Abstract

Despite the massive toll in human suffering imparted by degenerative lung disease, including COPD, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and ARDS, the scientific community has been surprisingly agnostic regarding the potential of lung tissue and, in particular, the alveoli, to regenerate. However, there is circumstantial evidence in humans and direct evidence in mice that ARDS triggers robust regeneration of lung tissue rather than irreversible fibrosis. The stem cells responsible for this remarkable regenerative process has garnered tremendous attention, most recently yielding a defined set of cloned human airway stem cells marked by p63 expression but with distinct commitment to differentiated cell types typical of the upper or lower airways, the latter of which include alveoli-like structures in vitro and in vivo. These recent advances in lung regeneration and distal airway stem cells and the potential of associated soluble factors in regeneration must be harnessed for therapeutic options in chronic lung disease.

Key words: ARDs, lung regeneration, lung stem cells, influenza, COPD, pulmonary fibrosis

Introduction

The US Centers for Disease Control announced in 2007 that chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD), idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and acute respiratory damage syndrome (ARDS) together represent the third largest killer after heart disease and cancer and affect 24 million Americans and 600 million individuals worldwide.1,2 COPD and IPF describe the incremental development of processes of chronic bronchitis, emphysema and the scarring of terminal bronchioles and alveolar oxygen exchange surfaces. COPD itself seems to be an enhanced inflammatory response to particles in pollutants and tobacco smoke and is defined as coughing bouts with sputum production on most days for at least three months in the year over two years. Patients can be stratified as presenting primarily with bronchitis or primarily emphysema but often have features of both.3 The bronchi of COPD patients undergo a remodeling similar to asthma, including hyperplasia and hypertrophy of goblet cells and infiltration by immune cells, but also have focal evidence of squamous cell metaplasia and fibrosis. Unlike asthma, which tends to wax and wane, the chronic bronchitis in COPD shows a stalwart progression, and the severity of this bronchitis alone is sufficient to restrict airflow and induce hypoxia. Emphysema in COPD patients is a more distal airway disease that affects the bronchioles and/or alveoli in different ways and ultimately results in their progressive inactivation or collapse that, in turn, progressively limits the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide. Hyperinflation or collapse of the terminal bronchioles and alveoli result in an overall loss of elasticity of the lungs, which, in turn, compromises overall air exchange in the lungs already stressed by defects in the exchange surfaces. IPF, in contrast to COPD, presents with a dry cough and primarily affects distal, interstitial lung in which alveoli become increasingly converted to scar tissue.4 An array of exposures have been linking to pulmonary fibrosis, including asbestos, silica, certain chemotherapeutics, such as bleomycin, and radiation therapy for lung tumors. Autoimmune connective tissue disorders such as system lupus erythematosus and scleroderma can also present with lung fibrosis. However, most cases of pulmonary fibrosis have no obvious causal link and are bundled together as IPF, which shares similar histological appearance of connective tissue depositions and similar inexorable decline in pulmonary function. While both COPD and IPF appear tightly linked to aberrant inflammation, treatments using anti-inflammatory drugs, including corticosteroids, have been disappointing.5 The only remedy for end-stage cases of COPD and IPF is lung transplantation, though morbidity and mortality of this procedure is functionally prohibitive.

The almost imperceptible decline in pulmonary function experienced by COPD and IPF patients is in marked contrast to those with ARDS, where lung damage—particularly to alveoli—and onset of dyspnea can occur over several days and is often the result of direct lung infections or indirectly through sepsis.6–8 Inflammatory cytokines are thought to contribute to diffuse alveolar damage (DAD), in part by disrupting endothelial function at the level of the capillary-alveolar junctions, permitting breaching and or/type II cell dysfunction and loss of surfactants. Not surprisingly, ARDS linked to infectious agents is marked by a rapidly evolving inflammatory response involving neutrophils and T cells and ultimately results in wholesale destruction of alveoli with attending mortality rates of 40–50%.2 Aside from its acute onset and rapid dissolution of alveoli, ARDS is distinguished from COPD and IPF by remarkable recovery of normal pulmonary function in at least a subset of survivors. Thus, approximately 50% of ARDS survivors show near-normal ranges of spirometry and oxymeter readings by 6–12 mo following resolution of the infectious triggering event, often without evidence of fibrosis or other chronic damage to the lungs. While data at the level of histopathology level is limited in humans, the mouse models of influenza infection may offer instructive insights.9–14 In particular, mice receiving intratracheal, murine-adapted H1N1 influenza A virus show widespread infection of bronchiolar and alveolar cells within a few days followed by a broad inflammatory response and hemorrhagic edema in broad areas of intrastitial lung with complete loss of typical alveolar markers in these affected zones.15 Despite the loss 50–60% of lung parenchyma to the influenza infection, these mice survive and by three to five months have normal lung histology by all criteria gathered. These finding have important implications that will be addressed in this review. The first is that there must be adult stem cells responsible for this rapid process of lung regeneration. The second is that we must somehow use this regenerative capacity of the lung and knowledge of the stem cells involved to assemble new ways of addressing chronic lung disease for which therapeutic options are severely limited.

Who is the Lung Stem Cell?

Airway stem cells have been implicated in the pathology and progression of chronic airway diseases and yet also hold the promise of physiological and, ultimately, therapeutic repair of damage wrought by these conditions.16 Chronic airway disease is often regiospecific, with allergic rhinitis affecting the sinuses, asthma, cystic fibrosis; bronchiolitis obliterans affecting the large conducting tubes, such as the bronchi and bronchioles, and COPD, pulmonary fibrosis and pulmonary hypertension affecting the distal regions of the airways involved in oxygen exchange. A major focus of airway pathology, therefore, is to understand if and how stem cells initiate repair programs, participate in the airway epithelial remodeling seen in chronic conditions and mechanisms underlying defects in repair as in pulmonary fibrosis.

Critical for deciphering the processes of regiospecific repair and pathology is to define the extent of the airway stem cell repertoire. Is there one stem cell with the capacity to generate all airway cell types (ciliated, goblet, Clara, type I and type II pneumocytes?)17 Proponents of such a scheme would invoke multiple local stem cell “niches” that would dictate the differentiated fate of progeny of such generic stem cells. The other extreme would hold that the local adult stem cells in histologically distinct regions of the airways would be committed to yielding cells consistent with the particular region. The upper airways, including the nasal and trachiobronchial surfaces, are covered by stratified epithelium dominated by approximately 90% ciliated cells and 10% goblet cells. Together they form the components of a mucociliary transport process that prevents particles and microorganisms from reaching distal regions of the airways, including the lungs. These cells typically turn over after about 30 d and are replenished by subtending, undifferentiated p63+ cells that lie along the basement membrane. In fact, it has been known for some time that undifferentiated nasal and tracheal epithelium, which express p63, could be grown in vitro and differentiated at an air-liquid interface (ALI) and largely recapitulate upper airway epithelium, including ciliated and goblet cells.18–20 Basal cells are particularly attractive candidates, because they show high expression of the transcription factor p63, which is essential for the self-renewal of basal stem cells and regenerative growth of other stratified epithelia such as the epidermis, corneal epithelium, mammary and prostate glands and the urothelium.21–23 Basal cells expressing p63 and other markers such as cytokeratin 5 and 14 are especially abundant in the upper airways, and multiple experimental systems have revealed their stem cell properties for these regions. Populations of flow-sorted basal cells from murine trachea have been shown to repopulate denuded trachea or to proliferate as “tracheospheres” in vitro and to differentiate to ciliated and goblet cells.24–31 Thus the in vitro growth of immature epithelia, their differentiation to mature airway epithelium in long-term ALI cultures and subsequent lineage tracing in vivo of the progeny of keratin 5-expressing cells made it evident that that the p63-expresssing basal cells in the upper airway constitute the basal cells for the nasal and trachiobroncial epithelium. However, efforts to define a similar population of p63-expressing basal cells that might account for the distal, oxygen-exchange epithelium of the lung appeared stymied by several observations.31 The first was that basal cells were few and far between in the distal regions of the airways and difficult to detect in the terminal bronchioles in either humans or mice.30,32 Second, there is strong evidence that type II pneumocytes marked by surfactant protein C (SP-C) expression are progenitors of type I pneumocytes, the predominant alveolar cell responsible for gas exchange.33,34 Third, a population of bronchioalveolar stem cells (BASCs) were described in mice that had many of the properties expected of stem cells that could contribute to the regeneration of terminal bronchioles and their associated alveoli.35 BASCs arose from the analysis of K-ras-induced tumors in the airways in which a minor population of tumor cells co-stained for CC-10 and SP-C, markers of Clara cells found in bronchioles and type II alveoli cells, respectively. Significantly, similar CC-10/SP-C double-positive cells were found in the terminal bronchioles in normal tissue, where stem cells responsible for regenerating lung and bronchioles might be expected, and proved resistant to treatments such as naphthalene and bleomycin that specifically damage bronchiolar and alveolar epithelium, respectively. Not only do BASCs survive these treatments, but more tellingly, they proliferate in response to the damage these drugs wreak. BASCs were cloned and passaged on feeder cells and shown to differentiate to Clara-like and ATII-like cells in vitro. Several questions remain to generalize BASCs as stem cells for the distal components of the airways and the lung parenchyma. First, they have only been tested in a bleomycin model of lung damage, which is more a model of fibrosis than true damage and regeneration. The survival and proliferation of BASCs in response to bleomycin is encouraging, and means of lineage tracing for their dual markers during regeneration should provide needed evidence. The expression profiles of cloned, immature BASCs would probably aid in such a study as well as provide additional markers for their identification. Lastly, there is a critical need to find the human counterparts of BASCs for regenerative medicine for severe chronic lung disease. In summary, the identification of BASCs has been highly influential, and further developments should clarify their role in lung repair and homeostasis.

In a counterplay to the BASC hypothesis, a recent report has detailed efforts to identify stem cells in the human lung.36 Starting with the hypothesis that c-Kit is a marker of lung stem cells, these investigators FACS sorted human lung cells for a positive population, which was then expanded by in vitro cultivation, transduced with a GFP-lentivirus and transplanted to cyclosporine A-immunosuppressed mice whose lungs were damaged by liquid nitrogen ablation. The startling finding was that these c-Kit+ cells engraft in the damaged lung and assemble not only epithelial components of the bronchioles and alveoli, but also the vascular endothelium of the lung. Moreover, rather than having BASC-like markers, these c-Kit+ cells displayed expression of the so-called Yamanaka factors, a set of transcription factors to wit Sox2, Klf4 and Oct3/4 typically found in embryonic stem cells. In homage to Till and McCulloch,37 the investigators showed that these stem cells could be propagated through serial passaging in mice and retain their broad lung regenerative activities. This is an intriguing work that challenges the very notion of adult, organ-specific stem cells and posits instead an almost embryonic stem cell-like population with a high degree of pluripotency that handles regeneration of a wide spectrum of tissues following catastrophic damage. If true for the lung, this work would suggest that this c-Kit+ population might act in a more catholic manner to support the regeneration of tissues. These concepts remain to be tested, though, and the role of the c-Kit+ cells in lung regeneration has provoked much discussion. More information is needed on the gene expression profiles of these cells, e.g., how, in fact, they relate to embryonic stem cells or adult populations of stem cells from the epidermis, immune and nervous systems. Further studies will likely determine how similar adult stem cells involved in lung regeneration are to their remarkable counterparts in early development.

Stem Cell-Mediated Lung Regeneration Following ARDS

ARDS remains one of the most feared respiratory diseases due to its high mortality rates and yet offers unprecedented insight into mechanisms of lung regeneration. ARDS pretty much segregates 1:1 into those who succumb to the severe lung damage marked by diffuse alveolar damage and those who not only survive but recover to pre-ARDS levels of pulmonary function.2 As virulent influenza infections are one trigger for ARDS in humans, we examined mice that were infected with H1N1 influenza A viruses that had been adapted by serial passaging in mice together with our colleague Vincent Chow at the National University of Singapore.15 Prof. Chow was investigating how mouse-adapted influenza viruses responsible for human pandemics induced ARDS-like syndromes and how to mitigate their effects. As dramatic as the images were of lung damage imparted by these viruses, we were even more struck by the ability of some of these mice to completely recover from these infections. In particular, by day 11, these mouse lungs showed an immense immune response to these infections, which appeared as a massive infiltration of immune cells into regions of the lung and a wholesale elimination of the infected cells, including wide swatches of lung tissue. The mice at this time underwent considerable weight loss but survived the sub-LD50 dose of virus, recovered overall weight and appeared remarkably normal two months later. Indeed the histology of the lungs of these surviving mice had all the morphological and immunological hallmarks of normal lung tissue despite the dire condition of these mice weeks earlier. As such, the influenza model of ARDS in mice supports the notion that the human ARDS survivors, in fact, achieve their normal pulmonary function not through adaptation but rather de novo generation of alveoli structures. The histology of the lungs of the recovered mice was a turning point in our work, as up to then, we only had bleomycin and radiation to impart lung damage, and yet both are better models of pulmonary fibrosis rather than regeneration.38 The influenza-induced ARDS was thus a model of lung regeneration that essentially demanded the presence of a robust set of stem cells to achieve this end.

Faced with this intriguing model of lung regeneration following fulminant influenza infections, there had to be somewhere robust signatures of stem cell activity. The histology was not terribly helpful, as by day 11 post-infection, the lung appeared as a chaotic jumble of hemorrhage, immune cell infiltrates and cellular debris. Perhaps the infected lung cells first had to be cleared by neutrophils and macrophages before any regenerative process was initiated. It was also unclear how to identify the stem cells that we knew had to be operating at a high level. Markers for BASCs markers and c-Kit+ cells were some possibilities, as was p63, which labels the basal cells of the upper airways implicated in the regeneration of ciliated cells and goblet cells in the upper airways. At the time we started, there was no hint that p63+ cells could play any role in lung regeneration. Despite their abundance along the upper airway basement membrane, p63+ cells were rarely found in the bronchioles and never in the interstitial lung. Moreover, regardless of ongoing lineage-tracing analyses of the co-expressed marker keratin 5 following bleomycin-induced lung damage, there had never been reports of keratin 5 cells in any lung repair process.30,32 However, our lab had worked extensively on the role of p63 in stratified epithelia, and had published evidence in support of the notion that p63 in fact is the “master” regulator of self-renewal of all stratified epithelia, including the epidermis, mammary and prostate glands and the airways.23 We also were aware that bleomycin, the drug of choice for lung damage in mice, may only yield fibrosis rather than true regeneration, and this might explain why regeneration and the stem cells underlying this process had not been observed. For these reasons, Pooja Ashok Kumar, a graduate student in the lab probed influenza-infected lungs with antibodies to p63. The results were striking: whereas there are no p63 cells present in the lung of control animals and only occasionally in the bronchioles, their numbers rapidly increased within a few days of infection in the bronchioles at the same time that nearby infected Clara cells were dying off. The proliferation of these basal, p63+ cells in the bronchioles increased through day 9 of the infection, at which point they suddenly and almost synchronously moved out of the confines of the bronchioles to sites of the most severe damage in the lung parenchyma, marked by a tangle of immune cells and cell carnage. Even more dramatically, these migrating p63+ cells either assembled into or proliferated into discrete clusters of 30 or so cells that we termed “pods” based on their alien surroundings.15 The p63+/Krt5+ pods were always found in proximity to bronchioles and always appeared in regions of lung parenchyma having immune cell infiltrates (Fig. 1). Significantly, the p63/Krt5+ pods at day 11 appeared as tight, solid droplets of cells, while over the next two weeks, these pods expanded to roughly to the size of alveoli and simultaneously developed a hollow lumen. In the course of this expansion, the pods began to express the type I pneumocyte marker PDPD as well as lung-specific antigens recognized by the 11B6 and 1H8 monoclonal antibodies that Dakai Mu and Yan Sun developed in the lab (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Association of Krt5 pods with influenza-damaged lung. Left: Histological appearance of lung at 21 d post-influenza showing normal appearing tissue together with regions of damage and dense immune cell infiltrates. Right: Krt5 immunohistochemistry revealing Krt5 pods in interstitial regions marked by less dense infiltrates.

Figure 2.

Expression of alveolar antigen in Krt5 pods at 15 d post-infection. Left: Distribution of antigen recognized by 1H8 monoclonal antibody in normal lung. Right: Co-staining of Krt5 and 1H8 monoclonal antibody in lung at 15 d post-influenza infection.

This massive expansion of p63 cells in the bronchioles and their precipitous migration to sites of influenza-mediated lung damage was such that we could observe, even in western blots of whole distal lung tissue, a clear accumulation of p63 protein. We therefore reasoned that we could employ Howard Green's irradiated 3T3 feeder cells to quantify the increase in p63+ cells. Green and colleagues showed, in a dramatic series of experiments, that 3T3 cells could be used to selectively grow colonies of rare stem cells from a total population of epidermal cells.39,40 With similar methods, distal lung of control animals indeed displayed very few clonogenic cells, and these expressed p63 and keratin 5, consistent with other stem cells of stratified epithelia. In stark contrast, however, the distal lungs of mice infected with H1N1 influenza showed a several hundred-fold increase in clonogenic cells, and these too expressed p63 and keratin 5. Thus this clonogenic assay confirmed what we had suspected from the histological analysis of the infected lungs—that p63+/Krt5+ cells underwent a major expansion in response to influenza-induced ARDS in these mice. Then Pooja together with Yusuke Yamamoto, a postdoctoral fellow in the lab, performed whole-genome expression analyses with the clones from control and infected mice to compare their profiles. These analyses revealed the exciting discovery that clones from the infected mice showed a differential upregulation of genes linked to tissue repair. Keratin 6 was one of these upregulated genes in the clones from infected mice and is an established marker of epidermal stem cells that are migrating for wound repair.41 Interestingly, the expression of keratin 6 alone was enough to distinguish control clones from those isolated from infected lung. Keratin 6 antibodies were also very specific for p63+/krt5+ cells that had migrated out of the bronchioles to sites of interstitial lung damage from influenza infection but showed no staining of p63+Krt5+ cells that remained in the bronchioles. These data support a general notion that the emergent p63/Krt5 cells in the lung are the response to signals of damage in a process of wound repair not unlike those that recruit skin stem cells to sites of barrier decay or breaching. The nature of the signals that recruit stem cells for lung regeneration and coordinate this obviously complex process will occupy the next decade of research for the discovery of novel therapeutics. In a forerunner of such experiments, we next used laser capture microdissection (LCM) to carve out regions of infected lung from frozen sections that separately showed normal appearing lung, damaged lung with abundant Krt5 pods, damaged lung without Krt5 pods and damaged lung having abundant SP-C stained cells. The RNA was isolated and amplified from these different captured regions and subjected to gene expression microarrays. Significantly, there was considerable overlap in gene expression between the “normal” and the Krt5 pod-containing damaged lung, but the damaged lung and the damaged lung with SP-C+ cells were very similar to one another and quite distinct from the normal lung or regions having Krt5+ pods. Given these data, we feel that the search for secreted factors, especially in regions of lung marked by Krt5 pods and presumably undergoing repair, are paramount going forward. Initial results have highlighted several pathways, including those involving Hedgehog and the PPARγ as well as a host of secreted factors. Obviously these are early days and forays into the function and potential utility of these factors42,43 and their counterparts in human lung, and it will require patience and new strategies to tease out which are the most significant and deliverable. Significant efforts will also have to be devoted to identifying human stem cells for lung regeneration and how to marshal them for the very complex problems of chronic lung disease.

Human Stem Cells for Airway and Lung Regeneration

Despite the extensive studies on p63-expressing stem cells in the upper airways and our own findings of p63+ cells contributing to lung regeneration following ARDS in mice, it was completely unclear whether we were dealing with one p63+ airway stem cell occupying different niches or many that were committed to regiospecific differentiation. Therefore, it was important to clone human stem cells from these different regions of the respiratory system and ask what they could do upon differentiation. To do this, Yuanyu Hu, a postdoctoral fellow in the lab, again employed the methods of Green and colleagues to selectively grow stem cell colonies from a larger population of nasal tubinate, trachiobronchial and distal airway epithelial cells.15 In general, anywhere between 1:500 to 1:5,000 of these cells form immature clusters of cells on irradiated 3T3 cells that in Howard Green parlance represent “holoclones.”40 In keeping with Green's definition of holoclones, many of the passaged single cells from our clones would also give rise to holoclones. The ability to clone these airway stem cells for the first time put numerous experimental directions in easy reach. But first we wanted to establish a means of clearly understanding the features of adult stem cell commitment and multipotency, issues that are often mired in adult stem cell analyses using populations of stem cells. For instance, whole populations of immature nasal epithelial cells are often used to generate air-liquid interface cultures that dramatically differentiate to ciliated and goblet cells. At the end of the day, however, it remained unclear whether ciliated cells and goblet cells are derived from separate “ciliated cell” and “gobet cell” progenitors committed to such exact fates, or whether a single stem cell gives rise to both. While conclusions might be extrapolated from low conversion lineage tracing experiments in vivo, it was impossible to access multipotency from the analysis of populations of human counterparts in vitro. Therefore, we instituted a simple pedigree-tracking protocol, where we used cloning rings to isolate single clones of respiratory stem cells, which were derived from single cells, and expanded these to perform parallel analyses on each pedigree (Fig. 3). In this manner, we were able to examine multiple pedigrees from given regions of the respiratory system for long-term proliferation potential, whole-genome expression analysis and multiple differentiation protocols to assess multipotency. The upshot of these studies was that morphologically, the stem cells of the nasal, trachiobronchiolar and distal airways appeared identical and, in fact, not distinguishable morphologically from those of the epidermis. All showed strong expression of p63 in their nuclei and keratin 5 in their cytoplasm. All could be propagated for at least 50–60 divisions while maintaining immaturity and thus beyond the realm of so-called “transit-amplifying” cells. Almost disturbingly, the whole-genome expression profiles of these clones from different regions of the respiratory system were also very similar across 17,500 informative genes, with significant gene differences accounting for only 100–300 genes, or approximately 1% of the total. However, these minor gene differences were consistent across the pedigrees derived from the three distinct regions of the airways and provided a ray of hope that, in fact, these stem cells were unique as opposed to drones at the beck and call of local niches. But the true nature of these stem cell pedigrees was revealed when they were subjected to identical conditions of differentiation in either ALI cultures, 3D Matrigel cultures or self-assembly assays, all of which were required to tease out the respective multipotency of these pedigrees. The ALI cultures showed that while the NESC and TASC pedigrees yielded similar patterns of stratified epithelia, with immature basal cells and suprabasal ciliated and goblet cells after 20 d (Fig. 4), the DASCs yielded only a monolayer of cells with very rare ciliated cells (<1:500) and occasional CC10+ cells (<1:100). 3D Matrigel cultures of these pedigrees were extremely informative and showed that both the NESCs and the TASCs formed dense spheres of squamous cells akin to squamous cell metaplasia (Fig. 4), while the DASCs acted very differently and formed spheres of unilaminar arrays of cells not unlike those of alveoli (Fig. 5). These structures assembled from the DASCs expressed markers of type I pneumocytes such as PDPN and bound the 4C10 monoclonal antibody that was generated in the lab by Dakai Mu against human lung tissue. These data were paralleled by the analysis of rat and mouse DASCs, which also assembled into unilaminar spheres expressing antigens recognized by other monoclonal antibodies generated by Dakai that are specific to rat and mouse lung, and consistent with expression microarrays performed on the differentiated cells. Thus, the analyses of defined pedigrees of the regiospecific stem allowed a number of conclusions from relatively simple experiments. The first is that the adult stem cells of the respiratory system are distinct at the level of gene expression, albeit these differences involve a limited set of genes. Second, these stem cells are intrinsically committed to distinct fates even after multiple passaging in vitro, suggesting that this intrinsic program, rather than a particular stem cell “niche,” plays the dominant role in progeny fate determination. That being said, the finding that the NESCs and TAECs of the upper airways differentiate to ciliated and goblet cells in ALI culture but squamous metaplasia in 3D Matrigel would seem to belie the concept of differential commitment of stem cells independent of the niche. Our sense, and indeed that supported by the experimental data, is that NESCs and TASCs are committed to both respiratory epithelium and to pathologic squamous metaplasia, and the environment can tip the balance here. However, DASCs show neither of these fates presented by NESCs and TASCs in either ALI or 3D Matrigel cultures despite identical conditions and instead form unilaminar structures with expression profiles of distal airway and lung. Thus, despite the morphological and gene expression similarities between the upper airway stem cells and those of the distal airways, they clearly possess distinct programs of cell fate. A separate issue is whether NESCs and TASCs are different or rather represent a single stem cell for the whole of the upper airways from the nasal epithelium to the bronchi. The expression data sets of NESCs and TASCs show distinct although limited differences in the range of the differences between the upper and lower airway stem cells. Yet it is difficult to detect differences in cell fate in the three different assays we have employed to date, but we suspect the deficiency here is more at the level of laboratory protocols and sensitivity that fails to reveal their differences, though the jury is still out on that. But in the final analysis, the identification of distinct stem cells in the airways is of critical importance for any future schemes in regenerative medicine or testing of drugs or biologics for their ability to rally such cells. Other implications of this work include the realization that adult stem cell commitment must be dependent on a small number of genes, which if the Weintraub/Yamanaka concepts44,45 are considered, one might imagine that transcription factors among the small set of genes that distinguish TASCs from DASCs should play important roles in setting stem cell commitment.

Figure 3.

Schematic for development of stem cell pedigrees. Colonies derived from single cells are isolated and expanded for multiple, parallel analyses.

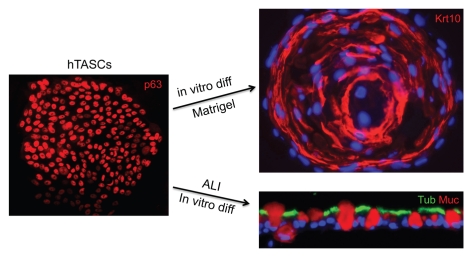

Figure 4.

TASCs show dual commitment to airway and squamous fates. Left: Single colony of defined pedigree of TASCs stained with antibodies to p63. Right: Alternative fate commitment revealed by 3D growth in Matrigel, where squamous metaplasia is revealed, vs. air-liquid interface cultures, where airway epithelia predominates.

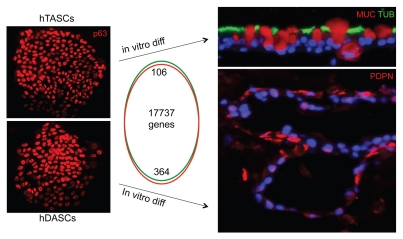

Figure 5.

Differential fate commitment of TASCs and DASCs. Left: TASCs and DASCs colonies stained with anti-p63 appear indistinguishable and show gene expression differences in only 100–300 genes of 17,000 hybridizing transcripts as depicted in Venn diagram. Right: TASCs differentiating to airway epithelia in air-liquid interface culture, whereas DASCs differentiate to unilaminar, alveoli-like structures in 3D Matrigel culture.

Therapeutic Implications of Cloned Lung Stem Cells

With the validation of lung stem cell candidates (BASCs, c-Kit ES-like cells or p63+DASCs), it will be imperative to convert this information in some fashion for treatments of acute and chronic lung conditions. For rapidly emerging conditions such as ARDS, it might be difficult to marshal a cell-based therapy in time to affect initial three-week vulnerability period. This would seem to render efforts to retrieve, propagate and install new cells beyond the window of therapeutic utility. However, therapeutic strategies based on aiding or co-opting endogenous stem cells to join in regenerative efforts must be considered. We think the only viable direction here with acute lung damage is to identify the secreted factors that normally alert these endogenous stem cells to proliferate, migrate to sites of damage or assemble alveoli and associated capillary networks and employ these as biologics. While candidate secreted factors have been identified, these data sets need to be expanded, combined with others derived from different models of lung regeneration and tested in quantitative models for efficacy. Chronic lung diseases may indeed benefit from cell-based therapies or combinations of autologous stem cell transplants and biologics-assisted activation of endogenous stem cells. However, unlike ARDS, in which lung tissue is essentially dissolved by the actions of the innate and adaptive immune responses, chronic conditions such as COPD and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis present with defective but intact terminal bronchioles and alveoli further marred by scar tissue. Strategies based on surgical abrasion, ablation or limited infection to both clear tissue and stimulate regenerative responses followed by exogenous stem cell infusion might represent extreme but rational approaches to model new lung tissue. Some of these concepts form the basis of present experiments in the laboratory with appropriate mouse models, with the sober anticipation of new challenges and barriers offset with the expectation of progress toward addressing abject lung disease affecting thousands of individuals.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the members in the Xian-McKeon laboratory for helpful discussions and support. This work was supported by the Institutes of Heart, Lung and Blood, and General Medical Sciences of the NIH (RC1 HL100767 and RO1-GM083348 and R21CA124688), the Defense Agency Research Projects Agency (DARPA; Project N66001-09-1-2121), the European Research Council and the Genome Institute of Singapore.

References

- 1.Balkissoon R, Lommatzsch S, Carolan B, Make B. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a concise review. Med Clin North Am. 2011;95:1125–1141. doi: 10.1016/j. mcna.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tansey CM, Louie M, Loeb M, Gold WL, Muller MP, de Jager J, et al. One-year outcomes and health care utilization in survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1312–1320. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.12.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burrows B, Fletcher CM, Heard BE, Jones NL, Wootliff JS. The emphysematous and bronchial types of chronic airways obstruction. A clinicopathological study of patients in London and Chicago. Lancet. 1966;1:830–835. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(66)90181-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fellrath JM, du Bois RM. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis/cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis. Clin Exp Med. 2003;3:65–83. doi: 10.1007/s10238-003-0010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walter N, Collard HR, King TE., Jr Current perspectives on the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:330–338. doi: 10.1513/pats.200602-016TK. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davidson TA, Caldwell ES, Curtis JR, Hudson LD, Steinberg KP. Reduced quality of life in survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome compared with critically ill control patients. JAMA. 1999;281:354–360. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.4.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herridge MS, Cheung AM, Tansey CM, Matte-Martyn A, Diaz-Granados N, Al-Saidi F, et al. Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. One-year outcomes in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:683–693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matuschak GM, Lechner AJ. Acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome: pathophysiology and treatment. Mo Med. 2010;107:252–258. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mori I, Komatsu T, Takeuchi K, Nakakuki K, Sudo M, Kimura Y. Viremia induced by influenza virus. Microb Pathog. 1995;19:237–244. doi: 10.1016/S0882-4010(95)90290-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gubareva LV, McCullers JA, Bethell RC, Webster RG. Characterization of influenza A/HongKong/156/97 (H5N1) virus in a mouse model and protective effect of zanamivir on H5N1 infection in mice. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1592–1596. doi: 10.1086/314515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao P, Watanabe S, Ito T, Goto H, Wells K, McGregor M, et al. Biological heterogeneity, including systemic replication in mice, of H5N1 influenza A virus isolates from humans in Hong Kong. J Virol. 1999;73:3184–3189. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.3184-3189.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu X, Tumpey TM, Morken T, Zaki SR, Cox NJ, Katz JM. A mouse model for the evaluation of pathogenesis and immunity to influenza A (H5N1) viruses isolated from humans. J Virol. 1999;73:5903–5911. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5903-5911.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belser JA, Szretter KJ, Katz JM, Tumpey TM. Use of animal models to understand the pandemic potential of highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses. Adv Virus Res. 2009;73:55–97. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(09)73002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Narasaraju T, Ng HH, Phoon MC, Chow VT. MCP-1 antibody treatment enhances damage and impedes repair of the alveolar epithelium in influenza pneumonitis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2010;42:732–743. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0423OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar PA, Hu Y, Yamamoto Y, Hoe NB, Wei TS, Mu D, et al. Distal airway stem cells yield alveoli in vitro and during lung regeneration following H1N1 influenza infection. Cell. 2011;147:525–538. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rock JR, Randell SH, Hogan BL. Airway basal stem cells: a perspective on their roles in epithelial homeostasis and remodeling. Dis Model Mech. 2010;3:545–556. doi: 10.1242/dmm.006031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mercer RR, Russell ML, Roggli VL, Crapo JD. Cell number and distribution in human and rat airways. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1994;10:613–624. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.10.6.8003339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jorissen M, Van der Schueren B, Van den Berghe H, Cassiman JJ. The preservation and regeneration of cilia on human nasal epithelial cells cultured in vitro. Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1989;246:308–314. doi: 10.1007/BF00463582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mendelsohn MG, Dilorenzo TP, Abramson AL, Steinberg BM. Retinoic acid regulates, in vitro, the two normal pathways of differentiation of human laryngeal keratinocytes. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 1991;27:137–141. doi: 10.1007/BF02630999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernacki SH, Nelson AL, Abdullah L, Sheehan JK, Harris A, Davis CW, et al. Mucin gene expression during differentiation of human airway epithelia in vitro. Muc4 and muc5b are strongly induced. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;20:595–604. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.20.4.3442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang A, Kaghad M, Wang Y, Gillett E, Fleming MD, Dötsch V, et al. p63, a p53 homolog at 3q27-29, encodes multiple products with transactivating, death-inducing, and dominant-negative activities. Mol Cell. 1998;2:305–316. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80275-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang A, Schweitzer R, Sun D, Kaghad M, Walker N, Bronson RT, et al. p63 is essential for regenerative proliferation in limb, craniofacial and epithelial development. Nature. 1999;398:714–718. doi: 10.1038/19539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Senoo M, Pinto F, Crum CP, McKeon F. p63 is essential for the proliferative potential of stem cells in stratified epithelia. Cell. 2007;129:523–536. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Avril-Delplanque A, Casal I, Castillon N, Hinnrasky J, Puchelle E, Péault B. Aquaporin-3 expression in human fetal airway epithelial progenitor cells. Stem Cells. 2005;23:992–1001. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cole BB, Smith RW, Jenkins KM, Graham BB, Reynolds PR, Reynolds SD. Tracheal Basal cells: a facultative progenitor cell pool. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:362–376. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hackett TL, Shaheen F, Johnson A, Wadsworth S, Pechkovsky DV, Jacoby DB, et al. Characterization of side population cells from human airway epithelium. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2576–2585. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hajj R, Baranek T, Le Naour R, Lesimple P, Puchelle E, Coraux C. Basal cells of the human adult airway surface epithelium retain transit-amplifying cell properties. Stem Cells. 2007;25:139–148. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hong KU, Reynolds SD, Watkins S, Fuchs E, Stripp BR. In vivo differentiation potential of tracheal basal cells: evidence for multipotent and unipotent sub-populations. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:643–649. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00155.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stripp BR, Reynolds SD. Maintenance and repair of the bronchiolar epithelium. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:328–333. doi: 10.1513/pats.200711-167DR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rock JR, Onaitis MW, Rawlins EL, Lu Y, Clark CP, Xue Y, et al. Basal cells as stem cells of the mouse trachea and human airway epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:12771–12775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906850106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rock JR, Hogan BL. Developmental biology. Branching takes nerve. Science. 2010;329:1610–1611. doi: 10.1126/science.1196016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boers JE, Ambergen AW, Thunnissen FB. Number and proliferation of basal and parabasal cells in normal human airway epithelium. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:2000–2006. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.6.9707011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Evans MJ, Cabral LJ, Stephens RJ, Freeman G. Transformation of alveolar type 2 cells to type 1 cells following exposure to NO2. Exp Mol Pathol. 1975;22:142–150. doi: 10.1016/0014-4800(75)90059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sugihara H, Toda S, Miyabara S, Fujiyama C, Yonemitsu N. Reconstruction of alveolus-like structure from alveolar type II epithelial cells in three-dimensional collagen gel matrix culture. Am J Pathol. 1993;142:783–792. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim CF, Jackson EL, Woolfenden AE, Lawrence S, Babar I, Vogel S, et al. Identification of bronchioalveolar stem cells in normal lung and lung cancer. Cell. 2005;121:823–835. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kajstura J, Rota M, Hall SR, Hosoda T, D'Amario D, Sanada F, et al. Evidence for human lung stem cells. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1795–1806. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1101324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 37.Siminovitch L, Till JE, McCulloch EA. Decline in colony-forming ability of marrow cells subjected to serial transplantation into irradiated mice. J Cell Physiol. 1964;64:23–31. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1030640104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moore BB, Hogaboam CM. Murine models of pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;294:152–160. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00313.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rheinwald JG, Green H. Serial cultivation of strains of human epidermal keratinocytes: the formation of keratinizing colonies from single cells. Cell. 1975;6:331–343. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(75)80001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barrandon Y, Green H. Three clonal types of keratinocyte with different capacities for multiplication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:2302–2306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.8.2302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wojcik SM, Bundman DS, Roop DR. Delayed wound healing in keratin 6a knockout mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:5248–5255. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.14.5248-55.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berthiaume Y, Lesur O, Dagenais A. Treatment of adult respiratory distress syndrome: plea for rescue therapy of the alveolar epithelium. Thorax. 1999;54:150–160. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.2.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ding BS, Nolan DJ, Guo P, Babazadeh AO, Cao Z, Rosenwaks Z, et al. Endothelial-derived angiocrine signals induce and sustain regenerative lung alveolarization. Cell. 2011;147:539–553. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tapscott SJ, Davis RL, Thayer MJ, Cheng PF, Weintraub H, Lassar AB. MyoD1: a nuclear phospho-protein requiring a Myc homology region to convert fibroblasts to myoblasts. Science. 1988;242:405–411. doi: 10.1126/science.3175662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]