Background: Leukocyte function is regulated by the balance between activating and inhibitory signals deliver by immune receptors.

Results: We present the cloning and molecular characterization of a novel CD300 member, CD300d.

Conclusion: The function of CD300d is related to the regulation of the expression and function of other CD300 receptors.

Significance: A new mechanism of regulation of myeloid cell activation is described.

Keywords: Cell Surface Receptor, Cloning, Innate Immunity, Myeloid Cell, Receptor Regulation, CD300

Abstract

Herein we present the cloning and molecular characterization of CD300d, a member of the human CD300 family of immune receptors. CD300d cDNA was cloned from RNA obtained from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and RT-PCR revealed the gene to be expressed in cells of myeloid lineage. The cloned cDNA encoded for a type I protein with a single extracellular Ig V-type domain and a predicted molecular mass of 21.5 kDa. The short cytoplasmic tail is lacking in any known signaling motif, but there is a negatively charged residue (glutamic acid) within the transmembrane domain. CD300d forms complexes with the CD300 family members, with the exception of CD300c. Contrary to other activating members of the CD300 family of receptors, surface expression of CD300d in COS-7-transfected cells required the presence of an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activating motif-bearing adaptor (FcϵRγ). Accordingly, we found that CD300d was able to recruit FcϵRγ. Unexpectedly, we could not detect CD300d on the surface of cells expressing FcϵRγ, suggesting the existence of unknown mechanisms regulating the trafficking of this molecule. The presence of other CD300 molecules also did not modify the intracellular expression of CD300d. In fact, the presence of CD300d decreased the levels of surface expression of CD300f but not CD300c. Our data suggest that the function of CD300d would be related to the regulation of the expression of other CD300 molecules and the composition of CD300 complexes on the cell surface.

Introduction

Leukocyte function is regulated by the final balance between activating and inhibitory signals produced continuously by immunoreceptors mostly present on the cell surface. These receptors, which usually belong to multigenic families, include molecules with extracellular C-type lectin-like or immunoglobulin-like folds (1–3). Inhibitory immunoreceptors display long cytoplasmic tails containing immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs. After receptor engagement by their ligands, tyrosine residues within immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs are phosphorylated, becoming docking sites for the recruitment of Src homology 2 domain-containing tyrosine phosphatases, such as SHP-1 and SHIP. Upon recruitment by inhibitory receptors, phosphatases become active and dephosphorylate key intracellular substrates involved in the initiation and amplification of activating responses (2). In contrast, activating receptors usually present short cytoplasmic tails lacking any signaling motifs. Alternatively, they present a positively charged amino acid residue within their transmembrane domain that enables the interaction with immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activating motif (ITAM)5-bearing adaptor proteins (FcϵRγ, CD3ζ, and DAP12 (DNAX-activating protein of 12 kDa)), which contain a complementary negative charge in the same domain. Ligand-induced phosphorylation of ITAMs leads to the recruitment of tandem Src homology 2 domain-containing tyrosine kinases, such as Syk and ZAP-70, to transduce activating signals (1).

The human CD300 family of immunoreceptors belongs to the superfamily of immunoglobulin receptors, and the genes that encode for the different members are clustered on human chromosome 17q25.1 (4, 5). All of them are found exclusively in myeloid cells, with the exception of CD300a that is additionally expressed in certain subsets of T and NK cells. CD300 receptors present an extracellular V-type immunoglobulin-like domain with an additional pair of cysteine residues, a transmembrane region, and a cytoplasmic tail. Up to now, five members of the family have been identified and fully characterized (6–9). Although initially it seemed that these molecules fitted the classical activating/inhibitory immunoreceptor model, now it is clear that this family presents a more complex behavior than expected. CD300a and CD300f receptors can be classified structurally as inhibitory receptors due to the presence of immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs in their cytoplasmic tails. Indeed, both molecules are able to bind SHP-1 phosphatase and consequently block activating signals promoted by activating receptors (6, 8). Surprisingly, CD300f has the capability to recruit Grb2 and the PI3K p85α subunit (10). Accordingly, a dual activating/inhibitory function has been proposed for this receptor. The mechanism(s) regulating CD300f duality is not yet fully understood. CD300b and CD300e receptors interact with the ITAM-bearing adaptor DAP12 through charge complementation between transmembrane regions and deliver activating signals after receptor engagement with specific antibodies (8, 9, 11). However, CD300b receptor is a non-classical activating receptor because, in addition to DAP12, it recruits the scaffold protein Grb2 through a tyrosine-based motif present in the cytoplasmic tail. The recruitments of both signaling molecules are independent events and define two different signaling pathways (9). Finally, CD300c, the first cloned member of the CD300 family, displays a short cytoplasmic tail in combination with a transmembrane region bearing a negatively charged residue, which theoretically would avoid transmembrane charge complementation with the known adaptor polypeptides (7). Nevertheless, we have shown recently that CD300c is able to recruit FcϵRγ polypeptide through a different mechanism and consequently acts as an activating receptor (12). In addition, we have demonstrated that the receptors of this family interact extracellularly, forming homo- and heterosignaling complexes (12). This feature has not been reported in other immunoreceptor clusters and constitutes a novel mechanism to regulate the leukocyte function.

In this study, we report the cloning and molecular characterization of CD300d, the sixth member of the human CD300 family. Regarding its function, our data suggest that CD300d would regulate the expression of other CD300 molecules and the composition of CD300 complexes on the cell surface.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cells and Reagents

RBL-2H3, HeLa, and COS-7 cells were grown in DMEM containing 10% heat-inactivated FCS, 2 mm glutamine, 1 mm sodium pyruvate, 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Human recombinant GM-CSF, IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, and IFN-γ were purchased from Peprotech, and LPS (Salmonella enterica serotype thyphimurium) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Biotinylated anti-HA (12CA5) mAb was purchased from Roche Applied Science, anti-HA (1.1) mAb was from Covance, and anti-FcϵRIγ subunit rabbit polyclonal antibody was from Millipore. HRP-linked anti-FLAG M2® mAb was from Sigma. HRP-conjugated anti-mouse goat polyclonal and anti-rabbit donkey polyclonal antibody were obtained from GE Healthcare. FITC-conjugated anti-mouse rabbit polyclonal antibody was from DAKO. Streptavidin-HRP was purchased from Roche Applied Science. Anti-human GRP-78 (H129) rabbit polyclonal antibody was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated anti-rabbit was from Molecular Probes. Anti-HA (12CA5) mAb and anti-Myc (9E10) mAb were described previously (12).

Cloning of Human CD300d and DNA Constructs

Constructs used in this study were generated by PCR under the following conditions: 94 °C for 3 min and 30 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 1 min using Pfu DNA polymerase (Promega). PCR products were resolved in 1% agarose gels, visualized by ethidium bromide staining, and further confirmed by DNA sequencing under Big DyeTM cycling conditions on an Applied Biosystems 3730xl DNA Analyzer (Macrogen Inc.). Details have been summarized in supplemental Table 1. Full-length CD300d (including 5′- and 3′-untranslated regions) was amplified from human monocyte cDNA and cloned into pcDNA3.1-V5-His TOPO (Invitrogen), and then the molecule without signal peptide was subcloned into pDisplay and pCDNA3-FLAG vectors. pDisplay/CD300d (R173S, E173A, and F168L/F170V) and pcDNA3-FLAG/FcϵRγ D29A substitution mutants were generated by PCR amplification with mutagenic oligonucleotides according to the instructions of the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). Chimerical molecules CD300c/d (immunoglobulin domain, stem, and transmembrane region from hCD300c and the cytoplasmic tail of hCD300d) and CD300d/f (immunoglobulin domain and stem region of hCD300d and the transmembrane and cytoplasmic tail of hCD300f) were generated by PCR amplification and annealing of the overlapping ends and cloned into the pDisplay vector. Full-length CD300c, CD300d, and CD300f were cloned into the pEGFP-N3 vector. pDisplay/CD300a (12), -CD300b (9), -CD300c WT and ΔCyto (del209–224aa) (12), -CD300e (8), and -CD300f (13); pCDNA3-FLAG/CD300a, -CD300b, -CD300c, -CD300e, -CD300f, and -FcϵRγ (12); pcDNA3-Flag/DAP12 (9); and pBabePuro-2xMyc/CD300c (12) were described previously.

Real-time PCR

RNA from cell lines was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), treated with DNAse I amplification grade (Invitrogen), and retrotranscribed using the High-Capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturers' instructions. Real-time PCR for CD300d transcript detection was performed using TaqMan gene expression assay (Applied Biosystems) on an ABI-Prism 7500 sequence detector (Applied Biosystems). 18S amplification control was used for cycle normalization. Data were analyzed with 7500 SDS Software (Applied Biosystems). All PCRs were set up in triplicates.

Mononuclear Cell Isolation and Monocyte Differentiation

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were purified from buffy coats provided by the Banc de Sang i Teixits (Barcelona, Spain). Samples were diluted 1:4 with PBS, and mononuclear cells were isolated by Ficoll-Paque (GE Healthcare) density gradient centrifugation. For isolation of monocytes, PBMC were resuspended at a final concentration of 10 × 106/ml in RPMI 1640 with 10% FCS and allowed to adhere to plastic for 1 h at 37 °C. Non-adherent cells were removed, and attached cells were washed twice with PBS. Monocyte-enriched cell populations were then cultured for 5 days in the presence of 20 ng/ml GM-CSF. Cells were cultured for an additional 2 days in complete RPMI 1640 medium in the presence of the following cytokines: 25 ng/ml IFN-γ and 100 ng/ml LPS (M1ca); 20 ng/ml IL-4 (M2a/IL-4); 20 ng/ml IL-13 (M2a/IL-13); or 20 ng/ml IL-10 (M2c). Cell differentiation was monitored by assessing specific cell surface markers. Isolation of NK, T, and B cells and granulocytes from human PBMC was carried out as described (9, 14).

Cell Transfections

COS-7 cells (6 × 105) were transiently transfected using LyoVec (Invivogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For the generation of RBL-2H3 stable transfectants, 20 × 106 cells were electroporated in the presence of 20 μg of linearized construct at 280 V and 950 microfarads in a Gene Pulser electroporator (Bio-Rad). Transfectants were selected and maintained in culture with 1 mg/ml G418 (Invitrogen) or 1 μg/ml puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich).

Flow Cytometry and Immunofluorescence

Cell surface expression of the desired molecules was tested by indirect immunofluorescence following standard techniques. Samples were analyzed on a FACSCalibur using the CellQuest Software (BD Biosciences). For immunofluorescence, COS-7 cells were cultured and transfected on glass coverslips. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 5 min, and stained with DAPI for 1 min. Images were captured using a FV Olympus confocal microscope.

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blotting

Cells were lysed at 4 °C for 15 min using 1% Triton X-100-containing buffer described previously (15). Cell lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C and further precleared for 1 h at 4 °C using 20 μl of protein G-Sepharose beads (Amersham Biosciences) and 5 μg of mouse IgG (Sigma-Aldrich). Two additional preclearings were carried out for 30 min at 4 °C with 20 μl of protein G-Sepharose beads. For immunoprecipitations, precleared lysates were incubated with 30 μl of protein G-Sepharose beads and 1 μg of antibody for 3 h at 4 °C. Proteins in the crude lysates (2%) and immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF filters (Millipore). Filters were blocked for 1 h with 5% skim milk or 3% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich) and then probed with the indicated antibodies. Bound antibodies were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Pierce).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive data were expressed as the arithmetic mean ± S.E. The GraphPad Prism statistical package (version 5.0) was used to investigate group differences by unpaired Student's t test. p values are indicated for statistically different means.

RESULTS

Cloning and Sequence Analysis of Human CD300d

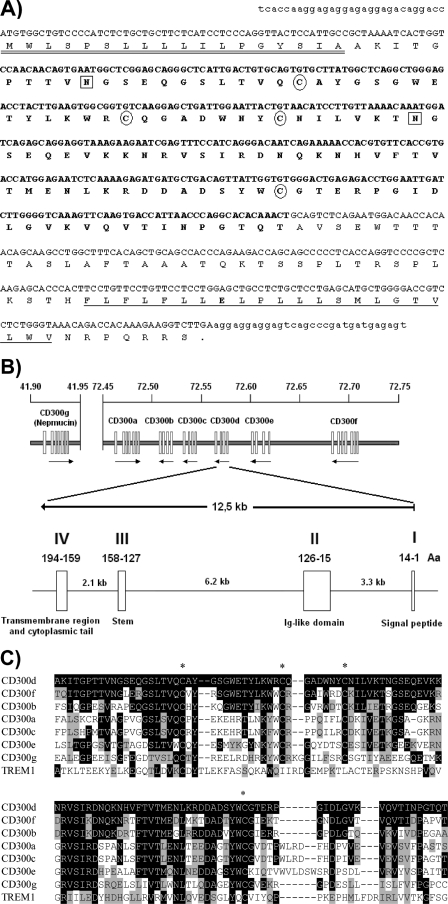

With the aim of identifying new members of the CD300 family, we used the sequences of known human CD300 molecules to BLAST the Ensembl genome database. The search resulted in a cDNA encoding for a novel putative CD300 receptor termed CD300d. We designed primers to amplify the putative nucleotide sequence from cDNA obtained from human monocytes. The 644-bp PCR product contained an open reading frame of 585 bp encoding for a protein of 194 aa with a predicted molecular mass of 21.5 kDa (EF137868) (Fig. 1A). Sequence analysis revealed CD300d as a type I transmembrane receptor driven by a signal peptide 18 aa in length (SignalP 3.0 server). The extracellular region of CD300d presents a single Ig V-type domain followed by a 41-aa membrane-proximal or stem region. The Ig domain contains two potential N-glycosylation sites, whereas the stem area displays 17 putative O-glycosylation sites (NetNGlyc 1.0 and NetOGlyc 3.1 servers). CD300d, like all the CD300 family members, displays an additional pair of cysteines within the immunoglobulin domain (Cys50 and Cys58). The transmembrane domain presents a negatively charged residue (glutamic acid) in a central position and is followed by a very short cytoplasmic tail (7 residues) without any known signaling motif (Fig. 1A). Through alignment of cDNA and genomic sequences, we determined CD300d gene organization (Fig. 1B). The gene spans a 12.5-kb region of chromosome 17 (17q25.1) and is composed of four exons. The first exon encodes for the 5′-untranslated region and the protein's signal peptide, whereas the Ig domain is encoded by exon 2, the membrane-proximal region is encoded by exon 3, and the transmembrane domain and cytoplasmic tail of CD300d are encoded by exon 4. We analyzed the degree of homology of the extracellular Ig domain of CD300d with sequences of CD300 family members and TREM-1 (triggering receptor expressed by myeloid cells 1), a closely related immunoreceptor. The CD300f Ig domain showed the highest homology (71.4% identity) with CD300d, whereas other members of the family, such as CD300b (58.9%), CD300e (41.1%), CD300c (41.1%), and CD300a (39.2%), presented less but still significant homology (Fig. 1C). A lower degree of protein sequence homology was detected between the Ig domains of CD300d and other related proteins, such as CD300Lg and TREM-1 (31.2 and 17.8% respectively). The amino acid sequences of the Ig-like domain of all human CD300 molecules and TREM-1 were aligned and used to reconstruct a molecular phylogenetic tree (data not shown) using the Phylogeny.fr platform (16). As expected from the identities mentioned above, CD300d is closely related to CD300f and CD300b. Interestingly, when we analyzed the homologies among the exons encoding for the transmembrane and intracellular domains of CD300 molecules, CD300c was the closest to CD300d. These data suggest that multiple gene duplications of CD300-related genes might have occurred along evolution, probably from a common ancestor with CD300Lg.

FIGURE 1.

A, predicted nucleotide and amino acid sequence of CD300d (EF137868). The nucleotide sequence of human CD300d containing an open reading frame of 585 bp is shown in capital letters. The 5′- and 3′-untranslated region is shown in lowercase. The predicted amino acid sequence is shown below the nucleotide sequence. The putative signal peptide is double underlined, the Ig-like domain is in boldface type, and the transmembrane domain is single underlined. Potential N-glycosylation sites are boxed, cysteine residues involved in the Ig-like domain fold are circled, and the transmembrane charged glutamic acid is in boldface type. B, CD300d gene organization. Shown is a schematic of the organization of the CD300 locus at chromosomal region 17q25.1. CD300d genomic organization is shown below. Exons are represented by boxes (respective lengths in coding amino acids and domain architecture are shown); introns are represented by connecting lines. C, alignment of CD300d Ig-like domain with Ig domains from CD300 proteins and TREM-1. Residues identical to those present in CD300d are shown on a black background, and similar residues are on a gray background. Conserved cysteine residues are marked with asterisks.

CD300d Expression Is Restricted to Myeloid Lineage

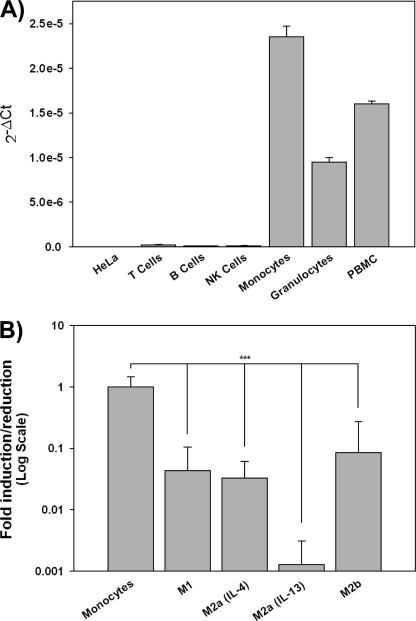

To determine the distribution of CD300d transcript, we performed real-time PCR on PBMC and purified blood populations as well as diverse hematopoietic cell lines. CD300d was found abundantly in PBMC but exclusively in the myeloid compartment, including monocyte and granulocyte populations (Fig. 2A). No cDNA amplification was observed in T, B, and NK lymphocytes. Similarly to CD300e, CD300d transcript was absent in cell lines from myeloid origin (THP-1, U937, HL-60, and MonoMac6) in basal conditions (data not shown). Based on these data, CD300d expression seems to be restricted to cells of myeloid lineage, as we observed previously for CD300b, CD300e, and CD300f (8, 9, 13). To further analyze the pattern of expression of CD300d in monocyte-derived macrophages, we isolated monocytes from healthy donors and cultured them in the presence of GM-CSF to differentiate monocytes into naive macrophages. Cells were further treated with cytokines to obtain activated macrophages from the different subtypes: IFN-γ (M1), IL-4 or IL-13 (M2a/IL-4 or M2a/IL-13), or IL-10 (M2b). We analyzed the expression of CD300d transcripts by real-time PCR. Amplification data showed a significant decrease of CD300d expression in all types of in vitro derived macrophages when compared with freshly isolated monocytes. In fact, CD300d transcript was undetectable in IL-13-driven type II macrophages (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

CD300d mRNA is detected by RT-PCR in cells of myeloid lineage. Shown is TaqMan analysis of CD300d expression in human purified leukocyte populations (A) and in vitro differentiated macrophage populations (n = 7) (B). ***, p ≤ 0.005. Error bars, S.E.

Molecular/Biochemical Characterization of CD300d

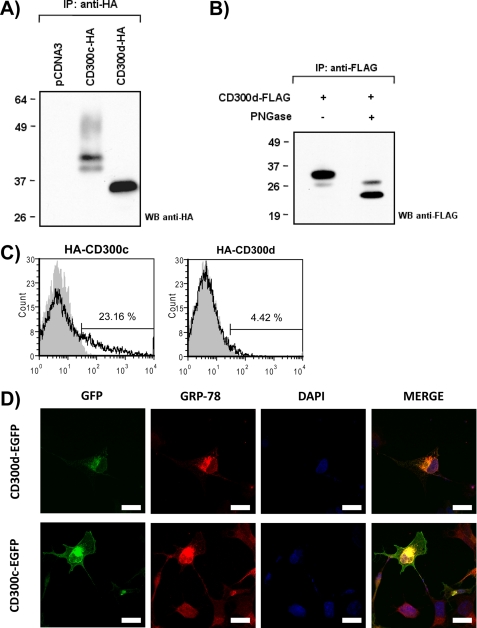

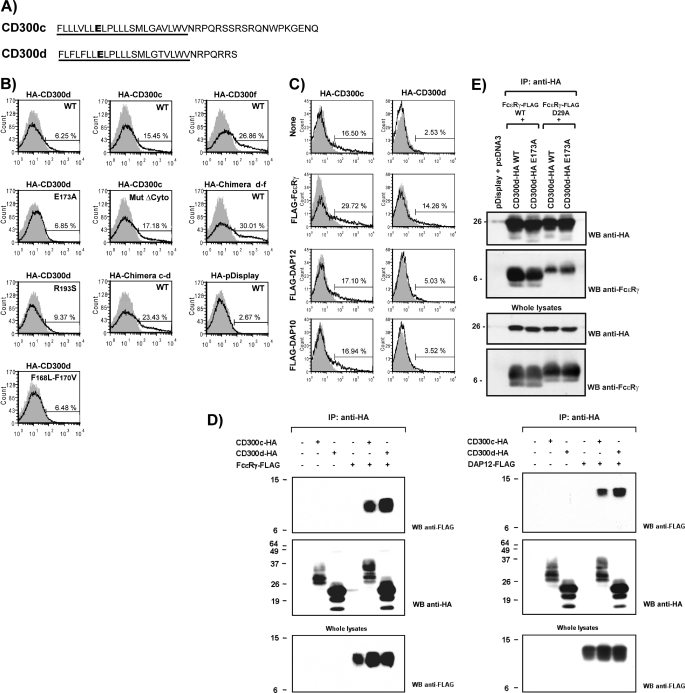

The cDNA encoding for CD300d was cloned in the pDisplay vector in order to tag the protein with an N terminus HA epitope and transiently transfect COS-7 cells. HA-CD300c was used as control, due to the high homology between both molecules in terms of predicted molecular weight and structure. Forty-eight hours post-transfection, cells were lysed and subjected to anti-HA immunoprecipitation and SDS-PAGE analysis. Although CD300d had a predicted molecular weight of 21.5 kDa, the molecule appeared as a discrete pattern of two bands around 30 and 34 kDa. CD300c showed a more complex pattern of bands with a retarded electrophoretic mobility (Fig. 3A). CD300d apparent molecular mass was reduced after in vitro N-deglycosylation with peptide:N-glycosidase F, indicating the presence of N-linked sugars in the protein backbone (Fig. 3B). Surprisingly, surface expression of HA-CD300d was almost undetectable on transfected COS-7 cells when assessed by flow cytometry, whereas around 25% of HA-CD300c-transfected cells were positive for HA staining (Fig. 3C). It is noteworthy that we could detect comparable amounts of both molecules when the expression was monitored by Western blot (Fig. 3A). This finding indicated that HA-CD300d was expressed efficiently, but the molecule was retained intracellularly and its traffic toward the cell membrane was blocked. Considering that CD300d N-deglycosylation resulted in a molecular electrophoretic pattern close to the polypeptidic backbone, it was feasible that the receptor was blocked in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Accordingly, O-glycans could not be transferred to the immature protein in the Golgi apparatus, explaining the different mobility of CD300d in SDS-polyacrylamide gels when compared with CD300c. To test the ER blockade, we fused CD300d receptor to GFP to allow protein visualization by means of fluorescence microscopy. CD300d-GFP was markedly concentrated in a perinuclear region upon transfection in COS-7 cells co-localizing with the ER marker BIP/GRP-78 (17) (Fig. 3D). Conversely, cells transfected with CD300c-EGFP showed a more disseminated pattern of expression compatible with a cell surface localization (Fig. 3D). The fact that CD300d was retained intracellularly when the expression of all CD300 molecules was driven by the same promoter and an exogenous signal peptide suggested the existence of a retention motif in the sequence of CD300d. We noted that 6 of 7 aa present in the CD300d cytoplasmic tail were identically represented in CD300c. Only position +6 showed a difference between both receptors, being a serine in CD300c and an arginine in CD300d (Fig. 4A). In order to determine whether this residue constituted an ER retention motif, we carried out an HA-CD300d substitution mutation. CD300d R137S was unable to reach the cell surface upon transfection (Fig. 4B, left), indicating that other domains in CD300d had to be involved in the intracellular retention of this molecule. Next, we evaluated the possibility that CD300c had an ER retrieval motif within its 12-aa-long cytoplasmic tail. With this purpose, we used a CD300c deletion mutant lacking the cytoplasmic tail (CD300c Δcyto) to evaluate its access to the cell surface compared with CD300c WT (12). HA staining on COS-7-transfected cells showed no differences in the levels of expression of both constructs (Fig. 4B, middle). Then we made a chimerical protein containing the complete CD300d extracellular sequence and the transmembrane and cytoplasmic tail of the CD300f receptor (CD300d/f). This construct was detected on the surface of COS-7-transfected cells similarly to CD300f WT, indicating that the CD300d immunoglobulin domain and/or stem region were not responsible for CD300d intracellular entrapment (Fig. 4B, right). Next we generated a new chimerical protein harboring the extracellular and transmembrane region of CD300c and the cytoplasmic tail of CD300d (CD300c/d). As we show in Fig. 4B, this construct was detected on the surface of transfected cells equally well as CD300c. This finding suggested that the CD300d transmembrane region was involved in the intracellular retention. We noted the presence of two phenylalanine residues within the CD300d transmembrane sequence that were not present in the same region of CD300c (Fig. 4A). Thus, we substituted both residues in CD300d by leucine and valine residues to generate a new CD300d construct, (F168L/F170V) with a transmembrane domain almost identically to CD300c. The substitution of both phenylalanine residues did not modify the intracellular expression of CD300d. Similarly, substitution of the CD300d transmembrane glutamic acid residue by an alanine (E173A) did not enhance the surface expression of the receptor (Fig. 4B, left). These data strongly suggest the existence of diverse retention-retrieval motifs present in more than one domain of CD300d that might be responsible for the intracellular retention observed for this protein.

FIGURE 3.

CD300d is retained intracellularly. COS-7 cells were transiently transfected with HA-tagged CD300d and CD300c. A, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA (11) mAb and analyzed by 12% SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions. Proteins were transferred to a PVDF filter and probed with anti-HA (12CA5). B, immunoprecipitated HA-CD300d was subjected to peptide:N-glycosidase F (PNGase F) (New England Biolabs) treatment in non-denaturing conditions before being transferred and probed with anti-HA. C, surface expression was monitored by flow cytometry using anti-HA (12CA5) mAb (white histogram) and an isotypic mAb as a negative control (gray histogram). D, COS-7 cells were transfected with CD300d-EGFP, CD300f-EGFP, and CD300c-EGFP, and their expression was analyzed by a confocal microscope. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI, and endoplasmic reticulum was stained with anti-Grp-78 antibody. Scale bar, 20 μm. IP, immunoprecipitation; WB, Western blot.

FIGURE 4.

CD300d associates with FcϵRγ transmembrane adaptor and translocates to the cell surface in COS-7 cells. A, CD300d and CD300c transmembrane and cytoplasmic domain comparison. Transmembrane domains are underlined, and transmembrane glutamic residue is shown in boldface type. B and C, COS-7 cells were transiently transfected with HA-tagged CD300c, CD300d, and CD300f WT or mutant constructs and/or FLAG-tagged transmembrane adaptor molecules. Forty-eight hours post-transfection, cells were subjected to flow cytometry to assess the cell surface expression of the desired molecules. CD300 receptors were stained using anti-HA (12CA5) (white histograms). An isotypic mAb was used as negative control (gray histograms). D and E, transfected COS-7 cells lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA (11) mAb. Proteins were analyzed in 15% SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions, transferred to PVDF, and probed with the indicated antibodies. Whole cell lysates (2%) were included as controls. IP, immunoprecipitation; WB, Western blot.

CD300d Recruits ITAM-bearing Adaptor FcϵRγ

We have shown recently that CD300c is able to deliver activating signals through the recruitment of the ITAM-bearing adaptor FcϵRγ (12). The binding between CD300c and FcϵRγ was not based on the classical positive-negative charge complementation at the transmembrane region found in most of the activating immunoreceptors. In fact, CD300c transmembrane glutamic acid, which was shown to be essential for the functionality of the receptor, was not required for FcϵRγ recruitment (12). CD300c is localized on the cell surface in the absence of FcϵRγ, but co-transfection with the adaptor polypeptide enhances its surface expression (Fig. 4C). Due to the structural similarity between CD300c and CD300d, we decided to check whether co-transfection of CD300d with transmembrane adaptor proteins could impair its ER blockade. FcϵRγ enabled the receptor's surface expression, whereas other myeloid transmembrane adaptor molecules, such as DAP12 or DAP10, had slight or no effect on CD300d expression (Fig. 4C). It is worth mentioning that the cell surface expression of the transmembrane polypeptides remained constant (supplemental Fig. 1). Next, we explored whether this effect occurred as consequence of a direct interaction between both molecules. FcϵRγ immunoprecipitated together with CD300d receptor in COS-7 cells (Fig. 4D). Indeed, CD300d recruited FcϵRγ as efficiently as CD300c (Fig. 4D). In parallel, we demonstrated that CD300d was able to recruit the adaptor DAP12 as efficiently as CD300c. Finally, we analyzed the role of the negative residues within the transmembrane sequences of both CD300d and FcϵRγ in the interaction between both proteins. Whereas the glutamic acid present in CD300d seemed not to be required for the interaction between the two proteins, substitution of the negative charge within the transmembrane domain of FcϵRγ strongly decreased the interaction (Fig. 4E).

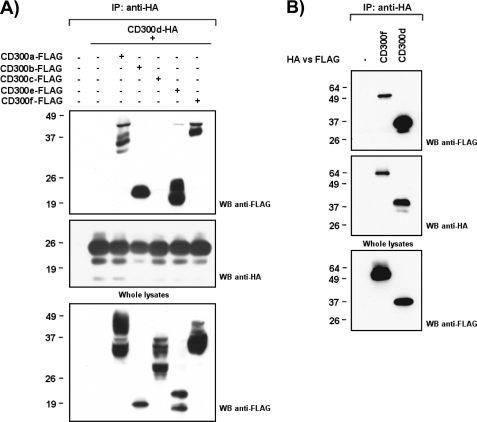

CD300d Interacts with All CD300 Family Members with Exception of CD300c

CD300 receptors are able to interact with each other, even with themselves, forming both homo- and heterodimers. These complexes are formed intracellularly, and the combination of CD300 receptors in a complex differentially modulates their signaling outcome (12). The interactoma between CD300 receptors was determined for all members except for CD300d, which was not cloned at that moment. Surprisingly, CD300d formed complexes with all of the members of the CD300 family with the exception of CD300c in the COS-7 overexpression system (Fig. 5A). In addition, CD300d was able to form homocomplexes (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

CD300d interacts with all members of the CD300 family with the exception of CD300c. HA-CD300d was transiently transfected in COS-7 cells in combination with FLAG-tagged CD300 receptors (CD300a, CD300b, CD300c, CD300e, and CD300f) (A) or CD300d (B). Cell lysates (Triton X-100, 1%) were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA (11) mAb. Filters were probed with the indicated antibodies. Whole cell lysates (2%) were included as controls. IP, immunoprecipitation; WB, Western blot.

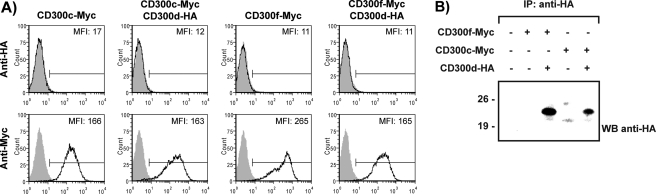

CD300d Stably Expressed in RBL-2H3 Cells Is Not Present on Cell Surface

We have used extensively the RBL-2H3 cell line to analyze the function of CD300 receptors (8, 10, 12, 13). We stably transfected this cell line with an HA-tagged form of CD300d receptor to be able to further analyze its function. Although RBL-2H3 cells express FcϵRγ, which was shown to be essential for CD300d surface export, the receptor could not be detected by flow cytometry. However, we could detect the presence of the protein by Western blot (data not shown). Next, we reasoned that in RBL-2H3 cells, CD300d export might rely on the presence of other CD300 molecules rather than on transmembrane adaptor proteins. In order to check this hypothesis, we transfected RBL-2H3 cells stably expressing Myc-CD300f or Myc-CD300c with HA-CD300d receptor. We expected that the formation of complexes between CD300f and CD300d would force CD300d expression on the cell membrane. By contrast, because CD300c and CD300d did not interact, our prediction was that no surface expression of CD300d would be detected. CD300d was not detected on the surface of RBL-2H3 independently of the CD300 receptor content. However, we noticed that CD300f expression was diminished when cells had been co-transfected with CD300d, whereas expression of CD300c was similar both in the presence and absence of CD300d (Fig. 6A). It is worthy of mention that both cell lines were successfully transfected with CD300d as determined by Western blot techniques (Fig. 6B).

FIGURE 6.

Expression of CD300d molecules in transfected RBL-2H3 cells. RBL-2H3 cells stably expressing Myc-CD300f or Myc-CD300c on the cell membrane were transfected with HA-CD300d. A, surface expression of CD300 molecules was monitored by flow cytometry using anti-HA (12CA5) or anti-Myc (9E7) (white histograms) or an isotypic mAb as a negative control (gray histograms). B, cell lysates (CHAPS, 1%) were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA (11) mAb and analyzed by 12% SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions. Proteins were transferred to PVDF filters and probed with the indicated antibodies. IP, immunoprecipitation; WB, Western blot.

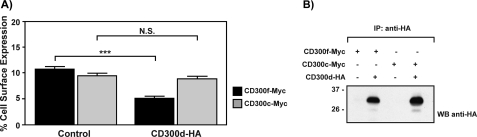

CD300d Down-regulates CD300f Surface Expression in Transiently Transfected COS-7 Cells

The reduced levels of CD300f in the cell surface in the presence of CD300d pointed out the possibility that CD300d function would be to negatively regulate the expression of CD300 molecules on the cell surface. With this aim, we measured the cell surface levels of CD300f and CD300c both in the presence and absence of CD300d. Cotransfection of CD300d significantly decreased the presence of CD300f on the cell surface (Fig. 7A). As expected, CD300d had no effect on CD300c cell surface expression. Again, equivalent amounts of CD300d were detected in transfected cells when assessed by Western blotting (Fig. 7B).

FIGURE 7.

CD300d reduces CD300f cell surface expression in COS-7 cells. Cells were transiently transfected with the indicated CD300 constructs and assessed for flow cytometry (A) and Western blot (B) as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Each assay was set up in triplicate. The result is a mean of three independent experiments. ***, p ≤ 0.0005; N.S, non-significant. Error bars, S.E.

DISCUSSION

With the cloning and characterization of CD300d, we have completed the description of the human CD300 locus. As shown in Fig. 1B, six members (CD300a–CD300f) are clustered in a 450-kb region of human chromosome 17. Some kb upstream, there is a seventh gene encoding for a receptor named nepmucin/CD300Lg (18, 19). Despite the homology of the CD300Lg Ig domain with the rest of the CD300 members, there are multiple features that make this receptor a distant member of the family. CD300Lg is the only member containing an extracellular mucin-like domain. The cellular and tissue distribution of CD300Lg is restricted to endothelial cells, and its role in L-selectin-dependent lymphocyte rolling and adhesion is totally unrelated to the activating/inhibitory capabilities of CD300 immunoreceptors.

The most interesting finding concerning the CD300d receptor is its inability to reach the cell membrane when transfected in multiple cell types. CD300d was retained intracellularly and more specifically within the ER. Retention within this organelle is partly aided by the linear signals -KDEL KKXX, -K(X)KXX, which represent well characterized ER localization signals for lumenal and membrane proteins, respectively. However, other motifs less well characterized have been implicated in this process. Type I transmembrane proteins display KKXX or dileucine (LL) motifs within their cytoplasmic tails, whereas type II molecules bear arginine-based motifs at the N terminus of the transmembrane domain. Interestingly, at least two type I proteins, VIP36-like and TMX4, have been shown to present arginine-based ER localization motifs within their cytoplasmic tails (20, 21). CD300d sequence analysis revealed the presence of a diarginine motif within its cytoplasmic tail differentially to CD300c. However, disruption of this motif by mutagenesis was not conducive to CD300d surface expression. Protein export from ER is a selective process driven by COPII-coated transport vesicles and dictated by short, linear sequences called ER export motifs (22). These motifs interact with components of the transport vesicles, leading to increased concentration of cargoes in ER exit sites and the subsequent recruitment onto the COPII vesicles. Of various ER export motifs identified, the diacidic motifs have been found in the cytoplasmic and membrane-distal C termini of several membrane proteins (23). The CD300d cytoplasmic tail was ruled out to regulate the trafficking of the receptor due to the fact that the remaining residues within this unit were coincident with CD300c. Additionally, CD300 receptors do not seem to bear ER release motifs within intracellular domains because CD300c and CD300f cytoplasmic deletion mutants maintained a cell surface phenotype (10, 12).

Of special interest is the case of the high affinity receptor for IgE (FcϵRI). In humans, this receptor is found in two alternative forms. The trimeric form is composed by the IgE-binding α subunit (FcϵRα) and a disulfide-linked homodimer of γ chains, whereas the tetrameric form contains an additional tetraspanning β chain (FcϵRβ) (24). FcϵRα contains an acidic residue in its transmembrane domain and a short cytoplasmic tail, similarly to CD300c and CD300d. FcϵRα displays two dileucine ER retention motifs in its cytoplasmic tail, but they are masked by the association with FcϵRγ, allowing its targeting to the cell membrane (25). Nevertheless, this regulation does not occur constitutively because in eosinophils and megakaryocytes, FcϵRα is accumulated in intracellular compartments despite the presence of FcϵRγ in those cells (26, 27). It is of note that additional mechanisms controlling the surface expression of FcϵRα related to its signal peptide (28) and to the N-glycosylation of asparagine residues within its immunoglobulin domain have been described (29). Signal peptide is not responsible for CD300d retention. Entrapment occurred equivalently using three different constructs in which the receptor was driven by different signal peptides: Igκ-chain leader sequence in pDisplay, CD8α leader sequence in pCDNA3-FLAG, and its own signal peptide in pEGFP-N3. The extracellular domain might also be ruled out because substitution of Ig domain and stem regions of CD300f by CD300d resulted in a chimerical protein able to reach the cell membrane. Our experiments with chimerical proteins point out to the transmembrane domain of CD300d as the ER retention unit, but the substitutions of the two phenylalanine residues and the glutamic acid present in this region were not able to induce the trafficking toward the cell surface. Taken together, our data suggest a complex scenario were the combination of different retention-retrieval motifs in different domains of CD300d might be responsible for the intracellular location of this protein.

The presence of FcϵRγ was able to overcome CD300d ER retention in COS-7 cells, whereas no receptor was detected in the surface of RBL-2H3, where FcϵRγ is endogenously expressed (12). FcϵRγ could mask CD300d putative retention motifs in a similar way to what has been described for FcϵRα. In addition, it has been suggested that transmembrane adaptor proteins might act not only as signaling modules but also as chaperones for certain immunoreceptors. Early events in the folding of the receptor are probably rate-limiting, and receptor folding intermediates are retained in the ER until they can adopt the correct conformation and the fully glycosylated pattern. The formation of stable receptor-adaptor modules is thought to assist this process and prevent intracellular degradation. This is the case for NKG2C and Ly-49, whose expression in the membrane is dependent on DAP12 (30, 31). However, it is of note that all CD300-activating members (CD300b, CD300c, and CD300e) could be expressed on the surface of transfected COS-7 cells independently of the presence of the transmembrane adaptor polypeptides to which they associate, although the presence of those ITAM-bearing adaptors could enhance the levels of expression on the cell surface. Curiously, whereas co-transfection of CD300d and CD300c with FcϵRγ enhanced the surface expression of both receptors, co-transfection with DAP12 did not produce the same effect (Fig. 4C). By contrast, we have shown previously that the presence of DAP12 augmented the presence of CD300b on the surface of co-transfected COS-7 cells (9). These data strongly suggest that the interaction between ITAM-bearing adaptors and receptors is more complex than expected. In fact, immunoreceptors recruiting ITAM-bearing adaptors could be classified according to the structural elements involved in the establishment of the interaction (1). 1) The classical immunoreceptors bind to these adaptors through a mechanism of positive-negative charge complementation at the transmembrane level. This is the case for the receptors belonging to the KIR, ILT, and TREM families. 2) The non-classical immunoreceptors bind to the signaling adaptors independently of the presence of charged residues within the transmembrane domain of the receptors, although the presence of a negative charge in the adaptors seems to be important for the interaction. This second group includes integrins, growth factor receptors, and MHC proteins (1). We can include in this group those receptors bearing a negative charge within their transmembrane domain, such as CD300c (12), CD300d (Fig. 4E), and the IgE-binding α subunit (FcϵRα) (24). Interestingly, within the CD300 family, we find members binding the adaptor polypeptides both in a charge-dependent (CD300b and CD300e) and charge-independent (CD300c and CD300d) manner.

The lack of specific antibodies against CD300d makes difficult to define the location of this receptor in monocytes and granulocytes, which are positive for the receptor at the mRNA level. It is evident that the cellular compartmentalization would determine CD300d function. Our experiments show that CD300d is able to recruit the ITAM-bearing adaptor FcϵRγ, suggesting that if this receptor is able to reach the cell surface, it could deliver activating signals after engagement with a specific ligand similarly to CD300c (12). We have shown recently that CD300 molecules have the capability to interact with each other through their Ig domain. The combination of CD300 receptors in the cell surface complexes modulates differentially the signaling outcome in transfected cells (12), suggesting a new mechanism by which CD300 complexes could finely regulate the activation of myeloid cells upon interaction with their natural ligands. In this context, the CD300d ER confinement could serve to modify the extracellular expression of some CD300 receptors and, as a consequence, control the composition of CD300 surface complexes. Indeed, ER export has been shown to be a rate-limiting step for the cell surface transport of the receptors (32). This hypothesis has been validated both in COS-7 and RBL-2H3 cells, where CD300d reduced CD300f cell surface levels. Accordingly, CD300c membrane content was not modified by CD300d as consequence of the lack of interaction between these two receptors. In addition, although our co-transfection experiments have not induced the surface expression of CD300d in the presence of CD300f, we cannot discard the possibility that in real cells CD300d surface expression requires the formation of intracellular complexes with other CD300 molecules, such as CD300a, CD300b, or CD300e.

In summary, we have cloned and molecularly characterized CD300d, the sixth member of the human CD300 family of immunoreceptors. Our data suggest that CD300d, expressed exclusively in monocytes and granulocytes, could play a role in the regulation and/or formation of CD300 complexes on the cell surface and consequently modulate the state of activation of myeloid cells.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by Plan Nacional I+D Grant SAF2009-07548, Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias Grants PI080366 and PI1100045, and Agencia de Gestio d'Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca de Catalunya Grant 2009 SGR 493.

This article contains supplemental Table 1 and Fig. 1.

- ITAM

- immune receptor tyrosine-based activation motif

- PBMC

- peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- aa

- amino acid(s).

REFERENCES

- 1. Hamerman J. A., Ni M., Killebrew J. R., Chu C. L., Lowell C. A. (2009) The expanding roles of ITAM adapters FcRγ and DAP12 in myeloid cells. Immunol. Rev. 232, 42–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Long E. O. (2008) Negative signaling by inhibitory receptors. The NK cell paradigm. Immunol. Rev. 224, 70–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Veillette A., Latour S., Davidson D. (2002) Negative regulation of immunoreceptor signaling. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 20, 669–707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Speckman R. A., Wright Daw J. A., Helms C., Duan S., Cao L., Taillon-Miller P., Kwok P. Y., Menter A., Bowcock A. M. (2003) Novel immunoglobulin superfamily gene cluster, mapping to a region of human chromosome 17q25, linked to psoriasis susceptibility. Hum. Genet. 112, 34–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clark G. J., Ju X., Azlan M., Tate C., Ding Y., Hart D. N. (2009) The CD300 molecules regulate monocyte and dendritic cell functions. Immunobiology 214, 730–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cantoni C., Bottino C., Augugliaro R., Morelli L., Marcenaro E., Castriconi R., Vitale M., Pende D., Sivori S., Millo R., Biassoni R., Moretta L., Moretta A. (1999) Molecular and functional characterization of IRp60, a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily that functions as an inhibitory receptor in human NK cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 29, 3148–3159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Clark G. J., Green B. J., Hart D. N. (2000) The CMRF-35H gene structure predicts for an independently expressed member of an ITIM/ITAM pair of molecules localized to human chromosome 17. Tissue Antigens 55, 101–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Aguilar H., Alvarez-Errico D., García-Montero A. C., Orfao A., Sayós J., López-Botet M. (2004) Molecular characterization of a novel immune receptor restricted to the monocytic lineage. J. Immunol. 173, 6703–6711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Martínez-Barriocanal A., Sayós J. (2006) Molecular and functional characterization of CD300b, a new activating immunoglobulin receptor able to transduce signals through two different pathways. J. Immunol. 177, 2819–2830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Alvarez-Errico D., Sayós J., López-Botet M. (2007) The IREM-1 (CD300f) inhibitory receptor associates with the p85α subunit of phosphoinositide 3-kinase. J. Immunol. 178, 808–816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brckalo T., Calzetti F., Pérez-Cabezas B., Borràs F. E., Cassatella M. A., López-Botet M. (2010) Functional analysis of the CD300e receptor in human monocytes and myeloid dendritic cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 40, 722–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Martínez-Barriocanal A., Comas-Casellas E., Schwartz S., Jr., Martín M., Sayós J. (2010) CD300 heterocomplexes, a new and family-restricted mechanism for myeloid cell signaling regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 41781–41794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Alvarez-Errico D., Aguilar H., Kitzig F., Brckalo T., Sayós J., López-Botet M. (2004) IREM-1 is a novel inhibitory receptor expressed by myeloid cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 34, 3690–3701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Heit B., Colarusso P., Kubes P. (2005) Fundamentally different roles for LFA-1, Mac-1, and α4-integrin in neutrophil chemotaxis. J. Cell Sci. 118, 5205–5220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sayós J., Martín M., Chen A., Simarro M., Howie D., Morra M., Engel P., Terhorst C. (2001) Cell surface receptors Ly-9 and CD84 recruit the X-linked lymphoproliferative disease gene product SAP. Blood 97, 3867–3874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dereeper A., Guignon V., Blanc G., Audic S., Buffet S., Chevenet F., Dufayard J. F., Guindon S., Lefort V., Lescot M., Claverie J. M., Gascuel O. (2008) Phylogeny.fr. Robust phylogenetic analysis for the non-specialist. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, W465–W469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shnyder S. D., Hubbard M. J. (2002) ERp29 is a ubiquitous resident of the endoplasmic reticulum with a distinct role in secretory protein production. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 50, 557–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Umemoto E., Tanaka T., Kanda H., Jin S., Tohya K., Otani K., Matsutani T., Matsumoto M., Ebisuno Y., Jang M. H., Fukuda M., Hirata T., Miyasaka M. (2006) Nepmucin, a novel HEV sialomucin, mediates L-selectin-dependent lymphocyte rolling and promotes lymphocyte adhesion under flow. J. Exp. Med. 203, 1603–1614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Takatsu H., Hase K., Ohmae M., Ohshima S., Hashimoto K., Taniura N., Yamamoto A., Ohno H. (2006) CD300 antigen like family member G. A novel Ig receptor-like protein exclusively expressed on capillary endothelium. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 348, 183–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nufer O., Mitrovic S., Hauri H. P. (2003) Profile-based database scanning for animal L-type lectins and characterization of VIPL, a novel VIP36-like endoplasmic reticulum protein. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 15886–15896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Roth D., Lynes E., Riemer J., Hansen H. G., Althaus N., Simmen T., Ellgaard L. (2010) A diarginine motif contributes to the ER localization of the type I transmembrane ER oxidoreductase TMX4. Biochem. J. 425, 195–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Teasdale R. D., Jackson M. R. (1996) Signal-mediated sorting of membrane proteins between the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi apparatus. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 12, 27–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhang X., Dong C., Wu Q. J., Balch W. E., Wu G. (2011) Diacidic motifs in the membrane-distal C termini modulate the transport of angiotensin II receptors from the endoplasmic reticulum to the cell surface. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 20525–20535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rivera J., Fierro N. A., Olivera A., Suzuki R. (2008) New insights on mast cell activation via the high affinity receptor for IgE. Adv. Immunol. 98, 85–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kraft S., Kinet J. P. (2007) New developments in FcϵRI regulation, function, and inhibition. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 365–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Seminario M. C., Saini S. S., MacGlashan D. W., Jr., Bochner B. S. (1999) Intracellular expression and release of FcϵRI α by human eosinophils. J. Immunol. 162, 6893–6900 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hasegawa S., Pawankar R., Suzuki K., Nakahata T., Furukawa S., Okumura K., Ra C. (1999) Functional expression of the high affinity receptor for IgE (FcϵRI) in human platelets and its intracellular expression in human megakaryocytes. Blood 93, 2543–2551 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Platzer B., Fiebiger E. (2010) The signal peptide of the IgE receptor α-chain prevents surface expression of an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif-free receptor pool. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 15314–15323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Albrecht B., Woisetschläger M., Robertson M. W. (2000) Export of the high affinity IgE receptor from the endoplasmic reticulum depends on a glycosylation-mediated quality control mechanism. J. Immunol. 165, 5686–5694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lanier L. L., Corliss B., Wu J., Phillips J. H. (1998) Association of DAP12 with activating CD94/NKG2C NK cell receptors. Immunity 8, 693–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Smith K. M., Wu J., Bakker A. B., Phillips J. H., Lanier L. L. (1998) Ly-49D and Ly-49H associate with mouse DAP12 and form activating receptors. J. Immunol. 161, 7–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Petaja-Repo U. E., Hogue M., Laperriere A., Walker P., Bouvier M. (2000) Export from the endoplasmic reticulum represents the limiting step in the maturation and cell surface expression of the human δ-opioid receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 13727–13736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.