Abstract

Objective

A first study to compare suicides by missing persons with other suicide cases.

Design

Retrospective cohort study for the period 1994–2007.

Geographical location

Queensland, Australia.

Population

194 suicides by missing persons and 7545 other suicides were identified through the Queensland Suicide Register and the National Coroners Information System.

Main outcome measure

χ2 statistics and binary logistic regression were used to identify distinct characteristics of suicides by missing persons.

Results

Compared with other suicide cases, missing persons significantly more often died by motor vehicle exhaust gas toxicity (23.7% vs 16.4%; χ2=7.32, p<0.01), jumping from height (6.7% vs 3.2%; χ2=7.08, p<0.01) or drowning (8.2% vs 1.8%; χ2=39.53, p<0.01), but less frequently by hanging (29.4% vs 39.9%; χ2=8.82, p<0.01). They were most frequently located in natural outdoors locations (58.2% vs 11.1%; χ2=388.25, p<0.01). Persons gone missing were less likely to have lived alone at time of death (OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.76), yet more likely to be institutionalised (OR 3.12, 95% CI 1.28 to 7.64). They were less likely to have been physically ill (OR 0.64, 95% CI 0.43 to 0.95) or have a history of problematic consumptions of alcohol (OR 0.52, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.87). In comparison to other suicide cases, missing persons more often communicated their suicidal intent prior to death (OR 1.58, 95% CI 1.13 to 2.22).

Conclusions

Suicides by missing persons show several distinct characteristics in comparisons to other suicides. The findings have implications for development of suicide prevention strategies focusing on early identification and interventions targeting this group. In particular, it may offer assistance to police in designing risk assessment procedures and subsequent investigations of missing persons.

Article summary

Article focus

Many countries are affected by the phenomenon of missing persons. In Australia, approximately 35 000 people are formally reported as missing every year.

One of the reasons people go missing is to commit suicide.

This study is the first to compare suicides by missing persons with other suicide cases.

Key messages

Suicides by persons gone missing accounted for 2.5% of all suicides in Queensland, Australia.

Compared with other suicides, missing persons were more often found in natural outdoors locations and used methods such as motor vehicle exhaust gas toxicity, jumping from height or drowning. Hanging was proportionately less frequent in suicides by missing persons compared with all other suicides.

Missing persons were more likely to be institutionalised at time of death than other suicide cases, and more often communicated their suicidal intent. In addition, they were less likely to live alone, have a physical illness and/or alcohol problems.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The methodological strength of the study was its cohort design.

The limitations of this study include likely underenumeration of missing persons who died by suicide due to inconsistencies in police recording procedures and identification of such cases through used data sources. Also, accuracy of information obtained from the deceased's next of kin could be impacted by recall bias.

Introduction

In Australia, an estimated 35 000 persons are reported as missing to the police and other search agencies each year, corresponding to a rate of 1.7/1000.1 A definition currently in use in Australia states that a missing person is ‘anyone who is reported missing to police, whose whereabouts are unknown, and where there are fears for the safety or concerns for the welfare of that person’ (James et al, page 4).2 However, the implementation of the definition varies as each police agency has its own criteria and procedures by which it records missing persons. It has also been noted that many missing persons remain unreported, particularly among certain subgroups, such as youth, homeless, indigenous, LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender persons), persons with intellectual disabilities and those from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds.2

The reasons why people go missing are numerous and diverse. Most missing persons leave voluntarily to avoid some adverse physical, social or economic circumstances or following stressful events.3 Biehal et al4 proposed a ‘continuum of missingness’ to describe different groups within the missing persons population, ranging from intentional to unintentional absence with the following categories: ‘decided’ (relationship breakdown, escaping personal problems or violence), ‘drifted’ (losing contact, transient lifestyle), ‘unintentional absence’ (Alzheimer's disease or other mental health problems, accident, misadventure) to ‘forced’ (victim of foul play). Without differentiating between reasons for going missing, mental health concerns are on average recognised in almost half of reports of missing persons and are particularly common among older persons.3 Majority of missing persons is found alive within a short time frame: 35% on the same day and more than three-quarters within the following 2 days.5 The percentage of those found dead either due to foul play or suicide has been estimated to be between 0.3%4 and 1%.6 7 However, at present, it remains difficult to accurately quantify the proportion of missing persons suffering harm while missing, as the outcomes of their disappearances are not routinely recorded by most police forces.2 7

An Australian study that examined differences between persons in three different categories of reasons for going missing (runaway, foul play, suicide) found that missing persons with suicidal intention were more likely to be male, single, aged between 41 and 65 years and without children.8 Other distinct characteristics of this group of missing persons were depression, history of suicide attempt or threats and a wide range of short- and long-term life stressors. Their disappearance was thought to be out of character for great majority of persons who went missing, and in almost 80% of these cases, the reporting person correctly identified suicide as a possible motive for disappearance. While representing a significant contribution to the field, the study was limited by the fact that it merged suicide attempts and completed suicides in one group when in fact these two populations are distinguished by a number of factors.9 To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to explore characteristics of cases of completed suicides reported to police as missing persons prior to death in comparison to all other suicides, in an attempt to determine whether persons who go missing represent a unique subpopulation of persons at-risk for suicide.

Methods

Data sources

Two data sources were used to identify suicide cases reported as missing persons prior to death: Queensland Suicide Register (QSR), an independent databank on suicide mortality, and the National Coroners Information System, an internet database of coronial cases. Only cases where a report was made of persons' disappearance and they were later found to have died by suicide were included (excluding persons who have been found alive after being declared missing and who suicided some time later).

In the QSR, information on possible deaths by suicide is gathered for all Queensland residents from four sources: the police report to the coroner following a possible suicide (which includes a psychological autopsy questionnaire), postmortem report, toxicology results and coroner's findings. Information was obtained predominately from the deceased's next of kin, and occasionally supplemented by records from police or hospital documents. Only cases classified as ‘beyond reasonable doubt’ and ‘probable’ based on the suicide classification used in the QSR were included in the analysis (for more details on the criteria used in determination of level of certainty for death to be concluded as suicide, see examples from past studies10 11).

Analysis

Bivariate analyses (χ2 statistics) were used to compare suicides by missing persons with ‘non-missing’ suicides in socio-demographic, medical and psychiatric variables, past suicidality and life events preceding death, as well as distribution of suicide methods and locations where bodies were found. Variables found to significantly differentiate between the two groups in bivariate models were then entered into binary logistic regression model (using method of forced entry). Statistically significant differences were identified by using level of significance set at p<0.05.

Results

Prevalence

Of the 7739 suicide deaths by Queensland residents between 1994 and 2007, 194 cases were reported to police as missing persons prior to death, accounting for 2.5% of all suicides. Of those, 153 (78.9%) were men and 41 (21.1%) were women. The number of all other suicide cases (‘non-missing’) over the observed time period was 7545.

Suicide methods

As previously observed in Queensland12 and Australia,13 most common suicide method used in both groups was hanging, though used significantly more often by ‘non-missing’ suicides than all other suicides (39.9% vs 29.4%; χ2=8.82, df=1, p<0.01) (figure 1). On the other hand, methods used significantly more frequently in suicides by missing persons were motor vehicle exhaust gas toxicity (23.7% vs 16.4%; χ2=7.32, df=1, p<0.01), drowning (8.2% vs 1.8%; χ2=39.53, df=1, p<0.01) and jumping from high places (6.7% vs 3.2%; χ2=7.08, df=1, p<0.01).

Figure 1.

Suicide methods by missing persons and all other cases. *Difference is significant at level p<0.05.

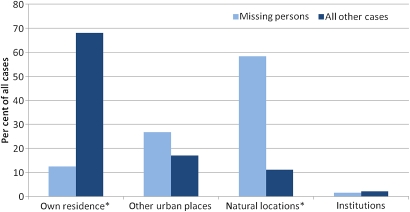

Locations of suicide

In ‘non-missing’ cases, the most common location of suicide was person's own residence (68.0% vs 12.4% of missing persons; χ2=263.74, df=1, p<0.01) (figure 2). Missing person bodies were mostly found in natural locations, such as bushland, roads, on beaches/river banks and under cliffs or mountains (58.2% vs 11.1% of ‘non-missing’ cases, χ2=388.25, df=1, p<0.01). About one-quarter of missing persons cases were found in urban places, such as other person's homes, hotels or parklands, compared with 17.1% of ‘non-missing’ persons (χ2=12.52, df=1, p<0.01).

Figure 2.

Location of suicide by missing persons and all other cases. *Difference is significant at level p<0.05.

Characteristics

Table 1 presents socio-demographic, medical and psychiatric characteristics and recent life events of suicide cases by persons reported as missing prior to death and all other suicides.

Table 1.

Characteristics of suicides by missing persons and all other suicides

| Missing persons, N (%) | All other suicides, N (%) | t | p Value | |

| Mean age (years) | 41.3 | 41.4 | −0.074 | 0.941 |

| Missing persons, N (%) | All other suicides, N (%) | χ2 | df | p Value | |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 153 (78.9) | 5965 (79.1) | 0.004 | 1 | 0.948 |

| Female | 41 (21.1) | 1580 (20.9) | |||

| Marital status* | |||||

| Married | 81 (50.9) | 2464 (39.5) | 8.416 | 1 | 0.004 |

| Not married | 78 (49.1) | 3768 (60.5) | |||

| Ethnicity* | |||||

| Indigenous | 5 (2.7) | 469 (6.7) | 4.656 | 1 | 0.031 |

| Non-indigenous | 180 (97.3) | 6542 (93.3) | |||

| Remoteness area* | |||||

| Metropolitan | 116 (60.1) | 4147 (56.3) | 1.455 | 2 | 0.483 |

| Regional | 69 (35.8) | 2814 (38.2) | |||

| Remote | 8 (4.1) | 409 (5.5) | |||

| Employment status* | |||||

| Employed | 77 (47.5) | 2627 (41.0) | 3.456 | 2 | 0.178 |

| Unemployed | 42 (25.9) | 1691 (26.4) | |||

| Not in labour force | 43 (26.5) | 2091 (32.6) | |||

| Living arrangements* | |||||

| With spouse | 64 (41.6) | 1776 (29.1) | 29.142 | 3 | 0.000 |

| Alone | 21 (13.6) | 1836 (30.1) | |||

| Institution | 8 (5.2) | 121 (2.0) | |||

| Other arrangements | 61 (39.6) | 2365 (38.8) | |||

| Physical and mental health | |||||

| Physical illness (at least one) | 48 (24.7) | 2331 (30.9) | 3.363 | 1 | 0.067 |

| Diagnosed mental illness (at least one) | 95 (49.0) | 2995 (39.7) | 6.782 | 1 | 0.009 |

| Undiagnosed/suspected mental illness | 42 (21.6) | 1274 (16.9) | 3.042 | 1 | 0.081 |

| Contact with mental health professional (last 3 months) | 58 (29.9) | 1772 (23.5) | 4.306 | 1 | 0.038 |

| Drug use | 31 (16.0) | 1729 (22.9) | 5.179 | 1 | 0.023 |

| Problematic alcohol use | 18 (9.3) | 1317 (17.5) | 8.859 | 1 | 0.003 |

| Expressions of suicidality | |||||

| Communicated suicidal intent (lifetime) | 87 (44.8) | 3011 (39.9) | 5.078 | 1 | 0.024 |

| Past suicide attempt (lifetime) | 36 (18.6) | 2109 (28.0) | 2.377 | 1 | 0.123 |

| Suicide note | 85 (43.8) | 2767 (36.7) | 4.145 | 1 | 0.042 |

| Preceding stressful life event | |||||

| Any life event | 111 (57.2) | 4349 (57.6) | 0.014 | 1 | 0.906 |

| Relationship breakdown, separation | 29 (14.9) | 1451 (19.2) | 2.243 | 1 | 0.134 |

| Conflict with partner | 26 (13.4) | 736 (9.8) | 2.834 | 1 | 0.092 |

| Conflict with other persons | 22 (11.3) | 670 (8.9) | 1.406 | 1 | 0.236 |

| Bereavement | 15 (7.7) | 608 (8.1) | 0.236 | 1 | 0.869 |

| Pending legal matters | 12 (6.2) | 561 (7.4) | 0.431 | 1 | 0.512 |

| Financial problems | 15 (7.7) | 585 (7.8) | 0.000 | 1 | 0.991 |

| Recent unemployment | 13 (6.7) | 402 (5.3) | 0.703 | 1 | 0.402 |

| Work/school problems | 9 (4.6) | 395 (5.2) | 0.136 | 1 | 0.712 |

p Values in bold denote statistical difference at level p<0.05.

Cases with unknown or missing value were excluded (marital status: 1348 (17.4%), ethnicity: 543 (7%), remoteness area: 176 (2.3%), employment status: 1168 (15.1%), living arrangements: 1487 (19.2%)).

No significant differences between the two groups were found in their age or gender distribution, but missing persons were significantly more likely to be married (50.9%) and of non-indigenous ethnicity (97.3%) than other suicide cases. At the time of death, missing persons more often lived with a spouse (41.6%) or in an institution (5.2%), had at least one diagnosed mental disorder (49.0%) and had contacts with mental health professionals in last 3 months prior to death (29.9%) (table 1). In comparison to all other suicides, less missing persons had a history of drug use (16.0%) or problematic consumption of alcohol (9.3%).

In terms of history of suicidality, missing persons more often communicated suicide intent during their lifetime (44.8%) and left a suicide note (43.8%). Similar percentages of suicides in both groups experienced at least one significant stressful life event preceding death (about 57%), with most common events recorded in missing persons cases being: relationship breakdown or separation (14.9%), conflict with partner (13.4%) or other significant persons (11.3%), bereavement or financial problems (each in 7.7% of cases), recent unemployment (6.7%) or pending legal matters (6.2%). Nevertheless, no significant differences were found between the two groups in the prevalence of specific stressful life events prior to death.

After adjusting for confounding effects of age and gender, logistic regression analysis identified several characteristics (independent predictors) differentiating between the two groups (table 2). Missing persons were less likely to have lived alone (OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.76), yet more likely to be institutionalised at time of death (OR 3.12, 95% CI 1.28 to 7.64). In addition, they were less likely to have a physical illness (OR 0.64, 95% CI 0.43 to 0.95), have a history of problematic consumption of alcohol (OR 0.52, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.87) or drug use (OR 0.64, 95% CI 0.41 to 1.01). In comparison to all other suicide cases, they more often communicated their intent to suicide (OR 1.58, 95% CI 1.13 to 2.22).

Table 2.

Results of binary logistic regression—independent factors differentiating between suicides by missing persons and all other suicides

| β | SE | OR | 95% CI |

||

| Low | High | ||||

| Institutionalisation | 1.14 | 0.46 | 3.12* | 1.28 | 7.64 |

| Living alone | −0.80 | 0.27 | 0.45** | 0.26 | 0.76 |

| Physical illness | −0.45 | 0.20 | 0.64* | 0.43 | 0.95 |

| Problematic use of alcohol | −0.66 | 0.27 | 0.52** | 0.31 | 0.87 |

| Drug use | −0.45 | 0.23 | 0.64* | 0.41 | 1.01 |

| Communication of suicide intent—lifetime | 0.46 | 0.17 | 1.58** | 1.13 | 2.22 |

Variables entered into regression analysis included age, gender, marital status, ethnicity, suicide note, mental illness, recent contact with mental health professional, physical illness, lifetime communication of suicide intent, alcohol use, drug use, living with spouse, living alone, institutionalisation.

*p<0.05, **p<0.01.

Discussion

The problem of missing persons represents a huge social issue with far-reaching consequences. Even though most people reported missing to Australian police are located within a short period of time (about 85% within a week and 95% within a month),2 the trauma faced by family and friends of persons who go missing is considerable. One study found that for every case of a missing person, an average of at least 12 people suffer adverse effects on their quality of life, with over a third of these persons developing physical and/or mental health problems as a direct consequence.3 This represents an additional health-related burden to the economic costs stemming from searches of missing persons, which were in 1997 estimated to be over $72 million annually.3 However, at the moment, the knowledge of how many people go missing with the intention to complete suicide remains very limited, due to inconsistencies in classification of missing persons, insufficient interagency communication and lack of rigorous research.

Our study aimed to determine whether persons who die by suicide after being reported as missing person show any distinct characteristics in comparisons to other suicides. Significant differences were observed between the two groups in the distribution of suicide methods; bivariate analysis showed that missing persons more often died by motor vehicle exhaust gas toxicity, drowning and jumping, but less frequently by hanging. Furthermore, remains of more than half of missing persons were located in natural, outdoor locations such as bushland, besides roads, on beaches/river banks and under cliffs or mountains. This was in contrast with the majority of other suicides (about two-thirds), which occurred in one's own home. While results of our study do not allow for conclusions on whether the choice of location influenced the selection of suicide method or vice versa, this should be explored in future studies, as it carries significant potentials for improving searches of missing persons based on the detailed assessment of availability and accessibility of specific means of suicide.

In terms of their socio-demographic characteristics, missing persons were more likely to be married and living with their spouse at time of death. After controlling for confounding variables, results confirmed that suicide cases by missing persons less often lived alone than other suicides. Though the data used in our study do not permit any conclusions about the motives for going missing before death, it is possible that a significant proportion of these persons were driven by the desire to spare their significant others the trauma of finding their dead bodies at home. Additional motives might include attempts to prevent their acts from being interrupted and thus increase the likelihood of a completed suicide; avoidance of the stigma attached to suicide for their families and an attempt to have their deaths declared in absentia, which would allows survivors to collect insurance premiums.

Furthermore, suicides by missing persons were found more likely than other suicides to be institutionalised before death. This is in line with findings from the report on missing persons in Australia,3 which showed that 32% of persons had gone missing from an institution, and more than half of those from a psychiatric or mental health institution. Psychiatric inpatients are a well-recognised group of persons at high risk for suicide, with absconding representing an additional factor increasing this risk.14 15 A recent study16 observed distribution of suicide methods among absconders to be different from the patterns recorded in general population, with smaller frequency of hanging and self-poisoning but higher proportion of suicides occurring by jumping and drowning. In addition, absconders were on average found to be young persons, with high rates of schizophrenia, substance misuse and medication non-compliance.17 The need for special attention in allocating resources when looking for absconders has been highlighted in most guidelines for risk assessments, yielding immediate police action.18 19 Though our study did not identify any suicides among youth who have gone missing from other forms of care such as juvenile detention or foster care, data from Australian Capital Territory show that these youngsters account for three-quarters of all young person missing incidents.2 Often experiencing other factors increasing vulnerability (alcohol/drug misuse, adverse social and living circumstances, inadequate coping skills, etc), this is a subpopulation of missing persons that also warrants particular attention.

In terms of physical and mental health, significant differences between the two groups were only found in the prevalence of physical illness, suggesting that those who went missing prior to death were less likely to have some physical illness. At the speculative level, this might indicate that physical health represents a prerequisite for a person to plan and execute their disappearance, and access remote locations where they choose to suicide. On average, missing persons' suicides had a higher prevalence of mental illnesses than all other suicides (recorded in about 50% of cases), yet with no differences in the prevalence of specific disorders. Though this discrepancy was not confirmed as statistically significant in multivariate models (which among other factors accounted for placement in a psychiatric institution at time of death), mental illness undoubtedly represents one of the strongest risk factors for completed suicide20 21 and should as such be one of the most vital components of police protocols used in identifying risk for suicide in missing persons. Compared with ‘non-missing’ cases, missing persons more often expressed their suicidal intent and left a suicide note prior to disappearance. With some studies finding verbal and behavioural clues indicating intent to suicide in up to 90% of suicidal deaths,22 this information should be routinely assessed in all investigations of missing persons and direct immediate search actions. Frequent communication of intent in missing persons suicides might also be seen as an indicator of a (more) thought-out suicide plan,11 23 particularly when that plan includes complex preparations or travelling to distant locations with minimal chances of their suicide acts being interrupted. Greater determination to die and smaller impulsiveness in these subpopulation could be confirmed by the lower prevalence of problematic use of alcohol (including dependence, excessive consumption or frequent binge drinking, associated with violent or non-violent behaviours) or use of illicit drugs. Based on these results, assessment of patterns of use of alcohol and drugs—both known to promote impulsive suicidal behaviours24—could serve as a helpful indicator of individuals' risk for self-harm after their disappearance.

Practical implications of the study

Currently, police uses priority ratings for each case to determine the degree of risk to which people could be exposed after their disappearances or the harm the persons may present to themselves, dividing cases into high, medium and low risk. In general, mental health conditions and signs of suicidality are important factors in determining the category of risk,2 yet the frequency and depth with which they are assessed remains unknown. In Australia, there is currently no standardised form with which information is collected, leaving police officers to rely on their personal judgement in recognising most vulnerable cases and deciding on responses. Clearly, the availability of a statistically sound risk prediction score would be desirable. A handful of studies to date attempted to evaluate the accuracy of predicting certain outcomes of lodgement of missing persons' reports. For example, a survey among friends and relatives of missing persons showed that they expressed safety concerns for the missing person in 19% of cases, yet they turned out be justified only in 1% of cases.3 On the other hand, when looking specifically at suicide cases, a study found that nearly 80% of reporting persons correctly suspected that the missing person had left to die by suicide since indication of intent was present for a large majority of cases.8 Foy8 further attempted to identify reasons for going missing: using a list of 26 variables related to disappearances, she was able to accurately predict 59% of suicide cases, a percentage much lower than in ‘foul play’ or ‘runaway’ cases.

Strengths, limitations and need for future research

A major strength of this study was its cohort design, which allows for comparisons of suicides by persons reported as missing to police at the time of death with other suicide victims. As the majority of information used in this analysis was obtained through an interview by police officers with the deceased's next of kin, their accuracy is likely to be influenced by recall bias resulting from both complex grief following the disappearance and suicide of their loved one, as well as retrospective recollection of events.25 26 In addition, our study was unable to capture all factors that may be relevant to suicidality among missing persons, such as broader consideration of societal and cultural factors related to their disappearances. In the future, this limitation could be partly overcome by conducting psychological autopsy interviews,27 modified in a way to allow for targeted examination of the motivations behind disappearances. A similar study could be performed with persons reported as missing persons but whose suicidal acts were interrupted, as they could offer an even more reliable insight into reasons for going missing before engaging in suicidal behaviours.

An indefinite number of suicides occur annually by persons whose whereabouts are unknown but are never reported as missing persons to police3 or have failed to be identified as such through used data sources. This is partly due to confusion created by various definitions of missing persons and procedures in recording missing person currently used in Australia.19 Achieving uniform classification of missing person and consistency in collections of resolution details28 is therefore of paramount importance and represents a crucial milestone in advancing with research in this area.

Conclusions

Every year, the total number of missing persons might harbour a significant percentage of suicides in Australia. Persons officially recorded as ‘missing’ accounted for approximately 2.5% of all suicides considered in this study; however, it should be noted that there might be a bigger than this number of persons who eventually died by suicide, but their cause of death has not been classified as such (ie, ‘unreported’ cases). Consequently, the global dimension of the phenomenon can only be estimated but not precisely defined.

The present study demonstrated several distinct characteristics of suicides by missing persons compared with all other suicides. Significant differences were evident in terms of suicide methods and locations where the deceased were found, as well as factors related to living circumstances and physical and mental well-being. While this area of research is still in its infancy, it carries significant potential for successful translation of its findings into practice.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

To cite: Sveticic J, Too LS, De Leo D. Suicides by persons reported as missing prior to death: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000607. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000607

Contributors: JS participated in the design of the study, performed the statistical analysis and contributed to the writing of the paper. LST contributed to the data analysis and the writing of the paper. DDL conceived the project, participated in the design of the study and helped to finalise the manuscript for publication. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: Queensland Health provides continuous funding and support in the management of Queensland Suicide Register, which was used as the primary data source for the study.

Competing interest: None.

Ethics approval: The use of data from the Queensland Suicide Register has continuing ethnical approval from the Griffith University Ethics Committee (GU Ref No: CSR/02/10/HREC), and use of data from National Coronial Information System has approval by Department of Justice Human Research Ethics (CF/09/5759).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data from our study are available for sharing.

References

- 1.National Missing Persons Coordination Centre Missing Person: Overview. Canberra: Australian Federal Police, 2008. http://www.missingpersons.gov.au/home/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.James M, Anderson J, Putt J. Missing Persons in Australia. Research and Public Policy Services, No. 86. Canberra: Australian Federal Police, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henderson M, Henderson P. Missing People: Issues for the Australian Community. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biehal N, Mitchell F, Wade J. Lost from View: Missing Persons in the UK. Bristol: The Policy Press, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henderson M, Henderson P, Kiernan C. Missing Persons: Incidence, Issues and Impacts. Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice, No. 144. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newiss G. “Understanding the risk of going missing: estimating the risk of fatal outcomes in cancelled cases”. Policing 2006;29:246–60 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tarling R, Burrows J. The nature and outcome of going missing: the challenge of developing effective risk assessment procedures. Int J Police Sci Mgmt 2004;6:16–26 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foy S. A Profile of Missing Persons in New South Wales. Sydney: Unpublished PhD Thesis in Charles Sturt University, 2006. PhD. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beautrais AL. Suicides and serious suicide attempts: two populations or one? Psychol Med 2001;31:837–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Leo D, Klieve H, Milner A. Suicide in Queensland 2002– 2004: Mortality Rates and Related Data. Brisbane: Australian Institute for Suicide Research and Prevention, Griffith University, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Leo D, Klieve H. Communication of suicide intent by schizophrenic subjects: data from the Queensland Suicide Register. Int J Ment Health Syst 2007;1:6–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Leo D, Evans R, Neulinger K. Hanging, firearm, and non-domestic gas suicides among males: a comparative study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2002;36:183–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Leo D, Dwyer J, Firman D, et al. Trends in hanging and firearm suicide rates in Australia: substitution of method? Suicide Life Threat Behav 2003;33:151–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hunt IM, Kapur N, Webb R, et al. Suicide in current psychiatric in-patients: a case-control study. The National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide. Psychol Med 2007;37:831–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.King EA, Baldwin DS, Sinclair JM, et al. The Wessex recent inpatient suicide study, 2: case-control study of 59 in-patient suicides. Br J Psychiatry 2001;178:537–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hunt IM, Windfuhr K, Swinson N, et al. ; National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness Suicide amongst psychiatric in-patients who abscond from the ward: a national clinical survey. BMC Psychiatry 2010;10:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bowers L, Jarrett M, Clark N, et al. Determinants of absconding by patients on acute psychiatric wards. J Adv Nurs 2000;32:644–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newiss G. Missing Presumed? The Police Response to Missing Persons in Police Research Series. London: Policing and Reducing Crime Unit, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swanton B, Wyles P, Lincoln R, et al. Missing Persons. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology, 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris EC, Barraclough B. Suicide as an outcome for mental disorders: a meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 1997;170:205–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arsenault-Lapierre G, Kim C, Turecki G. Psychiatric diagnoses in 3275 suicides: a meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2004;4:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shneidman ES. Clues to suicide reconsidered. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1994;24:395–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baca-Garcia E, Diaz-Sestre C, Garcia Resa E, et al. Suicide attempts and impulsivity. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2005;255:152–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilcox CH, Conner KR, Caine ED. Association of alcohol and drug use disorders and completed suicide: an empirical review of cohort studies. Drug Alcohol Depend 2004;76:11–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hawton K, Appleby L, Platt S, et al. The psychological autopsy approach to studying suicide: a review of methodological issues. J Affect Disord 1998;50:269–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pouliot L, De Leo D. Psychological autopsy studies: methodological issues. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2006;36:419–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Isometsa ET. Psychological autopsy studies—a review. Eur Psychiatry 2001;16:379–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Leo D, Dudley M, Aebersold CJ, et al. Achieving standardised reporting of suicide in Australia: rationale and program for change. Med J Aust 2010;192:452–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.