Abstract

Objective

Vascular Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (vEDS) is a rare genetic condition related to mutations in the COL3A1 gene, responsible of vascular, digestive and uterine accidents. Difficulty of clinical diagnosis has led to the design of diagnostic criteria, summarised in the Villefranche classification. The goal was to assess oral features of vEDS. Gingival recession is the only oral sign recognised as a minor diagnostic criterion. The authors aimed to check this assumption since bibliographical search related to gingival recession in vEDS proved scarce.

Design

Prospective case–control study.

Setting

Dental surgery department in a French tertiary hospital.

Participants

17 consecutive patients with genetically proven vEDS, aged 19–55 years, were compared with 46 age- and sex-matched controls.

Observations

Complete oral examination (clinical and radiological) with standardised assessment of periodontal structure, temporomandibular joint function and dental characteristics were performed. COL3A1 mutations were identified by direct sequencing of genomic or complementary DNA.

Results

Prevalence of gingival recession was low among patients with vEDS, as for periodontitis. Conversely, patients showed marked gingival fragility, temporomandibular disorders, dentin formation defects, molar root fusion and increased root length. After logistic regression, three variables remained significantly associated to vEDS. These variables were integrated in a diagnostic oral score with 87.5% and 97% sensitivity and specificity, respectively.

Conclusions

Gingival recession is an inappropriate diagnostic criterion for vEDS. Several new specific oral signs of the disease were identified, whose combination may be of greater value in diagnosing vEDS.

Article summary

Article focus

To provide physicians with an in-depth description of oral involvement of patients with vEDS.

To evaluate specificity of gingival recession, a minor diagnostic criterion for vEDSin the Villefranche classification.

Key messages

Prevalence of gingival recession and periodontitis was low among patients with vEDS.

Conversely, patients showed marked gingival fragility, temporomandibular joint disorders, dentin formation defects, molar root fusion and increased root length.

Several new specific oral signs of this disease were identified, whose combination may be of greater diagnostic value.

Strengths and limitations of this study

All screened patients had genetically confirmed vEDS.

Limited sample size, sex ratio imbalance, pre-adult patients were not included. Validation studies are necessary.

Introduction

Vascular Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (vEDS OMIM#130050) is a rare genetic condition with an estimated prevalence of 1/150 000.1 Its clinical course is the most severe among the Ehlers–Danlos syndromes (EDSs). The inheritance of vEDS follows an autosomal dominant trait and is related to mutations in the COL3A1 gene, encoding the pro-α (1) chain of type III procollagen.1 The mutation typically alters the assembly, stability and thus secretion and resistance to tensile stress of this fibrillar collagen, resulting in early spontaneous arterial, digestive and obstetrical accidents. Over 250 different mutations have been described in the COL3A1 gene, typically either missense mutations affecting a glycine residue, splicing mutations or rare exonic deletions.2 No genotype–phenotype correlations have been evidenced, except for haploinsufficiency, which may be characterised by a consistently milder phenotype.3

Oral involvement is frequently present in patients with vEDS, even in early adulthood, described as gingival recession.4 This oral sign of the disease, despite being part of the minor diagnostic criteria of the Villefranche classification4 remains poorly documented and no in-depth description of the proposed occurrence of gingival recession in the vEDS diagnostic criteria was found in previously published reports.

In this study, we aimed to reassess oral involvement in a cohort of patients with molecularly proven vEDS (ie, with proven COL3A1 mutations). We hypothesised that a systematic assessment of dental, gingival and osteoarticular characteristics of these patients would show significant differences with age- and sex-matched controls.

Methods

Study design

This study was designed according to guidelines of the STROBE statement. Consecutive patients with molecularly proven vEDS and healthy volunteers were prospectively included in a monocentric case–control study. Each patient was appointed for a routine dental visit. Detailed standardised clinical records on teeth and surrounding soft tissues were made by a senior dental surgeon. Most of the time, physicians were aware of the patient's diagnostic status upon inclusion except for patients that were in diagnostic work-up with genetic testing in progress. Standardised dental x-rays were performed for each subject which included periapical x-rays of the upper and lower jaws for detection of root and surrounding bone structure, positional assessment of emerged and emerging teeth and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) imaging by orthopantomogram (OPG). Intra-oral pictures were made for all patients. All examinations were performed for clinical care and diagnostic purpose.

Study population

Patients with genetically diagnosed vEDS from the Centre de Référence des Maladies Vasculaires Rares (Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou, Assistance Publique des Hôpitaux de Paris, Paris, France), the French National Referral Centre for patients with vEDS, were sent to the Dental Department of Albert Chenevier Henri-Mondor University Hospital for dental care. Patients with suspected vEDS referred for dental status assessment without mutation in the COL3A1 gene were excluded of the study after screening. The control group was constituted by random inclusion of consecutive healthy subjects that consulted the dental department for clinical care. Control subjects had no medical history, especially no suspicion of connective tissue disorder and were referred for general dentistry purposes. Patients of the control group were age and sex matched with the vEDS patients in a ratio close to 3 to 1. To limit the possibility of confounders of gingival bleeding or temporomandibular disorders, three common oral indexes were measured at baseline: plaque index, gingival index and decayed/missing/filled teeth index.

Medical and genetical data

Patients included in this study were clinically assessed by senior physicians of the French referral centre for rare vascular diseases (see above). Patient history and clinical characteristics of vEDS were systematically assessed by a standardised observation. Number and type of vascular, digestive and uterine complications were recorded. Major and minor clinical diagnostic criteria were staged according to the Villefranche classification.4 Genomic DNA was obtained by saline extraction from whole blood leucocytes. The COL3A1 gene was then analysed by direct sequencing as previously described.5 In case of negative direct DNA sequencing, patients were screened for exon skipping by fibroblast culture, RNA extraction, reverse transcription and PCR and direct sequencing.5 All patients gave written informed consent. Mutations are described according to the nomenclature recommended by the Human Genome Variation Society. DNA mutation numbering was based on COL3A1 human complementary DNA sequence (GenBank NM_000090.3).

Oral examination

Periodontal status

The periodontal data consisted in standardised measurement of gingival fragility, thickness, recession and surface texture. Fragility and bleeding tendency was assessed by a periodontal probe and staged according to Loe classification.6 History of gingival bleeding and its frequency during tooth brushing as described by the patient was recorded. Gingival thickness was measured by the ability to see the graded periodontal probe through gingival tissue.7 Recessions of the gingival margin in respect of the cementoenamel junction were measured at six different sites per tooth. The gum surface texture (stippling) was assessed visually and evaluated qualitatively. Diagnosis of periodontitis was checked clinically and radiologically. Periodontal pockets were evaluated by probing, and alveolar bone level was assessed by x-rays in order to detect horizontal and angular bone loss.

Dental status

Teeth were clinically and radiologically assessed for structural abnormalities and secondary lesions (decay, traumatic injury…), as well as root fusion and pulp volume, defined by the pulp to crown area ratio as measured on retroalveolar x-rays. Root length of mandibular teeth was defined as normal when stopping before the upper limit of the mandibular canal, which is easily visible on the OPG, and as long when crossing it.

TMJ status

History of oro-facial pain originating either from the masticatory muscles or the joint capsula was recorded, including reports of pain in the jaw, temples, face, pre-auricular area or the TMJ both at rest and in function. Physical examination included the observation and measurements of mandibular motion (maximal interincisal opening, lateral movements and protrusion), palpation of the masticatory muscles (masseter, temporalis, medial and lateral pterygoid muscles) and static and dynamic TMJ palpation. During mandibular motions, noises were staged as follows: ‘clicking’, ‘popping’ as a consequence of disk displacement and ‘crunching’, ‘grating’ and/or ‘grinding’ as a consequence of osteoarthritis. Joint surfaces were studied on OPGs, in search of extensive flattening or sclerosis of the articular surfaces. TMJ disorders were then staged according to validated international guidelines (Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporo-Mandibular Disorders, RDC/TMD) as previously described by Dworkin and LeResche.8 Briefly, three groups are individualised by this classification: muscle disorders (group 1), disk displacements (group 2) and arthralgia/arthritis/arthrosis (group 3). These clinical indicators allow a stratification of TMD for each subject, for each group may be present separately or in association with one other.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics used numbers and percentages for qualitative variables and median and inter-quartiles ranges intervals for quantitative ones. The comparison between groups was performed using χ2 tests or Fisher's exact tests for qualitative variables and two-sample Wilcoxon tests for quantitative ones. Variables with a p value <0.10 in the first step were then entered in a stepwise logistic regression. Variables with a p value <0.06 using the Wald test were retained in the final model. A simplified diagnostic score with five levels was built from the results of the logistic model. The receiver operating characteristic curve of this simplified diagnostic score was computed, a threshold was determined and sensitivity and specificity were evaluated using this threshold, with their exact 95% CIs. All the tests were two sided, with a p value considered significant when <0.05. All the computations were performed using the SAS® V.9.2 statistical package (SAS Institute Inc.).

Results

Participants

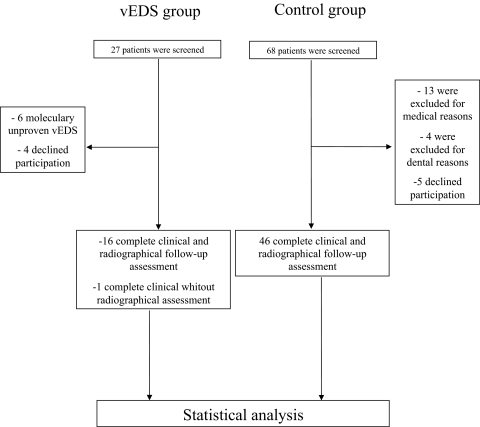

Between November 2009 and June 2011, 27 consecutive patients with suspected or confirmed vEDS were referred for dental examination. Patients without genetic confirmation of vEDS (n=6) were not considered eligible for participation. Of the 21 remaining patients, four declined participation and 17 were finally included (figure 1). In one patient, OPG was unavailable and therefore excluded from the design of the oral score. Control subjects (n=68) were screened for an inclusion ratio of 3 to 1. Five subjects declined participation and 17 were considered ineligible for medical reasons (ie, pregnancy, diabetes…) or dental status (full edentulous or severe periodontitis), leaving 46 controls that completed the study. Baseline characteristics of vEDS patients and controls are shown in table 1. Dental status of vEDS and control patients were equivalent as shown by the decayed/missing/filled teeth index. The plaque and gingival indexes, source of confounding biases in specificity of gingival bleeding, did not differ significantly between both groups.

Figure 1.

Flow chart.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with vEDS and age- and sex-matched healthy controls

| Variable | vEDS patients, n (%) or median (Q1; Q3) | Controls, n (%) or median (Q1; Q3) | Univariate p value |

| N | 17 | 46 | |

| Age | 33 (24; 44) | 36 (25; 45) | NS |

| Male | 5 (29) | 13 (28) | NS |

| Periodontal features | |||

| Plaque index | 30 (20; 54) | 20 (13; 60) | NS |

| Gingival index | 1 (0; 1) | 1 (0; 1) | NS |

| Probing bleeding index | 2 (1; 3) | 1 (0; 1) | 0.0003 |

| Thinness | 16 (94) | 20 (43) | 0.0003 |

| Temporomandibular features | |||

| TMJ group 1 | 2 (12) | 2 (4) | NS |

| TMJ group 2 | 12 (71) | 8 (17) | <0.0001 |

| TMJ group 3 | 10 (59) | 3 (7) | 3.10−5 |

| Total TMJ | 14 (82) | 11 (24) | <0.0001 |

| Pain | 7 (41) | 3 (100) | NS |

| Dental features | 15 (94) | 23 (50) | 0.0020 |

| Pulp shape modification | 12 (75) | 14 (30) | 0.0019 |

| Root fusion | 8 (50) | 9 (20) | 0.0262 |

| Exceeding root length | 11 (69) | 1 (2) | 10−7 |

| DFMT | 4 (2; 11) | 7 (2; 9) | NS |

Plaque index is defined by (number of tooth with plaque/total number of tooth) ×100. Gingival index is defined by extent of gingival inflammation and staged from 0 to 3. DMF-T index9 is defined by decayed, missing and filled teeth, and ranges from 0 to 28 according to number of diseased teeth.

DMF-T, ‘decayed/missing/filled teeth index’; TMJ, temporomandibular joint; vEDS, vascular Ehlers–Danlos syndrome.

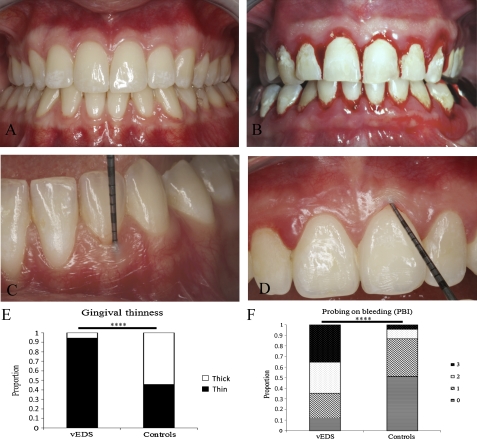

Periodontal status

Gingival recession was less frequent in patients (n=7; 41.2%) than in controls (n=31; 67.3%). Periodontitis was present in 23.5% (n=4) vEDS patients only when compared with controls (n=21; 45%). Presentation of gingiva in vEDS patients was evocative of a particular periodontal phenotype rather than common dental or periodontal disease. This phenotype was characterised by a generalised thinness of both gingiva and oral mucosa and translucency of the gingiva with apparent vasculature (figure 2A,C). Overall, increased gingival thinness was present in 16 (94%) patients versus 20 (43.3%) controls. Gingival surface texture was also evocative, with a decreased stippling and a papyraceous aspect when pressuring the gum with the dental probe (figure 2D). These characteristics were associated with an increase in gingival fragility, as measured by bleeding on probing during gingival thinness assessment (figure 2B,F and table 1).

Figure 2.

Periodontal characteristics of vascular Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (vEDS). Both gingival and oral mucosa appear very thin (A). Oral mucosa showed signs of spontaneous intramucosal bleeding as a likely consequence of increased fragility. Periodontal probing provoked excessive gingival bleeding (B). Assessment of gingival thinness was made by measuring levels of translucency on a scaled probe (C). Papyraceous aspect of the gingival tissue under periodontal probe pressure and decreased stippling (D). Comparison of gingival thinness (E) and gingival bleeding on probing (F) in patients with vEDS and healthy controls. ****p<0.001.

TMJ status

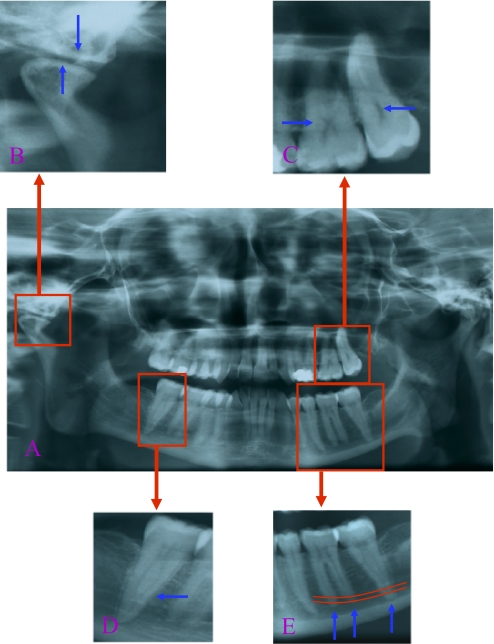

TMJ disorders were present in 14 (82%) patients with vEDS and in 11 (24%) controls (p<0.0001) (table 1). Almost half of patients (41%) described TMJ pain, whereas it was reported in only three (6.5%) controls. Pain originated from the masticatory muscles or the TMJ itself (groups 1 and 3 in the TMD classification8) and were described as a discomfort during mastication or yawning. Seventy-one per cent of the vEDS patients presented significant intra-articular disc displacement with reduction associated to clicking (group 2). Premature remodelling of the TM articular surfaces (figure 3B) was present in seven of 16 (43.8%) patients, versus two (4.3%) in controls (p=0.0086). This last finding was highly prevalent in vEDS patients, whereas it was uncommon in controls.

Figure 3.

Oral radiographic characteristics of vascular Ehlers–Danlos syndrome. An orthopantogram of a 30-year-old patient shows original dental findings (A) as premature remodelling of temporomandibular joints (B), decreased pulp volume, a thistle-shaped pulp chamber (C), an increased length of mandibular molar roots (D) and root fusion of the second mandibular molar (E).

Dental findings

Dental abnormalities observed in patients with vEDS were related to defects in dentin formation rather than to common dental pathology (table 1). x-Ray analysis revealed a significant reduction in pulp volume (figure 3C) secondary to progressive pulp obliteration by dentin synthesis. Pulpar volume decreases physiologically with ageing in the general population,10 yet it was repeatedly observed in young vEDS patients of this cohort. Furthermore, 75% of vEDS patients presented retraction of the dental pulp shape versus 29.8% of controls (table 1). Molar root fusion was also more frequently present, particularly in the mandibular second molar (50%) (figure 3D) when compared with controls (19.5%).

Mandibular dental root length was significantly increased in a large proportion of vEDS patients. Increased root length was most often found on the second mandibular molar (n=11/16), whereas such an observation was only exceptional in controls (n=1/46), more rarely on mandibular premolars or the first molar. This sign is very easily identifiable by any physician on the OPG (figure 3E).

Oral score

Three oral characteristics remained significantly associated to vEDS after logistic regression: increased root length, modified dental pulp shape and arthralgia/arthrosis (TMJ disorder group 3). These variables were staged into a diagnostic score according to results of the logistic model (table 2): increased root length was weighted 2 and the two remaining variables were weighted 1. Signs were either present (scoring either 1 or 2) or not (scoring 0). The total score is the result of adding weighted values of present signs. A score of 0 or 1 was considered negative and a score of 2 to 4 was considered positive with a sensitivity and specificity of 0.878 95% CI (0.604 to 0.978) and 0.978 95% CI (0.870 to 0.999%), respectively (table 2 and supplemental data 2).

Table 2.

Oral signs significantly associated to vascular Ehlers–Danlos syndrome after logistic regression and the deducted oral score

| Variable | Parameter estimate | OR (95% CI) | p Value |

| Intercept | −4.7 | ||

| TMJ-D group 3 | 3.4 | 29.5 (2.2 to 389.6) | 0.0101 |

| Pulp shape modification | 2.6 | 14.0 (1.0 to 193.8) | 0.0488 |

| Increased root length | 5.5 | 256.1 (9.5 to >999.9) | 0.0009 |

| Oral score | ||

| A. TMJ group 3 | No (0) | Yes (1) |

| B. Pulp shape modification | No (0) | Yes (1) |

| C. Exceeding root length | No (0) | Yes (2) |

Oral score (A+B+C): if score =0 or 1, negative result and if score >1, positive result.

TMJ-D, temporomandibular joint disorder.

Discussion

This case-control study is the first specific report of oral phenotype in patient with genetically confirmed vEDS. We evidenced that gingival recession may be an inappropriate diagnostic criterion of vEDS, whereas several other original findings may be of greater diagnostic value: increased dental root length, TMJ pain and premature arthrosis and a decreased pulp to crown area ratio. The first two criteria are easily identifiable by any physician on an OPG and on physical examination. The third requires either a short-specific training on reading retro-alveolar x-rays, or a specific, but simple evaluation by a dental surgeon.

Oral mucosa and gingival thinness have to be considered as an aspect of the general phenotype of vEDS. Indeed, typical skin involvement is marked by increased thinness with consequent translucency11 and by increased fragility, illustrated by the occurrence of extensive spontaneous haematomas and delayed papyraceous wound healing. A decreased intima-media thickness of elastic arteries in vEDS may be another phenotypic expression.12 Similarly to the skin, type III collagen is present in the gingival connective tissue near the basement membrane and blood vessels.11 Consequently, the disturbance of type III collagen production/secretion by the gingival fibroblast population, besides the physical and thermal stress the gum is exposed to and which may alter type III collagen,13 may explain in part the increase of gingival thinness14 15 and thus its fragility and bleeding tendency. Possible involvement of type III collagen in platelet adhesion would be a further precipitating factor for bleeding.16

Dental abnormalities and particularly radicular abnormalities as increased root length that has been repeatedly evidenced in ours patients may be specific for the disease. Indeed, this condition is exceptional in the general population, so, its random finding would have been unlikely in the vEDS group. Type III collagen is necessary to type I collagen fibrillogenesis.17 Other collagen gene mutations are reported to be associated with oral and dental abnormalities: type I collagen chain gene mutations are associated with type I dentinogenesis imperfecta in the more general context of osteogenesis imperfecta.18 In this case, the teeth are specifically amber and translucent. Radiographically, the teeth have short, constricted roots and dentine hypertrophy leading to pulpal obliteration.18 These diverse structural defects highlight the key-role of fibrillar collagens in mineralised tissue formation. An abnormal type III collagen in dental and articular tissues may also explain the dental and TMJ abnormalities/disorders. Its presence within dentin remains controversial, yet it has been evidenced in the epithelio-mesenchymal interface during dentinogenesis.19 Finally, type III collagen has been evidenced in the posterior region of disc attachments of the TMJ.20

Previous studies have reported diverse oral signs in EDS patients but none were specific to vEDS and none were dedicated to a cohort of patients with molecularly confirmed vEDS.21 The absence of genetic certainty is a major selection bias as the disease may be confused with other connective tissue diseases as non-vascular EDSs or more recently evidenced Loeys–Dietz syndrome.11 Periodontal or oral lesions were recorded in several studies on patients with various non-vascular subtypes of EDS, but no significant association between oral signs and EDS subtype could be evidenced.22–26 The only study reporting oral signs as a possible diagnostic tool in EDSs was related to the classical (OMIM#130020) and hypermobile (OMIM#130000 and OMIM#130010) types.27 It was suggested that absence of the inferior lingual and labial frenulas were specific and sensitive signs for these forms of EDS, yet these results have been subject to controversy.28 In our population sample, frenulas were absent in approximately one-third of patients.

This study has several limitations. First, our analysis is based on a small number of patients. However, this limited population sample has to be considered in respect of the rarity of vEDS, as it is to our best knowledge the most important clinical study of oral involvement of the disease. Second, the sex ratio is unbalanced which may induce selection bias, notably for gingival thinness that is more common in women in the general population.7 However, there is no evidence that oral signs of vEDS identified by logistic regression may be influenced by sex ratio. Furthermore, patients were assigned age- and sex-matched controls that may further limit any residual bias. Finally, no children or teenagers were included into this study. It is therefore not known if these findings may apply to this specific age category, which is of importance as typically the late teenage years match with the onset of digestive and arterial accidents in vEDS.

The oral score we were able to design may be of interest for clinical diagnosis of vEDS, especially as the phenotype is usually discrete and as diagnosis may be difficult even for experienced physicians.

Given its high specificity and sensitivity if it were to be confirmed, its diagnostic value as a minor diagnostic criterion as defined by the Villefranche classification should be evaluated. A positive oral score associated with one major vEDS sign may indicate genetic testing of the COL3A1 gene with a good positive predictive value. Further larger studies are necessary to determine the exact diagnostic value of gingival thinness and bleeding tendency in vEDS, as these signs were present in most patients, yet not independent predictors in our analysis. Considering the small number of vEDS patients, associations between mutation type and oral score were not tested (table 3). But interestingly, the two patients with a negative oral score had the same mutation type: an arginine substitution for glycine (table 3). This observation needs further explorations.

Table 3.

Type of COL3A1 mutation, first major complication and oral score of the 17 patients with vascular Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (vEDS)

| Patient | Age (years) | Sex (M/F) |

COL3A1 mutation |

First major complication | Oral score | |

| DNA | Protein | |||||

| 1 | 49 | F | c.665G>A | p.Gly222Asp | U | 4 |

| 2 | 30 | F | c.2285G>A | p.Gly762Asp | V | NA |

| 3 | 23 | M | c.575G>A | p.Gly192Asp | D | 3 |

| 4 | 46 | F | c.575G>A | p.Gly192Asp | D | 2 |

| 5 | 19 | F | c.1241G>T | p.Gly414Val | V | 4 |

| 6 | 44 | F | c.647G>C | p.Gly216Ala | U | 4 |

| 7 | 33 | F | c.1662+1G>A | exon 23 skipping | D | 4 |

| 8 | 20 | F | c.3364−2A>G | exon 46 skipping | N | 3 |

| 9 | 55 | F | c.755G>T | p.Gly252Val | U | 4 |

| 10 | 20 | F | c.755G>T | p.Gly252Val | N | 3 |

| 11 | 37 | M | c.952-106_996+45delinsGCTTAA | exon 14 skipping | V | 2 |

| 12 | 40 | F | c.951+1G>A | exon 13 skipping | V | 3 |

| 13 | 24 | F | c.1662+1G>A | exon 23 skipping | V | 2 |

| 14 | 34 | M | c.2150G>A | p.Gly717Asp | V | 2 |

| 15 | 24 | F | c.898−1G>C | exon 13 skipping | V | 2 |

| 16 | 50 | M | c.2671G>A | p.Gly891Arg | V | 0 |

| 17 | 29 | M | c.1330G>A | p.Gly444Arg | V | 1 |

The independent oral variables associated to vEDS were integrated into an oral score and each significant variable weighted according to the significance of the statistical association.

D, digestive; F, female; M, male; N, none; U, uterine; V, vascular.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that gingival retraction, used in the Villefranche classification, may be an inappropriate diagnostic criterion for vEDS and that increased root length, modified dental pulp shape and premature wear of TMJ are significantly associated to vEDS. These findings, if confirmed, may implement the latter in a diagnostic oral score for vEDS.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

To cite: Ferré FC, Frank M, Gogly B, et al. Oral phenotype and scoring of vascular Ehlers–Danlos syndrome: a case–control study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000705. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000705

Contributors: FCF, MF, BG and BPJF conceived and planned the study. MF, JE and XJ recruited the vEDS patients, FCF, BG and BPJF made the dental observations for all subjects, LG performed the statistical analysis; FCF, MF, BPJF, FG, AB, LG, AN and HC critically reviewed and interpreted the data and results; FCF, MF and BPJF wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the final version.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: This study occurred during routine dental observations. This is an observational study without intervention. There is no registration for this kind of study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no unsharing supplemental data.

References

- 1.Pepin M, Schwarze U, Superti-Furga A, et al. Clinical and genetic features of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV, the vascular type. N Engl J Med 2000;342:673–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Germain DP. Clinical and genetic features of vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Ann Vasc Surg 2002;16:391–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leistritz DF, Pepin MG, Schwarze U, et al. COL3A1 haploinsufficiency results in a variety of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV with delayed onset of complications and longer life expectancy. Genet Med 2011;13:717–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beighton P, De Paepe A, Steinmann B, et al. Ehlers-Danlos syndromes: revised nosology, Villefranche, 1997. Ehlers-Danlos national Foundation (USA) and Ehlers-Danlos Support group (UK). Am J Med Genet 1998;77:31–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pepin MG, Byers PH. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV. 1999 Sep 2 [Updated 3 May 2011]. In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, et al., eds. GeneReviewsTM [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loe H. The gingival index, the plaque index and the Retention index Systems. J Periodontol 1967;38(Suppl):610–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Rouck T, Eghbali R, Collys K, et al. The gingival biotype revisited: transparency of the periodontal probe through the gingival margin as a method to discriminate thin from thick gingiva. J Clin Periodontol 2009;36:428–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dworkin SF, LeResche L. Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: review, criteria, examinations and specifications, critique. J Craniomandib Disord 1992;6:301–55 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anonymous. Public health weekly reports for September 23, 1938. Public Health Rep 1938;53:1685–732 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morse DR. Age-related changes of the dental pulp complex and their relationship to systemic aging. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1991;72:721–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Germain DP. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2007;2:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boutouyrie P, Germain DP, Fiessinger JN, et al. Increased carotid wall stress in vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Circulation 2004;109:1530–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson DW, Thakker-Varia S, Tromp G, et al. A glycine (415)-to-serine substitution results in impaired secretion and decreased thermal stability of type III procollagen in a patient with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV. Hum Mutat 1997;9:62–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Byers PH, Holbrook KA, Barsh GS, et al. Altered secretion of type III procollagen in a form of type IV Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Biochemical studies in cultured fibroblasts. Lab Invest 1981;44:336–41 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith LT, Schwarze U, Goldstein J, et al. Mutations in the COL3A1 gene result in the Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV and alterations in the size and distribution of the major collagen fibrils of the dermis. J Invest Dermatol 1997;108:241–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Massberg S, Gawaz M, Gruner S, et al. A crucial role of glycoprotein VI for platelet recruitment to the injured arterial wall in vivo. J Exp Med 2003;197:41–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu X, Wu H, Byrne M, et al. Type III collagen is crucial for collagen I fibrillogenesis and for normal cardiovascular development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997;94:1852–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barron MJ, McDonnell ST, Mackie I, et al. Hereditary dentine disorders: dentinogenesis imperfecta and dentine dysplasia. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2008;3:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bronckers AL, Lyaruu DM, Woltgens JH. Immunohistochemistry of extracellular matrix proteins during various stages of dentinogenesis. Connect Tissue Res 1989;22:65–70 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gage JP, Virdi AS, Triffitt JT, et al. Presence of type III collagen in disc attachments of human temporomandibular joints. Arch Oral Biol 1990;35:283–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Coster PJ, Martens LC, De Paepe A. Oral health in prevalent types of Ehlers-Danlos syndromes. J Oral Pathol Med 2005;34:298–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linch DC, Acton CH. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome presenting with juvenile destructive periodontitis. Br Dent J 1979;147:95–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ooshima T, Abe K, Kohno H, et al. Oral manifestations of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type VII: histological examination of a primary tooth. Pediatr Dent 1990;12:102–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pope FM, Komorowska A, Lee KW, et al. Ehlers Danlos syndrome type I with novel dental features. J Oral Pathol Med 1992;21:418–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karrer S, Landthaler M, Schmalz G. Ehlers-Danlos type VIII. Review of the literature. Clin Oral Investig 2000;4:66–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rahman N, Dunstan M, Teare MD, et al. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome with severe early-onset periodontal disease (EDS-VIII) is a distinct, heterogeneous disorder with one predisposition gene at chromosome 12p13. Am J Hum Genet 2003;73:198–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Felice C, Toti P, Di Maggio G, et al. Absence of the inferior labial and lingual frenula in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Lancet 2001;357:1500–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shankar S, Shirley E, Burrows NP. Absence of inferior labial or lingual frenula is not a useful clinical marker for Ehlers-Danlos syndrome in the UK. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2006;20:1383–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.