Background: Presenilins (PS) were proposed to form endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ channels, with their function disrupted in familial Alzheimer disease (FAD).

Results: We found no evidence to support this but identified a technical artifact that led to the previous proposal.

Conclusion: PS do not form endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ channels.

Significance: Exaggerated Ca2+ signaling in FAD is not caused by lack of PS Ca2+ channel function.

Keywords: Alzheimer disease, Calcium Intracellular Release, Calcium Signaling, Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER), FAD, Presenilin, Familial, Ion Channel, Leak Channels

Abstract

Familial Alzheimer disease (FAD) is linked to mutations in the presenilin (PS) homologs. FAD mutant PS expression has several cellular consequences, including exaggerated intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) signaling due to enhanced agonist sensitivity and increased magnitude of [Ca2+]i signals. The mechanisms underlying these phenomena remain controversial. It has been proposed that PSs are constitutively active, passive endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+ leak channels and that FAD PS mutations disrupt this function resulting in ER store overfilling that increases the driving force for release upon ER Ca2+ release channel opening. To investigate this hypothesis, we employed multiple Ca2+ imaging protocols and indicators to directly measure ER Ca2+ dynamics in several cell systems. However, we did not observe consistent evidence that PSs act as ER Ca2+ leak channels. Nevertheless, we confirmed observations made using indirect measurements employed in previous reports that proposed this hypothesis. Specifically, cells lacking PS or expressing a FAD-linked PS mutation displayed increased area under the ionomycin-induced [Ca2+]i versus time curve (AI) compared with cells expressing WT PS. However, an ER-targeted Ca2+ indicator revealed that this did not reflect overloaded ER stores. Monensin pretreatment selectively attenuated the AI in cells lacking PS or expressing a FAD PS allele. These findings contradict the hypothesis that PSs form ER Ca2+ leak channels and highlight the need to use ER-targeted Ca2+ indicators when studying ER Ca2+ dynamics.

Introduction

Alzheimer disease (AD)3 is the most common cause of dementia among individuals over 60 years old, affecting ∼2% of people in industrialized countries. Although most AD is idiopathic with late onset (>60 years of age), a small percentage of AD is characterized by early onset and dominant-negative inheritance. Familial AD (FAD) is linked to mutations in three genes encoding the amyloid precursor protein and the two presenilin (PS) homologs. Mutations in PS1 cause the majority of FAD cases.

PSs are nine transmembrane helix proteins (1, 2) that reside in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in their immature holoprotein forms. After assembly of the γ-secretase complex composed of PS, nicastrin, pen-2, and aph-1, PS undergoes endoproteolysis, and the complex is exported from the ER (3). Possible etiological mechanisms for AD pathogenesis have focused on one of its two major histopathological hallmarks, extracellular Aβ plaques, driven by the finding that PS comprises the catalytic core of γ-secretase, the protease responsible for amyloid precursor protein cleavage and Aβ release (4). However, a large body of evidence suggests that PS is involved in intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) homeostasis and that FAD mutations result in [Ca2+]i dysregulation (5–12).

Studies of FAD patient fibroblasts provided the first evidence that [Ca2+]i homeostasis is disrupted in the disease. These experiments demonstrated increased sensitivity and enhanced Ca2+ release in response to InsP3-generating agonists in FAD patients' fibroblasts compared with those from unaffected family members (13–15). These findings have since been extended in numerous in vitro and in vivo studies (16–24). Despite intensive investigation, the mechanisms of mutant PS-enhanced Ca2+ signaling remain controversial (20–31).

[Ca2+]i signaling is a dynamic process involving the plasma membrane (PM), the ER, acidic organelles, and mitochondria. Basal cytoplasmic Ca2+ is maintained at ∼100 nm by multiple mechanisms including plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPases (PMCA), which extrude Ca2+ from the cell, the secretory pathway Ca2+ ATPases that sequester Ca2+ into acidic secretory pathway organelles, and sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA) pumps, which are responsible for Ca2+ uptake into the ER. The ER is the major intracellular Ca2+ store, with basal [Ca2+]ER ∼100–700 μm. Ca2+ is released from the ER through two main ion channels, the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (InsP3R) (by InsP3) and the ryanodine receptor (RyR) (by Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release). A constitutively active, passive ER Ca2+ leak also exists, although its molecular identity is controversial.

It has been proposed that PS holoproteins are Ca2+ channels that comprise the passive ER Ca2+ leak, with FAD PS mutations disrupting this function (26–28, 30, 31). Disruption of this function was suggested to result in Ca2+ overloading of the ER store, with consequent exaggerated Ca2+ release in response to agonists. However, overfilling of ER Ca2+ stores has not been observed in several studies (20, 22, 24, 25, 29). Furthermore, the putative channel function of PS has been reported by only one laboratory (26–28, 30, 31). Accordingly, we here investigated the hypothesis that PS forms Ca2+-permeable leak pathways in the ER. We performed a series of imaging experiments designed to directly measure ER Ca2+ filling rates, basal ER Ca2+ levels, and ER passive Ca2+ leak rates using multiple cell systems, Ca2+ indicators, and imaging protocols. Our results fail to provide consistent evidence in agreement with predictions made by the hypothesis that PS holoproteins function as ER Ca2+ leak channels.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Transgenic Mice

PS1M146V knock-in (KIN) mice were generated and characterized previously (32) and kindly provided by Dr. M. Mattson (NIH). Mice were housed in a pathogen-free, temperature- and humidity-controlled facility, with a 12-h light/dark cycle. Mice were fed a standard laboratory chow diet and double-distilled water ad libitum. All procedures involving mice were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pennsylvania in accordance with NIH Guidelines for the Care and Use of Experimental Animals.

Isolation of Primary Cell Lines

Primary cortical neuron (PCN) cultures were established from single E14–16 mouse embryos following described protocols (33). Cultures were maintained in neurobasal (Invitrogen) medium supplemented with B27 (Invitrogen), l-glutamine (Mediatech), and antibiotics and antimycotics (Invitrogen) at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Half of the medium was replaced every other day. Experiments were performed on 7–8-day-old cultures. Genotyping of embryos was conducted on non-cortical brain tissue obtained from each embryo using described protocols (32). PS conditional double knock-out (PS cDKO) and wild-type (WT) B cells were kindly provided by Dr. D. Allman (University of Pennsylvania) and used within 10 h of isolation.

Mouse Embryonic Fibroblast (MEF) Cell Line Culture

PS double knock-out (PS DKO) MEF cells and retrovirally transfected PS DKO cells were generated previously (34) and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's/F-12 media (Invitrogen) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone) and antibiotics and antimycotics (Invitrogen). Retrovirally transfected MEF cell lines were maintained in 3 μg/ml puromycin (Calbiochem). All cell lines were maintained at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

MEF Cell Line Transfection

MEF cells were transfected with the D1-ER-cameleon plasmid, kindly provided by Dr. R. Tsien (University of California, San Diego, CA) or the D1-Golgi-cameleon plasmid, kindly provided by Dr. T. Pozzan (University of Padua) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's recommended protocol.

Ca2+ Measurements

All imaging was conducted on a Nikon Eclipse microscope using a PerkinElmer Life Sciences Ultraview imaging system.

Permeabilized Cells

MEF cells were incubated with 10 μm Mag-Fura 2-AM (Invitrogen) in Hepes Hanks' balanced salts solution (HHBSS; HBSS supplemented with 10 mm Hepes, 4.2 mm NaHCO3, 1.8 mm CaCl2, pH 7.3, with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA)) at room temperature for 30 min. The same protocol was used to load PCN but at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Cells were washed briefly with cytoplasmic-like media (CLM; 100 mm KCl, 20 mm NaCl, 1 mm EGTA, 0.375 mm CaCl2, 20 mm Pipes, pH 7.3) to remove the loading solution and then permeabilized under microscopic observation for 45 s with 2 μg/ml digitonin. Before recording, cells were perfused at a rate of 1–2 ml/min with CLM for 25 min. Imaging of Mag-Fura 2 was conducted by capturing images at 510 nm every 15 s after excitation at 340 and 380 nm. Microsoft® Excel was used to perform background subtraction for each time point, and Igor Pro was used to fit single exponential functions to the intracellular Ca2+ store filling and release phases and to determine the Δ(340/380) for each cell. Using an iterative nonlinear least square fitting algorithm, the single-exponential equation F(t) = Δ(340/380)[1 − exp(−t/τfill)] + Fo was fitted to the observed data for the filling phase, where Fo is the basal 340/380 ratio, and 1/τfill is the filling rate. The steady-state fill level is F(t→∞). Similarly, the release phase was fitted with a single-exponential equation F(t) = (Fo − Fmin)exp(−t/τrelease) + Fmin, with 1/τrelease being the release rate. Single exponential functions are the simplest model that assumes only time independence of the multiple complex processes involved in ER Ca2+ filling and release, and they provide reasonable fits to the observed data. For example, analyses of Fig. 1 data revealed fitting errors of 8 and 17% for the fill and release phases, respectively, which reflect the 95% confidence interval. It should be noted that this analysis assumes linearity of the relationship between indicator signal and free [Ca2+]ER and does not considered the possible effects of ER Ca2+ buffering on the fluorescence measurements. To confirm indicator saturation does not occur at steady-state Ca2+ fill levels, saturation emission ratios were determined. The average Rmax for Mag-Fura 2 was 0.89, well above the steady-state emission ratios observed in our experiments. In intact cells the basal emission ratio of D1-ER cameleon was 88% of the total ΔR (e.g. the ratio at saturating Ca2+ less the ratio at 0-Ca2+), and the basal emission ratio of D1-Golgi cameleon was 54% of ΔR. Both of these values are within the linear region of the %ΔR versus Ca2+ curve (35). All cells for each experiment were averaged for presentation and data analyses. Imaging of the cameleon Ca2+ indicators was conducted by capturing images at 535 nm (yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)) and 485 nm (cyan fluorescent protein (CFP)) after excitation at 440 nm. Background subtraction and data analysis were conducted as described above. Cyclopiazonic acid (CPA) was purchased from Calbiochem; InsP3 was from Invitrogen.

FIGURE 1.

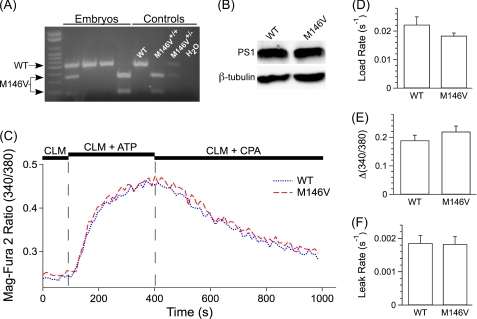

Single cell ER Ca2+ dynamics in WT and PS1M146V+/+ (M146V) primary cortical neurons. A, shown is genotyping of PCN obtained from individual embryos. B, shown is Western blot analysis of PCN lysates using an antibody specific to the PS1 amino terminus. An antibody against β-tubulin was used as loading control. C, shown are representative single cell Mag-Fura 2 signals in permeabilized WT (blue) and M146V (red) PCN during exposure to a CLM. The addition of 1.5 mm MgATP enhanced ER luminal Ca2+, whereas removal of MgATP and the addition of CPA to inhibit SERCA revealed the passive Ca2+ leak. D–F, summaries of single cell intracellular Ca2+ store loading rates after SERCA pump activation (D), steady-state Ca2+ loading (E), and passive Ca2+ leak rates after SERCA pump inhibition (F) are shown. Data are presented as the mean ± S.E. n = 3 embryos of each genotype. n ≥ 25 cells of each genotype. No differences were observed (p > 0.05) by Student's t test.

Intact Cells

Cells were loaded with 2 μm Fura 2 for 30 min in HHBSS with 1% BSA at room temperature. Images were captured every 10 s using the emission/excitation parameters described above for Mag-Fura 2. Background-subtracted 340/380 ratios for each time point were analyzed off-line for individual cells, and were averaged for each experiment for presentation. Igor Pro software was used to determine the [Ca2+]i·s under the ionomycin-induced Ca2+ release versus time curve using the standard equation (36). Ionomycin was purchased from Invitrogen. Experiments using the D1-Golgi-cameleon indicator were conducted as described for D1-ER. Unless otherwise stated, all chemicals were purchased from Sigma and were of the highest purity.

Protein Extraction and Immunoblotting

Cells were sonicated in lysis buffer: 1% Triton X-100, 50 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 250 mm NaCl, and protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science). Homogenates were spun at 14,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was added to 4× loading buffer: 250 mm Tris, pH 6.8, 275 mm sodium dodecyl sulfate, 5.7 mm bromphenol blue, 40% glycerol, 8% β-mercaptoethanol (Bio-Rad), incubated at 95 °C for 2 min, and stored at −20 °C until used. Lysates were run on SDS-PAGE or Tris acetate 3–8% gradient gels (RyR) (NuPAGE), transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (GE Healthcare), blocked with 5% nonfat dried milk, and probed with primary antibody at 4 °C. We used anti-amino-terminal fragment PS1 1:1000 (Millipore), anti-carboxy-terminal fragment PS1 1:500 (Cell Signaling), anti-carboxy-terminal fragment PS2 1:2000 (Calbiochem), anti-InsP3R1 1:1000, kindly provided by Dr. S. Joseph (Thomas Jefferson University), and anti-panRyR 1:2000 (Affinity Bioreagents) and secondary horseradish peroxidase conjugated antibodies: 1:4,000 anti-rat (Chemicon), 1:10,000 anti-mouse (Cell Signaling), 1:10,000 anti-rabbit (GE Healthcare). An Alpha Innotech FluorChem® Q imaging system was used to visualize proteins bands. Bands were quantified with respect to anti-β-tubulin 1:5000 (Invitrogen) or anti-heat shock protein 90 1:1000 (Cell Signaling) using AlphaView® software Version 3.1.1.0.

RNA Extraction, Reverse Transcription, and Real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

RNA was isolated using Qiagen RNeasy mini kit and the manufacturer's recommended protocol. 5 μg of total RNA was used to synthesize cDNA using oligo(dT)12–18 primers (Invitrogen), a Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase kit (Invitrogen), and manufacturer's recommended protocols. A volume of cDNA corresponding to 10 ng of starting RNA was evaluated using a 7300 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems), SYBR green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), 3 μm concentrations of primers, and cycling of 2 min at 50 °C and 10 min at 95 °C followed by 40 cycles at 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min. Primer specificity was validated by the presence of a single PCR product for each primer set after agarose gel analysis. Additionally, a dissociation phase was used at the end of each RT-PCR assay that yielded only a single peak for each primer set. Oligonucleotide primers were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies: InsP3R1 forward (F, 5′-GTATGCGGAGGGATCTACGA-3′; R, 5′-AACACAACGGTCATCAACCA-3′); InsP3R2 (F, 5′-GTCAATGGCTTCATCAGCAC-3′; R, 5′-TGAACTTCTTGGGTGGGTTG-3′); InsP3R3 (F, 5′-GACCGTTGTGTGGTGGAAC-3′; R, 5′-GTTCATGGGGCACACTTTG-3′); RyR1 (F, 5′-CATCTGCTCTGGCTGTGAAG-3′; R, 5′-CAGAAGGGGAGATGGTCAAA-3′); RyR2 (F, 5′-GCGAGGATGAGATCCAGTTC-3′; R, 5′-CTGCTGTTCTTTGTGGATGG-3′); RyR3 (F, 5′-ATGTAGGTCTGCGGGAACAT-3′; R, 5′-ACCTTTGTTTGGAAGCAGGA-3′); PMCA1 (F, 5′-GTGGGCAGGTCATCCAGATA-3′; R, 5′-CCATCAGCTGGAAGAAGGTC-3′); PMCA2 (F, 5′-ATCTCCCTGGGACTGTCCTT-3′; R, 5′-GCTTCACCTTCATCCTCTGC-3′); PMCA3 (F, 5′-GAGGTGGCTGCTATCGTCTC-3′; R, 5′-CACCAGACACATTCCCACAG-3′); PMCA4 (F, 5′-GGGAGATATTGCCCAGATCA-3′; R, 5′-CCTGGATTAGAATTCCATCTGC-3′). The geometric mean of three reference genes (actin) (F, 5′-CCAACCGTGAAAAGATGACC-3′; R, 5′-ACCAGAGGCATACAGGGACA-3′), β2 microglobin (F, 5′-CTGACCGGCCTGTATGCTAT-3′; R, 5′-TATGTTCGGCTTCCCATTCT- 3′), and β-glucuronidase (F, 5′-GGTTTCGAGCAGCAATGGTA-3′; R, 5′-TGCTTCTTGGGTGATGTCATT-3′) was used to control for cDNA. The comparative cycle threshold (ΔΔCt) method was used to analyze amplification data.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using STATA software. Unpaired two-tailed Student's t test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) when more than two independent variables were present was used. Statistical significance was set at a threshold of p < 0.05. All data are reported as the means ± S.E.

RESULTS

Neuronal ER Ca2+ Dynamics Are Not Affected by PS1M146V FAD Mutation

To investigate whether PS forms constitutively active Ca2+ leak channels in the ER and if FAD-linked mutations disrupt such a function, we directly measured ER Ca2+ dynamics in PCN expressing endogenous levels of FAD mutant PS. We employed a PS1M146V-KIN FAD mouse in which the M146V mutation has been targeted to the PS1 locus, resulting in expression of the FAD-linked PS allele at endogenous levels and under proper regulatory controls (32). PCN were isolated from individual embryos generated from PS1M146V+/− crosses to allow for comparisons between littermates (Fig. 1A). In agreement with previous reports (32), WT and PS1M146V+/+ PCN expressed similar levels of PS1 (Fig. 1B). Also, in agreement with previous reports (37), we detected high levels of the mature PS1 amino-terminal fragments but were unable to detect immature holoprotein (data not shown).

If FAD mutations disrupt the ER Ca2+ leak function of PS, we predicted that cells expressing PS1M146V would be able to more quickly fill depleted ER Ca2+ stores, have a higher steady-state ER Ca2+ fill level, and display a decreased rate of passive Ca2+ leak from the ER. To test these predictions, neurons were loaded with the low affinity ratiometric Ca2+ indicator, Mag-Fura 2. The plasma membrane was then permeabilized with a low concentration of digitonin under visual inspection to allow escape of cytoplasmic dye and pharmacological access to intracellular Ca2+ stores while leaving Mag-Fura 2-loaded intracellular compartments intact. PCN were then perfused with a CLM lacking MgATP to allow for digitonin washout and ER Ca2+ depletion. After a base-line recording, the perfusion solution was switched to CLM containing MgATP, which stimulated the SERCA pump to fill the intracellular Ca2+ stores (Fig. 1, C and D). WT and PS1M146V+/+ PCN had similar store filling rates (WT, 0.022 ± 0.0027 s−1; PS1M146V+/+, 0.018 ± 0.00096 s−1; p > 0.1) (Fig. 1D). In addition, the steady-state level of ER filling (the asymptote approached by the single exponential fit of the filling rate) was not different (Δ(340/380): WT, 0.19 ± 0.018; PS1M146V+/+, 0.22 ± 0.020; p > 0.2) (Fig. 1, C and E). Upon filling of the ER Ca2+ stores, the cells were perfused with CLM lacking MgATP and containing the SERCA pump inhibitor CPA. This allowed for direct measurement of the passive leak of Ca2+ from the ER. There were no differences (p > 0.9) between the two groups; WT and PS1M146V+/+ PCN had leak rates of 0.0019 ± 0.00023 s−1 and 0.0018 ± 0.00023 s−1, respectively (Fig. 1, C and F).

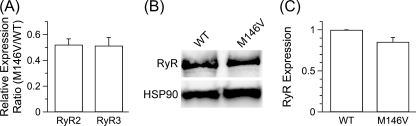

Up-regulation of RyR Ca2+ Release Channels Does Not Compensate for Loss of Putative PS Leak Channels in PS1M146V+/+ Primary Cortical Neurons

It has been suggested that enhanced expression of the RyR Ca2+ release channel may compensate for loss of PS-mediated ER Ca2+ leak in FAD PS-expressing cells (30). To test this possibility, we preformed reverse transcriptase RT-PCR on lysates obtained from PS1M146V+/+ and WT PCN. PCN express RyR isoforms 2 and 3 (Fig. 2A) but not isoform 1 (data not shown). PS1M146V+/+ PCN had ∼50% that of the levels of RyR2 and RyR3 mRNAs compared with WT PCN (n = 2 embryos of each genotype) (Fig. 2A). Western blot analysis of PS1M146V+/+ and WT PCN lysates (n = 4 embryos of each genotype) using an antibody that detects all three murine RyR isoforms indicated a trend (p > 0.05) toward decreased total RyR protein level in PS1M146V+/+ PCN compared with WT PCN (Fig. 2, B and C). Thus, the observed lack of differences in ER Ca2+ store handling between PCN from WT and PS1M146V+/+ cannot be accounted for by up-regulation of RyR expression.

FIGURE 2.

RyR expression in WT and PS1M146V+/+ (M146V) primary cortical neurons. A, shown is RT-PCR analysis of PCN RNA for RyR2 and RyR3 expression using primer sets specific to each. The RyR1 isoform was not detected. The relative expression ratio (M146V/WT) is presented. n = 2 embryos of each genotype. B, shown is a RyR Western blot analysis of lysates obtained from M146V and WT PCN using an antibody that detects all three murine RyR isoforms. Heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) was used as the loading control. C, shown is quantification of total RyR protein expression in WT and M146V PCN. n = 4 embryos of each genotype. A and C, data are presented as the mean ± S.E. No differences were observed (p > 0.05) by Student's t test.

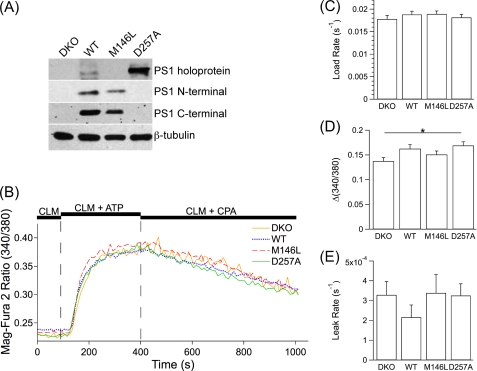

ER Ca2+ Dynamics Are Not Altered in MEF PS DKO Cells Expressing FAD-linked PS1M146L

Our results do not support the hypothesis that FAD mutations in PS disrupt the passive Ca2+ permeability properties of the ER. To extend these studies further, we employed MEFs with both PS alleles genetically ablated (MEF PS DKO) (4) that were retrovirally transduced to constitutively express either recombinant WT human PS1 (hPS1) or PS1 harboring the FAD-linked M146L mutation (hPS1M146L) (34). These cells allow for comparisons between the two PS alleles without confounding effects of endogenous PS expression. PS DKO MEF cells lack PS1 expression, but retroviral transduction with hPS1 or hPS1M146L induced expression and rapid endoproteolysis resulting in low levels of PS1 holoprotein, with the mature amino- and carboxyl-terminal fragments readily detectable (Fig. 3A).

FIGURE 3.

Single cell ER Ca2+ dynamics in permeabilized MEF PS DKO (DKO) cells and MEF PS DKO cells retrovirally transfected to express hPS1 (WT), hPS1M146L (M146L), or hPS1D257A (D257A). A, shown is a Western blot analysis of cell lysates using antibodies specific to PS1 amino and carboxyl termini. The amino terminus antibody also detected the PS1 holoprotein. β-Tubulin was used as a loading control. B, representative single cell Mag-Fura 2 signals in permeabilized MEF DKO (yellow), WT (blue), M146L (red), and D257A (green) cells in response to protocols as described in Fig. 1. C–E, shown are summaries of single cell intracellular Ca2+ store-loading rates after SERCA pump activation (C), steady-state Ca2+ loading (D), and passive Ca2+ leak rates after SERCA pump inhibition (E). Data are presented as the mean ± S.E. n ≥ 3 experiments per cell line. n ≥ 52 cells per cell line. *, p ≤ 0.05 by ANOVA.

The above-described plasma membrane permeabilization protocol was applied to the two cell lines (hPS1 and hPS1M146L) using Mag-Fura 2 as the Ca2+ indicator. The rate of loading of Ca2+ into the ER (0.019 ± 0.00072 s−1 and 0.019 ± 0.00067 s−1; p > 0.9), the steady-state level of store loading (Δ(340/380), 0.16 ± 0.0081; 0.15 ± 0.0071, p > 0.9), and the passive Ca2+ leak rate (0.00022 ± 0.000062 s−1 and 0.00034 ± 0.000094 s−1; p > 0.2) were not different between WT hPS1- and hPS1M146L-expressing MEF cells (Fig. 3, B–E). These findings also fail to support the notion that FAD-linked PS mutations disrupt ER Ca2+ leak pathways.

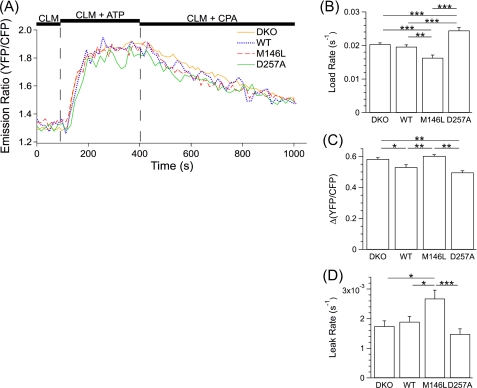

To explore this further, we considered that contributions from non-ER intracellular compartments might have minimized subtle differences between the cell lines. To test this we employed the genetically encoded, ER-targeted D1-ER-cameleon Ca2+ indicator in the above-described permeabilization protocol. This indicator provides sensitive and specific measurements of [Ca2+]ER (38). The hPS1 cells had a faster ER filling rate compared with the hPS1M146L cells (0.020 ± 0.00055 s−1 versus 0.016 ± 0.00083 s−1; p < 0.005) (Fig. 4, A and B), a lower steady-state ER Ca2+ fill level (Δ(YFP/CFP), 0.53 ± 0.016 versus 0.60 ± 0.0088; p < 0.0005)) (Fig. 4, A and C), and a slower ER Ca2+ leak rate (0.0019 ± 0.00018 s−1 versus 0.0027 ± 0.00028 s−1; p < 0.05)) (Fig. 4, A and D). Although the elevated steady-state ER Ca2+ fill level observed in the hPS1M146L cells is consistent with the hypothesis that the PS1M146L allele disrupts an ER Ca2+ permeability, the faster rate of filling and the slower leak rate observed in these cells do not support such a model.

FIGURE 4.

Single MEF cell ER Ca2+ dynamics in permeabilized cells measured with D1-ER-cameleon. [Ca2+]ER was imaged in D1-ER-cameleon-expressing permeabilized MEF PS DKO (DKO) cells and MEF PS DKO cells retrovirally transfected to express hPS1 (WT), hPS1M146L (M146L), or hPS1D257A (D257A). A, shown are representative single cell traces for DKO (yellow), WT (blue), M146L (red), and D257A (green) cells in response to protocols described in Fig. 1. B–D, shown are summaries of single cell ER Ca2+ loading rates after SERCA pump activation (B), steady-state Ca2+ loading (C), and passive Ca2+ leak rates after SERCA pump inhibition (D). Data are presented as the mean ± S.E. n ≥ 3 experiments per cell line. n ≥ 78 cells per cell line. ***, p ≤ 0.0005; **, p ≤ 0.005; *, p ≤ 0.05 by ANOVA.

PS1 Holoprotein Level Does Not Affect ER Ca2+ Dynamics in MEF Cells

Our results indicate that PS1M146V and PS1M146L FAD mutations do not disrupt ER Ca2+ leak permeability in primary cortical neurons and fibroblasts, respectively. However, it has been suggested that the Ca2+ leak channel function of PS resides within the holoprotein (31), whereas we observed that the ER-localized PS holoprotein rapidly undergoes endoproteolysis. We, therefore, performed additional experiments using cells expressing PS1 that accumulates in the ER as a holoprotein. Aspartic acid at position 257 is required for intramolecular cleavage of PS1 into mature fragments. Mutation of this residue causes the accumulation of PS holoprotein in the ER (3, 39) (Fig. 3A). Importantly, this mutation was reported to be without effect on the putative Ca2+ leak channel function of PS1 (31). We, therefore, performed experiments using MEF PS DKO cells and a MEF PS DKO cell line constitutively expressing hPS1 containing a D257A missense mutation (hPS1D257A). Using the above-described permeabilization protocol with Mag-Fura 2 as the Ca2+ indictor, we observed a difference in the steady-state Ca2+ fill level (Δ(340/380), 0.14 ± 0.0072 PS DKO versus 0.17 ± 0.0074 hPS1D257A; p < 0.05) (Fig. 3, B and D) but no differences in the Ca2+ filling rate (0.018 ± 0.00078 s−1 PS DKO versus 0.018 ± 0.00069 s−1 hPS1D257A; p > 0.9) (Fig. 3, B and C) or leak rate (0.00033 ± 0.000068 s−1 PS DKO versus 0.00033 ± 0.000060 s−1 hPS1D257A; p > 0.9) (Fig. 3, B and E) between the two cell lines. None of these results is consistent with the notion that PS holoprotein acts as a passive ER Ca2+ leak channel.

To verify these findings, we performed similar experiments using D1-ER. By comparison with the PS DKO cells, hPS1D257A-expressing cells had a faster ER Ca2+ filling rate (0.024 ± 0.00085 s−1 versus 0.020 ± 0.00038 s−1; p < 0.00005) (Fig. 4, A and B) and a decreased steady-state ER Ca2+ fill level (Δ(YFP/CFP), 0.50 ± 0.011 versus 0.58 ± 0.0094; p < 0.0005) (Fig. 4, A and C); both results are inconsistent with PS acting as an ER Ca2+ leak channel. Furthermore, the two cell lines did not differ in their ER Ca2+ leak rates (0.0015 ± 0.00018 s−1 versus 0.0017 ± 0.00018 s−1; p > 0.8) (Fig. 4, A and D).

In agreement, comparison of PS DKO and hPS1 ER Ca2+ filling rates (Fig. 3, B and C, Fig. 4, A and B), steady-state ER Ca2+ fill levels (Figs. 3, B and D, and 4, A and C), and ER Ca2+ leak rates (Figs. 3, B and E and 4, A and D) identified only a decrease in hPS1 steady-state ER Ca2+ fill level (Δ(YFP/CFP), 0.58 ± 0.0094 PS DKO versus 0.53 ± 0.016 hPS1; p < 0.05) (Fig. 4, A and C) with use of the D1-ER cameleon as the Ca2+ indicator. No other differences in ER Ca2+ dynamics were observed between these two cell lines. Thus, no evidence was found in these cell-based assays for a Ca2+ leak permeability associated with PS1, even in cells that expressed quite high levels of ER-localized PS1 holoprotein.

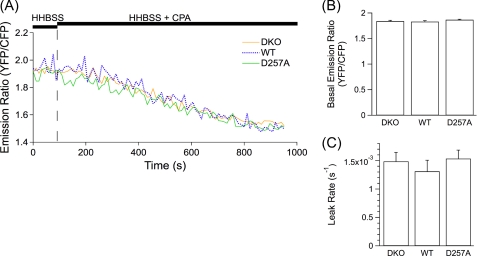

We considered that the permeabilization protocol might result in the loss of a critical cytoplasmic co-factor(s) required for PS Ca2+ leak channel function. To test this possibility, we employed D1-ER to monitor resting [Ca2+]ER and the passive leak of Ca2+ from the ER in intact cells after inhibition of the SERCA pump in PS DKO, hPS1, and hPS1D257A MEF cells. A period of perfusion in Ca2+-containing HHBSS was used to determine the resting (YFP/CFP) ratio of the cameleon indicator in each cell line (Fig. 5A). The basal (YFP/CFP) ratio was not different (p > 0.10 for all comparisons) among the three cell lines (YFP/CFP; PS DKO 1.84 ± 0.017; hPS1, 1.83 ± 0.019; hPS1D257A, 1.87 ± 0.010) (Fig. 5B). Switching the perfusion solution to HHBSS containing CPA resulted in a diminution of [Ca2+]ER due to passive leaks of Ca2+ from the ER. However, no differences were observed (p > 0.9 for all comparisons) in the rates of Ca2+ leak from the ER among PS DKO (0.0015 ± 0.00016 s−1), hPS1 (0.0013 ± 0.00020 s−1), and hPS1D257A (0.0015 ± 0.00015 s−1) cells (Fig. 5, A and C). These results in intact cells are in good agreement with those obtained from permeabilized cells and again indicate that PS is not an ER Ca2+ leak channel.

FIGURE 5.

Single MEF cell ER Ca2+ dynamics in intact cells measured with D1-ER-cameleon. [Ca2+]ER was imaged in D1-ER-cameleon-expressing intact MEF PS DKO (DKO) cells and MEF PS DKO cells retrovirally transfected to express hPS1 (WT) or hPS1D257A (D257A). A, shown are representative single cell traces for DKO (yellow), WT (blue), and D257A (green) cells perfused with HHBSS and then with HHBSS containing CPA to inhibit the SERCA pump. B and C, shown are summaries of single cell [Ca2+]ER measured as the resting YFP/CFP emission ratio (B) and passive Ca2+ leak rates after SERCA pump inhibition (C). Data are presented as the mean ± S.E. n = 3 experiments for each cell line. n ≥ 38 cells for each cell line. No differences were observed (p > 0.05) by ANOVA.

RyR and InsP3R ER Ca2+ Release Channels Do Not Compensate for Loss of Putative PS Ca2+ Leak Channel in MEF PS DKO Cells

As mentioned above, it has been suggested that up-regulation of RyR may compensate for loss of the putative PS-mediated ER Ca2+ leak in cells expressing FAD PS alleles (30). However, we did not detect RyR1–3 protein (Western blot) or mRNA (RT-PCR) in the MEF cells (data not shown). To verify these molecular data, we conducted imaging experiments on permeabilized cells using the Mag-Fura 2 Ca2+ indicator. After Ca2+ store loading, cells were perfused with 2 mm caffeine, a RyR agonist. However, no Ca2+ release was observed (Fig. 6A). These data suggest that up-regulation of RyR is not responsible for any putative Ca2+ leak compensation in PS DKO cells.

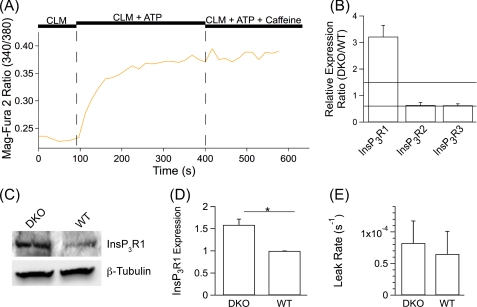

FIGURE 6.

RyR and InsP3R do not compensate for loss of putative Ca2+ channel function of PS1. A, shown is a representative single cell Mag-Fura 2 signal in permeabilized MEF PS DKO cells in response to activation of the SERCA pump by the addition of 1.5 mm MgATP and subsequent responses to addition of 2 mm caffeine. B, shown is the relative mRNA expression ratio of the three InsP3R isoforms (DKO/WT MEF cells) determined by RT-PCR. The area between horizontal lines indicates a less than a 1.5-fold change in expression level. C, shown is Western blot analysis of DKO and WT MEF cell lysates using an InsP3R1-specific antibody and β-tubulin as loading control. D, shown is quantification of InsP3R1 protein expression in DKO and WT MEF cells. E, shown is quantification of ER Ca2+ leak rates in the presence of 100 μg/ml heparin. B, D, and E, data are presented as the mean ± S.E. n ≥ 3 experiments for each cell line. n ≥ 22 cells for each cell line. *, p ≤ 0.05 by Student's t test.

Up-regulation of the expression of InsP3R1 has been reported in MEF PS DKO cells (22). In agreement, RT-PCR experiments revealed an ∼3-fold increase in InsP3R1 mRNA in PS DKO cells compared with hPS1-expressing cells (Fig. 6B). InsP3R2 and InsP3R3 mRNA levels were both slightly diminished (PS DKO/hPS1 ∼0.65) (Fig. 6B). Western blot analysis confirmed that the InsP3R1 protein level was elevated (p < 0.05) in the PS DKO cells by ∼1.6-fold compared with the hPS1 cell line (Fig. 6, C and D). To evaluate the contribution of enhanced InsP3R1 expression in PS DKO cells to the passive ER Ca2+ leak, we repeated the permeabilization experiments in the presence of 100 μg/ml heparin, an inhibitor of InsP3-induced Ca2+ release. Consistent with a previous report (22), there was no difference (p > 0.8) in the ER Ca2+ leak rate between the PS DKO (0.000082 ± 0.000035 s−1) and hPS1 (0.000065 ± 0.000036 s−1) cells in the presence of 100 μg/ml heparin (Fig. 6E). This result suggests that the observed up-regulation of InsP3R1 expression in the PS DKO cells does not compensate for a putative loss of PS-mediated ER Ca2+ leak.

PS Does Not Influence ER Ca2+ Dynamics in Primary B Cells from PS cDKO Mice

To rule out the possibility that use of stable cell lines occluded the observation of a role for the PS holoprotein as an ER Ca2+ leak channel, we repeated experiments using primary B cells obtained from mice in which peripheral B cells lack expression of both PS isoforms (PS cDKO) (Fig. 7). The PS2 locus in these mice was disrupted by deletion of exon 5. Exon 4 of PS1 is flanked by loxP elements, which was deleted in mature B cells using CD19+/Cre mice (40). The Cre-mediated deletion of the floxed alleles is initiated in bone marrow pre-B cells and is completed as B cells first enter peripheral lymphoid tissues. As shown in Fig. 7A, the PS cDKO B cells have no PS2 or PS1 holoprotein expression, whereas B cells obtained from WT littermates express both PS homologs.

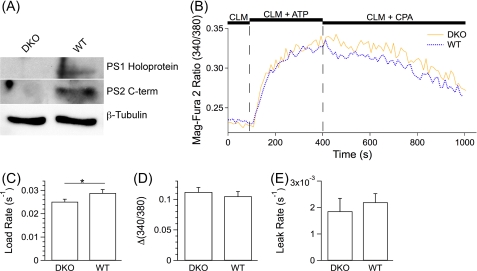

FIGURE 7.

Single cell ER Ca2+ dynamics in permeabilized primary B cells isolated from PS cDKO (DKO) and WT mice. A, shown is expression of PS1 holoprotein and PS2 carboxyl-terminal fragment in WT and DKO B cells. Antibodies specific to PS1 or PS2 were used to detect expression; β-tubulin was used as the loading control. B, shown are representative single permeabilized cell Mag-Fura 2 signals for DKO (yellow) and WT (blue) cells in response to protocols described in Fig. 1. C–E, shown are summaries of single cell ER Ca2+ loading rates after SERCA pump activation (C), steady-state Ca2+ loading (D), and passive Ca2+ leak rates after SERCA pump inhibition (E). C–E, data are presented as the mean ± S.E. n = 4 experiments for each genotype. n ≥ 82 cells for each genotype. *, p ≤ 0.05 by Student's t test.

With Mag-Fura 2 as the ER Ca2+ indicator, WT B cells had a faster (p < 0.05) rate of ER Ca2+ filling compared with PS cDKO B cells (0.025 ± 0.0011 s−1 versus 0.029 ± 00015 s−1) (Fig. 7, B and C). However, no differences in the steady-state fill level (Δ(340/380), 0.11 ± 0.0075 versus 0.10 ± 0.0080; p > 0.5) (Fig. 7, B and D) or the passive Ca2+ release rate (0.0019 ± 0.00049 s−1 versus 0.0022 ± 0.00033 s−1; p > 0.5) (Fig. 7, B and E) were observed. Again, these data fail to provide support for a role for the PS holoprotein as an ER Ca2+ leak channel.

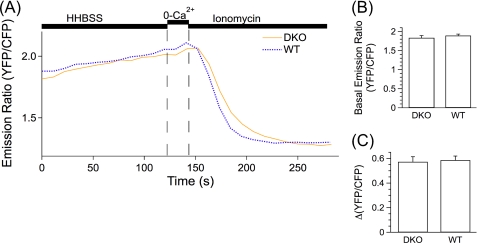

PS Influence Total Cellular, but Not ER, Ionomycin-induced Ca2+ Release in Fibroblasts

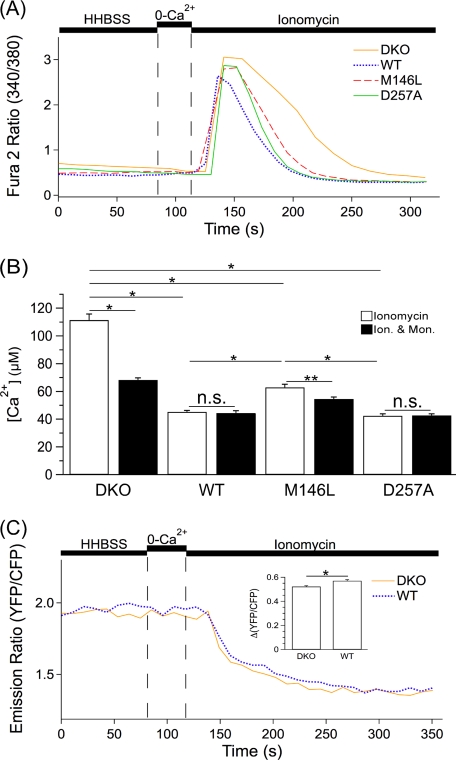

Our results, obtained in several cell systems with two ER Ca2+ indicators, failed to observe a putative Ca2+ leak function associated with expression of PS. How can we account for the different conclusions reached by the other laboratory (26–28, 30, 31)? The previous reports ascribing a Ca2+ channel function to PS largely utilized the increase in [Ca2+]i upon application of the Ca2+ ionophore ionomycin as an indirect measurement of [Ca2+]ER. We, therefore, employed this indirect approach using Fura 2 to measure [Ca2+]i. Using the four MEF cell lines described above, resting [Ca2+]i in HHBSS was recorded before cells were perfused with 5 μm ionomycin in zero-Ca2+ HHBSS. Ionomycin caused a rapid elevation in [Ca2+]i due to release from intracellular stores that subsequently declined to base-line levels. Of note, the elevation of [Ca2+]i was more prolonged in the MEF PS DKO cells and to a lesser extent in the hPS1M146L cells, compared with the hPS1 and hPS1D257A cells (Fig. 8A). The areas under the ionomycin-induced [Ca2+]i versus time curves (AI; the metric used in the previous studies) in PS DKO (111 ± 4.25 μm·s) and PS1M146L (63 ± 2.21 μm·s) were larger (p < 0.0001) than those observed in hPS1 (45.4 ± 1.03 μm·s) and hPS1D257A (42.5 ± 1.34 μm·s) cells (Fig. 8B, open bars). There was no difference in the AI between hPS1 and hPS1D257A cells (p > 0.09). These results recapitulate and are consistent with previous observations that lead to the hypothesis that PS function as ER Ca2+ leak channels, disrupted by FAD-linked mutations (26–28, 30, 31).

FIGURE 8.

Ionomycin-induced Ca2+ release in MEF PS DKO (DKO) cells and MEF PS DKO cells retrovirally transfected to express hPS1 (WT), hPS1M146L (M146L), or hPS1D257A (D257A). A, shown are representative single cell [Ca2+]i responses in Fura 2 loaded DKO (yellow), WT (blue), M146L (red), and D257A (green) MEF cells in response to 5 μm ionomycin in the absence of extracellular Ca2+. B, shown is quantification of the area under the ionomycin (Ion.)-induced [Ca2+]i versus time curve without (open bars) or with (filled bars) pretreatment with 2.5 μg/ml monensin (Mon.) for 2 min (n.s., not significant). C, shown are representative single cell [Ca2+]ER recordings from D1-ER-cameleon expressing DKO (yellow) and WT (blue) MEF cells in response to 5 μm ionomycin in the absence of extracellular Ca2+. The inset shows quantification of the Δ(YFP/CFP) emission ratio. Data are presented as the mean ± S.E. n ≥ 3 experiments for each cell line. n ≥ 76 cells for each cell line. *, p < 0.0001; **, p < 0.005 by ANOVA B or Student's t test C.

How can we reconcile the failure to obtain results consistent with PS as Ca2+ leak channels in the multiple experiments described above with the results obtained using ionomycin? To rule out the possibility that the different AI were a result of different rates of Ca2+clearance across the plasma membrane, we performed RT-PCR for plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase isoforms 1–4. However, no differences in expression of these genes were observed (data not shown). If PS holoproteins are ER Ca2+ leak channels, the prolongation of the ionomycin-induced Ca2+ signal in the PS DKO cells compared with the hPS1 cells should be specific to the ER. To test this, we repeated the ionomycin experiments using D1-ER (Fig. 8C). Contrary to findings using Fura 2, we observed a larger fall of [Ca2+]ER in hPS1 cells compared with PS DKO cells (Δ(YFP/CFP), 0.57 ± 0.0089 versus 0.52 ± 0.0067; p < 0.0001) (Fig. 8C). Using this direct measure of ER Ca2+, these results again do not support the proposition that PS function as ER Ca2+ leak channels. In contrast, these results suggest that PS may influence Ca2+ homeostasis within non-ER intracellular stores.

Several subcellular compartments act as Ca2+ stores, including the Golgi apparatus. To determine whether PS influences resting [Ca2+]Golgi or ionomycin-induced Ca2+ release from the Golgi, we employed D1-Golgi-cameleon (41). Basal Golgi apparatus YFP/CFP ratios were not different (p > 0.1) between the PS DKO (2.45 ± 0.07) and hPS1 (2.61 ± 0.07) cells (Fig. 9, A and B). Switching the perfusion solution to HHBSS with zero Ca2+ and ionomycin also revealed no difference (p > 0.7) in the Δ(YFP/CFP) between the PS DKO (0.57 ± 0.04) and hPS1 (0.59 ± 0.03) cells (Fig. 9C). This suggests that the influence of PS1 on intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis is not a result of changes in [Ca2+]Golgi.

FIGURE 9.

Trans-Golgi Ca2+ in MEF PS DKO (DKO) cells and MEF PS DKO cells retrovirally transfected to express hPS1 (WT). A, shown are representative single cell recordings of D1-Golgi-cameleon in response to 5 μm ionomycin in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ in DKO (yellow) and WT (blue) MEF cells. B and C, summaries of the resting D1-Golgi-cameleon (YFP/CFP) ratio in each cell line (B) and the ionomycin-induced Δ(YFP/CFP) emission ratio of each cell line after ionomycin perfusion (C) are shown. n ≥ 3 experiments for each cell line. n ≥ 25 cells for each cell line. Data are presented as the mean ± S.E.

PS Alleles Influence Kinetics of Ionomycin-induced Ca2+ Release in Fibroblasts

Ionomycin is a H+/Ca2+exchanger with a 1:1 Ca2+ stoichiometry (42). Consequently, it is expected that its rate of Ca2+ release will depend upon the membrane potential and pH (43). We reasoned that the larger AI seen here and previously (26–28, 30, 31) might reflect the influence of PS in the maintenance of intracellular ionic composition. To test this hypothesis, we repeated the ionomycin experiments in the four MEF cell lines after pretreatment with 2.5 μg/ml monensin, a Na+/H+ exchanger, for 2 min to dissipate pH gradients. Monensin pretreatment reduced the AI specifically in PS DKO (68.3 ± 1.55 μm·s; p < 0.0005), and hPS1M146L (54.6 ± 1.42 μm·s; p < 0.005) cells, whereas it was without effect on the AI of hPS1 (44.4 ± 1.75 μm·s; p > 0.6) and hPS1D257A (42.7 ± 1.13 μm·s; p > 0.8) cells (Fig. 8B, filled bars). Notably, this decrease in area was due to a faster return of the (340/380) ratio to base line. This finding suggests that the AI is influenced by factors other than the [Ca2+]ER and is, therefore, not a reliable indicator of the amount of Ca2+ in the ER lumen.

DISCUSSION

Many studies have reported aberrant [Ca2+]i homeostasis associated with expression of FAD-linked PS alleles (5–12). Several mechanisms have been proposed to account for these phenomena (18–22, 24, 31), including the hypothesis that FAD mutations in PS disrupt its normal function as an ER Ca2+ leak channel (26–28, 30, 31). However, our observations here as well as those from other laboratories (22, 25, 29) do not support predictions made by this hypothesis. Another mechanism proposed to explain aberrant [Ca2+]i homeostasis observed in FAD PS cells postulates that FAD PS mutations result in a gain-of-function interaction with the SERCA pump and thereby result in enhanced filling of ER Ca2+ stores (21). Although we did not analyze this hypothesis explicitly in the present study, our results do not provide consistent evidence to support it.

Our experiments employed direct monitoring of ER Ca2+ dynamics in three cell systems including mouse primary cortical neurons, fibroblasts, and primary PS cDKO B cells. We found that cells expressing FAD-linked mutant PS1 and cells devoid of PS expression do not have diminished ER Ca2+ leak rates or consistent differences in ER loading rates or steady-state [Ca2+]ER compared with cells expressing WT PS1. Additionally, no compensatory up-regulation of RyRs (30) was observed that could account for failure to observe phenotypes consistent with the notion that PS function as ER Ca2+ channels. Although we did observe some differences in ER Ca2+ dynamics between cell lines expressing WT hPS1 and those expressing FAD-linked hPS1 alleles, these differences were not consistently observed using different cell lines or experimental paradigms, calling into question their biological significance. We conclude, therefore, that PSs do not function as ER Ca2+ leak channels.

Although we have not specifically investigated the role of PS2 in ER Ca2+ homeostasis in our current study, other studies (29, 44–46) have shown that expression of FAD mutant PS2 alleles does not result in overfilling of ER Ca2+ stores, consistent with our results here with PS1.

Previous reports suggesting that PS holoproteins form ER Ca2+ leak channels used several experimental protocols but nevertheless relied heavily on the ionomycin-induced Ca2+ release protocol. Initial studies employed planar lipid bilayer experiments in which increases in conductance were observed upon incorporation of WT PS1 and PS2 but not upon incorporation of PS harboring FAD mutations (28, 31). However, single channel conductance could not be resolved, requiring noise analysis to estimate unitary currents. Studies to more firmly establish a Ca2+ channel basis for the conductance have not been forthcoming. Another approach used by the authors was to gauge the level of ER filling by monitoring increases in [Ca2+]i after SERCA pump inhibition in intact MEF PS DKO and WT MEF (31). However, this indirect measurement is compromised by strong influences of Ca2+ clearance and buffering. Mag-Fura 2 was measured in permeabilized PS DKO and WT MEF cells (31) and in PS DKO transiently and stably expressing FAD mutants (26, 27) to quantify [Ca2+]ER. However, Mag-Fura 2 may compartmentalize into many distinct intracellular compartments. As shown here, differential results can be obtained depending upon whether Mag-Fura 2 or D1-ER, as a direct indicator of [Ca2+]ER, is used. Subsequent reports employed D1-ER measurements in transfected primary hippocampal neurons from triple transgenic mice (harboring the PS1M146V-KIN mutation), but only a qualitative description was provided without quantitative analyses of leak rates (30). The use of the AI as an indirect estimate of [Ca2+]ER to infer conclusions regarding the role of PS in ER Ca2+ permeability has been the basis of the primary quantitative analysis in the previous studies (26, 28, 30, 31). When we measured the AI, we observed the phenomenon reported in these studies; PS DKO and hPS1M146L expressing fibroblasts had an enhanced area under their whole cell ionomycin-induced Ca2+ release versus time curve compared with WT hPS1- and hPS1D257A-expressing cells. Notably, the increase in AI was mainly due to a slower decay of [Ca2+]i back to basal levels. Importantly, our results obtained using the ER-targeted cameleon Ca2+ indicator found that this increase in AI in PS DKO cells is not due to enhanced filling of the ER.

A question is why the different protocols do not produce the same experimental answer. We observed that pretreatment with the Na+/H+ exchanger monensin before ionomycin application resulted in a specific decrease in the area under the ionomycin-induced Ca2+ release versus time curve in PS DKO and hPS1M146L cells, whereas it was without effect on hPS1 and hPS1D257A cells. The mechanism underlying the attenuation by monensin is not clear. However, it does reveal the pitfall of utilizing the kinetics of ionomycin-induced [Ca2+]i transients to infer the Ca2+ content of specific organelles such as the ER.

In summary, we have shown that PS holoproteins do not form ER Ca2+ leak channels, in contrast to what has been previously proposed (26–28, 30, 31). This conclusion is based on quantitative analyses of ER Ca2+ filling rates, steady-state ER Ca2+ fill levels, and ER Ca2+ leak rates from three different cell systems and using different Ca2+ indicators. Up-regulation of intracellular Ca2+ release channels as compensatory mechanisms cannot account for the failure to provide evidence in support of a function of PS as ER Ca2+ leak channels. We have identified an experimental detail that may account for the discrepancies between these conclusions and those of previous reports. Thus, use of the indirect approach to estimate [Ca2+]ER, integrating the area under the whole cell ionomycin-induced Ca2+ release versus time curve, is influenced by factors other than [Ca2+]ER. Our findings highlight the need to use ER-targeted Ca2+ indicators when using ionomycin to study ER Ca2+ levels. When we performed such an experiment, we found that PS does not confer an ER Ca2+ permeability.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. M. Mattson for providing PS1M146V-KIN mice, Dr. D. Allman for providing WT and PS cDKO B cells, Dr. R. Tsien for providing the ER-targeted cameleon Ca2+ indicator, Dr. T. Pozzan for providing the Golgi apparatus-targeted cameleon Ca2+ indicator, and Dr. S. Joseph for providing the anti-InsP3R1 antibody. We also thank M. Muller, Dr. K. Cheung, and A. Siebert for technical assistance and stimulating discussions.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 MH059937 and R01 GM056328 (to J. K. F.).

- AD

- Alzheimer disease

- FAD

- familial AD

- PS

- presenilin

- PS DKO

- PS double knock-out

- PS cDKO

- PS conditional DKO

- [Ca2+]i

- intracellular Ca2+ concentration

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- AI

- the area under the ionomycin-induced [Ca2+]i versus time curve

- PM

- plasma membrane

- PMCA

- PM Ca2+ ATPase

- SERCA

- sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase

- InsP3R

- inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3) receptor

- RyR

- ryanodine receptor

- KIN

- knock-in

- PCN

- primary cortical neuron(s)

- MEF

- mouse embryonic fibroblast

- HHBSS

- Hepes Hank's balanced salts solution

- CLM

- cytoplasmic-like media

- YFP

- yellow fluorescent protein

- CPF

- cyan fluorescent protein

- CPA

- cyclopiazonic acid

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- hPS1

- recombinant WT human PS1

- hPS1M146L

- recombinant human PS1 containing the M146L mutation

- hPS1D257A

- recombinant human PS1 containing the D257A mutation

- RT-PCR

- real-time PCR.

REFERENCES

- 1. Laudon H., Hansson E. M., Melén K., Bergman A., Farmery M. R., Winblad B., Lendahl U., von Heijne G., Näslund J. (2005) A nine-transmembrane domain topology for presenilin 1. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 35352–35360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Spasic D., Tolia A., Dillen K., Baert V., De Strooper B., Vrijens S., Annaert W. (2006) Presenilin-1 maintains a nine-transmembrane topology throughout the secretory pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 26569–26577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dries D. R., Yu G. (2008) Assembly, maturation, and trafficking of the γ-secretase complex in Alzheimer's disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 5, 132–146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Herreman A., Serneels L., Annaert W., Collen D., Schoonjans L., De Strooper B. (2000) Total inactivation of γ-secretase activity in presenilin-deficient embryonic stem cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 461–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Berridge M. J. (2010) Calcium hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease. Pflugers Arch. 459, 441–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bezprozvanny I., Mattson M. P. (2008) Neuronal calcium mishandling and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Trends Neurosci. 31, 454–463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gandy S., Doeven M. K., Poolman B. (2006) Alzheimer disease. Presenilin springs a leak. Nat. Med. 12, 1121–1123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Marx J. (2007) Alzheimer's disease. Fresh evidence points to an old suspect: calcium. Science 318, 384–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mattson M. P. (2010) ER calcium and Alzheimer's disease. In a state of flux. Sci. Signal. 3, pe10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mattson M. P. (2007) Calcium and neurodegeneration. Aging Cell 6, 337–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stutzmann G. E. (2005) Calcium dysregulation, IP3 signaling, and Alzheimer's disease. Neuroscientist 11, 110–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thinakaran G., Sisodia S. S. (2006) Presenilins and Alzheimer disease. The calcium conspiracy. Nat. Neurosci. 9, 1354–1355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Etcheberrigaray R., Hirashima N., Nee L., Prince J., Govoni S., Racchi M., Tanzi R. E., Alkon D. L. (1998) Calcium responses in fibroblasts from asymptomatic members of Alzheimer's disease families. Neurobiol. Dis. 5, 37–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hirashima N., Etcheberrigaray R., Bergamaschi S., Racchi M., Battaini F., Binetti G., Govoni S., Alkon D. L. (1996) Calcium responses in human fibroblasts. A diagnostic molecular profile for Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging 17, 549–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ito E., Oka K., Etcheberrigaray R., Nelson T. J., McPhie D. L., Tofel-Grehl B., Gibson G. E., Alkon D. L. (1994) Internal Ca2+ mobilization is altered in fibroblasts from patients with Alzheimer disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 534–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chakroborty S., Goussakov I., Miller M. B., Stutzmann G. E. (2009) Deviant ryanodine receptor-mediated calcium release resets synaptic homeostasis in presymptomatic 3xTg-AD mice. J. Neurosci. 29, 9458–9470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stutzmann G. E., Caccamo A., LaFerla F. M., Parker I. (2004) Dysregulated IP3 signaling in cortical neurons of knock-in mice expressing an Alzheimer's-linked mutation in presenilin1 results in exaggerated Ca2+ signals and altered membrane excitability. J. Neurosci. 24, 508–513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stutzmann G. E., Smith I., Caccamo A., Oddo S., Laferla F. M., Parker I. (2006) Enhanced ryanodine receptor recruitment contributes to Ca2+ disruptions in young, adult, and aged Alzheimer's disease mice. J. Neurosci. 26, 5180–5189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stutzmann G. E., Smith I., Caccamo A., Oddo S., Parker I., Laferla F. (2007) Enhanced ryanodine-mediated calcium release in mutant PS1-expressing Alzheimer's mouse models. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1097, 265–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cheung K. H., Shineman D., Müller M., Cárdenas C., Mei L., Yang J., Tomita T., Iwatsubo T., Lee V. M., Foskett J. K. (2008) Mechanism of Ca2+ disruption in Alzheimer's disease by presenilin regulation of InsP3 receptor channel gating. Neuron 58, 871–883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Green K. N., Demuro A., Akbari Y., Hitt B. D., Smith I. F., Parker I., LaFerla F. M. (2008) SERCA pump activity is physiologically regulated by presenilin and regulates amyloid β production. J. Cell Biol. 181, 1107–1116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kasri N. N., Kocks S. L., Verbert L., Hébert S. S., Callewaert G., Parys J. B., Missiaen L., De Smedt H. (2006) Up-regulation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor type 1 is responsible for a decreased endoplasmic-reticulum Ca2+ content in presenilin double knock-out cells. Cell Calcium 40, 41–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Smith I. F., Hitt B., Green K. N., Oddo S., LaFerla F. M. (2005) Enhanced caffeine-induced Ca2+ release in the 3xTg-AD mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurochem. 94, 1711–1718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cheung K. H., Mei L., Mak D. O., Hayashi I., Iwatsubo T., Kang D. E., Foskett J. K. (2010) Gain-of-function enhancement of IP3 receptor modal gating by familial Alzheimer's disease-linked presenilin mutants in human cells and mouse neurons. Sci. Signal. 3, ra22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McCombs J. E., Gibson E. A., Palmer A. E. (2010) Using a genetically targeted sensor to investigate the role of presenilin-1 in ER Ca2+ levels and dynamics. Mol. Biosyst. 6, 1640–1649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nelson O., Supnet C., Liu H., Bezprozvanny I. (2010) Familial Alzheimer's disease mutations in presenilins. Effects on endoplasmic reticulum calcium homeostasis and correlation with clinical phenotypes. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 21, 781–793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nelson O., Supnet C., Tolia A., Horré K., De Strooper B., Bezprozvanny I. (2011) Mutagenesis mapping of the presenilin 1 calcium leak conductance pore. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 22339–22347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nelson O., Tu H., Lei T., Bentahir M., de Strooper B., Bezprozvanny I. (2007) Familial Alzheimer disease-linked mutations specifically disrupt Ca2+ leak function of presenilin 1. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 1230–1239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zatti G., Burgo A., Giacomello M., Barbiero L., Ghidoni R., Sinigaglia G., Florean C., Bagnoli S., Binetti G., Sorbi S., Pizzo P., Fasolato C. (2006) Presenilin mutations linked to familial Alzheimer's disease reduce endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus calcium levels. Cell Calcium 39, 539–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhang H., Sun S., Herreman A., De Strooper B., Bezprozvanny I. (2010) Role of presenilins in neuronal calcium homeostasis. J. Neurosci. 30, 8566–8580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tu H., Nelson O., Bezprozvanny A., Wang Z., Lee S. F., Hao Y. H., Serneels L., De Strooper B., Yu G., Bezprozvanny I. (2006) Presenilins form ER Ca2+ leak channels, a function disrupted by familial Alzheimer's disease-linked mutations. Cell 126, 981–993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Guo Q., Fu W., Sopher B. L., Miller M. W., Ware C. B., Martin G. M., Mattson M. P. (1999) Increased vulnerability of hippocampal neurons to excitotoxic necrosis in presenilin-1 mutant knock-in mice. Nat. Med. 5, 101–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Meberg P. J., Miller M. W. (2003) Culturing hippocampal and cortical neurons. Methods Cell Biol. 71, 111–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Repetto E., Yoon I. S., Zheng H., Kang D. E. (2007) Presenilin 1 regulates epidermal growth factor receptor turnover and signaling in the endosomal-lysosomal pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 31504–31516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Palmer A. E., Jin C., Reed J. C., Tsien R. Y. (2004) Bcl-2-mediated alterations in endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ analyzed with an improved genetically encoded fluorescent sensor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 17404–17409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Grynkiewicz G., Poenie M., Tsien R. Y. (1985) A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J. Biol. Chem. 260, 3440–3450 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Thinakaran G., Borchelt D. R., Lee M. K., Slunt H. H., Spitzer L., Kim G., Ratovitsky T., Davenport F., Nordstedt C., Seeger M., Hardy J., Levey A. I., Gandy S. E., Jenkins N. A., Copeland N. G., Price D. L., Sisodia S. S. (1996) Endoproteolysis of presenilin 1 and accumulation of processed derivatives in vivo. Neuron 17, 181–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Palmer A. E., Tsien R. Y. (2006) Measuring calcium signaling using genetically targetable fluorescent indicators. Nat. Protoc. 1, 1057–1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fassler M., Zocher M., Klare S., de la Fuente A. G., Scheuermann J., Capell A., Haass C., Valkova C., Veerappan A., Schneider D., Kaether C. (2010) Masking of transmembrane-based retention signals controls ER export of γ-secretase. Traffic 11, 250–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rickert R. C., Rajewsky K., Roes J. (1995) Impairment of T-cell-dependent B-cell responses and B-1 cell development in CD19-deficient mice. Nature 376, 352–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lissandron V., Podini P., Pizzo P., Pozzan T. (2010) Unique characteristics of Ca2+ homeostasis of the trans-Golgi compartment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 9198–9203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Liu C., Hermann T. E. (1978) Characterization of ionomycin as a calcium ionophore. J. Biol. Chem. 253, 5892–5894 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fasolato C., Zottini M., Clementi E., Zacchetti D., Meldolesi J., Pozzan T. (1991) Intracellular Ca2+ pools in PC12 cells. Three intracellular pools are distinguished by their turnover and mechanisms of Ca2+ accumulation, storage, and release. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 20159–20167 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Brunello L., Zampese E., Florean C., Pozzan T., Pizzo P., Fasolato C. (2009) Presenilin-2 dampens intracellular Ca2+ stores by increasing Ca2+ leakage and reducing Ca2+ uptake. J. Cell Mol. Med. 13, 3358–3369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Giacomello M., Barbiero L., Zatti G., Squitti R., Binetti G., Pozzan T., Fasolato C., Ghidoni R., Pizzo P. (2005) Reduction of Ca2+ stores and capacitative Ca2+ entry is associated with the familial Alzheimer's disease presenilin-2 T122R mutation and anticipates the onset of dementia. Neurobiol. Dis. 18, 638–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zatti G., Ghidoni R., Barbiero L., Binetti G., Pozzan T., Fasolato C., Pizzo P. (2004) The presenilin 2 M239I mutation associated with familial Alzheimer's disease reduces Ca2+ release from intracellular stores. Neurobiol. Dis. 15, 269–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]