Abstract

Background:

The FAST is a 2 × 2 factorial trial addressing two questions: (1) the role of replacing cisplatin (P) with a non-platinum agent, vinorelbine (N), and (2) the role of adding a third agent, ifosfamide (I), in a doublet based on gemcitabine (G).

Methods:

A total of 433 stage IIIB–IV non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients were randomised to one of four arms: gemcitabine–cisplatin (GP), gemcitabine–vinorelbine, gemcitabine–ifosfamide-cisplatin or gemcitabine–ifosfamide–vinorelbine. Two comparisons were performed: N- vs P-containing regimens and I-triplets vs non-I doublets.

Results:

For N- vs P-containing regimens, adjusted overall survival was 9.7 vs 11.3 months (P=0.044), progression-free survival was 4.9 vs 6.4 months (P=0.020) and response rate was 24% vs 31% (P=0.124), respectively. No statistically significant difference was observed between doublets and triplets. Grade 3–4 haematological toxicity was significantly more frequent in P-containing therapy; grade 3–4 leucopenia was significantly more common in triplets. Concerning non-haematological toxicity, grade 3–4 nausea-vomiting was significantly increased in P-containing regimens.

Conclusions:

This trial provides evidence of a slight survival superiority of GP-containing regimens over platinum-free N-containing chemotherapy. This trial also confirms that the addition of a third chemotherapy agent (I) to a standard G-based doublet does not improve treatment outcome.

Keywords: doublet, chemotherapy, cisplatin, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), triplet

Until recently, the standard treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has been based on a combination of cisplatin with a third-generation chemotherapic agent, such as paclitaxel, docetaxel, vinorelbine or gemcitabine (Azzoli et al, 2009; D’Addario et al, 2010). These regimens obtained comparable outcome results (Kelly et al, 2001; Scagliotti et al, 2002; Schiller et al, 2002) but, among these, at least in Europe, cisplatin–gemcitabine has been the most used combination (Le Chevalier et al, 2005).

At the time this trial was designed the discussion concerning optimal chemotherapy treatment of advanced NSCLC was mainly focused on the uncertain superiority of platinum- vs non-platinum-based regimens and of triplets vs doublets.

Despite its pivotal role in NSCLC management, cisplatin is associated with a number of serious side effects including nausea-vomiting, neurotoxicity and renal function impairment and it is burdened by delivery problems such as the need for prolonged hydration (Tiseo et al, 2007). To overcome these limitations, most clinicians were considering the use of carboplatin and of platinum-free combinations as a possible alternative.

Although carboplatin and cisplatin have similar mechanism of action and spectrum of activity, some trials and an individual patient data meta-analysis evidenced that cisplatin-based is slightly superior to carboplatin-based chemotherapy in terms of response rate (RR) and also, in certain subgroups (third-generation regimens and non-squamous histology), in terms of survival, without a significant increase in severe toxicity (Ardizzoni et al, 2007).

The activity and tolerability of third-generation agents led many investigators to evaluate platinum-free doublets in the hope that platinum analogues could be spared for the treatment of advanced NSCLC (Georgoulias et al, 2001; Kosmidis et al, 2002; Gridelli et al, 2003).

Addition of a third agent to platinum-based doublet may be an option to improve outcomes in NSCLC. This strategy has been shown to be associated with superior outcomes in other malignancies (Vermorken et al, 2007). This led to the conduct of multiple trials comparing a two-drug regimen with a three-drug regimen in advanced NSCLC patients (Comella et al, 2000; Alberola et al, 2003; Laack et al, 2004; Paccagnella et al, 2006). Our group, in particular, developed two different triplets including ifosfamide, an alkylating agent with activity against NSCLC commonly used in old regimens. Gemcitabine, ifosfamide and cisplatin (GIP) and gemcitabine, ifosfamide and vinorelbine (GIN) evidenced very interesting results in phase II first-line studies, with a RRs of 54% and 52% and a median overall survival (OS) of 12 and 11 months, respectively, with acceptable toxicity profiles (Boni et al, 2000; Baldini et al, 2001). The results of these studies suggested further investigations within prospective randomised study assessing the role of these triplets, with or without platinum.

Considering this background, a randomised 2 × 2 factorial phase III trial addressing two questions: (1) the role of replacing cisplatin (P) with a non-platinum agent, vinorelbine (N), and (2) the role of adding a third agent, ifosfamide (I), in a chemotherapy doublet based on gemcitabine (G) was performed. Here, the results of this multicenter Italian trial are reported.

Patients and methods

Study population

Patients with histologically or cytologically confirmed locally advanced stage IIIB (supra-clavicular node and/or malignant plural effusion) or metastatic stage IV (according sixth TNM classification) NSCLC were eligible for the study. Patients were required to be chemotherapy-naive for advanced disease. Eligibility criteria included: age ⩾18 years, ECOG performance status (PS) ⩽2, adequate haematological, hepatic and renal function. Patients with active infection, severe co-morbidity and a history of previous or concomitant neoplasm, other than epithelial tumours of the skin or in situ carcinoma of the uterine cervix, were ineligible.

The protocol was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. The study was approved by the ethics committee of each participating institution and written informed consent was obtained from each patient before inclusion.

Study design and treatment plan

This was a randomised factorial study with the following two primary aims: (1) to compare the effectiveness of two different treatment strategies, one containing cisplatin and one containing vinorelbine instead of cisplatin; (2) to compare the effectiveness of two different treatment strategies, one with two and one with three drugs for the addition of ifosfamide, both in terms of OS.

The factorial design was chosen to improve study efficiency, assuming no interaction between the two factors under investigation.

After stratification by centre, eligible patients were randomly assigned to one of four treatment arms in a 1 : 1 : 1 : 1 ratio: gemcitabine–cisplatin (GP), gemcitabine–vinorelbine (GN), GIP and GIN. Random assignment was centrally performed by fax at the Trial Unit of the National Institute for Cancer Research of Genova with the use of permuted blocks of variable size.

The GP regimen consisted of: gemcitabine 1250 mg m–2 on days 1 and 8 and cisplatin 80 mg m–2 (infused with hydration) on day 1 every 21 days. The GN regimen consisted of: gemcitabine 1250 mg m–2 on days 1 and 8 and vinorelbine 25 mg m–2 on days 1 and 8 every 21 days. The GIP regimen consisted of: gemcitabine 1000 mg m–2 on days 1 and 8, ifosfamide 2 g m–2 (with mesna total dose of 1200 mg administered as an i.v. bolus immediately before ifosfamide infusion and after 4 and 8 h) on day 1 and cisplatin 80 mg m–2 (infused with hydration) on day 1 every 21 days. The GIN regimen consisted of: gemcitabine 1000 mg m–2 on days 1 and 8, ifosfamide 3 g m–2 (with mesna total dose of 1600 mg administered as an i.v. bolus immediately before ifosfamide infusion and after 4 and 8 h) on day 1 and vinorelbine 25 mg m–2 on days 1 and 8 every 21 days.

Clinical examination was performed before every cycle and 21 days from the end of therapy. Complete blood cell count was performed on day 1 and between days 12 and 14.

Serum liver and renal functions were measured before each cycle of chemotherapy and at the end of the treatment. Dose reductions of single drugs and delay of each cycle were applied according to standard criteria defined by protocol schedules. Primary prophylaxis with G-CSF was not allowed. The treatment was given for a maximum of six cycles unless there were disease progression, unacceptable toxicity or withdrawal of the consent.

Statistical analyses

The primary end point was OS. Secondary end points included characterisation of toxicities, objective RR and progression-free survival (PFS). The study was designed to detect a 25% relative reduction of the mortality hazard, in both planned comparisons (N-based vs P-based regimens and three-drug vs two-drug regimens). We aimed to enrol enough patients to yield the occurrence of 385 deaths, which would give a statistical power of 80% to reject the null hypothesis of no significant difference in the OS time in the two planned comparisons, assuming a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.75, a significance level of a two-sided log-rank test fixed at 5%, an accrual rate equal to 230 patients per year and a minimum follow-up duration of 2 years. No adjustment for multiple comparisons was made.

Overall survival was measured from the date of randomisation to the date of death from any cause. Progression-free survival was measured from the date of randomisation to the first date of disease progression or of death from any cause. In both OS and PFS analyses, observation times were censored at the limit date of 30 September 2009 for patients in whom no event occurred.

Objective response (complete and partial response) was evaluated according to RECIST criteria (version 1.0) (Therasse et al, 2000). Response was assessed after three and six courses with a CT scan. The best overall response is the best response recorded from the start of treatment until disease progression. Patients who received at least one dose of chemotherapy were considered evaluable for response; any patient who died early, had early suspension of chemotherapy because of any cause or was not evaluated after randomisation was considered non-responder.

Toxicity grading, based on NCIC–CTC toxicity criteria (version 2.0, National Cancer Institute of Canada Common Toxicity Criteria, Kingston, ON, Canada), was evaluated weekly. All efficacy analyses were based on the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle. Safety was analysed on all subjects receiving at least one dose of study drugs, according to treatment actually received (safety population).

Median period of follow-up was calculated for the entire study cohort according to the reverse Kaplan–Meier method. Non-parametric estimates of the survivor functions and hazard ratios were based on the Cox proportional hazards model, using the average covariate method, and each of them was adjusted by the other treatment factor (presence of platinum and number of drugs). Confidence intervals (CIs) of median survival times were calculated according to the log–log method of Brookmeyer and Crowley (1982). Adjusted estimates of objective RRs and ORs with their 95% CIs were obtained by a logistic regression model. Wald χ2-test was used to test the statistical significance of all coefficients. All reported P-values are two-sided and significant level was set at ≤0.05. Efficacy analyses were performed whenever the results did not suggest the presence any interaction between the two different treatment modalities. Statistical analyses were performed by LB at Istituto Toscano Tumori using SAS System 9.2 (Cary, NC, USA) and R statistical packages.

Results

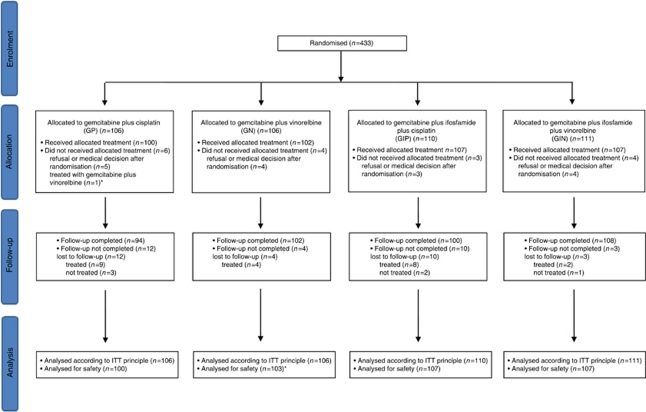

Figure 1 summarises patient disposition in the trial. From October 2001 to July 2006, a total of 433 stage IIIB–IV NSCLC patients were enrolled and randomly assigned to one of the four treatment regimens: GP (n=106), GN (n=106), GIP (n=110) and GIN (n=111), at 15 participating Italian centres. Therefore, 216 patients were expected to receive P-based therapy (GP and GIP) and 217 N-based regimen (GN and GIN), whereas 212 patients were expected to be treated with a doublets (GP and GN) and 221 with a triplets (GIP and GIN). Of these 433 patients, 16 (3.7%) did not receive any study therapy; thus, 417 patients are included in the safety analysis population. Six (1.4%) out of 433 patients with non-measurable disease at randomisation were excluded from the analysis of best overall response.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram of the study. A total of 417 patients (96.3%) received study treatment consisting of at least one dose of chemotherapy. *One patient was assigned to the GP arm but received GN treatment. This patient was included in the GN arm for the safety analysis. GP, gemcitabine–cisplatin; GN, gemcitabine–vinorelbine; GIP, gemcitabine–ifosfamide–cisplatin; GIN gemcitabine–ifosfamide–vinorelbine.

Patient characteristics

As shown in Table 1, patient characteristics for ITT population at baseline were well balanced between the two groups in both comparisons. The median age of patients was 63 years (range of 29–79). Most patients in all arms were male and had an ECOG PS of 0. In all, 80% of patients in all treatment groups had stage IV or recurrent disease and 27% had squamous histology. Supplementary Table S1 reported baseline patient and tumour characteristics by allocated treatment arm.

Table 1. Baseline patient and tumour characteristics by trial interventions.

|

Platinum-based regimen

|

Number of drugs

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Yes (N=216)

|

No (N=217)

|

2-Drugs (N=212)

|

3-Drugs (N=221)

|

|||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Median age (range), years | 63 (29–79) | 64 (35–77) | 62.5 (29–77) | 64 (41–79) | ||||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 170 | 79 | 176 | 81 | 170 | 80 | 176 | 80 |

| Female | 46 | 21 | 41 | 19 | 42 | 20 | 45 | 20 |

| ECOG PS | ||||||||

| 0 | 132 | 61 | 132 | 61 | 128 | 60 | 136 | 62 |

| 1 | 74 | 34 | 77 | 35 | 75 | 35 | 76 | 34 |

| 2 | 10 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 9 | 4 | 9 | 4 |

| Stage | ||||||||

| IIIB | 46 | 21 | 42 | 19 | 45 | 21 | 43 | 19 |

| IV | 170 | 79 | 175 | 81 | 167 | 79 | 178 | 81 |

| Method of diagnosis | ||||||||

| Histology | 145 | 67 | 144 | 66 | 137 | 65 | 152 | 69 |

| Cytology | 62 | 29 | 63 | 29 | 65 | 31 | 60 | 27 |

| Missing value | 9 | 4 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 4 | 9 | 4 |

| Histology | ||||||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 90 | 42 | 92 | 42 | 90 | 42 | 92 | 42 |

| Squamous | 59 | 27 | 60 | 28 | 55 | 26 | 64 | 29 |

| Large cell | 6 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| NOS | 61 | 28 | 63 | 29 | 63 | 30 | 61 | 27 |

Abbreviations: ECOG=Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; NOS=not otherwise specified; PS=performance status.

Therapy administration and toxicity

The mean and median number of treatment cycles administered were 4.45 and 5 (range 1–6), respectively, in patients treated with GP and GIP and 4.19 and 4 (range 1–6), respectively, for those who received GN and GIN. In the second comparison, the mean and median were 4.37 and 5 (range 1–6), respectively, for patients treated with doublets and 4.27 and 4.5 (range 1–6), respectively, for patients treated with triplets.

Grade 3 and 4 haematologic and non-haematologic toxicities exceeding 5% of the treated patients are reported in Table 2. Haematological toxicity consisted mainly in grade 3–4 anaemia (14% vs 5% P=0.001), leucopenia (33% vs 23% P=0.025) and thrombocytopenia (32% vs 4% P<0.001), significantly more frequent in P-containing vs N-containing regimens. Also febrile neutropenia was significantly more frequent in patients treated with P-containing vs N-containing regimens (3% vs 0.5% P=0.044). The triplets were more frequently responsible of grade 3–4 leucopenia (35% vs 22% P=0.003) than doublets.

Table 2. NCIC/CTC version 2.0 grade 3 and 4 toxicities exceeding 5% of patients in the treated patients.

|

Platinum-based regimen

|

Number of drugs

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Yes (N=207)

|

No (N=210)

|

2-Drugs (N=203)

|

3-Drugs (N=214)

|

|||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | P-value | No. | % | No. | % | P-value | |

| Anaemia | 30 | 14 | 10 | 5 | 0.001 | 16 | 8 | 24 | 11 | 0.254 |

| Leucopenia | 69 | 33 | 49 | 23 | 0.025 | 44 | 22 | 74 | 35 | 0.003 |

| Neutropenia | 92 | 44 | 77 | 37 | 0.095 | 74 | 36 | 95 | 44 | 0.091 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 67 | 32 | 8 | 4 | <0.001 | 33 | 16 | 42 | 20 | 0.339 |

| Nausea and vomiting | 24 | 12 | 8 | 4 | 0.004 | 16 | 8 | 16 | 7 | 0.890 |

| Fatigue | 27 | 13 | 16 | 8 | 0.074 | 19 | 9 | 24 | 11 | 0.507 |

Concerning non-haematological toxicity, grade 3–4 nausea-vomiting (12% vs 4% P=0.004) was significantly increased in P-containing regimens compared with N-therapy; no other statistically significant differences in toxicity were observed in both comparisons (Table 2).

Supplementary Table S2 reported grade 3 and 4 haematologic and non-haematologic toxicities exceeding 5% of the treated patients by allocated treatment arm.

Efficacy

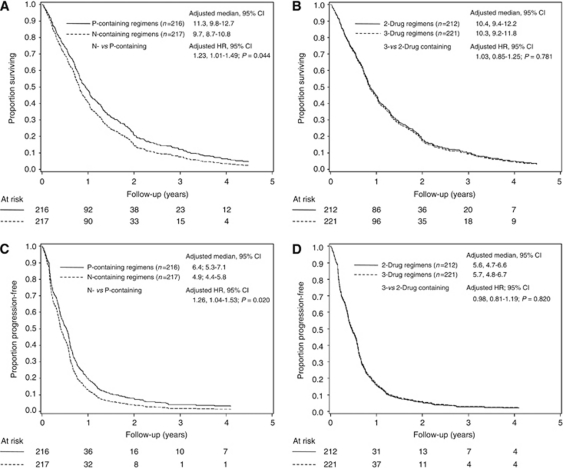

Primary efficacy outcomes by two comparisons are summarised in Table 3. Supplementary Table S3 reported response and survival outcomes by allocated treatment arm. Median follow-up was 66.4 months (interquartile range: 49.7–67.5). A total of 29 patients (6.7%) were lost to follow-up. Curves for OS and PFS are summarised in Figure 2 for the two comparisons.

Table 3. Response and survival outcomes by trial interventions.

|

Platinum-based regimen

|

Number of drugs

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Yes (N=216)

|

No (N=217)

|

2-Drugs (N=212)

|

3-Drugs (N=221)

|

|||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Best overall response a | ||||||||

| CR | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| PR | 62 | 29 | 48 | 22 | 57 | 27 | 53 | 26 |

| SD | 77 | 36 | 71 | 33 | 69 | 33 | 79 | 35 |

| PD | 29 | 14 | 39 | 18 | 34 | 16 | 34 | 16 |

| NE | 41 | 19 | 52 | 24 | 47 | 22 | 46 | 22 |

| Adjusted percentage of CR+PR (95% CI) | 31% (25–37%) | 24% (19–30%) | 29% (23–35%) | 26% (21–33%) | ||||

| Adjusted OR (95% CI), P-value | 0.72 (0.47–1.10), P=0.124 | 0.86 (0.56–1.32), P=0.487 | ||||||

| PFS | ||||||||

| Number of events | 201 | 213 | 201 | 213 | ||||

| 1-Year and 2-year adjusted probability | 19.7% and 7.6% | 12.9% and 3.9% | 15.8% and 5.3% | 16.5% and 5.7% | ||||

| Adjusted median (95% CI), months | 6.4 (5.3–7.1) | 4.9 (4.4–5.8) | 5.6 (4.7–6.6) | 5.7 (4.8–6.7) | ||||

| Adjusted HR (95% CI), P-value | 1.26 (1.04–1.53), P=0.020 | 0.98 (0.81–1.19), P=0.820 | ||||||

| OS | ||||||||

| Number of events | 190 | 209 | 195 | 204 | ||||

| 1-Year and 2-year adjusted probability | 47.9% and 20.7% | 40.6% and 14.5% | 44.8% and 17.9% | 43.8% and 17.0% | ||||

| Adjusted median (95% CI), months | 11.3 (9.8–12.7) | 9.7 (8.7–10.8) | 10.4 (9.4–12.2) | 10.3 (9.2–11.8) | ||||

| Adjusted HR (95% CI), P-value | 1.23 (1.01–1.49), P=0.044 | 1.03 (0.85–1.25), P=0.781 | ||||||

Abbreviations: CI=confidence interval; CR=complete response; HR=hazard ratio; NE=not evaluated; OR=odds ratio; OS=overall survival; PD=progressive disease; PFS=progression-free survival; PR=partial response; SD=stable disease.

Six patients without measurable disease at randomisation were excluded from the analysis of best overall response.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) curves for two comparisons. (A, C) N-containing versus P-containing regimens; (B, D) 3- versus 2-drug regimens. N, vinorelbine; P, cisplatin.

Median OS was 10.3 months for all 433 patients. Adjusted median survival was 11.3 months (95% CI: 9.8–12.7) vs 9.7 months (95% CI: 8.7–10.8) favouring P-containing therapies (HR)=1.23; 95% CI: 1.01–1.49; P=0.044) (Figure 2A). Adjusted median survival was 10.4 months (95% CI: 9.4–12.2) and 10.3 months (95% CI: 9.2–11.8) for doublets and triplets, respectively (HR = 1.03; 95% CI: 0.85–1.25; P=0.781) (Figure 2B). There was no statistically significant interaction between the trial arms (P=0.146).

Adjusted median PFS was 6.4 months for P-containing regimens (95% CI: 5.3–7.1) and 4.9 months for N-containing therapies (95% CI: 4.4–5.8; HR=1.26; 95% CI: 1.04–1.53; P=0.020) (Figure 2C). Adjusted median PFS was 5.6 months for doublets (95% CI: 4.7–6.6) and 5.7 months for triplets (95% CI: 4.8–6.7; HR=0.98; 95% CI: 0.81–1.19; P=0.820) (Figure 2D). No evidence of multiplicative interaction between treatment arms was observed (P=0.073).

Adjusted overall RR (complete and partial responses) were 31% vs 24% for platinum vs non-platinum therapies, respectively (OR=0.72; 95% CI: 0.47–1.10; P=0.124), and 29% vs 26% for doublets and triplets, respectively (OR=0.86; 95% CI: 0.56–1.32; P=0.487) (test for interaction between trial arms: P=0.748).

Additional analyses

Clinical results were retrospectively analysed by patient histology (squamous vs non-squamous tumours). The RR in non-squamous patients was numerically greater than that achieved in squamous (30% vs 23% P=0.151). Median survival was 10.8 months (95% CI: 9.7–12.4) and 9.4 months (95% CI: 8.4–10.4) for non-squamous and squamous patients, respectively (HR=1.25; 95% CI: 1.00–1.56; P=0.048). Median PFS was 5.8 months (95% CI: 4.9–6.7) and 4.9 months (95% CI: 4.3–6.0) for non-squamous and squamous patients, respectively (HR=1.18; 95% CI: 0.95–1.46; P=0.136).

No evidence of interaction effect between histological subtype and treatment type (P- vs N-containing regimens) was observed on RR, PFS and OS (P=0.943, 0.923 and 0.542, respectively).

Discussion

This prospective, factorial randomised trial is the only single study in advanced NSCLC treatment demonstrating a statistically significant slight superiority in survival of platinum-containing regimens over platinum-free chemotherapy. On the contrary, this trial does not provide evidence of an improved outcome with the addition of a third chemotherapy agent, such as ifosfamide, to a standard doublet.

At the time this trial was designed, the controversy about standard chemotherapy treatment of advanced NSCLC was mainly concentrated on the role of platinum and on the optimal number of agents to be used. Therefore, we designed this study aimed at answering with a single study these two relevant questions. Considering, cisplatin–gemcitabine as one of the most widely used platinum-based doublets for the treatment of advanced NSCLC in EU, the available data about GN combination (Gridelli et al, 2000) and the previous experience of our group with two different triplets (GIP and GIN) (Boni et al, 2000; Baldini et al, 2001), we included these four treatment arms in a 2 × 2 factorial study design.

Results from this trial are largely consistent with the data, which have been subsequently available in the literature about the first-line treatment of NSCLC patients and, also, with International guidelines (Azzoli et al, 2009; D’Addario et al, 2010).

No previous study was successful in demonstrating a statistically significant survival advantage in favour of platinum-based regimens, compared with platinum-free combinations. However, in some studies, a trend towards a higher RR or PFS or OS was observed in patients treated with platinum-based combinations compared with those treated with cisplatinum-free regimens (Georgoulias et al, 2001, 2004; Kosmidis et al, 2002; Alberola et al, 2003; Gridelli et al, 2003; Smit et al, 2003; Kubota et al, 2008). D’Addario et al (2005) reported the results of a meta-analysis based on abstracted data from randomised phase II and III studies designed to compare the efficacy and toxicity of platinum-based to non-platinum-based chemotherapy in advanced NSCLC. As in our trial, the platinum-based combinations had a significantly higher 1-year survival rate compared with the non-platinum regimens.

The results of our study concerning this comparison are consistent also with the results of two other meta-analysis of phase III trials comparing third-generation platinum- vs non-platinum-based combinations (Pujol et al, 2006; Rajeswaran et al, 2008). Pujol et al (2006) showed that patients treated with platinum-based doublets had a statistically significant reduction in the risk of death (OR=0.88, P=0.044) without an unacceptable increase in toxicity. Moreover, Rajeswaran et al (2008) confirmed that cisplatin-, but not carboplatin-based regimens, are associated with a slight survival advantage at 1-year compared with non-platinum-based doublets.

In our study, the absolute benefit at 1-year turns out to be relatively small, but it becomes more relevant later, as shown in the Kaplan–Meier curve, with a higher percentage of long-term surviving patients in the P-containing arms. This result is reinforced by the high median follow-up time (66.4 months) of our study. This is in keeping with the hypothesis that the added benefit of platinum, albeit quantitatively small, may translate into a long-term higher survival probability.

P-containing regimens showed, moreover, a short-term benefit in PFS, about 2 months in median PFS and 6.8% absolute improvement in 1-year PFS probability, without any statistically significant difference in RR. This observation might be probably related to the high percentage (22%) of patients not evaluable for response and to the lack of uniform external and blinded radiological response assessment.

One of the most remarkable results of the study was the fairly good tolerability of all the four regimens, with a slightly higher haematological toxicity in P-containing regimens, which were penalised also by a higher incidence of nausea-vomiting.

Also the triplets were well tolerated, even if with significantly more grade 3–4 leucopenia compared with doublets. According to previous results, also in our trial the addition of a third agent to doublet therapy showed no survival benefit (Delbaldo et al, 2004). In interpreting these results, however, it has to be reminded that doses of both gemcitabine and ifosfamide were different in the three-drug regimens under testing in accordance to previous phase II experience. In addition, the RR observed in this trial observed with triplets was lower than that reported in phase II studies probably as consequence of less stringent eligibility criteria and radiological response assessment.

Overall, the outcome data obtained in the FAST trial population were good; in particular, a median survival of 10.3 months was observed in the overall population, which compares favourably with that of the more relevant randomised phase III trials performed with different platinum doublets, where the median OS ranged between 7.4 and 9.9 months (Kelly et al, 2001; Scagliotti et al, 2002; Schiller et al, 2002). Moreover, all outcome measures were similar in squamous and non-squamous histology subtypes, suggesting the lack of treatment–histology interactions with the chemotherapy regimens used in this study.

With the limitations of long study duration, this trial confirms that in advanced NSCLC patients with a PS of 0 or 1, a two-drug platinum-based combination, such as cisplatin–gemcitabine, should be preferred as first-line treatment. The results of this trial along with those of platinum vs non-platinum meta-analysis and of carboplatin vs cisplatinum meta-analysis, suggest that cisplatin should remain a fundamental ingredient of first-line chemotherapy of advanced NSCLC patients, especially when a long-term survival can be anticipated, such as in fit patients with oligometastatic disease. Non-platinum combinations, however, can remain a reasonable option in patients who have contraindications to platinum therapy or those who are unfit or have very advanced bulky and multimetastic disease.

On the contrary, our study, in keeping with the results of a meta-analysis, further supports the concept that, at the moment, there is no place for increasing the number of chemotherapy agents beyond two in first-line regimens in the treatment of advanced NSCLC. Perhaps, the use of triplets might deserve further investigation in locally advanced non-metastatic disease where the increased RR associated with this strategy, as seen in some other studies, might lead to an improvement of tumour down-staging and, ultimately, to a better local control with subsequent locoregional therapies.

Although the currently most employed drug combinations for first-line treatment of advanced NSCLC, such as cisplatinum–pemetrexed and carboplatin-paclitaxel-bevacizumab (Sandler et al, 2006; Scagliotti et al, 2008), were not included in this study, we believe that our results can contribute further to the clarification of the optimal chemotherapy management of advanced NSCLC.

Acknowledgments

We thank all of the patients, families and institutions involved in this study. We thank Caterina Donato (Oncology Unit A, National Institute for Cancer Research, Genova) and Roberta Camisa (Oncology Unit, University Hospital, Parma) for data management. We also remember our very good friend and colleague Dr L Manzione (Oncology Unit, S Carlo Hospital, Potenza, Italy) who gave an important contribution to this study.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on British Journal of Cancer website (http://www.nature.com/bjc)

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Material

References

- Alberola V, Camps C, Provencio M, Isla D, Rosell R, Vadell C, Bover I, Ruiz-Casado A, Azagra P, Jiménez U, González-Larriba JL, Diz P, Cardenal F, Artal A, Carrato A, Morales S, Sanchez JJ, de las Peñas R, Felip E, López-Vivanco G, Spanish Lung Cancer Group (2003) Cisplatin plus gemcitabine vs a cisplatin-based triplet vs non platinum sequential doublets in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a Spanish Lung Cancer Group phase III randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 21: 3207–3213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardizzoni A, Boni L, Tiseo M, Fossella FV, Schiller JH, Paesmans M, Radosavljevic D, Paccagnella A, Zatloukal P, Mazzanti P, Bisset D, Rosell R, CISCA (CISplatin vs CArboplatin) Meta-analysis Group (2007) Cisplatin-vs carboplatin-based chemotherapy in first-line treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: an individual patient data meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 399: 847–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzoli CG, Baker Jr S, Temin S, Pao W, Aliff T, Brahmer J, Johnson DH, Laskin JL, Masters G, Milton D, Nordquist L, Pfister DG, Piantadosi S, Schiller JH, Smith R, Smith TJ, Strawn JR, Trent D, Giaccone G (2009) American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline update on chemotherapy for stage IV non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 27: 6251–6266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldini E, Ardizzoni A, Prochilo T, Cafferata MA, Boni L, Tibaldi C, Neumaier C, Conte PF, Rosso R, Italian Lung Cancer Task Force (2001) Gemcitabine, ifosfamide and navelbine (GIN): activity and safety of a non-platinum-based triplet in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Br J Cancer 85: 1452–1455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boni C, Bisagni G, Savoldi L, Moretti G, Rondini E, Sassi M, Zadro A, De Pas T, Franciosi V, Pazzola A, Vignoli R, Banzi MC, Pajetta V (2000) Gemcitabine, ifosfamide, cisplatin (GIP) for the treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a phase II study of the Italian Oncology Group for Clinical Research (GOIRC). Int J Cancer 87: 724–727 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookmeyer R, Crowley J (1982) A confidence interval for the median survival time. Biometrics 38: 29–41 [Google Scholar]

- Comella P, Frasci G, Panza N, Manzione L, De Cataldis G, Cioffi R, Maiorino L, Micillo E, Lorusso V, Di Rienzo G, Filippelli G, Lamberti A, Natale M, Bilancia D, Nicolella G, Di Nota A, Comella G (2000) Randomized trial comparing cisplatin, gemcitabine, and vinorelbine with either cisplatin and gemcitabine or cisplatin and vinorelbine in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: interim analysis of a phase III trial of the Southern Italy Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 18: 1451–1457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Addario G, Früh M, Reck M, Baumann P, Klepetko W, Felip E, ESMO Guidelines Working Group (2010) Metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 21(Suppl 5): v116–v119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Addario G, Pintilie M, Leighl NB, Feld R, Cerny T, Shepherd FA (2005) Platinum-based vs non-platinum-based chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis of the published literature. J Clin Oncol 23: 2926–2936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delbaldo C, Michiels S, Syz N, Soria JC, Le Chevalier T, Pignon JP (2004) Benefits of adding a drug to a single-agent or a 2-agent chemotherapy regimen in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. JAMA 28: 470–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgoulias V, Ardavanis A, Tsiafaki X, Agelidou A, Mixalopoulou P, Anagnostopoulou O, Ziotopoulos P, Toubis M, Syrigos K, Samaras N, Polyzos A, Christou A, Kakolyris S, Kouroussis C, Androulakis N, Samonis G, Chatzidaki D (2004) Vinorelbine plus cisplatin vs docetaxel plus gemcitabine in advanced non small cell lung cancer: a phase III randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 23: 2937–2945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgoulias V, Papadakis E, Alexopoulos A, Tsiafaki X, Rapti A, Veslemes M, Palamidas P, Vlachonikolis I, Greek Oncology Cooperative Group (GOCG) for Lung Cancer (2001) Platinum-based and non-platinum-based chemotherapy in advanced non small cell lung cancer: a randomized multicenter trial. Lancet 357: 1478–1484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gridelli C, Frontini L, Perrone F, Gallo C, Gulisano M, Cigolari S, Castiglione F, Robbiati SF, Gasparini G, Ianniello GP, Farris A, Locatelli MC, Felletti R, Piazza E (2000) Gemcitabine plus vinorelbine in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: A phase II study of three different doses. Br J Cancer 83: 707–714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gridelli C, Gallo C, Shepherd FA, Illiano A, Piantedosi F, Robbiati SF, Manzione L, Barbera S, Frontini L, Veltri E, Findlay B, Cigolari S, Myers R, Ianniello GP, Gebbia V, Gasparini G, Fava S, Hirsh V, Bezjak A, Seymour L, Perrone F (2003) Gemcitabine plus vinorelbine compared with cisplatin plus vinorelbine or cisplatin plus gemcitabine for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III trial of the Italian GEMVIN investigators and the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol 21: 3025–3034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly K, Crowley J, Bunn Jr PA, Presant CA, Grevstad PK, Moinpour CM, Ramsey SD, Wozniak AJ, Weiss GR, Moore DF, Israel VK, Livingston RB, Gandara DR (2001) Randomized phase III trial of paclitaxel plus carboplatin vs vinorelbine plus cisplatin in the treatment of patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a Southwest Oncology Group trial. J Clin Oncol 19: 3210–3218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosmidis P, Mylonakis N, Nicolaides C, Kalophonos C, Samantas E, Boukovinas J, Fountzilas G, Skarlos D, Economopoulos T, Tsavdaridis D, Papakostas P, Bacoyiannis C, Dimopoulos M (2002) Paclitaxel plus carboplatin vs gemcitabine plus paclitaxel in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 20: 3578–3585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota K, Kawahara M, Ogawara M, Nishiwaki Y, Komuta K, Minato K, Fujita Y, Teramukai S, Fukushima M, Furuse K, Japan Multi-National Trial Organisation (2008) Vinorelbine plus gemcitabine followed by docetaxel vs carboplatin plus paclitaxel in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomised, open-label phase III study. Lancet Oncol 9: 1135–1142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laack E, Dickgreber N, Muller T, Knuth A, Benk J, Lorenz C, Gieseler F, Dürk H, Engel-Riedel W, Dalhoff K, Kortsik C, Graeven U, Burk M, Dierlamm T, Welte T, Burkholder I, Edler L, Hossfeld DK, , German and Swiss Lung Cancer Study Group. Randomized phase III study of gemcitabine and vinorelbine vs gemcitabine, vinorelbine, and cisplatin in the treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: from the German and Swiss Lung Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol 22: 2348–2356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Chevalier T, Scagliotti G, Natale R, Danson S, Rosell R, Stahel R, Thomas P, Rudd RM, Vansteenkiste J, Thatcher N, Manegold C, Pujol JL, van Zandwijk N, Gridelli C, van Meerbeeck JP, Crino L, Brown A, Fitzgerald P, Aristides M, Schiller JH (2005) Efficacy of gemcitabine plus platinum chemotherapy compared with other platinum containing regimens in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis of survival outcomes. Lung Cancer 47: 69–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paccagnella A, Oniga F, Bearz A, Favaretto A, Clerici M, Barbieri F, Riccardi A, Chella A, Tirelli U, Ceresoli G, Tumolo S, Ridolfi R, Biason R, Nicoletto MO, Belloni P, Veglia F, Ghi MG (2006) Adding gemcitabine to paclitaxel/carboplatin combination increases survival in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a phase II-III study. J Clin Oncol 24: 681–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujol JL, Barlesi F, Daures JL (2006) Should chemotherapy combinations for advanced non small cell lung cancer be platinum-based? A meta-analysis of phase III randomized trials. Lung Cancer 51: 35–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajeswaran A, Trojan A, Burnand B, Giannelli M (2008) Efficacy and side effects of cisplatin and carboplatin-based doublet chemotherapeutic regimens vs non-platinum-based doublet chemotherapeutic regimens as first line treatment of metastatic non-small cell lung carcinoma: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Lung Cancer 59: 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler A, Gray R, Perry MC, Brahmer J, Schiller JH, Dowlati A, Lilenbaum R, Johnson DH (2006) Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 355: 2542–2550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scagliotti GV, De Marinis F, Rinaldi M, Crinò L, Gridelli C, Ricci S, Matano E, Boni C, Marangolo M, Failla G, Altavilla G, Adamo V, Ceribelli A, Clerici M, Di Costanzo F, Frontini L, Tonato M, Italian Lung Cancer Project (2002) Phase III randomized trial comparing three platinum-based doublets in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 20: 4285–4291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scagliotti GV, Parikh P, von Pawel J, Biesma B, Vansteenkiste J, Manegold C, Serwatowski P, Gatzemeier U, Digumarti R, Zukin M, Lee JS, Mellemgaard A, Park K, Patil S, Rolski J, Goksel T, de Marinis F, Simms L, Sugarman KP, Gandara D (2008) Phase III study comparing cisplatin plus gemcitabine with cisplatin plus pemetrexed in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 26: 3543–3551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller JH, Harrington D, Belani CP, Langer C, Sandler A, Krook J, Zhu J, Johnson DH, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (2002) Comparison of four chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 346: 92–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit EF, van Meerbeeck JP, Lianes P, Debruyne C, Legrand C, Schramel F, Smit H, Gaafar R, Biesma B, Manegold C, Neymark N, Giaccone G (2003) Three-arm randomized study of two cisplatin based regimens and paclitaxel plus gemcitabine in advanced non small cell lung cancer: a phase III trial of the European organization for research and treatment of cancer. Lung Cancer Group EORTC 08975. J Clin Oncol 21: 3909–3917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, Verweij J, Van Glabbeke M, van Oosterom AT, Christian MC, Gwyther SG (2000) New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst 92: 205–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiseo M, Martelli O, Mancuso A, Sormani MP, Bruzzi P, Di Salvia R, De Marinis F, Ardizzoni A (2007) Short hydration regimen and nephrotoxicity of intermediate-high dose cisplatin-based chemotherapy for outpatient treatment in lung cancer and mesothelioma. Tumori 93: 138–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermorken JB, Remenar E, van Herpen C, Gorlia T, Mesia R, Degardin M, Stewart JS, Jelic S, Betka J, Preiss JH, van den Weyngaert D, Awada A, Cupissol D, Kienzer HR, Rey A, Desaunois I, Bernier J, Lefebvre JL, EORTC 24971/TAX 323 Study Group (2007) Cisplatin, fluorouracil, and docetaxel in unresectable head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med 357: 1695–1704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.