Background: An increase of apo- to holo-RBP4 concentration in plasma is observed in subjects with renal dysfunction and is supposed to induce cell damage.

Results: Increased apo-/holo-RBP4 ratio affects STRA6 signaling, which activates JAK2/STAT5 and then induces apoptosis.

Conclusion: Increased apo-RBP4 concentration can affect vitamin A signaling, leading to cell death.

Significance: This study establishes a direct relationship between increased apo-RBP4 concentration and apoptosis.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Cyclic AMP (cAMP), Jak Kinase, MAP Kinases (MAPKs), STAT Transcription Factor, Cellular Retinol-binding Protein (CRBP), Retinol-binding Protein 4 (RBP4), Stimulated by Retinoic Acid 6 (STRA6), p38

Abstract

The increase of apo-/holo-retinol-binding protein 4 (RBP4) concentrations has been found in subjects with renal dysfunction and even in diabetic patients with microalbuminuria. Holo-RBP4 is recognized to possess cytoprotective function. Therefore, we supposed that the relative increase in apo-RBP4 might induce cell damage. In this study, we investigated the signal transduction that activated apoptosis in response to the increase of apo-/holo-RBP4 concentration. We found that increase of apo-/holo-RBP4 concentration ratio delayed the displacement of RBP4 with “stimulated by retinoic acid 6” (STRA6), enhanced Janus kinase 2 (JAK2)/STAT5 cascade, up-regulated adenylate cyclase 6 (AC6), increased cAMP, enhanced JNK1/p38 cascade, suppressed CRBP-I/RARα (cellular retinol-binding protein/retinoic acid receptor α) expression, and led to apoptosis in HK-2 and human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Furthermore, STRA6, JAK2, STAT5, JNK1, or p38 siRNA and cAMP-PKA inhibitor reversed the repression of CRBP-I/RARα and apoptosis in apo-RBP4 stimulation. In conclusion, this study indicates that the increase of apo-/holo-RBP4 concentration may influence STRA6 signaling, finally causing apoptosis.

Introduction

Retinol-binding protein 4 (RBP4;2 molecular mass ∼21 kDa) is mainly synthesized in the liver and white adipose tissues, where it binds to retinol and then is secreted into circulation (1, 2). RBP4 has an important role in regulating vitamin A metabolism and maintaining a constant and continuous supply of vitamin A to peripheral tissues for a variety of physiological processes. Under physiological conditions, 90% of blood RBP4 is holo-RBP4 (bound to retinol), and 10% (unbound to retinol) circulates as apo-RBP4, which is retinol-free (3, 4). After releasing retinol, the remaining apo-RBP4 is easily filtered through glomeruli and subsequently reabsorbed and catabolized in the proximal tubules (5). Therefore, renal functional impairment is known to interfere with RBP4 homeostasis through its influence on RBP4 catabolism (3, 4). Frey et al. (6) found that the relative amount of apo-/holo-RBP4 in chronic kidney disease patients was 32.5/67.5%, whereas the relative amount in control subjects was 13.6/86.4%. Recently, several studies have reported that RBP4 is elevated in serum of subjects with diabetes and even with impaired glucose tolerance (7–9). The elevation of serum RBP4 in type 2 diabetic patients has recently been demonstrated to be the result of renal dysfunction, even in the microalbuminuria stage (10–15). According to these results, it is reasonable to presume that the elevation of relative amounts between apo-RBP4 and holo-RBP4 in subjects with chronic kidney disease may aggravate cell damage.

STRA6 (stimulated by retinoic acid 6), as a specific membrane receptor for RBP4, mediates cellular retinol uptake from holo-RBP4 (16, 17). Within cells, retinoids must be bound to cellular retinol-binding proteins (CRBPs) or cellular retinoic acid-binding proteins and produce effects via activating retinoic acid receptors (RARs) and retinoid X receptors (18). In addition, RBP4 binding to STRA6 can activate STAT5 (signal transducers and activator of transcription 5)/JAK2 (Janus kinase) cascade to inhibit insulin responses (19). This means that RBP4 is not only a carrier of retinol, but also a cytokine in circulation. Until now, whether apo-RBP4 may bind STRA6 and affect retinoid signaling has not been investigated.

Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) are common intracellular signaling networks in responses to various cytokines and stress (20, 21). The cAMP-stimulated MAPK pathway also activates apoptosis, inflammation, and fibrosis in kidney (21). The activation of MAPK pathway has also been observed in injury of vascular cells (20). Especially, the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38 in MAPK family members are known to be involved in the regulation of apoptosis (20, 21). Interestingly, JNK and p38 activation are also reported to repress RARs expression leading to apoptosis (22). Furthermore, JAK/STAT pathway commonly affects JNK/p38 cascades in several cell types (23–25). Therefore, we sought to investigate whether the increase of apo-/holo-RBP4 concentration can repress CRBP-I/RARα leading to apoptosis through JAK2/STAT5-activated cAMP/JNK1/p38 pathway in human renal proximal tubular cells (HK-2) and human umbilical vein endothelial cells.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Primary antibodies for Western blot analysis were as follows: mouse monoclonal anti-human STRA6 antibody (R&D Systems), goat polyclonal anti-human antibody (Abcam), rabbit polyclonal anti-JAK2 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), rabbit polyclonal anti-STAT5 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit polyclonal anti-caspase3 antibody, active form (CPP32) (BD Biosciences), mouse monoclonal GAPDH antibody (Millipore), goat polyclonal anti-human CRBP-I antibody (Abcam), rabbit polyclonal anti-RARα antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit polyclonal anti-JNK1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse monoclonal anti-p-JNK1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit polyclonal anti-p38 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse monoclonal anti-p-p38 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and rabbit polyclonal anti-adenylate cyclase 6, AC6 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Secondary antibodies for Western blot analysis such as goat-anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody and goat-anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Donkey-anti-goat horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody was purchased from Abcam. The inhibitor of cAMP-dependent protein kinase A, Rp-cAMPS, was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Cell Culture

HK-2 cells (human renal proximal tubular epithelial cells) were cultured in keratinocyte-serum free medium (Invitrogen) with 5 ng/ml recombinant epidermal growth factor and 40 μg/ml bovine pituitary extract supplemented with 100 units/ml penicillin (Invitrogen) and 100 mg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen) and harvested with the medium and then kept in a humidified incubator at 37 °C under 95% air and 5% CO2. HUVEC (human umbilical vein endothelial cells) were cultured in RPMI medium 1640 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% calf serum (Invitrogen), 100 units/ml penicillin (Invitrogen), and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen) and harvested with the medium and then kept in a humidified incubator at 37 °C under 95% air and 5% CO2.

All-trans-retinoic Acid Binding to Apo-RBP4

The method of retinoic acid loading to apo-RBP4 has been performed previously (26). 2 mg/ml human apo-RBP4 (Sigma) was incubated with 1 mm all-trans-retinoic acid (Sigma) in ethanol containing 10% glycerol (26). Holo-RBP4 was purified by using a Corning Spin-X UF filter tube (Corning). The holo-RBP4 concentration was measured by a human RBP4 ELISA kit (R&D Systems). Holo-RBP4 was identified by using nondenaturating PAGE-immunoblotting (6).

RBP4 Binding Assay

The RBP4 binding assay has been performed previously (17). Fluorescence compound was labeled to RBP4 with fluorescein labeling kit-NH2 (Kamiya). Cells were incubated with fluorescence-labeled RBP4 in medium at 37 °C. After washing unbound fluorescence-labeled RBP4 three times with PBS, membrane proteins were extracted by the Mem-PER eukaryotic membrane protein extraction reagent kit (Thermo Fisher). Membrane protein extracts were transferred to a 96-well plate for reading fluorescence intensity. Each experiment was repeated at least six times throughout the study.

Western Blot

Cells were washed with PBS, and then total protein was extracted with M-PER mammalian protein extraction reagent (Thermo Fisher). The protein of samples was separated with SDS-PAGE. The separated proteins on SDS-PAGE were transferred onto PVDF membrane (Amersham Biosciences) with electrophoresis. Then, the PVDF membrane was blocked with Tris-buffered saline with 0.2% Tween 20 (TBS-T) containing 5% skim milk at 4 °C for overnight. To detect protein expression, the PVDF membrane was incubated with diluted primary antibodies in TBS-T containing 5% skim milk. After washing the membrane with TBS-T, the PVDF membrane was incubated with a 1:10000 dilution of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody in TBS-T containing 5% skim milk. Western blots were detected by an ECL detection kit (Millipore) to induce the chemiluminescence signal, which was captured on x-ray film.

Real-time Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from TRIzol (Invitrogen) and converted to cDNA with a SuperScript III cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cDNA amplification was quantified by incorporation with SYBR Green I quantitative PCR master mix (OriGene Technologies, Inc.) into double-stranded DNA according to manufacturer's instructions. The primers target human GAPDH, STRA6, CRBP-I, RARα, and AC6 mRNA purchased from OriGene Technologies. Data analysis was performed by the formula -Foldchange = 2(ΔCttreatment − ΔCt control).

Small Interfering RNA and siRNA Transfection

We purchased siRNA targeting human STRA6, STAT5, JAK2, JNK1, and p38 mRNA and a nontargeting control siRNA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Cells were seeded in 12-well plates at a density of 2 × 105cells/well in 2 ml of antibiotic-free medium and were then cultured cell under 37 °C and 5% CO2 until the cell growth covered 80% of the area of the dish. After maintaining incubation overnight, siRNA was mixed into transfection reagent and transfection medium (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and the mixture was added into cells and cultured for 7 h. Then, we replaced fresh medium and incubated cells for 24 h and proceeded with treatment. A negative control scramble siRNA provided by the manufacturer (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) did not reduce STRA6, STAT5, JAK2, JNK1, and p38 protein expression.

Immunoprecipitation of RBP4-STRA6 Complex

RBP4-STRA6 complex was immunoprecipitated by STRA6 monoclonal antibody with protein G plus/protein A-agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). STRA6-immunoprecipitated precipitates were blotted for anti-RBP4 antibody (R&D Systems).

Terminal Transferase-mediated Deoxyuridine Triphosphate Nick End-labeling (TUNEL) Assay

Cells were plated in eight-chamber glass slides. TUNEL analysis was for in situ detection of apoptotic cells. Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and then analyzed using an ApopTag in situ apoptosis detection kit (Chemicon). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Lonza Walkersville).

Transfection of Plasmid Containing CRBP-I cDNA

The pCMV6-GFP vector and human CRBP-I cDNA (GenBankTM number NM_002899) was purchased from OriGene Technologies. The CRBP cDNA was inserted into the SgfI/MluI site of the phCMV6-GFP expression vector plasmid (OriGene Technologies). Cells were transfected by using pCMV6-CRBP-I-GFP or pCMV6-GFP vector with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Cells were incubated in Opti-MEM (Invitrogen) at 37 °C for 5 h and then placed in freshly changed culture medium for experiments.

Enzyme-linked Immunoassay of cAMP

Concentrations of cAMP were measured by an enzyme-linked immunoassay (Cayman). The cells were grown in 24-well plates and stimulated with RBP4. Cell lysates were collected at 24 h for cAMP detection. Each experiment was repeated at least six times throughout the study.

Statistical Analysis

Data obtained from this study were expressed as the mean ± S.D. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 3.0 (GraphPad Software). Differences were assessed by one-way analysis of variance and Bonferroni's test. p values < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Increased Ratio of Apo- to Holo-RBP4 Concentration Enhanced RBP4 Binding with STRA6, Phosphorylation of STAT5/JAK2, Active Caspase 3, and Apoptosis in HK-2 and HUVEC Cells

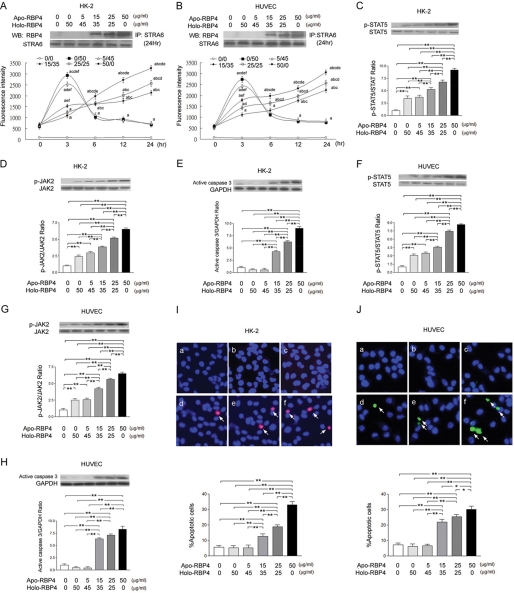

The RBP4 binding assay demonstrated an increase in RBP4 binding activity after stimulation with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 0:50 and 5:45 (μg/ml:μg/ml) as compared with the stimulation with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 0:0, 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 (μg/ml:μg/ml) in HK-2 (Fig. 1A) and HUVEC (Fig. 1B) at 3 h. However, at 24 h, the immunoprecipitation and RBP4 binding assay demonstrated an increase in RBP4 binding activity after stimulation with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 (μg/ml:μg/ml) as compared with the stimulation with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 0:0, 0:50, and 5:45 (μg/ml:μg/ml) in HK-2 (Fig. 1A) and HUVEC (Fig. 1B). In HK-2 cells, the Western blot analysis demonstrated significant increase in STAT5 (Fig. 1C) and JAK2 (Fig. 1D) phosphorylation and active caspase 3 expression (Fig. 1E) after stimulation with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 (μg/ml:μg/ml) as compared with the stimulation with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 0:0, 0:50, and 5:45 (μg/ml:μg/ml). In HUVEC cells, the Western blot analysis also demonstrated a significant increase in STAT5 (Fig. 1F) and JAK2 (Fig. 1G) phosphorylation and active caspase 3 expression (Fig. 1H) after stimulation with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 (μg/ml:μg/ml) as compared with the stimulation with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 0:0, 0:50, and 5:45 (μg/ml:μg/ml). The TUNEL assay demonstrated an increased percentage of apoptotic cells in HK-2 (Fig. 1I) and HUVEC (Fig. 1J) cells treated with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 (μg/ml:μg/ml) as compared with the stimulation withapo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 0:0, 0:50, and 5:45 (μg/ml:μg/ml).

FIGURE 1.

Increased ratio of apo- to holo-RBP4 concentration enhanced binding between RBP4 and STRA6, phosphorylation of STAT5 and JAK2, and apoptosis in HK-2 and HUVEC cells. HK-2 and HUVEC cells were stimulated with 0:0, 0:50, 5:45, 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture (μg/ml:μg/ml). A and B, RBP4 binding assay and immunoprecipitation/immunoblots (WB) demonstrated STRA6-immunoprecipitated precipitates blotted with anti-RBP4 antibody in HK-2 (A) and HUVEC (B) cells. C–E, in HK-2 cells, the increased densities of p-STAT5 (C), the increased densities of p-JAK2 (D), and the increased densities of active caspase 3 (E) were demonstrated. F–H, in HUVEC cells, the increased densities of p-STAT5 (F), the increased densities of p-JAK2 (G), and the increased densities of active caspase 3 (H) were demonstrated. I and J, apoptotic cells of HK-2 (I) and HUVEC cells (J) (indicated by arrow) were detected with TUNEL assay in treatment of 0:0 (panel a), 0:50 (panel b), 5:45 (panel c), 15:35 (panel d), 25:25 (panel e), and 50:0 (panel f) apo-RBP4 (μg/ml):holo-RBP4 (μg/ml) mixture. The percentages of positive cells were calculated in eight random areas (magnification ×200). Each point represents mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments performed in triplicate; a, p < 0.01 versus 0:0; b, p < 0.01 versus 0:50; c, p < 0.01 versus 5:45, d, p < 0.01 versus 15:35; e, p < 0.01 versus 25:25; f, p < 0.01 versus 50:0; **, p < 0.01.

Increased Ratio of Apo- to Holo-RBP4 Concentration Activated Phosphorylation of JNK1 and p38 in HK-2 and HUVEC Cells

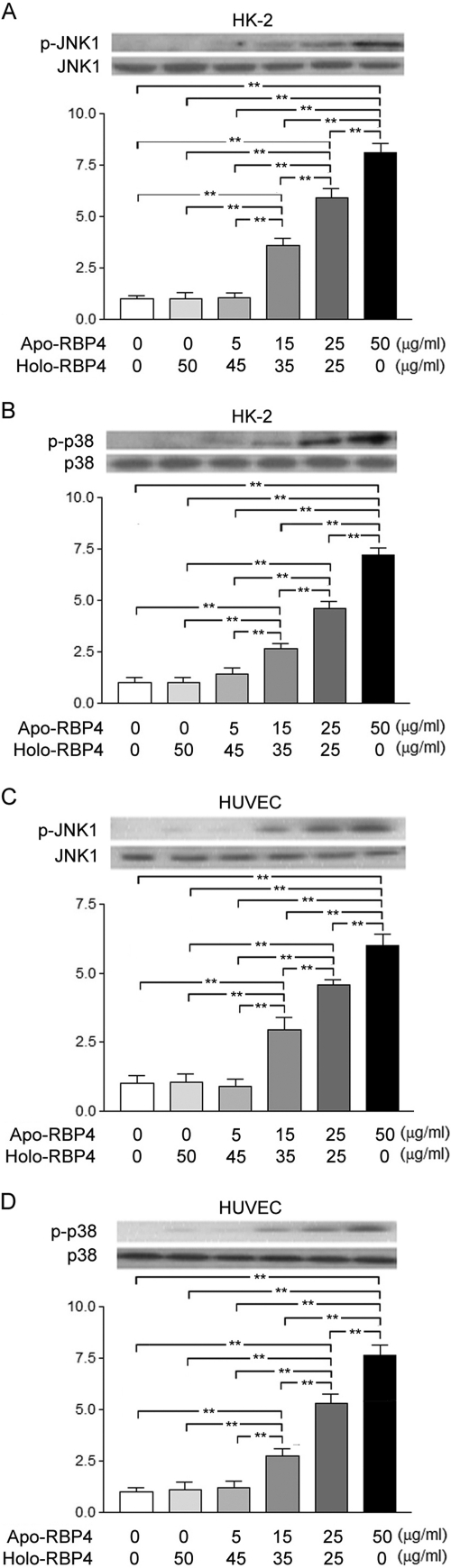

In HK-2 cells, the Western blot analysis demonstrated a significant increase of JNK1 (Fig. 2A) and p38 (Fig. 2B) phosphorylation after stimulation with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 (μg/ml:μg/ml) as compared with the stimulation with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 0:0, 0:50, and 5:45 (μg/ml:μg/ml). In HUVEC cells, the Western blot analysis demonstrated a significant increase of JNK1 (Fig. 2C) and p38 (Fig. 2D) phosphorylation after stimulation with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 (μg/ml:μg/ml) as compared with the stimulation with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 0:0, 0:50, and 5:45 (μg/ml:μg/ml).

FIGURE 2.

Increased ratio of apo- to holo-RBP4 concentration enhanced JNK1 and p38 phosphorylation in HK-2 and HUVEC cells. HK-2 and HUVEC cells were stimulated with 0:0, 0:50, 5:45, 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture (μg/ml:μg/ml). A and B, in HK-2 cells, the increased densities of p-JNK1 (A) and the increased densities of p-p38 (B) were demonstrated. C and D, in HUVEC cells, the increased densities of p-JNK1 (C) and the increased densities of p-p38 (D) were demonstrated. Each point represents mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments performed in triplicate; **, p < 0.01.

Increased Ratio of Apo- to Holo-RBP4 Concentration Enhanced STAR6 Expression but Suppressed CRBP-I and RARα Expression in HK-2 and HUVEC Cells

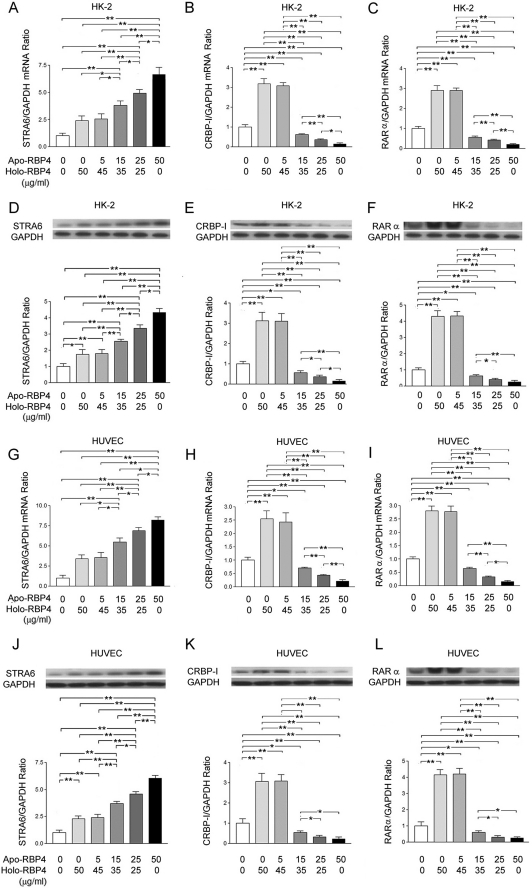

In HK-2 cells, the quantitative RT-PCR analysis showed a significant increase in the expression of STRA6 mRNA (Fig. 3A) and the suppressed expression of CRBP-I (Fig. 3B) and RARα (Fig. 3C) mRNA after stimulation with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 (μg/ml:μg/ml) as compared with the stimulation with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 0:0, 0:50, and 5:45 (μg/ml:μg/ml). The Western blot analysis also demonstrated a significant increase in the STRA6 expression (Fig. 3D) and the suppressed expression of CRBP-I (Fig. 3E) and RARα (Fig. 3F) after stimulation with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 (μg/ml:μg/ml) as compared with the stimulation with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 0:0, 0:50, and 5:45 (μg/ml:μg/ml). In HUVEC cells, the quantitative RT-PCR analysis showed a significant increase in the expression of STRA6 mRNA (Fig. 3G) and the suppressed expression of CRBP-I (Fig. 3H) and RARα (Fig. 3I) mRNA after stimulation with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 (μg/ml:μg/ml) as compared with the stimulation with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 0:0, 0:50, and 5:45 (μg/ml:μg/ml). The Western blot analysis also demonstrated a significant increase in STRA6 expression (Fig. 3J) and the suppressed expression of CRBP-I (Fig. 3K) and RARα (Fig. 3L) after stimulation with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 (μg/ml) as compared with the stimulation with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 0:0, 0:50, and 5:45 (μg/ml:μg/ml).

FIGURE 3.

Increased ratio of apo- to holo-RBP4 concentration induced STRA6 expression and depressed expression of CRBP-I and RARα. HK-2 and HUVEC cells were stimulated with 0:0, 0:50, 5:45, 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture (μg/ml:μg/ml). A–F, results in HK-2 cells. A, the mRNA levels of STRA6 were normalized with GAPDH control. B, the mRNA levels of CRBP-I were normalized with GAPDH control. C, the mRNA levels of RARα were normalized with GAPDH control. D, the relative densities of STRA6 were normalized with GAPDH control, E, the relative densities of CRBP-I were normalized with GAPDH control. F, the densities of RARα were normalized with GAPDH control. G–L, results in HUVEC cells. G, the mRNA levels of STRA6 were normalized with GAPDH control. H, the mRNA levels of CRBP-I were normalized with GAPDH control. I, the mRNA levels of RARα were normalized with GAPDH control. J, the relative densities of STRA6 were normalized with GAPDH control. K, the relative densities of CRBP-I were normalized with GAPDH control. L, the relative densities of RARα were normalized with GAPDH control. Each point represents mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments performed in triplicate; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

Increased Ratio of Apo- to Holo-RBP4 Concentration Induced cAMP via STRA6, STAT5, and JAK2 Action

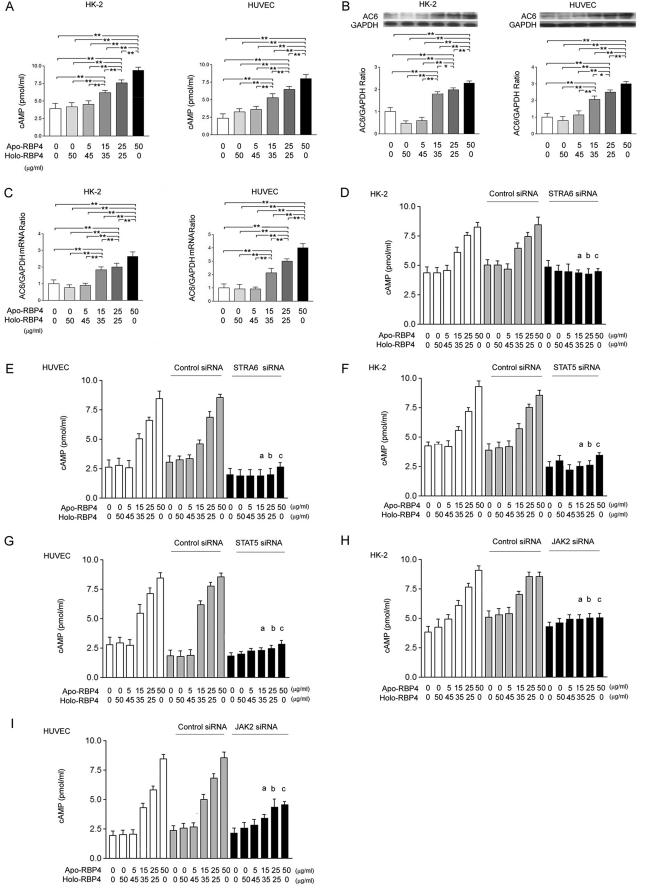

In HK-2 and HUVEC cells, the Western blot analysis demonstrated a significant increase in cAMP (Fig. 4A), adenylate cyclase 6, AC6 (Fig. 4B), and AC6 mRNA (Fig. 4C) expression after stimulation with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 (μg/ml:μg/ml) as compared with the stimulation of the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 0:0, 0:50, and 5:45 (μg/ml:μg/ml). We transfected STRA6, STAT5, or JAK2 siRNA into HK-2 and HUVEC cells, and then we stimulated cells with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 0:0, 5:45, 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 (μg/ml:μg/ml). The enzyme immunoassay demonstrated that the significant increases of cAMP were attenuated by STRA6 siRNA in HK-2 (Fig. 4D) and HUVEC (Fig. 4E) cells treated with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 (μg/ml:μg/ml). In STAT5 siRNA (Fig. 4F and 4G)-transfected and JAK2 siRNA (Fig. 4, H and I)-transfected HK-2 and HUVEC cells, the significant increase of cAMP was also significantly attenuated after stimulation with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 (μg/ml:μg/ml).

FIGURE 4.

Increased ratio of apo- to holo-RBP4 concentration induced cAMP via STRA6, STAT5, and JAK2 action. HK-2 and HUVEC cells were stimulated with 0:0, 0:50, 5:45, 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 apo-/holo-RBP4 mixtures (μg/ml:μg/ml) for 24 h. A, the cAMP concentrations were assayed by enzyme immunoassay. B, the relative densities of AC6 were normalized with GAPDH control. C, the mRNA levels of AC6 were normalized with GAPDH control. After siRNA or control siRNA transfection for 48 h, HK-2 and HUVEC cells were stimulated with 0:0, 0:50, 5:45, 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 apo-/holo-RBP4 mixtures (μg/ml:μg/ml) for 24 h. D–I, in STRA6 (D and E), STAT5 (F and G), and JAK2 (H and I) siRNA-transfected cells, the increased cAMP concentrations were reversed. Each point represents mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments performed in triplicate; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; a, p < 0.01 versus 15:35 in control and control siRNA group; b, p < 0.01 versus 25:25 in control and control siRNA group; c, p < 0.01 versus 50:0 in control and control siRNA group.

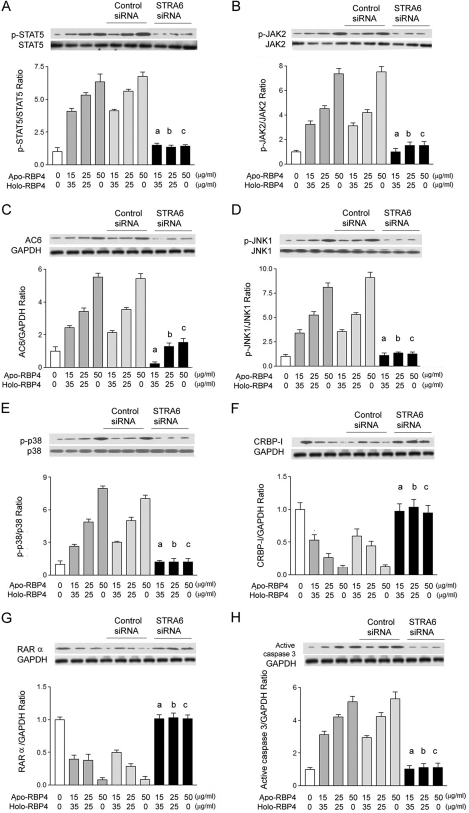

STRA6 siRNA Reversed Effects of Increased Apo- to Holo-RBP4 Concentration Ratio

We transfected STRA6 siRNA into HK-2 cells and then stimulated cells with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 0:0, 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 (μg/ml:μg/ml). The Western blot analysis demonstrated that STRA6 siRNA attenuated the phosphorylation of STAT5 (Fig. 5A) and JAK2 (Fig. 5B), AC6 expression (Fig. 5C), the phosphorylation of JNK1 (Fig. 5D) and p38 (Fig. 5E), the suppressed expression of CRBP-I (Fig. 5F) and RARα (Fig. 5G), and the expression of active caspase 3 (Fig. 5H) in HK-2 cells treated with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 (μg/ml:μg/ml).

FIGURE 5.

STRA6 siRNA reversed the increased ratio of apo- to holo-RBP4 concentration-induced effects. After STRA6 siRNA or control siRNA transfection for 48 h, HK-2 cells were stimulated with 0:0, 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 apo-/holo-RBP4 mixtures (μg/ml:μg/ml) for 24 h. A, the increased densities of p-STAT5 were reversed by STRA6 siRNA. B, the increased densities of p-JAK2 were reversed by STRA6 siRNA. C, the increased densities of AC6 were reversed by STRA6 siRNA. D, the increased densities of p-JNK1 were reversed by STRA6 siRNA. E, the increased densities of p-p38 were reversed by STRA6 siRNA. F, the decreased densities of CRBP-I were reversed by STRA6 siRNA. G, the decreased densities of RARα were reversed by STRA6 siRNA. H, the increased densities of active caspase 3 were reversed. Each point represents mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments performed in triplicate; a, p < 0.01 versus 15:35 in control and control siRNA group; b, p < 0.01 versus 25:25 in control and control siRNA group; c, p < 0.01 versus 50:0 in control and control siRNA group.

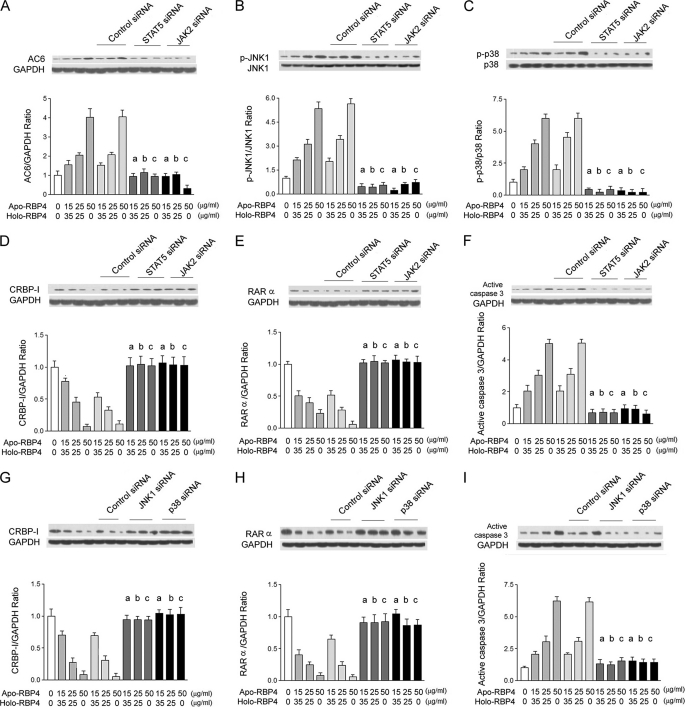

STAT5, JAK2, JNK1, or p38 siRNA Reversed Effects of Increased Apo- to Holo-RBP4 Concentration Ratio

We transfected STAT5 or JAK2 siRNA into HK-2 cells and then stimulated cells with the addition of apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 0:0, 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 (μg/ml:μg/ml). The Western blot analysis demonstrated that STAT5 or JAK2 siRNA significantly attenuated AC6 expression (Fig. 6A), phosphorylation of JNK1 (Fig. 6B) and p38 (Fig. 6C), the suppressed expression of CRBP-I (Fig. 6D) and RARα (Fig. 6E), and the expression of active caspase 3 (Fig. 6F) in HK-2 cells treated with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 (μg/ml:μg/ml). Furthermore, we transfected JNK1 or p38 siRNA into HK-2 cells and then stimulated cells with the addition of apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 0:0, 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 (μg/ml:μg/ml). The Western blot analysis demonstrated that JNK1 or p38 siRNA also significantly attenuated the suppressed expression of CRBP-I (Fig. 6G) and RARα (Fig. 6H) and the expression of active caspase 3 (Fig. 6I) in HK-2 cells treated with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 (μg/ml:μg/ml).

FIGURE 6.

STAT5, JAK2, JNK1, or p38 siRNA reversed the increased ratio of apo- to holo-RBP4 concentration-induced effects. After STAT5 siRNA, JAK2 siRNA, JNK1, p38 siRNA, or control siRNA transfection for 48 h, HK-2 cells were stimulated with 0:0, 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 apo-/holo-RBP4 mixtures (μg/ml:μg/ml) for 24 h. A–F, results in STAT5 or JAK2 siRNA-transfected HK-2 cells. A, the increased densities of AC6 were reversed. B, the increased densities of p-JNK1 were reversed. C, the increased densities of p-p38 were reversed. D, the decreased densities of CRBP-I were reversed. E, the decreased densities of RARα were reversed. F, the increased densities of active caspase 3 were reversed by STAT5 and JAK2 siRNA. G–I, results in JNK1- or p38 siRNA-transfected HK-2 cells. G, the decreased densities of CRBP-I were reversed. H, the decreased densities of RARα were reversed. I, the increased densities of active caspase 3 were reversed with GAPDH control. Each point represents mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments performed in triplicate; a, p < 0.01 versus 15:35 in control and control siRNA group; b, p < 0.01 versus 25:25 in control and control siRNA group; c, p < 0.01 versus 50:0 in control and control siRNA group.

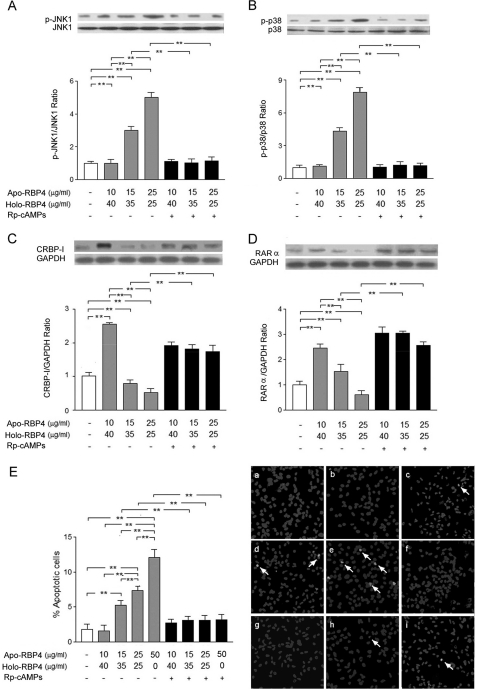

Effects of Increased Apo- to Holo-RBP4 Concentration Ratio Were Reversed by Rp-cAMPS

We incubated HK-2 cells after stimulation with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 0:0, 10:40, 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 (μg/ml:μg/ml) with or without Rp-cAMPS (0.5 μm) for 24 h. The Western blot analysis demonstrated that Rp-cAMPS significantly attenuated the JNK1 (Fig. 7A) and p38 (Fig. 7B) phosphorylation and suppressed expression of CRBP-I (Fig. 7C) and RARα (Fig. 7D) in HK-2 cells treated with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 (μg/ml:μg/ml). TUNEL assay also demonstrated that Rp-cAMPS significantly attenuated apoptosis in HK-2 cells treated with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 (μg/ml:μg/ml) (Fig. 7E).

FIGURE 7.

Rp-cAMPS attenuated the increased ratio of apo- to holo-RBP4 concentration-induced effects. HK-2 cells were incubated in medium containing 0:0, 10:40, 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 apo-/holo-RBP4 mixtures (μg/ml:μg/ml) with or without Rp-cAMPS for 24 h. A, the increased densities of p-JNK1 were reversed by Rp-cAMPS. B, the increased densities of p-p38 were reversed by Rp-cAMPS. C, the decreased densities of CRBP-I were reversed by Rp-cAMPS. D, the decreased densities of RARα were reversed by Rp-cAMPS. E, apoptotic cells were detected with TUNEL assay in the treatment of apo-/holo-RBP4 mixtures at 0:0 (panel a), 10:40 (panel b), 15:35 (panel c), 25:25 (panel d), 50:0 (panel e), and 10:40 with 0.5 μm Rp-cAMPS (panel f); 15:35 with 0.5 μm Rp-cAMPS (panel g); 25:25 with 0.5 μm Rp-cAMPS (panel h); and 50:0 with 0.5 μm Rp-cAMPS (panel i). The percentages of positive cells were calculated in eight random areas (magnification ×200). Each point represents mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments performed in triplicate; **, p < 0.01.

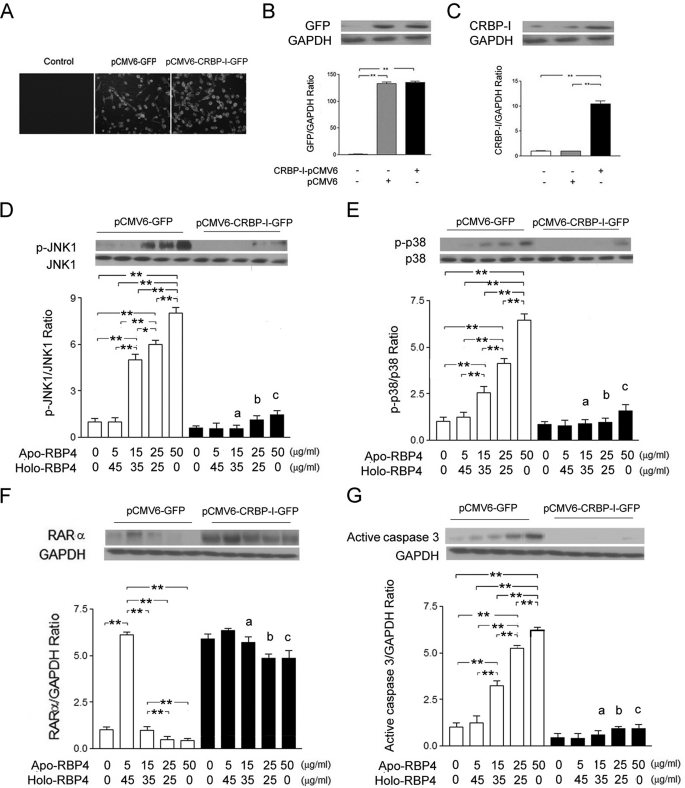

Transfection of CRBP-I cDNA Significantly Reversed Activation of JNK1 and p38 Phosphorylation and Suppressed Expression of RARα in HK-2 Cells Treated with Increase of Apo-/Holo-RBP4 Concentration

We transfected plasmid containing human CRBP-I cDNA into HK-2 cells to up-regulate CRBP-I and then stimulated cells with the addition of apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 0:0, 5:45, 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 (μg/ml:μg/ml). The green fluorescence (GFP expression) was observed in pCMV6-GFP and pCMV6-CRBP-I-GFP vector-transfected HK-2 cells (Fig. 8A). The GFP protein was also highly expressed in pCMV6-GFP and pCMV6-CRBP-I-GFP vector-transfected HK-2 cells (Fig. 8B). The significant expression of CRBP-I was detected in pCMV6-CRBP-I-GFP vector-transfected HK-2 cells (Fig. 8C). Western blot assay demonstrated that the phosphorylation of JNK1 (Fig. 8D) and p38 (Fig. 8E), the suppressed expression of RARα (Fig. 8F), and the expression of active caspase 3 (Fig. 8G) were significantly reversed in pCMV6-CRBP-I-GFP vector-transfected cells treated with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 (μg/ml:μg/ml).

FIGURE 8.

CRBP-I cDNA transfection reversed the increased ratio of apo- to holo-RBP4 concentration-induced effects. HK-2 cells were transfected for 24 h with plasmids, pCMV6-GFP, or pCMV6-CRBP1-GFP. After transfection, HK-2 cells were incubated in medium with 0:0, 5:45, 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 apo-/holo-RBP4 mixtures (μg/ml:μg/ml) for 24 h. A, GFP fluorescence expression was observed in fluorescence microscopy (magnification ×200). B, the relative densities of GFP were normalized with GAPDH control. C, the relative densities of CRBP-I were normalized with GAPDH control. D, the increased densities of p-JNK were reversed by CRBP-I cDNA transfection. E, the increased densities of p-p38 were reversed by CRBP-I gene transfection. F, the decreased densities of RARα were reversed by CRBP-I cDNA transfection. G, the increased densities of active caspase 3 were reversed. Each point represents mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments performed in triplicate; a, p < 0.01 versus 15:35 in pCMV6-GFP group; b, p < 0.01 versus 25:25 in pCMV6-GFP group; c, p < 0.01 versus 50:0 in pCMV6-GFP group; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

This study indicates that the increase of apo-RBP4/holo-RBP4 concentration may influence the binding of RBP4 on STRA6, enhance JAK2 and STAT5 phosphorylation, and then increase AC6-catalyzed cAMP production, which leads to apoptosis through suppression of CRBP-I and RARα and activation of JNK1 and p38. The kidneys play an important role in the homeostasis of RBP4 in physiological conditions and in renal dysfunction. Several studies have shown that serum RBP4 concentration increases in subjects with elevated serum creatinine or urine albumin excretion (10). Some of these studies showed that the elevation of RBP4 mainly comes from the increase of apo-RBP4 (6, 27). Frey et al. (6) found that the relative amount of apo-/holo-RBP4 in patients with increased creatinine level was 32.5/67.0%, whereas the relative amount in control subjects was 13.6/86.4%. In this study, we demonstrated that RBP4, composed of 15 μg/ml apo-RBP4 and 35 μg/ml holo-RBP4, can activate caspase 3 activity and increase apoptotic cell numbers in HK-2 cells and endothelial cells. The induction of apoptosis is aggravated by increasing the molar ratio of apo-/holo-RBP4. Moreover, this study also showed that the increased percentage of apo-RBP4 in total RBP4 can activate phosphorylation of JNK and p38. By interfering with JNK and p38, siRNA can attenuate the activation of apoptosis by increasing the apo-RBP4/holo-RBP4 concentration ratio in HK-2 cells. Apoptosis is one important pathway to induce kidney disease through activation of JNK and p38 MAPK phosphorylation (21). To our knowledge, this study is the first to demonstrate that the increase of relative concentration between apo-RBP4 and holo-RBP4 concentrations can activate apoptosis through JNK1 and p38 signal pathways in kidney cells.

STRA6 is expressed in various organs, especially in eye, brain, and kidney (28). Kawaguchi et al. (17) confirmed that the RBP4/STRA6/CRBP-1/RARα system transports retinol by involving an extracellular carrier protein but not depending on endocytosis. Additionally, apo-RBP observed a certain affinity with its receptor (29, 30). In our study, at 3 h, the binding activity of RBP4 with STAR6 in HK2 and HUVEC cells treated with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 0:50 and 5:45 (μg/ml:μg/ml) was remarkably higher than cells treated with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 (μg/ml:μg/ml). However, the binding activity of RBP4 with STAR6 decreased to the baseline level at 6, 12, and 24 h in cells treated with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 0:50 and 5:45 (μg/ml:μg/ml), whereas binding activity was increased at higher levels in cells treated with the apo-/holo-RBP4 mixture at 15:35, 25:25, and 50:0 (μg/ml:μg/ml). Moreover, the increased apo-/holo-RBP4 ratio also enhanced expression of RBP4-STRA6 complex with immunoprecipitation at 24 h. Meanwhile, the increase of apo-/holo-RBP4 ratio increased STRA6 expression and decreased CRBP-1 and RARα expression at 24 h. These results suggest that apo-RBP4 might tightly bind to STAR6 with less retinol delivery, whereas holo-RBP4 did not occupy STRA6 after retinol uptake. Therefore, the delayed displacement of apo-RBP4 with STRA6 may induce STRA6 expression, but may influence vitamin A uptake and retinoic acid-regulating genes by suppressing CRBP-I and RARα. Furthermore, our study showed that STRA6 siRNA not only reversed the decrease of CRBP-1 and RARα, but also attenuated the increase of JNK1 and p38 phosphorylation, active caspase 3, and apoptotic cell number after stimulation by increased apo-/holo-RBP4 concentration ratio.

More recently, it was shown that the binding of holo-RBP4 to STRA6 can induce STRA6 phosphorylation and leads to activation of JAK2/STAT5 signaling cascade (19). In the present study, the increase of apo-/holo-RBP4 concentration ratio increases STRA6 expression and concurrently activates JAK2 and STAT5 phosphorylation in HK-2 and HUVEC cells. We also found that STRA6 siRNA can reduce the increased phosphorylation of JAK2/STAT5 activated by the increase of apo/holo-RBP4 ratio. Similar to STRA6 siRNA, JAK2 and STAT5 siRNA can also reverse the decrease of CRBP-1 and RARα, attenuate the increase of JNK/p38 MAPK phosphorylation, and activate caspase 3 after stimulation by increased apo-/holo-RBP4 concentration ratio. These results suggest that an increase of apo-/holo-RBP4 concentration ratio can activate JAK2/STAT5 signaling cascade leading to apoptosis via increasing STRA6 phosphorylation.

cAMP, an important proapoptotic factor, can regulate a variety of intracellular signaling pathways involved in the development and progression of renal and vascular diseases (24, 31, 32). In this study, the increase of apo-/holo-RBP4 concentration ratio increased AC6 expression, cAMP concentration, JNK1/p38 phosphorylation, and apoptosis in HK-2 and HUVEC cells. The blockade of STRA6, JAK2, and STAT5 by siRNA can significantly attenuate the above changes induced by the increased concentration ratio of apo- to holo-RBP4. Furthermore, the inhibition of PKA activity by Rp-cAMPS can reverse the decrease of CRBP-I and RARα expression and even the increase of JNK1, p38 phosphorylation, active caspase 3, and apoptotic cell numbers induced by the increase of apo-/holo-RBP4 concentration ratio. These results are the first to indicate that an increase of apo-/holo-RBP4 concentration might increase cAMP/PKA/JNK1/p38 signaling leading to apoptosis via activation of STAT5/JAK2 signaling.

The retinoid/CRBP-I/RARα system is found to possess anti-inflammatory, anti-fibrotic, and anti-apoptotic actions in mesangial, endothelial, and tubular epithelial cells (33). Several investigators have reported that RAs inhibit apoptosis through both RAR-dependent and RAR-independent suppressive effects on JNK and p38 activity in several renal cell types (34). In several studies, CRBP has been thought of as a chaperone in retinoid metabolism (35–37). Others have indicated that effects of RAs are reduced by absence of CRBP-I and suppression of RARs (28, 38). In this study, the increased ratio of apo-/holo-RBP4 inhibited CRBP-I and RARα expression in HK-2 and HUVEC cells. The decrease of CRBP-I and RARα can be reversed by STRA6, JAK2, STAT5, JNK, and p38 siRNA and PKA inhibitor. Furthermore, CRBP-1 transfection can reverse the inhibition of RARα expression and the increase of p38 and JNK1 phosphorylation and active caspase 3 induced by the increase of apo-RBP4/holo-RBP4 concentration ratio in HK-2 cells. These results imply that increased apo-/holo-RBP4 ratio can activate apoptosis at least through its suppression on CRBP-I and RARα by STAT5/JAK2/cAMP-PKA/JNK1/p38 cascade in HK-2 cells. In a STRA6-deficient animal model for Matthew-Wood syndrome, nonspecific RBP4 excess, vitamin A deprivation, or RARα impairment in several tissues is thought to cause multisystem developmental malformations. These fatal consequences were largely alleviated by reducing embryonic RBP4 levels by morpholino oligonucleotide or pharmacological treatments (26). Apparently, the increase of nonfunctional RBP4 in Matthew-Wood syndrome has a role in inducing tissue damage. Similarly, our study showed that the increase of apo- to holo-RBP4 concentration ratio tightly binds STRA6 and possibly blocks RA uptake and suppresses CRBP-I and RARα mRNA and protein expression.

In this study, we propose that the increased ratio of serum apo- to holo-RBP4 concentration may influence the binding of RBP4 with STRA6 and cause apoptosis via mediating STRA6 signaling in subjects with impaired renal function. However, appropriate animal studies should be established to confirm this effect of increased apo-RBP4 concentration on renal and vascular injury.

In conclusion, our results are the first to indicate that the increased ratio of unbound- to bound-RBP4 may influence the binding activity with STRA6, trigger STAT5/JAK2 signaling, and sequentially activate AC6-catalyzed cAMP/PKA/JNK1/p38 pathway to suppress CRBP-I and RARα expression, finally causing apoptosis in renal and endothelial cells.

This work was supported by grants from the National Science Council of Taiwan (NSC-95-2314-B-037-040-MY3) and the Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital (KMUH98-7R21 and KMUH99-8R08).

- RBP4

- retinol-binding protein 4

- CRBP

- cellular retinol-binding protein

- RAR

- retinoic acid receptor

- HUVEC

- human umbilical vein endothelial cells

- Rp-cAMPS

- Rp-adenosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphorothioate.

REFERENCES

- 1. Soprano D. R., Soprano K. J., Goodman D. S. (1986) Retinol-binding protein messenger RNA levels in the liver and in extrahepatic tissues of the rat. J. Lipid Res. 27, 166–171 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Blaner W. S. (1989) Retinol-binding protein: the serum transport protein for vitamin A. Endocr. Rev. 10, 308–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bernard A., Vyskocyl A., Mahieu P., Lauwerys R. (1988) Effect of renal insufficiency on the concentration of free retinol-binding protein in urine and serum. Clin. Chim. Acta 171, 85–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Siegenthaler G., Saurat J. H. (1987) Retinol-binding protein in human serum: conformational changes induced by retinoic acid binding. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 143, 418–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kiernan U. A., Tubbs K. A., Nedelkov D., Niederkofler E. E., Nelson R. W. (2002) Comparative phenotypic analyses of human plasma and urinary retinol-binding protein using mass spectrometric immunoassay. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 297, 401–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Frey S. K., Nagl B., Henze A., Raila J., Schlosser B., Berg T., Tepel M., Zidek W., Weickert MO, Pfeiffer A. F., Schweigert F. J. (2008) Isoforms of retinol-binding protein 4 (RBP4) are increased in chronic diseases of the kidney but not of the liver. Lipids Health Dis. 7, 29–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yang Q., Graham T. E., Mody N., Preitner F., Peroni O. D., Zabolotny J. M., Kotani K., Quadro L., Kahn B. B. (2005) Serum retinol-binding protein 4 contributes to insulin resistance in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Nature 436, 356–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Graham T. E., Yang Q., Blüher M., Hammarstedt A., Ciaraldi T. P., Henry R. R., Wason C. J., Oberbach A., Jansson P. A., Smith U., Kahn B. B. (2006) Retinol-binding protein 4 and insulin resistance in lean, obese, and diabetic subjects. N. Engl. J. Med. 354, 2552–2563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chavez A. O., Coletta D. K., Kamath S., Cromack D. T., Monroy A., Folli F., DeFronzo R. A., Tripathy D. (2009) Retinol-binding protein 4 is associated with impaired glucose tolerance but not with whole body or hepatic insulin resistance in Mexican Americans. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 296, E758–E764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Raila J., Henze A., Spranger J., Möhlig M., Pfeiffer A. F., Schweigert F. J. (2007) Microalbuminuria is a major determinant of elevated plasma retinol-binding protein 4 in type 2 diabetic patients. Kidney Int. 72, 505–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Takebayashi K., Suetsugu M., Wakabayashi S., Aso Y., Inukai T. (2007) Retinol-binding protein 4 levels and clinical features of type 2 diabetes patients. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 92, 2712–2719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ziegelmeier M., Bachmann A., Seeger J., Lossner U., Kratzsch J., Blüher M., Stumvoll M., Fasshauer M. (2007) Serum levels of adipokine retinol-binding protein 4 in relation to renal function. Diabetes Care 30, 2588–2592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Henze A., Frey S. K., Raila J., Tepel M., Scholze A., Pfeiffer A. F., Weickert M. O., Spranger J., Schweigert F. J. (2008) Evidence that kidney function but not type 2 diabetes determines retinol-binding protein 4 serum levels. Diabetes 57, 3323–3326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Henze A., Frey S. K., Raila J., Scholze A., Spranger J., Weickert M. O., Tepel M., Zidek W., Schweigert F. J. (2010) Alterations of retinol-binding protein 4 species in patients with different stages of chronic kidney disease and their relation to lipid parameters. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 393, 79–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chang Y. H., Lin K. D., Wang C. L., Hsieh M. C., Hsiao P. J., Shin S. J. (2008) Elevated serum retinol-binding protein 4 concentrations are associated with renal dysfunction and uric acid in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 24, 629–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Blaner W. S. (2007) STRA6, a cell surface receptor for retinol-binding protein: the plot thickens. Cell Metab. 5, 164–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kawaguchi R., Yu J., Honda J., Hu J., Whitelegge J., Ping P., Wiita P., Bok D., Sun H. (2007) A membrane receptor for retinol-binding protein mediates cellular uptake of vitamin A. Science 315, 820–825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nezzar H., Chiambaretta F., Marceau G., Blanchon L., Faye B., Dechelotte P., Rigal D., Sapin V. (2007) Molecular and metabolic retinoid pathways in the human ocular surface. Mol. Vis. 13, 1641–1650 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Berry D. C., Jin H., Majumdar A., Noy N. (2011) Signaling by vitamin A and retinol-binding protein regulates gene expression to inhibit insulin responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 4340–4345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kyriakis J. M., Avruch J. (2001) Mammalian mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathways activated by stress and inflammation. Physiol. Rev. 81, 807–869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tian W., Zhang Z., Cohen D. M. (2000) MAPK signaling and the kidney. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 279, F593–F604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Singh A. B., Guleria R. S., Nizamutdinova I. T., Baker K. M., Pan J. (August 31, 2011) High glucose-induced repression of RAR/RXR in cardiomyocytes is mediated through oxidative stress/JNK signaling. J. Cell. Physiol. 10.1002/jcp.23005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lejeune D., Dumoutier L., Constantinescu S., Kruijer W., Schuringa J. J., Renauld J. C. (2002) Interleukin-22 (IL-22) activates the JAK/STAT, ERK, JNK, and p38 MAP kinase pathways in a rat hepatoma cell line: pathways that are shared with and distinct from IL-10. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 33676–33682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tripathi A., Sodhi A. (2008) Prolactin-induced production of cytokines in macrophages in vitro involves JAK/STAT and JNK MAPK pathways. Int. Immunol. 20, 327–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fuster G., Almendro V., Fontes-Oliveira C. C., Toledo M., Costelli P., Busquets S., López-Soriano F. J., Argilés J. M. (2011) Interleukin-15 affects differentiation and apoptosis in adipocytes: implications in obesity. Lipids 46, 1033–1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Isken A., Golczak M., Oberhauser V., Hunzelmann S., Driever W., Imanishi Y., Palczewski K., von Lintig J. (2008) RBP4 disrupts vitamin A uptake homeostasis in a STRA6-deficient animal model for Matthew-Wood syndrome. Cell Metab. 7, 258–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jaconi S., Saurat J. H., Siegenthaler G. (1996) Analysis of normal and truncated holo- and apo-retinol-binding protein (RBP) in human serum: altered ratios in chronic renal failure. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 134, 576–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bouillet P., Sapin V., Chazaud C., Messaddeq N., Décimo D., Dollé P., Chambon P. (1997) Developmental expression pattern of Stra6, a retinoic acid-responsive gene encoding a new type of membrane protein. Mech. Dev. 63, 173–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kawaguchi R., Yu J., Wiita P., Ter-Stepanian M., Sun H. (2008) Mapping the membrane topology and extracellular ligand binding domains of the retinol-binding protein receptor. Biochemistry 47, 5387–5395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Heller J. (1975) Interactions of plasma retinol-binding protein with its receptor: specific binding of bovine and human retinol-binding protein to pigment epithelium cells from bovine eyes. J. Biol. Chem. 250, 3613–3619 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kumar S., Kostin S., Flacke J. P., Reusch H. P., Ladilov Y. (2009) Soluble adenylyl cyclase controls mitochondria-dependent apoptosis in coronary endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 14760–14768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ingelsson E., Sundström J., Melhus H., Michaëlsson K., Berne C., Vasan R. S., Risérus U., Blomhoff R., Lind L., Arnlöv J. (2009) Circulating retinol-binding protein 4, cardiovascular risk factors and prevalent cardiovascular disease in elderly. Atherosclerosis 206, 239–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Xu Q., Lucio-Cazana J., Kitamura M., Ruan X., Fine L. G., Norman J. T. (2004) Retinoids in nephrology: promises and pitfalls. Kidney Int. 66, 2119–2131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Xu Q., Konta T., Furusu A., Nakayama K., Lucio-Cazana J., Fine L. G., Kitamura M. (2002) Transcriptional induction of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase 1 by retinoids: selective roles of nuclear receptors and contribution to the antiapoptotic effect. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 41693–41700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Molotkov A., Ghyselinck N. B., Chambon P., Duester G. (2004) Opposing actions of cellular retinol-binding protein and alcohol dehydrogenase control the balance between retinol storage and degradation. Biochem. J. 383, 295–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Napoli J. L. (2000) A gene knockout corroborates the integral function of cellular retinol-binding protein in retinoid metabolism. Nutr. Rev. 58, 230–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ghyselinck N. B., Båvik C., Sapin V., Mark M., Bonnier D., Hindelang C., Dierich A., Nilsson C. B., Håkansson H., Sauvant P., Azaïs-Braesco V., Frasson M., Picaud S., Chambon P. (1999) Cellular retinol-binding protein I is essential for vitamin A homeostasis. EMBO J. 18, 4903–4914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zizola C. F., Frey S. K., Jitngarmkusol S., Kadereit B., Yan N., Vogel S. (2010) Cellular retinol-binding protein type I (CRBP-I) regulates adipogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30, 3412–3420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]