Background: Mycolyl-arabinogalactan-peptidoglycan (mAGP) represents the hallmark of the mycobacterial cell envelope and the target of several antitubercular drugs.

Results: Loss of a glycolipid structurally analogous to the terminal portion of mAGP correlates with drug treatment in mycobacteria.

Conclusion: This work establishes the versatility of arabinoglycerolipids in M. tuberculosis.

Significance: Further work will define the importance of the metabolic relationship between the two components in cell wall remodeling and/or pathogenesis.

Keywords: Carbohydrate Metabolism, Cell Wall, Glycerolipid, Mycobacterium, NMR, Inhibition, Thiacetazone

Abstract

The “cell wall core” consisting of a mycolyl-arabinogalactan-peptidoglycan (mAGP) complex represents the hallmark of the mycobacterial cell envelope. It has been the focus of intense research at both structural and biosynthetic levels during the past few decades. Because it is essential, mAGP is also regarded as a target for several antitubercular drugs. Herein, we demonstrate that exposure of Mycobacterium bovis Bacille Calmette-Guérin or Mycobacterium marinum to thiacetazone, a second line antitubercular drug, is associated with a severe decrease in the level of a major apolar glycolipid. This inhibition requires MmaA4, a methyltransferase reported to participate in the activation process of thiacetazone. Following purification, this glycolipid was subjected to detailed structural analyses, combining gas-liquid chromatography, mass spectrometry, and nuclear magnetic resonance. This allowed to identify it as a 5-O-mycolyl-β-Araf-(1→2)-5-O-mycolyl-α-Araf-(1→1)-Gro, designated dimycolyl diarabinoglycerol (DMAG). The presence of DMAG was subsequently confirmed in other slow growing pathogenic species, including Mycobacterium tuberculosis. DMAG production was stimulated in the presence of exogenous glycerol. Interestingly, DMAG appears structurally identical to the terminal portion of the mycolylated arabinosyl motif of mAGP, and the metabolic relationship between these two components was provided using antitubercular drugs such as ethambutol or isoniazid known to inhibit the biosynthesis of arabinogalactan or mycolic acid, respectively. Finally, DMAG was identified in the cell wall of M. tuberculosis. This opens the possibility of a potent biological function for DMAG that may be important to mycobacterial pathogenesis.

Introduction

Human tuberculosis (TB),2 caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, remains one of the leading causes of death by infectious agents. The success of the bacterium is mainly due to its unique cell envelope that is directly implicated in the pathogenesis and resistance to antimicrobial drugs (1, 2). The mycobacterial cell wall relies on long-chain fatty acids, called mycolic acids, that are covalently linked to arabinogalactan, a polysaccharide that is cross-linked to the peptidoglycan backbone. The structure of the mycolyl-arabinogalactan-peptidoglycan (mAGP) varies from one species to the other and sometimes between mycobacterial strains. Differences result from the wide variety of mycolates according to their constituent chemical groups (double bond, cyclopropane, ketone, methoxyl, epoxyl, or carboxylic acid) (3). For instance, the M. tuberculosis cell envelope contains α-, keto-, and methoxymycolic acids, whereas the vaccine strain Mycobacterium bovis BCG Pasteur only synthesizes α- and ketomycolates. Regardless of their structures, mycolic acids attached to deacylated mAGP (AGP) form a cell surface lipid layer into which numerous free lipids/glycolipids are inserted, generating an effective external membrane-like permeability barrier (4, 5). These free lipids/glycolipids form precursors in the biosynthesis of mAGP (6), regulate cell division (7), and modulate virulence and host immunity (7–9). Because mAGP is essential for cell wall integrity and mycobacterial survival, its corresponding biosynthetic enzymes represent valid targets for several first line and second line antitubercular drugs, including isoniazid (INH), ethionamide, and ethambutol (EMB). INH and ethionamide inhibit enzymes required for mycolic acid synthesis (10), whereas EMB inhibits arabinosyltransferases involved in assembly of the arabinan domain of mAGP (11). Although these compounds are effective against drug-sensitive strains of M. tuberculosis, the emergence of multidrug-resistant and particularly extremely drug-resistant clinical isolates seriously hampers the use of these drugs. Thus, a need for continued progress in understanding the mechanism of current anti-TB agents, development of new lead compounds, and identification of novel pharmacological targets is clearly evident.

From a more fundamental perspective, mechanistic study of cell wall-inhibitory agents can lead to important insights into the essentiality of cell wall-associated components as well as into their biological functions. In this context, we have recently started to explore the mechanism(s) of activation and action of thiacetazone (TAC), a thiosemicarbazone antimicrobial that has been widely used for TB treatment in Africa and South America as a cheap and effective substitute for p-aminosalicylic acid (12). Because TAC is associated with dermatologic side effects and Stevens-Johnson syndrome in AIDS patients, it is not available anymore in the United States (13). Nevertheless, TAC may still be considered for the management of multidrug-resistant or extremely drug-resistant TB and for the treatment of new TB cases when there is a shortage of drugs (14, 15). Recently, TAC has been chosen as a pharmacophore for the development of chemical analogues, which have been evaluated for their potential in inhibiting the growth of the opportunistic species Mycobacterium avium and of M. tuberculosis H37Rv (16–18). Moreover, it was demonstrated that TAC is a prodrug that requires activation by the mycobacterial monooxygenase EthA (19). Following EthA activation, TAC inhibits cyclopropanation of mycolic acids, resulting in the loss of α-mycolates (18). However, this modification in the mycolic acid composition cannot entirely explain the bacteriostatic activity of TAC. Indeed, we recently demonstrated that in addition to EthA, MmaA4, an S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferase necessary for the synthesis of oxygenated mycolates and M. tuberculosis virulence (20, 21), is required for the biotransformation of TAC (or EthA-activated TAC) into a biologically active metabolite(s) whose target(s) has yet to be identified. Point mutations or disruption of mmaA4 in M. tuberculosis resulted in high levels of TAC resistance. On the other hand, overexpression of MmaA4 resulted in increased susceptibility to the drug, leading to the hypothesis that MmaA4 may also participate in the activation process of TAC (17). Importantly, these studies on TAC were the first demonstration of the participation of an enzyme linked to the synthesis of oxygenated mycolates in a drug activation process in M. tuberculosis, thereby highlighting the interplay between mycolic acid synthesis, drug activation, and mycobacterial virulence.

The mode of action of TAC still remains poorly understood, a view that is supported by the fact that multiple M. bovis BCG and M. tuberculosis mutants highly resistant to TAC could be selected despite the presence of wild-type ethA and mmaA4 genes (data not shown). This implies that TAC is acting on multiple and yet unidentified targets. Therefore, this study was undertaken to investigate whether this drug affects other molecules that may be related to mycolic acids with the hope that it may also uncover novel cell wall-associated components that have been overlooked in previous studies.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mycobacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

M. bovis BCG strain Pasteur, Mycobacterium thermoresistibile, Mycobacterium scrofulaceum, and Mycobacterium smegmatis were grown on Middlebrook 7H10 agar plates supplemented with 10% oleic acid, albumin, dextrose, catalase (Difco). M. tuberculosis mc27000, an unmarked version of mc26030 (22), was grown in 7H10/oleic acid, albumin, dextrose, catalase containing 20 μg/ml pantothenic acid. The M. bovis BCG R2 mutant resistant to TAC and carrying the G85D mutation was grown in medium supplemented with 25 μg/ml kanamycin (17). All liquid cultures were performed at 37 °C in Sauton's medium or in a modified medium in which glycerol had been replaced by 2 g/liter glucose when required.

Glycolipid Extraction and Analysis

Apolar and polar lipids were extracted according to established procedures (23). Apolar glycolipids were further purified on a solid phase extraction column (HyperSepFlorisil, Thermo scientific) eluted with chloroform, chloroform/methanol (2:1, v/v), chloroform/methanol (1:1, v/v), and chloroform/methanol/water (1:2:0.8, v/v/v). Glycolipids of interest (phenolic glycolipid (PGL), trehalose dimycolate (TDM), and dimycolyl diarabinoglycerol (DMAG)) were eluted with chloroform/methanol (2:1, v/v). Apolar and polar lipid extracts were examined by one-dimensional high performance thin layer chromatography (HPTLC) of glass-backed Silica Gel 60 (Merck) run in chloroform/methanol/(96:4, v/v) and chloroform/acetic acid/methanol/water (40:25:3:6, v/v/v/v), respectively. Glycolipids were visualized by spraying plates with the orcinol/sulfuric acid reagent (0.2% (w/v) orcinol in H2SO4/water (1:4, v/v)) followed by charring.

Purification of DMAG and Mycolates

To purify DMAG, the crude apolar extract was dissolved in chloroform and fractionated by flash chromatography on a silica gel column. The column was then eluted with chloroform (500 ml) and chloroform/methanol with increasing volumes of methanol (1–50%). Purification of DMAG was monitored by one-dimensional HPTLC using chloroform/methanol (96:4, v/v) as the running solvent. Glycolipids were visualized by spraying plates with orcinol/sulfuric acid reagent after heating the plates at 120 °C. DMAG was then eluted into fractions containing 5–7% methanol. DMAG-containing fractions were pooled and applied to Florisil® column chromatography (Acros Organics). Elution was performed with chloroform (500 ml) followed by chloroform/methanol with increasing concentrations of methanol (2–20%). As mentioned above, the purification process was monitored by HPTLC and DMAG was visualized after spraying the plates with orcinol/sulfuric acid. DMAG was eluted into fractions containing 7% methanol. DMAG-containing fractions were pooled and subjected to structural analysis.

Extraction of mycolic acid methyl esters was carried out as described previously (24). Briefly, purified DMAG or TDM was subjected to alkaline hydrolysis in 1 ml of 15% tetrabutylammonium hydroxide overnight at 100 °C. After cooling, free mycolic acids were methyl-esterified by additions of 2 ml of dichloromethane, 150 μl of iodomethane, and 1 ml of water. The mixture was sonicated and then centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 10 min. The aqueous phase was discarded, and the dichloromethane phase containing mycolic acid methyl esters was washed three times with 2 ml of water. Finally, the organic phase was evaporated under a stream of nitrogen, and the sample was diluted in chloroform prior to mass spectrometry analysis.

Chemical Procedures

DMAG was de-O-acylated in chloroform/methanol (2:1, v/v) containing 0.1 m NaOH at 37 °C for 2 h. After evaporation, the resulting oligosaccharide was dissolved in water and further purified on a carbograph solid phase extraction column (Alltech). Prior to injection in gas-liquid chromatography, the oligosaccharide was per-O-acetylated with acetic anhydride and pyridine at 100 °C for 4 h. The reagent was removed under a stream of nitrogen, and the sample was dissolved in chloroform.

The sugar composition of DMAG was analyzed by gas-liquid chromatography after heptafluorobutyrate derivatization of the sample (25). Briefly, the sample containing the internal standard (0.2–2 mg of lysine) was lyophilized and incubated with 0.5 ml of methanol, 0.5 m HCl at 80 °C for 20 h. After methanolysis, the sample was evaporated to dryness under a light stream of nitrogen followed by the addition of 200 μl of acetonitrile and 25 μl of heptafluorobutyric anhydride. The mixture was heated at 150 °C for 5 min. After cooling, the sample was evaporated under a stream of nitrogen, diluted in the appropriate volume of dry acetonitrile, and injected in a gas-liquid chromatograph coupled to a mass spectrometer.

Gas-Liquid Chromatography Coupled to Mass Spectrometry

Gas chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis was performed using a Carlo Erba GC 8000 gas chromatograph equipped with a 25-m × 0.32-mm CP-Sil5 CB low bleed/MS capillary column (0.25-μm film phase; Chrompack). The temperature of the Ross injector was 280 °C. The per-O-acetylated molecule was analyzed using a temperature program that was started at 120 °C, increased to 300 °C at 10 °C/min, and maintained at 300 °C for 30 min. Heptafluorobutyryl derivative monosaccharides were analyzed using a temperature program that was started at 100 °C, increased to 140 °C at 1.2 °C/min, and ramped at 4 °C/min until 240 °C. Electron ionization mass spectra were obtained using a Finnigan Automass II mass spectrometer.

Matrix-assisted Laser Desorption Ionization-Mass Spectrometry (MALDI-MS) Analysis

The molecular masses of glycolipids were measured by MALDI-TOF on a Voyager Elite reflectron mass spectrometer (PerSeptive Biosystems, Framingham, MA) equipped with a 337 nm UV laser. Samples were prepared by mixing in the tube 5 μl of chloroform-diluted glycolipid/lipid solution and 5 μl of 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid matrix solution (10 mg/ml dissolved in chloroform/methanol (1:1, v/v). The mixtures (2 μl) were then spotted on the target plate.

NMR Analysis

NMR experiments were recorded at 300 K on Bruker 400, 600, and 900 Avance spectrometers equipped with a 5-mm broad band inverse probe and a 5-mm triple resonance cryoprobe, respectively. Prior to NMR spectroscopic analyses, lipids/glycolipids were repeatedly exchanged in CDCl3/CD3OD (2:1, v/v) (99.97% purity; Euriso-top, Saint-Aubin, France) with intermediate drying, finally dissolved in CDCl3, and transferred to standard or Shigemi (Allison Park, PA) tubes. Glycan obtained after de-O-acylation of DMAG was repeatedly exchanged in 2H2O (99.97% 2H; Euriso-top) with intermediate freeze drying, finally dissolved in 2H2O, and transferred to a Shigemi tube. Samples used in light water contained 10% 2H2O. Chemical shifts (ppm) were calibrated using the tetramethylsilane signal (δ1H/δ13C 0.000 ppm) in CDCl3 or acetone (δ1H 2.225/δ13C 31.55 ppm) in 2H2O as internal references. The COSY, TOCSY, 1H-13C HSQC, and 1H-13C HMBC experiments were performed using the Bruker standard sequences.

RESULTS

Treatment with TAC Is Associated with Decreased Production of Apolar Glycolipid

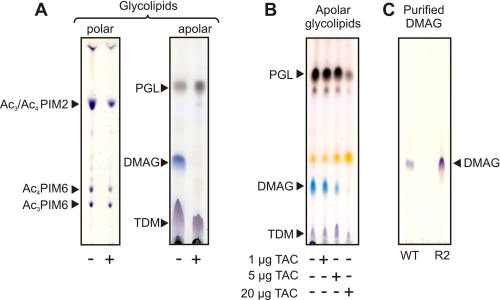

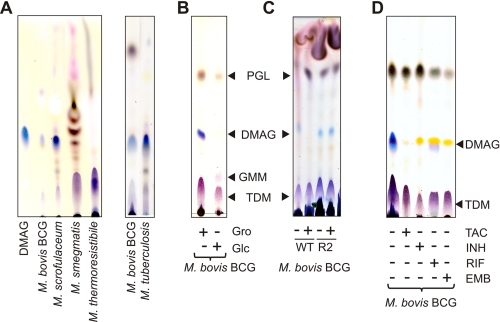

We previously demonstrated that TAC and its related structural analogues prevented cyclopropanation of mycolic acids in M. bovis BCG and Mycobacterium marinum by inhibiting the S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferases PcaA, MmaA2, and CmaA2 (17–19). In addition, a majority of TAC-resistant mutants lacked ketomycolic acids due to lesions within the gene encoding the methyltransferase MmaA4, an enzyme required for the synthesis of keto- and methoxymycolic acids (17, 20, 21). Although important, these modifications are unlikely to explain the bacteriostatic activity of TAC on their own. This prompted us to extend our initial studies and to examine whether TAC affects the biosynthesis of cell wall-associated glycolipids. We first analyzed the glycolipid profile in M. bovis BCG treated or not with high doses of TAC (5 μg/ml). Comparison of polar glycolipids by TLC analysis failed to reveal significant differences between the untreated and treated cultures. An overall small scale decrease in the quantity of phosphatidyl-myo-inositol mannosides was observed in TAC-treated bacteria, but relative intensities of each individual spot did not vary (Fig. 1A). The nature of each phosphatidyl-myo-inositol mannoside subspecies was further confirmed by two-dimensional TLC using authentic standard molecules (data not shown) (23, 26). These results indicate that TAC has a moderate influence on the biosynthesis of phosphatidyl-myo-inositol mannosides. In sharp contrast, the apolar glycolipid profiles were significantly different between the untreated and TAC-treated cultures (Fig. 1A). Of notable interest was the disappearance of a major compound in the drug-treated bacilli that migrated with a polarity intermediate between PGL and TDM, which were not affected by TAC treatment (Fig. 1A). This glycolipid could easily be traced based on its pentose-specific blue color, which contrasted with the purple and brown colors characterizing the other glycolipids after staining with orcinol (27). However, based on its chromatographic and staining behaviors, we were unable to identify the nature of this unknown glycoconjugate.

FIGURE 1.

Cell wall-associated glycolipid profile in mycobacteria following treatment with TAC. Apolar and polar lipids/glycolipids were extracted from mycobacteria and analyzed by HPTLC using chloroform/methanol (96:4, v/v) and chloroform/acetic acid/methanol/water (40:25:3:6, v/v/v/v) as running solvents, respectively. Glycolipids were stained by orcinol/sulfuric acid. A, exposure to TAC (5 μg/ml) for 5 days is correlated with decreased production of a major apolar glycolipid (DMAG) in M. bovis BCG. The overall production of polar glycolipids was slightly decreased, but the relative amounts of individual components did not vary. B, increasing concentrations of TAC (from 1 to 20 μg/ml) correlated with decreased production of DMAG in a dose-dependent manner in M. marinum. C, DMAG was purified from M. bovis BCG WT and R2 strains for structural analysis. Their purity was assessed by HPTLC. PIM, phosphatidylinositol mannoside. Results presented are representative of two independent experiments.

We next tested whether TAC treatment of M. marinum, a close relative of M. tuberculosis (28) that shows better tolerance to the drug, also influenced the lipid profile in a similar way. Indeed, we observed a large amount of the glycolipid in M. marinum, which remained fully responsive to TAC (Fig. 1B). The inhibition followed a dose-dependent pattern similar to what was observed in M. bovis BCG (Fig. 1B). This indicates that the effect of TAC on the levels of this glycolipid was not restricted to M. bovis BCG.

Apolar Glycolipid Contains Mycolic Acids

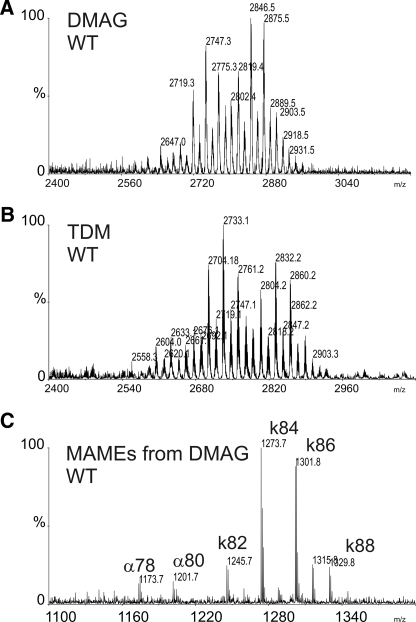

The structure of the unknown glycolipid was then determined using a combination of MS, GC, and NMR spectroscopy. Prior to structural analyses, it was purified from the apolar glycolipid extract by two successive adsorption chromatographies using 5–7% methanol in chloroform. The purity of the sample was assessed by TLC and sulfuric acid/orcinol staining (Fig. 1C). The MALDI-TOF-MS spectrum of the purified compound revealed a series of [M + Na]+ signals exhibiting a profile very similar to the TDM purified from the apolar glycolipid fraction (Fig. 2, A and B), strongly suggesting that it is substituted by mycolic acids. This hypothesis was confirmed by mass spectrometry analysis of the methyl-esterified lipid moiety released from the glycolipid by alkaline hydrolysis. A rather homogenous profile of α- and ketomycolates dominated by two signals at m/z 1273 and 1301 attributed to [M + Na]+ adducts of C84 and C86 ketomycolates (Fig. 2C). This composition fully agrees with the published mycolate composition of mycolic acids purified from TDM of M. bovis BCG Pasteur and confirms that both glycolipids share a similar, perhaps identical, lipid moiety but differ with respect to their glycan domain (29).

FIGURE 2.

Mass spectrometry analysis of DMAG and TDM. A, MALDI-MS spectrum of DMAG showing a series of peaks corresponding to TDM (shown in B) but with an average difference of +14 units. C, identification of lipid moiety by MALDI-MS after de-O-acylation indicates that DMAG is substituted by mycolic acids. MAMEs, mycolic acid methyl esters; k, ketomycolic acid methyl esters; α, α-mycolic acid methyl esters.

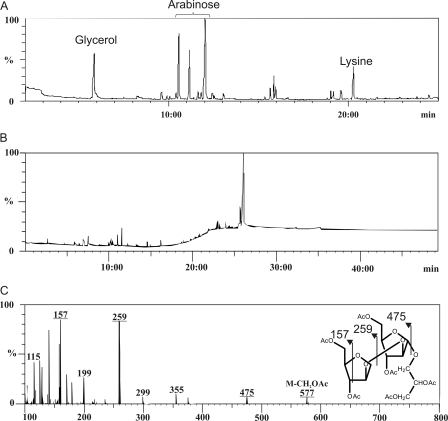

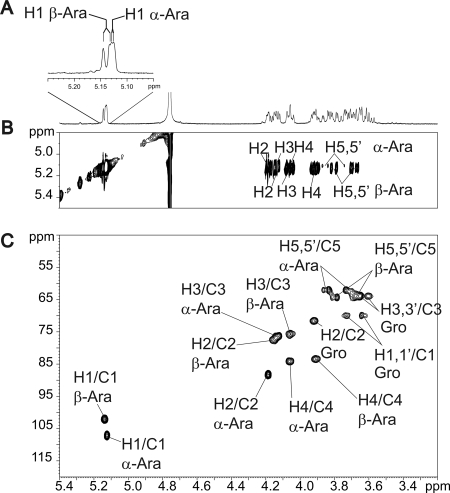

Glycan Moiety of Apolar Glycolipid Is β-Araf-(1→2)-α-Araf-(1→1)-Gro

Monosaccharide analysis of the de-O-acylated glycolipid indicated that it comprises arabinose and glycerol (Fig. 3A). GC/MS analysis of the de-O-acylated per-O-acetylated compound revealed a single total ion count signal around 26 min that was identified by electronic impact-MS fragmentation as Pent-Pent-Gro (where Pent is pentose and Gro is glycerol), thus establishing the carbohydrate sequence as arabinose-arabinose-glycerol (Ara-Ara-Gro) (Fig. 3B and 3C). The fine structure of the glycolipid was elucidated by 1H homonuclear and 1H/13C heteronuclear NMR experiments. The sequence of the sugar moiety was first determined on de-O-acylated compound to remove the eventual interferences caused by the lipid moiety (Fig. 4). The one-dimensional 1H NMR spectrum showed two distinct anomer signals at 5.12 and 5.13 ppm indicative of the presence of two monosaccharides (Fig. 4A). Based on their spin systems and vicinal coupling constant patterns obtained by two-dimensional 1H-1H TOCSY and 1H-13C HSQC NMR experiments, the two monosaccharides were identified as two arabinose residues (Ara) (Fig. 4, B and C, and Table 1) (30, 31). The C4 chemical shift values of both residues superior to 80 ppm typified furanose conformation (Araf). According to their 1H/13C chemical shifts and 3JH1/H2 coupling constants, the values permitted us to distinguish the presence of α-Araf (H1/C1 δ 5.12/107.1; 3JH1/H2 = 2.0 Hz) and β-Araf (H1/C1 δ 5.13/102.4; 3JH1/H2 = 4.7 Hz) (Table 1). The deshielding of α-Araf-C2 (Δδ = +6.4) compared with that of a non-reducing terminal α-Araf established that this residue was substituted in position C2. In addition to monosaccharides signals, the spin system of a Gro moiety was identified in all NMR experiments. The split Gro-H1,H1′ signals and deshielding (Δδ = +6.0) of Gro-C1 compared with H3/C3 demonstrated that the C1 position was substituted. Altogether, data from GC/MS and NMR experiments identified the sugar moiety as β-Araf-(1→2)-α-Araf-(1→1)-Gro. The positions of acylation by mycolic acids were assigned by NMR analysis of intact glycolipid (data not shown) and by comparing the 1H/13C NMR chemical shifts of Araf and Gro residues of intact and de-O-acylated glycolipids. As summarized in Table 1, the strong deshielding of β-Araf-H5/5′ (Δδ = +0.74/0.54) and α-Araf-H5/5′ (Δδ = +0.65/0.53) coupled to the β effect on β/α-Araf-C4 (Δδ = −4/−3.3) clearly established that the C5 positions of both Araf residues were substituted by mycolic acids. Taken collectively, these data identified the unknown glycolipid as 5-O-mycolyl-β-Araf-(1→2)-5-O-mycolyl-α-Araf-(1→1)-Gro, referred to as DMAG (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 3.

GC/MS analysis of carbohydrate moiety of de-O-acylated DMAG. A, composition analysis establishes the presence of glycerol and arabinose. Lysine was used as internal standard. B, gas-liquid chromatogram of per-O-acetylated oligosaccharide showing a single intense peak at retention time 26 min. C, its electrospray ionization fragmentation pattern identifies the glycan sequence of DMAG as pentose-pentose-glycerol. Together with the sugar composition obtained by GC analysis, the DMAG carbohydrate sequence was deduced as Ara-Ara-Gro.

FIGURE 4.

NMR analysis of de-O-acylated DMAG. One-dimensional 1H (A), 1H/1H TOCSY (B), and 1H/13C HSQC (C) spectra of de-O-acylated DMAG establish its glycosidic sequence as β-Araf-(1→2)-α-Araf-(1→1)-Gro. Further NMR experiments on native DMAG (Table 1) identified its structure as 5-O-mycolyl-β-Araf-(1→2)-5-O-mycolyl-α-Araf-(1→1)-Gro (DMAG).

TABLE 1.

1H and 13C chemical shifts of de-O-acylated and intact 5-O-mycolyl-β-Araf-(1→2)-5-O-mycolyl-α-Araf-(1↔1′)-Gro isolated from M. bovis BCG

The bold values correspond to the substitution positions of the α-Araf residue.

| De-O-acylated DMAG |

Native DMAG |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1/C1 | H2/C2 | H3/C3 | H4/C4 | H5/C5 | H1/C1 | H2/C2 | H3/C3 | H4/C4 | H5/C5 | |

| β-Araf | 5.13/102.4 | 4.14/77.4 | 4.05/75.6 | 3.90/83.4 | 3.79, 3.66/64.1 | 5.02/101.1 | 4.07/76.4 | 4.06/77.2 | 4.09/79.4 | 4.53, 4.20/64.7 |

| α-Araf | 5.12/107.1 | 4.18/88.2 | 4.12/76.2 | 4.06/84.0 | 3.84, 3.73/62.0 | 4.98/105.4 | 4.08/87.6 | 4.06/76.4 | 4.17/80.7 | 4.49, 4.26/62.5 |

| Glycerol (Gro) | 3.73, 3.64/69.8 | 3.91/71.4 | 3.60, 3.69/63.8 | 3.74, 3.62/69.8 | 3.83/70.1 | 3.67, 3.62/62.9 | ||||

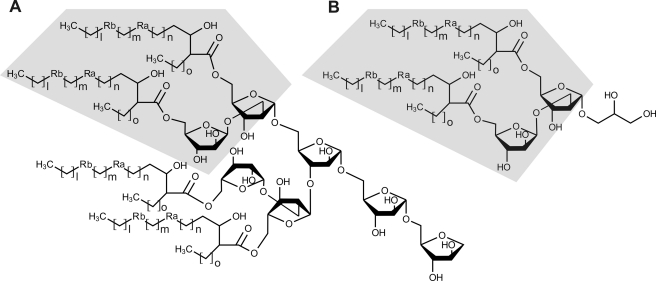

FIGURE 5.

Structural comparison of DMAG and mAGP. The 5-O-mycolyl-β-Araf-(1→2)-5-O-mycolyl-α-Araf motif is found in the terminal non-reducing end of mAGP (A) and in DMAG (B). In wild-type M. bovis BCG, Ra is cis- and trans-cyclopropanes, Rb is cis-cyclopropane and ketone; in the TAC-resistant R2 mutant, Ra is cis- and trans-cyclopropanes, and Rb is cis-cyclopropane.

Distribution of DMAG in Mycobacteria

Descriptions of DMAG in the literature remain scarce. To our knowledge, since Minnikin and co-workers (32–34) identified it two decades ago in the M. avium-Mycobacterium intracellulare complex, M. scrofulaceum, and Mycobacterium kansasii, it has not been mentioned in the literature. In contrast to our study, the authors failed to detect DMAG in M. bovis BCG (32–34). This prompted us to analyze the occurrence and distribution of DMAG in several mycobacterial species, including M. tuberculosis. As shown in Fig. 6A, DMAG was observed in the slow growing species M. bovis BCG, M. tuberculosis, and M. scrofulaceum. In contrast, we failed to detect DMAG in the fast growing species M. smegmatis, M. thermoresistibile (Fig. 6A), Mycobacterium chelonae, and Mycobacterium xenopi (data not shown). Although not observed, we cannot exclude that DMAG may be present in small amounts in these species but below the detection threshold of the methods used. The presence of DMAG in M. tuberculosis along with M. bovis BCG is in clear contradiction with previous literature. One explanation may arise from growth culture conditions that drastically influence the synthesis of surface glycoconjugates. To check whether the culture medium modulates/affects DMAG production, synthesis of DMAG was assessed in M. bovis BCG grown either in glycerol-containing medium (Sauton) or in a glucose-containing medium (Sauton in which glycerol has been replaced by 2 g/liter glucose). As shown in Fig. 6B, bacteria grown in the standard Sauton's medium allowed M. bovis BCG to produce DMAG, whereas replacement of glycerol by glucose in the modified Sauton's medium decreased the production of DMAG below the detection level. However, the glucose-containing medium allowed M. bovis BCG to produce another apolar glycolipid that migrates above TDM and that was subsequently identified by MS as a glucose monomycolate as recently reported in M. avium (Fig. 6B and data not shown) (35). Taken together, these results indicate that DMAG is present in various mycobacterial species and particularly in large quantities in slow growing species such as M. tuberculosis.

FIGURE 6.

Expression of other mycobacterial species. Apolar lipids were extracted from mycobacteria and analyzed by HPTLC. DMAG and other glycolipids were stained by orcinol/sulfuric acid. A, DMAG was identified in slow growing mycobacteria, including M. tuberculosis, M. marinum, M. bovis BCG, and M. scrofulaceum, but not in the fast growing M. smegmatis. B, DMAG production is strongly reduced in M. bovis BCG grown in glycerol-free medium. The presence of glucose (2 g/liter), used as the only carbon source, stimulated production of glucose monomycolate (GMM). C, DMAG production is decreased in M. bovis BCG WT after 5 days of exposure to TAC (5 μg/ml) but not in M. bovis BCG R2 strain. D, M. bovis BCG cultures were treated with different antitubercular drugs for 5 days at the following concentrations: 2.5 μg/ml TAC, 0.5 μg/ml INH, 10 μg/ml EMB, and 1 μg/ml rifampicin (RIF). Drugs that target mAGP, such as INH or EMB, also inhibit the production of DMAG, suggesting a metabolic relationship between the two compounds. Results presented are representative of two independent experiments.

Inhibition of DMAG Production Requires Functional MmaA4 Mycolic Acid Methyltransferase

The S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferase MmaA4 involved in the synthesis of oxygenated mycolic acids was shown to be necessary for TAC susceptibility in M. bovis BCG and M. tuberculosis (17, 36). Because overexpression of a functional MmaA4 was correlated with increased susceptibility to TAC, it was also proposed that MmaA4 participates in the activation process of TAC (17). Several TAC-resistant M. bovis BCG strains were characterized by a strongly altered mycolic acid profile lacking oxygenated mycolates and the presence of genetic lesions within the mmaA4 gene. In particular, we identified a missense mutation (G85D) located within the S-adenosylmethionine binding site caused by a G254A substitution in an M. bovis BCG mutant designated R2 (17). We reasoned that this particular mutant could be very useful to investigate whether the inhibition of DMAG production requires MmaA4-dependent activation of TAC. Similarly to the wild-type strain, the R2 mutant exhibited the presence of DMAG (Fig. 1C). The structural analysis by MS and NMR indicated that DMAG purified from the R2 strain exhibited a glycan moiety identical to WT but substituted by α-mycolic acids with reduced cyclopropanation and ketomycolate (data not shown). In contrast to the parental strain, DMAG production was not inhibited in R2 following exposure to 10 μg/ml TAC, indicating that a functional MmaA4 is required for the drug to inhibit DMAG production (Fig. 6C).

TAC Interferes with mAGP Metabolism

Because the structure of the DMAG is highly reminiscent of that of the terminal 5-mycoloyl-β-Araf-(1→2)-5-mycoloyl-α-Araf-(1→3,5) motif capping mAGP, we hypothesized the existence of a metabolic relationship between these two compounds. We therefore examined whether drugs known to interfere with mAGP biosynthesis would also affect DMAG synthesis. As shown on Fig. 6D, the treatment of M. bovis BCG with INH (0.5 μg/ml), a drug primarily targeted toward the synthesis of mycolates (37), decreased the production of DMAG. In addition, INH partially inhibited the biosynthesis of TDM, a well known mycolic acid-containing glycolipid, whereas TAC (2.5 μg/ml) did not affect TDM synthesis. The treatment of M. bovis BCG with EMB (10 μg/ml), a drug inhibiting the synthesis of the arabinan moiety of the mAGP but not that of mycolic acids, was accompanied by a total suppression of DMAG production and a partial loss of PGL (Fig. 6D) (38). Considering that EMB affects the synthesis of mAGP, which constitutes a matrix in which other mycobacterial glycolipids are interspersed, it is difficult to establish whether the reduction of PGL results from a direct effect of EMB or from a disturbance of the cell wall architecture (39, 40). In contrast, rifampicin (1 μg/ml), an inhibitor of transcription, induced a general decrease of cell wall components but did not modify the ratios of individual glycolipids. Overall, these results strongly suggest that mAGP and DMAG may be metabolically interconnected.

DISCUSSION

The present study originated from the initial observation of the disappearance of a major apolar glycolipid in M. bovis BCG and M. marinum cell extracts following exposure to TAC, a second line anti-TB drug whose mode of action remains elusive. The unique chromatographic properties of this compound, including (i) a TLC mobility that is intermediate between PGL and TDM and (ii) a blue color induced by sulfuric acid/orcinol staining, did not fit with those of glycolipids usually identified in these species. Starting from this observation, the present study demonstrated the following. (i) This compound, 5-O-mycolyl-β-Araf-(1→2)-5-O-mycolyl-α-Araf-(1→1)-Gro (DMAG) (Fig. 5), is a glycolipid very poorly described in mycobacteria. (ii) DMAG was produced in various mycobacterial species, including M. tuberculosis. (iii) Exposure to TAC correlated with decreased DMAG production in mycobacteria, and this effect was dependent on a functional MmaA4. (iv) DMAG production requires the presence of glycerol in the culture medium. Furthermore, inhibition of DMAG by drugs inhibiting mAGP is consistent with the strong structural analogy between the two components, thereby raising a possible metabolic interconnectivity between DMAG and mAGP.

In a seminal series of studies, Minnikin and co-workers (32–34) identified DMAG in the M. avium-M. intracellulare complex, but the study of its biosynthesis and function have been completely neglected over the last two decades, being, to the best of our knowledge, only mentioned by its discoverers. These authors failed to identify DMAG in M. bovis BCG (strains Glaxo F10, Pasteur 1173P2, and Tokyo 172) or M. tuberculosis (strain H37Rv). One obvious explanation to the discrepancy could be the method and solvents used for glycolipid extraction. In their experiments, the investigators extracted DMAG using a biphasic solution of hexane/methanol/water (1:0.05:0.45, v/v/v), whereas our study included a less polar biphasic solution made of petroleum ether/methanol/water (1:0.9:0.1, v/v/v) (32–34). A second explanation may rely on differences in growth and culture conditions that are known to drastically influence the synthesis of bacterial surface glycoconjugates, including glycolipids (35) and polysaccharides (41). A relevant example is the synthesis of glucose monomycolate, which is up-regulated in M. avium by the presence of glucose in the growth environment (35). This point is also emphasized in our study: the replacement of glycerol with glucose strongly reduced the production of DMAG and stimulated the production of glucose monomycolate. These observations strengthen the extreme versatility of the mycobacterial glycolipid biosynthetic machinery. In addition to the source of carbon used to grow mycobacteria, DMAG production may also be dependent on the growth phase and may explain why DMAG has been overlooked by many investigators. Nevertheless, as demonstrated earlier, DMAG is produced during M. avium infection because these patients had very high anti-DMAG antibody titers (33). In the same study, the authors failed to detect anti-DMAG IgM antibodies in patients with active TB; albeit specific IgG titers were detected in 25% of the patients (33). This supports the view that DMAG is produced during infection with M. tuberculosis and implies that DMAG is a surface-exposed and immunogenic molecule. Therefore, one can presume that this glycolipid is also synthesized during TB infection. The distinct anti-DMAG antibody titers in M. avium- and M. tuberculosis-infected patients may reflect a quantitative difference of DMAG synthesis in these two pathogens. Accordingly, taking the TDM as reference, we observed by TLC that M. scrofulaceum, a close relative of M. avium, produced about 10 times more DMAG than M. bovis BCG and M. tuberculosis (Fig. 6A). Whether this glycolipid is preferentially produced in replicating bacteria or under dormancy also awaits further investigation.

The obvious structural similarity between DMAG and the non-reducing terminus of mAGP (Fig. 5) emphasizes the potential metabolic relationship between these two components. The total inhibition of DMAG production by EMB was a clear indication that the synthesis of the mAGP polysaccharide moiety is somehow linked to the production of DMAG. In this context, either the terminal motif of mAGP and DMAG share the same biosynthetic route and are simultaneously produced, or DMAG originates from the catabolism of the already synthesized mAGP. Three putative arabinosyltransferases, AftB, AftC, and AftD, have so far been implicated in the synthesis of the terminal β-Araf-(1→2)-α-Araf-(1→3) motif of mAGP (42–44). If DMAG and mAGP share these enzymes, the synthesis of DMAG may be primed by the transfer of α-Araf by any α-arabinosyltransferase onto glycerol, elongated by the action of a β-arabinosyltransferase (AftB is so far the only enzyme presenting this activity), and completed by the transfer of mycolic acids via the Ag85 complex. To visualize the dynamics of mycolylation of DMAG, we attempted to radiolabel the DMAG using [14C]acetate that is readily incorporated during mycolic acid biosynthesis. Unexpectedly, using a standard mycolic acid labeling procedure, we failed to visualize the DMAG after lipid extraction and TLC separation (data not shown). In contrast, other mycolic acid-containing glycolipids, such as TDM, and total cell wall mycolic acids could be visualized by TLC-autoradiography. This suggests that DMAG was not synthesized along with other lipids/glycolipids. Absence of labeling, however, is compatible with the release of 5-O-mycolyl-β-Araf-(1→2)-5-O-mycolyl-α-Araf from preformed mAGP and transfer onto an exogenous substrate, such as glycerol. McNeil and co-workers (46) have reported the existence in M. smegmatis of an endogenous endoarabinanase activity that can release soluble oligoarabinosides from AGP. Analysis of the in vitro reaction products by mass spectrometry identified Ara7, Ara18, and Ara19 through cleavage of the α-Araf-(1→5)-α-Ara glycosidic linkage (47). However, the glycolytic activity was assessed against mycolylated arabinan, and the corresponding enzyme has not yet been identified. From a totally independent source, an exo-1,5-α-l-arabinanase has been isolated from Penicillium chrysogenum. The enzyme was shown to exhibit a transglycosylation activity from the non-reducing terminus of α-1,5-l-arabinan toward a wide range of aliphatic alcohols. Interestingly, among those, glycerol appeared to be the best acceptor for the enzyme and generated α-l-Araf-(1→5)-α-l-Araf-(1→1)-Gro, which is highly reminiscent of the structure described in the present study (48). Although such an enzyme has never been identified in a mycobacterial species, it is very tempting to speculate that mycobacteria possess the ability to express an exoarabinanase with transglycosylation activity able to release 5-O-mycolyl-β-Araf-(1→2)-5-O-mycolyl-α-Araf from the mAGP and transfer it to an endo- or exogenous substrate. Such an activity would if it exists provide a first proof for the mAGP turnover, opening the way for novel strategies for inhibiting mycobacterial growth.

Previously, we demonstrated that TAC alters the biosynthesis of mycolic acids, which are essential AGP substituents in mycobacteria (17, 18). In this study, we demonstrated that a functional MmaA4 is needed for TAC to interfere with the production of a mycobacterial cell wall glycolipid structurally linked to the mAGP. However, the present work does not allow us to establish whether the reduction in the level of DMAG is a direct or an indirect consequence of TAC action. In addition, it is not known whether this effect on DMAG contributes to the growth-inhibitory effect of TAC. These important questions await future studies.

This study also raises questions about the possible biological functions associated with DMAG. Indeed, given the high structural analogy with TDM as well as its localization to the cell wall (presumably cell surface-exposed), one can hypothesize that DMAG may share with TDM several elements of M. tuberculosis pathogenesis, such as proinflammatory cytokine production, granuloma formation, and tissue-destructive lesions. Moreover, we have recently shown that mycobacterial biofilms are formed through genetically programmed pathways and built upon a large abundance of novel extracellular free mycolic acids, which are produced through enzymatic release from newly synthesized TDM by a specific TDM hydrolase (45). Whether DMAG represents another source of free mycolates during biofilm formation remains an attractive hypothesis to be addressed.

Acknowledgments

The 800 and 900 MHz spectrometers were funded by Région Nord-Pas de Calais, European Union (Fonds Euroṕeen de Développement Régional), Ministère Français de la Recherche, Université Lille1-Sciences et Technologies, and CNRS. The 600 MHz facility used in this study was funded by the European Union, Région Nord-Pas de Calais, CNRS, and Institut Pasteur de Lille.

This study was supported by French National Research Agency Grant ANR-05-MIIM-025 (to Y. G. and L. K.), a grant from the Ministère de l'Enseignement Supérieur (to Y. R.), Trés Grand Equipment de Résonance Magnétique Nucléaire à Très Hauts Champs Grant Fr3050 (for conducting the research on the 800 and 900 MHz spectrometers), and the Association Nationale de la Recherche et de la Technologie and Bio-Rad Laboratories (to B. B.).

- TB

- tuberculosis

- Ara

- arabinose

- DMAG

- dimycolyl diarabinoglycerol

- EMB

- ethambutol

- Gro

- glycerol

- HMBC

- heteronuclear multiple bound correlation

- HPTLC

- high performance thin layer chromatography

- INH

- isoniazid

- mAGP

- mycolyl-arabinogalactan-peptidoglycan

- PGL

- phenolic glycolipid

- TAC

- thiacetazone

- TDM

- trehalose dimycolate

- TOCSY

- total correlation spectroscopy

- BCG

- Bacille Calmette-Guérin

- AGP

- deacylated mAGP

- mAGP

- mycolyl-arabinogalactan-peptidoglycan

- HSQC

- heteronuclear single quantum correlation.

REFERENCES

- 1. Brennan P. J., Nikaido H. (1995) The envelope of mycobacteria. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 64, 29–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Daffé M., Draper P. (1998) The envelope layers of mycobacteria with reference to their pathogenicity. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 39, 131–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kremer L., Baulard A., Besra G. S. (2000) in Molecular Genetics of Mycobacteria (Hatfull G. F., Jacobs W. R., Jr., eds) pp. 173–190, ASM Press, Washington, D. C [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zuber B., Chami M., Houssin C., Dubochet J., Griffiths G., Daffé M. (2008) Direct visualization of the outer membrane of mycobacteria and corynebacteria in their native state. J. Bacteriol. 190, 5672–5680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hoffmann C., Leis A., Niederweis M., Plitzko J. M., Engelhardt H. (2008) Disclosure of the mycobacterial outer membrane: cryo-electron tomography and vitreous sections reveal the lipid bilayer structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 3963–3967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Takayama K., Wang C., Besra G. S. (2005) Pathway to synthesis and processing of mycolic acids in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 18, 81–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Haites R. E., Morita Y. S., McConville M. J., Billman-Jacobe H. (2005) Function of phosphatidylinositol in mycobacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 10981–10987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Neyrolles O., Guilhot C. (2011) Recent advances in deciphering the contribution of Mycobacterium tuberculosis lipids to pathogenesis. Tuberculosis 91, 187–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Karakousis P. C., Bishai W. R., Dorman S. E. (2004) Mycobacterium tuberculosis cell envelope lipids and the host immune response. Cell. Microbiol. 6, 105–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vilchèze C., Jacobs W. R., Jr. (2007) The mechanism of isoniazid killing: clarity through the scope of genetics. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 61, 35–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Telenti A., Philipp W. J., Sreevatsan S., Bernasconi C., Stockbauer K. E., Wieles B., Musser J. M., Jacobs W. R., Jr. (1997) The emb operon, a gene cluster of Mycobacterium tuberculosis involved in resistance to ethambutol. Nat. Med. 3, 567–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Davidson P. T., Le H. Q. (1992) Drug treatment of tuberculosis—1992. Drugs 43, 651–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Houston S., Fanning A. (1994) Current and potential treatment of tuberculosis. Drugs 48, 689–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Caminero J. A., Sotgiu G., Zumla A., Migliori G. B. (2010) Best drug treatment for multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. Lancet. infect. Dis. 10, 621–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nunn P., Porter J., Winstanley P. (1993) Thiacetazone—avoid like poison or use with care? Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 87, 578–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bermudez L. E., Reynolds R., Kolonoski P., Aralar P., Inderlied C. B., Young L. S. (2003) Thiosemicarbazole (thiacetazone-like) compound with activity against Mycobacterium avium in mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47, 2685–2687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Alahari A., Alibaud L., Trivelli X., Gupta R., Lamichhane G., Reynolds R. C., Bishai W. R., Guerardel Y., Kremer L. (2009) Mycolic acid methyltransferase, MmaA4, is necessary for thiacetazone susceptibility in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol. Microbiol. 71, 1263–1277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Alahari A., Trivelli X., Guérardel Y., Dover L. G., Besra G. S., Sacchettini J. C., Reynolds R. C., Coxon G. D., Kremer L. (2007) Thiacetazone, an antitubercular drug that inhibits cyclopropanation of cell wall mycolic acids in mycobacteria. PLoS One 2, e1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dover L. G., Alahari A., Gratraud P., Gomes J. M., Bhowruth V., Reynolds R. C., Besra G. S., Kremer L. (2007) EthA, a common activator of thiocarbamide-containing drugs acting on different mycobacterial targets. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51, 1055–1063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dubnau E., Chan J., Raynaud C., Mohan V. P., Lanéelle M. A., Yu K., Quémard A., Smith I., Daffé M. (2000) Oxygenated mycolic acids are necessary for virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mice. Mol. Microbiol. 36, 630–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dao D. N., Sweeney K., Hsu T., Gurcha S. S., Nascimento I. P., Roshevsky D., Besra G. S., Chan J., Porcelli S. A., Jacobs W. R. (2008) Mycolic acid modification by the mmaA4 gene of M. tuberculosis modulates IL-12 production. PLoS Pathog. 4, e1000081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sambandamurthy V. K., Derrick S. C., Hsu T., Chen B., Larsen M. H., Jalapathy K. V., Chen M., Kim J., Porcelli S. A., Chan J., Morris S. L., Jacobs W. R., Jr. (2006) Mycobacterium tuberculosis ΔRD1 ΔpanCD: a safe and limited replicating mutant strain that protects immunocompetent and immunocompromised mice against experimental tuberculosis. Vaccine 24, 6309–6320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rombouts Y., Burguière A., Maes E., Coddeville B., Elass E., Guérardel Y., Kremer L. (2009) Mycobacterium marinum lipooligosaccharides are unique caryophyllose-containing cell wall glycolipids that inhibit tumor necrosis factor-α secretion in macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 20975–20988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kremer L., Guérardel Y., Gurcha S. S., Locht C., Besra G. S. (2002) Temperature-induced changes in the cell-wall components of Mycobacterium thermoresistibile. Microbiology 148, 3145–3154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zanetta J. P., Timmerman P., Leroy Y. (1999) Determination of constituents of sulphated proteoglycans using a methanolysis procedure and gas chromatography/mass spectrometry of heptafluorobutyrate derivatives. Glycoconj. J. 16, 617–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Burguière A., Hitchen P. G., Dover L. G., Kremer L., Ridell M., Alexander D. C., Liu J., Morris H. R., Minnikin D. E., Dell A., Besra G. S. (2005) LosA, a key glycosyltransferase involved in the biosynthesis of a novel family of glycosylated acyltrehalose lipooligosaccharides from Mycobacterium marinum. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 42124–42133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bruckner J. (1955) Estimation of monosaccharides by the orcinol-sulphuric acid reaction. Biochem. J. 60, 200–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stinear T. P., Seemann T., Harrison P. F., Jenkin G. A., Davies J. K., Johnson P. D., Abdellah Z., Arrowsmith C., Chillingworth T., Churcher C., Clarke K., Cronin A., Davis P., Goodhead I., Holroyd N., Jagels K., Lord A., Moule S., Mungall K., Norbertczak H., Quail M. A., Rabbinowitsch E., Walker D., White B., Whitehead S., Small P. L., Brosch R., Ramakrishnan L., Fischbach M. A., Parkhill J., Cole S. T. (2008) Insights from the complete genome sequence of Mycobacterium marinum on the evolution of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Genome Res. 18, 729–741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fujita Y. (2005) Intact molecular characterization of cord factor (trehalose 6,6′-dimycolate) from nine species of mycobacteria by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Microbiology 151, 3403–3416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bock K., Lundt I., Pedersen C. (1973) Assignment of anomeric structure to carbohydrates through germinal 13C-H coupling constants. Tetrahedron Lett. 14, 1037–1040 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mizutani K., Kasai R., Nakamura M., Tanaka O., Matsuura H. (1983) N.m.r. spectral study of α- and β-l-arabinofuranosides. Carbohydr. Res. 185, 27–38 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Watanabe M., Kudoh S., Yamada Y., Iguchi K., Minnikin D. E. (1992) A new glycolipid from Mycobacterium avium-Mycobacterium intracellulare complex. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1165, 53–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Honda I., Kawajiri K., Watanabe M., Toida I., Kawamata K., Minnikin D. E. (1993) Evaluation of the use of 5-mycoloyl-β-arabinofuranosyl-(1→2)-5-mycoloyl-α-arabinofuranosyl-(1→1′)-glycerol in serodiagnosis of Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex infection. Res. Microbiol. 144, 229–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Watanabe M., Aoyagi Y., Ohta A., Minnikin D. E. (1997) Structures of phenolic glycolipids from Mycobacterium kansasii. Eur. J. Biochem. 248, 93–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Matsunaga I., Naka T., Talekar R. S., McConnell M. J., Katoh K., Nakao H., Otsuka A., Behar S. M., Yano I., Moody D. B., Sugita M. (2008) Mycolyltransferase-mediated glycolipid exchange in mycobacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 28835–28841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dubnau E., Lanéelle M. A., Soares S., Bénichou A., Vaz T., Promé D., Promé J. C., Daffé M., Quémard A. (1997) Mycobacterium bovis BCG genes involved in the biosynthesis of cyclopropyl keto- and hydroxy-mycolic acids. Mol. Microbiol. 23, 313–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Winder F. G., Collins P. B. (1970) Inhibition by isoniazid of synthesis of mycolic acids in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Gen. Microbiol. 63, 41–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Deng L., Mikusová K., Robuck K. G., Scherman M., Brennan P. J., McNeil M. R. (1995) Recognition of multiple effects of ethambutol on metabolism of mycobacterial cell envelope. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39, 694–701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mikusova K., Slayden R. A., Besra G. S., Brennan P. J. (1995) Biogenesis of the mycobacterial cell wall and the site of action of ethambutol. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39, 2484–2489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Minnikin D. E., Kremer L., Dover L. G., Besra G. S. (2002) The methyl-branched fortifications of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Chem. Biol. 9, 545–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Candela T., Maes E., Garénaux E., Rombouts Y., Krzewinski F., Gohar M., Guérardel Y. (2011) Environmental and biofilm-dependent changes in a Bacillus cereus secondary cell wall polysaccharide. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 31250–31262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Skovierová H., Larrouy-Maumus G., Zhang J., Kaur D., Barilone N., Korduláková J., Gilleron M., Guadagnini S., Belanová M., Prevost M. C., Gicquel B., Puzo G., Chatterjee D., Brennan P. J., Nigou J., Jackson M. (2009) AftD, a novel essential arabinofuranosyltransferase from mycobacteria. Glycobiology 19, 1235–1247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Seidel M., Alderwick L. J., Birch H. L., Sahm H., Eggeling L., Besra G. S. (2007) Identification of a novel arabinofuranosyltransferase AftB involved in a terminal step of cell wall arabinan biosynthesis in Corynebacterianeae, such as Corynebacterium glutamicum and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 14729–14740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Birch H. L., Alderwick L. J., Bhatt A., Rittmann D., Krumbach K., Singh A., Bai Y., Lowary T. L., Eggeling L., Besra G. S. (2008) Biosynthesis of mycobacterial arabinogalactan: identification of a novel α(1→3) arabinofuranosyltransferase. Mol. Microbiol. 69, 1191–1206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ojha A. K., Trivelli X., Guerardel Y., Kremer L., Hatfull G. F. (2010) Enzymatic hydrolysis of trehalose dimycolate releases free mycolic acids during mycobacterial growth in biofilms. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 17380–17389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Xin Y., Huang Y., McNeil M. R. (1999) The presence of an endogenous endo-d-arabinase in Mycobacterium smegmatis and characterization of its oligoarabinoside product. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1473, 267–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lee A., Wu S. W., Scherman M. S., Torrelles J. B., Chatterjee D., McNeil M. R., Khoo K. H. (2006) Sequencing of oligoarabinosyl units released from mycobacterial arabinogalactan by endogenous arabinanase: identification of distinctive and novel structural motifs. Biochemistry 45, 15817–15828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sakamoto T., Fujita T., Kawasaki H. (2004) Transglycosylation catalyzed by a Penicillium chrysogenum exo-1,5-α-l-arabinanase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1674, 85–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]