Abstract

RB family proteins pRb, p107 and p130 have similar structures and overlapping functions, enabling cell cycle arrest and cellular senescence. pRb, but not p107 or p130, is frequently mutated in human malignancies. In human fibroblasts acutely exposed to oncogenic ras, pRb has a specific role in suppressing DNA replication, and p107 or p130 cannot compensate for the loss of this function; however, a second p53/p21-dependent checkpoint prevents escape from growth arrest. This model of oncogene-induced senescence requires the additional loss of p53/p21 to explain selection for preferential loss of pRb function in human malignancies. We asked whether similar rules apply to the role of pRb in growth arrest of human epithelial cells, the source of most cancers. In two malignant human breast cancer cell lines, we found that individual RB family proteins were sufficient for the establishment of p16-initiated senescence, and that growth arrest in G1 was not dependent on the presence of functional pRb or p53. However, senescence induction by endogenous p16 was delayed in primary normal human mammary epithelial cells with reduced pRb but not with reduced p107 or p130. Thus, under these circumstances, despite the presence of functional p53, p107 and p130 were unable to completely compensate for pRb in mediating senescence induction. We propose that early inactivation of pRb in pre-malignant breast cells can, by itself, extend proliferative lifespan, allowing acquisition of additional changes necessary for malignant transformation.

Key words: breast cancer, senescence, retinoblastoma, p130, p107

Introduction

The stable cell cycle arrest that occurs during the senescence response to a variety of stressful stimuli, including oncogene induction, DNA damage and critically short telomeres,1,2 has been shown to serve as a key impediment to the development of invasive cancers.3–5 This growth arrest is often mediated through RB family proteins (pRb, p107 and p130), which have similar structures and overlapping functions.6,7 RB family proteins are regulated by cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) 2, 4 and 6.8 When CDK activity is inhibited by the tumor suppressor p16INK4A/CDKN2A (p16), hypophosphorylated RB family proteins form complexes with E2F transcription factors, leading to cell cycle arrest.9 Despite the similarities among RB family proteins, defects in pRb, but not in p107 or p130, have been associated with several human cancers.10,11 This suggests that pRb has unique tumor suppressor properties that are not attributable to p107 or p130. In support of this concept, pRb was recently shown to be preferentially associated with E2F targets involved in DNA replication during ras-induced cellular senescence of primary human fibroblasts.12 In these experiments, suppression of pRb, but not p107 or p130, allowed continued DNA synthesis. While these results indicate a special function of pRb, manifestation of a selective growth advantage by fibroblasts lacking pRb expression also required prior inactivation of a second p53/p21-dependent checkpoint. In the current work, we asked whether pRb has non-redundant tumor suppressor functions in epithelial cells, the precursors of a majority of human cancers, and if the phenotypic consequences of pRb loss require a particular genetic background.

Results

Individual RB family proteins can compensate for each other in mediating growth arrest of human breast cancer cell lines.

To directly investigate the RB family protein requirements for p16-initiated growth arrest in human epithelial cells, we utilized two model systems. The first model employed exogenously introduced tetracycline-regulated p16 genes in MDA-MB-231 [estrogen receptor α (-), p53(-)] and MCF7 [estrogen receptor α (+), p53(+)] human breast cancer cell lines, both of which lack endogenous p16 gene function.13 We created stable sub-lines in which pRb, p107 or p130 were individually suppressed through the action of shRNA-encoding retroviruses.12 While the shR NAs each effectively reduced protein levels (Figs. 1A and S1A), none of them prevented G1 arrest when p16 was induced by the addition of doxycycline (Figs. 1B and S1B). Thus, in contrast to human fibroblasts undergoing ras-induced senescence, human breast cancer cells undergoing acute p16-induced senescence did not specifically require the presence of pRb to suppress DNA replication. In addition, extended exposure to p16 led to similar losses in colony-forming efficiency by control cells and cells in which the expression of individual RB family proteins was suppressed (Fig. 1C). Interestingly, the induction of growth arrest by p16 in cells lacking pRb expression was not dependent on the presence of functional p53, as MDA-MB-231 cells express mutated, non-functional p53.14

Figure 1.

Individual RB family proteins can compensate for each other in mediating p16-initiated growth arrest of MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells. (A) MDA-MB-231-TETp16 cells stably transduced with retroviruses encoding shRNAs against indicated RB family proteins were harvested and analyzed by immunoblotting. Prominent Ponceau S stained bands were used as loading controls. (B) Cells transduced with indicated shRNAs or vector alone were treated with 1 µM doxycycline for 48 h then harvested and subjected to propidium iodide (PI) staining and flow cytometry. Exponentially growing cells transduced with an empty vector were used as controls. (C) Cells transduced with indicated shRNAs or vector alone were treated with 1 µM doxycycline for 48 h then dissociated, counted and re-plated at clonal densities in the absence of doxycycline. After 3 weeks, the resulting colonies were counted and plating efficiency was calculated as (#colonies formed/#cells plated) × 100%. Relative plating efficiencies were then calculated by comparison to un-induced controls. Mean values and standard deviations (n = 3) are shown. (D) MDA-MB-231-TETp16 cells expressing HPV E6 or HPV E7 were either left untreated (-DOX) or treated with 1 µM doxycycline for 48 h (+DOX). The cells were then harvested, subjected to PI staining and analyzed by flow cytometry.

To investigate the possibility that p16 causes growth arrest in these cells via an RB family protein-independent pathway, we attempted to knockdown all three RB family proteins simultaneously by introducing a single vector encoding shRNAs against them.12,13 However, despite multiple rounds of infection, we were not able to efficiently suppress all three proteins in the breast cancer cell lines using this vector (data not shown). In an alternative approach, we employed human papilloma virus (HPV) oncoprotein E7, which binds and inactivates all three RB family proteins.15 HPV E7 expression partially prevented p16-initiated G1 growth arrest in MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 1D). In contrast, expression of HPV E6, which inactivates p53, but does not interact with RB family members,15 had no effect on p16-initiated G1 growth arrest. These results collectively suggest that in at least some breast cancer cells (1) RB family proteins are required for p16-initiated growth arrest, (2) individual RB family proteins are sufficient to mediate growth arrest and (3) functional p53 is not required for p16-initiated growth arrest in the presence or absence of pRb.

Suppression of pRb, but not p107 or p130, extends the proliferative lifespan of primary human mammary epithelial cells.

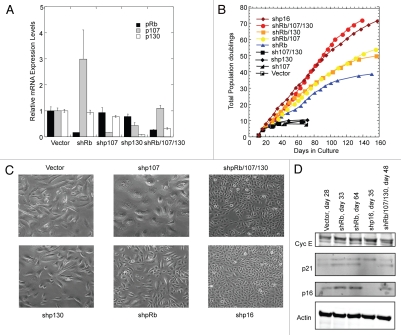

We further investigated the roles of RB family proteins using primary normal human mammary epithelial cells (HMECs) as a model. Propagation of primary HMECs in conventional adherent cultures is accompanied by spontaneous induction of endogenous p16, which leads to senescence and cessation of net population increases after approximately ten population doublings.16 Suppression of p107, p130 or both did not lead to extension of HMEC proliferative lifespan in two independent experiments using different specimens (Figs. 2A, B, S2A and B). In contrast, suppression of pRb in HMEC cultures allowed these cells to proliferate significantly longer than controls, although the shpRb-transduced HMEC cultures still ultimately underwent senescence. Combining shRNAs against p107 or p130 with those against pRb led to small additional increases in proliferative lifespans. During the prolonged proliferative phase, shpRb-transduced HMEC cultures were morphologically heterogeneous, containing mixtures of large senescent and small actively growing cells (Fig. 2C), whereas shpRb/107/130-transduced HMEC cultures proliferated rapidly without exhibiting morphological heterogeneity. The appearance and proliferation rates of the latter cells resembled those of cells expressing p16 shRNAs. Thus, although p107 and/or p130 retained some ability to compensate for pRb in mediating p16-initiated growth arrest of primary HMECs, the compensation was inefficient.

Figure 2.

Suppression of pRb, but not p107 or p130, extends the proliferative lifespan of primary human mammary epithelial cells. (A) The relative expression of mRNAs encoding pRb, p107 and p130 was measured by qRT-PCR for actively growing HMECs stably transduced with retroviruses encoding shRNAs against the indicated proteins. Quantitative results were normalized to those of a stably expressed reference transcript encoding TATA binding protein (TBP). Mean values and SD (n = 3) are shown. (B) Total population doublings of HMECs stably transduced with retroviruses encoding shRNAs against the indicated proteins are plotted vs. time. (C) Representative morphologies of HMEC cultures expressing the indicated shRNAs (200x). The micrographs were taken 30 d (Vector, shp107, shp130), 52 d (shpRb), 42 d (shpRb/107/130) or 23 d (shp16) following viral transduction. (D) Total levels of cyclin E, p21 and p16 proteins were compared by immunoblotting in HMECs transduced with indicated shRNAs. Actin abundance was used as an indication of loading equivalence. The results shown are representative of results obtained using HMECs from two independent specimens. See additional results in Figure S2.

We attempted to determine whether knocking down pRb conferred unique properties that might be responsible for the increased lifespan of shpRb-transduced HMEC cultures. In pRb-deficient fibroblasts transfected with Ras oncogenes, increased levels of cyclin E expression were linked to increased DNA replication; however, pRb loss triggered a second p53/p21-dependent checkpoint that prevented escape from senescence.12 In contrast, while we observed significantly elevated levels of both p16 and p21 CDK inhibitors in shRb-transduced HMECs, there were no corresponding increases in cyclin E levels that might compensate and thereby explain the ability of the shpRb-transduced HMECs to continue growth under these conditions (Figs. 2D and S2C). Interestingly, a faster migrating form of p21 was retained in all the shRNA-expressing HMECs with the exception of those expressing p16 shRNAs. The significance of this altered form of p21, the presence of which did not correlate with growth rate or proliferative potential, is not known but may correspond to a truncated version that lacks a nuclear localization signal in the N-terminal region of the protein.17

The different abilities of RB-family proteins to compensate for each other in breast tumor cell lines vs. HMECs are unlikely to be solely due to the levels of CDK4/6 inhibition achieved.

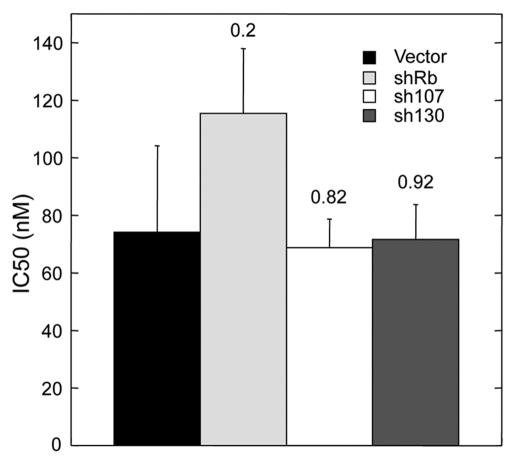

Since the canonical role of p16 is inhibition of CDK 4/6 activity, we asked whether the different abilities of RB-family proteins to compensate for each other in breast tumor cell lines vs. HMECs was related to the level of CDK inhibition achieved. We reasoned that in the presence of sufficient p16 (or when CDK4/6 activity is maximally inhibited), as is likely in the breast cancer cells expressing exogenously introduced tet-inducible p16 genes, p107 and/or p130 have sufficient residual compensatory activity to block DNA replication and cell proliferation; however, when p16 is limiting (or CDK4/6 activity is only partially inhibited), as is likely in HMECs in which endogenous p16 is slowly induced, p107 and/or p130 are less efficient at blocking DNA replication and proliferation than pRb. To test this possibility, we assessed the relative susceptibilities of MDA-MB-231 cells expressing shR NAs against different RB family proteins to growth inhibition by PD 0332991, a specific small-molecule inhibitor of CDK4/6.18 These assays showed that the cells expressing shRNAs against pRb had slightly higher IC50 values than cells expressing the control vector or shRNAs against p107 or p130, but the differences were not significant (Fig. 3). Thus the different abilities of RB-family proteins to compensate for each other in breast tumor cell lines vs. HMECs are unlikely to be solely due to the levels of CDK4/6 inhibition achieved.

Figure 3.

Cells expressing shRNAs against pRb were slightly less sensitive than cells expressing shRNAs against p107 or p130 to growth inhibition by a specific CDK inhibitor. The bar graph indicates PD 0332991 mean IC50 values (nM) for MDA-MB-231-derived cell lines transduced with shRNAs against indicated RB-family proteins. Standard deviations (n = 3) along with p values (Student t-test) are shown.

Discussion

We have employed retrovirally transduced shRNAs to determine whether stable growth arrest associated with p16-initiated senescence in human breast epithelial cells is mediated through one or more RB family proteins. Despite pRb, p107 and p130 knockdowns of > 90% in one model employing MCF7-tet-p16 and MDA-MB-231-tet-p16 breast cancer cell lines stably expressing shRNAs against each of the individual RB family proteins, p16 induction still resulted in irreversible G1 growth arrest in each case. This finding suggests that there is some redundancy in the ability of the individual RB family proteins to mediate irreversible growth arrest. Cases of functional redundancy within this gene family have been reported in a number of murine and human cell types.19,20 Our finding that expression of HPV E7, which inactivates all three RB family proteins, prevents p16-induced growth arrest in breast cancer cells is consistent with the concept that at least one RB family protein must be present and functional for growth arrest to occur. Additional support comes from our studies of primary HMECs, in which we found that, unlike the case for individual knockdowns, simultaneous downregulation of all three RB family proteins enabled these cells to efficiently overcome p16-mediated senescence. This finding may explain why aberrations in upstream regulators such as p16, cyclin D1 and CDK4, which presumably affect the regulation of all three RB family proteins simultaneously, are more common than aberrations in the individual RB family proteins themselves in breast cancers. From a clinical standpoint, it is encouraging that even aggressive cancer cells such as MDA-MB-231-sh-pRb, lacking both p53 and pRb tumor suppressors, are susceptible to induction of irreversible senescence. This suggests that therapies employing small-molecule inhibitors of CDK4/6 may be effective even in some tumors lacking functional pRb.

Interestingly, the cancer cell lines in which pRb expression was suppressed showed no resistance to p16-initiated growth arrest, while HMECs in which pRb expression was suppressed exhibited a clear proliferative advantage despite increases in the levels of endogenous p16. The difference in the ability of RB family proteins to compensate for one another in the different experimental systems does not appear to be due simply to the level of CDK inhibition achieved, as cancer cells with suppressed pRb displayed susceptibility to short-term growth inhibition by a small-molecule CDK inhibitor similar to that of pRb-competent cells. It is possible that the differing responses to pRb depletion may result from differences in the abundance and availability of distinct E2F factors in malignant vs. non-malignant cells. In particular, the levels of E2F1 mRNA have been found to be reduced in malignant compared with normal breast tissues.21 Altered stoichiometry, along with stress-induced post-translational modifications and changes in localization22,23 may limit the available E2F1, permitting tighter regulation by p130 and p107 in the absence of pRb.

While the exact reason for the distinctive role of pRb in establishing senescence in normal epithelial cells remains to be established, our results suggest why pRb may be preferentially inactivated during breast cancer progression. Whereas suppression of p107 and/or p130 expression does not affect the survival or growth of normal mammary epithelial cells, inactivation of pRb makes these cells partially resistant to p16-induced senescence, enabling them to survive increased levels of stress. An expanded ability to survive and proliferate under stressful conditions (e.g., oncogene induction, DNA damage or critically short telomeres) could allow pRb-negative HMECs to acquire additional genetic and epigenetic changes, leading eventually to malignant transformation.

Materials and Methods

Cells and retroviruses.

MDA-MB-231 and MCF7 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and cultured in DMEM medium (Invitrogen) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Tet System Approved FBS, Clontech). Primary HMECs were obtained from histologically normal reduction mammoplasty tissues (Cooperative Human Tissue Network) and grown in MEGM medium (Lonza). Inducible expression of p16 was accomplished by inserting a p16 cDNA24 in front of the doxycycline-inducible promoter in the pLenti CMV/TO Neo DEST (685-3) vector,25 and introducing this vector into cells expressing high levels of tetracycline-responsive repressor (tet-R) protein. Retroviruses encoding pRb, p107 and p130 shRNAs were generated in the LMP vector (Thermo Scientific) as previously described in reference 12. Retroviruses encoding HPV16 E6 or E7 genes in the LXSN vector were harvested from stable producer cell lines.26

Immunoblotting.

Total protein lysates were collected and processed for immunoblotting by standard methods. Antibodies used included those against p16 (Ab-1; NeoMarkers), p21 (CP74, Millipore), pRb (554136, BD PharMingen), p107 (sc-318, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), p130 (sc-317, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), cyclin E (sc-481, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and actin (C4, Millipore).

Microscopy.

Cells were viewed and photographed using a phase contrast Nikon Eclipse TS100 microscope (Diagnostic Instruments), and images were processed using SPOT 4.1 software (Diagnostic Instruments).

Quantitative RT-PCR.

Total RNAs were prepared using RNA-EZ kits (Qiagen), and cDNAs were synthesized using iScript cDNA synthesis kits (Bio-Rad). Quantitative RT-PCR reactions were performed using SYBR GreenER kits (Invitrogen) and an iCycler with a MyIQ optical unit (Bio-Rad). The following primers were used:

TBP-CAC GAA CCA CGG CAC TGA TT (F), TTT TCT TGC TGC CAG TCT GGA C (R);

pRb-AAC TCT CAC CTC CCA TGT TGC TCA (F), TTG CTA TCC GTG CAC TCC TGT TCT (R); p107-AAA GGA GAA TGC CTC CTG GAC CTT (F), TTA GCC TGT GCT GTC AGT TTC CCT (R); p130-AAC GCT GGT TCA GGA ACA GAG ACT (F), AGA AAC TGG AGT CAC ACA AGG GCT(R); p16-AGC ATG GAG CCT TCG GCT GAC T (F), ATC ATC ATG ACC TGG ATC GGC CT (R).

Cell cycle analyses.

Cells were dissociated with trypsin, washed with cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS) then resuspended in 0.5 ml ice cold PBS and fixed by drop-wise addition of 4.5 ml of cold 70% ethanol. The cells were then washed with PBS, resuspended in staining solution [PBS, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.2 mg/ml DNase-free RNase A (R-6513, Sigma), 0.02 mg/ml propidium iodide (P-4170, Sigma)], incubated for 30 min at room temperature, then kept at 4°C until assayed. Flow cytometry was performed using a FACSCalibur instrument (Becton Dickinson), and results were analyzed using FlowJo 9.3.3 software.

Proliferation assays.

Growth inhibition by PD0332991 was determined as described in reference 27. Briefly, cells were seeded in triplicate at 5,000 cells per well in 24-well plates. After 24 h, they were treated with seven concentrations of PD 0332991 (1,000, 500, 250, 125, 62.5, 31.25 and 0 nM) in growth medium. After a 6-d incubation, the cells were harvested and counted, and dose-response curves were generated. Three independent experiments were performed, and IC50 values were compared using Student t-test (www.physics.csbsju.edu/stats/t-test_bulk_form.html).

Acknowledgements

We thank Pfizer Inc., for providing the specific CDK4 inhibitor, PD-332991. This work was supported by Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute Young Clinical Investigator Award 032122 (A.V.B.), Komen for the Cure Research Grant BCTR0707231 (A.V.B.), Breast Cancer and the Environment Research Project U01 ES019458 (P.Y.), and the Office of Energy Research, Office of Health and Biological Research, US Department of Energy under Contract No. DEAC02-05CH11231 (P.Y.).

Abbreviations

- CDK

cyclin-dependent kinase

- p16

CDKN2A gene product

- HMEC

human mammary epithelial cell

- p21

CDKN1A gene product

- p107

RBL1 gene product

- p130

RBL2 gene product

- pRb

retinoblastoma gene product

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were dislosed.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Campisi J, d'Adda di Fagagna F. Cellular senescence: when bad things happen to good cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:729–740. doi: 10.1038/nrm2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Courtois-Cox S, Jones SL, Cichowski K. Many roads lead to oncogene-induced senescence. Oncogene. 2008;27:2801–2809. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Narita M, Lowe SW. Senescence comes of age. Nat Med. 2005;11:920–922. doi: 10.1038/nm0905-920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prieur A, Peeper DS. Cellular senescence in vivo: a barrier to tumorigenesis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hornsby PJ. Senescence and lifespan. Pflugers Arch. 2010;459:291–299. doi: 10.1007/s00424-009-0723-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sage J, Mulligan GJ, Attardi LD, Miller A, Chen S, Williams B, et al. Targeted disruption of the three Rb-related genes leads to loss of G(1) control and immortalization. Genes Dev. 2000;14:3037–3050. doi: 10.1101/gad.843200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Du W, Pogoriler J. Retinoblastoma family genes. Oncogene. 2006;25:5190–5200. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malumbres M, Ortega S, Barbacid M. Genetic analysis of mammalian cyclin-dependent kinases and their inhibitors. Biol Chem. 2000;381:827–838. doi: 10.1515/BC.2000.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cobrinik D. Pocket proteins and cell cycle control. Oncogene. 2005;24:2796–2809. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burkhart DL, Sage J. Cellular mechanisms of tumour suppression by the retinoblastoma gene. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:671–682. doi: 10.1038/nrc2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Treré D, Brighenti E, Donati G, Ceccarelli C, Santini D, Taffurelli M, et al. High prevalence of retinoblastoma protein loss in triple-negative breast cancers and its association with a good prognosis in patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1818–1823. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chicas A, Wang X, Zhang C, McCurrach M, Zhao Z, Mert O, et al. Dissecting the unique role of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor during cellular senescence. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:376–387. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bazarov AV, Van Sluis M, Hines WC, Bassett E, Beliveau A, Campeau E, et al. p16(INK4a)-mediated suppression of telomerase in normal and malignant human breast cells. Aging Cell. 2010;9:736–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00599.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bykov VJ, Issaeva N, Shilov A, Hultcrantz M, Pugacheva E, Chumakov P, et al. Restoration of the tumor suppressor function to mutant p53 by a low-molecular-weight compound. Nat Med. 2002;8:282–288. doi: 10.1038/nm0302-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Narisawa-Saito M, Kiyono T. Basic mechanisms of high-risk human papillomavirus-induced carcinogenesis: roles of E6 and E7 proteins. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:1505–1511. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00546.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yaswen P, Stampfer MR. Molecular changes accompanying senescence and immortalization of cultured human mammary epithelial cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2002;34:1382–1394. doi: 10.1016/S1357-2725(02)00047-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poon RY, Hunter T. Expression of a novel form of p21Cip1/Waf1 in UV-irradiated and transformed cells. Oncogene. 1998;16:1333–1343. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fry DW, Harvey PJ, Keller PR, Elliott WL, Meade M, Trachet E, et al. Specific inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 by PD 0332991 and associated antitumor activity in human tumor xenografts. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:1427–1438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Viatour P, Somervaille TC, Venkatasubrahmanyam S, Kogan S, McLaughlin ME, Weissman IL, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell quiescence is maintained by compound contributions of the retinoblastoma gene family. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:416–428. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson JG, Pereira-Smith OM. Primary and compensatory roles for RB family members at cell cycle gene promoters that are deacetylated and downregulated in doxorubicin-induced senescence of breast cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:2501–2510. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.7.2501-10.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Worku D, Jouhra F, Jiang GW, Patani N, Newbold RF, Mokbel K. Evidence of a tumour suppressive function of E2F1 gene in human breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:2135–2139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin WC, Lin FT, Nevins JR. Selective induction of E2F1 in response to DNA damage, mediated by ATM-dependent phosphorylation. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1833–1844. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stevens C, Smith L, La Thangue NB. Chk2 activates E2F-1 in response to DNA damage. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:401–409. doi: 10.1038/ncb974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beauséjour CM, Krtolica A, Galimi F, Narita M, Lowe SW, Yaswen P, et al. Reversal of human cellular senescence: roles of the p53 and p16 pathways. EMBO J. 2003;22:4212–4222. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Campeau E, Ruhl VE, Rodier F, Smith CL, Rahmberg BL, Fuss JO, et al. A versatile viral system for expression and depletion of proteins in mammalian cells. PLoS One. 2009;4:6529. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garbe J, Wong M, Wigington D, Yaswen P, Stampfer MR. Viral oncogenes accelerate conversion to immortality of cultured conditionally immortal human mammary epithelial cells. Oncogene. 1999;18:2169–2180. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Finn RS, Dering J, Conklin D, Kalous O, Cohen DJ, Desai AJ, et al. PD 0332991, a selective cyclin D kinase 4/6 inhibitor, preferentially inhibits proliferation of luminal estrogen receptor-positive human breast cancer cell lines in vitro. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11:77. doi: 10.1186/bcr2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.