Background: Adaptation to oxidative stress involves increased expression of 20 S proteasome, Pa28αβ, and immunoproteasome.

Results: Blocking Nrf2 prevents proteasome and Pa28αβ induction, and Nrf2 is required for full adaptation.

Conclusion: Adaptation occurs through Nrf2-dependent induction of 20 S proteasome and Pa28αβ, whereas immunoproteasome is induced independently.

Significance: The Nrf2 signal transduction pathway controls 20 S proteasome/Pa28αβ contributions to stress-adaptation, but not immunoproteasome contributions.

Keywords: Nrf2, Oxidative Stress, Proteasome, Signal Transduction, Stress Response, Adaptation, Immunoproteasome, Pa28, Hormesis

Abstract

The ability to adapt to acute oxidative stress (e.g. H2O2, peroxynitrite, menadione, and paraquat) through transient alterations in gene expression is an important component of cellular defense mechanisms. We show that such adaptation includes Nrf2-dependent increases in cellular capacity to degrade oxidized proteins that are attributable to increased expression of the 20 S proteasome and the Pa28αβ (11 S) proteasome regulator. Increased cellular levels of Nrf2, translocation of Nrf2 from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, and increased binding of Nrf2 to antioxidant response elements (AREs) or electrophile response elements (EpREs) in the 5′-untranslated region of the proteasome β5 subunit gene (demonstrated by chromatin immunoprecipitation (or ChIP) assay) are shown to be necessary requirements for increased proteasome/Pa28αβ levels, and for maximal increases in proteolytic capacity and stress resistance; Nrf2 siRNA and the Nrf2 inhibitor retinoic acid both block these adaptive changes and the Nrf2 inducers dl-sulforaphane, lipoic acid, and curcumin all replicate them without oxidant exposure. The immunoproteasome is also induced during oxidative stress adaptation, contributing to overall capacity to degrade oxidized proteins and stress resistance. Two of the three immunoproteasome subunit genes, however, contain no ARE/EpRE elements, and Nrf2 inducers, inhibitors, and siRNA all have minimal effects on immunoproteasome expression during adaptation to oxidative stress. Thus, immunoproteasome appears to be (at most) minimally regulated by the Nrf2 signal transduction pathway.

Introduction

Despite antioxidant defenses, such as superoxide dismutases and glutathione peroxidases, oxidative stress represents a constant danger to cell and organismal viability. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species can cause protein, lipid, sugar, DNA, and RNA modification. Oxidative modifications to proteins are common, and a major cellular defense strategy is to rapidly degrade mildly oxidized proteins before they can aggregate and cross-link to form insoluble cell inclusion bodies (1–16). Insufficient proteolytic capacity or increased oxidant generation, or both, can result in compromised cell function or even cell death (1, 12, 17–24). Over a period of many years, we (1–6, 15) and others (11–14, 16, 25) have demonstrated that the bulk of oxidatively damaged proteins in the cytoplasm, endoplasmic reticulum, and nucleus are degraded by the proteasome. More recently, we have also shown that the immunoproteasome plays a significant role (26, 27). In mitochondria, oxidized proteins are preferentially degraded by the Lon protease (7–10, 28).

In previous studies, we have demonstrated that mammalian cells, as well as bacteria and yeast, can transiently adapt to oxidative stress (19, 26, 29–31). This is an adaptive process (sometimes called hormesis) in which cells treated with a mild dose of an oxidant will, for a period of time (≈24–48 h), become more resistant to a higher dose of the same (or related) oxidant that would normally be toxic. Recently, we have demonstrated that this adaptive response includes an increased abundance of 20 S proteasomes, immunoproteasomes, and Pa28αβ (or 11 S) proteasome regulators (26); all these proteins were shown to play key roles in the oxidative stress response, and each was required for full adaptation. Other groups have also reported induction of various forms of the proteasome, and proteasome regulators, by oxidative stress (32–36).

The nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 (Nrf2)2 transcription factor is an important component of responses to oxidative stress (37–44). Under non-stressful conditions, Nrf2 is maintained at low levels through rapid degradation via Keap1-dependent ubiquitin conjugation (44–46), followed by targeted degradation by the 26 S proteasome. As a product of this rapid turnover, newly translated Nrf2 is found predominantly in the cytoplasm. With Keap1 inactivation, as a product of factors such as oxidative stress, Nrf2 levels increase due to diminished proteasomal degradation, and Nrf2 is phosphorylated and translocated to the nucleus in mechanisms mediated by PKCδ and Akt (47). Once in the nucleus, Nrf2 binds to a cis-acting enhancer sequence, upstream of numerous antioxidant genes, known as the antioxidant response element (ARE) or electrophile responsive element (EpRE), and promotes the synthesis of several antioxidants, and enzymes responsible for repairing/removing oxidative damage and restoring cell viability (37).

It has been shown that Nrf2 knock-out in mice results in decreased tolerance to oxidative stress (48, 49). Additionally, results by Kwak et al. (44) showed that the phenolic antioxidant [3H]1,2-dithiole-3-thione, which induces many cellular antioxidants and phase 2 enzymes, can also enhance mammalian proteasome expression through the Keap1-Nrf2 signaling pathway. These results led us to hypothesize that the transient stress adaptation, involving proteasome and proteasome regulators, which we described previously (26), might be primarily under the control of the Nrf2 transcription factor. In the present study we have, therefore, tested whether oxidative stress-induced increases in 20 S proteasome, immunoproteasome, and the Pa28αβ regulator, as well as increased stress resistance, are actually under the control of Nrf2, and whether Nrf2 is necessary and/or sufficient for their induction and for adaptation to various forms of oxidative stress.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

All materials were purchased from VWR unless otherwise stated. Murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEF), catalog number CRL-2214, were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). Cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), catalog number 10-013-CV, from Mediatech (Manassas, VA) and supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (catalog number SH30070.03) from Hyclone (Logan, UT): henceforth referred to as “complete medium.” Cells were typically incubated at 37 °C under 5% CO2 and ambient oxygen.

Adaptation to Oxidants

MEF cells were grown to 10% confluence (≈250,000 cells/ml) then pretreated with 100 nm to 100 μm H2O2 (catalog number H1009-100 ml) from Sigma, 1 nm to 1 μm peroxynitrite (catalog number 516620) from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany), 0.2–100 nm menadione (catalog number ME105) from Spectrum Chemicals (Gardena, CA), or 10 pm to 100 nm paraquat (catalog number PST-740AS) from Ultra Scientific (Kingstown, RI), for 1 h at 37 °C under 5% CO2 to induce adaptation to oxidative stress. Cells were then washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), which was finally replaced with fresh complete medium.

Induction or Inhibition of Nrf2

MEF cells were grown to 5% confluence and treated with varying concentrations of Nrf2 inducers. dl-Sulforaphane (catalog number S2441-5 mg) or curcumin (catalog number C1386-5G) from Sigma. Lipoic acid (catalog number L1089) was purchased from Spectrum Chemicals, dissolved in N,N-dimethylformaldehyde, and combined with complete medium at a final concentration of 0.1%; and a comparable concentration of N,N-dimethylformaldehyde was added to control cells. Curcumin was dissolved in ethanol and combined with complete medium at a final concentration of 0.1%, and a comparable concentration of ethanol was added to control cells. In some assays cells were treated with the Nrf2 inhibitor all-trans-retinoic acid (catalog number R2625-100MG) purchased from Sigma. trans-Retinoic acid was dissolved in ethanol and combined with complete medium at a final concentration of 0.1%; a comparable concentration of ethanol was added to control cells.

Western Blot Analysis

MEF cells were harvested from 25–75-cm2 flasks by trypsinization. Cells were washed twice with PBS to remove trypsin and then lysed in RIPA buffer, (catalog number 89901) from Thermo Fisher (Waltham, MA), supplemented with protease inhibitor mixture (catalog number 11836170001) from Roche Applied Science. Protein content was quantified with the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For Western analysis, 5–20 μg of protein was run on SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. Using standard Western blot techniques, membranes were treated with proteasome regulator subunit Pa28α antibodies (catalog number PW8185-0100) from Enzo Life Sciences (Plymouth Meeting, PA), immunoproteasome subunit anti-LMP2/β1i antibody (catalog number ab3328) was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA), 20 S proteasome anti-β1 antibody (catalog number sc-67345) or anti-Nrf2 antibody (catalog number sc-722) were both from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). The blocking buffer employed for Western blotting was StartingblockTM buffer (catalog number 37539) from Thermo Fisher and the wash buffer was 1× PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20. An enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Pierce) was used for chemiluminescent detection and membranes were analyzed using the biospectrum imaging system (UVP, Upland, CA).

siRNA “Knockdown” of Nrf2 or Proteasome

Nrf2 (catalog number sc-37049), β1 (catalog number sc-62865), β1i (Lmp2) (catalog number sc-35821), Pa28α (catalog number sc-151977), and Scrambled Control (catalog number sc-37007) siRNA were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. For experiments with these siRNAs, MEF were seeded at a density of 100,000 cells/well in 6- or 48-well plates and grown to 10% confluence. siRNA treatment was then performed as described in the Santa Cruz Biotechnology product manual.

Fluoropeptide Proteolytic Assays

MEF were harvested by cell scraping in phosphate buffer. Cells were then re-suspended in 50 mm Tris, 25 mm KCl, 10 mm NaCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 1 mm DTT (pH 7.5) and lysed by 3 freeze-thaw cycles. Protein was quantified using a BCA Protein Assay Kit. Then 5.0 μg of cell lysate per sample was transferred in triplicate to 96-well plates, and 2 μm of N-succinyl-Leu-Leu-Val-Tyr-AMC (catalog number 80053-860) purchased from VWR was then added to the plates. Plates were incubated at 37 °C and mixed at 300 rpm for 4 h. Fluorescence readings were taken at 10-min intervals using an excitation wavelength of 355 nm and an emission of 444 nm. Following subtraction of background fluorescence, fluorescence units were converted to moles of free AMC, with reference to an AMC standard curve of known amounts of AMC (catalog number 164545) purchased from Merck (Whitehouse Station, NJ). In some experiments, cells were treated with 1 μm of the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (catalog number 474790) from Merck (Whitehouse Station, NJ) or 5 μm of the proteasome inhibitor lactacystin (catalog number 80052-806) from VWR, 30 min prior to incubation and addition of substrates. MG132 was dissolved in DMSO at a ×100 concentration and combined with samples at a concentration of 1%. In these experiments, control cells were treated with an equivalent concentration of plain DMSO.

Proteolytic Assay of Radiolabeled Proteins

Tritium-labeled hemoglobin ([3H]Hb) was generated in vitro as described previously (4–6, 15, 26) using the [3H]formaldehyde and sodium cyanoborohydride method of Jentoft and Dearborn (50), and then extensively dialyzed. Before dialysis, some purified radiolabeled proteins were oxidatively modified by exposure to 1.0 mm H2O2 for 1 h to generate oxidized substrates. All substrates were then incubated with cell lysates to measure proteolysis. Percentage of protein degraded for both Hb and oxidized Hb was calculated by release of acid-soluble (supernatant) counts, by liquid scintillation after addition of 20% TCA (trichloroacetic acid) and 3% BSA (as carrier) to precipitate remaining intact proteins (5, 12, 15, 26), in which % degradation = 100 × (acid-soluble counts − background counts)/total counts.

Cell Counting Assay

Cells were seeded in 100-μl samples at a density of 100,000 cells/ml in 48-well plates. Twenty-four hours after seeding, some cells were pretreated with an oxidant or an Nrf2 inducer. At 48 h after seeding, cells were challenged with a toxic dose of 100 μm to 1 mm hydrogen peroxide for 1 h followed by addition of fresh complete medium. Cells were harvested 24 h after challenge, using trypsinization. The cell density of 100-μl samples of cell suspensions was then obtained using a Cell Counter purchased from Beckman Coulter (Fullerton, CA).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assay

Four million cells were prepared at 10% confluence, the cells were exposed to either 0 or 1 μm H2O2 for 1 h. ChIP analysis was performed using the reagents and methods provided in a Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay Kit (catalog number 17-295) purchased from Millipore (Temecula, CA). Briefly cells were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min, washed twice with PBS, dislodged through scraping, and re-suspended in 1 ml of 1% SDS lysis buffer containing protease inhibitor. Samples were sonicated using 10 bursts of 5 s, output of 50 watts (Branson Sonifier 140, Branson Ultrasonic, Danbury, CT), and then centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was removed and diluted in a 10-fold excess of ChIP dilution buffer (1% of samples were removed at this point to later form the input samples). Samples were pre-cleared using a 30-min incubation with 30 μl/ml of salmon sperm DNA/Protein A-agarose slurry. Samples were then incubated for 1 h with 8 μg/ml of Nrf2 antibody (catalog number sc-13032) purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, then 30 μl/ml of salmon sperm DNA/Protein A-agarose slurry was added and samples were incubated overnight at 4 °C under gentle agitation. After this, the bead slurry was subjected to sequential 10-min washes with low salt immune complex, high salt immune complex, LiCl immune complex, and TE buffer. Samples were detached from the bead slurry with two washes of 250 μl of 1% SDS, 0.1 m NaHCO3, then reverse cross-linked by incubation with 200 μm NaCl for 4 h at 65 °C. 10 μm EDTA, 40 μm Tris-HCl, and 20 μg of proteinase K were then added to the samples, and the samples were incubated for 1 h at 45 °C. DNA was isolated and purified from the samples using phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol. PCR was then performed on samples as described below. 5 μl of DNA from each sample was combined with 15 μl of the PCR SYBR Green Master Mix purchased from Applied Biosystems, 1.5 μl each of 5 μm working solutions of forward and reverse PSMB5 primers designed by Kwak et al. (44) (catalog number 2110654) and purchased from Invitrogen, and 7 μl of DNase/RNase-free ddH2O. The forward primer sequence used was CAGACCGGCGCTGGTATTTAGAGG and the reverse primer sequence was TAGCCAGCGCCATGTTTAGCAAGG. PCR was carried out in a 7500 Real Time PCR System device from Applied Biosystems, using an annealing temperature of 61 °C and an extension temperature of 72 °C, for a total of 55 cycles. PCR products were then examined on a 1% agarose gel containing 0.001% ethidium bromide.

Real Time PCR Assay of mRNA Levels

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent and treated with DNA-free reagent according to the manufacturer's (Invitrogen, catalog number 1908) protocol to remove DNA. RNA samples were then reverse transcribed using the TaqMan random hexamers (catalog number N808-0234) purchased from Applied Biosystems and the mRNA levels were measured by real time PCR (RT-PCR) using a 7500 real time PCR system purchased from Applied Biosystems. In brief, 5 μl of reverse transcription reaction product was added to a reaction tube containing 12.5 μl of SYBR Green PCR Master Mix, 5.5 μl of sterile water, and 1 μl of a 5 μm working solution of each primer (forward and reverse) for the proteasome β5 subunit or GAPDH mRNA. The total PCR sample was 25 μl. The primer sequences used were as follows: 20 S proteasome subunit β5, 5′-GCTGGCTAACATGGTGTATCAT-3 and 5′-AAGTCAGCTCATTGTCACTGG-3 as used previously (44) and GAPDH, 5′-GATGCAGGGATGATGTTC-3′ and 5′-TGCACCACCAACTGCTTAG-3′.

RESULTS

H2O2, Peroxynitrite, Paraquat, and Menadione Pretreatment All Increase Proteolytic Capacity

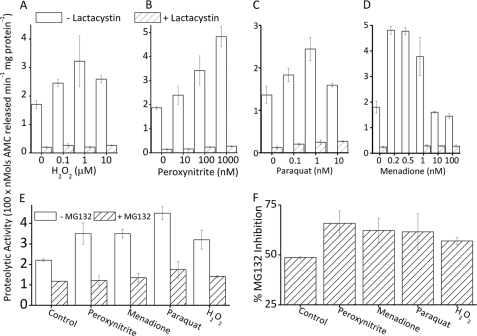

We have previously reported that adaptation to H2O2 includes large increases in proteasomal proteolytic capacity (26). We now needed to determine whether the increase in proteasome is specific to H2O2, or if it is a more general response to oxidants. We first pretreated MEF cells with various concentrations of H2O2, peroxynitrite, or the redox cycling agents paraquat and menadione for 1 h. Then, 24 h later, we harvested and lysed the cells and measured the proteolytic capacity by degradation of the fluorogenic peptide, Suc-LLVY-AMC, which is widely used to estimate the chymotrypsin-like activity of the proteasome (5, 26, 51). We saw a 2-fold increase in proteolytic capacity with H2O2 or paraquat pretreatment, a 2.5-fold increase with peroxynitrite pretreatment, and a 2–3-fold increase with menadione pretreatment (Fig. 1, A–D). In lysates of untreated cells, the selective proteasome inhibitor lactacystin caused an 80–90% inhibition of proteolysis. In lysates of oxidant-pretreated cells, lactacystin inhibited degradation by 90–95%, indicating that proteasome is largely responsible for most of the oxidant-induced adaptive increase in proteolytic capacity (Fig. 1, A–D). This experiment was repeated using another proteasome-selective inhibitor, MG132, which blocked 50% of activity in untreated cells, and 60% of activity following oxidative stress adaptation (Fig. 1, E and F).

FIGURE 1.

Oxidant pretreatment increases proteolytic capacity in a proteasome-dependent manner. Cells treated with a mild dose of a range of oxidants exhibit increased proteolytic capacity, the majority of which (80–95%) are blocked by the proteasome selective inhibitor lactacystin. MEF cells were grown to 10% confluence (≈250,000 cells per ml) and treated with: A, 0–100 μm H2O2; B, 0–1 μm peroxynitrite; C, 0–100 nm paraquat; or D, 0–100 nm menadione. All treatments were for 1 h in complete medium, following which the medium was removed and replaced with fresh complete medium (see ”Experimental Procedures“). After 24 h, cells were lysed and diluted to a protein concentration of 50 μg/ml. Proteolytic capacity was determined by cleavage of the proteasome chymotrypsin-like substrate Suc-LLVY-AMC (see ”Experimental Procedures“). Where used, 5 μm lactacystin was added to samples 30 min prior to incubation with Suc-LLVY-AMC. Values are mean ± S.E., n = 3. E, MEF cells were prepared as described in A and pretreated with 100 nm peroxynitrite, 1 μm H2O2, 1 nm menadione, or 1 nm paraquat for 1 h in complete medium; following this, the medium was removed and replaced with fresh complete medium. In some samples, 1 μm MG132 was added 30 min prior to incubation with Suc-LLVY-AMC. Cells were incubated, harvested, lysed, diluted, and analyzed for proteolytic capacity by lysis of the fluorogenic peptide Suc-LLVY-AMC, as in panels A–D, and under ”Experimental Procedures.“ Values are mean ± S.E., n = 3. F, results from E were re-plotted with the decrease in activity resulting from addition of MG132 plotted as a percent of the proteolytic capacity of cells not treated with the inhibitor.

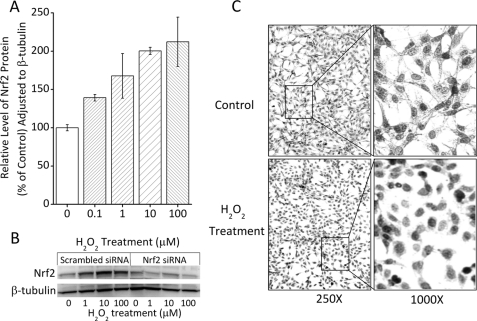

H2O2 Adaptation Increases Nrf2 Protein Levels and Nrf2 Nuclear Translocation

ARE/EpRE sequences are present in the upstream untranslated region of all 20 S proteasome subunit genes examined. If Nrf2 is involved in our model of adaptation to oxidative stress, we would expect to see an increase in total Nrf2 protein levels as a product of enhanced stability following detachment from the Keap1 complex, as well as translocation of Nrf2 from the cytosol to the nucleus: indicative of Nrf2 functioning as a nuclear transcription factor (39, 40, 45). For initial experiments we used H2O2 as our adaptive oxidant and found that a mild dose of H2O2 caused a 2-fold increase in cellular Nrf2 levels (Fig. 2A); this is consistent with previous reports of stress-related induction of Nrf2 (38, 40, 42, 44, 45). When we blocked Nrf2 synthesis, using Nrf2 siRNA, we lost the increase in Nrf2 protein (Fig. 2B). We next examined Nrf2 localization using immunocytochemistry, and saw a notably stronger nuclear-localized staining of Nrf2 in H2O2-treated cells compared with a more widespread staining of all cell compartments in untreated cells (Fig. 2C).

FIGURE 2.

Nrf2 protein levels and nuclear translocation during oxidative stress adaptation. A, H2O2 treatment causes an increase in whole cell levels of Nrf2. MEF cells were grown to 10% confluence, treated for 1 h with 0–100 μm H2O2, and then washed and resuspended (see ”Experimental Procedures“). Cells were harvested and lysed 24 h following oxidant pretreatment as described for the Western blot under ”Experimental Procedures.“ Cell lysates (20 μg) were run on SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. The membranes were screened with antibodies directed against Nrf2 and β-tubulin and results were quantified by densitometry. All experiments were repeated in triplicate and densitometric band intensities for Nrf2 were normalized to those of β-tubulin. Values are mean ± S.E., n = 3. B, the increase in Nrf2 band intensity is lost with Nrf2 siRNA pretreatment. Samples were prepared as in panel A except that 4 h prior to H2O2 treatment, cells were pretreated with siRNA against Nrf2, or with a scrambled vector, and gels were then run as in panel A. C, treatment of cells with H2O2 causes Nrf2 to shift from a broad cytoplasmic distribution to a nuclear localization. MEF cells were grown to 50% confluence and treated with 100 μm H2O2 for 1 h, then fixed and stained with an antibody directed against Nrf2, as described under ”Experimental Procedures.“ Representative photographs are shown, but the experiment was repeated several times with similar results.

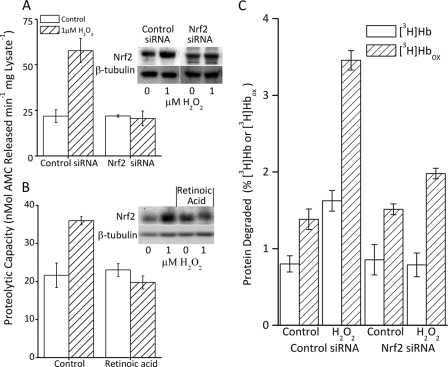

Nrf2 Is an Important Regulator for H2O2-induced Increase in Proteolytic Capacity

Having determined that Nrf2 levels were increased, and that Nrf2 was translocated to the nucleus under the conditions of our cellular H2O2 adaptation model, we next wanted to determine whether Nrf2 is actually required for the increased proteolytic capacity reported in Fig. 1. To examine this we blocked Nrf2 expression by two distinct methods: siRNA and retinoic acid. First, we explored an Nrf2 siRNA treatment level and time period that would not diminish basal Nrf2 levels, as Nrf2 is maintained at extremely low levels in unstressed cells, but would block adaptive increases in Nrf2. As shown in both Fig. 2B and the inset to Fig. 3A, we were successful in blocking the oxidative stress-induced increase in Nrf2 levels, without reducing the basal levels of Nrf2. Cells pretreated with Nrf2 siRNA and then exposed to an adaptive dose of H2O2 did not exhibit an H2O2-induced increase in proteolytic capacity, but cells treated with a scrambled siRNA vector showed normal induction of proteolytic capacity (Fig. 3A). As a further test of Nrf2 involvement, we repeated the experiment of Fig. 3A using retinoic acid treatment, which has been shown to prevent Nrf2 expression in cells (52), as a different means of blocking Nrf2. When we pretreated cells with retinoic acid and then attempted to adapt the cells to H2O2 as in Fig. 3A, we saw no significant increase in Nrf2 levels, and no increase in proteolytic capacity (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 3.

Increased proteolytic capacity is blocked by inhibition of Nrf2. A, the increase in proteolytic capacity caused by H2O2 treatment was blocked by inhibition of Nrf2 expression through pretreatment with Nrf2 siRNA. MEF cells were grown to 10% confluence and treated with either control or Nrf2 siRNA for 24 h as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Then, 4 h after initiation of siRNA treatment, half the cells were exposed to 1 μm H2O2 for 1 h, washed, and resuspended (see ”Experimental Procedures“). The capacity to degrade the fluorogenic peptide Suc-LLVY-AMC was determined 24 h after initiation of siRNA treatment (see ”Experimental Procedures“). Values are mean ± S.E., n = 3. The inset to panel A shows a representative Western blot. B, treatment of cells with the Nrf2 inhibitor retinoic acid also blocked the H2O2-induced increase in proteolytic capacity. MEF cells were seeded at 5% confluence and treated with 3 μm retinoic acid. When cells reached 10% confluence one-half were exposed to 1 μm H2O2 and proteolytic capacity (Suc-LLVY-AMC lysis) was determined 24 h after treatment as in panel A. Values are mean ± S.E., n = 3. The inset to panel B shows a representative Western blot. C, the H2O2-induced increase in selective capacity to degrade oxidized proteins is also blocked by inhibition of Nrf2 expression. MEF cells were prepared and lysed as described in panels A and B. Lysates were incubated for 4 h with [3H]Hb or [3H]Hbox. Percent protein degraded was calculated after addition of 20% TCA and 3% BSA, and centrifugation to precipitate the remaining intact proteins (5, 12, 15, 26). Percent protein degradation was determined by release of acid soluble counts in TCA supernatants, by liquid scintillation as follows: % degradation = (acid soluble counts − background counts)/total counts × 100. Results are mean ± S.E., n = 3.

Nrf2 Is an Important Regulator of the H2O2-induced Increase in Proteolytic Capacity to Degrade Oxidized Proteins

Although the degradation of Suc-LLVY-AMC provides a good approximation of the chymotrypsin-like activity of the proteasome, what really counts is the proteasomal capacity to degrade oxidized proteins. To examine this question, we incubated cell lysates with tritium-labeled hemoglobin ([3H]Hb) and oxidized [3H]hemoglobin ([3H]Hbox). Adaptation to H2O2 pretreatment caused a 2-fold increase in capacity to degrade [3H]Hb, but an almost 4-fold increase in selectivity for [3H]Hbox (Fig. 3C). In contrast, cells pretreated with siRNA against Nrf2, prior to H2O2 treatment, exhibited no increase in [3H]Hb degradation and less than a 25% increase in capacity to degrade [3H]Hbox (Fig. 3C). The results of Fig. 3 provide strong evidence that Nrf2 has an important role in the increase in proteolytic capacity induced during adaptation to oxidative stress.

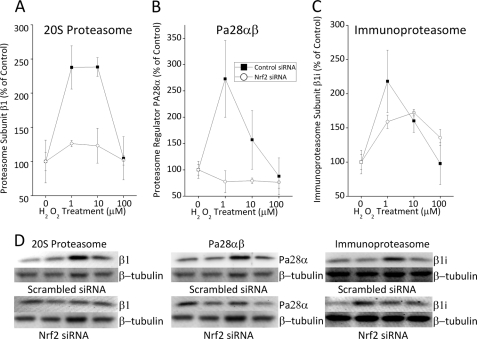

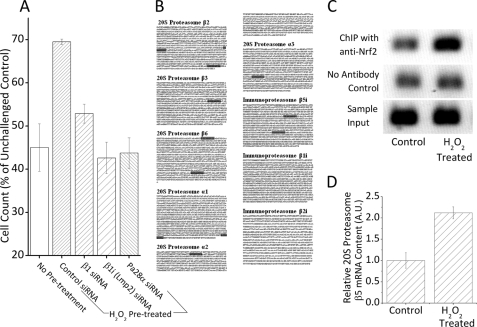

Nrf2 Regulates H2O2-induced Expression of 20 S Proteasome and Pa28αβ but Not Immunoproteasome

Because oxidative stress can increase the levels of 20 S proteasome, immunoproteasome, and the proteasome regulator Pa28αβ (26, 32, 33, 35, 53, 54), all of which have been shown to have critical roles in adaptation to oxidative stress (26, 32, 33, 35, 53, 54), we wanted to determine whether the increases in proteolytic capacity reported in Fig. 3 are explained by changes in proteasome, and to determine whether Nrf2 plays a critical upstream role. For these studies, we used Western blot analyses of control and H2O2-adapted cells, pretreated with either Nrf2 siRNA or a scrambled siRNA vector. With scrambled (control) siRNA treatment we saw a 2–3-fold H2O2-induced increase in 20 S proteasome, immunoproteasome, and Pa28αβ protein levels (Fig. 4, A–C). With Nrf2 siRNA pretreatment, however, the H2O2-induced increase in 20 S proteasome (Fig. 4A) and Pa28αβ (Fig. 4B) was lost, indicating that 20 S proteasome and Pa28αβ are regulated by Nrf2 during adaptation to stress. In contrast to 20 S proteasome and Pa28αβ, Nrf2 siRNA treatment had only a weak effect on the H2O2-induced increase in immunoproteasome levels (Fig. 4C). Nevertheless, H2O2-mediated increases in 20 S proteasome, immunoproteasome, and Pa28αβ were clearly all important for adaptive increases in cell tolerance (survival) of H2O2 challenge treatments (Fig. 5A). Thus, we must conclude that immunoproteasome regulation during oxidative stress is either wholly or partially independent of Nrf2, and other factor(s) must be involved. In support of this idea, we find that, although 20 S proteasome subunits contain a few ARE/EpRE sequences in their promoter regions, ARE/EpRE sequences are completely absent in two of the three immunoproteasome-specific subunits (Fig. 5B). Although such analyses are not conclusive, the results are certainly suggestive. We confirmed that at least some of the EpRE elements upstream of 20 S proteasome subunits are not only present, but H2O2 induces binding of Nrf2 to these sequences. To test this we performed a ChIP assay on an EpRE element in the 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR) of the proteasome β5 subunit gene, which has previously been shown to have functional EpRE elements (44). This EpRE element showed a strong increase in Nrf2 binding under H2O2 exposure (Fig. 5C), thus demonstrating that 20 S proteasome induction under our H2O2 adaptation conditions is mediated by the Nrf2 signal transduction pathway. Using RT-PCR, we were also able to demonstrate a corresponding, hydrogen peroxide-induced, 2-fold increase in cellular mRNA levels of the 20 S proteasome β5 subunit during the same time period (Fig. 5D).

FIGURE 4.

H2O2-induced expression of proteasome and proteasome regulators is Nrf2 dependent. H2O2 treatment causes an increase in 20 S proteasome (A) and the proteasome regulator Pa28αβ (B), both of which appear to depend upon Nrf2 expression. The increase in immunoproteasome (C) with H2O2 treatment may be only partly Nrf2 dependent, at best. MEF cells were prepared, treated, and harvested as described in the legend to Fig. 3. The cells were then lysed, and samples were run on SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to PVDF membranes as described in the legend to Fig. 2. Membranes were treated with antibodies directed against 20 S proteasome subunit β1, immunoproteasome subunit β1i (LMP2), proteasome regulator subunit PA28α, Nrf2, and β-tubulin. Graphs in A–C show the levels of 20 S proteasome β1 subunit (panel A), Pa28α regulator (panel B), and immunoproteasome β1i or LMP2 (panel C) each divided by β-tubulin levels for each well and then plotted as a percent of control. Values are mean ± S.E., n = 3. D, representative Western blots for β1, β-tubulin, β1i (LMP2), and Pa28α (all ± Nrf2 siRNA) for graphs in A-C.

FIGURE 5.

20 S proteasome is required for H2O2 adaptation, and contains active EpRE elements. A, MEF cells were grown, and incubated with siRNA directed against, 20 S proteasome subunit β1, immunoproteasome subunit β1i (LMP2), proteasome regulator subunit Pa28α, or a scrambled vector, then pretreated with 1 μm H2O2 as described in the legend to Fig. 3. After 24 h, cells were challenged with a dose of 1 mm H2O2 for 1 h, washed, and resuspended in fresh complete medium. After another 24 h, cells were harvested and cell counts were taken. Values are plotted as a percent of unchallenged samples treated with scrambled siRNA, which had an average cell density of 110,000 cells/ml at the point of counting. Values are mean ± S.E., n = 4. B, ARE/EpRE consensus sequences (TGANNNNGC/GCNNNNTCA) are present upstream of all 20 S proteasome and immunoproteasome subunit genes. Data represent sequences 5 kb upstream of promoters, based on the NCBI database of Mus musculus. ARE/EpRE sequences are highlighted. C, H2O2 treatment causes increased binding of Nrf2 to one of the EpRE elements upstream of the promoter of the proteasome β5 subunit gene. Cells were grown to 10% confluence then exposed to 1 μm H2O2 for 1 h. ChIP analysis was then performed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Nonspecific binding was measured through performing a ChIP assay in the absence of the Nrf2 antibody and input was as an internal control by representing 1% of the sample prior immunoprecipitation. D, H2O2 treatment causes increased mRNA expression of the 20 S proteasome β5 subunit. Cells were grown to 10% confluence, then exposed to 1 μm H2O2 for 1 h. After this cells were harvested, the mRNA levels of the 20 S proteasome subunit β5 and the loading control GAPDH were then determined through reverse transcriptase PCR followed by quantitative PCR. Values are plotted, in arbitrary units, adjusted by levels of GAPDH. Values are mean ± S.E., where n = 3.

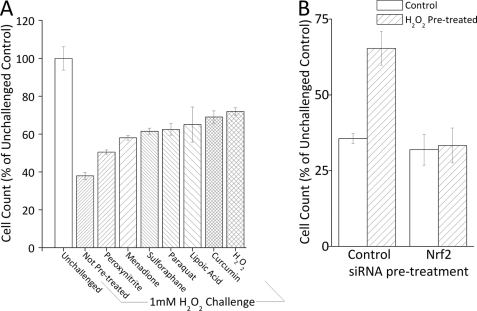

Pretreatment with Nrf2 ”Inducers“ Causes Increased Tolerance to Oxidative Stress

We have developed a transient oxidative stress-adaptive model in which pretreatment of cells with a low concentration of H2O2 causes changes in gene expression that permit survival of a much higher, normally toxic, challenge dose of H2O2 delivered 24 h later (26, 30). Without pretreatment with a mild dose of H2O2, the challenge dose causes protein oxidation, growth arrest, diminished DNA and protein synthesis, and some degree of apoptosis; all these measures of toxicity are avoided or minimized if cells are adapted by pretreatment with a mild dose of H2O2 before being exposed to the challenge dose (26, 29–31, 55). We now wanted to test if adaptive resistance to H2O2 toxicity could be achieved by pretreatment with a wide range of Nrf2 inducers (both oxidative and non-oxidative). In other words, we wanted to test whether adaptive increases in oxidative stress resistance, via increased proteasomal capacity, is a general feature of the Nrf2 signal transduction pathway. As shown in Fig. 6A, 1.0 mm H2O2 challenge caused a 65% decrease in cell counts in non-adapted, naive cells; this was mostly due to prolonged growth arrest, as previously shown (26, 29–31, 55). In contrast, cells that had been pretreated with (low concentrations of) a range of oxidants exhibited substantially less toxicity: only a 29% growth arrest with H2O2 pretreatment, 37% with paraquat, 42% with menadione, and 50% with peroxynitrite (Fig. 6A). We also tested other inducers of Nrf2, including dl-sulforaphane (56–58), curcumin (59–62), and lipoic acid (63–65). Growth arrest induced by H2O2 challenge was decreased (from 65%) to 39% with dl-sulforaphane pretreatment, to 31% with curcumin pretreatment, and to only 35% with lipoic acid pretreatment (Fig. 6A). Although it is important to note that these agents are not exclusive inducers Nrf2, the fact that all produced protective effects provides additional support for an important role for Nrf2 in oxidative stress adaptation.

FIGURE 6.

Pretreatment with Nrf2 inducers causes increased tolerance to oxidative stress. A, pretreatment of cells with a mild, nontoxic, dose of a range of oxidants, and other inducers of Nrf2, causes increased tolerance to a subsequent toxic H2O2 challenge. MEF cells were grown to 10% confluence and treated with 1 nm peroxynitrite, 1 nm menadione, 10 pm dl-sulforaphane, 1 pm paraquat, 500 pm curcumin, 100 nm H2O2, or 500 pm lipoic acid for 1 h, then washed and resuspended (see ”Experimental Procedures“). After 24 h, cells were challenged with 1 mm H2O2 for 1 h, then washed and resuspended. After another 24 h, cells were harvested and counted. Values are mean ± S.E., n = 3. B, the increase in tolerance to H2O2 challenge induced by mild oxidant pretreatment is lost by blocking Nrf2 expression. MEF cells were grown, and treated with siRNA directed against Nrf2 or a scrambled vector, then pretreated (or not) with 1 μm H2O2 as described in the legend to Fig. 3. After 24 h, cells were challenged with 1 mm H2O2 for 1 h, then washed and resuspended in fresh complete medium. After another 24 h, cells were harvested and cell counts were taken. Values are plotted as a percent of unchallenged samples treated with scrambled siRNA, and values are mean ± S.E., n = 4.

Nrf2, 20 S Proteasome, Pa28αβ, and Immunoproteasome Play Important Roles in H2O2-induced Adaptive Increase in Oxidative Stress Tolerance

The 20 S proteasome, immunoproteasome, and the Pa28αβ regulator all seem to play important roles in adaptation (26). We now confirmed this conclusion, using siRNA directed against the 20 S proteasome, immunoproteasome, and Pa28αβ regulator. With H2O2 challenge there was a 55% decrease in cell growth; this was reduced to only a 30% decrease with H2O2 pretreatment and adaptation (Fig. 5A). However, if cells were first pretreated with siRNA against 20 S proteasome, immunoproteasome, or Pa28αβ, the adaptive response was severely blunted and the H2O2 challenge-induced growth arrest returned to 50–60% (Fig. 5A). Having shown that Nrf2 plays a key regulatory role in H2O2-induced increases in 20 S proteasome and Pa28αβ (Fig. 4) we were interested in testing if the adaptive role of these proteins in increasing tolerance to H2O2 challenge is also Nrf2 dependent. Using the “pretreatment and challenge model” there was a shift from 65% growth arrest to only 35% growth arrest with H2O2 pretreatment; this returned to 67% growth arrest if cells were pretreated with Nrf2 siRNA (Fig. 6B), indicating a significant role for Nrf2 in H2O2-induced tolerance to oxidative stress.

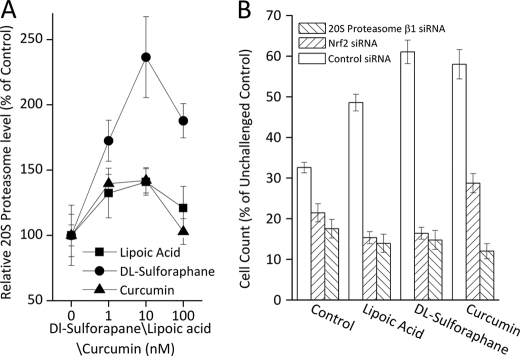

Nrf2 and Proteasome Are Key Factors in Adaptive Increase in Tolerance to Oxidative Stress Produced by Nrf2 Inducers

Having observed an adaptive response with the use of multiple Nrf2 inducers we wanted to determine whether proteasome and the Pa28αβ regulator are always involved in Nrf2-dependent adaptation. To test this we performed Western blots on cells 24 h after pretreatment with a range of concentrations of various Nrf2 inducers. We observed modest increases (≈40%) in 20 S proteasome with lipoic acid and curcumin treatment, and more than a 2-fold increase with dl-sulforaphane (Fig. 7A). To test the role of both Nrf2 and proteasome in the adaptive response to Nrf2 inducers we used the pretreatment and challenge model of Fig. 6, with a background of scrambled siRNA, Nrf2 siRNA, or 20 S proteasome siRNA (Fig. 7B). With H2O2 challenge of non-adapted cells there was a 68% growth arrest. Lipoic acid pretreatment reduced growth arrest to ≈50%; however, growth arrest returned to ≈85% with either Nrf2 or 20 S proteasome siRNA treatment. Similarly, dl-sulforaphane treatment reduced growth arrest to ≈40%, which was returned to ≈85% with either Nrf2 or 20 S proteasome siRNA treatment. Curcumin treatment reduced growth arrest to ≈40%, which was restored to ≈85% with 20 S proteasome siRNA and 70% with Nrf2 siRNA (Fig. 7B).

FIGURE 7.

Lipoic acid, dl-sulforaphane, and curcumin promote adaptation in an Nrf2 and proteasome-dependent manner. A, MEF cells were grown to 10% confluence and treated with 1–100 nm lipoic acid, 1–100 nm dl-sulforaphane, or 1–100 nm curcumin. After 24 h, cells were harvested, lysed, run on SDS-PAGE gels, and transferred to PVDF membranes as described in the legend to Fig. 2. Membranes were treated with antibodies directed against 20 S proteasome subunit β1, immunoproteasome subunit β1i (LMP2), proteasome regulator subunit PA28α, and β-tubulin. B, the adaptive response produced by Nrf2 inducers is lost or blunted by blocking either Nrf2 or proteasome expression. MEF cells were grown and pretreated with siRNA directed against Nrf2, 20 S proteasome subunit β1, or a scrambled vector then, 4 h later, treated with 500 pm lipoic acid, 10 pm dl-sulforaphane, or 500 pm curcumin, as described in the legend to Fig. 6. After 24 h, cells were challenged with 1 mm H2O2 for 1 h, then washed and resuspended in fresh complete medium. After another 24 h, cells were harvested and cell counts were taken. Values are mean ± S.E., n = 4, plotted as a percent of unchallenged samples treated with scrambled siRNA.

DISCUSSION

Our studies reveal a mechanistic link between Nrf2, the 20 S proteasome, the Pa28αβ (11 S) proteasome regulator, and transient adaptation to oxidative stress. It now appears clear that the Nrf2 signal transduction pathway plays a major role in both the increased proteasomal capacity to degrade oxidized proteins, and the increased cellular tolerance to oxidative stress that are induced by pretreatment with a mild dose of oxidant.

We find that the cellular capacity to degrade oxidized proteins, and intracellular levels of the 20 S proteasome, immunoproteasome, and the Pa28αβ (11 S) regulator are all increased 2–3-fold during adaptation to oxidative stress. Similar results were obtained with the H2O2 and peroxynitrite oxidants, and the redox-cycling agents menadione and paraquat. Proteasome inhibitors, and siRNA directed against the 20 S proteasome β1 subunit, the immunoproteasome β1i (LMP2) subunit, or the Pa28α (11 S) regulator subunit, all significantly limit the increase in cellular proteolytic capacity and partially prevented the increased resistance to oxidative stress (cell growth).

Cellular levels of Nrf2 were significantly increased by adaptation to oxidative stress, and Nrf2 was seen to translocate to the nucleus, and to bind to ARE/EpRE sequence(s) upstream of the proteasome β5 subunit gene. Blocking the induction of Nrf2, with siRNA or retinoic acid, significantly limited the adaptive increases in cellular proteolytic capacity, 20 S proteasome, and the Pa28αβ regulator. Increases in the immunoproteasome, however, were only partially blocked by Nrf2 siRNA. Blocking Nrf2 induction also limited the increase in oxidative stress resistance (cell growth). When, instead of using oxidant exposure, we pretreated cells with Nrf2 inducers lipoic acid, curcumin, or sulforaphane, we observed an increased cellular proteolytic capacity, increased 20 S proteasome, and increased cellular resistance to oxidative stress (cell growth); both Nrf2 siRNA and 20 S proteasome β1 subunit siRNA effectively blocked these increases.

These results suggest that oxidants, redox cycling agents, and other Nrf2 inducers cause adaptation through the up-regulation of Nrf2 and its translocation to the nucleus. This, in turn, induces expression of the 20 S proteasome and the Pa28αβ regulator. In contrast, the immunoproteasome, whose levels were also increased by adaptation to oxidative stress, appears to be only partially regulated by Nrf2, if at all.

The Nrf2 signal transduction pathway is known to respond to stressful conditions (37–46, 66). Under non-stress conditions Nrf2 is retained in the cytoplasm through the formation of a complex with several proteins, including Keap1. In this state it is constantly turned over through ubiquitin-dependant 26 S proteasome degradation. This permits a high expression rate, enabling rapid accumulation of Nrf2 when degradation is blocked, whereas ensuring low Nrf2 steady-state levels under normal conditions. Pretreatment with an oxidant, or other Nrf2 inducer, liberates Nrf2 from the Keap1 complex. This also prevents further Nrf2 degradation resulting in a dramatic rise in Nrf2 cellular levels as well as its translocation to the nucleus. Once there, it can bind to AREs, which have also been called EpREs, in a range of genes.

We find that genes encoding many 20 S proteasome subunits contain at least one if not multiple ARE/EpRE sequences in their upstream, untranslated regions (Fig. 5B) and have shown that at least some of these ARE/EpRE sequences have a strong increase in Nrf2 binding under H2O2 exposure. In contrast, we find that only a single subunit of the three immunoproteasome subunits contains the ARE/EpRE sequence. It is tempting to suggest that this difference in density of ARE/EpRE sequences may explain the differential sensitivity of the 20 S proteasome and the immunoproteasome to Nrf2 siRNA and retinoic acid, and to propose that immunoproteasome may be regulated by another mechanism.

Nrf2 is not the only protein that can bind to ARE/EpRE sequences, and it is certainly possible that other signal transduction proteins may bind to proteasomal and Pa28αβ (11 S) regulator ARE/EpRE elements, and/or to immunoproteasome. We are also searching for other potential pathways for immunoproteasome induction, of which the interferon regulatory factor 1 (67–69) appears to be a good candidate. Finally, there may well be overlapping pathways of signal transduction that act synergistically, or antagonistically, to dynamically adjust proteasome/immunoproteasome levels during adaptation to oxidative stress.

In conclusion, we find that increases in 20 S proteasome and Pa28αβ (11 S) regulator expression are largely mediated by the Nrf2 signal transduction pathway during adaptation to oxidative stress. These Nrf2-dependent increases in 20 S proteasome and Pa28αβ (11 S) are shown to be important for fully effective adaptive increases in cellular stress resistance. In contrast, the immunoproteasome, which also contributes to oxidative stress adaptation, is shown to be minimally responsive to Nrf2 control.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants RO1-ES003598 and ARRA Supplement 3RO1-ES 003598-22S2 from the NIEHS (to K. J. A. D.).

- Nrf2

- nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2

- PA28αβ

- proteasome activator 28 αβ

- ARE

- antioxidant response element

- EpRE

- electrophile response element

- AMC

- 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin

- Suc-LLVY-AMC

- N-succinyl-leucine-leucine-valine-tyrosine-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin.

REFERENCES

- 1. Davies K. J. (1986) Intracellular proteolytic systems may function as secondary antioxidant defenses. An hypothesis. J. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2, 155–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Davies K. J., Goldberg A. L. (1987) Proteins damaged by oxygen radicals are rapidly degraded in extracts of red blood cells. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 8227–8234 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pacifici R. E., Kono Y., Davies K. J. (1993) Hydrophobicity as the signal for selective degradation of hydroxyl radical-modified hemoglobin by the multicatalytic proteinase complex, proteasome. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 15405–15411 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Grune T., Reinheckel T., Davies K. J. (1996) Degradation of oxidized proteins in K562 human hematopoietic cells by proteasome. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 15504–15509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ullrich O., Reinheckel T., Sitte N., Hass R., Grune T., Davies K. J. (1999) Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activates nuclear proteasome to degrade oxidatively damaged histones. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 6223–6228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Davies K. J. (2001) Degradation of oxidized proteins by the 20 S proteasome. Biochimie 83, 301–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bota D. A., Davies K. J. (2002) Lon protease preferentially degrades oxidized mitochondrial aconitase by an ATP-stimulated mechanism. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 674–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bota D. A., Ngo J. K., Davies K. J. (2005) Down-regulation of the human Lon protease impairs mitochondrial structure and function and causes cell death. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 38, 665–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bulteau A. L., Lundberg K. C., Ikeda-Saito M., Isaya G., Szweda L. I. (2005) Reversible redox-dependent modulation of mitochondrial aconitase and proteolytic activity during in vivo cardiac ischemia/reperfusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 5987–5991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bulteau A. L., Szweda L. I., Friguet B. (2006) Mitochondrial protein oxidation and degradation in response to oxidative stress and aging. Exp. Gerontol. 41, 653–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chondrogianni N., Stratford F. L., Trougakos I. P., Friguet B., Rivett A. J., Gonos E. S. (2003) Central role of the proteasome in senescence and survival of human fibroblasts. Induction of a senescence-like phenotype upon its inhibition and resistance to stress upon its activation. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 28026–28037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fucci L., Oliver C. N., Coon M. J., Stadtman E. R. (1983) Inactivation of key metabolic enzymes by mixed-function oxidation reactions. Possible implication in protein turnover and ageing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 80, 1521–1525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Keller J. N., Schmitt F. A., Scheff S. W., Ding Q., Chen Q., Butterfield D. A., Markesbery W. R. (2005) Evidence of increased oxidative damage in subjects with mild cognitive impairment. Neurology 64, 1152–1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shang F., Taylor A. (1995) Oxidative stress and recovery from oxidative stress are associated with altered ubiquitin conjugating and proteolytic activities in bovine lens epithelial cells. Biochem. J. 307, 297–303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shringarpure R., Grune T., Mehlhase J., Davies K. J. (2003) Ubiquitin conjugation is not required for the degradation of oxidized proteins by proteasome. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 311–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Whittier J. E., Xiong Y., Rechsteiner M. C., Squier T. C. (2004) Hsp90 enhances degradation of oxidized calmodulin by the 20 S proteasome. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 46135–46142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pacifici R. E., Davies K. J. (1991) Protein, lipid, and DNA repair systems in oxidative stress. The free-radical theory of aging revisited. Gerontology 37, 166–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Taylor A., Davies K. J. (1987) Protein oxidation and loss of protease activity may lead to cataract formation in the aged lens. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 3, 371–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Davies K. J. (1993) Protein modification by oxidants and the role of proteolytic enzymes. Biochem. Soc Trans 21, 346–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stadtman E. R. (1986) Oxidation of proteins by mined-function oxidation systems: implication in protein turnover, ageing and neutrophil function. Trends Biochem. Sci. 11, 11–12 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Starke-Reed P. E., Oliver C. N. (1989) Protein oxidation and proteolysis during aging and oxidative stress. Arch. Biochem. Biophys 275, 559–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Conconi M., Szweda L. I., Levine R. L., Stadtman E. R., Friguet B. (1996) Age-related decline of rat liver multicatalytic proteinase activity and protection from oxidative inactivation by heat-shock protein 90. Arch. Biochem. Biophys 331, 232–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wolff S. P., Dean R. T. (1986) Fragmentation of proteins by free radicals and its effect on their susceptibility to enzymic hydrolysis. Biochem. J. 234, 399–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ding Q., Dimayuga E., Markesbery W. R., Keller J. N. (2004) Proteasome inhibition increases DNA and RNA oxidation in astrocyte and neuron cultures. J. Neurochem. 91, 1211–1218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ahn K., Erlander M., Leturcq D., Peterson P. A., Früh K., Yang Y. (1996) In vivo characterization of the proteasome regulator PA28. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 18237–18242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pickering A. M., Koop A. L., Teoh C. Y., Ermak G., Grune T., Davies K. J. (2010) The immunoproteasome, the 20 S proteasome, and the PA28αβ proteasome regulator are oxidative-stress-adaptive proteolytic complexes. Biochem. J. 432, 585–594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Teoh C. Y., Davies K. J. (2004) Potential roles of protein oxidation and the immunoproteasome in MHC class I antigen presentation. The ”PrOxI“ hypothesis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 423, 88–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ngo J. K., Davies K. J. (2009) Mitochondrial Lon protease is a human stress protein. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 46, 1042–1048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Davies K. J. (2000) Oxidative stress, antioxidant defenses, and damage removal, repair, and replacement systems. IUBMB Life 50, 279–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wiese A. G., Pacifici R. E., Davies K. J. (1995) Transient adaptation of oxidative stress in mammalian cells. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 318, 231–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ermak G., Harris C. D., Davies K. J. (2002) The DSCR1 (Adapt78) isoform 1 protein calcipressin 1 inhibits calcineurin and protects against acute calcium-mediated stress damage, including transient oxidative stress. FASEB J. 16, 814–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ferrington D. A., Husom A. D., Thompson L. V. (2005) Altered proteasome structure, function, and oxidation in aged muscle. FASEB J. 19, 644–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ferrington D. A., Hussong S. A., Roehrich H., Kapphahn R. J., Kavanaugh S. M., Heuss N. D., Gregerson D. S. (2008) Immunoproteasome responds to injury in the retina and brain. J. Neurochem. 106, 158–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Husom A. D., Peters E. A., Kolling E. A., Fugere N. A., Thompson L. V., Ferrington D. A. (2004) Altered proteasome function and subunit composition in aged muscle. Arch. Biochem. Biophys 421, 67–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kotamraju S., Matalon S., Matsunaga T., Shang T., Hickman-Davis J. M., Kalyanaraman B. (2006) Up-regulation of immunoproteasomes by nitric oxide. Potential antioxidative mechanism in endothelial cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 40, 1034–1044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yamano T., Murata S., Shimbara N., Tanaka N., Chiba T., Tanaka K., Yui K., Udono H. (2002) Two distinct pathways mediated by PA28 and hsp90 in major histocompatibility complex class I antigen processing. J. Exp. Med. 196, 185–196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rushmore T. H., Morton M. R., Pickett C. B. (1991) The antioxidant responsive element. Activation by oxidative stress and identification of the DNA consensus sequence required for functional activity. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 11632–11639 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. McMahon M., Itoh K., Yamamoto M., Chanas S. A., Henderson C. J., McLellan L. I., Wolf C. R., Cavin C., Hayes J. D. (2001) The Cap”n“Collar basic leucine zipper transcription factor Nrf2 (NF-E2 p45-related factor 2) controls both constitutive and inducible expression of intestinal detoxification and glutathione biosynthetic enzymes. Cancer Res. 61, 3299–3307 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Itoh K., Chiba T., Takahashi S., Ishii T., Igarashi K., Katoh Y., Oyake T., Hayashi N., Satoh K., Hatayama I., Yamamoto M., Nabeshima Y. (1997) An Nrf2/small Maf heterodimer mediates the induction of phase II detoxifying enzyme genes through antioxidant response elements. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 236, 313–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Itoh K., Wakabayashi N., Katoh Y., Ishii T., O'Connor T., Yamamoto M. (2003) Keap1 regulates both cytoplasmic-nuclear shuttling and degradation of Nrf2 in response to electrophiles. Genes Cells 8, 379–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nguyen T., Sherratt P. J., Pickett C. B. (2003) Regulatory mechanisms controlling gene expression mediated by the antioxidant response element. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 43, 233–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Venugopal R., Jaiswal A. K. (1996) Nrf1 and Nrf2 positively and c-Fos and Fra1 negatively regulate the human antioxidant response element-mediated expression of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase1 gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 14960–14965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Moi P., Chan K., Asunis I., Cao A., Kan Y. W. (1994) Isolation of NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), a NF-E2-like basic leucine zipper transcriptional activator that binds to the tandem NF-E2/AP1 repeat of the β-globin locus control region. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 9926–9930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kwak M. K., Wakabayashi N., Greenlaw J. L., Yamamoto M., Kensler T. W. (2003) Antioxidants enhance mammalian proteasome expression through the Keap1-Nrf2 signaling pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 8786–8794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Itoh K., Wakabayashi N., Katoh Y., Ishii T., Igarashi K., Engel J. D., Yamamoto M. (1999) Keap1 represses nuclear activation of antioxidant responsive elements by Nrf2 through binding to the amino-terminal Neh2 domain. Genes Dev. 13, 76–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. McMahon M., Itoh K., Yamamoto M., Hayes J. D. (2003) Keap1-dependent proteasomal degradation of transcription factor Nrf2 contributes to the negative regulation of antioxidant response element-driven gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 21592–21600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhang H., Forman H. J. (2008) Acrolein induces heme oxygenase-1 through PKC-δ and PI3K in human bronchial epithelial cells. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 38, 483–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ramos-Gomez M., Kwak M. K., Dolan P. M., Itoh K., Yamamoto M., Talalay P., Kensler T. W. (2001) Sensitivity to carcinogenesis is increased and chemoprotective efficacy of enzyme inducers is lost in Nrf2 transcription factor-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 3410–3415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Enomoto A., Itoh K., Nagayoshi E., Haruta J., Kimura T., O'Connor T., Harada T., Yamamoto M. (2001) High sensitivity of Nrf2 knockout mice to acetaminophen hepatotoxicity associated with decreased expression of ARE-regulated drug metabolizing enzymes and antioxidant genes. Toxicol. Sci. 59, 169–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jentoft N., Dearborn D. G. (1979) Labeling of proteins by reductive methylation using sodium cyanoborohydride. J. Biol. Chem. 254, 4359–4365 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Reinheckel T., Grune T., Davies K. J. (2000) The measurement of protein degradation in response to oxidative stress. Methods Mol. Biol. 99, 49–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wang X. J., Hayes J. D., Henderson C. J., Wolf C. R. (2007) Identification of retinoic acid as an inhibitor of transcription factor Nrf2 through activation of retinoic acid receptor α. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 19589–19594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kotamraju S., Tampo Y., Keszler A., Chitambar C. R., Joseph J., Haas A. L., Kalyanaraman B. (2003) Nitric oxide inhibits H2O2-induced transferrin receptor-dependent apoptosis in endothelial cells. Role of ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 10653–10658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Thomas S., Kotamraju S., Zielonka J., Harder D. R., Kalyanaraman B. (2007) Hydrogen peroxide induces nitric oxide and proteosome activity in endothelial cells. A bell-shaped signaling response. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 42, 1049–1061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Davies K. J. (1999) The broad spectrum of responses to oxidants in proliferating cells. A new paradigm for oxidative stress. IUBMB Life 48, 41–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kamanna V. S., Saied S. I., Evans-Hexdall L., Kirschenbaum M. A. (1991) Cholesterol esterase in preglomerular microvessels from normal and cholesterol-fed rabbits. Am. J. Physiol. 261, F163–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mandal M. N., Patlolla J. M., Zheng L., Agbaga M. P., Tran J. T., Wicker L., Kasus-Jacobi A., Elliott M. H., Rao C. V., Anderson R. E. (2009) Curcumin protects retinal cells from light-and oxidant stress-induced cell death. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 46, 672–679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yang C., Zhang X., Fan H., Liu Y. (2009) Curcumin up-regulates transcription factor Nrf2, HO-1 expression, and protects rat brains against focal ischemia. Brain Res. 1282, 133–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Nair S., Barve A., Khor T. O., Shen G. X., Lin W., Chan J. Y., Cai L., Kong A. N. (2010) Regulation of Nrf2- and AP-1-mediated gene expression by epigallocatechin-3-gallate and sulforaphane in prostate of Nrf2-knockout or C57BL/6J mice and PC-3 AP-1 human prostate cancer cells. Acta. Pharmacol. Sin. 31, 1223–1240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gan N., Mi L., Sun X., Dai G., Chung F. L., Song L. (2010) Sulforaphane protects microcystin-LR-induced toxicity through activation of the Nrf2-mediated defensive response. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 247, 129–137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Zhao H. D., Zhang F., Shen G., Li Y. B., Li Y. H., Jing H. R., Ma L. F., Yao J. H., Tian X. F. (2010) Sulforaphane protects liver injury induced by intestinal ischemia reperfusion through Nrf2-ARE pathway. World J. Gastroenterol. 16, 3002–3010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lii C. K., Liu K. L., Cheng Y. P., Lin A. H., Chen H. W., Tsai C. W. (2010) Sulforaphane and α-lipoic acid up-regulate the expression of the π class of glutathione S-transferase through c-jun and Nrf2 activation. J. Nutr. 140, 885–892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Shenvi S. V., Smith E. J., Hagen T. M. (2009) Transcriptional regulation of rat γ-glutamate cysteine ligase catalytic subunit gene is mediated through a distal antioxidant response element. Pharmacol. Res. 60, 229–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Shay K. P., Moreau R. F., Smith E. J., Smith A. R., Hagen T. M. (2009) α-Lipoic acid as a dietary supplement. Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1790, 1149–1160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Suh J. H., Shenvi S. V., Dixon B. M., Liu H., Jaiswal A. K., Liu R. M., Hagen T. M. (2004) Decline in transcriptional activity of Nrf2 causes age-related loss of glutathione synthesis, which is reversible with lipoic acid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 3381–3386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kraft D. C., Deocaris C. C., Wadhwa R., Rattan S. I. (2006) Preincubation with the proteasome inhibitor MG-132 enhances proteasome activity via the Nrf2 transcription factor in aging human skin fibroblasts. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1067, 420–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Seifert U., Bialy L. P., Ebstein F., Bech-Otschir D., Voigt A., Schröter F., Prozorovski T., Lange N., Steffen J., Rieger M., Kuckelkorn U., Aktas O., Kloetzel P. M., Krüger E. (2010) Immunoproteasomes preserve protein homeostasis upon interferon-induced oxidative stress. Cell 142, 613–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Foss G. S., Prydz H. (1999) Interferon regulatory factor 1 mediates the interferon-γ induction of the human immunoproteasome subunit multicatalytic endopeptidase complex-like 1. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 35196–35202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Namiki S., Nakamura T., Oshima S., Yamazaki M., Sekine Y., Tsuchiya K., Okamoto R., Kanai T., Watanabe M. (2005) IRF-1 mediates up-regulation of LMP7 by IFN-γ and concerted expression of immunosubunits of the proteasome. FEBS Lett. 579, 2781–2787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]