Abstract

Objectives

To determine why so few patients with chronic heart failure in England, Wales and Northern Ireland take part in cardiac rehabilitation.

Design

Two-stage, postal questionnaire-based national survey.

Participants and setting

Stage 1: 277 cardiac rehabilitation centres that provided phase 3 cardiac rehabilitation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland registered on the National Audit of Cardiac Rehabilitation register. Stage 2: 35 centres that indicated in stage 1 that they provide a separate cardiac rehabilitation programme for patients with heart failure.

Results

Full data were available for 224/277 (81%) cardiac rehabilitation centres. Only 90/224 (40%) routinely offered phase 3 cardiac rehabilitation to patients with heart failure. Of these 90 centres that offered rehabilitation, 43% did so only when heart failure was secondary to myocardial infarction or revascularisation. Less than half (39%) had a specific rehabilitation programme for heart failure. Of those 134 centres not providing for patients with heart failure, 84% considered a lack of resources and 55% exclusion from commissioning contracts as the reason for not recruiting patients with heart failure. Overall, only 35/224 (16%) centres provided a separate rehabilitation programme for people with heart failure.

Conclusions

Patients with heart failure as a primary diagnosis are excluded from most cardiac rehabilitation programmes in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. A lack of resources and direct exclusion from local commissioning agreements are the main barriers for not offering rehabilitation to patients with heart failure.

Article summary

Article focus

To determine why so few patients with chronic heart failure in England, Wales and Northern Ireland take part in cardiac rehabilitation.

To find out the features of cardiac rehabilitation centres that offer a service to patients with heart failure.

Key messages

Most cardiac rehabilitation centres in England, Wales and Northern Ireland do not routinely offer cardiac rehabilitation to people with chronic heart failure.

Only one in six cardiac rehabilitation centres offers a dedicated cardiac rehabilitation programme for patients with heart failure.

Those with heart failure (New York Heart Association stages 1–2) after myocardial infarction or coronary revascularisation have the best chance of getting on a cardiac rehabilitation programme.

Lack of resources and exclusion from local commissioning agreements are seen as the main reasons for not offering cardiac rehabilitation to people with heart failure.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The first comprehensive national survey of cardiac rehabilitation services for patients with heart failure with a response rate of 84% conducted with the National Audit of Cardiac Rehabilitation.

The conclusions that can be drawn from stage 2 of the survey are limited because of the low response rate.

Introduction

Heart failure is becoming more prevalent worldwide,1 mainly due to ageing of the population and improved survival after acute cardiac events. In the UK, about 900 000 people are living with heart failure but only a small minority participate in cardiac rehabilitation.2 Numerous national and international evidence-based guidelines have been developed to improve diagnosis and treatment for patients with heart failure and have covered aetiology, prevention, diagnosis and therapeutic interventions.3 4 Exercise training has been evaluated intensively with respect to the benefit that it may provide in the treatment of those with heart failure.5 Evidence from meta-analyses shows that cardiac rehabilitation improves quality of life, reduces symptom burden, reduces readmissions to hospital and may improve survival in patients with systolic heart failure.6 7 In the UK, cardiac rehabilitation has been defined as a ‘multidisciplinary intervention for people with heart disease. Its main aims are to help the patient to recover as quickly and completely as possible and then to reduce to a minimum the chance of recurrence of the cardiac illness’.8

Current guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and European Society of Cardiology recommend cardiac rehabilitation as an effective and safe intervention for heart failure.3 4 9 10 These guidelines all recommend that cardiac rehabilitation programmes should not be restricted to exercise alone but should include education, psychological input and drug therapy; in other words, comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation to enhance self-management and help patients achieve better long-term management of their chronic illness.

Despite the clear recommendations in the various guidelines, only a small minority of people affected by heart failure in the UK, and elsewhere, have participated in cardiac rehabilitation.11 12 In the UK between April 2007 and March 2008, only 1% of patients who participated in cardiac rehabilitation were referred because of heart failure,11 and a recent European survey showed that <20% of patients with heart failure are involved in cardiac rehabilitation.12 Two main reasons may explain the suboptimal provision and uptake of this intervention in people with cardiac rehabilitation: previous guidelines13–15 provided no specific details for healthcare planners about how and where these cardiac rehabilitation services would best be delivered, and healthcare staff involved in frontline cardiac rehabilitation services are unsure about the safety and benefits of cardiac rehabilitation in people with heart failure.16 Recent guidelines from Europe and North America give more detailed information on the content and provision of rehabilitation programmes in heart failure.17 18

Most trials of cardiac rehabilitation have excluded patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction (diastolic heart failure), who make up 54% of the population with heart failure, and it is not clear to what extent they are specifically excluded from cardiac rehabilitation in routine practice.19 In the UK, an emphasis has been placed on providing choice between hospital-based rehabilitation and home-based individual programmes such as the Heart Manual20 after myocardial infarction, as such a choice has been shown to increase uptake.21

We conducted a two-stage national survey in 2009–2010. This study aimed first to ascertain why such a small percentage of people with heart failure are receiving cardiac rehabilitation given that it is so widely acknowledged as beneficial and second to find out more about those centres that are providing a service specifically for heart failure. We therefore assessed current provision of cardiac rehabilitation for patients with heart failure in England, Wales and Northern Ireland (stage 1) and obtained data on the features of cardiac rehabilitation centres that did offer cardiac rehabilitation for patients with heart failure (stage 2).

Methods

Stage 1

Stage 1 of the national survey included all centres that provided phase 3 rehabilitation (graduated exercise training supplemented by education on importance of medication, risk factors, diet, stress management and relaxation training8) in England, Wales and Northern Ireland registered on the National Audit of Cardiac Rehabilitation (NACR) register funded by the British Heart Foundation. Each centre was sent a 17-item one-page postal questionnaire that asked respondents to indicate whether they routinely provided a cardiac rehabilitation service for patients with heart failure and to identify and give brief details about barriers to provision of such a service. The stage 1 questionnaire was mailed out by the NACR office in York (see online appendix for the stage 1 questionnaire). To validate the data, responses from stage 1 in terms of the demographic and activity features of the centres were compared with information from the NACR (the methods and measures used by the NACR are described on and available for download from http://www.cardiacrehabilitation.org.uk/nacr).

Stage 2

Stage 2 of the survey was sent from the Royal Cornwall Hospitals Trust and included all centres that confirmed in stage 1 that they provided a separate cardiac rehabilitation service for patients with heart failure. These centres were sent a 44-item five-page questionnaire designed to find out more about the nature (patient demographics and staffing) and content of their cardiac rehabilitation service (see online appendix for the stage 2 questionnaire). In the first instance, the stage 2 questionnaire was sent by email, with a letter explaining why more detailed information was being requested from the centres. To optimise response rates, non-responders were sent personalised letters with stamped addressed envelopes, and these were followed by reminder emails and telephone calls.

Data analysis

We entered participating centres' responses into an Excel spreadsheet. We undertook frequency analyses for stages 1 and 2. We compared the results of the stage 1 questionnaire between centres that did provide separate cardiac rehabilitation programmes for heart failure and those that did not. We made comparisons using the χ2 test for binary data and Mann–Whitney U tests for ordinal data. We analysed data with SPSS software (V.19).

Results

Stage 1

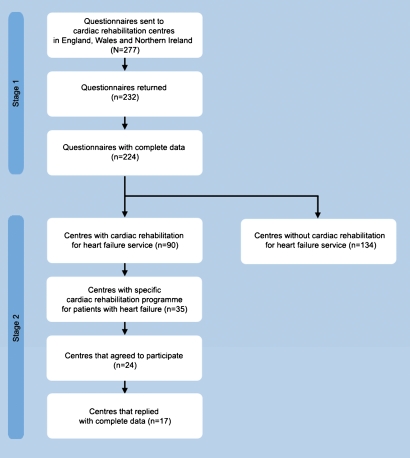

Of the 277 questionnaires sent out to cardiac rehabilitation centres in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, 232 (84%) were completed and returned (figure 1). Eight (3.4%) of these 232 centres did not respond to the first question: ‘Do you routinely offer phase 3 cardiac rehabilitation to people with heart failure?’ which meant that 224 (81%) responses were eligible for full analysis. Table 1 summarises the response to the key questions in stage 1.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart.

Table 1.

Summary of responses to the key questions in stage 1

| Question | Number of responses (%) |

||

| Yes | No | Missing | |

| Do you routinely offer phase III cardiac rehabilitation to people with heart failure? (n=224) | 90 (40.1) | 134 (59.9) | NA |

| Which of these best describes the heart failure pathway into cardiac rehabilitation in your area? | |||

| Usually only if they have been referred for acute myocardial infarction or revascularisation (n=90) | 39 (43.3) | 12 (13.3) | 39 (43.4) |

| We offer cardiac rehabilitation to all people with heart failure regardless of the cause (n=90) | 56 (62.2) | 17 (18.9) | 17 (18.9) |

| We don't usually take people with diastolic heart failure (n=90) | 11 (12.2) | 22 (24.4) | 57 (63.3) |

| Do you provide a separate programme for heart failure patients? (n=90) | 35 (38.9) | 52 (57.8) | 3 (3.3) |

| If yes, are spouses/partners invited to participate in cardiac rehabilitation? (n=90) | 37 (41.1) | 29 (32.2) | 24 (26.7) |

| Do you provide a home-based cardiac rehabilitation programme for heart failure? (n=90) | 27 (30.0) | 56 (62.2) | 7 (7.8) |

| Do you provide a hospital- /centre-based programme for patients with heart failure? (n=90) | 72 (80.0) | 15 (16.7) | 3 (3.3) |

| Do you offer heart failure patients a choice of home- or centre-based cardiac rehabilitation? (n=90) | 30 (33.3) | 56 (62.2) | 4 (4.4) |

| Do you offer cardiac rehabilitation to New York Heart Association class IV patients? (n=90) | 16 (17.8) | 56 (62.2) | 18 (20.0) |

| Do any of the following factors influence you in offering/not offering cardiac rehabilitation to people with heart failure? | |||

| Not enough resources (n=90) | 29 (32.2) | 50 (55.6) | 11 (12.2) |

| HF patients are not included in our contract with the commissioners (n=90) | 16 (17.8) | 54 (60.0) | 20 (22.2) |

| We are not confident that we have the right skill mix/knowledge to manage these patients (n=90) | 8 (8.9) | 67 (74.4) | 15 (16.7) |

| Lack of evidence/guidance on safety (n=90) | 6 (6.7) | 71 (78.9) | 13 (14.4) |

| Lack of evidence on clinical benefit (n=90) | 2 (2.6) | 74 (82.2) | 14 (15.6) |

NA, not applicable.

Of the 224 centres with complete responses, 134 (60%) reported that they did not routinely accept people with heart failure and 90 (40%) that they did routinely offer phase 3 cardiac rehabilitation in heart failure. Of the 90 centres that did offer cardiac rehabilitation in heart failure, 39 (43%) did so only when heart failure was secondary to referral after myocardial infarction or revascularisation. Overall, only 35/224 (16%) responding centres specifically recruited patients with heart failure. Only 33/90 (37%) centres responded to a question asking about their provision of cardiac rehabilitation for patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (diastolic heart failure), with only one-third (11/33) taking patients from this group. Patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction were included in cardiac rehabilitation programmes by 11/90 (12%) centres, with 79 centres accepting only patients with systolic heart failure. Patients with New York Heart Association class IV disease were excluded by 53/90 (59%) centres.

Of the 90 centres that did offer cardiac rehabilitation for heart failure, 35 (39%) had a specific cardiac rehabilitation programme for this patient group. Of these, 27 (30%) offered a home-based cardiac rehabilitation programme such as the Heart Manual or the British Heart Foundation's Heart Failure Plan (see footnote). Hospital-based rehabilitation for groups was offered in 72 (80%) centres, with only 30 (33%) offering a choice between home-based and centre-based programmes (table 1).

From the 134 centres that did not routinely offer rehabilitation in heart failure, 113 (84%) indicated that a lack of resources was a factor and 73 (54%) indicated that the exclusion of such a service from commissioning contracts had influenced decisions on its provision. More than half (54%) of the centres expressed confidence in the skill mix and knowledge of their staff to provide cardiac rehabilitation in heart failure. Table 2 summarises the perceived barriers given by the 90 cardiac rehabilitation centres that offer cardiac rehabilitation for heart failure. Importantly, overall 146/224 (65%) centres considered that evidence on safety was adequate and 159/224 (71%) did not believe that lack of evidence on clinical benefit was an influencing factor.

Table 2.

Perceived barriers to offering rehabilitation from centres that indicated they routinely offer cardiac rehabilitation in heart failure (n=90)

| Reason cited | Number of centres (%) |

| Lack of resources | 29 (32) |

| No contract for heart failure | 16 (18) |

| Heart failure specialist nurse already meets cardiac rehabilitation need | 14 (16) |

| Lack of referrals from heart failure service clinicians | 11 (12) |

| Patients go to another cardiac rehabilitation programme in area | 9 (10) |

| Not confident in having the correct skill mix | 8 (9) |

Comparison between centres that did and did not provide CR in HF (some data obtained directly from the NACR Database)

A higher percentage of patients diagnosed with heart failure were referred to centres that offered cardiac rehabilitation in heart failure (1301/28 231 (4.6%)) than to those that did not (185/32 246 (0.6%)) (p<0.05). A statistically significant difference was also seen in the median number of patients referred per annum between the centres that routinely offered cardiac rehabilitation in heart failure and those that did not (287 vs 202, respectively, p=0.03). Nearly three of four patients seen were men: 57/78 (73%) in centres offering and 85/115 (74%) in those not offering cardiac rehabilitation in heart failure. Patients who survived myocardial infarction (8448/28 231 (32%)) and coronary artery bypass surgery (5047/28 231 (18%)) formed the largest proportion of patients with heart failure receiving cardiac rehabilitation. The skill mix did not differ significantly between programmes that did (n=90) or did not (n=134) offer cardiac rehabilitation except for the number of nurses. Centres not offering rehabilitation in heart failure had a mean of 2.67 (SD 1.79) whole-time nurses compared with a mean of 2.24 (SD 1.85) in centres offering a dedicated rehabilitation programme in heart failure—a difference that was statistically significant (p=0.039) (table 3).

Table 3.

Staffing mix in centres that did (n=90) and did not (n=134) offer cardiac rehabilitation for heart failure

| Discipline | Number of centres (%) |

p Value | |

| Offering cardiac rehabilitation for heart failure (n=90) | Not offering cardiac rehabilitation for heart failure (n=134) | ||

| Consultant/doctor | 7 (7.8) | 10 (7.5) | 0.186 |

| Nurse | 78 (86.7) | 119 (88.9) | 0.039* |

| Exercise specialist | 39 (43.3) | 49 (36.6) | 0.210 |

| Physiotherapist | 48 (53.3) | 75 (56.0) | 0.071 |

| Physiotherapy assistant | 15 (16.7) | 25 (18.7) | 0.736 |

| Dietician | 46 (51.1) | 70 (52.2) | 0.538 |

| Psychologist | 9 (10) | 13 (9.7) | 0.122 |

| Secretary/administrator | 56 (62.2) | 81 (60.4) | 0.700 |

| Healthcare assistant | 5 (5.6) | 13 (9.7) | 0.587 |

| Occupational therapist | 20 (22.2) | 44 (32.8) | 0.760 |

| Pharmacist | 44 (48.9) | 62 (46.3) | 0.225 |

statistically significant.

Stage 2

Only 35 (16%) of the 224 respondents in stage 1 had indicated that they provided a separate cardiac rehabilitation programme for people with heart failure. Of these 35 centres, 24 (69%) agreed to provide more information about their heart failure service and were willing to participate in stage 2 of the survey. Complete stage 2 questionnaires were received from 17 (71%) of these 24 centres.

The geographical area of responding centres was mainly urban (10/17; 59%) or mixed rural and urban (7/17; 41%). The number of patients with heart failure seen annually varied widely, with 5/17 (29%) centres seeing 10–50 referred patients, 4/17 (24%) centres seeing 51–100 patients and 3/17 (18%) seeing more than 100 patients.

Centres with dedicated cardiac rehabilitation services for heart failure were based mainly in district general hospitals (6/17; 35%) or the community (5/17; 29%) or had clinics in both settings (4/17; 24%). A combination of hospital-based and home-based programmes was offered by 7/17 (41%) of centres, with 8/17 (47%) offering only hospital-based programmes. Seven centres offered both centre-based and home-based cardiac rehabilitation, and nearly half (8/17) offered only a centre-based cardiac rehabilitation programme. The duration of the cardiac rehabilitation programmes offered was <6 weeks for 2/17 (12%) of centres, 6–12 weeks for 10/17 (59%) centres and >12 weeks for 4/17 (24%) centres. A home exercise programme was offered in 10 centres.

Supervised exercise training was a key component of almost all (16/17 (94%)) of the dedicated cardiac rehabilitation for heart failure programmes, with 11/17 (65%) centres including sessions lasting up to 1 h and 5/17 (29%) including sessions of up to 2 h. The content of the exercise training variably included warm-up sessions followed by aerobic exercises and resistance training with varying levels of intensity—generally three levels depending on the patient's exercise capacity assessed using rating of perceived exertion. Most centres reported moderate levels of exercise intensity which varied from 40% to 60% of peak heart rate (equivalent to level 3 to 5 on the Borg scale). The equipment used included exercise bikes, rowing machines, treadmills, arm bikes, cross trainers and step-up equipment. Normal physical activity (ie, walking) was used in 13/17 (76%) of centres to promote fitness. All centres provided education on heart failure, self-management, medication and diet.

Anxiety and depression were assessed by more than 80% (14/17) of centres, with 71% using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale questionnaire. More than half of centres referred patients with high levels of anxiety and depression to their general practitioner or counsellor.

Centres that offered a dedicated rehabilitation programme in heart failure employed three to four whole time equivalent members of staff (7/17), with most employing cardiac rehabilitation nurses, physiotherapists, heart failure specialist nurses and a coordinator. Few centres reported employing a psychologist (2/17) or dietician (3/17) as a member of their cardiac rehabilitation teams.

Discussion

Our survey shows that 60% of the cardiac rehabilitation centres in England, Wales and Northern Ireland did not accept patients with heart failure, although most of those completing the survey accepted that there was good scientific evidence of benefit. This is not a new concern. The Healthcare Commission reported in 2007 that only 5.7% of 6998 patients with heart failure surveyed were referred for cardiac rehabilitation.16 A recent audit from England, Northern Ireland and Wales reported that the cardiac rehabilitation service for heart failure was patchy or non-existent in many areas,11 and the 2010 national audit of cardiac rehabilitation (NACR) report states that 60 477 patients participated in cardiac rehabilitation, although one in four cardiac rehabilitation centres excluded patients with heart failure and only 1% of participants were referred because of heart failure.22 The Healthcare Commission also reviewed progress on the implementation of the national service framework for coronary heart disease and highlighted the need to improve access and provision of cardiac rehabilitation services for people with heart failure.16 23 This implementation gap has also been reiterated by the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement.24 Most cardiac rehabilitation centres are not implementing the latest guidance from NICE.10

Our survey aimed to discover why there is a problem with delivery. Most programme coordinators regarded the major barriers to providing a service for heart failure as local commissioning arrangements, local patient pathways, other people (eg, heart failure specialist nurses) providing a similar service or lack of resources. Only a very small number expressed doubt about safety, their competency or the skill mix. A significant difference was identified in the annual number of patients seen in those centres that did and did not have a dedicated heart failure programme, with larger programmes more likely to have such a programme. However, taken as a whole, no difference was seen in the staff mix of programmes that did or did not specifically recruit patients with heart failure save for the number of nurses who featured prominently and interestingly were represented in higher numbers in centres that did not offer a dedicated rehabilitation programme in heart failure. This suggests that most existing cardiac rehabilitation centres could provide such a service if commissioners were to include heart failure in the contract and only a few would require some further education or expertise. It is also noteworthy that while 60%–62% of cardiac rehabilitation centres have administrative and secretarial support, <8% have direct involvement from a physician. Madden et al25 have suggested that ‘Rehabilitation might be perceived differently if presented as part of a treatment programme prescribed by cardiologists rather than as an optional lifestyle improver suggested by nurses, as is current UK practice’.

In contrast to the findings of the Healthcare Commission, which reported that frontline cardiac rehabilitation services are unsure about the safety and benefits of rehabilitation in heart failure,16 our survey found that a lack of evidence on safety or clinical benefit was not a factor that influenced most centres' ability to offer cardiac rehabilitation.

In this survey, only 11/90 (12%) of centres provided any support for the 54% of the heart failure population with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction.26 The latter presents a similar burden to systolic heart failure in terms of healthcare costs, rehospitalisation rates, mortality, exercise intolerance and quality of life.27–29 Good evidence supports the benefits of cardiac rehabilitation in systolic heart failure in terms of quality of life, exercise capacity, reduced rates of hospital readmission related to heart failure and potential improvements in overall survival.6 7 However, the same cannot be said for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, for which evidence is limited; research is therefore needed to assess definitively the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation interventions.

Patients with less severe forms of systolic heart failure (New York Heart Association class I–III) after a heart attack or coronary revascularisation have the best chance of being offered cardiac rehabilitation. The lack of an alternative to centre-based cardiac rehabilitation, because of a lack of evidence, and the lack of referral by healthcare professionals may explain why uptake of cardiac rehabilitation remains suboptimal in patients with heart failure. Offering ‘real and unconstrained’25 choice of home-based and centre-based rehabilitation may help to improve the uptake of rehabilitation in heart failure, as it has in patients after myocardial infarction.21 30

The main reasons people give for not accepting an invitation to attend centre-based cardiac rehabilitation classes are problems with accessibility and parking at their local hospital, a dislike of groups and work or domestic commitments.31–35 These problems might be overcome by home-based programmes, which have been introduced in an attempt to widen access and participation. Evidence on the effectiveness of home-based models of cardiac rehabilitation in people with heart failure is needed so that policymakers and commissioners can decide what to provide as part of a comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation service for people with heart disease. A trial based in the UK of home exercise compared with care by a specialist heart failure nurse, without other educational elements, in patients with stable heart failure on optimised therapy failed to find a benefit in heart failure-specific quality of life.36 However, adherence to the programme was relatively low, with participants having a large number of comorbid conditions that may have required more specialist exercise input rather than a nurse-led service.

Choice in healthcare is a government priority.37 One recent randomised controlled trial of cardiac rehabilitation in a rural setting used a comprehensive cohort design that allowed participants a choice of centre-based or home-based cardiac rehabilitation.30 38 The Cornwall Heart Attack Rehabilitation Management Study (CHARMS) investigators showed that most recruited patients (55%) wanted to choose their method of cardiac rehabilitation and that outcomes did not differ between the randomised and preference arms.38

In October 2011, NICE published updated guidance on commissioning cardiac rehabilitation services to accompany the recommendations within NICE clinical guideline on chronic heart failure.39 The advice will be linked to the outcomes and indicators specified in the NHS outcomes framework and should help ‘commissioners in designing services to improve outcomes for patients and to help the NHS make better use of its resources’.39

Limitations of the study

The conclusions that can be drawn from stage 2 of the survey are limited because of the low response rate (n=17). Although we obtained detailed information about centres that provided a separate cardiac rehabilitation programme for patients with heart failure, inferences from this part of the study should be treated with caution.

Recommendations from this study

Commissioning groups should follow the recently developed NHS Commission's guide to coronary heart disease and the need for cardiac rehabilitation40 and the recently published NICE guidance on commissioning on cardiac rehabilitation39 for all newly diagnosed patients with chronic heart failure. Part of this guidance recommends offering all patients a choice of venue (home or hospital/centre based) for cardiac rehabilitation, although there is little evidence on the effectiveness of home-based models of cardiac rehabilitation in people with heart failure, including programmes that may be suitable for patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction—robust evidence for these is needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the participating cardiac rehabilitation centres, Jemma Lough for her assistance in editing the manuscript, Tony Mourant for comments on earlier drafts of the manuscript and Christopher Hocking for help with the literature search. The BHF Heart Failure Plan has now been replaced with An Everyday Guide to Living with Heart Failure.

Footnotes

To cite: Dalal HM, Wingham J, Palmer J, et al. Why do so few patients with heart failure participate in cardiac rehabilitation? A cross-sectional survey from England, Wales and Northern Ireland. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000787. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000787

Contributors: RL and RT conceived the original idea of conducting the survey. HMD, RT, RL and JP wrote the paper. The survey questionnaires were designed by the BHF Care and Education Research Group at York and the REACH-HF Study Group and administered by CP via the National Audit of Cardiac Rehabilitation office in York and by JW and HMD in Truro. CP and JP were involved in collating the data and data input. JP and RT analysed the data. HMD and RL are joint guarantors for this study. The REACH-HF investigators include the authors HMD, RL, RT and JW, as well as Patrick Doherty, Kate Jolly, Russell Davis, Sally Singh, Jackie Austin, Robert Williams, Colin Green, Colin Greaves, Robin van Lingen, Lorna Geach and John Packard.

Funding: This study was supported by a Programme Development Grant (RP-DG-0709-10111) from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, NIHR or Department of Health.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The Excel spreadsheets with responses from the stage 1 and stage 2 surveys and the data supplied by the National Audit of Cardiac Rehabilitation for this study will be placed in the Dryad repository and readers can access this via the DOI:10.5061/dryad.n6661sh1. The demographic data from the centres are anonymous and the risk of identification of individual centres is low.

References

- 1.Adams KF. Translating heart failure guidelines into clinical practice: clinical science and the art of medicine. Curr Cardiol Rep 2001;3:130–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bethell HJ, Evans JA, Turner SC, et al. The rise and fall of cardiac rehabilitation in the United Kingdom since 1998. J Public Health (Oxf) 2007;29:57–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al. 2009 focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 guidelines for the diagnosis and management of heart failure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines developed in collaboration with the international Society for heart and Lung Transplantation. Circulation 2009;119:e391–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dickstein K, Cohen-Solal A, Filippatos G, et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008: the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the heart failure Association of the ESC (HFA) and endorsed by the European Society of Intensive care medicine (ESICM). Eur Heart J 2008;29:2388–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.European Heart Failure Training Group Experience from controlled trials of physical training in chronic heart failure. Protocol and patient factors in effectiveness in the improvement in exercise tolerance. Eur Heart J 1998;19:466–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies EJ, Rees K, Moxham T, et al. Exercise based rehabilitation for heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2010;12:706–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piepoli MF, Davos C, Francis DP, et al. Exercise training meta-analysis of trials in patients with chronic heart failure (ExTraMATCH). BMJ 2004;328:189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bethell H, Lewin R, Dalal H. Cardiac rehabilitation in the United Kingdom. Heart 2009;95:271–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.NICE Chronic Heart Failure. National Clinical Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management in Primary and Secondary Care. National Guideline No 5. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.NICE Chronic Heart Failure. Management of Chronic Heart Failure in Adults in Primary and Secondary Care. NICE Clinical Guideline CG108. London: NICE, 2010. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13099/50514/50514.pdf (accessed 2 Sep 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 11.British Heart Foundation Cardiac Care and Education Research Group The National Audit of Cardiac Rehabilitation. Annual Statistical Report 2009. London: BHF, 2009. http://www.cardiacrehabilitation.org.uk/nacr/docs/2009.pdf (accessed 12 Nov 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bjarnason-Wehrens B, McGee H, Zwisler AD, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation in Europe: results from the European cardiac rehabilitation Inventory survey. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2010;17:410–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hunt SA, Baker DW, Chin MH, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the evaluation and management of chronic heart failure in the adult: executive summary a report of the American College of Cardiology/American heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines (Committee to Revise the 1995 guidelines for the Evaluation and management of heart failure): developed in collaboration with the international Society for heart and Lung Transplantation; endorsed by the heart failure Society of America. Circulation 2001;104:2996–3007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Remme WJ, Swedberg K. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2001;22:1527–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anonymous. Guidelines for the diagnosis of heart failure. Task Force on Heart Failure of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 1995;16:741–51 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Healthcare Commission Pushing the boundaries. London: Healthcare Commission, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas RJ, King M, Luik K, et al. AACVPR/ACC/AHA 2007 performance measures on cardiac rehabilitation for referral to and delivery of cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention services. Circulation 2007;116:1611–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piepoli MF, Corrà U, Benzer W, et al. Secondary prevention through cardiac rehabilitation: from knowledge to implementation. A position paper from the cardiac rehabilitation Section of the European Association of cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2010;17:1–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lam CS, Donal E, Kraigher-Krainer E, et al. Epidemiology and clinical course of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail 2011;13:18–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewin B. Effects of self-help post-myocardial-infarction rehabilitation on psychological adjustment and use of health services. Lancet 1992;339:1036–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dalal HM, Evans PH. Achieving national service framework standards for cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention. BMJ 2003;326:481–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.British Heart Foundation Cardiac Care and Education Research Group National audit of cardiac rehabilitation. Annual statistical report 2010. London: BHF, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Department of Health Coronary heart disease: national service framework for coronary heart disease. London: DH, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 24.NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement Delivering quality and value. Focus on: heart failure. Coventry: NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement, 2009. http://www.institute.nhs.uk (accessed 11 Nov 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Madden M, Furze G, Lewin RJ. Complexities of patient choice in cardiac rehabilitation: qualitative findings. J Adv Nurs 2011;67:540–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Owan TE, Redfield MM. Epidemiology of diastolic heart failure. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2005;47:320–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liao L, Anstrom KJ, Gottdiener JS, et al. Long-term costs and resource use in elderly participants with congestive heart failure in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Am Heart J 2007;153:245–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kitzman DW, Little WC, Brubaker PH, et al. Pathophysiological characterization of isolated diastolic heart failure in comparison to systolic heart failure. JAMA 2002;288:2144–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gottdiener JS, McClelland RL, Marshall R, et al. Outcome of congestive heart failure in elderly persons: influence of left ventricular systolic function. The Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Intern Med 2002;137:631–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wingham J, Dalal HM, Sweeney KG, et al. Listening to patients: choice in cardiac rehabilitation. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2006;5:289–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones M, Jolly K, Raftery J, et al. ‘DNA’ may not mean ‘did not participate’: a qualitative study of reasons for non-adherence at home and centre-based cardiac rehabilitation. Fam Pract 2007;24:343–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ades PA, Waldmann ML, McCann WJ, et al. Predictors of cardiac rehabilitation participation in older coronary patients. Arch Intern Med 1992;152:1033–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferguson EE. Cardiac rehabilitation – an effective and comprehensive but underutilized program to reduce cardiovascular risk in patients with CVD. US Cardiovasc Dis 2006;II:14–16 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campbell N, Grimshaw J, Rawles J, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation: the agenda set by post-myocardial infarction patients. Health Educ J 1994;53:409–20 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pell J, Pell A, Morrison C, et al. Retrospective study of influence of deprivation on uptake of cardiac rehabilitation. BMJ 1996;313:267–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jolly K, Taylor RS, Lip GY, et al. A randomized trial of the addition of home-based exercise to specialist heart failure nurse care: the Birmingham Rehabilitation Uptake Maximisation study for patients with Congestive Heart Failure (BRUM-CHF) study. Eur J Heart Fail 2009;11:205–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lewis RQ. A new direction for NHS community services. BMJ 2006;332:315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dalal HM, Evans PH, Campbell JL, et al. Home-based versus hospital-based rehabilitation after myocardial infarction: a randomized trial with preference arms—Cornwall Heart Attack Rehabilitation Management Study (CHARMS). Int J Cardiol 2007;119:202–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Advice from NICE Aims To Improve Commissioning of Services for People with Chronic Heart Failure and For People Who Need Cardiac Rehabilitation. London: NICE, 2011. http://www.nice.org.uk/newsroom/pressreleases/chronicheartfailurecardiacrehabilitationcommissioningguides.jsp (accessed 23 Nov 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Department of Health Commissioning a Cardiac Rehabilitation Service: Reabling People with Coronary Heart Disease. London: DH, 2010. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/Browsable/DH_117504 (accessed 23 Nov 2011). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.