Abstract

Introduction

Cost-effectiveness is an important criterion in the decision to cover interventions in health insurance packages. One of the outcome measures, the quality-adjusted life year, has been criticised on its assumptions and implications concerning life expectancy and quality of life. Several studies have been conducted that measured societal preferences concerning healthcare rationing decisions. These studies mainly focused on one attribute. To adjust quality-adjusted life year maximisation in accordance with societal preferences, the relative importance of attributes should be studied. The present study aims to measure the relative importance of age, gender, socioeconomic status, pre-intervention health state, treatment effect, chance of treatment success and number of people in need of the intervention. A secondary objective is to compare the validity of the willingness to pay method with the validity of a relatively new preference elicitation method, best–worst scaling.

Methods and analysis

A representative sample of 2000 Dutch citizens, over 18 years of age, are recruited to complete a web-based survey containing treatment scenarios. The scenarios present different levels of attributes. Respondents are asked to select one of the four scenarios that they prefer to be covered by the Dutch standard health insurance package and one that they prefer not to be covered. They are also asked to indicate how much they are willing to pay for each treatment scenario. At the end of the survey, respondents are asked to rate every attribute on a 1–10 scale. Two versions of the questionnaire are developed which differ on the framing, that is, treatments can be added to or removed from the insurance package. The data will be analysed by means of sequential conditional logit analysis (best–worst scaling) and analysis of variance (willingness to pay).

Ethics and dissemination

The protocol is reviewed and approved by the medical ethical committee of the University Medical Center Leiden.

Article summary

Article focus

How do people value different attributes relative to other attributes in the context of healthcare resource allocation decisions?

How does the validity of the best–worst scaling method compare with the willingness pay method?

Introduction

In the Netherlands, standard health insurance is compulsory for every citizen. The Minister of Health decides which interventions are to be covered by obtaining advice from the Health Care Insurance Board (CVZ). Their advice is based on four criteria: necessity, effectiveness, feasibility and cost-effectiveness.1

The cost-effectiveness of interventions is determined by relating the difference in cost between the intervention and usual care to the difference in effects in terms of quality-adjusted life years (QALYs). QALYs represent the equivalent number of years a person will live in perfect health as a result of an intervention.2 Interventions that gain the most QALYs relative to their cost are prioritised over others (QALY maximisation). The underlying value of this prioritisation rule is that a QALY gained has the same value no matter who gains it (distributive neutrality).3 However, implicit weightings occur when comparing interventions treating specific patient groups.4 For example, interventions for children are likely to gain more QALYs compared with interventions for older people. This is because patients with longer life expectancy will have a longer benefit after treatment. Another factor influencing life expectancy is gender, that is, men have a lower life expectancy compared with women. These differences can be substantial. For example, in the European Union, women live up to 11.7 years longer than men.5 Also, between socioeconomic classes, differences in life expectancy exist. People in the lower socioeconomic classes have a lower life expectancy compared with those in the higher socioeconomic classes.6 In the Netherlands, newborn boys in the lowest socioeconomic class live on average 7.2 years shorter compared with their counterparts in the highest socioeconomic class.7 Because of these differences in life expectancy, similarly effective treatments can be less cost-effective in populations with lower life expectancy. QALYs also favour pre-intervention health states representing high quality of life over health states representing lower quality of life.8 Harris described an example of such a situation in which twin sisters get involved in a car accident. Before the accident, one was living in perfect health, while the other was not. After the accident, a treatment could save their lives and recover both to their pre-accident health state. In this case, the one who lived in perfect health before the accident would gain more QALYs and therefore would be prioritised for treatment. This implies that in case of life-saving treatment, treated morbidity is prioritised over treated co-morbidity.

Finally, the use of QALYs is criticised for the fact that society has been involved in valuing health states but not in other factors incorporated in QALY calculations like the chance of treatment success, the number of people in need of the intervention or life expectancy after treatment.9 10 If, as a result, resource allocation fails to recognise societal preferences, there is a danger that an increasing number of people are no longer willing to pay for standard health insurance.

Consequently, empirical knowledge about factors influencing societal preferences and the relative importance of these factors is necessary. Numerous studies have been conducted to measure how society prioritises healthcare resources. Most of these studies measured preferences on one attribute at a time and, as such, their relative importance is unknown.11 Therefore, a study will be conducted with the aim to measure the relative importance society puts on different attributes when they are presented simultaneously. Furthermore, previous studies measured societal preferences in a variety of ways, for example, by means of discrete choice experiments, person trade-off, time trade-off or willingness to pay (Unpublished data: I. van der Wulp et al.). A relatively new method in studies on healthcare resource allocation preferences is best–worst scaling. Best–worst scaling is an extension of discrete choice experiments in that respondents choose both the best and the worst option from a choice set.12 It is unknown whether the validity of this method is better compared with the validity of other methods. This is important in decisions on what preference elicitation method to apply in a study. Previous studies on the validity of preference elicitation methods were often focused on one method at a time.13 14 As a result, comparing the validity of preference elicitation methods is hampered as most studies also differ on several other aspects. A secondary aim of this study therefore is to compare the validity of the best–worst scaling method with that of the willingness to pay method.

Study questions

How do people value different attributes relative to other attributes in the context of healthcare resource allocation decisions?

How does the validity of the best-worst scaling method compare to the willingness pay method?

Methods and analysis

Study design

Societal preferences are studied in a cross-sectional design.

Study setting and population

A sample of 2000 Dutch citizens over 18 years of age, who are able to speak and read Dutch, are selected by a market research agency. The market research agency has a panel consisting of over 50 000 people. From this panel, a representative sample of respondents is approached by email for participation in the study. This sample will be representative for the Dutch population on age, gender and education status. Respondents are asked to complete a web-based questionnaire containing treatment scenarios. The treatment scenarios present different levels of attributes.

Selection of attributes

The selection of attributes in this study is primarily based on two critics on the use of QALYs, implicit weightings inherent in the QALY and a lack of societal involvement in the valuation of attributes.4 8–10 However, because numerous attributes are associated with the components of a QALY that cause implicit weightings, that is, life expectancy and quality of life, a restriction in the selection of attributes is made. This is to prevent that the task becomes too complex for respondents. The restriction includes only those attributes that have been studied previously because of implicit QALY weightings. As a result, the following attributes related to implicit weightings are selected: age, gender, socioeconomic status, pre-intervention health state and treatment effect. Chance of treatment success and number of people in need of the intervention are selected for their current lack of societal involvement.

Attribute levels

The selection of attribute levels depends, among other things, on the shape of the expected effects, that is, if linear effects are expected, two levels with a wide range can be selected, while if non-linear effects are expected more attribute levels are needed.15

Furthermore, to limit the number of treatment scenarios necessary for an efficient design, it is recommended to use as few attribute levels as possible and as little variation in the number of attribute levels as possible.

Age

In a previous study, Tsuchiya16 reported that younger respondents' preferences concerning age were approximately linear, while those of older people were more convex. A linear effect of the value of age in the present study is therefore not to be expected and more than two attribute levels for age are necessary. Previous studies selected ages representing different phases of the human life span. The same approach is adopted for the present study. The ages 5, 20, 35, 55 and 70 are selected for the present study and derived from Tsuchiya et al.17

Gender

Previous studies including gender as attribute focused on men and women only.18–24 Most studies have not found preferences for one or the other and assume that people prefer interventions for complaints occurring in both sexes. To check this assumption, in the present study, this attribute consists of three levels, interventions for men, women or both sexes.

Socioeconomic status

Several studies have expressed only one of the three aspects of socioeconomic status (income, job position or education status) to their respondents.18–20 22–26 They have reported mixed results. Mooney et al26 and Schwappach27 have expressed all three aspects of socioeconomic status. In the present study, socioeconomic status represents income, job position and education status and is expressed as ‘high’ or ‘low’ status.

Pre-intervention health state and treatment effect

In previous studies, pre-intervention health state has been expressed in a variety of ways, for example, by means of a mobility scale, EQ-5D health states or utilities.28 29 A combination of the latter two is used in the present study by means of presenting utilities combined with the corresponding EQ-5D health state descriptions. Dolan29 used utilities 20, 40, 60, 80 and 100. For the present study, the utilities 20, 40 and 50 are used to express pre-intervention health states. To determine the treatment effect, the attribute post-intervention health state is incorporated in the scenarios in the same way as pre-intervention health state. Post-intervention health states are expressed with utilities 60, 80 and 100. This is to test whether respondents value equal gains equally or whether large gains are valued higher than small gains. In addition, respondents are asked to assume that each post-intervention health state lasts for 1 year. For the ease of interpretation, the utilities are expressed on a Visual Analogue Scale derived from the EQ-5D (table 1).30

Table 1.

Expression of health states

| Health state | Example of Euroqol health state |

| 0–20 |

|

| 21–40 |

|

| 41–60 |

|

| 61–80 |

|

| 81–100 |

|

Chance of treatment success

In previous studies, this attribute was described as prognosis, probability of gain, probability of 5-year survival after treatment or the chance of treatment success.9 31–33 An advantage of the latter description is that it fits chronic as well as acute health states, that is, treatment success does not implicate recovery. It is therefore used in the present study. For the attribute levels, it is considered important to incorporate a probability of 100% as this is a frequently observed outcome in minor health problems and is qualitatively different from the lower levels of success. To cover a full spectrum of prognoses, the other two attribute levels are derived from Ubel and Loewenstein,34 35 that is, 10% and 50%.

Number of people in need of intervention

In previous studies, this attribute has either been expressed as the number of deaths prevented due to the intervention or the number of patients that could be treated.9 26 36–40 The first description can be interpreted as an effect of a preventive intervention, which is not the purpose of this attribute in the present study. Therefore, the second description is used. The prevalence of diseases and complaints in the Netherlands was studied to determine the attribute levels.41 The following attribute levels ranging from relatively rare to relatively common are selected: 3000, 60 000 and 240 000 patients.

Data collection

The data are collected by means of a web-based survey. This survey registers respondents' age, gender, socioeconomic status, health state and whether respondents have additional health insurance for treatments not covered by the standard health insurance package, such as dental care. Health state is measured by means of the EQ-5D.30 Societal preferences are measured by means of treatment scenarios (table 2).

Table 2.

Example of treatment scenario

| Treatment | A |

| Age | 35-year-olds |

| Gender | Men |

| Socioeconomic status | High |

| Number of people in need of intervention | 60 000 |

| Pre-intervention health state | 20 of 100 |

| Post-intervention health state | 80 of 100 |

| Number of patients in which treatment is successful | 10 of 100 |

In the best–worst scaling task, respondents are presented with five sets of four treatment scenarios. This is to prevent respondents for dropping out of the study because of the number of complex tasks that need to be completed. They are asked to select from each set of scenarios the best and the worst scenario depending on the framing of the questionnaire. This is known as case 3 or multi-attribute profile best–worst scaling.42

Two questionnaire versions are developed. Half of the respondents are informed that within the standard health insurance package, there is room for one additional intervention in each set of scenarios. Furthermore, they are informed that each treatment scenario is as costly as another treatment scenario in the same set. Respondents are subsequently asked to select from each set one treatment which they prefer to be covered by the standard health insurance package (best) and one treatment they prefer not be covered (worst). The other half of the respondents are informed that from each set of scenarios, one treatment should be removed from the standard health insurance package because of increasing healthcare costs. They are asked to indicate in each set of scenarios which treatment they prefer to be kept covered by the standard health insurance package (best) and which treatment they prefer to be removed from this insurance package (worst). The first best–worst task is equal for all respondents. In this task, only the number of people in need of the intervention differs between the scenarios, while all other attributes are held constant. This is to test whether respondents understand the task. In a pilot test of the questionnaire, it appeared that 75% of the respondents filled in the expected answer. After each best–worst scaling task, respondents indicate the difficulty of the decision-making task.

In the willingness to pay task, four separate scenarios are presented to respondents. In these tasks, the same types of framing are presented. Half of the respondents are asked by means of an open-ended question how much additional premium they are willing to pay monthly for each of the individual treatments to be covered by the standard health insurance package. The other half are asked to indicate how much additional premium they are willing to pay each month to prevent that the treatment is removed from the standard health insurance package. In both questionnaire versions, they are also asked to indicate their certainty about the amount they are willing to pay and to assume that their monthly health insurance premium is €100 (the approximate average premium for the compulsory health insurance package in the Netherlands).

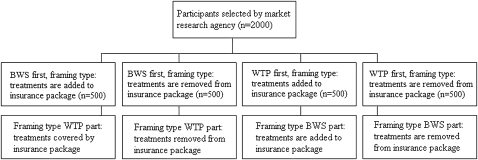

The presented scenarios in the willingness to pay task correspond to one of the sets of the best–worst scaling task. By means of computerised randomisation, respondents receive either the best–worst scaling part or the willingness to pay part of the questionnaire first (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram data collection.

After completing both tasks, they are asked how important (on a 0–10 scale) they consider the attributes under study in the allocation of scarce healthcare resources.

Overall, the questionnaire is framed in an ex ante personally inclusive social perspective, that is, respondents are asked to state their preferences as a member of society while being uncertain about the extent they will use healthcare resources in the future.43

Selection of treatment scenarios

With the before-mentioned selection of attribute levels, a full factorial design consists of 2430 treatment scenarios (2×35×5). The full factorial design is created with the AlgDesign package in R for Windows V.2.10.1 (appendix A).44 The design was initially blocked by means of a nested balanced incomplete block design in 122 blocks with each block consisting of 20 treatment scenarios. Each block was subsequently blocked into five blocks each consisting of four scenarios by means of a balanced incomplete block design. However, in a pilot test of the questionnaire, the resulting best–worst scaling task appeared to be too difficult for respondents as too many attribute levels changed between the four scenarios of each task. All blocks have the same structure, for example, in the first half of the scenarios, socioeconomic status is high, while being low in the second half. Therefore, each of the 122 blocks is allocated into five sets of four scenarios in the order in which they appear in the block. By allocating the scenarios in this way, less variation occurs between the scenarios of a task.

In selecting a balanced incomplete block design, one can set the number of repeated procedures. By repeating the procedure, the AlgDesign package selects n sets of blocked scenarios and compares this selection with the previous selections. From these, the most efficient blocked design is selected.45 By increasing the number of repeated procedures, it is more likely that the most efficient combination of blocks is selected. However, also the computational time increases substantially. When selecting the most efficient model from all possible combinations of 2430 scenarios R should repeat the selection procedure 1.96×1049 times (2430!/(20!(2430–20)!)). As this is too time consuming, the repeated procedures command was set to 50 000. The resulting balanced incomplete block design has substantial diagonality, 0.866, which indicates a relatively small amount of confounding in the design. Also a minimal loss of variance due to blocking is observed (geometric mean of efficiencies: 0.998).

Data analyses

As respondents first choose a scenario that they consider as ‘best’ and subsequently choose a scenario that is considered the ‘worst’ option from a choice set, these data are analysed by means of a sequential conditional logit model. In this analysis, the characteristics of scenarios chosen by respondents as ‘best’ receive a value of 1. The remaining three scenarios not chosen as ‘best’ are valued 0. The scenarios chosen as ‘worst’ receive a value of −1 and the remaining two scenarios not chosen either as ‘best’ or ‘worst’ are valued 0.

In conditional logit modelling, three types of independent variables can be estimated.46

First, generic alternative-specific variables, which are the attributes that vary in the treatment scenarios. In the present study, these variables are age, gender, socioeconomic status, pre-intervention health state, treatment effect, chance of treatment success and the number of people in need of the intervention. Second, alternative-specific variables that vary between the treatment scenarios but have a different impact on the choice alternative, that is, the framing type in the present study. Finally, individual-specific variables which include respondent characteristics, that is, age, gender, socioeconomic status, EQ-5D health state, type of insurance and the degree of difficulty for choosing a ‘best’ and ‘worst’ treatment scenario. The resulting β coefficients from the analysis reflect the impact of a generic alternative-specific variable on the likelihood of choosing another treatment scenario.46 However, these coefficients cannot be used to calculate the relative importance of the attributes as they are biased by underlying utility scale values of each attribute.47 Therefore, the relative importance of each attribute is determined by means of the partial log-likelihood method, that is, by omitting attributes one by one from the model and calculating the overall log likelihood.

The willingness to pay data are analysed by means of analysis of variance. In these analyses, the amount of money people are willing to pay for an intervention is the dependent variable. The independent variables are the attributes, the respondents' characteristics (age, gender, socioeconomic status, EQ-5D health state and type of insurance), the likelihood respondents actually want to pay the chosen amount and the framing type of the questionnaire. In the analyses, the independent variables are tested univariately. Variables significantly (p<0.05) associated with either the best–worst scaling outcome or willingness to pay are selected for multivariate analysis. In multivariate analyses, the main effects will be corrected for seven-way interactions as all attributes are presented to respondents simultaneously.

To determine the validity of the best–worst scaling and willingness to pay method, the resulting relative importance scores of the attributes from both analyses are compared with the rating scores of attributes by means of Pearson correlation coefficients. All analyses are performed in R for Windows V.2.10.1.44

Ethics and dissemination

This paper outlined a study on the relative importance of age, gender, socioeconomic status, pre-intervention health state, treatment effect, chance of treatment success and the number of people in need of the intervention for the societal valuation of health. The protocol has been reviewed and approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the University Medical Center Leiden (P11.022).

The results of this study will be reported in related peer reviewed journals as well as presented on future scientific meetings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Terry Flynn from the University of Technology Sydney for providing helpful suggestions in developing the study.

Footnotes

To cite: van der Wulp I, van den Hout WB, de Vries M, et al. Societal preferences for standard health insurance coverage in the Netherlands: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e0001021. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001021

Contributors: IvdW: developed study protocol and wrote the paper. WBvdH: developed study protocol and critically reviewed early drafts of the paper. MdV: developed study protocol and critically reviewed early drafts of the paper. AMS: developed study protocol and critically reviewed early drafts of the paper. MEvdA: developed study protocol and critically reviewed early drafts of the paper.

Funding: This work was supported by the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw), grant number: 152002019. This publication was financially supported by: The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO).

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was provided by the ethical committee of Leiden University Medical Center.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Zwaap J, Mastenbroek CG, Heiden van der LH. Managing Insurance Coverage In Practice 2 [Pakketbeheer in de Praktijk 2]. Diemen: Coll voor Zorgverzekeringen, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams A. Economics of coronary artery bypass grafting. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1985;291:326–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nord E, Richardson J, Street A, et al. Maximizing health benefits vs egalitarianism: an Australian survey of health issues. Soc Sci Med 1995;41:1429–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harris J. QALYfying the value of life. J Med Ethics 1987;13:117–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Veen van der G. Nederland Langs de Europese Meetlat. Den Haag/Heerlen: Statistics Netherlands, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anand P, Wailoo A. Utilities versus rights to publicly provided goods: arguments and evidence from health care rationing. Economica 2000;67:543–77 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Healthy Life Expectancy; Income, Mean Over 2004/2007 [Gezonde levensverwachting; inkomen, gemiddelde over 2004/2007] Den Haag/Heerlen: Statistics Netherlands, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris J. Unprincipled QALYs: a response to Cubbon. J Med Ethics 1991;17:185–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts T, Bryan S, Heginbotham C, et al. Public involvement in health care priority setting: an economic perspective. Health Expect 1999;2:235–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwappach DL. Resource allocation, social values and the QALY: a review of the debate and empirical evidence. Health Expect 2002;5:210–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dolan P, Shaw R, Tsuchiya A, et al. QALY maximisation and people's preferences: a methodological review of the literature. Health Econ 2005;14:197–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finn A, Lourviere JJ. Determining the appropriate response to evidence of public concern: the case of blood safety. J Public Policy Marketing 1992;11:12–25 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clarke PM. Testing the convergent validity of the contingent valuation and travel cost methods in valuing the benefits of health care. Health Econ 2002;11:117–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Brien B, Viramontes JL. Willingness to pay: a valid and reliable measure of health state preference? Med Decis Making 1994;14:289–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rose MJ, Bliemer MC. Constructing efficient stated choice experiments. Transport Rev 2009;5:587–617 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsuchiya A. The Value of Health at Different Ages. York: University of York, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsuchiya A, Dolan P, Shaw R. Measuring people's preferences regarding ageism in health: some methodological issues and some fresh evidence. Soc Sci Med 2003;57:687–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charny MC, Lewis PA, Farrow SC. Choosing who shall not be treated in the NHS. Soc Sci Med 1989;28:1331–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dolan P, Cookson R, Ferguson B. Effect of discussion and deliberation on the public's views of priority setting in health care: focus group study. BMJ 1999;318:916–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dolan P, Tsuchiya A. Determining the parameters of a social welfare function using stated preference data: an application to health. Sheffield: University of Sheffield, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fortes PA, Zoboli EL. A study on the ethics of microallocation of scarce resources in health care. J Med Ethics 2002;28:266–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Furnham A. Factors relating to the allocation of medical resources. J Soc Behav Pers 1996;11:615–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Furnham A, Meader N, McClelland A. Factors affecting nonmedical participants' allocation of scarce medical resources. J Soc Behav Pers 1998;13:735–46 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Furnham A, Simmons K, McClelland A. Decisions concerning the allocation of scarce medical resources. J Soc Behav Pers 2000;15:185–200 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindholm L, Rosen M, Emmelin M. An epidemiological approach towards measuring the trade-off between equity and efficiency in health policy. Health Policy 1996;35:205–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mooney G, Jan S, Wiseman V. Examining preferences for allocating health care gains. Health Care Anal 1995;3:261–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwappach DL. Does it matter who you are or what you gain? An experimental study of preferences for resource allocation. Health Econ 2003;12:255–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dolan P, Green C. Using the person trade-off approach to examine differences between individual and social values. Health Econ 1998;7:307–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dolan P. The measurement of individual utility and social welfare. J Health Econ 1998;17:39–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The EuroQol Group EuroQol a new facility for the measurement of health related quality of life. Health Policy 1990;16:199–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Browning CJ, Thomas SA. Community values and preferences in transplantation organ allocation decisions. Soc Sci Med 2001;52:853–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gyrd-Hansen D, Kristiansen IS. Preferences for ‘life-saving’ programmes: small for all or gambling for the prize? Health Econ 2008;17:709–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ubel PA, Baron J, Asch DA. Social responsibility, personal responsibility, and prognosis in public judgments about transplant allocation. Bioethics 1999;13:57–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ubel PA, Loewenstein G. Distributing scarce livers: the moral reasoning of the general public. Soc Sci Med 1996;42:1049–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ubel PA, Loewenstein G. Public perceptions of the importance of prognosis in allocating transplantable livers to children. Med Decis Making 1996;16:234–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bleichrodt H, Doctor J, Stolk E. A nonparametric elicitation of the equity-efficiency trade-off in cost-utility analysis. J Health Econ 2005;24:655–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johannesson M, Johansson PO. To be or not to be, that is the question: an empirical study of the WTP for an increased life expectancy at advanced age. J Risk Uncertainty 1996;13:163–74 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ubel PA, DeKay ML, Baron J, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis in a setting of budget constraints–is it equitable? N Engl J Med 1996;334:1174–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ubel PA, Baron J, Nash B, et al. Are preferences for equity over efficiency in health care allocation “all or nothing”? Med Care 2000;38:366–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van Houtven GL. Altruistic preferences for life-saving public programs: do baseline risks matter? Risk Anal 1997;17:85–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Which Diseases Have The Highest Prevalence? [Welke ziekten hebben de hoogste prevalentie?] Bilthoven: National Institute for public health and the Environment, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Flynn T. Valuing citizen and patient preferences in health: recent developments in three types of best-worst scaling. Expert Rev 2010;10:259–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dolan P, Olsen JA, Menzel P, et al. An inquiry into the different perspectives that can be used when eliciting preferences in health. Health Econ 2003;12:545–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing [Computer Program]. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wheeler RE. Comments on algorithmic design. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2009. 23-3-2011. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Croissant Y. Estimation of multinomial logit models in the R mlogit packages. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lancsar E, Louviere J, Flynn T. Several methods to investigate relative attribute impact in stated preference experiments. Soc Sci Med 2007;64:1738–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.