Abstract

Synapse formation is considered to be crucial for learning and memory. Understanding the underlying molecular mechanisms of synapse formation is a key to understanding learning and memory. Kalirin-7, a major isoform of Kalirin in adult rodent brain, is an essential component of mature excitatory synapses. Kalirin-7 interacts with multiple PDZ-domain-containing proteins including PSD95, spinophilin, and GluR1 through its PDZ-binding motif. In cultured hippocampal/cortical neurons, overexpression of Kalirin-7 increases spine density and spine size whereas reduction of endogenous Kalirin-7 expression decreases synapse number, and spine density. In Kalirin-7 knockout mice, spine length, synapse number, and postsynaptic density (PSD) size are decreased in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons; these morphological alterations are accompanied by a deficiency in long-term potentiation (LTP) and a decreased spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic current (sEPSC) frequency. Human Kalirin-7, also known as Duo or Huntingtin-associated protein-interacting protein (HAPIP), is equivalent to rat Kalirin-7. Recent studies show that Kalirin is relevant to many human diseases such as Huntington's Disease, Alzheimer's Disease, ischemic stroke, schizophrenia, depression, and cocaine addiction. This paper summarizes our recent understanding of Kalirin function.

1. Kalirin Is a Rho Guanine Nucleotide Exchange Factor (GEF)

Kalirin was discovered 15 years ago as a novel protein that interacts with the cytosolic carboxyl-terminal of peptidylglycine α-amidating monooxygenase (PAM), an integral membrane peptide processing enzyme [1]. We have made significant progress in understanding the functions of Kalirin; like the many other Rho-GEFs encoded in mammalian genomes, Kalirin promotes the exchange of GDP for GTP and thus stimulates the activity of specific Rho GTPases [2, 3]. Rho GTPases that regulate multiple cellular processes play a key role in transducing signals from extracellular stimuli to the intracellular pathways that play a pivotal role in the formation of dendritic spines and synaptic development [4–6].

2. Multiple Kalirin Isoforms

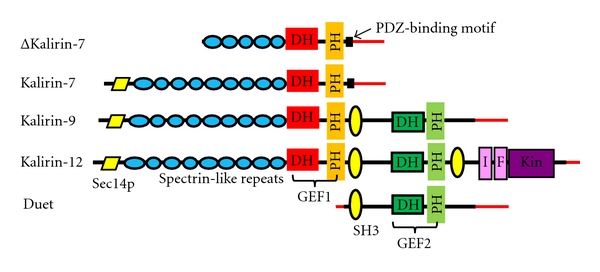

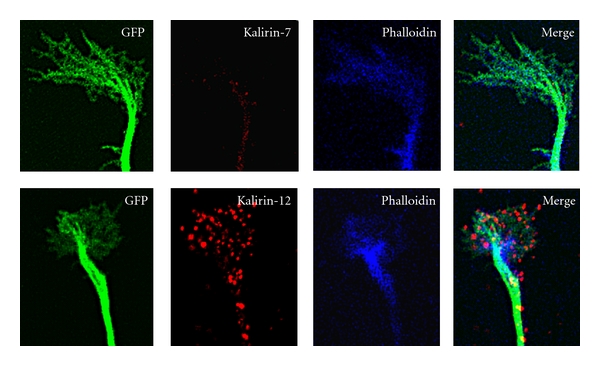

The mouse Kalirin gene (Kalrn) consists of 65 exons spanning >650 kb of the genome; the presence of multiple promoters and transcriptional start sites enables the production of multiple functional isoforms of Kalirin [7–9]. Each Kalirin isoform is composed of a unique collection of domains (Figure 1). Major Kalirin isoforms including Kalirin-7, -9, and -12 are generated through the use of alternative 3′ exons [8]. The major isoforms share some common features including nine spectrin-like repeats, the GEF1 domain and the Sec14p domain. Sec14p domains facilitate lipid interactions and cellular localization. The nine spectrin-like repeat regions that follow the Sec14p domain have been shown to interact with many proteins including disrupted in schizophrenia 1 (DISC1) [10], peptidylglycine α-amidating monooxygenase (PAM) [1], inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) [11], Huntingtin-associated protein 1 (HAP1) [12], and Arf6 (ADP-ribosylation factor 6) [13]. Kalirin-12 is the longest isoform and contains additional domains that include GEF2, an immunoglobulin-like (Ig) domain, a fibronectin III (FnIII) domain, and a serine/threonine protein kinase domain that is followed by a short, unique carboxyl-terminus [7, 14]. Kalirin-12 is found in the growth cones of immature neurons (Figure 2) and dendritic spines of mature cultured hippocampal neurons, suggesting a role for Kalirin-12 in axon outgrowth and synaptic plasticity. Interaction of the Ig-FnIII region unique to Kalirin-12 with the GTPase domain of dynamin may facilitate the coordination of endocytic trafficking and changes in the actin cytoskeleton [15]. Endogenous Kalirin-9 is localized to neurites and growth cones, and expression of exogenous Kalirin-9 induces longer neurites and altered neuronal morphology in cultured cortical neurons [16]. The functions of Kalirin-9 and Kalirin-12 in neurons remain to be elucidated. The ΔKalirin-7 (also referred as Kalirin-5) isoform is generated using a different promoter, and translation initiation begins at the start of spectrin-like repeat 5, producing an isoform with only 5 spectrin-like repeats. Overexpression of ΔKalirin-7 results in an increase in spine size, but not spine density, in cultured cortical neurons [17]. Duet, an isoform of Kalirin that begins just before the second GEF domain and continues through the unique C-terminal of Kalirin-12, uses a third promoter [7]. Duet was discovered as a protein homologous to the catalytic domain of death associated protein kinase and is localized to actin-associated cytoskeletal elements, suggesting the involvement of Duet in cytoskeleton-dependent functions [18].

Figure 1.

Major Kalirin isoforms. Alternative splicing generates different isoforms of Kalirin. DH: Dbl homology; PH: pleckstrin homology; GEF1: guanine nucleotide exchange factor 1; SH3: Src homology domain; GEF2: guanine nucleotide exchange factor 2; I: immunoglobulin-like; F: fibronectin III-like; Kin: kinase domain; red lines, unique 5′- and 3′-untranslated regions.

Figure 2.

Kalirin-12, not Kalirin-7, is localized to the growth cone of hippocampal neurons. Primary cultures of hippocampal neurons prepared at embryonic day 20 (E20) were transfected with a vector encoding GFP on the day of culture preparation as described [19]. On day 3 after transfection, cultures were fixed for staining of filamentous actin with Alexa Fluor 633 Phalloidin (Life Technologies) and endogenous Kalirin-7 or Kalirin-12 with isoform-specific rabbit antibodies. Rabbit antibodies were visualized using Cy3 donkey anti-rabbit IgG (The Jackson Laboratory). Images were collected with a Zeiss confocal microscope LSM510.

3. Tissue Expression

Kalirin expression is detectable in a wide array of adult tissues including neurons, endocrine cells, liver, muscle, and heart [2, 20, 21]. In addition, developmentally regulated, tissue specific-Kalirin isoform expression is evident. Kalirin-9 and -12 are highly expressed in neuronal tissue during embryonic development, while in the adult brain expression of each is drastically decreased; a concomitant increase in Kalirin-7 expression occurs [8, 20, 22]. Kalirin-7 expression is largely limited to neurons of the central nervous system; its levels are extremely low at birth (postnatal days 1–7) and begin to increase markedly at postnatal day 14, which coincides with the onset of maximum synaptogenesis [22, 23].

4. Kalirin-7 Is the Major Kalirin Isoform in Adult Brain

Kalirin-7 is the most abundant Kalirin isoform in the adult rodent brain and is exclusively localized to the postsynaptic side of excitatory synapses [19, 22, 39, 40]. Kalirin-7 is a multifaceted molecule containing domains that interact with a wide array of molecular machinery. The Sec14p domain located at the N-terminus interacts with phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate and plays a key role in Kalirin-7-mediated spine morphogenesis (Ma et al., unpublished). The C-terminus of Kalirin-7 contains a unique PDZ-binding motif through which Kalirin-7 interacts with PDZ-domain-containing proteins including PSD-95, AF-6, and spinophilin [39]. Binding of the NMDA receptor subunit NR2B to the PH domain of Kalirin-7 is important for normal synaptic plasticity [41]. The spectrin-like domains of Kalirin-7 through which it interacts with DISC1, iNOS, PAM, HAP1, and Arf6 play a key role in Kalirin-7-induced synapse formation (Ma et al., unpublished). The nucleotide sequences of human Kalirin-7 (Duo) and rat Kalirin-7 are 91% identical, and their amino acid sequences are 98% identical; human Kalirin-7 contains a 27-nucleotide insert not found in rat Kalirin-7, located at the end of the region encoding the seventh spectrin repeat [8, 12].

5. Kalirin-7 Contains Multiple Phosphorylation Sites

Phosphorylation of Kalirin-7 has recently been shown to be a pivotal mechanism mediating Kalirin-7-induced spine formation and synaptic plasticity [42–44]. Purified PKA, PKC, CaMKII, Cdk5, and Fyn each phosphorylate purified Kalirin-7 [45]. Kalirin-7 is extensively phosphorylated in vivo. The phosphorylation sites identified in vitro using purified CaMKII, PKA, PKC, or CKII, identified only 5 of the 22 sites that undergo phosphorylation in cells or tissue. These findings emphasize a critical role for additional protein kinases and the importance of cellular localization in the phosphorylation of Kalirin-7 [45]. Densely distributed phosphorylation sites have been identified in the spectrin-like repeat region, many lying on the fourth and fifth repeats. Their phosphorylation state could influence on a wide array of protein-protein interactions that involve this region. Since the first four spectrin-like repeats are absent in ΔKalirin-7 (Figure 1), the phosphorylation sites in the missing region could play a key role in the differences in spine size and density associated with expression of full length Kalirin-7 versus ΔKalirin-7. Overexpression of exogenous Kalirin-7 results in an increase in both spine density and spine size while overexpression of ΔKalirin-7 only increases spine size without altering spine density [17]. Although phosphorylation sites that regulate GEF activity as assessed in intact cells have been identified, a relationship between phosphorylation state and GEF activity has not yet been demonstrated using purified proteins.

6. Kalirin-7 Plays a Key Role in Spine/Synapse Formation In Vitro

Kalirin-7 expression is limited to neurons in the CNS [22, 30, 46]. Immunostaining in cultured hippocampal and cortical neurons demonstrates that Kalirin-7 clusters are apposed to glutamate-transporter-1-(Vglut1-) positive clusters, a marker for excitatory presynaptic terminals [19, 47, 48]. When cultured neurons are fixed with cold methanol, it can be seen that the Kalirin-7 positive clusters consistently overlap clusters positive for PSD95, NMDA receptor subunits NR1 and NR2B, or AMPA receptor subunits GluR1 and GluR2; overlap is apparent in both dendritic spines and in the dendritic shaft [19, 40]. In contrast, Kalirin-7 clusters neither align with GAD65-positive clusters, a marker for inhibitory presynaptic terminals, nor with GABAA receptor positive clusters, a marker for inhibitory postsynaptic endings [19]. These findings lead to the conclusion that Kalirin-7 is localized almost entirely to postsynaptic excitatory terminals.

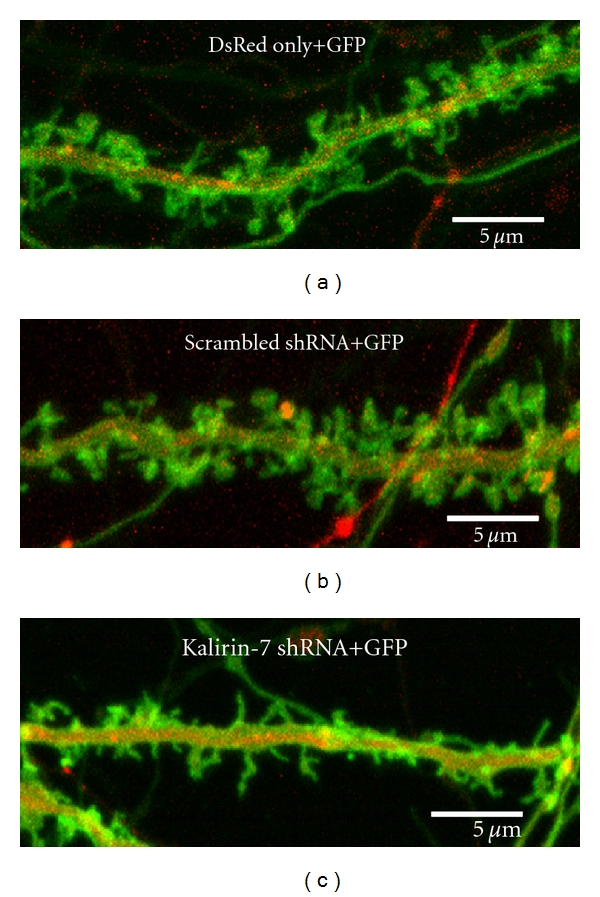

Regulation of Kalirin-7 expression by synaptic activity in hippocampal neurons suggests that Kalirin-7 plays a pivotal role in the regulation of excitatory synapse formation and signaling [40, 42]. Overexpression of Kalirin-7 causes an increase in dendritic spine density, spine size, and synapse number, while reduction of endogenous Kalirin-7 levels leads to a reduction in spine density, spine size, and synapse number in cultured hippocampal and cortical neurons [19, 22, 39] (Figure 3). Interestingly, overexpression of Kalirin-7 induces spine formation in spine-free hippocampal interneurons [19] and a recent study reports an important role of Kalirin-7 in regulating dendrite growth in cortical interneurons [44]. A delicate balance between synaptic excitation and inhibition is critical for maintaining normal circuits in the CNS, and interneurons play an essential role in regulating local circuit excitability [49]. Understanding Kalirin-7 function in interneurons may increase our understanding of neurological diseases such as epilepsy, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, autism, and Alzheimer's Disease, which are related to disruption of GABAergic interneuron development [50–53].

Figure 3.

Expression of Kalirin-7 shRNA causes a reduction in spine density and spine size in cultured hippocampal neurons. Cultured hippocampal neurons prepared at E20 were transfected with vector encoding a membrane-tethered version of GFP (pmGFP) alone [(a), spine density 8.9 ± 0.8/10 μm], pmGFP plus a scrambled shRNA [(b), spine density 9.2 ± 0.9/10 μm], or pmGFP plus pSIREN-Kalirin-7 shRNA [(c), spine density 5.2 ± 0.6/10 μm] on the day of culture preparation. The specificity of pSIREN-Kalirin-7 shRNA was determined previously [19]. DsRed marks transfected neurons expressing the shRNA. Images were collected on day 20 with an LSM510 confocal microscope. Expression of Kalirin-7 shRNA, not scrambled shRNA, caused a 80% decrease in Kalirin-7 staining (not shown). Spine density was determined using Metamorph (Molecular Devices, Downington, PA) as described [54]. Scale bar = 5 μm.

7. Kalirin-7 Plays a Key Role in Spine/Synapse Formation In Vivo

Two Kalrn knockout mouse models have been developed: the Kalirin-7 knockout mouse (Kalirin-7KO) [54] and the GEF1 Kalirin knockout mouse (KalirinGEF1-KO) [55]. Kalirin-7KO mice, in which the terminal exon unique to Kalirin-7 was deleted, grow and reproduce normally. Hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons of Kalirin-7KO mice show a 15% decrease in spine density and deficits in long-term potentiation (LTP). Morphological alterations in Kalirin-7KO mice are accompanied by behavioral alterations including decreased anxiety-like behavior in the elevated zero maze and impaired acquisition of a passive avoidance task. Kalirin-7KO mice exhibit normal behavior in the open field, object recognition, and radial arm maze tasks [54]. PSDs purified from the cortices of Kalirin-7KO mice show a deficit in Cdk5, a kinase known to phosphorylate Kalirin-7 and play an essential role in Kalirin-7-mediated spine formation and synaptic function [43, 54, 56]. Furthermore, NR2B levels are modestly decreased in PSD preparations from the cortices of Kalirin-7KO animals [54]. This decrease is accompanied by decreased levels of NR2B-dependent NMDA receptor currents in cortical pyramidal neurons [41]. NR2B plays a critical role in LTP induction, dendritic spine formation, different forms of synaptic plasticity, learning, and memory [57–60]. Decreased NR2B levels may partially contribute to decreased spine density and the deficit in LTP induction observed in Kalirin-7KO mice. Importantly, expression of exogenous Kalirin-7 in cultured Kalirin-7KO neurons rescues decreased spine density. These findings show that Kalirin-7 plays an essential role in synaptic structure and function.

The KalirinGEF1-KO mice were generated by replacing exons 27-28 in the first GEF domain by a neomycin resistance cassette, thus eliminating production of the major Kalirin isoforms; in addition to Kalirin-7, these mice are unable to produce Kalirin-9 and Kalirin-12 [55]. KalirinGEF1-KO mice show significant morphological deficits including reduced size of both cortex and decreased spine density in pyramidal neurons of the cortex [55]. Interestingly, in KalirinGEF1-KO mice the hippocampus is reduced in size but spine density in hippocampal neurons is normal. This reduction in hippocampal size in KalirinGEF1-KO mice results from neuronal loss since Kalirin is exclusively expressed in pyramidal neurons, granule cells of the dentate gyrus, and interneurons scattered throughout the hippocampus [19, 22, 46, 54]. Both Kalirin-7KO and KalirinGEF1-KO mice show impaired hippocampal LTP induction, impaired contextual fear conditioning, and reduced spine density in cultured cortical neurons and normal long-term memory [54, 61]. KalirinGEF1-KO mice show deficits in working memory and an intact reference memory. However, Kalirin-7KO and KalirinGEF1-KO mice exhibit distinct differences in their behavioral phenotype. KalirinGEF1-KO mice show very high locomotor activity in the open field and a deficit in spatial memory, which are not affected in Kalirin-7KO mice [54, 55]. Further comparisons of the phenotypes of the KalirinGEF1-KO and Kalirin-7KO mice are needed, along with the generation of additional Kalrn knockout mouse models generated using different knockout strategies.

8. Kalirin-7 Is Implicated in Cocaine Addiction

Cocaine addiction is a chronic relapsing neurological disorder associated with severe medical and psychosocial complications [62–66]. The long-lasting nature of cocaine addiction leads to relapse and makes it especially difficult to treat [21]. Repeated cocaine treatments increase dendritic spine density/spine head size and neurite complexity in the brain's reward circuitry such as the medium spiny neurons (MSNs) of the nucleus accumbens (NAc). Our study shows that Kalirin-7 is an essential determinant of dendritic spine formation following cocaine treatment [38]. Kalirin-7 is expressed in the MSNs of the NAc, a key area in the brain involved in drug addiction and reward pathways [37]. Chronic cocaine treatment of wild-type mice results in an increase in Kalirin-7 expression in the NAc which is accompanied by an increase in spine density in the MSNs of NAc core [37, 67]. This cocaine-induced increase in dendritic spine density in the NAc MSNs in wild-type mice is abolished in Kalirin-7KO mice. Both wild-type and Kalirin-7KO mice have identical spine densities in the MSNs of the NAc prior to cocaine treatment. These morphological changes could underlie the behavioral variations seen in these mice following cocaine treatment. Chronic cocaine treatment leads to increased locomotor sensitization in Kalirin-7KO mice compared to wild-type controls [38]. These data suggest Kalirin-7 plays an important role in the mechanism of cocaine addiction, which needs to be addressed in the future.

9. Kalirin Is Implicated in Human Diseases

Altered Kalirin expression has been reported in several neuropsychiatric, neurological and cardiovascular diseases as well as animal models of depression, epilepsy and cocaine addiction (Table 1). Genetic analyses have identified KALRN as a major risk factor in stroke and early onset of coronary artery disease [34–36]. Similarly in schizophrenia, decreased dendritic spine density in the prefrontal cortex is reported to correlate with decreased Kalirin mRNA levels [24]. A rare missense mutation in the KALRN gene has been shown to be a genetic risk factor for schizophrenia [26]. The spectrin-like repeat region of Kalirin has also been shown to interact with DISC1, a genetic risk factor for schizophrenia which plays an important role in activity-dependent spine elongation by promoting Kalirin-7/Rac-1 interactions [10, 24, 68, 69]. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is the most common neurobehavioral disorder and the underlying molecular mechanisms of ADHD are largely unknown. Animal models of ADHD are associated with spine loss in striatal MSNs [70] and functional impairments in glutamatergic synaptic transmission in the hippocampus [71]. A genomewide association study of ADHD patients has also implicated alterations in Kalirin expression in ADHD [33]. Dendritic pathology and decreased dendritic spine density are prominent phenomena in early cases of Alzheimer's Disease, which correlate significantly with the progressive decline of mental faculties [72–75]. Alzheimer's Disease patients also show a significant decrease in Kalirin mRNA and protein expression in the hippocampus without significant changes in other brain regions [28]. This decrease in Kalirin expression has been associated with increased iNOS activity both in hippocampus from Alzheimer's patients and in cultured neuroblastoma cells [27]. These data lead to the hypothesis that lack of Kalirin is associated with the dendritic alterations and substantial decrease in spine density observed in Alzheimer's Disease.

Table 1.

Kalirin and human diseases.

| Kalirin isoform | Disease | Physiological relevance | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kalirin-7 (Duo) | Schizophrenia | Decreased spine density, decreased Kalirin-7 mRNA levels in the prefrontal cortex | [24] |

| Kalirin (unknown isoforms) | Schizophrenia | Kalirin mRNA increases 2-fold in the prefrontal cortex | [25] |

| Kalirin-7 | Schizophrenia | DISC1 regulates spine formation via Kal7-Rac1 | [10] |

| Kalirin | Schizophrenia | Kalirin is a risk factor for schizophrenia | [26] |

| Kalirin-7 | Alzheimer's Disease | Decreased levels of Kalirin-7 mRNA and protein in hippocampus | [27, 28] |

| Kalirin (unknown isoforms) | Animal model of depression | Decreased Kalirin expression in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus. ECT increases Kalirin expression in hippocampus | [29, 30] |

| Kalirin-7 | Animal model of depression | Decreased Kalirin-7 expression in hippocampus | [31] |

| Kalirin (unknown isoforms) | Animal model of epilepsy | Decreased Kalirin expression in hippocampus | [32] |

| Kalirin (unknown isoforms) | ADHD | Unknown | [33] |

| Kalirin (unknown isoforms) | Stroke | Unknown | [34, 35] |

| Kalirin (unknown isoforms) | Coronary Heart disease | Unknown | [36] |

| Kalirin (unknown isoforms) | Huntington's disease | Spectrin-like domains of Kalirin interact with HAP1 | [12] |

| Kalirin-7 | Animal model of cocaine addiction | An essential determinant of dendritic spine formation following cocaine treatment | [37, 38] |

The cause underlying major depression and the neurobiological basis of antidepressant therapy are not clear. Altered synaptic plasticity may play a key role in the pathogenesis and treatment of depression [76]. Major depression is associated with spine reductions in the hippocampus [77]. Kalirin expression and spine density in the hippocampus are decreased in the animal models of depression [29, 31, 78]. Kalirin levels and spine density in the hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons increase after repeated electroconvulsive treatment (ECT) [30, 79], one of the most effective therapies for depression [80, 81]. These observations suggest a role for Kalirin in the development of depression. In epileptic patients and in experimental models of epilepsy, there is a marked spine loss, abnormal spine shape, and alteration in dendritic morphology in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons [82, 83]. Animal models of epilepsy show a marked increase in Kalirin expression in the hippocampus [32], suggesting a role for Kalirin in the neuropathology of human epilepsy. Kalirin interacts with Huntingtin-associated protein 1 (HAP1) [12] and HAP1 dysfunction could contribute to the selective neuropathology in Huntingtin's disease [84]. Huntingtin's disease is characterized by loss of medium-sized spiny neurons in the striatum [85], alterations in spine density, and abnormalities in the size and shape of dendritic spines in striatal MSNs [86–88]. Overexpression of Kalirin-7 caused an increase in spine density while reduced expression of Kalirin-7 resulted in loss of dendritic spines and a decrease in dendritic complexity in the MSNs of striatal slice cultures which mimic in vivo conditions (Ma et al., unpublished). These data raise the possibility that Kalirin-7 may play a role in the neuropathology of Huntington's disease [87]. Finally, Kalirn-7 plays an important role in estrogen-mediated spine/synapse formation in the hippocampus [31, 40]. Regulation of Kalirin-7 by estrogen suggests a role for Kalirin in ovarian hormone-associated cognitive function and menopause-associated disorders [89–91]. Taken together, altered dendritic spine morphology and spine density remain the hallmarks of many human neurological and psychiatric disorders. There is a correlation between the levels of Kalirin expression and the pathology of dendritic spines in some psychiatric and neurological disorders. It is important to understand whether Kalirin is a trigger or one of many factors mediating the dendritic spine pathology of these diseases, which may be rescued by altering Kalirin expression/function or targeting downstream signals of Kalirin.

10. Conclusion/Future Studies

Kalirin-7, the major isoform of Kalirin in the adult brain, plays a critical role in spine formation/synaptic plasticity. Estrogen-mediated spine formation in hippocampal neurons and cocaine-induced increases in spine density in striatal MSNs require Kalirin-7. Kalirin has also been implicated in many neuropsychiatric and neurological diseases. Future studies will focus on investigating the underlying molecular mechanisms of Kalirin-7-mediated spine formation/synaptic plasticity and its role in neuropsychiatric and neurological diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants DK32948, DA22876, MH086552, DA032973 from NIH and 11SCA28 from Connecticut Innovations. Thanks are due to Drs. Dick Mains and Betty Eipper for their comments.

References

- 1.Rashidul Alam M, Caldwell BD, Johnson RG, Darlington DN, Mains RE, Eipper BA. Novel proteins that interact with the COOH-terminal cytosolic routing determinants of an integral membrane peptide-processing enzyme. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(45):28636–28640. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.45.28636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alam MR, Johnson RC, Darlington DN, Hand TA, Mains RE, Eipper BA. Kalirin, a cytosolic protein with spectrin-like and GDP/GTP exchange factor-like domains that interacts with peptidylglycine α-amidating monooxygenase, an integral membrane peptide-processing enzyme. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(19):12667–12675. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.19.12667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rossman KL, Der CJ, Sondek J. GEF means go: turning on Rho GTPases with guanine nucleotide-exchange factors. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2005;6(2):167–180. doi: 10.1038/nrm1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Negishi M, Katoh H. Rho family GTPases and dendrite plasticity. Neuroscientist. 2005;11(3):187–191. doi: 10.1177/1073858404268768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tolias KF, Duman JG, Um K. Control of synapse development and plasticity by Rho GTPase regulatory proteins. Progress in Neurobiology. 2011;94(2):133–148. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Penzes P, Woolfrey KM, Srivastava DP. Epac2-mediated dendritic spine remodeling: implications for disease. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience. 2011;46(2):368–380. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson RC, Penzes P, Eipper BA, Mains RE. Isoforms of Kalirin, a neuronal Dbl family member, generated through use of different 5′- and 3′-ends along with an internal translational initiation site. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(25):19324–19333. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000676200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McPherson CE, Eipper BA, Mains RE. Genomic organization and differential expression of Kalirin isoforms. Gene. 2002;284(1-2):41–51. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)00386-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McPherson CE, Eipper BA, Mains RE. Kalirin expression is regulated by multiple promoters. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience. 2004;22(1-2):51–62. doi: 10.1385/JMN:22:1-2:51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayashi-Takagi A, Takaki M, Graziane N, et al. Disrupted-in-Schizophrenia 1 (DISC1) regulates spines of the glutamate synapse via Rac1. Nature Neuroscience. 2010;13(3):327–332. doi: 10.1038/nn.2487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ratovitski EA, Alam MR, Quick RA, et al. Kalirin inhibition of inducible nitric-oxide synthase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274(2):993–999. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.2.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colomer V, Engelender S, Sharp AM, et al. Huntingtin-associated protein 1 (HAP1) binds to a Trio-like polypeptide, with a rac1 guanine nucleotide exchange factor domain. Human Molecular Genetics. 1997;6(9):1519–1525. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.9.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koo TH, Eipper BA, Donaldson JG. Arf6 recruits the Rac GEF Kalirin to the plasma membrane facilitating Rac activation. BMC Cell Biology. 2007;8, article no. 29 doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-8-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabiner CA, Mains RE, Eipper BA. Kalirin: a dual Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor that is so much more than the sum of its many parts. Neuroscientist. 2005;11(2):148–160. doi: 10.1177/1073858404271250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xin X, Rabiner CA, Mains RE, Eipper BA. Kalirin12 interacts with dynamin. BMC Neuroscience. 2009;10, article no. 61 doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-10-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Penzes P, Johnson RC, Kambampati V, Mains RE, Eipper BA. Distinct roles for the two Rho GDP/GTP exchange factor domains of Kalirin in regulation of neurite growth and neuronal morphology. Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21(21):8426–8434. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-21-08426.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schiller MR, Blangy A, Huang J, Mains RE, Eipper BA. Induction of lamellipodia by Kalirin does not require its guanine nucleotide exchange factor activity. Experimental Cell Research. 2005;307(2):402–417. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawai T, Sanjo H, Akira S. Duet is a novel serine/threonine kinase with Dbl-Homology (DH) and Pleckstrin-Homology (PH) domains. Gene. 1999;227(2):249–255. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00605-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma XM, Wang Y, Ferraro F, Mains RE, Eipper BA. Kalirin-7 is an essential component of both shaft and spine excitatory synapses in hippocampal interneurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28(3):711–724. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5283-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hansel DE, Quiñones ME, Ronnett GV, Eipper BA. Kalirin, a GDP/GTP exchange factor of the Dbl family, is localized to nerve, muscle, and endocrine tissue during embryonic rat development. Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry. 2001;49(7):833–844. doi: 10.1177/002215540104900704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferraro F, Ma XM, Sobota JA, Eipper BA, Mains RE. Kalirin/Trio Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factors regulate a novel step in secretory granule maturation. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2007;18(12):4813–4825. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-05-0503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma XM, Huang J, Wang Y, Eipper BA, Mains RE. Kalirin, a multifunctional rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor, is necessary for maintenance of hippocampal pyramidal neuron dendrites and dendritic spines. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23(33):10593–10603. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-33-10593.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muller D, Buchs PA, Stoppini L. Time course of synaptic development in hippocampal organotypic cultures. Developmental Brain Research. 1993;71(1):93–100. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(93)90109-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hill JJ, Hashimoto T, Lewis DA. Molecular mechanisms contributing to dendritic spine alterations in the prefrontal cortex of subjects with schizophrenia. Molecular Psychiatry. 2006;11(6):557–566. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Narayan S, Tang B, Head SR, et al. Molecular profiles of schizophrenia in the CNS at different stages of illness. Brain Research. 2008;1239:235–248. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kushima I, Nakamura Y, Aleksic B, et al. Resequencing and association analysis of the KALRN and EPHB1 genes and their contribution to Schizophrenia susceptibility. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq118. Schizophrenia Bulletin. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Youn H, Ji I, Ji HP, Markesbery WR, Ji TH. Under-expression of Kalirin-7 increases iNOS activity in cultured cells and correlates to elevated iNOS activity in Alzheimer’s disease hippocampus. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2007;12(3):271–281. doi: 10.3233/jad-2007-12309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Youn H, Jeoung M, Koo Y, et al. Kalirin is under-expressed in Alzheimer’s disease hippocampus. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2007;11(3):385–397. doi: 10.3233/jad-2007-11314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alttoa A, Kõiv K, Hinsley TA, Brass A, Harro J. Differential gene expression in a rat model of depression based on persistent differences in exploratory activity. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;20(5):288–300. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma XM, Mains RE, Eipper BA. Plasticity in hippocampal peptidergic systems induced by repeated electroconvulsive shock. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27(1):55–71. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00284-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li W, Li QJ, An SC. Preventive effect of estrogen on depression-like behavior induced by chronic restraint stress. Neuroscience Bulletin. 2010;26(2):140–146. doi: 10.1007/s12264-010-0609-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharma AK, Searfoss GH, Reams RY, et al. Kainic acid-induced f-344 rat model of Mesial temporal lobe epilepsy: gene expression and canonical Pathways. Toxicologic Pathology. 2009;37(6):776–789. doi: 10.1177/0192623309344202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lesch K-P, Timmesfeld N, Renner TJ, et al. Molecular genetics of adult ADHD: converging evidence from genome-wide association and extended pedigree linkage studies. Journal of Neural Transmission. 2008;115(11):1573–1585. doi: 10.1007/s00702-008-0119-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berȩsewicz M, Kowalczyk JE, Zabłocka B. Kalirin-7, a protein enriched in postsynaptic density, is involved in ischemic signal transduction. Neurochemical Research. 2008;33(9):1789–1794. doi: 10.1007/s11064-008-9631-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krug T, Manso H, Gouveia L, et al. Kalirin: a novel genetic risk factor for ischemic stroke. Human Genetics. 2010;127(5):513–523. doi: 10.1007/s00439-010-0790-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang L, Hauser ER, Shah SH, et al. Peakwide mapping on chromosome 3q13 identifies the kalirin gene as a novel candidate gene for coronary artery disease. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2007;80(4):650–663. doi: 10.1086/512981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mains RE, Kiraly DD, Eipper-Mains JE, Ma X, Eipper BA. Kalrn promoter usage and isoform expression respond to chronic cocaine exposure. BMC Neuroscience. 2011;12, article 20 doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-12-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kiraly DD, Ma XM, Mazzone CM, Xin X, Mains RE, Eipper BA. Behavioral and morphological responses to cocaine require Kalirin7. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;68(3):249–255. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Penzes P, Johnson RC, Sattler R, et al. The neuronal Rho-GEF Kalirin-7 interacts with PDZ domain-containing proteins and regulates dendritic morphogenesis. Neuron. 2001;29(1):229–242. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00193-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ma X-M, Huang J-P, Kim E-J, et al. Kalirin-7, an important component of excitatory synapses, is regulated by estradiol in hippocampal neurons. Hippocampus. 2011;21(6):661–677. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kiraly DD, Lemtiri-Chlieh F, Levine ES, Mains RE, Eipper BA. Kalirin binds the NR2B subunit of the NMDA receptor, altering its synaptic localization and function. Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31(35):12554–12565. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3143-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xie Z, Srivastava DP, Photowala H, et al. Kalirin-7 controls activity-dependent structural and functional plasticity of dendritic spines. Neuron. 2007;56(4):640–656. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xin X, Wang Y, Ma XM, et al. Regulation of Kalirin by Cdk5. Journal of Cell Science. 2008;121(15):2601–2611. doi: 10.1242/jcs.016089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cahill ME, Jones KA, Rafalovich I, et al. Control of interneuron dendritic growth through NRG1/erbB4-mediated kalirin-7 disinhibition. Molecular Psychiatry. 2012;17(1):99–107. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kiraly DD, Stone KL, Colangelo CM, et al. Identification of kalirin-7 as a potential post-synaptic density signaling hub. Journal of Proteome Research. 2011;10(6):2828–2841. doi: 10.1021/pr200088w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ma XM, Johnson RC, Mains RE, Eipper BA. Expression of Kalirin, a neuronal GDP/GTP exchange factor of the trio family, in the central nervous system of the adult rat. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2001;429(3):388–402. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20010115)429:3<388::aid-cne3>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fremeau RT, Troyer MD, Pahner I, et al. The expression of vesicular glutamate transporters defines two classes of excitatory synapse. Neuron. 2001;31(2):247–260. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00344-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fremeau RT, Kam K, Qureshi Y, et al. Vesicular glutamate transporters 1 and 2 target to functionally distinct synaptic release sites. Science. 2004;304(5678):1815–1819. doi: 10.1126/science.1097468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maccaferri G, Lacaille JC. Interneuron Diversity series: hippocampal interneuron classifications—making things as simple as possible, not simpler. Trends in Neurosciences. 2003;26(10):564–571. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Benes FM, Berretta S. GABAergic interneurons: implications for understanding schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25(1):1–27. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00225-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Powell EM, Campbell DB, Stanwood GD, Davis C, Noebels JL, Levitt P. Genetic disruption of cortical interneuron development causes region- and GABA cell type-specific deficits, epilepsy, and behavioral dysfunction. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23(2):622–631. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-02-00622.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lewis DA, Hashimoto T, Volk DW. Cortical inhibitory neurons and schizophrenia. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2005;6(4):312–324. doi: 10.1038/nrn1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ramos B, Baglietto-Vargas D, Rio JCD, et al. Early neuropathology of somatostatin/NPY GABAergic cells in the hippocampus of a PS1 × APP transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of Aging. 2006;27(11):1658–1672. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ma XM, Kiraly DD, Gaier ED, et al. Kalirin-7 is required for synaptic structure and function. Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28(47):12368–12382. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4269-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cahill ME, Xie Z, Day M, et al. Kalirin regulates cortical spine morphogenesis and disease-related behavioral phenotypes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(31):13058–13063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904636106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lai KO, Ip NY. Recent advances in understanding the roles of Cdk5 in synaptic plasticity. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2009;1792(8):741–745. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Akashi K, Kakizaki T, Kamiya H, et al. NMDA receptor GluN2B (GluRε2/NR2B) subunit is crucial for channel function, postsynaptic macromolecular organization, and actin cytoskeleton at hippocampal CA3 synapses. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29(35):10869–10882. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5531-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brigman JL, Wright T, Talani G, et al. Loss of GluN2B-containing NMD A receptors in CA1 hippocampus and cortex impairs long-term depression, reduces dendritic spine density, and disrupts learning. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30(13):4590–4600. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0640-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ohno T, Maeda H, Murabe N, et al. Specific involvement of postsynaptic GluN2B-containing NMDA receptors in the developmental elimination of corticospinal synapses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(34):15252–15257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906551107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gambrill AC, Barria A. NMDA receptor subunit composition controls synaptogenesis and synapse stabilization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(14):5855–5860. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012676108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xie Z, Cahill ME, Radulovic J, et al. Hippocampal phenotypes in kalirin-deficient mice. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience. 2011;46(1):45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Martínez-Raga J, Knecht C, Cepeda S. Modafinil: a useful medication for cocaine addiction? Review of the evidence from neuropharmacological, experimental and clinical studies. Current drug abuse reviews. 2008;1(2):213–221. doi: 10.2174/1874473710801020213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Smith MJ, Thirthalli J, Abdallah AB, Murray RM, Cottler LB. Prevalence of psychotic symptoms in substance users: a comparison across substances. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2009;50(3):245–250. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Majewska MD. Cocaine addiction as a neurological disorder: implications for treatment. NIDA research monograph. 1996;163:1–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mendelson JH, Mello NK. Drug therapy: management of cocaine abuse and dependence. New England Journal of Medicine. 1996;334(15):965–972. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199604113341507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Büttner A. Review: the neuropathology of drug abuse. Neuropathology and Applied Neurobiology. 2011;37(2):118–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2010.01131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kiraly DD, Ma XM, Mazzone CM, Xin X, Mains RE, Eipper BA. Behavioral and morphological responses to cocaine require Kalirin7. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;68(3):249–255. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Millar JK, Christie S, Porteous DJ. Yeast two-hybrid screens implicate DISC1 in brain development and function. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2003;311(4):1019–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.10.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bradshaw NJ, Porteous DJ. DISC1-binding proteins in neural development, signalling and schizophrenia. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62(3):1230–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Berlanga ML, Price DL, Phung BS, et al. Multiscale imaging characterization of dopamine transporter knockout mice reveals regional alterations in spine density of medium spiny neurons. Brain Research. 2011;1390:41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jensen V, Rinholm JE, Johansen TJ, et al. N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor subunit dysfunction at hippocampal glutamatergic synapses in an animal model of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuroscience. 2009;158(1):353–364. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tackenberg C, Ghori A, Brandt R. Thin, stubby or mushroom: spine pathology in alzheimer’s disease. Current Alzheimer Research. 2009;6(3):261–268. doi: 10.2174/156720509788486554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Baloyannis SJ. Dendritic pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2009;283(1-2):153–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.02.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mavroudis IA, Fotiou DF, Manani MG, et al. Dendritic pathology and spinal loss in the visual cortex in Alzheimer's disease: a Golgi study in pathology. International Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;121(7):347–354. doi: 10.3109/00207454.2011.553753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Perez-Cruz C, Nolte MW, Van Gaalen MM, et al. Reduced spine density in specific regions of CA1 pyramidal neurons in two transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31(10):3926–3934. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6142-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.von Bohlen und Halbach O. Structure and function of dendritic spines within the hippocampus. Annals of Anatomy. 2009;191(6):518–531. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Law AJ, Weickert CS, Hyde TM, Kleinman JE, Harrison PJ. Reduced spinophilin but not microtubule-associated protein 2 expression in the hippocampal formation in schizophrenia and mood disorders: molecular evidence for a pathology of dendritic spines. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161(10):1848–1855. doi: 10.1176/ajp.161.10.1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Norrholm SD, Ouimet CC. Altered dendritic spine density in animal models of depression and in response to antidepressant treatment. Synapse. 2001;42(3):151–163. doi: 10.1002/syn.10006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chen F, Madsen TM, Wegener G, Nyengaard JR. Repeated electroconvulsive seizures increase the total number of synapses in adult male rat hippocampus. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;19(5):329–338. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fink M. Convulsive therapy: a review of the first 55 years. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2001;63(1–3):1–15. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00367-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McClintock SM, Brandon AR, Husain MM, Jarrett RB. A systematic review of the combined use of electroconvulsive therapy and psychotherapy for depression. The Journal of ECT. 2011;27:236–243. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0b013e3181faaeca. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fiala JC, Spacek J, Harris KM. Dendritic spine pathology: cause or consequence of neurological disorders? Brain Research Reviews. 2002;39(1):29–54. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(02)00158-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sgobio C, Ghiglieri V, Costa C, et al. Hippocampal synaptic plasticity, memory, and epilepsy: effects of long-term valproic acid treatment. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;67(6):567–574. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wu LLY, Zhou XF. Huntingtin associated protein 1 and its functions. Cell Adhesion and Migration. 2009;3(1):71–76. doi: 10.4161/cam.3.1.7511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Vonsattel J-P, Myers RH, Stevens TJ. Neuropathological classification of Huntington's disease. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 1985;44(6):559–577. doi: 10.1097/00005072-198511000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Graveland GA, Williams RS, DiFiglia M. Evidence for degenerative and regenerative changes in neostriatal spiny neurons in Huntington’s disease. Science. 1985;227(4688):770–773. doi: 10.1126/science.3155875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ferrante RJ, Kowall NW, Richardson EP. Proliferative and degenerative changes in striatal spiny neurons in Huntington’s disease: a combined study using the section-Golgi method and calbindin D28k immunocytochemistry. Journal of Neuroscience. 1991;11(12):3877–3887. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-12-03877.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Spires TL, Grote HE, Garry S, et al. Dendritic spine pathology and deficits in experience-dependent dendritic plasticity in R6/1 Huntington’s disease transgenic mice. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;19(10):2799–2807. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816X.2004.03374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Boulware MI, Kent BA, Frick KM. The impact of age-related ovarian hormone loss on cognitive and neural function. doi: 10.1007/7854_2011_122. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Scott E, Zhang Q-G, Wang R, Vadlamudi R, Brann D. Estrogen neuroprotection and the critical period hypothesis. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 2012;33(1):85–104. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Riecher-Rössler A, Kulkarni J. Estrogens and gonadal function in schizophrenia and related psychoses. Current topics in behavioral neurosciences. 2011;8:155–171. doi: 10.1007/7854_2010_100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]