Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the prescription of potentially addictive drugs, including analgesics and central nervous system depressants, to women who had experienced intimate partner violence (IPV).

Design

Prospective population-based cohort study.

Setting

Information about IPV from the Oslo Health Study 2000/2001 was linked with prescription data from the Norwegian Prescription Database from 1 January 2004 through 31 December 2009.

Participants

The study included 6081 women aged 30–60 years.

Main outcome measures

Prescription rate ratios (RRs) for potentially addictive drugs derived from negative binomial models, adjusted for age, education, paid employment, marital status, chronic musculoskeletal pain, mental distress and sleep problems.

Results

Altogether 819 (13.5%) of 6081 women reported ever experiencing IPV: 454 (7.5%) comprised physical and/or sexual IPV and 365 (6.0%) psychological IPV alone. Prescription rates for potentially addictive drugs were clearly higher among women who had experienced IPV: crude RRs were 3.57 (95% CI 2.89 to 4.40) for physical/sexual IPV and 2.13 (95% CI 1.69 to 2.69) for psychological IPV alone. After full adjustment RRs were 1.83 (1.50 to 2.22) for physical/sexual IPV, and 1.97 (1.59 to 2.45) for psychological IPV alone. Prescription rates were increased both for potentially addictive analgesics and central nervous system depressants. Furthermore, women who reported IPV were more likely to receive potentially addictive drugs from multiple physicians.

Conclusions

Women who had experienced IPV, including psychological violence alone, more often received prescriptions for potentially addictive drugs. Researchers and clinicians should address the possible adverse health and psychosocial impact of such prescription and focus on developing evidence-based healthcare for women who have experienced IPV.

Article summary

Article focus

Cross-sectional studies have suggested that IPV is associated with increased medication use in women.

Although substance abuse is common among women who have experienced IPV, former studies have not addressed the prescription of drugs with addiction potential.

We assessed the relationship of IPV to prescription rates for potentially addictive drugs, including analgesics and central nervous system depressants, for women in Oslo, Norway.

Key messages

This longitudinal study showed that women who had experienced IPV, including psychological violence alone, more often received prescriptions for potentially addictive drugs compared with other women.

Prescription rates were increased both for potentially addictive analgesics and central nervous system depressants.

Women who had experienced IPV more often received prescriptions from multiple physicians.

Strengths and limitations of this study

A major strength is the prospective and accurate measurement of drug prescriptions from a national register. The study is population-based and adds new information about the prescription of restricted drugs with verified addictive potential to women with experiences of IPV.

Limitations of the study include the low participation rate and the lack of prescription data between the Oslo Health Study in 2000/2001 until the establishment of the Norwegian Prescription Database in 2004. We had no information if IPV was assessed in connection with prescription and cannot evaluate the appropriateness of drug prescription.

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is associated with a broad range of physical and mental health problems in women, including injuries, chronic pain, depression, anxiety, sleep disorders and substance abuse.1–4 Cross-sectional studies further indicate that women who have experienced violence from an intimate partner are more likely to use analgesic and psychotropic drugs.2 5 6 These drugs can be of clinical benefit in treatment of pain, mental distress and insomnia; however, they do also have several adverse effects. Some of them, such as opioid analgesics and benzodiazepines, may within few weeks of use lead to physical and psychological addiction.7 8 The development of drug tolerance will additionally result in decreasing effectiveness and increasing dose requirements over time. Due to potential dependence and abuse, the authorities have implemented control measures to restrict prescriptions for potentially addictive drugs.9 Still, the overall prescription has increased during the past decade.9 10

There is limited research linking IPV and use of prescription drugs. The current knowledge is primarily based on self-reported drug use from cross-sectional studies.2 5 6 11 Although substance abuse is common among women who have experienced IPV,1 12 previous studies have not addressed prescription of drugs with addiction potential. Former research has also mostly been restricted to IPV comprising physical or sexual violence.3 13 However, recent findings indicate that psychological violence by an intimate partner is common and associated with adverse health outcomes irrespective of whether it is accompanied with physical or sexual violence.5 14

We did a longitudinal analysis of register-based prescription data from women in Oslo, Norway. The aim was to assess the prescription rates for potentially addictive drugs, including analgesics and central nervous system (CNS) depressants, to women who reported physical and/or sexual IPV and psychological IPV alone.

Methods

Data sources

Our study sample was a population-based cohort of women who participated in the Oslo Health Study (HUBRO) in 2000/2001. Prescription data were collected from the Norwegian Prescription Database (NorPD) from its establishment in 1 January 2004 through 31 December 2009. Data from HUBRO, Statistics Norway and NorPD were merged by use of a unique identification number, which is allocated to all individuals living in Norway.

Records from NorPD cover all prescriptions dispensed from Norwegian pharmacies to individuals treated in ambulatory care.15 Drugs are classified according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification.16 Data from NorPD include encrypted identifiers for patients and prescribers, ATC code, defined daily dose (DDD), date of dispensing and if applicable reimbursement code. The indication for prescription is not recorded, but the reimbursement code may in some cases indicate the patient's diagnosis. The DDD determined by WHO collaborating centre for drug statistics is the assumed average maintenance dose per day for a drug used for its main indication in adults.16 Person-time at risk was calculated using information on respondents' month/year of death and emigration from Statistics Norway until 1 January 2006 and month/year of death from NorPD in 2006–2009.

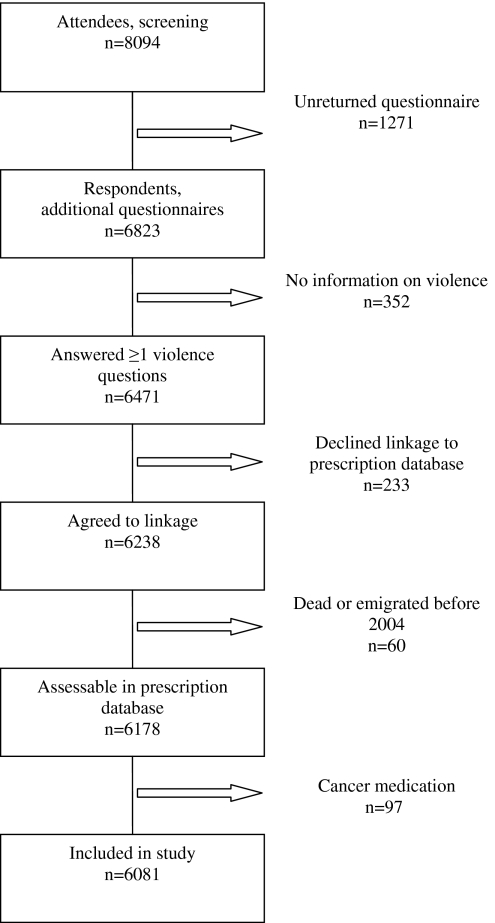

The Oslo Health Study was conducted under the joint collaboration of the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, the University of Oslo and the Municipality of Oslo. Details about the design, the questionnaires, the data collection and consent procedures are described previously, and information is available at the web page of the Norwegian Institute of Public Health.5 17 18 A main questionnaire and an invitation to attend a health screening were mailed to all citizens from selected birth cohorts. Additional questionnaires were distributed at the screening stations to be answered by the participants at home and returned by mail in a pre-paid envelope. The HUBRO questionnaires covered socio-demographics, current and past health, lifestyle, health service utilisation, medication use and life events. The additional questionnaires also included questions about violence and were addressed to women born in 1940, 1941, 1955, 1960 and 1970. Totally, 16 926 women in these age groups were invited to participate, of whom 8094 (48%) attended screening. Still, eligibility into our study required that women had answered at least one question about violence (figure 1). Furthermore, responders who died or emigrated before 2004 were excluded. Patients with reimbursement codes for cancer were also excluded since prescription for potentially addictive drugs is less restricted for them.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study sample selection.

Variables

Intimate partner violence

The study exposure variable was lifetime experiences of IPV. Violence was measured with five questions in HUBRO: (a) “Have you ever been systematically intimidated, degraded or humiliated over a longer period of time?” (b) “Have you ever experienced threats to harm you or someone close to you?” (c) “Have you ever been physically attacked/abused?” (d) “Have you ever been forced into sexual activities?” (e) “Has anyone ever raped you or tried to rape you?” Response alternatives were ‘No’, ‘Yes, below 18 years of age’ and ‘Yes, 18 years or above’. Each question (a)–(e) comprised separate questions about perpetrator (stranger, family/relative, partner, friend/acquaintance) and time of exposure (less vs more than 12 months ago). Violence was defined as IPV when the respondent reported their partner as perpetrator. Psychological abuse was defined as positive answers to question (a) and/or (b), physical violence as a positive response to question (c) and sexual violence as answered yes to question (d) and/or (e). IPV was classified as physical and/or sexual IPV if the woman answered yes to question c, d and/or e, as psychological IPV alone if she answered no to question (c)–(e) and yes to question a and/or b and no IPV (reference) if she answered no to all questions. The category physical and/or sexual IPV may also have included psychological abuse.

Prescriptions

The main outcome was prescriptions for potentially addictive drugs, including ATC codes N02A: Opioid analgesics; M03BA02: Carisoprodol; N05BA: Benzodiazepine anxiolytics; N05CD: Benzodiazepine hypnotics and N05CF: Benzodiazepine-related hypnotics (z-hypnotics). Opioid analgesics and the muscle relaxant Carisoprodol were classified as potentially addictive analgesics and benzodiazepine anxiolytics/hypnotics and z-hypnotics as CNS depressants. All drugs are classified as restricted by the Norwegian Medicines Agency.9

Other variables

Variables from HUBRO covered socio-demographics (age, education, paid employment, marital status and country of birth), lifestyle (daily cigarette smoking and alcohol use), medical history (chronic musculoskeletal pain, mental distress, sleep problems and use of potentially addictive drugs) and physical and/or sexual violence from other than partner as child and adult. Mental distress was assessed by the Hopkins Symptoms Checklist-10 (HSCL-10), which primarily covers symptoms of depression and anxiety during the previous week. It comprises 10 items scored on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). When three or more items were missing, mental distress was classified as missing. If one or two items were missing, they were replaced with the sample mean value for corresponding items. Mean score served as measure of mental distress and was dichotomised with cut-off at ≥1.85. HSCL-10 has displayed high psychometric qualities in population-based studies.19 Chronic musculoskeletal pain was defined as pain and/or stiffness in muscles and joints at least 3 months at a stretch last year and sleep problems as troubled by sleeplessness more than once a week. Use of potentially addictive drugs at baseline was recorded with an open question in HUBRO about drugs used in the previous 4 weeks. Women who reported trade names of potentially addictive drugs were defined as users at baseline.

Statistical analysis

Crude and multivariable-adjusted prescription rate ratios (RRs) were estimated with Poisson models with number of prescriptions as outcome. Due to overdispersion, we used the negative binomial models. Nearly half of the women did not receive any potentially addictive medicine, that is a large part with zero count, and if the Vuong test favoured a zero-inflated negative binomial model, we used this. The women were at risk for medicine prescriptions from 1 January 2004 until death/emigration or 31 December 2009. The logarithm of months of follow-up in NorPD was used as offset to allow for differing follow-up duration. The models included a priori defined covariates: model 1 adjusted for age, education, paid employment and marital status, while model 2 additionally included former chronic musculoskeletal pain, mental distress and sleep problems. Univariate associations between independent variables and drug use were examined with Pearson χ2 tests. Both univariable χ2 analyses and multivariable regression analyses were restricted to women with complete data on included variables. All statistical inferences were based on a two-sided significance level of 0.05. Analyses were performed with SPSS V.16.0 and STATA V.11.1 for Windows.

Results

The study included 6081 (75.1%) of 8094 women who attended screening (figure 1). Altogether 2013 were excluded: 1271 did not return the questionnaires, 352 answered no questions on violence, 233 declined linkages to NorPD, 60 died or emigrated before 2004 and 97 had prescriptions reimbursed due to cancer. Another 90 (1.5%) women died or emigrated during follow-up.

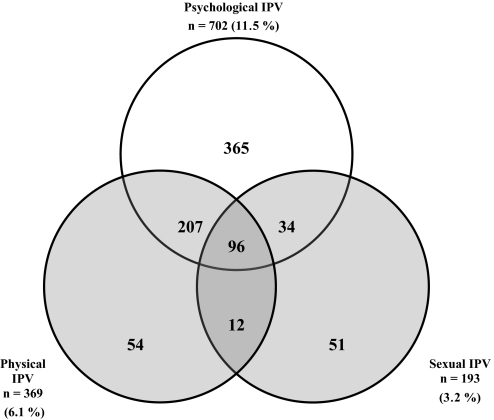

Figure 2 shows the distribution of women by type of IPV experiences. Totally, 819 (13.5%) women reported ever experiencing any type of IPV: 702 (11.5%) disclosed psychological IPV, 369 (6.1%) physical IPV and 193 (3.2%) sexual IPV. Among the 454 women who disclosed physical and/or sexual IPV, 337 (74.2%) also reported psychological IPV.

Figure 2.

Number and percentage of women who reported intimate partner violence (IPV) by type of violence. Totally 819 (13.5 %) of 6081 women reported ever experiencing any type of IPV. The grey area represents physical and/or sexual IPV (n=454) and the white area psychological IPV alone (n=365).

Table 1 displays characteristics of women and experiences of non-partner violence by exposure category. Both psychological IPV alone and physical/sexual IPV were more common in women who were middle aged, were divorced/separated, smoked cigarettes, reported mental distress and had chronic musculoskeletal pain. Furthermore, childhood and adult experiences of physical/sexual violence from someone other than their partner were more frequent among women who reported any IPV. In addition, women who had experienced physical/sexual IPV more often reported low education, no employment, frequent alcohol use and sleep problems.

Table 1.

Women's socio-demographic, lifestyle and health characteristics and experiences of non-partner violence by lifetime experiences of intimate partner violence (IPV) at enrolment, 2000/2001

| Characteristics | No IPV (n=5262) | Psychological IPV alone (n=365) | Physical/sexual IPV (n=454) | p Value* |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Age, n=6081 | ||||

| 30 | 1530 (29.1) | 93 (25.5) | 83 (18.3) | <0.001 |

| 40/45 | 2231 (42.4) | 191 (52.3) | 260 (57.3) | |

| 59/60 | 1501 (28.5) | 81 (22.2) | 111 (24.4) | |

| Education level, n=6032 | ||||

| Less than upper secondary | 745 (14.3) | 65 (18.0) | 95 (21.1) | <0.001 |

| Upper secondary | 1579 (30.3) | 105 (29.0) | 172 (38.1) | |

| College/university | 2895 (55.5) | 192 (53.0) | 184 (40.8) | |

| Paid employment, n=6030 | ||||

| Yes | 4425 (84.8) | 303 (83.9) | 337 (75.1) | <0.001 |

| No | 795 (15.2) | 58 (16.1) | 112 (24.9) | |

| Marital status, n=6080 | ||||

| Unmarried | 1866 (35.5) | 123 (33.8) | 127 (28.0) | <0.001 |

| Married | 2604 (49.5) | 94 (25.8) | 146 (32.2) | |

| Divorced/separated | 631 (12.0) | 143 (39.3) | 172 (37.9) | |

| Widowed | 161 (3.1) | 4 (1.1) | 9 (2.0) | |

| Country of birth, n=5620 | ||||

| Norway | 4185 (85.9) | 292 (88.5) | 365 (87.1) | 0.358 |

| Other | 686 (14.1) | 38 (11.5) | 54 (12.9) | |

| Daily cigarette smoking, n=6032 | ||||

| Yes | 1334 (25.6) | 157 (43.3) | 211 (46.6) | <0.001 |

| No | 3882 (74.4) | 206 (56.7) | 242 (53.4) | |

| Alcohol use, n=6046 | ||||

| 4–7 times a week | 259 (5.0) | 23 (6.3) | 34 (7.5) | 0.040 |

| Less | 4970 (95.0) | 341 (93.7) | 419 (92.5) | |

| Chronic musculoskeletal pain, n=5891 | ||||

| Yes | 1855 (36.4) | 156 (43.9) | 217 (49.2) | <0.001 |

| No | 3240 (63.6) | 199 (56.1) | 224 (50.8) | |

| Mental distress, n=5809 | ||||

| Yes | 521 (10.4) | 73 (21.2) | 117 (27.0) | <0.001 |

| No | 4510 (89.6) | 271 (78.8) | 317 (73.0) | |

| Sleep problems, n=6024 | ||||

| >1 weekly | 579 (11.1) | 48 (13.3) | 95 (21.0) | <0.001 |

| 1≤ weekly | 4630 (88.9) | 314 (86.7) | 358 (79.0) | |

| Childhood abuse†, n=6081 | ||||

| Yes | 462 (8.8) | 65 (17.8) | 104 (22.9) | <0.001 |

| No | 4800 (91.2) | 300 (82.2) | 350 (77.1) | |

| Other adult abuse†, n=6081 | ||||

| Yes | 371 (7.1) | 79 (21.6) | 114 (25.1) | <0.001 |

| No | 4891 (92.9) | 286 (78.4) | 340 (74.9) | |

Test of equality across the three categories of IPV experiences.

Physical and/or sexual violence by other than intimate partner.

Women who reported IPV were more frequently prescribed potentially addictive drugs, that is, analgesics as well as CNS depressants (table 2). The overall mean number of DDD was also higher among the group of women who had experienced IPV: 513 (95% CI 359 to 667) for sexual/physical IPV and 255 (95% CI 175 to 335) for psychological IPV alone compared with 144 (95% CI 127 to 161) among other women. Furthermore, women who reported IPV were more likely to obtain prescriptions for potentially addictive drugs from multiple (≥3) physicians.

Table 2.

Prescriptions for potentially addictive drugs by lifetime experience of intimate partner violence (IPV), 2004–2009

| Prescriptions | No IPV (n=5262) | Psychological IPV alone (n=365) | Physical/sexual IPV (n=454) | p Value* |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Potentially addictive drugs overall | ||||

| Any | 2767 (52.6) | 218 (59.7) | 308 (67.8) | <0.001 |

| Frequent† | 224 (4.3) | 30 (8.2) | 59 (13.0) | <0.001 |

| Potentially addictive analgesics | ||||

| Any | 2088 (39.7) | 169 (46.3) | 227 (50.0) | <0.001 |

| Frequent† | 244 (4.6) | 28 (7.7) | 60 (13.2) | <0.001 |

| CNS depressants | ||||

| Any | 1600 (30.4) | 137 (37.5) | 223 (49.1) | <0.001 |

| Frequent† | 224 (4.3) | 30 (8.2) | 64 (14.1) | <0.001 |

| Multiple prescribers (≥3)‡ | 791 (15.0) | 81 (22.2) | 133 (29.3) | <0.001 |

Test of equality across the three categories of IPV experiences.

Number of prescriptions ≥95 percentile of the study sample (potentially addictive drugs overall: ≥27 prescriptions; potentially addictive analgesics: ≥8 prescriptions; central nervous system (CNS) depressants: ≥18 prescriptions).

Total number of women who received prescriptions for potentially addictive drugs from three or more physicians.

The relationship between experiences of IPV and drug prescriptions was explored further in negative binomial regression models (table 3). Prescription rates were two times higher for women who reported psychological IPV alone and more than three times higher for those who reported physical/sexual IPV compared with those who did not report IPV. After adjustment for socio-demographics, prescription rates remained twice as high both for physical/sexual IPV and psychological IPV alone compared with other women (model 1). The association appeared consistent across analgesics and CNS depressants. Additional adjustments for prior chronic musculoskeletal pain, mental distress and sleep disorders sparsely reduced RRs (model 2).

Table 3.

Relationship between lifetime experiences of intimate partner violence (IPV) and prescriptions for potentially addictive drugs, 2004–2009

| No adjustments, n=6081 |

Model 1, n=5981* |

Model 2, n=5558/5813/5694† |

|||||||

| Prescriptions | Person-years | RR (95% CI) | Prescriptions | Person-years | RR (95% CI) | Prescriptions | Person-years | RR (95% CI) | |

| Potentially addictive drugs overall | |||||||||

| No IPV (ref.) | 26 118 | 31 332 | 1 | 25 714 | 30 828 | 1 | 23 190 | 28 650 | 1 |

| Psychological IPV alone | 3788 | 2166 | 2.13 (1.69 to 2.69) | 3758 | 2118 | 2.03 (1.63 to 2.53) | 3644 | 1956 | 1.97 (1.59 to 2.45) |

| Physical/sexual IPV | 7896 | 2692 | 3.57 (2.89 to 4.40) | 7802 | 2644 | 2.44 (2.00 to 2.97) | 7270 | 2471 | 1.83 (1.50 to 2.22) |

| Potentially addictive analgesics | |||||||||

| No IPV (ref.) | 11 603 | 31 332 | 1 | 11 430 | 30 828 | 1 | 11 009 | 29 945 | 1 |

| Psychological IPV alone | 1867 | 2166 | 2.37 (1.83 to 3.07) | 1862 | 2118 | 2.06 (1.61 to 2.64) | 1861 | 2070 | 2.10 (1.65 to 2.68) |

| Physical/sexual IPV | 3083 | 2692 | 3.11 (2.46 to 3.93) | 3034 | 2644 | 2.04 (1.64 to 2.55) | 2910 | 2572 | 1.92 (1.55 to 2.39) |

| CNS depressants | |||||||||

| No IPV (ref.) | 14 515 | 31 332 | 1 | 14 284 | 30 828 | 1 | 13 194 | 29 358 | 1 |

| Psychological IPV alone | 1921 | 2166 | 1.94 (1.41 to 2.67) | 1896 | 2118 | 2.11 (1.56 to 2.85) | 1835 | 1998 | 1.94 (1.44 to 2.61) |

| Physical/sexual IPV | 4813 | 2692 | 3.93 (2.95 to 5.23) | 4768 | 2644 | 2.83 (2.16 to 3.70) | 4534 | 2537 | 2.00 (1.53 to 2.61) |

Rate ratios (RRs) and CIs adjusted for age, education, employment and marital status.

RRs and CIs adjusted for age, education, employment, marital status and former symptoms (potentially addictive drugs overall, n=5558: adjusted for chronic musculoskeletal pain, mental distress and sleep problems; potentially addictive analgesics, n=5813: adjusted for chronic musculoskeletal pain; CNS depressants, n=5694: adjusted for mental distress and sleep problems).

At baseline (2000/2001), 620 (10.2%) women reported use of potentially addictive drugs last 4 weeks, of whom 550 (9.0%) also received prescriptions during follow-up. Drug use was more common among women who had experienced IPV: 22.9% for physical and/or sexual IPV and 14.3% for psychological IPV alone compared with 8.8% for other women. Prescription rates remained significantly higher for women who reported IPV even when women who used drugs at baseline were excluded: after model 2 adjustments prescription, RRs were 1.38 (1.10 to 1.72) for physical/sexual IPV and 1.55 (1.23 to 1.96) for psychological IPV alone.

Discussion

Women with lifetime experiences of IPV received prescriptions for potentially addictive drugs two to four times more frequently than other women. The increase applied to both potentially addictive analgesics and CNS depressants and remained significantly higher after multivariable adjustments.

A major strength of our study is the prospective and accurate measurement of drug prescriptions from a national register.15 It substantiates previous cross-sectional findings of increased medication use among women exposed to IPV5 6 11 14 and adds new evidence about restricted drugs with verified addictive potential. Our sample was enrolled from a large-scale survey with consent to link information to health registers. Loss to follow-up was therefore minor. While many former studies of IPV have recruited participants within health or legal services, the population-based design of the current study enabled inclusion of women regardless of help seeking. However, the participation rate in HUBRO was low. Individuals who were unmarried, had low socioeconomic status, non-Western origin and received disability pension were under-represented. Prevalence of IPV may therefore have been underestimated since IPV was associated with low socioeconomic status and poor health in former studies as well as our.1–4 Actually, our prevalence estimates were lower compared with a Norwegian national survey of IPV.2 The latter used a more comprehensive violence questionnaire with a potentially higher sensitivity than the more general questions on violence in HUBRO. Still, a study of potential non-participation bias in HUBRO found largely unbiased association estimates.17 Our estimates of associations between IPV and prescription of potentially addictive drugs might, however, have been affected by differential selection bias if the severity of IPV and the magnitude of drug use influenced the likelihood of participation. Furthermore, some women in the control group may have experienced IPV during follow-up. This would probably bias the estimates towards zero. Since our study was limited to women aged 30–60 years at baseline, the estimated association between IPV and prescription of potentially addictive drugs may not necessarily be valid for women in other age groups. Another limitation is the lack of prescription data between HUBRO in 2000/2001 until the establishment of NorPD in 2004. Despite the time lag, we cannot certify that IPV preceded drug use. However, prescription rates remained significantly increased when women who reported use of potentially addictive drugs in HUBRO were excluded from analyses. We did not assess all potentially addictive drugs; for example, CNS stimulants were not included since they were rarely prescribed for women in the eligible age categories.20

Prescription rates were highest among women who had experienced IPV comprising physical and/or sexual violence but were clearly higher for psychological IPV alone as well.

Most of the women who reported physical and/or sexual IPV had experienced multiple types of violence, including psychological abuse (figure 2). Stronger associations for physical and/or sexual IPV may therefore represent a cumulative effect. Furthermore, after adjustments for socio-demographic variables, the strengths of the associations were approximately equal (model 1). Thus, our findings consolidate the emerging evidence of a negative health impact of psychological IPV irrespective of whether it co-occurs with physical or sexual violence.5 14 21 Adjustment for chronic musculoskeletal pain, mental distress and sleep disorders at baseline sparsely reduced rate differences (model 2). There is generally little research on predictors for use of potentially addictive drugs. Previously suggested predictors include gender, age, ethnicity, employment, mental illness and certain physical diagnosis.22 Still, it is uncertain whether some variables should be considered as potential confounders or intermediate variables on a causal path between IPV and drug prescriptions.23 Overadjustment would occur if multivariable analysis included intermediate variables.24 Our analysis may also have missed relevant confounders. Nonetheless, we tested several potential socio-demographic and clinical confounders, yet the associations remained significant. The robust relationship between IPV and drug prescription underscores the contribution of IPV to the burden on women's health.

Potentially addictive drugs may help to relieve pain, anxiety and sleep disorders, which are all associated with IPV.1–4 The higher prescription frequency among women who reported IPV may therefore reflect a greater need of symptom relief. However, such drugs have many adverse side effects other than addiction, such as impaired psychomotor function, amnesia, vertigo, sedation, hyperalgesia, constipation, nausea, increased anxiety and higher risk of accidents.7 8 A combination with alcohol is particularly dangerous, and deliberate overdose is not uncommon.7 8 25 Furthermore, medical use of potentially addictive drugs is associated with non-medical use.26 Substance use disorders and suicidal attempts are associated with IPV1 4 12 27 and should be assessed before such drugs are prescribed.

We cannot evaluate the appropriateness of drug prescription or the occurrence of prescription drug abuse. Yet it may be of concern that women who reported IPV more often acquired their drugs from multiple physicians. This might be an indicator of prescription drug abuse.28 Furthermore, former studies have demonstrated that non-clinical factors such as time-saving and a feeling of inadequacy towards patients in difficult psychosocial situations influenced physicians' prescription.29 30 A survey among Norwegian General Practitioners also revealed that the vast majority had prescribed potentially addictive drugs, even though they doubted their benefit.31 We had no information if IPV was assessed among women in our study in connection with prescription. However, a study of rape survivors showed that the majority of those who received a prescription for sedatives and/or antidepressants did so without disclosing the assault.32 Moreover, women who received a prescription after they had told their physician about the rape, often felt troubled by the response. We have not found similar studies related to IPV, but it has been documented that few physicians identify IPV experiences.33

The context of drug prescription and physicians' recognition of IPV among women who have experienced IPV should be investigated in future studies. Our study was performed in an urban population of women in Norway, a country with universal healthcare. External validity may be limited by differences in how healthcare provision is organised and financed. Access to prescription drugs may depend more on personal economic means in countries with different kinds of insurance-based healthcare. It may also vary between urban and rural settings. Moreover, we did not have any data on IPV experiences among men. Similar studies should be performed in other countries and in rural settings and include both genders.

There is still a lack of evidence on favourable health service interventions to prevent IPV and its associated adverse health outcomes.34 35 However, recent findings indicate that a training and support programme for professionals in primary care may improve identification and access to help services of women who experience IPV.36 Physicians may use therapeutic relationships to identify violence, ensure appropriate medical care and initiate interventions to end violence. Yet many physicians unknowingly see and treat women living in violent relationships,37 thus it becomes a hidden and chronic health risk. Healthcare providers should be aware that women who have experienced any kind of IPV more frequently than others receive prescriptions for potentially addictive drugs. Researchers and clinicians should increase the awareness of the health consequences and psychosocial impact of such prescription, and focus on establishing evidence-based healthcare interventions for women who have experienced IPV.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The data collection was conducted as part of the Oslo Health Study 2000–2001 in collaboration with the Norwegian Institute of Public Health. We thank all respondents for participating.

Footnotes

To cite: Stene LE, Dyb G, Tverdal A, et al. Intimate partner violence and prescription of potentially addictive drugs: prospective cohort study of women in the Oslo Health Study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000614. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000614

Contributors: LES contributed to the design of the study, analysed and interpreted the data and wrote the report. GD contributed to the study design and the interpretation of the data. AT collaborated in the statistical analysis and data management. GWJ contributed to the study design and the interpretation of the data. BS, the principal investigator, conceived the study and designed the protocol. All authors participated in drafting of the report and approved the final version.

Funding: This study was funded by the Norwegian Research Council (grant number 185755/V50). The funding source had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report. The authors of this report are responsible for its content.

Competing interests: The authors have no competing interests to declare. All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author).

Patient consent: All participants gave written informed consent in the Oslo Health Study.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics and the Norwegian Data Inspectorate.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet 2002;359:1331–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nerøien AI, Schei B. Partner violence and health: results from the first national study on violence against women in Norway. Scand J Public Health 2008;36:161–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ellsberg M, Jansen H, Heise L, et al. ; WHO Multi-country Study on Women's Health and Domestic Violence against Women Study Team Intimate partner violence and women's physical and mental health in the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence: an observational study. Lancet 2008;371:1165–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coker AL, Davis KE, Arias I, et al. Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. Am J Prev Med 2002;23:260–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stene LE, Dyb G, Jacobsen GW, et al. Psychotropic drug use among women exposed to intimate partner violence: a population-based study. Scand J Public Health 2010;38(5 Suppl):88–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romans SE, Cohen MM, Forte T, et al. Gender and psychotropic medication use: the role of intimate partner violence. Prev Med 2008;46:615–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benyamin R, Trescot AM, Datta S, et al. Opioid complications and side effects. Pain Physician 2008;11(Suppl 2):S105–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lader MH. Limitations on the use of benzodiazepines in anxiety and insomnia: are they justified? Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 1999;9(Suppl 6):S399–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rønning M, Berg C, Furu K, et al. The Norwegian Prescription Database 2005–2009. Norwegian Institute of Public Health. Report number: 2, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manchikanti L. National drug control policy and prescription drug abuse: facts and fallacies. Pain Physician 2007;10:399–424 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wuest J, Merritt-Gray M, Lent B, et al. Patterns of medication use among women survivors of intimate partner violence. Can J Public Health 2007;98:460–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cole J, Logan TK. Nonmedical use of sedative-hypnotics and opiates among rural and urban women with protective orders. J Addict Dis 2010;29:395–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plichta SB. Intimate partner violence and physical health consequences: policy and practice implications. J Interpers Violence 2004;19:1296–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshihama M, Horrocks J, Kamano S. The role of emotional abuse in intimate partner violence and health among women in Yokohama, Japan. Am J Public Health 2009;99:647–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Furu K. Establishment of the nationwide Norwegian Prescription Database (NorPD) - new opportunities for research in pharmacoepidemiology in Norway. Nor J Epidemiol 2008;18:129–36 [Google Scholar]

- 16.WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology Guidelines for ATC Classification and DDD Assignment 2005. Oslo, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Søgaard AJ, Selmer R, Bjertness E, et al. The Oslo Health Study: the impact of self-selection in a large, population-based survey. Int J Equity Health 2004;3:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Søgaard AJ, Selmer R. The Oslo Health Study. 2006. http://www.fhi.no/dav/bbb2a86ad7.doc (accessed 12 Sep 2011).

- 19.Strand BH, Dalgard OS, Tambs K, et al. Measuring the mental health status of the Norwegian population: a comparison of the instruments SCL-25, SCL-10, SCL-5 and MHI-5 (SF-36). Nord J Psychiatr 2003;57:113–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norwegian Institute of Public Health 2011. http://www.norpd.no/Prevalens.aspx (accessed 10 Aug 2011).

- 21.Ludermir AB, Lewis G, Valongueiro SA, et al. Violence against women by their intimate partner during pregnancy and postnatal depression: a prospective cohort study. Lancet 2010;376:903–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simoni-Wastila L. The use of abusable prescription drugs: the role of gender. J Womens Health Gend Based Med 2000;9:289–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brookhart MA, Stürmer T, Glynn RJ, et al. Confounding control in healthcare database research: challenges and potential approaches. Med Care 2010;48(Suppl 6):S114–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schisterman EF, Cole SR, Platt RW. Overadjustment bias and unnecessary adjustment in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiology 2009;20:488–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prescott K, Stratton R, Freyer A, et al. Detailed analyses of self-poisoning episodes presenting to a large regional teaching hospital in the UK. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2009;68:260–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fenton MC, Keyes KM, Martins SS, et al. The role of a prescription in anxiety medication use, abuse, and dependence. Am J Psychiat 2010;167:1247–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Devries K, Watts C, Yoshihama M, et al. Violence against women is strongly associated with suicide attempts: evidence from the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence against women. Soc Sci Med 2011;73:79–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pauly V, Frauger E, Pradel V, et al. Which indicators can public health authorities use to monitor prescription drug abuse and evaluate the impact of regulatory measures? Controlling High Dosage Buprenorphine abuse. Drug Alcohol Depend 2011;113:29–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bjørner T, Laerum E. Factors associated with high prescribing of benzodiazepines and minor opiates. A survey among general practitioners in Norway. Scand J Prim Health Care 2003;21:115–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anthierens S, Habraken H, Petrovic M, et al. The lesser evil? Initiating a benzodiazepine prescription in general practice: a qualitative study on GPs' perspectives. Scand J Prim Health Care 2007;25:214–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vevatne T, Selbekk AS, Sand R. [Addictive drugs prescription practice among general practitioners] (In Norwegian). Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2010;130:1925–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sturza ML, Campbell R. An exploratory study of rape survivors' prescription drug use as a means of coping with sexual assault. Psychol Women Q 2005;29:353–63 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elliott L, Nerney M, Jones T, et al. Barriers to screening for domestic violence. J Gen Intern Med 2002;17:112–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wathen CN, MacMillan HL. Interventions for violence against women: scientific review. JAMA 2003;289:589–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacMillan HL, Wathen CN, Jamieson E, et al. Screening for intimate partner violence in health care settings: a randomized trial. JAMA 2009;302:493–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feder G, Davies RA, Baird K, et al. Identification and Referral to Improve Safety (IRIS) of women experiencing domestic violence with a primary care training and support programme: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2011;378:1788–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soglin LF, Bauchat J, Soglin DF, et al. Detection of intimate partner violence in a general medicine practice. J Interpers Violence 2009;24:338–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.