Abstract

Decrypting the structure, function, and molecular interactions of complex molecular machines in their cellular context and at atomic resolution is of prime importance for understanding fundamental physiological processes. Nuclear magnetic resonance is a well-established imaging method that can visualize cellular entities at the micrometer scale and can be used to obtain 3D atomic structures under in vitro conditions. Here, we introduce a solid-state NMR approach that provides atomic level insights into cell-associated molecular components. By combining dedicated protein production and labeling schemes with tailored solid-state NMR pulse methods, we obtained structural information of a recombinant integral membrane protein and the major endogenous molecular components in a bacterial environment. Our approach permits studying entire cellular compartments as well as cell-associated proteins at the same time and at atomic resolution.

Keywords: cellular envelope, Escherichia coli, lipoprotein, PagL, magic angle spinning

Physiological processes rely on the concerted action of molecular entities in and across different cellular compartments. Whereas advancements in molecular imaging have provided unprecedented insights into the macromolecular organization in the subnanometer range (1), studying atomic structure and motion in situ has been challenging for structural biology. NMR has provided insight into cellular processes (2–4) and can determine entire 3D molecular structures inside living cells (5) provided that molecular entities tumble rapidly in a cellular setting. In principle, solid-state NMR (ssNMR) spectroscopy offers a complementary spectroscopic tool to monitor molecular structure and dynamics at atomic resolution in a complex setting (see ref. 6 for a recent review). Indeed, ssNMR has already been used to study individual molecular components in the context of natural bilayers (7, 8), bacterial cell walls (9), and cellular organelles (10).

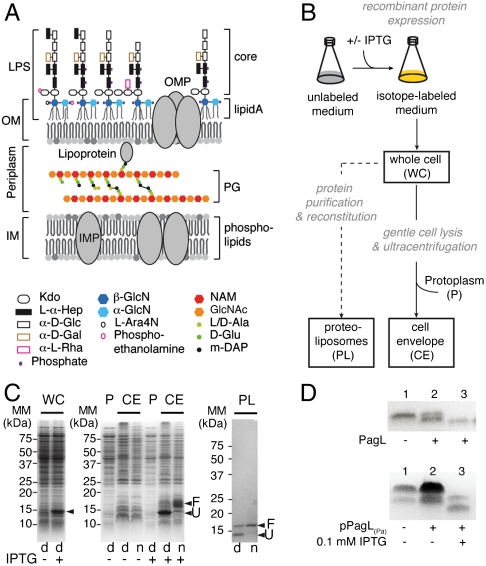

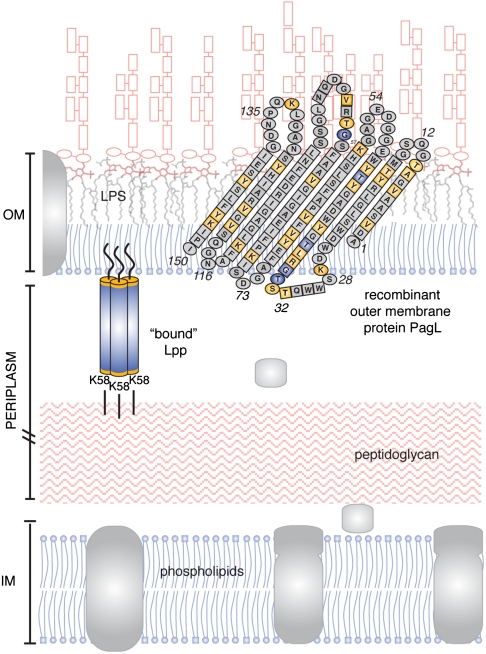

Here, we introduce a general approach to investigate structure and dynamics of an arbitrary molecular target and its potential molecular partners in a cellular setting. Our studies focuses on the Gram-negative bacterial cell that is characterized by a molecularly complex but architecturally unique envelope, consisting of two lipid bilayers, the inner and outer membrane (IM, OM), separated by the periplasm containing the peptidoglycan (PG) layer (Fig. 1A). The IM is a phospholipid bilayer and harbors α-helical proteins, whereas the OM is asymmetrical and consists of phospholipids, lipopolysaccharides (LPS), lipoproteins, and β-barrel-fold integral membrane proteins. LPS forms the outermost layer of the OM and protects the cell against harmful compounds from the environment. PG is a large macromolecule that gives the cell its shape and rigidity.

Fig. 1.

Cellular ssNMR spectroscopy: overall strategy and sample preparation, including inner and outer membrane proteins (IMP, OMP). (A) Schematic structure of the E. coli K-12 cell envelope. (B) Overall scheme for the preparation of WC and CE from strain CE1535 carrying plasmid pPagL(Pa), and of purified PagL protein from strain BL21Star(DE3) carrying plasmid pPagL(Pa)(-) reconstituted in PL. (C) Coomassie-stained SDS/PAGE analysis of WC, CE, and protoplasm (P) fractions obtained from exponentially growing E. coli CE1535 cells containing plasmid pPagL(Pa) and comparison with the reference PL sample. Molecular-mass markers (MM) are indicated next to the gels. Samples were denatured by boiling in SDS (d) or left on ice (n) before electrophoresis. F and U denote the positions of folded and heat-denatured forms of PagL, respectively. (D) In vitro and in vivo LPS deacylase activity of PagL. (Upper) Purified Neisseria meningitidis LPS was incubated in a detergent-containing buffer with (lane 3) or without (lane 1) PagL-containing PL and analyzed by Tricine SDS/PAGE and staining with silver. Membranes from N. meningitidis harboring functional PagL were coanalyzed for reference (lane 2). (Lower) Silver-stained Tricine SDS/PAGE analysis of CE isolated from plasmidless CE1535 cells (lane 1) or noninduced (lane 2) and IPTG-induced (lane 3) CE1535 cells carrying the PagL-encoding plasmid.

Using uniformly 13C,15N-labeled cellular preparations of Escherichia coli, we characterized the structure and dynamics of a recombinant integral membrane protein (PagL) and other major endogenous molecular components of the cell envelope including lipids, the peptidoglycan, and the lipoprotein Lpp (also known as Braun’s lipoprotein). These studies highlight the influence of the surrounding compartment on molecular structure and establish ssNMR under magic angle spinning (MAS) conditions (11) as a high-resolution method to investigate atomic structures of major cell-associated (macro)molecules.

Results

Sample Design for Cellular ssNMR Spectroscopy.

Our goal was to establish general expression and purification procedures that lead to uniformly 13C,15N-labeled preparations of whole cells (WC) and cell envelopes (CE) containing an arbitrary (membrane) protein target (Fig. 1B). As our model system, we selected the 150-residue integral membrane-protein PagL from Pseudomonas aeruginosa, an OM enzyme that removes a fatty acyl chain from LPS (12). We overexpressed pagL under control of the bacteriophage T7 promoter, which is inducible with IPTG, in a mutant E. coli BL21Star(DE3) strain, lacking the two major OM proteins (OMPs) OmpF and OmpA. The suppression of these major OMPs prevented to a large extent the accumulation of the unprocessed signal-peptide-bearing precursor of PagL and led to significant amounts of mature protein in the host membrane when mild recombinant-protein-expression conditions were used (Fig. S1). For optimal analysis of major cell-associated molecular components, E. coli cultures were switched from unlabeled to 15N,13C-isotope labeled growth conditions at the beginning of the exponential growth phase, when recombinant protein production was induced, leading to the incorporation of isotopes in PagL and coexpressed endogenous molecular components. WC and CE samples were prepared from the same exponentially growing culture. As a reference, (U-13C,15N)-labeled PagL was produced in intracellular inclusion bodies, purified, and reconstituted in proteoliposomes (PL, Fig. 1B). Before analysis, WC pellet was washed with PBS, whereas CE and PL were resuspended in Hepes at pH 7.0 and harvested by ultracentrifugation using identical procedures. Both in CE preparations and reconstituted in PL, PagL exhibited similar heat modifiability, a property typical of the well-folded protein (12, 13) (Fig. 1C). To verify that PagL was correctly folded in vivo and in vitro, we monitored its LPS 3-O-deacylase activity in CE and PL preparations as described previously (12, 13). In both cases, LPS was converted into a form with higher electrophoretic mobility (Fig. 1D), in agreement with the expected hydrolysis of the primary acyl chain at position 3 of lipid A. Taken together, our data (heat modifiability and activity assays) indicate that cellular and PL preparations contained well-folded and functional PagL.

NMR Spectra of E. coli Whole Cells and Cell Envelopes Versus Proteoliposomes.

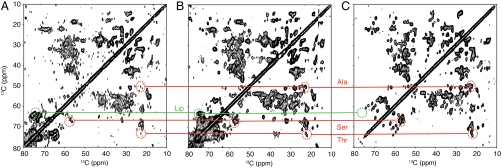

To characterize rigid—presumably membrane-associated—molecular components in WC and CE, we performed a set of 2D 13C-13C correlation experiments employing dipolar-based magnetization transfer steps. Overall, both preparations yielded NMR spectra of astonishing quality considering sample complexity and noncrystallinity (Fig. 2 A and B), with well-dispersed cross-peaks characteristic for protein and lipid signals. As anticipated, we observed an improvement in both sensitivity and spectral resolution for the CE preparation (Fig. S2A), potentially due to the single contribution of CE-associated components. These results were corroborated by SDS/PAGE analysis (Fig. 1C), which showed a significant decrease of the amount of proteins after removal of the protoplasm by cell lysis and ultracentrifugation. Over time, WC and CE preparations did not reveal any marked spectroscopic changes at -2 °C, and the cell morphology and the structural integrity of the CE were preserved after extended NMR studies (Fig. S3). When comparing WC and CE spectra with the reference PL spectrum recorded under similar measurement conditions (Fig. 2C), we found that a large set of intraresidue correlations from PagL, notably cross-peaks of Ala, Thr, and Ser residues in β-sheet protein segments (see below), are well preserved in WC, CE, and PL spectra.

Fig. 2.

NMR spectra of whole cells, cell envelopes, and proteoliposomes. 13C-13C correlation spectra of fully hydrated IPTG-induced WC (A), CE isolated from IPTG-induced WC (B), and (U-13C, 15N)-labeled PagL-containing PL (C) recorded using respectively 224, 336, and 192 scans and processed identically using a sine bell function (SSB of 3.5) and linear prediction in the indirect dimension. Contour plots were adjusted to the same noise level. Characteristic cross-peaks of Ala, Ser, and Thr residues located within PagL β-sheet protein segments and of endogenous E. coli lipids (Lip) are indicated in red and green, respectively.

Conformational Analysis of the PagL Protein in the E. coli Cell Envelope.

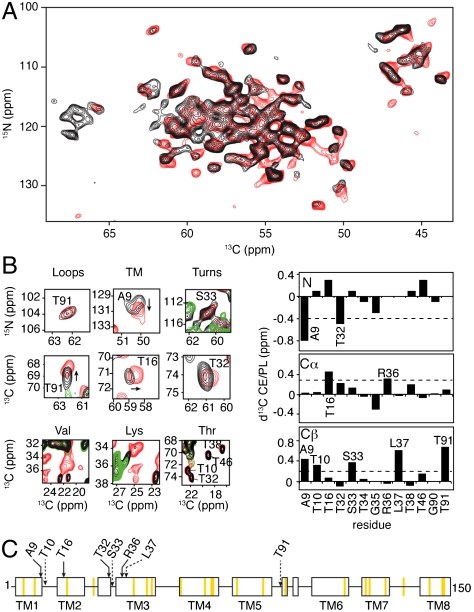

To examine in further detail the conformation of PagL in CE, we performed 2D 15N-13C correlation experiments (14) in which signals arising from nonproteinaceous molecular components are largely reduced. Comparison with the reference PL spectrum (Fig. 3A, red) revealed astonishing similarities. With average 13C and 15N line widths of 0.6–0.8 and 1.5–1.6 ppm, respectively, ssNMR spectra of the CE preparation exhibited comparable, if not superior spectral resolution (Fig. S2B). Because of the favorable spectroscopic dispersion among Thr, Ser, and Gly residues in standard 2D CC/NC correlation experiments, we could subsequently perform a residue-specific analysis, which consisted of three stages. First we determined sequential resonance assignments in PagL-PL preparations in spectroscopically favorable regions. Second, comparison to the same spectral regions in datasets obtained for CE served to obtain tentative assignments for the same PagL residues in the CE case. These were finally cross-validated using additional 2D and 3D datasets. With this strategy, we obtained 15N and 13C resonance assignments for 13 PagL residues located in different topological regions of the protein using CE and PL preparations (Fig. S4 and Table S1). An analysis based on 13C secondary chemical shifts of PagL in CE and in PL was consistent with the presence of Ser33, Thr34, and Thr91 in unstructured protein regions and Ala9, Thr10, Thr16, Thr32, Arg36-Thr38, and Thr46 situated in β-strands (Fig. S5A). These correlations as well as the comparison to the CC correlation pattern predicted on the basis of the X-ray structure suggested that the backbone fold of PagL seen in crystals is largely conserved in the cellular envelope as well as in proteoliposomes (Fig. S5B). In addition to using 15N and 13C chemical shifts, we investigated which protein regions were sensitive to the cellular environment by analyzing cross-peak amplitudes as spectral parameters (Fig. 3B). Detailed ssNMR signal sets extracted from 2D correlation spectra of CE isolated from induced cells (black) or noninduced cells (green) and PL (red) at selected PagL 15N and 13C resonance frequencies are shown in Fig. 3B, Left. The bar diagram (Fig. 3B, Right) displays chemical-shift differences in backbone 15N, and side-chainCβ resonances between CE and PL preparations. Overall, most differences in the backbone chemical shifts were small. Only for Ala9, Thr16, Thr32, and Arg36 we observed 15N or

and side-chainCβ resonances between CE and PL preparations. Overall, most differences in the backbone chemical shifts were small. Only for Ala9, Thr16, Thr32, and Arg36 we observed 15N or  chemical-shift deviations of around 0.6 and 0.4 ppm, respectively (Fig. 3C, arrows). In addition, significant side-chain chemical-shift changes were observed for residues within transmembrane segments (Ala9, Thr10, Leu37), the first periplasmic turn (Ser33), and the third extracellular loop (Thr91). For several assigned correlations, we also observed a sizable attenuation in NMR signal intensity (ranging between 30% and 50%), notably for backbone resonances involving Ala9, Thr91, and Thr32 (Fig. S6A). Even in the absence of residue-specific assignments, we could analyze other amino acid types, including Ser, Ala, Gly, Val, Lys, Tyr, and Trp, based on their characteristic intraresidue correlation pattern and peak positions. Besides subtle backbone chemical-shift changes, we found significant alterations in side-chain resonances of Val, Lys, and Tyr residues, whereas Thr residues are not affected (Fig. 3

B, Left and C, orange bars; see also Fig. S6B). Taken together, these findings suggest an overall conservation of the backbone structure of PagL in the cellular envelope. Larger changes observed for some backbone residues and, in particular, side-chain conformations (Fig. 3C) may reflect structural and/or dynamical alterations that are potentially related to the presence of endogenous membrane-associated molecular components in the CE environment.

chemical-shift deviations of around 0.6 and 0.4 ppm, respectively (Fig. 3C, arrows). In addition, significant side-chain chemical-shift changes were observed for residues within transmembrane segments (Ala9, Thr10, Leu37), the first periplasmic turn (Ser33), and the third extracellular loop (Thr91). For several assigned correlations, we also observed a sizable attenuation in NMR signal intensity (ranging between 30% and 50%), notably for backbone resonances involving Ala9, Thr91, and Thr32 (Fig. S6A). Even in the absence of residue-specific assignments, we could analyze other amino acid types, including Ser, Ala, Gly, Val, Lys, Tyr, and Trp, based on their characteristic intraresidue correlation pattern and peak positions. Besides subtle backbone chemical-shift changes, we found significant alterations in side-chain resonances of Val, Lys, and Tyr residues, whereas Thr residues are not affected (Fig. 3

B, Left and C, orange bars; see also Fig. S6B). Taken together, these findings suggest an overall conservation of the backbone structure of PagL in the cellular envelope. Larger changes observed for some backbone residues and, in particular, side-chain conformations (Fig. 3C) may reflect structural and/or dynamical alterations that are potentially related to the presence of endogenous membrane-associated molecular components in the CE environment.

Fig. 3.

Conformational analysis of PagL. (A) Overlay of 2D NCA correlation spectra of CE isolated from IPTG-induced WC (black) and PL (red), recorded with identical acquisition and processing parameters—i.e., with a sine bell function (SSB = 4.5) and using linear prediction in indirect dimension. (B) Comparison of PagL in CE and PL environments. (Left) Selected spectral regions from 2D homonuclear and heteronuclear spectra of CE isolated from IPTG-induced WC (black) showing isolated PagL resonances, and overlaid with spectra obtained on CE isolated from noninduced WC (green) and PL (red). Assignments are indicated where available. (Right) Backbone N, Cα, and Cβ chemical-shift changes observed for PagL embedded in E. coli CE and in PL. Horizontal lines indicate the threshold for significant chemical-shift changes. The threshold was set to 2 times  . Residues with a chemical-shift deviation larger than the threshold (+ 2 SD) are labeled. (C) Summary of PagL ssNMR spectral changes between CE and PL preparations plotted onto the topological representation of PagL according to the crystal structure (β-sheet protein segments are represented by open rectangles and transmembrane segments TM1–8 are labeled). Arrows point to residues that experienced significant backbone (solid lines) and side-chain (dashed lines) chemical-shift changes, whereas orange filled bars indicate major alterations in signal intensities (> 50%) between CE and PL.

. Residues with a chemical-shift deviation larger than the threshold (+ 2 SD) are labeled. (C) Summary of PagL ssNMR spectral changes between CE and PL preparations plotted onto the topological representation of PagL according to the crystal structure (β-sheet protein segments are represented by open rectangles and transmembrane segments TM1–8 are labeled). Arrows point to residues that experienced significant backbone (solid lines) and side-chain (dashed lines) chemical-shift changes, whereas orange filled bars indicate major alterations in signal intensities (> 50%) between CE and PL.

Characterization of the Endogenous E. coli Lipoprotein Lpp.

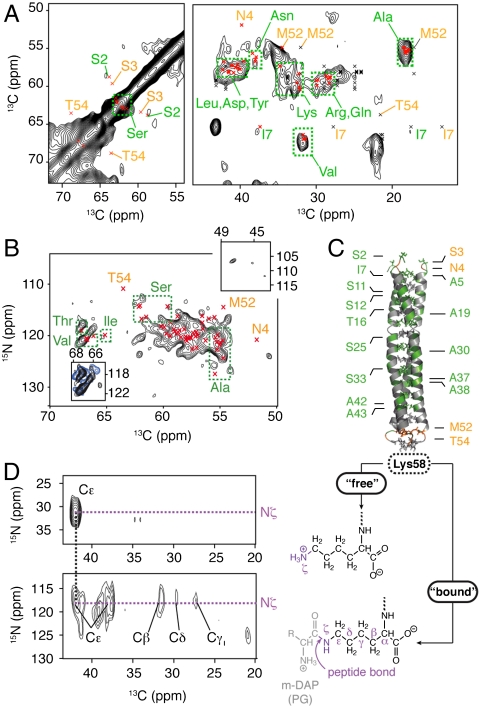

With up to about 7.2 × 105 copies per cell, the lipoprotein Lpp, or Braun’s lipoprotein (15), belongs to the most abundant CE proteins in exponentially growing E. coli cells. Lpp is found in both “free” and “bound” forms, the latter being covalently attached to the PG network (16, 17). In solution, the 56-residue polypeptide moiety, called Lpp-56, associates to form a hydrophilic homotrimer composed of a three-stranded coiled-coil domain and two helix-capping motifs (18), but a model for a lipophilic superhelical assembly containing six subunits has also been proposed (16). We first monitored the presence of free Lpp by SDS/PAGE analysis of CE preparations followed by immunoblotting (Fig. S7A). We next performed a series of 2D 15N-13C and 13C-13C correlation experiments on CE isolated from noninduced WC and compared results with predictions based on the available high-resolution 3D structure of Lpp-56. We found good agreement between our data and predicted intraresidue backbone C–C (Fig. 4A) as well as N–Cα (Fig. 4B) correlation patterns, suggesting the predominance of well-folded Lpp in the CE preparations. These results were further supported by weak signal intensities in spectral regions characteristic for glycine (Fig. 4B, Upper Right Inset), which is missing in the amino acid composition of Lpp. In addition, isolated backbone and side-chain resonances corresponding to Ala, Val, and Ile residues were readily observed around peak positions predicted from the crystal structure (18) (Fig. 4

A and B, red crosses). In the X-ray structure, these residues pack against each other to form the hydrophobic interface between the three helices (Fig. 4C, green). Interestingly, both peak positions and spectral resolution are well preserved in the presence of recombinant protein PagL in the OM (Fig. 4B, Lower Left Inset, blue spectrum). In contrast, we observed a systematic deviation between our data and predicted (Fig. 4

A and B, orange) 13C and 15N resonances for N- and C-terminal residues (Ser3, Asn4, Met52, Thr54), which exceeded the standard deviation. We thus speculate that potential conformational and/or dynamical changes occur between crystalline Lpp and native Lpp around these residues. In vivo, Lpp has characteristic covalent modifications at its N and C termini (19). About one-third of Lpp molecules is covalently bound to the PG layer. Such a modification involves the formation of a peptide bond between the free ϵ-amino group of the C-terminal Lys of Lpp and the free carboxylate group of meso-diaminopimelic acid residues in PG (Fig. 4C). We thus recorded a 2D (15N-  ) correlation spectrum using a larger spectral window that includes the side-chain region (Fig. 4D). We identified two intense cross-peaks in the amide region at the expected Cϵ carbon frequency of free Lys. These signals were correlated to a set of additional signals at 32, 27, and 29.5 ppm, in good agreement with averaged 13C chemical shifts of Lys Cβ, Cγ, and Cδ side-chain resonances and strongly suggesting that a bound Lpp contribution is detected in the CE spectrum.

) correlation spectrum using a larger spectral window that includes the side-chain region (Fig. 4D). We identified two intense cross-peaks in the amide region at the expected Cϵ carbon frequency of free Lys. These signals were correlated to a set of additional signals at 32, 27, and 29.5 ppm, in good agreement with averaged 13C chemical shifts of Lys Cβ, Cγ, and Cδ side-chain resonances and strongly suggesting that a bound Lpp contribution is detected in the CE spectrum.

Fig. 4.

Identification and characterization of the lipoprotein Lpp. (A) Two-dimensional (13C-13C) and (B) 2D NCA correlation spectra obtained on the CE isolated from noninduced WCs overlaid with backbone Cα-Cβ and N-Cα (red crosses) intraresidue correlations predicted from the crystal structure of Lpp (Protein Data Bank ID code 1EQ7) using SPARTA+ (33). For other carbon positions (black crosses), average 13C chemical-shift values given in the Biological Magnetic Resonance Data Bank (http://www.bmrb.wisc.edu/ref_info/statsel.htm) were used. Characteristic correlations are labeled and color coded: orange for correlations absent in the experimental data and green for correlations that are in agreement with chemical-shift predictions. (Inset, Upper Right) Spectral region characteristic of Gly residues. (Inset, Lower Left) An overlay of 2D NCA spectra for α-helical Thr, Val, and Ile N-Cα correlations in CE isolated from non- (black) and IPTG-induced (blue) cells. (C) Summary of the structural analysis of Lpp based on ssNMR spectra obtained on CE isolated from noninduced cells. Residues for which backbone correlations significantly deviate or not from predictions are labeled and highlighted in orange or green, respectively. (D) Two-dimensional NCA correlation spectrum including side-chain amide 15Nζ resonances of Lys revealing distinct and characteristic NC correlation patterns for the free (Upper) and the bound (Lower) forms of Lpp. Meso-diaminopimelic acid, m-DAP.

Resonance Assignment of Mobile LPS and PG.

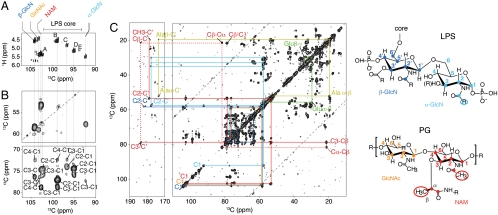

We could readily characterize highly flexible PG, located in the periplasm, and LPS in the OM in 2D (1H,13C) as well as (13C-13C) through-bond correlation spectra obtained on CE preparations. LPS consists of a 1,4′-bisphosphorylated β-1,6-linked glucosamine disaccharide (α- and β-GlcN), substituted with fatty acid chains at positions 2, 3, 2′, and 3′ and with an oligosaccharide core at position 6′. PG is a giant heteropolymer made of linear glycan strands of alternating β-1,4-linked N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) and N-acetylmuramic acid (NAM) residues, which are cross-linked by short peptides. First, we recorded a 2D (1H-13C) insensitive nuclei enhanced by polarization transfer (INEPT) spectrum to examine the sugar heterogeneity/composition in our sample. Intense and very well-resolved cross-peaks were found at peak positions corresponding to anomeric H1/C1 atoms from carbohydrate units (Fig. 5A). The 13C dispersion between 90 and 104 ppm was consistent with the presence of nine carbohydrate species, in α- and β-configuration. Glucosamine units, constituting exclusively the PG backbone (GlcNAc and NAM) and the lipid A moiety of the LPS (β-d-GlcN and α-d-GlcN) can be distinguished from sugars of the LPS core (labeled A–E) based on a characteristic one-bond CC connectivity between anomeric carbon and nitrogen-substituted C2 in a 2D (13C,13C) correlation spectrum (Fig. 5B). Next, we identified carbohydrate units by tracing CC and HC connectivities within the sugar rings and their substituents (20, 21) (Fig. 5C and Fig. S7B). Using this strategy, we obtained de novo ssNMR assignments of LPS and PG glucosamine units and some of their substituents (Table S1). Solid-state NMR chemical shifts were compatible with the presence of polysubstituted glucosamine units within the lipid A of LPS and backbone PG moieties, as previously deduced from the analysis of purified molecules (21–23), even when part of cell envelope preparations. However, carbohydrates from the core of the LPS could not be identified unambiguously due to the large overlap of 13C and 1H resonances and the inherent structural heterogeneity of the LPS core region (Fig. S7C).

Fig. 5.

Resonance assignment of flexible LPS and PG using through-bond ssNMR correlation spectroscopy. (A) Expansion of the 2D (1H-13C) insensitive nuclei enhanced by polarization transfer (INEPT) correlation spectrum obtained on CE isolated from IPTG-induced WC, showing dispersion and resolution of individual α- and β-anomeric resonances of LPS and PG sugar moieties. Splitting due to the C1-C2 scalar coupling is visible for all anomeric resonances and varied between 47 and 53 Hz. Color coding: β-GlcN, dark blue; α-GlcN, light blue; PG GlcNAc, orange; NAM, red; LPS core, black. (B) Sections from the 2D (13C-13C) INEPT-total through-bond correlation spectroscopy showing characteristic correlations between anomeric C1 and one-bond nitrogen-substituted C2 carbons (Upper) or one-to-three bonded non nitrogen-substituted C2-C4 carbons (Lower) of LPS and PG sugar moieties. The CC and HC correlations that belong to the same spin system are connected by dashed lines. (C) Residue-specific ssNMR assignment of LPS and PG glucosamine units based on 13C-13C connectivities within the sugar rings and their substituents (see also Fig. S7A). Assigned resonances from LPS and PG glucosamine units are highlighted by filled circles onto chemical structures with the same color coding as in A.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that cellular ssNMR spectroscopy can be used to probe atomic details of integral membrane proteins and endogenous membrane-associated molecular components in a bacterial cellular setting. We showed that 15N-edited datasets as well as the combined use of through-space and through-bond ssNMR experiments reduces spectral complexity and facilitates the discrimination between proteinaceous and nonproteinaceous molecular components at different levels of molecular mobility.

By analyzing (U-13C,15N)-labeled E. coli cell envelopes, we found that LPS and PG moieties can exhibit a remarkable degree of molecular motion (Fig. 6, red), while the protein components investigated were well folded in the cellular membrane context (Fig. 6, blue). In the case of Lpp, our results strongly support the anchoring of the protein to the underlying PG layer by virtue of the side chain of the C-terminal lysine. Although our data are consistent with the overall 3D model for the isolated Lpp protein moiety, substantial conformational changes are predicted for residues located at the N- and C-terminal extremities of the protein, which are covalently substituted in vivo. Further cellular ssNMR studies may reveal the conformation of the free form of Lpp that has been postulated to cross the OM (17). In the case of PagL, for which high-resolution ssNMR spectra were obtained for all studied preparations, we demonstrated that the global fold of the protein as seen in the crystal structure was largely preserved in both PL and CE environments, including the presence of β-sheet structure in the first periplasmic turn, which involved Thr32. On the other hand, several protein backbone resonances related to residues located in the first periplasmic turn, the transmembrane segments 1–3, and in the third extracellular loop were sensitive to the molecular environment. Alterations in ssNMR signal intensity were detected predominantly for aromatic, hydrophobic, and charged residues. Interestingly, these PagL residues are located in protein segments potentially exposed to other major membrane-associated cellular components, including LPS and the PG (Fig. 6, orange). Similar to the case of Lpp, further ssNMR studies will help to establish the structural details of the molecular interaction of PagL and its substrate LPS, to dissect active and latent PagL conformations that depend on its molecular environment (24), and to establish the physiological relevance of PagL dimers (13) in a native-like environment.

Fig. 6.

Atomic-level insights of E. coli CE-associated macromolecules revealed by cellular ssNMR spectroscopy. Schematic representation of the CE from E. coli showing rigid (blue) and flexible (red) (non)proteinaceous molecular components characterized by through-bond and through-space ssNMR experiments, respectively. The topological representations of PagL and Lpp as seen in the available 3D models of isolated molecules are indicated. For PagL, residues located in β-strand and random-coil protein segments are represented by squares and circles, respectively. Residues that were not included in the analysis are colored in gray. Amino acids are given in single-letter notation. Spectroscopic changes of large (chemical-shift deviation > 0.4 ppm and/or signal intensity variations > 50%) and small magnitude that are potentially related to association between membrane protein and OM (or PG) are indicated for both proteins in orange and blue, respectively.

With increasing levels of molecular complexity, spectroscopic sensitivity becomes a critical factor. Nevertheless, one- and two-dimensional ssNMR spectroscopy of whole cell preparations such as shown in this study is possible (Fig. 2A). In addition, WC preparations can be readily combined with state-of-the-art ssNMR signal enhancement methods operating at low temperature, thereby reducing acquisition times significantly (25). Such technologies are likely to reduce the expression levels needed to perform cellular ssNMR experiments. In the present study, the expression levels of PagL were comparable to those of the endogenous protein Lpp (Fig. S2B). Dedicated preparation methods (see, e.g., ref. 6) including the single-protein production method (26) are available to further reduce unwanted background contributions. Cellular ssNMR spectroscopy as described herein opens opportunities for the structural investigation of large and/or membrane-associated macromolecules. Already, the cell envelope of Gram-negative bacteria, including the IM, the periplasm, and the OM, epitomizes a model organelle involved in a large number of functions critical for cellular physiology. With recent advances in using insect and mammalian cells for producing recombinant eukaryotic proteins, cellular ssNMR as shown here could also be applicable to recombinant eukaryotic proteins in specific compartments—i.e., after isolation of the cellular membrane or intracellular organelles. Using cellular ssNMR, the structural investigation of fundamental processes, such as ligand/drug binding or membrane-protein folding mediated by complex proteinaceous machineries, should be possible, thereby bridging the gap between structural and cellular biology.

Materials and Methods

Expression Vectors and Bacterial Strains.

The pET11a-derived plasmids pPagL(Pa) and pPagL(Pa)(-) encoding P. aeruginosa PagL with and without signal sequence, respectively, have been described (12). Mutant derivatives of E. coli BL21Star(DE3) lacking the OmpF and/or OmpA proteins were isolated by selection for resistance to the OmpF- and OmpA-specific bacteriophages TuIa (27) and K3 (28), respectively. Mutants lacking OmpF, OmpA, or both were designated CE1536, CE1537, and CE1535, respectively.

Sample Preparation.

WC and CE NMR samples were prepared from 50 and 200 mL of the cultures, respectively, following the procedure described in SI Materials and Methods. For CE NMR samples, cells were disrupted in presence of EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich) using a precooled French pressure cell (8,000 psi). Unbroken cells were removed by multiple centrifugation steps (1,000 × g, 10 min, 4 °C) until a pellet was no longer detectable. The CE fraction was isolated by ultracentrifugation of the cell lysate for 8 min at 150,000 × g and at 4 °C. The correct localization and membrane insertion of PagL was confirmed on Coomassie-stained SDS/PAGE gels after extracting the CE with 1% N-lauroylsarcosine or 6 M urea as described previously (29, 30). To obtain the reference PL ssNMR spectra, PagL was expressed as intracellular inclusion bodies in E. coli BL21Star(DE3) harboring the plasmid pPagL(Pa)(-), then purified, and reconstituted in dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine vesicles at a final protein-to-lipid molar ratio of 1∶50 as described in SI Materials and Methods. Before packing, the CE and PL pellets were resuspended in 500 μL of 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.0) and harvested by ultracentrifugation (90,000 × g for 45 min at 4 °C). Freshly prepared and fully hydrated WC, CE, and PL samples were transferred into 3.2-mm MAS rotors by low-speed centrifugation, packed with bottom and top spacers, and subsequently analyzed by ssNMR spectroscopy. In the PagL-PL case, we estimate 8 mg of protein present in the NMR rotor.

NMR Spectroscopy.

The ssNMR analysis of cellular and proteoliposome preparations was based on a set of multidimensional homonuclear and heteronuclear ssNMR experiments employing dipolar- or scalar-based magnetization transfer steps as detailed in SI Materials and Methods. Solid-state NMR experiments were performed at a regulated sample temperature of -2 °C on a narrow-bore Bruker Avance 700 spectrometer equipped with a 3.2-mm triple-resonance (1H,13C,15N) Efree MAS probe. 13C and 1H resonances were calibrated using adamantane as an external reference. The upfield 13C resonance and isotropic 1H resonance of adamantane were set to 31.47 and 1.7 ppm, respectively, to allow for a direct comparison of the solid-state chemical shifts to solution-state NMR data. Accordingly, 15N resonances were calibrated using the tripeptide AGG (31) as an external reference. A summary of acquisition and process parameters is given in Table S2. NMR spectra were processed using Topspin 3.0 (Bruker Biospin) and analyzed with Sparky (32).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

Technical assistance by Deepak Nand, Christian Ader, and Hans Meeldijk is gratefully acknowledged. This work was supported by Nederlandse organisatie voor wetenschappelijk onderzoek (700.26.121, 700.10.433, and 815.02.012) and received funding from the European Community’s Seventh Framework Program (FP7/2007-2013) under Grant Agreement 211800.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. R.T. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

See Commentary on page 4715.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1116478109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Leis A, Rockel B, Andrees L, Baumeister W. Visualizing cells at the nanoscale. Trends Biochem Sci. 2009;34:60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matwiyoff NA, Needham TE. Carbon-13 NMR spectroscopy of red blood cell suspensions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1972;49:1158–1164. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(72)90590-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selenko P, et al. In situ observation of protein phosphorylation by high-resolution NMR spectroscopy. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:321–329. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Serber Z, et al. High-resolution macromolecular NMR spectroscopy inside living cells. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:2446–2447. doi: 10.1021/ja0057528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakakibara D, et al. Protein structure determination in living cells by in-cell NMR spectroscopy. Nature. 2009;458:102–105. doi: 10.1038/nature07814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Renault M, Cukkemane A, Baldus M. Solid-state NMR spectroscopy on complex biomolecules. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2010;49:8346–8357. doi: 10.1002/anie.201002823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harbison GS, et al. Dark-adapted bacteriorhodopsin contains 13-cis, 15-syn and all-trans, 15-anti retinal Schiff bases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:1706–1709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.6.1706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fu R, et al. In situ structural characterization of a recombinant protein in native Escherichia coli membranes with solid-state magic-angle-spinning NMR. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:12370–12373. doi: 10.1021/ja204062v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacob GS, Schaefer J, Wilson GE. Direct measurement of peptidoglycan cross-linking in bacteria by 15N nuclear magnetic resonance. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:10824–10826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sivertsen AC, Bayro MJ, Belenky M, Griffin RG, Herzfeld J. Solid-State NMR evidence for inequivalent GvpA subunits in gas vesicles. J Mol Biol. 2009;387:1032–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andrew ER, Bradbury A, Eades RG. Nuclear magnetic resonance spectra from a crystal rotated at high speed. Nature. 1958;182:1659. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geurtsen J, Steeghs L, ten Hove J, van der Ley P, Tommassen J. Dissemination of lipid A deacylases (PagL) among Gram-negative bacteria: Identification of active-site histidine and serine residues. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:8248–8259. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414235200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rutten L, et al. Crystal structure and catalytic mechanism of the LPS 3-O-deacylase PagL from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:7071–7076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509392103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baldus M. Correlation experiments for assignment and structure elucidation of immobilized polypeptides under magic angle spinning. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. 2002;41:1–47. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braun V, Bosch V. In vivo biosynthesis of murein-lipoprotein of the outer membrane of E. coli. FEBS Lett. 1973;34:302–306. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(73)80817-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inouye M. A three-dimensional molecular assembly model of a lipoprotein from the Escherichia coli outer membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:2396–2400. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.6.2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cowles CE, Li Y, Semmelhack MF, Cristea IM, Silhavy TJ. The free and bound forms of Lpp occupy distinct subcellular locations in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2011;79:1168–1181. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07539.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shu W, Liu J, Ji H, Lu M. Core structure of the outer membrane lipoprotein from Escherichia coli at 1.9 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 2000;299:1101–1112. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braun V. Covalent lipoprotein from the outer membrane of Escherichia coli. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1975;415:335–377. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(75)90013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raetz CR, Reynolds CM, Trent MS, Bishop RE. Lipid A modification systems in gram-negative bacteria. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:295–329. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.010307.145803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kern T, et al. Toward the characterization of peptidoglycan structure and protein-peptidoglycan interactions by solid-state NMR spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:5618–5619. doi: 10.1021/ja7108135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mares J, Kumaran S, Gobbo M, Zerbe O. Interactions of lipopolysaccharide and polymyxin studied by NMR spectroscopy. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:11498–11506. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806587200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muller-Loennies S, Lindner B, Brade H. Structural analysis of oligosaccharides from lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of Escherichia coli K12 strain W3100 reveals a link between inner and outer core LPS biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:34090–34101. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303985200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawasaki K, China K, Nishijima M. Release of the lipopolysaccharide deacylase PagL from latency compensates for a lack of lipopolysaccharide aminoarabinose modification-dependent resistance to the antimicrobial peptide polymyxin B in Salmonella enterica. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:4911–4919. doi: 10.1128/JB.00451-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Renault M, et al. Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy on Cellular Preparations Enhanced by Dynamic Nuclear Polarizatio. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012 doi: 10.1002/anie.201105984. 10.1002/anie.201105984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suzuki M, Mao L, Inouye M. Single protein production (SPP) system in Escherichia coli. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:1802–1810. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Datta DB, Arden B, Henning U. Major proteins of the Escherichia coli outer cell envelope membrane as bacteriophage receptors. J Bacteriol. 1977;131:821–829. doi: 10.1128/jb.131.3.821-829.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skurray RA, Hancock RE, Reeves P. Con–mutants: Class of mutants in Escherichia coli K-12 lacking a major cell wall protein and defective in conjugation and adsorption of a bacteriophage. J Bacteriol. 1974;119:726–735. doi: 10.1128/jb.119.3.726-735.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Voulhoux R, Bos MP, Geurtsen J, Mols M, Tommassen J. Role of a highly conserved bacterial protein in outer membrane protein assembly. Science. 2003;299:262–265. doi: 10.1126/science.1078973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hobb RI, Fields JA, Burns CM, Thompson SA. Evaluation of procedures for outer membrane isolation from Campylobacter jejuni. Microbiology. 2009;155:979–988. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.024539-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luca S, et al. Secondary chemical shifts in immobilized peptides and proteins: A qualitative basis for structure refinement under magic angle spinning. J Biomol NMR. 2001;20:325–331. doi: 10.1023/a:1011278317489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goddard TD, Kneller DG. San Francisco: University of California; SPARKY 3. http://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/home/sparky. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shen Y, Bax A. SPARTA+: A modest improvement in empirical NMR chemical shift prediction by means of an artificial neural network. J Biomol NMR. 2010;48:13–22. doi: 10.1007/s10858-010-9433-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.