Abstract

Titanium(IV) compounds are excellent anticancer drug candidates, but they have yet to find success in clinical applications. A major limitation in developing further compounds has been a general lack of understanding of the mechanism governing their bioactivity. To determine factors necessary for bioactivity, we tested the cytotoxicity of different ligand compounds in conjunction with speciation studies and mass spectrometry bioavailability measurements. These studies demonstrated that the Ti(IV) compound of N,N′-di(o-hydroxybenzyl)ethylenediamine-N,N′-diacetic acid (HBED) is cytotoxic to A549 lung cancer cells, unlike those of citrate and naphthalene-2,3-diolate. Although serum proteins are implicated in the activity of Ti(IV) compounds, we found that these interactions do not play a role in [TiO(HBED)]− activity. Subsequent compound characterization revealed ligand properties necessary for activity. These findings establish the importance of the ligand in the bioactivity of Ti(IV) compounds, provides insights for developing next-generation Ti(IV) anticancer compounds, and reveal [TiO(HBED)]− as a unique candidate anticancer compound.

Keywords: drug delivery, transferrin, albumin, metal-based anticancer compounds

Titanium(IV) compounds are promising candidates in the search for highly potent anticancer agents with a wide spectrum of activity. Interest in these compounds dates back to the 1970s soon after the serendipitous and revolutionary discovery of cisplatin (1), a platinum-based anticancer drug. Today platinum-based compounds are one of the major anticancer drugs on the market, but there exists a high demand for alternatives with fewer side effects and broader efficacy. More importantly, some cancers rapidly acquire resistance to cisplatin (2), and compounds that can avoid this resistance will be of use clinically. Searches for other metal-based anticancer compounds led to the discovery of titanium compounds.

The two most promising titanium-based compounds, budotitane and titanocene dichloride, exhibited a greater spectrum of activity and fewer side effects than cisplatin (3). However, they stalled in clinical trials because of complicated formulation issues and/or ineffectiveness arising from the solution instability of the compounds caused by the hydrolytic propensity of Ti(IV) (3). The hydrolysis of Ti(IV) results in the irreversible formation of insoluble TiO2 and the loss of anticancer activity. Progress has been made in the synthesis of derivatives of budotitane and titanocene dichloride (4), and cytotoxicity assays have been used to gauge the potential anticancer properties of these compounds, which can be insufficient (5). The aqueous properties of these newer Ti(IV) compounds are not typically considered during these studies, which results in compounds that suffer from the same problems as the parent compounds. Specifically, they tend to be highly water-insoluble and/or readily labile at physiological conditions. The seemingly paradoxical nature of these compounds to exhibit their effect in cancer cells has been an important area of research.

To explain how insoluble and/or highly labile Ti(IV) compounds are cytotoxic, the serum protein transferrin (Tf) has been implicated in the complexation and delivery of these compounds. The favored hypothesis is that the compounds deliver Ti(IV) to Tf, which then transports the metal ion to cancer cells via the Fe(III) endocytotic route (Fig. S1) (6). Evidence in support of this hypothesis is that Tf (which possesses two identical metal-binding sites) is only 39% Fe(III)-saturated (7) and can thus bind and transport other metal ions, typically hard metal ions (8). Ti(IV) has been shown to bind with very high affinity to Tf (9, 10), even higher than Fe(III) (9). In vivo studies have shown Ti(IV) to be endogenously bound to Tf (11). Furthermore, Ti(IV) from titanocene dichloride rapidly binds to Tf (6). Moreover, Ti(IV)-bound Tf (Ti2-Tf) is thought to specifically target cancer cells because some cancer cells express higher levels of Tf receptors (12). Ti2-Tf binds with high affinity to Tf receptor 1 (TfR1) (13), and it has also been shown to block Fe(III)-bound Tf (Fe2Tf) from entering a placental cancer cell line (6). In this model, the Ti(IV) compounds play a prodrug role. Minimizing the lability of Ti(IV) compounds is thought to better facilitate delivery of Ti(IV) to Tf (14).

Several studies, however, demonstrate that Tf may not significantly contribute to the ability of Ti(IV) to induce cell death. In one study, structurally similar titanocenes that deliver Ti(IV) to Tf at comparably fast rates and degrees of saturation were found not only to poorly induce cytotoxicity in HT-29 colon cancer cells but also to induce at different half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50) (15). In more conclusive studies, the addition of Tf to cell-viability assays did not improve the cytotoxicity of different Ti(IV) compounds in several cell lines, with the exception of titanocene dichloride in some instances (16–19).

Serum albumin (SA), the most abundant serum protein, was recently proposed to participate in the anticancer property of Ti(IV) compounds by facilitating the transport of these compounds into cancer cells (Fig. S1) (13, 20). SA's impressive ability to bind and transport different classes of ligands at multiple binding sites is currently being exploited in the design of drugs that specifically target SA or are conjugated to the protein (21). SA has been shown to bind hard metals such as Ti(IV) in metal-chelate form (13, 20). Binding to SA affords a mechanism by which a Ti(IV) compound, such as the titanocene moiety (22, 23), could be delivered intact to cancer cells and directly exhibit its effect. Several hydrolysis-prone Ti(IV) compounds, including the titanocene moiety, importantly, bind to SA (13, 20, 22, 23). However, similar to results with Tf, the addition of SA to cell-viability assays does not improve the cytotoxicity displayed by different Ti(IV) compounds (24), except Titanocene Y (24). Clearly, other factors are involved in the transport of, and activity exhibited by, cytotoxic Ti(IV) compounds.

Although the role of transfer proteins is not conclusive, studies suggest that the structure of Ti(IV) compounds is likely playing an important role. For many Ti(IV) compounds, the identity of their ligands is far more important to their cytotoxicity than was originally appreciated. Recently, greater emphasis has been placed on using less labile ligands in the synthesis of Ti(IV) compounds. The substitution of fluoride for chloride in several titanocene-related compounds, for instance, has dramatically improved their ability to induce cell death in HeLa S3 and Hep G2 cells (25). The ligands also play more important roles than simply that of a hydrolysis preventative medium. The anticancer behavior of Ti(IV) compounds is likely attributable to specific features of the ligands. One study suggests that partial ligand dissociation of titanocene-related compounds may result in ligand coordination rearrangement (26). This rearrangement would change the overall charge of the compound from neutral to positive and may facilitate direct interaction with the DNA backbone through ionic interactions resulting in cell death (26). Another study shows that substitutions ortho to the binding phenolato unit of salan-type ligands influences the cytotoxicity of these types of Ti(IV) compounds because of electronic and steric effects (27). In addition, both the chirality of ligands (28) and ligand coordination to Ti(IV) (28, 29) can affect the cytotoxicity of Ti(IV) compounds.

The ligand properties that are essential for the cytotoxicity of Ti(IV) compounds are not well defined and appear to be cell-specific. A549 human lung cancer cells, which are susceptible to cisplatin, have previously been studied in Ti(IV) research, with specific focus on titanocene compounds. The parent compound titanocene dichloride does not kill A549 cells well (IC50 > 100 μM); however, modifications of the cyclopentadienyl ring can improve the ability of titanocenes to induce A549 cell death (30–32). The improvement in water solubility is the most probable rationale as to why certain modifications improve the potency of the compound. These studies strongly support the need to investigate ligand properties essential for Ti(IV) cytotoxicity.

Herein, we examine the ability of three Ti(IV) compounds to induce cell death in A549 cells. We attain insight into the ligand properties imperative to A549 cell death through the selection of the ligands: citrate, naphthalene-2,3-diolate (Fig. S2), and N,N′-di(o-hydroxybenzyl)ethylenediamine-N,N′-diacetic acid (HBED) (Fig. 1). These ligands greatly differ in their Ti(IV) binding lability, polarity, and bioactivity. The [TiO(HBED)]− compound is found to be the only cytotoxic agent with potent activity comparable to cisplatin. Aqueous speciation, MS, and serum protein-interaction studies demonstrate that [TiO(HBED)]− exhibits its effect via a serum protein-independent but ligand-dependent pathway. This paper reveals the importance of the ligand in the activity of Ti(IV) compounds and demonstrates a specific approach toward the development of Ti(IV)-based anticancer therapeutics.

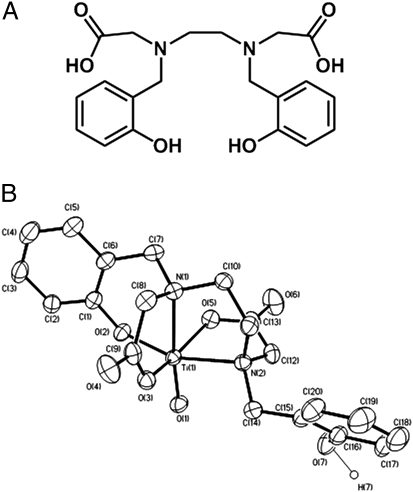

Fig. 1.

Ti(IV) chelation by HBED. (A) HBED structure. (B) ORTEP diagram of [TiO(HBED)]−.

Results

Crystal Structure of (C6H5)4P[TiO(C20H21N2O6)]⋅Dimethylformamide (1DMF).

[TiO(HBED)]− was crystallized at pH 7.0 (Fig. 1) in the presence of (C6H5)4P+ and DMF. The complex differs in the denticity of HBED chelation from Ti(HBED) formed at pH 3.0 (33). The increase in pH results in dissociation of one of the phenolate oxygens from Ti(IV), transforming HBED from a hexadentate to a pentadentate ligand. In place of the phenolate oxygen, which becomes protonated, is a terminal oxo ligand. The pH 7.0 compound has spectroscopic features (SI Materials and Methods) that are characteristic of other titanyl complexes (34–38). Relevant crystallographic data are presented in Tables S1 and S2.

Spectropotentiometric Titration of Ti(IV) HBED.

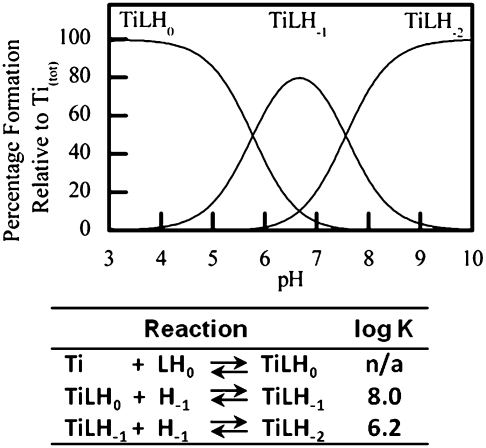

The spectropotentiometric titration study of Ti(IV) HBED at micromolar concentrations revealed HBED binding Ti(IV) with high affinity throughout the pH range 3–10 (Fig. 2) in monomeric form. HBED transforms from a hexadentate, fully deprotonated ligand in the acidic region to pentadentate in the neutral region, which remains deprotonated or gains a proton, as in the pH 7.0 crystal structure, because either hydroxide or oxide binds to Ti(IV) (Figs. S3 and S4). The neutrally charged Ti(HBED) dominates in the acidic region, whereas two negatively charged hydrolyzed species dominate in the neutral and basic regions. For the following studies performed at pH 7.4, [TiO(HBED)]− and HBED− are the dominant species.

Fig. 2.

pH speciation diagram for Ti(IV) coordination by HBED in a 1:1 molar ratio at micromolar concentration in 0.1 M KCl (aqueous) and the corresponding relative binding constants (log K). Negative protonation states (H−1 and H−2) refer to hydrolysis resulting in hydroxo or oxo ions binding to Ti(IV).

Reactivity of [TiO(HBED)]− with Tf and SA.

Equilibrium dialysis performed at pH 7.4 revealed that [TiO(HBED)]− does not deliver Ti(IV) to Tf nor does it bind to SA at micromolar concentrations. The absence of Ti(IV) content was confirmed by a Ti(IV)-based colorimetric assay and UV-visible spectra of the dialyzed protein solutions, revealing apoproteins.

Cytotoxicity Experiments.

The results of all cytotoxicity experiments performed on A549 cells are listed in Table 1. Although Ti(IV) citrate (with and without excess citrate) and Ti(naphthalene-2,3-diolate)32− were inactive against the cells, [TiO(HBED)]− exhibited a dose-dependent antiproliferative effect (IC50 = 24.6 ± 0.8 μM; Fig. S5) that was nearly a factor of four more efficacious than that of HBED− alone. The presence of physiological concentrations of Tf and SA did not improve the cytotoxicity of [TiO(HBED)]−; in fact, [TiO(HBED)]− exhibited slightly weaker potency (Fig. S6). Ti(IV) bound to Tf in both unhydrolyzed and hydrolyzed forms, and as a titanocene compound bound to SA, did not demonstrate any cytotoxic property. The Ti(IV) small compounds were inactive against HL-60 leukemia and UACC-62 melanoma cells.

Table 1.

Effects of Ti(IV) complexes, ligands, and serum proteins Tf and SA on A549 tumor cell viability (IC50, μM)

| Agent | Tf* | SA* | IC50, μM |

| [TiO(HBED)]− | − | − | 24.6 ± 0.8 |

| + | − | 42.7 ± 6.8 | |

| − | + | 32.7 ± 9.9 | |

| HBED− | − | − | 96.1 ± 15 |

| Ti citrate† | − | − | >100 |

| Ti citrate + 100 μM citrate3− | − | − | >100 |

| Citrate3− | − | − | >100 |

| Ti(naphthalene-2,3-diolate)32− | − | − | >100 |

| Naphthalene-2,3-diolate1− | − | − | >100 |

| Titanocene dichloride | − | − | >100 |

| + | − | >100 | |

| − | + | >100 | |

| Ti2-Tf unhydrolyzed | N/A | N/A | >100 |

| Ti2-Tf hydrolyzed | N/A | N/A | >100 |

| Tf | N/A | N/A | >100 |

| Ti-SA | N/A | N/A | >100 |

| SA | N/A | N/A | >100 |

| Cisplatin | − | − | 26.5 ± 4.8 |

N/A, Not applicable.

*Tf (30 μM) and SA (600 μM) included in the cell-viability assay.

†Ti citrate is a mixture of species.

[TiO(HBED)]− Bioavailability Measurement in A549 Cells.

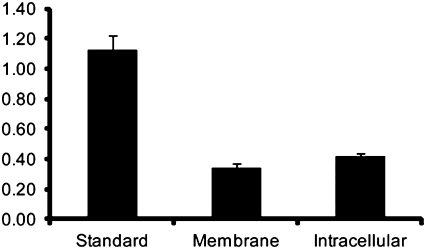

A549 cells were examined after incubation for 3 d in a solution of [TiO(HBED)]− at the IC50. Nearly 50% cell death was confirmed by the trypan blue exclusion assay, and the dead cells were microscopically observed not to be lysed (Fig. S7). The remaining live cells were fractionated into membrane and intracellular fractions. [TiO(HBED)]− was found to be slightly more abundant in the intracellular fraction at low-picomole amounts as determined by comparison with a 10-pmol [TiO(HBED)]− standard (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

LC-MS data for [TiO(HBED)]− in a 10-pmol standard and in the membrane and intracellular fractions of A549 cells (normalized areas). [TiO(HBED)]− is slightly more abundant in the intracellular fraction.

Discussion

Three Ti(IV) compounds with distinct ligands were studied to determine what factors influence their ability to induce cell death in A549 cells. A driving factor in the selection of these ligands was the nature of their binding to Ti(IV) in aqueous solution at pH 7.4. Previous work has shown that citrate (13, 39), naphthalene-2,3-diolate (20), and HBED (33) are able to form highly stable Ti(IV) compounds at physiological pH that protect Ti(IV) from the irreversible formation of TiO2. The ligands, however, display very different dissociation stabilities, as revealed by aqueous speciation studies. At pH 7.4 and micromolar concentrations, citrate serves as a bidentate ligand that is extremely labile and yields a mixture of Ti(IV) mono-, bis-, and tris-citrate species (13). The Ti(IV) center in these species likely has bound oxo/hydroxo ligands because of hydrolysis. The solution speciation stands in stark contrast to the very stable, monomeric, and unhydrolyzed solid-state tris-citrate species, [Ti(C6H4O7)3]8− (39). The bidentate naphthalene-2,3-diolate is significantly less labile than citrate is, predominantly forming the monomeric and unhydrolyzed Ti(IV) compound [Ti(C10H6O2)3]2−, comparable to the species crystallized at this pH.

An aqueous speciation study performed here reveals that HBED has a high affinity for Ti(IV) (Fig. 2) and exists as a 1:1 metal–ligand monomeric complex over a broad pH range (3–10) at micromolar concentrations (Fig. 2 and Fig. S3). At pH 7.4, partial HBED dissociation from the metal occurs, and an oxo or hydroxo ligand binds to it, as supported by electrospray MS (Fig. S4). This partially hydrolyzed but highly stable species predominates at this pH. The crystal structure (Fig. 1 and Tables S1 and S2) reveals that one of the phenolate oxygens is displaced and becomes protonated.

The bioactivity of the ligands is also of major interest because this property could play a role in governing the transport of Ti(IV) to, and possibly into, A549 cells. Citrate is an endogenous bioactive (40) molecule present at 100 μM in serum. There are well-characterized receptors that transport citrate into and throughout cells (40). HBED, although not endogenous, is also bioactive. HBED is a cell-permeable molecule that is a promising candidate for iron-overload disease therapy because of its high Fe(III) affinity (41). Ti(IV) compounds of diamine-bis(phenolato) ligands, which are related to HBED but lack the carboxylate appendages, display cytotoxic properties in different cell lines in vitro (14, 17, 19, 28, 42–44) and in a mouse cancer model in vivo (35). It is feasible that Ti(IV) compounds of citrate and HBED could use ligand-specific mechanisms for transport into cells. Naphthalene-2,3-diolate possesses no reported bioactivity.

Ligand polarity may be another critical factor controlling the transport of Ti(IV) compounds because of how it may affect interaction of the compounds with the serum proteins Tf and SA. Whereas Tf strips ligands from Ti(IV) when it binds the metal ion, SA can bind Ti(IV) compounds intact with ligands of varying polarity (6, 7). The polarity of the ligands, coupled with their dissociation stability, may discriminate Ti(IV) binding to one protein versus the other. Previous work at pH 7.4 showed that the stability constant of Ti(naphthalene-2,3-diolate)32− is so high that Tf is unable to bind the metal ion (20). The hydrophobic compound binds with fairly high affinity to SA, however. Ti(IV) citrate (a mixture of species) is able to competitively interact with both proteins, rapidly binding as an ion to Tf and as a Ti(IV) monocitrate complex to SA, likely in a hydrophilic pocket (13). This behavior of Ti(IV) citrate is comparable to that of titanocene dichloride, although the titanocene moiety would be expected to bind in a hydrophobic site in SA (13).

The interaction of [TiO(HBED)]− with Tf and SA was not previously explored. At pH 7.4, Tf and SA were dialyzed against [TiO(HBED)]− at micromolar concentrations. After dialyzing against metal-free buffer, the Ti(IV) content in the protein solutions was measured by a colorimetric assay (33). The test revealed the absence of Ti(IV). A UV-visible scan of the solutions displayed only apoproteins and no characteristics of ligand-to-metal charge-transfer bands attributable to coordinated Ti(IV) as an ion in Tf or a metal–ligand complex in SA (9, 13, 20, 33). Although this result could be expected for Tf because of HBED's high affinity for Ti(IV), the lack of Ti(IV) binding was hard to predict for the SA case. An Fe(III) compound of brominated HBED binds to SA but with low affinity (45). These findings suggest that Tf and SA will not play a role in the transport of [TiO(HBED)]− nor in the potential cytotoxicity exhibited by the compound.

The Ti(IV) compounds of citrate, naphthalene-2,3-diolate, and HBED were tested for their ability to induce cell death in A549 cells (Table 1). Cisplatin and titanocene dichloride were included in these experiments as positive and negative controls, respectively. [TiO(HBED)]− was the only compound to demonstrate a dose-dependent antiproliferative effect, which was also fairly potent (IC50 = 24.6 ± 0.8 μM; Fig. S5) and comparable to that of cisplatin (Table 1). The three compounds were also tested against the HL-60 leukemia and UACC-62 melanoma cells but demonstrated no cytotoxicity.

A549 cell-viability experiments were also performed on the ligands to distinguish any contribution to cell death made specifically by the ligands (Table 1). Citrate3− and naphthalene-2,3-diolate−, like their Ti(IV) compound counterparts, exhibited no cytotoxicity. HBED− did induce cell death (IC50 = 96.1 ± 15 μM; Fig. S5) but to a weaker extent than [TiO(HBED)]−. This result suggests that the cytotoxicity demonstrated by [TiO(HBED)]− may be a property of the compound as a whole.

We examined whether the potential trafficking roles played by Tf and SA have an influence on the activity of [TiO(HBED)]−. A549 cells were grown in 10% FBS, which includes low micromolar quantities of bovine Tf (46) and SA (bovine albumin ELISA kit; catalog no. 8000; Alpha Diagnostic International). These protein quantities were maintained throughout the cell-viability assays and should have been sufficient for the proteins to demonstrate an influence on the activity of the Ti(IV) complexes, especially if their role is as recyclable shuttling agents. The cytotoxicity of [TiO(HBED)]− was examined in the presence of serum physiological levels of human Tf (30 μM) and SA (600 μM), but no increase in activity was detected (Fig. S6 and Table 1). Instead, the potency was slightly weakened, perhaps because of nonspecific interactions with the proteins, an observation that is in agreement with the lack of detectable specific interactions at micromolar concentrations.

Tf and SA contributions to the cytotoxicity of Ti(IV) in A549 cells was further examined to determine the impact of these proteins on other Ti(IV) compounds. At serum physiological levels, Tf and SA similarly did not improve the poor cytotoxicity of titanocene dichloride (Table 1), in keeping with the results with [TiO(HBED)]−. We then tested preformed Ti(IV) protein compounds Ti2-Tf and titanocene-bound SA. Ti2-Tf was tested in two forms, an unhydrolyzed form where the metal center is bound by protein residue ligands and a synergistic anion (13) and a hydrolyzed form where the synergistic anion and/or a protein residue ligand is displaced by an oxo or hydroxo ligand (13, 38). Neither Ti2-Tf form displayed cytotoxicity nor did titanocene-bound SA (Table 1). These results strongly suggest that Ti(IV) cytotoxicity in A549 cells is not governed by Tf-directed pathways. Without surveying a broader collection of Ti(IV) compounds, it appears that SA also does not play a major role in the mechanism of Ti(IV)-based A549 cell death.

The evidence points to ligand identity being a critical factor in A549 cell antiproliferation by Ti(IV) compounds. Preventing ligand lability is not a major component. The Ti(IV) compound of naphthalene-2,3-diolate does not readily dissociate, and yet it does not demonstrate any antiproliferative behavior. The addition of excess citrate3− to serum physiological levels (100 μM) does not improve the cytotoxicity of the extremely labile Ti(IV) citrate. Where some degree of ligand coordination stability is important is to impede rapid binding of Ti(IV) to Tf. Both titanocene dichloride and Ti(IV) citrate rapidly deliver Ti(IV) to Tf (6, 9). In the case of Ti(IV) citrate, even in the presence of millimolar concentrations of free citrate, the exchange rate of Ti(IV) transfer to micromolar amounts of Tf is fast (9). We have already established that Ti2-Tf does not exhibit any cytotoxicity. If anything, Tf is an inhibitor of Ti(IV) cytotoxicity in A549 cells.

Ligand polarity also does not play a significant positive role. HBED, when bound to Ti(IV), presents a hydrophobic periphery that is intermediate between the very hydrophobic one of naphthalene-2,3-diolate and the hydrophilic one of citrate. Although it is hard to predict exactly how ligand polarity may influence the cytotoxicity of Ti(IV) compounds, we speculate that it could affect transport of the compounds into cells. It certainly can orient binding of the compounds to either hydrophobic or hydrophilic pockets of SA and provide a selective means to favor binding to SA over Ti(IV) transfer to Tf. However, binding of Ti(IV) compounds to SA is not well understood. In some cases, the binding interactions seem to be specific, as with the compounds of naphthalene-2,3-diolate (23) and citrate (13), although no binding sites have been identified. In others, the interactions seem to be nonspecific, as with titanocene dichloride (13). It is also not certain whether SA can deliver Ti(IV) compounds to cells or, if so, what type of compounds. Nonetheless, binding to SA appears to aid in A549 cell survival. Consequently, SA may behave like Tf, as an inhibitor of Ti(IV) antiproliferation.

The ligand properties governing the cytotoxicity of [TiO(HBED)]− in A549 cells are a combination of coordination stability, no serum protein binding, and bioactivity. [TiO(HBED)]− is quite stable at pH 7.4. This factor is key to the inability of Tf to remove Ti(IV) from the compound. [TiO(HBED)]− also does not bind to SA. Independent routes must be used by the compound to exhibit its cytotoxicity on A549 cells. It is highly probable that these routes are the same as those used by the metal-free ligand to penetrate cells and chelate Fe(III) in diseases related to iron overload (41). In support of this possibility is that the charge state of [TiO(HBED)]− is the same as that of HBED− at pH 7.4 (47). If the mechanism of entry depends on electrostatic interactions, then both the ligand and compound could use the same pathway.

For a preliminary insight into the mechanism of A549 cell death induced by [TiO(HBED)]−, we examined whether [TiO(HBED)]− is transported into the cells and what effect the compound has on the integrity of the cells. A549 cells were incubated for 3 d in 25 μM [TiO(HBED)]−, the IC50. Nearly 50% cell death was confirmed by a trypan blue exclusion assay. A microscopic image of the cells showed that the dead cells (those not bound to the plate) are not lysed (Fig. S7), suggesting that [TiO(HBED)]− does not operate by triggering cell lysis and that it operates by interfering with intracellular metabolic pathways.

The unbound cells were removed by washing, and the live cells were separated into membrane and intracellular fractions. A liquid chromatography/MS (LC-MS) platform was used to detect [TiO(HBED)]− in both fractions. A 10-pmol standard of the compound was run to estimate the amount of [TiO(HBED)]− present in both fractions. The complex was detected at comparable low-picomole levels in the membrane and intracellular fractions in the form of [Ti(HBED)] (Fig. 3); this species is dominant at pH 3.0, which is the pH used to operate the LC. This finding is remarkable because it shows that an intact Ti(IV) compound penetrates a cell (Fig. 3) and likely uses intracellular pathways to exhibit its effect.

This work is an important demonstration of a water-soluble, solution-stable Ti(IV) compound that exhibits anticancer activity independent of serum protein interaction. Cytotoxicity tests against A549 cells reveal that the nature of the chelating ligand is crucial to the activity of [TiO(HBED)]−. HBED is bioactive and forms a Ti(IV) compound that is void of extensive hydrolysis at pH 7.4. A HBED-specific pathway may be implicated in the transport of [TiO(HBED)]− into A549 cells. The localization of [TiO(HBED)]− in A549 cells and the mechanism by which it exhibits its effect are undefined and require further exploration. It is very plausible that [TiO(HBED)]− operates by a synergism of the antiproliferation afforded by Ti(IV) and HBED. [TiO(HBED)]− does not exhibit cytotoxicity against HL-60 leukemia cells and UACC-62 melanoma cells. It will be interesting to investigate other cell types that [TiO(HBED)]− is active against and whether it operates by a similar mechanism of action. Future studies are also warranted to explore the anticancer properties of other bioactive ligands and HBED derivatives that form stable, well-defined solution Ti(IV) compounds, possess specific cellular target sites, and are cytotoxic. These studies will contribute to the improvement in the drug design strategies for metal-based anticancer therapeutics.

Materials and Methods

All sources for chemicals, proteins, and Ti(IV) as well as any compound synthesis are described in SI Materials and Methods.

Instrumentation.

UV-visible spectra were recorded on a Cary 50 spectrophotometer (Varian). Multiwell plate absorbances were measured in a Gemini 384 plate reader. FTIR spectra (KBr pellets) were collected on a Nicolet 6700 spectrometer. Electrospray mass spectra were collected on a Waters/Micromass ZQ spectrometer. LC-MS data were collected with a NanoLC-2D (Eksigent Technologies) system coupled to a ThermoFinnigan LTQ mass spectrometer.

Spectropotentiometric Titration.

Spectropotentiometric titrations were performed on 200 μM HBED and Ti(HBED). The ligand and Ti(IV) compound solutions (50 mL) contained 2.6% DMF and 0.1 M KCl. The titrations were performed under Ar from pH 3.0 to pH 10.0 and then reverse-titrated. Relative binding affinities were determined with SpecFit 3.0.36 (Spectrum Software Associates). Ligand protonation values and ligand spectra at different protonation states were used to deconvolute the spectropotentiometric data (Fig. S3). The best fit model was determined after considering all chemically reasonable metal–ligand species and the spectroscopic characteristics of the synthesized Ti(IV) HBED compounds. All metal species are defined in terms of the total metal, ligand, and proton stoichiometry (MLH).

Cytotoxicity Studies.

A549 cytotoxicity by the compounds was evaluated by using the colorimetric 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. Cells >95% confluence [grown in 100 × 20 mm tissue-culture dishes (BD Falcon)] were seeded into 96-well plates in DMEM in a volume of 100 μL at 1.0 × 104 cells per well on day 0. After a 24-h incubation at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% (vol/vol) CO2, Ti(IV) compounds, proteins, and ligands were added in a volume of 100 μL to bring the total volume of culture media in the wells to 200 μL. All solutions and dilutions of the compounds were prepared in respective buffers immediately before addition to the cultured cells to limit the possibility of precipitation upon standing. Final concentrations achieved in treated wells were 0.1–100 μM in initial screening assays and 0.1–1 mM in subsequent assays. Each compound concentration was added to four replicate wells. The plates were incubated for 3 d at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% (vol/vol) CO2. At 3 h before completion of the incubation time, 100 μL of medium was removed from each well, and 100 μL of MTT (Research Organics) solution (2 mg/mL in PBS) was added. The plates were kept protected from light and were then incubated at 37 °C for 3 h. Subsequently, 75 μL of the solution was removed and 100 μL of 10% SDS (in 0.01 M HCl) was added to each well. The plates were returned to the incubator to allow adequate time for dissolution of the formazan crystals formed by MTT reduction. The absorbance of the solutions was measured at 570 nm, corrected for the reference wavelength at 690 nm. The IC50 value was determined from dose–response curves. Cytotoxicity assays using HL-60 and UACC-62 cells were performed in the laboratory of Paul J. Hergenrother at the University of Illinois, Urbana, IL.

[TiO(HBED)]− Interaction with A549 Cells.

Lysis was examined as a method of A549 cell death induced by [TiO(HBED)]−. Confluent A549 cells were transferred to 100 × 20 mm tissue-culture dishes at a density of 1 × 107 cells per plate. Three plates were treated with 25 μM [TiO(HBED)]−, and three were treated with the corresponding amount of buffer [0.1 M Hepes and 0.1 M NaCl (pH 7.4)]. The plates were incubated for 3 d at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% (vol/vol) CO2. A trypan blue exclusion assay was performed to determine cell death. An image of the two sets of cells was collected with a VistaVision microscope (VWR).

The membrane and intracellular fractions of the plate-bound cells were separated as described in SI Materials and Methods. The final membrane and intracellular samples were dissolved in 200 μL of 0.1% formic acid (aqueous), which included 10% DMF. A 1 pmol/μL [TiO(HBED)]− solution was also prepared in the same solution. The samples were analyzed with an LTQ mass spectrometer. The analytical column (self-pack PicoFRIT column, 75 μm i.d.; New Objective) was packed to 15 cm with 3 μM C18 (Magic C18AQ, 200 Å; Michrom Bioresources). The trap column was obtained prepacked from New Objective (IntegraFRIT sample trap, C18, 5 μm, 100 μm column i.d.). A 10-μL injection of the samples and [TiO(HBED)]− standard was performed in triplicate. The samples were trapped at an isocratic flow rate of 2 μL/min for 10 min and eluted at a flow rate of 300 nL/min via a mobile phase gradient of 5–100% B in 1 h (mobile phase A: 0.1% formic acid (aqueous); mobile phase B: 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile). The MS experiments were performed in the positive mode. The mass range for data acquisition was set from m/z 200 to 600. The data were analyzed by MS and Ti isotope distribution matching.

More details on synthetic, crystallographic, spectropotentiometric, and protein- and cell-based experiments for [TiO(HBED)]− as well as a thorough description of solution preparation for A549 cytotoxicity experiments are provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Paul J. Hergenrother for his assistance with the cytotoxicity studies. We are grateful for the constructive insight provided by Cynthia W. Peterson, Sarah Slavoff, and Yun-Gon Kim. Funding was provided by the Thomas Shortman Training, Scholarship, and Safety Fund and The Mary Fieser Postdoctoral Fellowship (to A.D.T.); American Cancer Society Research Scholar Grant RSG-06-246-01-CDD (to A.M.V.); and the Burroughs Wellcome Fund Career Award in the Biomedical Sciences (to A.S.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: Crystallographic data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Cambridge Structural Database, Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, United Kingdom (CSD reference no. CCDC846178).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1119303109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Rosenberg B, VanCamp L, Trosko JE, Mansour VH. Platinium compounds: A new class of potent antitumour agents. Nature. 1969;222:385–386. doi: 10.1038/222385a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siddik ZH. Cisplatin: Mode of cytotoxic action and molecular basis of resistance. Oncogene. 2003;22:7265–7279. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caruso F, Rossi M. Antitumor titanium compounds. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2004;4:49–60. doi: 10.2174/1389557043487565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olszewski U, Hamilton G. Mechanisms of cytotoxicity of anticancer titanocenes. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2010;10:302–311. doi: 10.2174/187152010791162261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dyson PJ, Sava G. Metal-based antitumour drugs in the post genomic era. Dalton Trans. 2006;16:1929–1933. doi: 10.1039/b601840h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo ML, Sun HZ, McArdle HJ, Gambling L, Sadler PJ. TiIV uptake and release by human serum transferrin and recognition of TiIV-transferrin by cancer cells: Understanding the mechanism of action of the anticancer drug titanocene dichloride. Biochemistry. 2000;39:10023–10033. doi: 10.1021/bi000798z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams J, Moreton K. Distribution of iron between the metal-binding sites of transferrin in human serum. Biochem J. 1980;185:483–488. doi: 10.1042/bj1850483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li HY, Sadler PJ, Sun HZ. Rationalization of the strength of metal binding to human serum transferrin. Eur J Biochem. 1996;242:387–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0387r.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tinoco AD, Valentine AM. Ti(IV) binds to human serum transferrin more tightly than does Fe(III) J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:11218–11219. doi: 10.1021/ja052768v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aarabi MH, Mirhashemi SM, Ani M, Moshtaghie AA. Comparative binding studies of titanium and iron to human serum transferrin. Asian J Biochem. 2011;6:191–199. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nuevo-Ordonez Y, Montes-Bayon M, Gonzalez EB, Sanz-Medel A. Titanium preferential binding sites in human serum transferrin at physiological concentrations. Metallomics. 2011;3:1297–1303. doi: 10.1039/c1mt00109d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keer HN, et al. Elevated transferrin receptor content in human prostate cancer cell lines assessed in vitro and in vivo. J Urol. 1990;143:381–385. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)39970-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tinoco AD, Eames EV, Valentine AM. Reconsideration of serum Ti(IV) transport: Albumin and transferrin trafficking of Ti(IV) and its complexes. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:2262–2270. doi: 10.1021/ja076364+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shavit M, Peri D, Melman A, Tshuva EY. Antitumor reactivity of non-metallocene titanium complexes of oxygen-based ligands: Is ligand lability essential? J Biol Inorg Chem. 2007;12:825–830. doi: 10.1007/s00775-007-0236-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao LM, Hernandez R, Matta J, Melendez E. Synthesis, Ti(IV) intake by apotransferrin and cytotoxic properties of functionalized titanocene dichlorides. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2007;12:959–967. doi: 10.1007/s00775-007-0268-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hernandez R, et al. Structure-activity studies of Ti(IV) complexes: Aqueous stability and cytotoxic properties in colon cancer HT-29 cells. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2008;13:685–692. doi: 10.1007/s00775-008-0353-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tshuva EY, Ashenhurst JA. Cytotoxic titanium(IV) complexes: Renaissance. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2009;2009:2203–2218. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tshuva EY, Peri D. Modern cytotoxic titanium(IV) complexes; Insights on the enigmatic involvement of hydrolysis. Coord Chem Rev. 2009;253:2098–2115. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Immel TA, Groth U, Huhn T. Cytotoxic titanium salan complexes: Surprising interaction of salan and alkoxy ligands. Chemistry. 2010;16:2775–2789. doi: 10.1002/chem.200902312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tinoco AD, Eames EV, Incarvito CD, Valentine AM. Hydrolytic metal with a hydrophobic periphery: Titanium(IV) complexes of naphthalene-2,3-diolate, and interactions with serum albumin. Inorg Chem. 2008;47:8380–8390. doi: 10.1021/ic800529v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kratz F. Albumin as a drug carrier: Design of prodrugs, drug conjugates and nanoparticles. J Control Release. 2008;132:171–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ravera M, Gabano E, Baracco S, Osella D. Electrochemical evaluation of the interaction between antitumoral titanocene dichloride and biomolecules. Inorg Chim Acta. 2009;362:1303–1306. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pavlaki M, et al. A proposed mechanism for the inhibitory effect of the anticancer agent titanocene dichloride on tumour gelatinases and other proteolytic enzymes. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2009;14:947–957. doi: 10.1007/s00775-009-0507-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vessieres A, et al. Proliferative and anti-proliferative effects of titanium-and iron-based metallocene anti-cancer drugs. J Organomet Chem. 2009;694:874–879. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eger S, et al. Titanocene difluorides with improved cytotoxic activity. Inorg Chem. 2010;49:1292–1294. doi: 10.1021/ic9022163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hogan M, Claffey J, Pampillon C, Watson RWG, Tacke M. Synthesis and cytotoxicity studies of new dimethylamino-functionalized and azole-substituted titanocene anticancer drugs. Organometallics. 2007;26:2501–2506. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peri D, Meker S, Manna CM, Tshuva EY. Different ortho and para electronic effects on hydrolysis and cytotoxicity of diamino bis(phenolato) “salan” Ti(IV) complexes. Inorg Chem. 2011;50:1030–1038. doi: 10.1021/ic101693v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manna CM, Armony G, Tshuva EY. New insights on the active species and mechanism of cytotoxicity of salan-Ti(IV) complexes: A stereochemical study. Inorg Chem. 2011;50:10284–10291. doi: 10.1021/ic201340m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manna CM, Tshuva EY. Markedly different cytotoxicity of the two enantiomers of C2-symmetrical Ti(IV) phenolato complexes; mechanistic implications. Dalton Trans. 2010;39:1182–1184. doi: 10.1039/b920786b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Potter GD, Baird MC, Chan M, Cole SPC. Cellular toxicities of new titanocene dichloride derivatives containing pendant cyclic alkylammonium groups. Inorg Chem Commun. 2006;9:1114–1116. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaluderovic GN, et al. Synthesis, characterization and biological studies of alkenyl-substituted titanocene(IV) carboxylate complexes. Appl Organomet Chem. 2010;24:656–662. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Potter GD, Baird MC, Cole SPC. A new series of titanocene dichloride derivatives bearing chiral alkylammonium groups; assessment of their cytotoxic properties. Inorg Chim Acta. 2010;364:16–22. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tinoco AD, Incarvito CD, Valentine AM. Calorimetric, spectroscopic, and model studies provide insight into the transport of Ti(IV) by human serum transferrin. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:3444–3454. doi: 10.1021/ja068149j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bodner A, et al. Mono- and dinuclear titanium(III)/titanium(IV) complexes with 1,4,7-trimethyl-1,4,7-triazacyclononane (L). Crystal structures of a compositionally disordered green and a blue form of [LTiCl3]. Structures of [LTi(O)(NCS)2], [LTi(OCH3)Br2](ClO4), and [L2Ti2(O)2F2(μ-F)](PF6) Inorg Chem. 1992;31:3737–3748. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jeske P, Haselhorst G, Weyhermuller T, Wieghardt K, Nuber B. Synthesis and characterization of mononuclear octahedral titanium(IV) complexes containing Ti=O, Ti(O2), and Ti(OCH3)x (x = 1–3) structural units. Inorg Chem. 1994;33:2462–2471. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crescenzi R, Solari E, Floriani C, Chiesi-Villa A, Rizzoli C. Binding of a meso-octaethyl tris(pyrrole)-mono(pyridine) ligand to titanium(III) and titanium(IV): A monomeric titanium(IV) oxo bis(pyridine)-bis(pyrrole) complex derived from the C-O bond cleavage of carbon monoxide. Organometallics. 1996;15:5456–5458. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hagadorn JR, Arnold J. Titanium(II), -(III), and -(IV) complexes supported by benzamidinate ligands. Organometallics. 1998;17:1355–1368. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guo ML, Harvey I, Campopiano DJ, Sadler PJ. Short oxo-titanium(IV) bond in bacterial transferrin: A protein target for metalloantibiotics. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:2758–2761. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Collins JM, Uppal R, Incarvito CD, Valentine AM. Titanium(IV) citrate speciation and structure under environmentally and biologically relevant conditions. Inorg Chem. 2005;44:3431–3440. doi: 10.1021/ic048158y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mycielska ME, et al. Citrate transport and metabolism in mammalian cells: Prostate epithelial cells and prostate cancer. Bioessays. 2009;31:10–20. doi: 10.1002/bies.080137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Birch N, Wang X, Chong HS. Iron chelators as therapeutic iron depletion agents. Expert Opin Ther Patents. 2006;16:1533–1556. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Immel TA, Groth U, Huhn T, Ohlschlager P. Titanium salan complexes displays strong antitumor properties in vitro and in vivo in mice. PLoS ONE. 2011;6::e17869. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tzubery A, Tshuva EY. Trans titanium(IV) complexes of salen ligands exhibit high antitumor activity. Inorg Chem. 2011;50:7946–7948. doi: 10.1021/ic201296h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Glasner H, Tshuva EY. A marked synergistic effect in antitumor activity of salan titanium(IV) complexes bearing two differently substituted aromatic rings. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:16812–16814. doi: 10.1021/ja208219f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jenkins BG, Armstrong E, Lauffer RB. Site-specific water proton relaxation enhancement of iron(III) chelates noncovalently bound to human serum albumin. Magn Reson Med. 1991;17:164–178. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910170120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kakuta K, Orino K, Yamamoto S, Watanabe K. High levels of ferritin and its iron in fetal bovine serum. Comp Biochem Physiol A Physiol. 1997;118:165–169. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9629(96)00403-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rajan KS, Murase I, Martell AE. New multidentate ligands. VII. Ethylenediamine-N,N′-diacetic-N,N′-di(methlenephosphonic)acid. J Am Chem Soc. 1969;91:4408–4412. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.