increase in stabilin-1 promoter activity (supplemental Fig. S2C). Ets-2 increased stabilin-1 promoter activity in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3A). An Ets-2 mutant form that lacks its Ets domain with DNA binding activity has no effect on the stabilin-1 promoter activity, even with high amounts of this mutant form (Fig. 3A). To investigate whether or not Ets-2-binding sites exist in the low pH-responsive regions, a series of 5′ deletion mutants of the stabilin-1 promoter were cotransfected with Ets-2 expression vector into Raw264.7 cells. Deletion from −120 to −1 abolished Ets-2-mediated activation of the stabilin-1 promoter (Fig. 3B), which is in agreement with the results of our promoter study at low pH. This result indicates that the Ets-2-responsive element in the low pH-responsive −120/−1 region is important in the regulation of stabilin-1 expression. Using computer-based sequence analysis, we found that there were three putative EBS in this region. These sites were found to be conserved in the rat, mouse, and human stabilin-1 promoters (supplemental Fig. S2D). To further identify which region is a cis-responsive element for Ets-2, we generated stabilin-1 promoters containing mutations of each Ets-2-responsive element (Fig. 3C). Each mutant promoter showed a significant decrease in transcriptional activation by Ets-2 (Fig. 3D). We next investigated the effects of EBS mutations on low pH-mediated activation of the stabilin-1 promoter. Mutation of the first and third Ets-2-responsive elements (mEBS1 and mEBS3) resulted in promoter activities comparable with that of the wild-type promoter in response to low pH, whereas mutation of the second Ets-2-responsive element (mEBS2) and of three Ets-2-responsive elements (mEBS123) significantly reduced the promoter activity in response to low pH compared with that of the wild-type promoter (Fig. 3E). This result indicates that the Ets-2-binding site in the −77/−66 region plays a pivotal role in low pH-induced stabilin-1 transcription. However, mutation of first EBS in the stabilin-1 promoter increased the basal activity of the stabilin-1 promoter (supplemental Fig. S3). Considering that Ets family proteins share similar binding site, it is possible that some Ets family protein acts as a transcription repressor in the stabilin-1 promoter (31, 32).

FIGURE 3.

Ets-2 is involved in transactivation of staiblin-1 at the −77/−66 region. A, the mouse stabilin-1 promoter construct was cotransfected with the indicated amount of wild-type or mutant Ets-2 expression vector into Raw264.7 cells. Relative luciferase activities were plotted against that of the mouse stabilin-1 promoter in the absence of Ets-2, which was set as 1. The results are expressed as the means ± S.D. of at least three independent experiments. B, identification of the Ets-2-responsive region of the mouse stabilin-1 promoter. The full-length mouse stabilin-1 promoter (−978/+66) and a series of 5′ deletion mutants were cotransfected with Ets-2 expression vector or empty vector into Raw264.7 cells. The relative luciferase activities were plotted against that of each promoter in the absence of Ets-2, which was set as 1. The results are expressed as the means ± S.D. of at least three independent experiments. Putative Ets-2-binding sites are indicated as ovals. t test: *, p < 0.01. C, schematic representation of putative EBS and their mutants in the mouse stabilin-1 promoter. D, the full-length mouse stabilin-1 promoter (−978/+66) and EBS mutants were cotransfected with Ets-2 expression vector into Raw264.7 cells. The relative luciferase activities were plotted against that of each promoter in the absence of Ets-2, which was set as 1. The results are expressed as the means ± S.D. of at least three independent experiments. t test: *, p < 0.01 versus wild-type promoter. E, the full-length mouse stabilin-1 promoter (−978/+66) and EBS mutants were transfected into Raw264.7 cells. At 12 h post-transfection, the cells were incubated with low pH medium for 16 h. The relative luciferase activities were plotted against that of each promoter in neutral pH medium, which was set as 1. The results are expressed as the means ± S.D. of at least three independent experiments. t test: *, p < 0.01 versus wild-type promoter. Con, control.

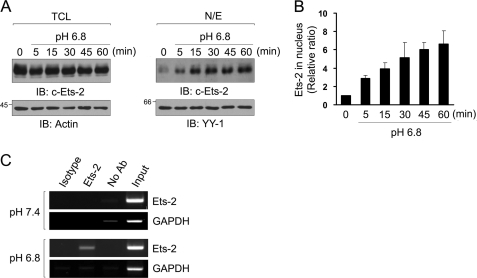

Low pH Induces Nuclear Translocation of Ets-2, Thereby Binding to Ets-2-responsive Element

To investigate the effect of low pH on expression and nuclear translocation of Ets-2 protein, the amount of Ets-2 in total cell lysates and nuclear extract of Raw264.7 cells was measured at the indicated times. The total amount of Ets-2 protein was slightly decreased by treatment with low pH medium (Fig. 4A, left panels). On the other hand, the amount of Ets-2 in the nucleus was increased with time under low pH conditions (Fig. 4, A, right panels, and B), suggesting the role of Ets-2 in transcriptional regulation under low pH conditions. Next, to identify direct binding of Ets-2 to the low pH-responsive element of the stabilin-1 promoter in the nucleus, we performed ChIP assays in Raw264.7 cells incubated at neutral or low pH medium for 1 h. When the cells were incubated with neutral pH medium, the region containing the Ets-2-responsive element was not amplified from genomic DNA that was precipitated using an anti-Ets1/2 antibody (Fig. 4C, upper panels). However, when the cells were incubated with low pH medium for 1 h, the 185-bp fragment encompassing the Ets-2-responsive regions was amplified using the specific primers (Fig. 4C, lower panels). When an anti-Ets-1 antibody was used as a control, no signal was observed in the PCR amplification under either condition (Fig. 4C). Taken together, these results demonstrate that Ets-2 proteins translocate into the nucleus in a low pH environment and directly bind to the low pH-responsive region in the mouse stabilin-1 promoter. These results further indicate that translocation of Ets-2 at low pH plays a critical role in low pH-mediated stabilin-1 expression.

FIGURE 4.

Extracellular low pH induces translocation of Ets-2, thereby binding to the Ets-2-responsive element. A, Raw264.7 cells were incubated in low pH medium for the indicated time, and the amounts of Ets-2 protein in total cell lysates (TCL, left panels) and nuclear extracts (N/E, right panels) were analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-Ets-2 antibody. B, immunoblot intensities for Ets-2 in the nuclear extracts were quantitated by densitometry and normalized by YY-1 intensity. The relative intensities are expressed in arbitrary units. The intensity of the zero time point was set to one. The results are expressed as the means ± S.D. of three independent experiments. C, chromatin immunoprecipitation assays. Raw264.7 cells were incubated in neutral or low pH medium for 1 h. Soluble chromatin was prepared from the cells and immunoprecipitated with anti-Ets-1/2 antibody (lane 2) or an isotype-matched control antibody (anti-Ets-1) (lane 1). Immunoprecipitates were subjected to PCR with primers corresponding to the EBS in the mouse stabilin-1 promoter. As a negative control, GAPDH primers were used. IB, immunoblot.

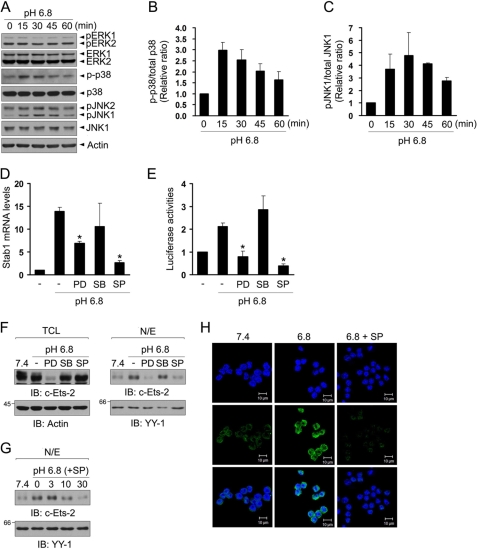

JNK Is Involved in Low pH-mediated Stabilin-1 Expression

To elucidate signal transduction in response to extracellular acidification, we analyzed the phosphorylation of Erk1/2, p38 MAPK, and JNK in Raw264.7 cells after treatment with low pH medium. After stimulation with low pH medium, the phosphorylation of JNK and p38 MAPK was increased with time, whereas phosphorylation of Erk1/2 did not change (Fig. 5A). The phosphorylation of p38 and pJNK peaked at 15 and 30 min, respectively (Fig. 5, B and C). To examine the involvement of MAPKs in stabilin-1 expression, Raw264.7 cells were incubated with low pH medium in the presence of PD98059 (a specific Erk1/2 inhibitor), SB203580 (a specific p38 MAPK inhibitor), or SP600125 (a specific JNK inhibitor), after which stabilin-1 expression was measured. Inhibition of the JNK pathway mostly abrogated the increase in stabilin-1 expression by low pH (Fig. 5D). Treatment with PD98059, an inhibitor of Erk1/2, also inhibited low pH-mediated stabilin-1 expression by ∼50%. The activity of the stabilin-1 promoter was inhibited by both the Erk1/2 and JNK inhibitors (Fig. 5E). It is well known that expression of Ets-2 is regulated by the Erk1/2 pathway, and translocation of Ets-2 is also modulated by MAPKs (33). Thus, we examined the effects of MAPK inhibitors on the expression and low pH-mediated translocation of Ets-2. Treatment with JNK inhibitor inhibited low pH-mediated translocation of Ets-2 to the same degree as that in neutral pH (Fig. 5F, right panels), and this inhibitory effect was dose-dependent (Fig. 5G). Consistent with the role of JNK pathway in nuclear translocation of Ets-2, JNK inhibitor abrogated the increase in stabilin-1 protein by low pH (Fig. 5H). These results indicate that the JNK pathway might play an important role in the translocation of Ets-2, thereby inducing stabilin-1 expression. PD98059, an inhibitor of Erk1/2, significantly reduced Ets-2 expression (Fig. 5F, left panels), indicating that PD98059 inhibited low pH-mediated stabilin-1 expression via the decrease of Ets-2 protein. This finding supports a role for Ets-2 in stabilin-1 expression.

FIGURE 5.

JNK is important for Ets-2-mediated stabilin-1 expression at low extracellular pH. A, Raw264.7 cells were stimulated with low pH medium for the indicated time. Total cell lysates were immunoblotted for phosphor-Erk, phosphor-p38 MAPK, and phosphor-JNK. A representative result of three independent experiments is shown. B and C, immunoblot intensities for p-p38/p38 (B) and pJNK/JNK (C) were quantitated by densitometry and expressed in arbitrary units. The intensity of the zero time point was set to one. The results are expressed as the means ± S.D. of three independent experiments. D, Raw264.7 cells were incubated with neutral or low pH medium for 4 h in the presence of the indicated MAPK inhibitors. Expression of stabilin-1 mRNA was analyzed by real time quantitative PCR. t test: *, p < 0.01. E, Raw264.7 cells were transfected with the stabilin-1 promoter construct and then incubated with low pH medium in the presence of the indicated MAPK inhibitors. The relative luciferase activities were plotted against that of the promoter in pH 7.4 medium, which was set as 1. The results are expressed as the mean ± S.D. of at least three independent experiments. t test: *, p < 0.01. F, Raw264.7 cells were incubated with neutral or low pH medium for 1 h in the presence of Erk1/2 (PD98059, PD), p38 (SB203580, SB), or JNK inhibitor (SP600125, SP), and the amounts of Ets-2 protein in total cell lysates (TCL, left panels) and nuclear extracts (N/E, right panels) were analyzed by immunoblotting (IB) using anti-Ets-2 antibody. G, Raw264.7 cells were incubated with neutral or low pH medium for 1 h in the presence of three different concentrations (3, 10, or 30 μm) of JNK inhibitor (SP600125), and the amount of Ets-2 protein in the nuclear extracts was analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Ets-2 antibody. H, Raw264.7 cells were incubated in neutral or low pH medium for 4 h in the presence or absence of JNK inhibitor, and expression of stabilin-1 protein was examined by immunostaining using anti-stabilin-1 antibody (1bR1). Scale bar, 10 μm.

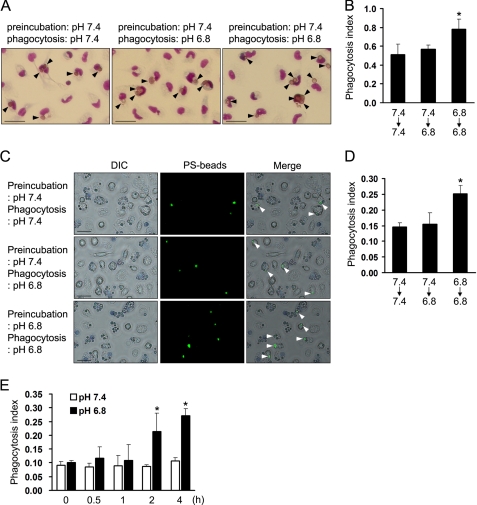

Extracellular Low pH Enhances Phagocytic Capacity of Peritoneal Macrophages

To determine whether or not extracellular low pH affects the phagocytic activity of macrophages, we examined the phagocytic activity of macrophages at neutral pH (pH 7.4) and low pH (pH 6.8) medium using PS-exposed RBC. When peritoneal macrophages were preincubated in neutral pH medium, phagocytic activity has no difference in both conditions. However, preincubation of macrophages with low pH medium for 4 h caused a 1.5-fold increase in engulfment of PS-exposed RBC in low pH medium (Fig. 6, A and B). Because a change in the environmental pH can induce a change in the phospholipid distribution of the RBC membrane (34), we performed phagocytosis assays using apoptotic-mimicked PS beads. Consistent with the result with PS-exposed RBC, pretreatment with low pH medium caused a 1.7-fold increase in engulfment of PS beads (Fig. 6, C and D). We also performed phagocytosis assays after preincubation with low pH medium for different times. In agreement with the increase of stabilin-1 expression, phagocytic activity of macrophages was increased by incubating with low pH medium for 2 h (Fig. 6E). These results indicate that preincubation at low pH enhances PS-dependent phagocytosis in macrophages.

FIGURE 6.

Extracellular low pH increases phagocytic activity of macrophages. A, representative images of PS-exposed RBC engulfment by peritoneal macrophages under the indicated conditions. The cells were preincubated with neutral or low pH medium for 4 h and then incubated with PS-exposed RBC for 1 h in neutral or low pH medium. Three independent experiments were performed, and a representative result is shown. The arrowheads indicate the engulfed PS-exposed RBC. Scale bar, 25 μm. B, phagocytosis assays were conducted under the indicated conditions using PS-exposed RBC as target cells, and the phagocytosis index (the number of engulfed cells per macrophage) was determined. The results are expressed as the means ± S.D. from three independent experiments. Analysis of variance: *, p < 0.05. C, representative images of PS bead engulfment by peritoneal macrophages under neutral or low pH conditions. The cells were preincubated with neutral or low pH medium for 4 h and then incubated with PS-coated beads for 1 h in neutral or low pH medium. PS beads engulfed in macrophages are shown in green (arrowheads). Three independent experiments were performed, and representative results are shown. Scale bar, 25 μm. DIC, differential interference contrast. D, phagocytosis assays were conducted under the indicated conditions, and the phagocytosis index (the number of engulfed beads per macrophage) was determined. The results are expressed as the means ± S.D. from three independent experiments. Analysis of variance: *, p < 0.05. E, Raw264.7 cells were preincubated with low pH medium for the indicated times and then incubated with PS-coated beads for 1 h in neutral or low pH medium. The phagocytosis index was determined and expressed as the means ± S.D. from three independent experiments. t test: *, p < 0.05 versus pH 7.4.

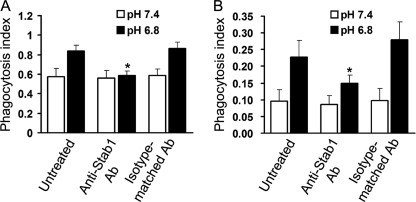

Enhanced Phagocytosis by Low pH Is Dependent on Stabilin-1

To investigate the involvement of stabilin-1 in the enhancement of the phagocytic capacity of macrophages under low pH conditions, we attempted to determine whether or not blockade of stabilin-1 attenuates the low pH-mediated enhancement of phagocytosis using an antibody (N-13) previously characterized for its ability to block stabilin-1 function (23, 24). Under neutral pH conditions, in which stabilin-1 is rarely expressed in peritoneal macrophages, treatment with anti-stabilin-1 antibody had no effect on phagocytosis. Under low pH conditions, treatment with an anti-stabilin-1 antibody reduced the phagocytosis of PS-exposed RBC (from 0.84 ± 0.058 to 0.59 ± 0.047) to the same degree as that observed at neutral pH, whereas an isotype-matched antibody had no effect (from 0.84 ± 0.058 to 0.87 ± 0.063) (Fig. 7A). Enhancement of phagocytosis by low pH was more prominent in Raw264.7 cells (from 0.096 ± 0.034 to 0.23 ± 0.05) (Fig. 7B), which is in agreement with the result of stabilin-1 expression in low pH. Treatment of anti-stabilin-1 antibody significantly reduced the phagocytosis of PS-coated beads (from 0.23 ± 0.05 to 0.15 ± 0.024) (Fig. 7B). This result indicates that stabilin-1 plays an important role in low pH-mediated enhancement of phagocytic capacity in macrophages.

FIGURE 7.

Stabilin-1-mediated phagocytosis is enhanced by extracellular low pH. A, peritoneal macrophages were treated with anti-stabilin-1 antibody (10 μg/ml) or an isotype-matched control antibody (10 μg/ml) prior to the addition of PS-exposed RBC. Phagocytosis assays were conducted under neutral or low pH conditions, and the phagocytosis index (the number of engulfed cells per macrophage) was determined. The results are expressed as the means ± S.D. from three independent experiments. t test: *, p < 0.05. B, Raw264.7 cells were treated with anti-stabilin-1 antibody (10 μg/ml) or an isotype-matched control antibody (10 μg/ml) prior to the addition of PS-coated beads. Phagocytosis assays were conducted under neutral or low pH conditions, and the phagocytosis index (the number of engulfed cells per macrophage) was determined. The results are expressed as the means ± S.D. from three independent experiments. t test: *, p < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

A low pH microenvironment is a characteristic feature of inflammation loci, where the apoptotic loss of inflammatory neutrophils and their subsequent clearance by macrophages are necessary for resolution of inflammation. Several studies have previously reported that acidic pH can modulate function of immune cells via regulation of gene expression (28–30). Based on these findings, we hypothesized that acidic environments can modulate functions of macrophages, thereby affecting the phagocytic capacity of macrophages. Here, we provide four lines of evidence supporting that a low extracellular pH is responsible for up-regulation of phagocytic receptor stabilin-1. First, treatment with low pH medium up-regulated stabilin-1 expression in macrophages at both the mRNA and protein levels. Second, Ets-2 increased promoter activity of stabilin-1 gene in macrophages. Third, Ets-2 translocated into the nucleus in response to low pH and directly bound to the Ets-2-reponsive element in the mouse stabilin-1 promoter. Fourth, extracellular low pH induced phosphorylation of JNK, and a JNK-specific inhibitor abrogated Ets-2 translocation and low pH-mediated stabilin-1 expression. Thus, these results demonstrate that an acidic environment up-regulates stabilin-1 expression via Ets-2.

Ets-2 is a member of the Ets transcriptional factor family and is involved in the regulation of many biological processes, including cell proliferation, differentiation, immune responses, and apoptosis (35). The DNA domain of Ets-2 protein interacts with GGA(A/T)-containing DNA elements. Targeted deletion of the conserved DNA-binding domain of Ets-2 transcription factor results in the death of homozygous embryos before embryonic day 8.5 (E8.5) (36), suggesting that Ets-2 is an important factor in early development. Specific signaling pathways directly affect the activity of several Ets proteins by regulating their nuclear translocation, DNA binding activity, or stability (35). In this study, we demonstrated that low pH rapidly stimulated the nuclear translocation of Ets-2 in a JNK-dependent manner. In agreement with this finding, we found that Ets-2 directly bound to the Ets-2-responsive region in the mouse stabilin-1 promoter in response to low pH and acted as a transcriptional mediator of low pH-induced stabilin-1 expression in macrophages. However, it is possible that Ets-2 is not the only transcription factor driving low pH-induced stabilin-1 expression, because the −568/−349 region is also a low pH-responsive region in the mouse stabilin-1 promoter. Moreover, inhibition of Ets-2 expression by Erk1/2 inhibitor resulted in only partial reduction of the expression and promoter activity of stabilin-1. Although the amount of Ets2 in nucleus is reduced to a similar degree by both the Erk1/2 and JNK inhibitors, only inhibition of JNK pathway attenuated stabilin-1 expression to the same degree as that at neutral pH. Thus, another transcription factor regulated by the JNK pathway may also be involved in low pH-induced stabilin-1 expression via the −568/349 region in the mouse stabilin-1 promoter.

Although it has been reported that the extracellular pH affects the function of immune cells, including polymorphonuclear leukocytes, neutrophils, and macrophages (37), the effect of low extracellular pH on the phagocytosis of apoptotic cells has not been fully investigated. Previously, phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils by human macrophages was reduced in pH 6.5 medium compared with pH 7.5 (38). This finding suggests a “charge-sensitive” mechanism of uptake, presumably through changes in the ability of receptors to recognize charged moieties on the surface of apoptotic cells. However, our result showed that there is no difference in phagocytic activity of mouse peritoneal macrophages in pH 6.8 and 7.4 medium after preincubation with pH 7.4 medium. This discrepancy may be explained by different population of macrophages and target cells or by pH difference between pH 6.5 and 6.8. In this study, we found that treatment with low pH medium for 4 h up-regulated the expression of stabilin-1, which is involved in PS-dependent clearance of apoptotic cells and PS-exposed RBC. In agreement with this finding, preincubation with low pH medium is required to enhance phagocytic activity in acidic environments. Function blocking experiment showed that anti-stabilin-1 antibody inhibited enhancement of phagocytosis by low pH.

Although the results of the present study show that low extracellular pH accelerated the phagocytic clearance of apoptotic cells via up-regulation of the phagocytic receptor stabilin-1, increased clearance by low pH may be explainable by other mechanisms. One possibility is that pH-dependent modifications of the target cell surface affect clearance by macrophages. We excluded this possibility using PS-coated beads as a target. Alternatively, it is possible that extracellular acidification affects the interaction between phagocytic receptors and PS. A previous study reported that the interaction between annexin V and phosphatidylserine-containing vesicles can be increased by low pH (39). Recently, we demonstrated that the conserved histidines of the EGF-like domain repeats in stabilin-2, which is a homolog of stabilin-1 with a similar domain structure, modulate the pH-dependent recognition of phosphatidylserine in apoptotic cells (26, 40). Similarly, the EGF-like domain repeats of stabilin-1 are required for its PS recognition (23). Histidine residues are also conserved in four EGF-like domain repeats in stabilin-1. Indeed, we found that L cells stably transfected with stabilin-1 showed enhanced phagocytosis in low pH medium.3 Therefore, the PS binding capacity of stabilin-1 could be increased under a low pH microenvironment, thus contributing to an increase in the phagocytic capacity of stabilin-1-up-regulated macrophages.

The key event in tissue resolution from inflammation is the apoptosis of inflammatory polymorphonuclear neutrophils followed by their clearance by macrophages. PS-dependent phagocytosis by macrophages also contributes to the regulation of inflammation via the release of anti-inflammatory cytokines and suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (9). Several studies suggest that acidic environments affect the resolution of inflammation. Acidification of the peritoneal cavity decreases serum TNF-α levels in response to LPS and is correlated with the degree of reduction of the inflammatory response (12). Sensing of extracellular acidification by the proton-sensing receptor TDAG8 results in inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokine production in peritoneal macrophages (13). Recent studies have shown that Tim-4, BAI1, and stabilin-2 are candidates of the PS receptor and are involved in cell corpse clearance (41). We recently demonstrated that stabilin-1 also mediates PS-dependent engulfment of cell corpses in alternatively activated macrophages (23). Thus, it is possible that the increase in stabilin-1-mediated phagocytosis by low pH accelerates the release of anti-inflammatory cytokines and suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, thereby contributing to inflammation resolution.

In summary, we demonstrated that extracellular low pH regulated stabilin-1 expression via the Ets-2 and JNK signal pathway, thereby modulating the phagocytic capacity of macrophages. This study should help elucidate the molecular mechanism by which apoptotic cell clearance occurs during resolution of inflammation, as well as the mechanism by which stabilin-1 is regulated under many physiological and pathological conditions. Although a low pH microenvironment is a characteristic feature of inflammatory loci, local acidosis is also found in several biological processes such as neoplastic growth and bone absorption. Considering the multiple functions of stabilin-1, up-regulation of stabilin-1 expression by low pH may play a role in several biological processes associated with acidic environments.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology Grants 2009-0068687 and 2011-0016102; by the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by Korea government Grant 2010-0029206; by the Converging Research Center Program through Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology Grant 2010K001054; by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology Grant R11-2008-044-03001-0; and by the Brain Korea 21 Project.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3.

S.-Y. Park, D.-J. Bae, and I.-S. Kim, unpublished observations.

- PS

- phosphatidylserine

- RBC

- red blood cell(s)

- Ets-2

- v-Ets erythroblastosis virus E26 oncogene homolog 2

- EBS

- Ets-2-binding site.

REFERENCES

- 1. Dubos R. J. (1955) The micro-environment of inflammation or Metchnikoff revisited. Lancet 269, 1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kopaniak M. M., Issekutz A. C., Movat H. Z. (1980) Kinetics of acute inflammation induced by E. coli in rabbits. Quantitation of blood flow, enhanced vascular permeability, hemorrhage, and leukocyte accumulation. Am. J. Pathol. 98, 485–498 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Grimshaw M. J., Balkwill F. R. (2001) Inhibition of monocyte and macrophage chemotaxis by hypoxia and inflammation. A potential mechanism. Eur. J. Immunol. 31, 480–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. van Zwieten R., Wever R., Hamers M. N., Weening R. S., Roos D. (1981) Extracellular proton release by stimulated neutrophils. J. Clin. Invest. 68, 310–313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Edlow D. W., Sheldon W. H. (1971) The pH of inflammatory exudates. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 137, 1328–1332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ward T. T., Steigbigel R. T. (1978) Acidosis of synovial fluid correlates with synovial fluid leukocytosis. Am. J. Med. 64, 933–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tannock I. F., Rotin D. (1989) Acid pH in tumors and its potential for therapeutic exploitation. Cancer Res. 49, 4373–4384 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vaupel P., Kallinowski F., Okunieff P. (1989) Blood flow, oxygen and nutrient supply, and metabolic microenvironment of human tumors. A review. Cancer Res. 49, 6449–6465 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Savill J., Fadok V. (2000) Corpse clearance defines the meaning of cell death. Nature 407, 784–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ravichandran K. S., Lorenz U. (2007) Engulfment of apoptotic cells. Signals for a good meal. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 964–974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Erwig L. P., Henson P. M. (2008) Clearance of apoptotic cells by phagocytes. Cell Death Differ. 15, 243–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hanly E. J., Aurora A. A., Shih S. P., Fuentes J. M., Marohn M. R., De Maio A., Talamini M. A. (2007) Peritoneal acidosis mediates immunoprotection in laparoscopic surgery. Surgery 142, 357–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mogi C., Tobo M., Tomura H., Murata N., He X. D., Sato K., Kimura T., Ishizuka T., Sasaki T., Sato T., Kihara Y., Ishii S., Harada A., Okajima F. (2009) Involvement of proton-sensing TDAG8 in extracellular acidification-induced inhibition of proinflammatory cytokine production in peritoneal macrophages. J. Immunol. 182, 3243–3251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kzhyshkowska J., Gratchev A., Goerdt S. (2006) Stabilin-1, a homeostatic scavenger receptor with multiple functions. J. Cell Mol. Med. 10, 635–649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goerdt S., Bhardwaj R., Sorg C. (1993) Inducible expression of MS-1 high-molecular-weight protein by endothelial cells of continuous origin and by dendritic cells/macrophages in vivo and in vitro. Am. J. Pathol. 142, 1409–1422 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Politz O., Gratchev A., McCourt P. A., Schledzewski K., Guillot P., Johansson S., Svineng G., Franke P., Kannicht C., Kzhyshkowska J., Longati P., Velten F. W., Goerdt S. (2002) Stabilin-1 and -2 constitute a novel family of fasciclin-like hyaluronan receptor homologues. Biochem. J. 362, 155–164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Adachi H., Tsujimoto M. (2002) FEEL-1, a novel scavenger receptor with in vitro bacteria-binding and angiogenesis-modulating activities. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 34264–34270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tamura Y., Adachi H., Osuga J., Ohashi K., Yahagi N., Sekiya M., Okazaki H., Tomita S., Iizuka Y., Shimano H., Nagai R., Kimura S., Tsujimoto M., Ishibashi S. (2003) FEEL-1 and FEEL-2 are endocytic receptors for advanced glycation end products. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 12613–12617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kzhyshkowska J., Gratchev A., Brundiers H., Mamidi S., Krusell L., Goerdt S. (2005) Phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase activity is required for stabilin-1-mediated endosomal transport of acLDL. Immunobiology 210, 161–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kzhyshkowska J., Workman G., Cardó-Vila M., Arap W., Pasqualini R., Gratchev A., Krusell L., Goerdt S., Sage E. H. (2006) Novel function of alternatively activated macrophages. Stabilin-1-mediated clearance of SPARC. J. Immunol. 176, 5825–5832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kzhyshkowska J., Mamidi S., Gratchev A., Kremmer E., Schmuttermaier C., Krusell L., Haus G., Utikal J., Schledzewski K., Scholtze J., Goerdt S. (2006) Novel stabilin-1 interacting chitinase-like protein (SI-CLP) is up-regulated in alternatively activated macrophages and secreted via lysosomal pathway. Blood 107, 3221–3228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kzhyshkowska J., Gratchev A., Schmuttermaier C., Brundiers H., Krusell L., Mamidi S., Zhang J., Workman G., Sage E. H., Anderle C., Sedlmayr P., Goerdt S. (2008) Alternatively activated macrophages regulate extracellular levels of the hormone placental lactogen via receptor-mediated uptake and transcytosis. J. Immunol. 180, 3028–3037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Park S. Y., Jung M. Y., Lee S. J., Kang K. B., Gratchev A., Riabov V., Kzhyshkowska J., Kim I. S. (2009) Stabilin-1 mediates phosphatidylserine-dependent clearance of cell corpses in alternatively activated macrophages. J. Cell Sci. 122, 3365–3373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lee S. J., Park S. Y., Jung M. Y., Bae S. M., Kim I. S. (2011) Mechanism for phosphatidylserine-dependent erythrophagocytosis in mouse liver. Blood 117, 5215–5223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Park S. Y., Jung M. Y., Kim H. J., Lee S. J., Kim S. Y., Lee B. H., Kwon T. H., Park R. W., Kim I. S. (2008) Rapid cell corpse clearance by stabilin-2, a membrane phosphatidylserine receptor. Cell Death Differ. 15, 192–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kim S., Bae D. J., Hong M., Park S. Y., Kim I. S. (2010) The conserved histidine in epidermal growth factor-like domains of stabilin-2 modulates pH-dependent recognition of phosphatidylserine in apoptotic cells. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 42, 1154–1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yoshida H., Kawane K., Koike M., Mori Y., Uchiyama Y., Nagata S. (2005) Phosphatidylserine-dependent engulfment by macrophages of nuclei from erythroid precursor cells. Nature 437, 754–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bellocq A., Suberville S., Philippe C., Bertrand F., Perez J., Fouqueray B., Cherqui G., Baud L. (1998) Low environmental pH is responsible for the induction of nitric-oxide synthase in macrophages. Evidence for involvement of nuclear factor-κB activation. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 5086–5092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Martínez D., Vermeulen M., von Euw E., Sabatté J., Maggíni J., Ceballos A., Trevani A., Nahmod K., Salamone G., Barrio M., Giordano M., Amigorena S., Geffner J. (2007) Extracellular acidosis triggers the maturation of human dendritic cells and the production of IL-12. J. Immunol. 179, 1950–1959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Serrano C. V., Jr., Fraticelli A., Paniccia R., Teti A., Noble B., Corda S., Faraggiana T., Ziegelstein R. C., Zweier J. L., Capogrossi M. C. (1996) pH dependence of neutrophil-endothelial cell adhesion and adhesion molecule expression. Am. J. Physiol. 271, C962–C970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chung S. W., Chen Y. H., Yet S. F., Layne M. D., Perrella M. A. (2006) Endotoxin-induced down-regulation of Elk-3 facilitates heme oxygenase-1 induction in macrophages. J. Immunol. 176, 2414–2420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chung S. W., Chen Y. H., Perrella M. A. (2005) Role of Ets-2 in the regulation of heme oxygenase-1 by endotoxin. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 4578–4584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Han M., Yan W., Guo W., Xi D., Zhou Y., Li W., Gao S., Liu M., Levy G., Luo X., Ning Q. (2008) Hepatitis B virus-induced hFGL2 transcription is dependent on c-Ets-2 and MAPK signal pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 32715–32729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Libera J., Pomorski T., Müller P., Herrmann A. (1997) Influence of pH on phospholipid redistribution in human erythrocyte membrane. Blood 90, 1684–1693 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yordy J. S., Muise-Helmericks R. C. (2000) Signal transduction and the Ets family of transcription factors. Oncogene 19, 6503–6513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yamamoto H., Flannery M. L., Kupriyanov S., Pearce J., McKercher S. R., Henkel G. W., Maki R. A., Werb Z., Oshima R. G. (1998) Defective trophoblast function in mice with a targeted mutation of Ets2. Genes Dev. 12, 1315–1326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lardner A. (2001) The effects of extracellular pH on immune function. J. Leukocyte Biol. 69, 522–530 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Savill J. S., Henson P. M., Haslett C. (1989) Phagocytosis of aged human neutrophils by macrophages is mediated by a novel “charge-sensitive” recognition mechanism. J. Clin. Invest. 84, 1518–1527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Köhler G., Hering U., Zschörnig O., Arnold K. (1997) Annexin V interaction with phosphatidylserine-containing vesicles at low and neutral pH. Biochemistry 36, 8189–8194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Park S. Y., Kim S. Y., Jung M. Y., Bae D. J., Kim I. S. (2008) Epidermal growth factor-like domain repeat of stabilin-2 recognizes phosphatidylserine during cell corpse clearance. Mol. Cell Biol. 28, 5288–5298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bratton D. L., Henson P. M. (2008) Apoptotic cell recognition. Will the real phosphatidylserine receptor(s) please stand up? Curr. Biol. 18, R76–R79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.