Abstract

Objective

In ST elevation myocardial infarction women received less evidence-based medicine and had worse outcome during the fibrinolytic era. With the shift to primary percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI) as preferred reperfusion strategy, the authors aimed to investigate whether these gender differences has diminished.

Design, setting and participants

Cohort study including consecutive ST elevation myocardial infarction patients registered 1998–2000 (n=15 697) and 2004–2006 (n=14 380) in the Register of Information and Knowledge about Swedish Heart Intensive care Admissions.

Outcome measures

1. Use of evidence-based medicine such as reperfusion therapy (pPCI or fibrinolysis) and evidence-based drugs at discharge. 2. Inhospital and 1-year mortality.

Results

Of those who got reperfusion therapy, pPCI was the choice in 9% in the early period compared with 68% in the late period. In the early period, reperfusion therapy was given to 63% of women versus 71% of men, p<0.001. Corresponding figures in the late period were 64% vs 75%, p<0.001. After multivariable adjustments, the ORs (women vs men) were 0.86 (95% CI 0.78 to 0.94) in the early and 0.80 (95% CI 0.73 to 0.89) in the late period. As regards evidence-based secondary preventive drugs at discharge in hospital survivors (platelet inhibitors, statins, ACE inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers and β-blockers), there were small gender differences in the early period. In the late period, women had 14%–25% less chance of receiving these drugs, OR 0.75 (95% CI 0.68 to 0.81) through 0.86 (95% CI 0.73 to 1.00). In both periods, multivariable-adjusted inhospital mortality was higher in women, OR 1.18 (95% CI 1.02 to 1.36) and 1.21 (1.00 to 1.46). One-year mortality was gender equal, HR 0.95 (95% CI 0.87 to 1.05) and 0.96 (0.86 to 1.08), after adding evidence-based medicine to the multivariable adjustments.

Conclusion

In spite of an intense gender debate, focus on guideline adherence and the change in reperfusion strategy, the last decade gender differences in use of reperfusion therapy and evidence-based therapy at discharge did not decline during the study period, rather the opposite. Moreover, higher mortality in women persisted.

Article summary

Article focus

With (1) the focus on treatment guidelines, (2) the attention on gender differences in management and outcome and (3) the change in reperfusion strategy in STEMI in the last decade, we hypothesised

that gender differences in adherence to treatment guidelines would have diminished and

that gender differences in outcome would have decreased.

Key messages

Management improved and mortality decreased in STEMI patients in the late compared with the early period.

The gender treatment gap did not decrease between the two time periods.

The gender outcome gap did not decrease between the two time periods.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The study included a huge amount of STEMI patients, with enough numbers to assure adequate statistical analyses. Swedish Web-system for Enhancement and Development of Evidence-based care in Heart disease Evaluated According to Recommended Therapies register is a unique Swedish National Quality register, with quality control and audit measures, covering all hospitals in Sweden treating STEMI patients and has standardised criteria for defining MI. Mortality data are complete as the vital status of all Swedish citizens is registered in the Cause of Death Register. One limitation is the non-randomised observational nature. Thus, multivariate analyses were used in order to reduce the bias inherent in this type of studies. Adjustments might be influenced by the lack of registration on some possible confounding factors in the database, for example, non-cardiac comorbidities and contraindications for specific treatments.

Introduction

Numerous studies have shown excess mortality in women after myocardial infarction (MI),1 2 but ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) has seldom been separated from non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes.1 3 Women have been treated less intensively than men4 5 with less reperfusion therapy in the STEMI group.5 Whereas some have found small gender differences in treatment not affecting mortality after MI,3 others have attributed part of the gender gap in outcome to a treatment bias.1 Higher risk of death and bleeding in women is shown in many fibrinolytic trials.2 6 In the last decade, there has been a shift in reperfusion strategy in Sweden from fibrinolytic to primary percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI). Simultaneously, there has been an increase in use of evidence-based cardiovascular secondary preventive drugs, such as statins, P2Y12 inhibitors and ACE inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), and the case fatality has declined. There is less firm evidence that female gender is an independent risk factor for adverse outcome after pPCI which seems to be a better reperfusion strategy for women in particular.7–10 Since 2002/2003, there are separate ESC guidelines for STEMI and NSTE ACS recommending pPCI as the preferred reperfusion strategy in STEMI.11 12 With the last decade's awareness and debate about ACS from a gender perspective, the focus on adherence to treatment guidelines and the shift to a reperfusion strategy, we hypothesised that the previously noticed gender differences in STEMI management would have decreased and thus also the gender gap in mortality, especially in the early phase.

Our aim was to evaluate gender differences in management and outcome in STEMI patients in two time periods with different dominating reperfusion strategies, that is, fibrinolytics and pPCI, respectively.

Methods

Patients

Data for this study came from the prospective observational Register of Information and Knowledge about Swedish Heart Intensive care Admissions (RIKS-HIA), since 2009 merged with the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry, the Swedish Heart Surgery Registry and the National Registry of Secondary Prevention (SEPHIA) together forming the Swedish Web-system for Enhancement and Development of Evidence-based care in Heart disease Evaluated According to Recommended Therapies (SWEDEHEART).13 The RIKS-HIA/SWEDEHEART register is a large national quality register funded by the National Board of Health and Welfare (Socialstyrelsen). It contains information about all patients admitted to coronary care units (CCU) of the participating hospitals in Sweden (95% of the CCUs in Sweden year 2004). Variables including age, sex, smoking habits, comorbidity, delay times, symptoms, biochemical markers, results from cardiac investigations, complications, revascularisation procedures, therapies, discharge diagnoses and outcomes during the hospital stay are continuously recorded on-line over the internet. The criteria for the MI diagnosis were standardised and identical for all participating hospitals.14 15 The register has a continuous internal and external validation of data. The internet-based programme for data input has interactive instructions, manuals, definitions and help functions and a number of compulsory variables and inbuilt validity controls. An independent monitor travels to 20 hospitals annually and in each hospital 30 randomly chosen patients in the database are compared with the hospital records. For example, year 2005, 95.2% and 2006, 96.5% of the registry input showed agreement with the hospital records.

RIKS-HIA/SWEDEHEART is repeatedly further merged with the administrative registers National Cause of Death register and the National Patient Register (National Board of Health and Welfare is responsible for both those registers). The Cause of Death Register covers all Swedish residents, whether the death occurred in Sweden or not and whether the person in question was a Swedish citizen or not. From this register, information was available about cause of death and vital status of all Swedish citizens until 31 December 2007. Regarding comorbidity, data on previous diagnoses of diabetes, hypertension, MI and previous revascularisation procedures were taken from RIKS-HIA, Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry and the Swedish Heart Surgery Registry, which were merged (today SWEDEHEART). Previous history of comorbidities such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), heart failure, chronic kidney disease, peripheral artery disease (PAD), dementia and cancer was obtained from the National Patient Register, including patients hospitalised in Sweden since 1987. Information on previous history of heart failure or stroke was taken both from RIKS-HIA and the National Patient Register. A patient was coded as having the diagnosis if he/she had the diagnosis in either of these registries.

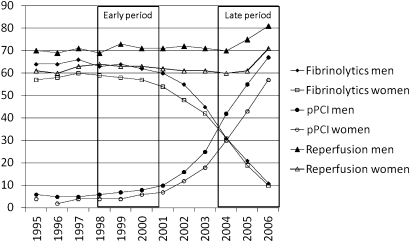

Between 1 January 1995 until 31 December 2006, 54 146 patients were admitted to participating CCUs with the first registry recorded diagnosis of STEMI, defined as ST elevation on admission ECG and a diagnosis of acute MI at discharge. Patients with pacemaker/unknown/unspecified rhythm or bundle branch block on admission were excluded. Two time periods with different dominating reperfusion strategies were chosen (figure 1): patients admitted 1 January 1998 until 31 December 2000 (the early period) and patients admitted 1 January 2004 until 31 December 2006 (the late period). The yearly STEMI prevalence was similar and about 5000 (women comprising 33%–36%) ranging from 4662 (year 2006) to 5308 (year 2000). The groups were compared, and gender comparisons were done in both groups.

Figure 1.

Trends in reperfusion therapy among Swedish STEMI patients from 1995 to 2006. pPCI, primary percutaneous coronary intervention.

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables were summarised by their mean and SD or median and IQR as appropriate. Categorical variables were summarised by counts and percentages. Comparisons between different strata were performed by χ2 tests for categorical variables and by Student t tests or Mann–Whitney tests for continuous variables. p Values <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Crude, age- and multivariable-adjusted ORs with 95% CIs were calculated from logistic regression analyses in order to compare the genders regarding use of cardiac procedures, evidence-based therapies at discharge and inhospital mortality. In addition to sex and age, the multivariable-adjusted analyses included smoking, previous MI, percutaneous coronary intervention, coronary artery bypass grafting, stroke, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, COPD, heart failure, chronic kidney disease, PAD, dementia, cancer within 3 years, therapies on arrival, interventional hospital and year of inclusion. Regarding use of coronary angiography, reperfusion therapy and inhospital mortality, we also added Killip class on arrival and symptom-to-door time (as a continuous variable in 1-h intervals) to the multivariable-adjusted analyses. Data from the logistic regression analyses are shown in forest plots.

HRs with 95% CIs were calculated from Cox proportional hazard regression analyses in order to compare the genders regarding cumulative 1-year mortality. The first multivariable-adjusted analysis included the same variables as first described above. In a second multivariable-adjusted analysis, we also added reperfusion therapy and evidence-based therapies at discharge (platelet inhibitors, β-blockers, ACE inhibitors/ARBs and statins). Data from the Cox regression analyses are shown in forest plots.

Missing values for all variables were controlled (1%–2%). As symptom-to-door time was available for 82% of the patients, a sensitivity analysis was done. Logistic regression analyses regarding use of coronary angiography, reperfusion therapy and inhospital mortality were done also without incorporating symptom-to-door time. These analyses did not substantially change the results (supplementary table).

All statistical analyses were performed with the SPSS (PASW Statistics) V.18.0 software (SPSS, Inc).

Ethical considerations

The register was approved by the National Board of Health and Welfare, and the process of merging the RIKS-HIA register with other registries was approved by the Swedish Data Inspection Board. The study was approved by the ethical committee and complies with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 30 077 STEMI patients were admitted during the two inclusion periods, 15 697 (35% women) in 1998–2000 and 14 380 (35% women) in 2004–2006. The mean age did not differ between the two periods, whereas the prevalence of previous MI was lower, and the prevalence of COPD and smoking was higher in the late period. In both time periods, women were 6.5 years older than men and had more often diabetes, hypertension, heart failure, COPD, or previous stroke, whereas men were more often smokers and were previously revascularised (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics, management and outcome

| Early period: year 1998–2000 |

Late period: year 2004–2006 |

Periods compared | |||||

| Men (n=10151) | Women (n=5546) | p Value | Men (n=9386) | Women (n=4994) | p Value | p Value | |

| Age, in years (SDs) | 66.4 (12.2) | 72.9 (11.5) | <0.001 | 65.9 (12.2) | 72.4 (12.1) | <0.001 | 0.11 |

| Median symptom-to-door time, h:m (IQR) | 2:45 (1:39–5:10) | 3:15 (1:54–6:15) | <0.001 | 3:00 (1:40–5:50) | 3:30 (2:00–6:30) | <0.001 | <0.001† |

| Median time from first ECG to balloon, h:m (IQR) | 1:00 (0:35–1:39) | 0:58 (0:35–1:42) | 0.60 | 1:10 (0:42–1:49) | 1:15 (0:45–1:59) | <0.001 | <0.001† |

| Median time from first ECG to needle, h:m (IQR) | 0:43 (0:27–1:05) | 0:47 (0:30–1:15) | <0.001 | 0:36 (0:20–1:02) | 0:41 (0:23–1:08) | 0.001 | <0.001‡ |

| Comorbidity | |||||||

| Current smoker | 2762 (28.9) | 1220 (23.8) | <0.001 | 2680 (30.9) | 1224 (27.6) | <0.001 | <0.001† |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 1781 (17.5) | 742 (13.4) | <0.001 | 1062 (11.3) | 529 (10.6) | 0.19 | <0.001‡ |

| Previous PCI | 287 (2.9) | 87 (1.6) | <0.001 | 372 (4.0) | 110 (2.2) | <0.001 | <0.001† |

| Previous coronary artery bypass grafting | 307 (3.1) | 58 (1.1) | <0.001 | 308 (3.3) | 82 (1.7) | <0.001 | 0.05† |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1758 (17.3) | 1198 (21.6) | <0.001 | 1679 (17.9) | 1014 (20.3) | <0.001 | 0.82 |

| Hypertension | 2736 (27.2) | 1972 (36.0) | <0.001 | 3053 (32.8) | 2195 (44.5) | <0.001 | <0.001† |

| Congestive heart failure | 586 (5.8) | 518 (9.3) | <0.001 | 406 (4.3) | 455 (9.1) | <0.001 | <0.001‡ |

| Previous stroke | 769 (7.6) | 509 (9.2) | <0.001 | 780 (8.3) | 523 (10.5) | <0.001 | 0.04† |

| Chronic kidney disease | 89 (0.9) | 40 (0.7) | 0.30 | 113 (1.2) | 72 (1.4) | <0.001 | <0.001† |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 448 (4.4) | 358 (6.5) | <0.001 | 465 (5.0) | 440 (8.8) | <0.001 | <0.001† |

| Cancer within 3 years | 246 (2.4) | 160 (2.9) | 0.08 | 277 (3.0) | 149 (3.0) | 0.91 | 0.05† |

| Therapy on arrival | |||||||

| Aspirin | 2680 (26.6) | 1512 (27.5) | 0.25 | 2127 (22.9) | 1440 (29.2) | <0.001 | <0.001‡ |

| Other platelet inhibitor | 37 (0.4) | 16 (0.3) | 0.43 | 309 (3.3) | 195 (3.9) | 0.05 | <0.001† |

| Beta-blocker | 2525 (25.1) | 1544 (28.1) | <0.001 | 2194 (23.6) | 1565 (31.8) | <0.001 | 0.57 |

| ACE inhibitor/ARB | 1081 (10.7) | 586 (10.7) | 0.89 | 1553 (16.7) | 924 (18.7) | 0.002 | <0.001† |

| Statin | 750 (7.5) | 318 (5.8) | <0.001 | 1249 (13.4) | 621 (12.6) | 0.16 | <0.001† |

| Oral anticoagulant | 271 (2.7) | 109 (2.0) | 0.006 | 232 (2.5) | 119 (2.4) | 0.76 | 0.91 |

| Calcium channel blocker | 1304 (13.0) | 786 (14.3) | 0.02 | 1075 (11.6) | 722 (14.6) | <0.001 | 0.04‡ |

| Diuretics | 1453 (14.4) | 1520 (27.7) | <0.001 | 1182 (12.7) | 1407 (28.5) | <0.001 | 0.04‡ |

| Digitalis | 388 (3.9) | 343 (6.3) | <0.001 | 156 (1.7) | 214 (4.3) | <0.001 | <0.001‡ |

| Long-acting nitrates | 1053 (10.5) | 679 (12.4) | <0.001 | 487 (5.2) | 435 (8.8) | <0.001 | <0.001‡ |

| CCU procedures and therapies | |||||||

| Echocardiography | 6200 (64.2) | 2970 (57.8) | <0.001 | 6842 (73.7) | 3282 (66.5) | <0.001 | <0.001† |

| Coronary angiography | 2539 (25.0) | 975 (17.6) | <0.001 | 7686 (81.9) | 3316 (66.4) | <0.001 | <0.001† |

| Reperfusion therapy, all | 7194 (70.9) | 3500 (63.1) | <0.001 | 7065 (75.3) | 3174 (63.6) | <0.001 | <0.001† |

| Fibrinolysis (% of all patients) | 6419 (63.3) | 3223 (58.2) | <0.001 | 1944 (21.0) | 1006 (20.4) | 0.44 | <0.001‡ |

| Fibrinolysis (% of patients receiving reperfusion therapy) | 6419 (89.3) | 3223 (92.2) | <0.001 | 1944 (28.0) | 1006 (32.4) | <0.001 | <0.001‡ |

| Primary PCI (% of all patients) | 713 (7.0) | 248 (4.5) | <0.001 | 4898 (52.2) | 2033 (40.7) | <0.001 | <0.001† |

| Primary PCI (% of patients receiving reperfusion therapy) | 713 (9.9) | 248 (7.1) | <0.001 | 4898 (69.3) | 2033 (64.1) | <0.001 | <0.001† |

| Complications | |||||||

| Killip classes II–IV | 2912 (29.5) | 2077 (38.6) | <0.001 | 991 (11.1) | 847 (18.4) | <0.001 | <0.001‡ |

| Major bleeding* | 67 (1.1) | 62 (2.0) | <0.001 | 104 (1.6) | 120 (4.0) | <0.001 | <0.001† |

| Reinfarction during hospital stay | 281 (2.9) | 205 (3.9) | 0.001 | 150 (1.6) | 94 (1.9) | 0.21 | <0.001‡ |

| Therapy at discharge in hospital survivors | |||||||

| Aspirin | 7994 (87.5) | 4004 (86.1) | 0.02 | 8318 (93.6) | 4062 (91.2) | <0.001 | <0.001† |

| Other platelet inhibitor | 800 (8.8) | 330 (7.1) | 0.001 | 6978 (78.5) | 3045 (68.4) | <0.001 | <0.001† |

| Beta-blocker | 7801 (85.4) | 3812 (82.1) | <0.001 | 8105 (91.2) | 3895 (87.5) | <0.001 | <0.001† |

| ACE inhibitor/ARB | 3934 (43.4) | 1952 (42.4) | 0.25 | 5894 (66.4) | 2719 (61.1) | <0.001 | <0.001† |

| Statin | 3991 (44.0) | 1757 (38.1) | <0.001 | 7570 (85.2) | 3279 (73.8) | <0.001 | <0.001† |

| Outcome | |||||||

| Inhospital mortality | 837 (8.3) | 800 (14.5) | <0.001 | 464 (4.9) | 521 (10.4) | <0.001 | <0.001‡ |

| One-year mortality | 1576 (15.5) | 1324 (23.9) | <0.001 | 961 (10.3) | 955 (19.1) | <0.001 | <0.001‡ |

Data presented as n (%) if not otherwise indicated.

Intracranial haemorrhage, mortal bleeding or given blood transfusion in patients treated with reperfusion therapy.

More in late period.

More in early period.

PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CCU, coronary care unit.

The use of statins, clopidogrel and ACE inhibitors/ARB on admission increased between the two time periods. Women were more frequently treated with diuretics, digitalis, calcium channel blocker and long-acting nitrates on admission in both time periods.

Women had 30 min longer median symptom-to-door time in both time periods. Also the median time from first ECG to needle differed between the genders in both time periods (4 and 5 min, respectively), whereas the median time from first ECG to balloon only differed in the late time period (5 min) (table 1).

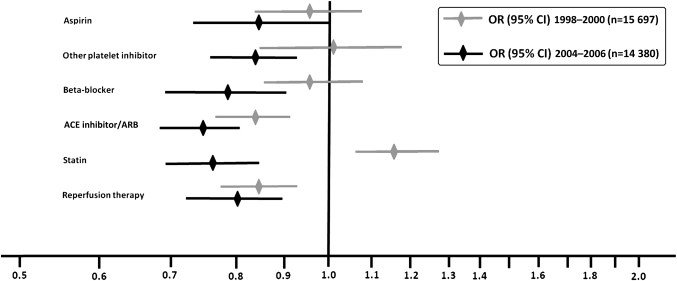

Hospital care

In the early period, coronary angiography was performed in fewer women than men (18% vs 25%). In the late period, the numbers were higher in both genders (66% vs 82%) (table 1). After multivariable adjustments, women had 8% vs 20% less chance of angiography in early and late periods, respectively (OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.02 vs OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.71 to 0.90) (supplementary table). Among patients treated with reperfusion therapy, 9% (7% of women, 10% of men, table 1) were treated with pPCI in the early compared with 68% (64% of women, 69% of men, table 1) in the late period. Sixty-three per cent of women compared with 71% of men received acute reperfusion therapy in the early compared with 64% and 75% in the late period (table 1). After multivariable adjustment, women were 14% and 20% less likely to receive reperfusion therapy in the early and late periods, respectively, compared with men (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.78 to 0.94 vs OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.73 to 0.89) (figure 2, supplementary table). Patients in the early period had more often heart failure and lower Killip class but less major bleedings. In both early and late periods, women had more often heart failure and bleeding complications during hospital stay (table 1).

Figure 2.

Use of coronary angiography, reperfusion therapy and evidence-based therapies at discharge in STEMI patients in two time periods after multivariable adjustments, women versus men.

Therapy at discharge

Evidence-based treatment with statins, platelet inhibitors, β-blockers and ACE inhibitors or ARBs were prescribed more often in the late compared with the early period in both genders. All evidence-based therapies were prescribed more seldom to women in both periods (table 1). Women still had less chance of receiving ACE inhibitors/ARBs but higher chance of receiving statins after multivariable adjustments in the early period. In the late period, women had 14%–25% less chance of receiving any of these therapies after multivariable adjustments, OR 0.75 (95% CI 0.68 to 0.81) through OR 0.86 (95% CI 0.73 to 1.00) (figure 2, supplementary table).

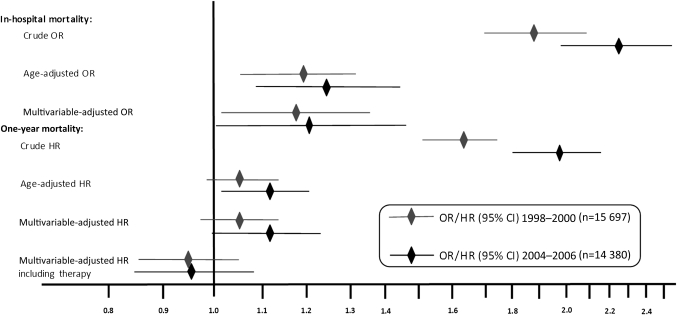

Mortality

Inhospital as well as cumulative 1-year mortality was higher in the early than in the late period in both genders. Women had about twice as high inhospital as well as 1-year mortality in both periods (table 1). After multivariable adjustments, the inhospital mortality was around 20% higher in women in both periods (OR 1.18, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.36 vs OR 1.21, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.46). The 1-year mortality was 5% and 11% higher in women in the early and late periods, respectively, although it did not reach statistical significance in the early period (HR 1.05, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.14 vs HR 1.11, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.24). After adding adjustment for reperfusion therapy and evidence-based treatment at discharge, there was no longer any gender difference in long-term mortality (HR 0.95, 5% CI 0.87 to 1.05 vs HR 0.96, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.08) (figure 3, supplementary table).

Figure 3.

Inhospital and cumulative 1-year mortality in STEMI patients in two time periods with different dominating reperfusion strategies. Crude, age-adjusted and multivariable-adjusted odds and HRs with 95% CIs, women versus men.

Discussion

After the reperfusion strategy change, patients admitted during the first decade of the 21st century were treated with reperfusion therapy more often than patients admitted during the late 1990s. Anyhow, we did not find a diminished gender gap neither regarding use of reperfusion therapy nor regarding mortality. Even more surprising was the finding that women had 14%–25% less chance of receiving evidence-based cardiovascular treatment in the late period after multivariable adjustments.

Previous trials during the fibrinolytic era have found higher mortality in women but usually without separating STEMI from NSTE ACS.1 In STEMI studies, the risk of early death has been 10%–25% higher in women after multivariable adjustments2 5 6 16 although most STEMI cohorts have been extracted from randomised controlled trials2 6 and may not correspond to the real-life population. Fibrinolytics has been given to fewer women even if eligibility has been considered.17 Also in our study, women had 14% lower chance of receiving reperfusion therapy in the early group where fibrinolytics accounted for 91% of the reperfusion therapy. As an increased risk of intracranial haemorrhage and other major bleedings has been found in women treated with fibrinolytics,18 a fear of these dreadful complications may explain some of the observed difference. The well-known longer delay times in women could be another explanation. In our study, women had 30 min longer delay times from symptom onset to arrival to CCU or the cath lab in both time periods. Adjusting for this did not change the results.

As pPCI has been shown superior to fibrinolytics in reducing mortality after STEMI,19 it has been recommended in the ESC guidelines since 2003.20 In Sweden, it has been the dominant reperfusion strategy from 2004 and onwards (figure 1). During this new pPCI era, the evidence that gender per se bears prognostic information is less firm and data are contrasting.10 21 When we started our study and formed our hypothesis, there were only small and mainly single-centre studies published.7 8 10 21 The majority of those did not find female gender to be an independent predictor of adverse outcome after pPCI.7 10 Mehilli et al22 found better myocardial salvage in women than in men after pPCI which they speculated could be due to a higher hypoxia tolerance in women because of higher incidence of preinfarction angina (ischaemic pre-conditioning) and more often spontaneous thrombolysis. Also, as pPCI is less time dependent than fibrinolytics, women could be expected to benefit more than men from a reperfusion strategy change because of their consistently longer symptom-to-door time.10

Thus, our hypothesis was that the gender gap in reperfusion therapy would diminish after the shift to a reperfusion strategy that could be more advantageous to women. This hypothesis was not confirmed. The rate of reperfusion in men increased from 70.9% to 75.3%, whereas the increase in women was very modest, 63.1%–63.6%. The reason for the finding is for us unclear. The gender difference in mean age was the same in the two periods and women had 30 min longer symptom-to-door time in both periods. One possible reason could be higher prevalence of normal coronary arteries in women, which is shown before although mainly in non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes and mixed ACS populations.23 In our study, during the early period, we had coronary angiography findings from few patients (56% of the 3514 patients that underwent coronary angiography). In the late period, we had findings on 97% of the 11 002 examined patients showing that 3% of men and 7% of women had non-obstructive coronary artery disease. Thus, normal coronary arteries can hardly explain the gap in reperfusion therapy in the early period when fibrinolytics was dominating and angiography seldom performed. In the late period, it could account for a small part of the difference in use of pPCI although it does not explain the gender gap in use of coronary angiography, which also increased between the two time periods.

During the last decade, several important randomised controlled trials have been published encouraging more effective secondary prevention in CAD patients.24 25 Use of ACE inhibitors/ARBs, dual platelet inhibition and statins has thus increased dramatically in the STEMI population during this decade and mortality has declined. We found increased use of all secondary prevention drugs, even those with older evidence such as aspirin and β-blockers. However, the increase of all the evidence-based therapies was more pronounced in men than in women. In spite of the intense focus on the gender aspect in the ACS field during the last 2 decades, together with the focus on adherence to guidelines, the treatment gap was even more pronounced in the late compared with the early group. Even after multivariable adjustment, women had 14%–25% lesser chance of receiving any of these drugs at discharge.

We cannot fully explain this gender gap in management. Maybe a fear of doing harm because of the well-known higher risk of bleeding in women26 or reports from patients of previous or current adverse effects are reasons for the bias. It has been shown in previous studies that women report side effects more often than men, especially if the same dosages are used.27 Finally, we could speculate that doctors tend to adapt to new treatment modalities and new guidelines faster in men than in women, especially in older cohorts. We did some subgroup analyses of different age groups (not included in the manuscript) where we found the treatment bias clearest in the oldest cohort.

A more effective reperfusion strategy with pPCI and the increased use of evidence-based treatment have been associated with improved outcome. Thus, we found reduced mortality in the late compared with the early period in both genders. However, we also found a persistent gender gap both regarding short- and long-term mortality. Inhospital mortality was approximately 20% higher in both time periods consistent with previous STEMI studies focusing on gender from the fibrinolytic era.2 5 6 16 From the percutaneous coronary intervention era, two recent publications by Benamer et al and Sadowski et al found that there is still a gender difference in inhospital mortality among STEMI patients consistent with our findings.28 29 In addition, 1-year mortality was higher in our study, 5% vs 11% higher in the early and late periods, respectively. If we also incorporated evidence-based treatment at discharge and reperfusion therapy in the multivariable adjustments, there was no longer a significant gender difference in long-term mortality.

In the USA, the American College of Cardiology's AMI Guidelines Applied in Practice program is proven to increase the use of evidenced-based medicine and reduce MI mortality but is less used in women.30 The results in our study are in concordance with those findings.

Limitations

As in all registries on clinical practice, one limitation is the handling of missing data. In the RIKS-HIA register, we have data for around 95% of the patients for almost all variables that is mandatory for the hospitals to register. Furthermore, as in all observational data sets, the adjustment might be influenced by the lack of registration on some possible confounding factors in the data base, for example non-cardiac comorbidities, reduced kidney function and contraindications for specific treatments. Accordingly, eligibility for all treatments was not possible to ascertain and might thus differ between the genders. However, a strength is the large number of patients allowing adjustment for baseline differences between the compared groups.

Conclusions

Our study showed improved management and reduced mortality in STEMI patients in the late compared with the early period. Anyhow the gender difference did not diminish between the two time periods neither regarding management nor regarding early mortality. Adherence to treatment guidelines was better in men than in women, and in fact, the treatment gap seemed even more pronounced in the new era. There was also a persistent 20% higher risk of early mortality in women in the new pPCI era, in accordance with the fibrinolytic era. Thus, a better adherence to treatment guidelines in women is mandatory as it might reduce the differences in outcome between the genders. There is also a great need of studies scrutinising the gender differences in management of STEMI in the new pPCI era.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all the participating hospitals for their cooperation in contributing data to RIKS-HIA. We would especially like to thank late associate professor Ulf Stenestrand at the Department of Medical and Health Sciences, Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Linköping University Hospital. He, a key founder of the RIKS-HIA register, helped in the preparation of the database and in management, analysis and interpretation of the data.

Footnotes

To cite: Lawesson SS, Alfredsson J, Fredrikson M, et al. Time trends in STEMI—improved treatment and outcome but still a gender gap: a prospective observational cohort study from the SWEDEHEART register. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000726. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000726

Contributors: SSL has substantially contributed to conception and design of the study. She has handled, analysed and interpreted all the data and drafted the article. JA has substantially contributed to conception and design, help with analyses and interpretation of the data. He has revised the draft critically for important intellectual content and approved the final version to be published. MF has substantially contributed with analysing and interpreting the data, revising the draft critically and approved the final version to be published. ES has substantially contributed to conception and design, help with analysing and interpreting the data and revised the draft critically for important intellectual content and approved the final version to be published.

Funding: The RIKS-HIA register (today SWEDEHEART) is supported by the National Board of Health and Welfare, the Swedish Society of Cardiology and the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions. The funding sources had no role in the study such as being involved in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data or in manuscript writing.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: SWEDEHEART/RIKS-HIA is a national quality register funded by the Swedish authorities (National Board of Health and Welfare) where all patients admitted to all coronary care units in Sweden are registered, without need for patient consent forms. Anyhow, the patients are informed about the registration and have the right to deny registration. The researchers do not have access to the unique personal identification codes.

Ethics approval: Uppsala University Hospital Ethical Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There is no additional data available.

References

- 1.Milcent C, Dormont B, Durand-Zaleski I, et al. Gender differences in hospital mortality and use of percutaneous coronary intervention in acute myocardial infarction: microsimulation analysis of the 1999 nationwide French hospitals database. Circulation 2007;115:833–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mega JL, Morrow DA, Ostor E, et al. Outcomes and optimal antithrombotic therapy in women undergoing fibrinolysis for ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Circulation 2007;115:2822–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gan SC, Beaver SK, Houck PM, et al. Treatment of acute myocardial infarction and 30-day mortality among women and men. N Engl J Med 2000;343:8–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bugiardini R, Yan AT, Yan RT, et al. Factors influencing underutilization of evidence-based therapies in women. Eur Heart J 2011;11:1337–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jneid H, Fonarow GC, Cannon CP, et al. Sex differences in medical care and early death after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 2008;118:2803–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berger JS, Elliott L, Gallup D, et al. Sex differences in mortality following acute coronary syndromes. JAMA 2009;302:874–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Luca G, Gibson CM, Gyongyosi M, et al. Gender-related differences in outcome after ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated by primary angioplasty and glycoprotein IIb-IIIa inhibitors: insights from the EGYPT cooperation. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2010;30:342–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antoniucci D, Valenti R, Moschi G, et al. Sex-based differences in clinical and angiographic outcomes after primary angioplasty or stenting for acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2001;87:289–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Luca G, Suryapranata H, Dambrink JH, et al. Sex-related differences in outcome after ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated by primary angioplasty: data from the Zwolle Myocardial Infarction study. Am Heart J 2004;148:852–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Motovska Z, Widimsky P, Aschermann M. The impact of gender on outcomes of patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction transported for percutaneous coronary intervention: analysis of the PRAGUE-1 and 2 studies. Heart 2008;94:e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamm CW, et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: The Tack Force for the management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society for Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2011;32:2999–3054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van de Werf F, Bax J, Betriu A, et al. ; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG) Management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with persistent ST-segment elevation: the Task Force on the Management of ST-Segment Elevation Acute Myocardial Infarction of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2008;29:2909–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jernberg T, Attebring MF, Hambraeus K, et al. The Swedish Web-system for enhancement and development of evidence-based care in heart disease evaluated according to recommended therapies (SWEDEHEART). Heart 2010;96:1617–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tunstall-Pedoe H, Kuulasmaa K, Amouyel P, et al. Myocardial infarction and coronary deaths in the World Health Organization MONICA Project. Registration procedures, event rates, and case-fatality rates in 38 populations from 21 countries in four continents. Circulation 1994;90:583–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alpert JS, Thygesen K, Antman E, et al. Myocardial infarction redefined–a consensus document of The Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the redefinition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;36:959–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Champney KP, Frederick PD, Bueno H, et al. The joint contribution of sex, age and type of myocardial infarction on hospital mortality following acute myocardial infarction. Heart 2009;95:895–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eagle KA, Goodman SG, Avezum A, et al. Practice variation and missed opportunities for reperfusion in ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: findings from the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE). Lancet 2002;359:373–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reynolds HR, Farkouh ME, Lincoff AM, et al. Impact of female sex on death and bleeding after fibrinolytic treatment of myocardial infarction in GUSTO V. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:2054–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keeley EC, Boura JA, Grines CL. Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review of 23 randomised trials. Lancet 2003;361:13–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van de Werf F, Ardissino D, Betriu A, et al. ; Task Force on the Management of Acute Myocardial Infarction of the European Society of Cardiology Management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. The Task Force on the Management of Acute Myocardial Infarction of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2003;24:28–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vakili BA, Kaplan RC, Brown DL. Sex-based differences in early mortality of patients undergoing primary angioplasty for first acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 2001;104:3034–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mehilli J, Ndrepepa G, Kastrati A, et al. Gender and myocardial salvage after reperfusion treatment in acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;45:828–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larsen AI, Galbraith PD, Ghali WA, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients with acute myocardial infarction and angiographically normal coronary arteries. Am J Cardiol 2005;95:261–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, et al. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med 2001;345:494–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yusuf S, Sleight P, Pogue J, et al. Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med 2000;342:145–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manoukian SV. Predictors and impact of bleeding complications in percutaneous coronary intervention, acute coronary syndromes, and ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2009;104(5 Suppl):9C–15C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oertelt-Prigione S, Regitz-Zagrosek V. Gender aspects in cardiovascular pharmacology. J Cardiovasc Transl Res 2009;2:258–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sadowski M, Gasior M, Gierlotka M, et al. Gender-related differences in mortality after ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a large multicentre national registry. EuroIntervention 2011;6:1068–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benamer H, Tafflet M, Bataille S, et al. ; CARDIO-ARHIF Registry Investigators Female gender is an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality after STEMI in the era of primary PCI: insights from the greater Paris area PCI Registry. EuroIntervention 2011;6:1073–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jani SM, Montoye C, Mehta R, et al. ; American College of Cardiology Foundation Guidelines Applied in Practice Steering Committee Sex differences in the application of evidence-based therapies for the treatment of acute myocardial infarction: the American College of Cardiology's Guidelines Applied in Practice projects in Michigan. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1164–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.