Abstract

Ionotropic glutamate receptors assemble as homo- or heterotetramers. One well-studied heteromeric complex is formed by the kainate receptor subunits GluK2 and GluK5. Retention motifs prevent trafficking of GluK5 homomers to the plasma membrane, but co-assembly with GluK2 yields functional heteromeric receptors. Additional control over GluK2/GluK5 assembly seems to be exerted by the amino-terminal domains, which preferentially assemble into heterodimers as isolated domains. However, the stoichiometry of the full-length GluK2/GluK5 heteromeric receptor has yet to be determined, as is the case for all non-NMDA glutamate receptors. Here we address this question using a single-molecule imaging technique that enables direct counting of the number of each GluK subunit type in homomeric and heteromeric receptors in the plasma membranes of live cells. We show that GluK2 and GluK5 assemble with 2:2 stoichiometry. This is an important step towards understanding the assembly mechanism, architecture and functional consequences of heteromer formation in ionotropic glutamate receptors.

Introduction

Ionotropic glutamate receptors (iGluRs) are key mediators of excitatory synaptic transmission In mammals they consist of 18 family members in three families: AMPA, kainate and NMDA receptors, which have distinct pharmacology, integrate distinct co-stimuli, generate unique currents and have different physiological function (Dingledine et al., 1999; Traynelis et al., 2010). Their diversity is further increased by RNA splicing and editing, co-assembly into receptors of mixed subunit composition, and association with several classes of auxiliary proteins, enabling them to perform a wide range of functions at pre-, post- and extra-synaptic sites (Gereau and Swanson, 2008).

There is a general consensus that all iGluRs assemble as tetramers. While NMDA receptors are obligatory heterotetramers consisting of two glycine- and two glutamate-binding subunits, non-NMDA iGluRs can be formed either by identical or related subunits, although heteromeric assemblies are more common in vivo. Kainate receptor subunits GluK1 (GluR5), GluK2 (GluR6) and GluK3 (GluR7) form functional homomeric receptors, as well as heteromers with one another (Cui and Mayer, 1999). In contrast, the two “high-affinity” subunits of this family, GluK4 (KA1) and GluK5 (KA2), require co-assembly with GluK1, GluK2 or GluK3 (Herb et al., 1992; Jaskolski et al., 2005).

One of the best-studied heteromers is the complex between GluK2 and GluK5. GluK2 expression in heterologous cells gives functional homomeric receptors, whereas GluK5 alone is retained in the endoplasmatic reticulum (ER) (Gallyas et al., 2003; Hayes et al., 2003; Ma-Högemeier et al., 2010; Ren et al., 2003). Co-expression of GluK5 with GluK2 yields heteromeric GluK2/GluK5 complexes on the cell surface with pharmacological (Herb et al., 1992; Swanson et al., 2002) and functional properties (Barberis et al., 2008; Garcia et al., 1998; Mott et al., 2003; Swanson et al., 2002) distinct from GluK2 homomers. GluK5 is widely expressed in the central nervous system (Herb et al., 1992; Wisden and Seeburg, 1993), and GluK2 is its prevalent interaction partner (Petralia et al., 1994; Wenthold et al., 1994). Accordingly, mice lacking GluK2 show a strongly decreased expression of GluK5 (Ball et al., 2010; Christensen et al., 2004; Nasu-Nishimura et al., 2006). If both high affinity subunits, GluK4 and GluK5, are missing, kainate receptors do not longer contribute to EPSCs at mossy fiber synapses (Fernandes et al., 2009).

While the GluK2a isoform harbors a forward trafficking motif (Yan et al., 2004), several cytoplasmatic ER retention/retrieval motifs and an endocytotic motif have been identified in GluK5 (Gallyas et al., 2003; Hayes et al., 2003; Nasu-Nishimura et al., 2006; Ren et al., 2003; Vivithanaporn et al., 2006). Membrane trafficking of GluK5 is only observed in complexes with other subunits like GluK2, which shield or over-ride these motifs. Impairment of the GluK5 motifs yields surface expression of GluK5, but these complexes are non-functional (Hayes et al., 2003; Nasu-Nishimura et al., 2006; Ren et al., 2003). Similar mechanisms regulate the trafficking and assembly of other GluK2 isoforms (Coussen et al., 2005), and of other heteromeric complexes (Jaskolski et al., 2005).

Importantly, the finding of intracellular ER retention/retrieval motifs on GluK5, which are overcome upon assembly with a GluK2 subunit, does not answer the question, whether heteromeric complexes assemble with a defined stoichiometry. This mechanism prevents trafficking of GluK5 homotetramers and, one would expect, also of complexes with three GluK5 subunits, where one GluK5 subunit cannot over-ride the retention motifs, but tetrameric complexes incorporating either one or two GluK5 subunits should be able to reach the cell surface.

Another important factor, which might determine the subunit stoichiometry of GluK2/GluK5 heteromers, is the amino-terminal domain (ATD) of these subunits, which determine the assembly into the distinct families (Ayalon and Stern-Bach, 2001), and whose dimerization is thought to initiate receptor biogenesis (Greger et al., 2007). The recent wealth of structural and thermodynamic data on the isolated ATDs of GluK2 and GluK5 revealed a strong preference for heterodimerization, while homodimerization of GluK2 ATDs was weaker, and of GluK5 ATDs weaker still, leading to a proposal for how 2:2 heteromeric complexes might form (Hansen and Traynelis, 2011; Kumar et al., 2011).

The exact subunit composition of heteromeric receptors at the cell surface, however, is an important, but still missing piece for understanding the assembly, architecture and function of non-NMDA iGluRs, which is difficult to deduce from functional experiments. Here we set out to determine the exact subunit stoichiometry of heteromeric GluK2/GluK5 receptors using a single-molecule subunit counting technique based on photobleaching of fluorescently labeled fusion proteins. This approach enabled us to study the composition of heterogeneous receptor populations on the surface of living cells.

Results

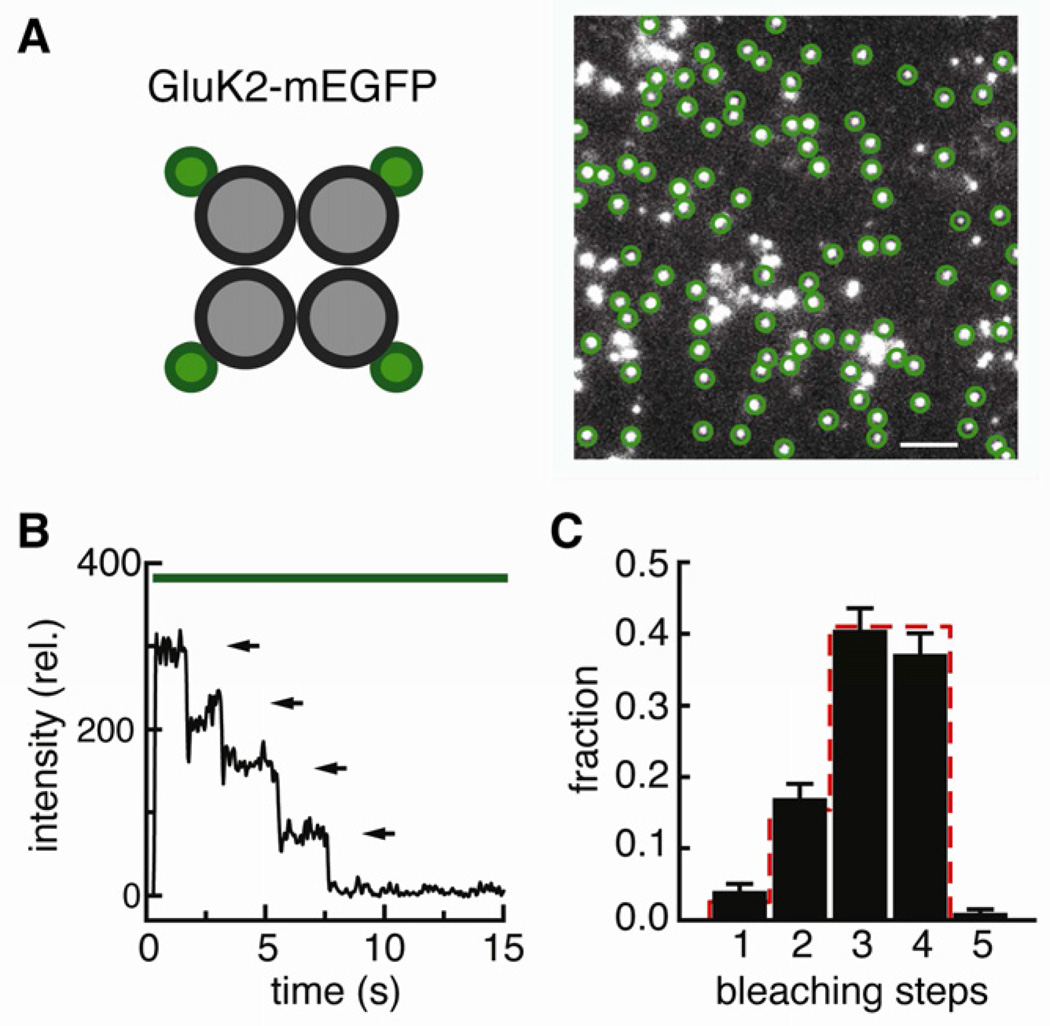

As a first step to investigate the molecular composition of GluK2/GluK5 complexes, we performed single molecule subunit counting experiments (Ulbrich and Isacoff, 2007) on homomeric GluK2 receptors. Upon fusion of mEGFP to the C-terminus of GluK2 (GluK2-mEGFP) and low density expression in Xenopus oocytes we observed sparse, well-resolved and stationary spots of green fluorescence on the cell surface using TIRF microscopy (Figure 1A). The photobleaching of a single GFP is a discrete process; thus the fluorescence intensity of a protein complex with one or several GFP molecules drops in a stepwise fashion, and the number of steps reflects the number of GFP-tagged subunits in the complex. Fluorescence intensity trajectories (e.g. Figure 1B) show that the majority of the GluK2-mEGFP spots bleached in three or four steps, with smaller numbers at one and two steps (Figure 1C, black bars). This distribution of one, two, three and four bleaching steps originates from the fact that not all subunits contain a fluorescent mEGFP. The distribution observed for GluK2-mEGFP agrees well with the binominal distribution expected for a tetramer, based on a probability of p=0.80 for an individual mEGFP to be fluorescent (Figure 1C, red dashes). Similar values have been obtained on a variety of other membrane proteins (Tombola et al., 2008; Ulbrich and Isacoff, 2007, 2008; Yu et al., 2009), and this value was used to predict distributions throughout this study. The bright fluorescence and immobility of the spots, along with the close agreement between the experimental results and the theoretical prediction, demonstrate that the method enables the investigation of the subunit composition of GluK2 containing receptors at the surface of living cells with high accuracy, and confirms that GluK2 forms homotetrameric receptors.

Figure 1. GluK2 homotetramers.

(A) mEGFP was fused to the C-terminus of GluK2, expressed in Xenopus oocytes and imaged by TIRF spectroscopy. Circles mark single, stationary receptors that satisfy the criteria for analysis. Scale bar: 2 µm. (B) Fluorescence intensity trace of a representative spot bleaching in four steps indicated by arrows. (C) Number of bleaching steps observed for a total of 438 spots. The error bars represent the counting uncertainty. The red line gives the binominal distribution expected for a tetramer, based on a probability of 0.80 for an individual mEGFP to be fluorescent.

Next, we asked whether GluK5 alone can be detected at the cell surface. In contrast to GluK2-mEGFP, injection of RNA encoding GluK5-mEGFP did not yield bright fluorescent spots as typical for mEGFP-constructs located at the cell surface. Only diffuse dim fluorescence was observed, confirming GluK5-mEGFP expression, and consistent with the expectation that the subunit is retained intracellularly.

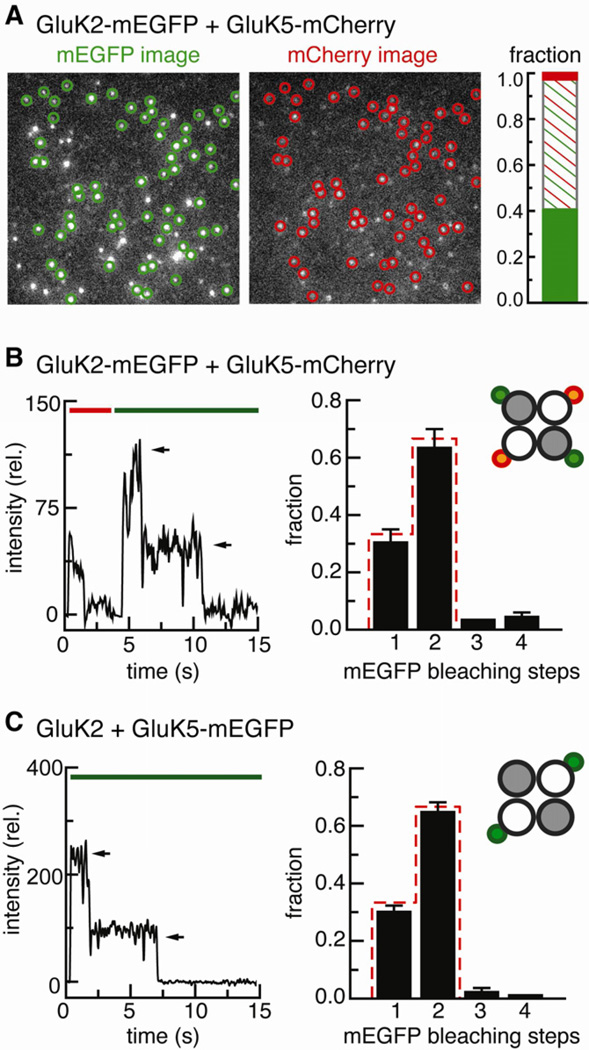

The distribution of GluK5 changed when it was co-expressed with GluK2. When GluK2-mEGFP was co-expressed with GluK5-mCherry at an RNA ratio of 1:3 many bright, clearly resolved and immobile red fluorescent spots from GluK5-mCherry were observed (Figure 2A, right image), which co-localized with green fluorescent spots of GluK2-mEGFP (Figure 2A, left image). Indeed, almost all of the red fluorescent spots (95.3 %, 341/358) also showed green fluorescence from GluK2-mEGFP. In contrast, a sizable fraction (41.4 %, 241/582) of the green fluorescent GluK2-mEGFP spots lacked a red-fluorescent GluK5-mCherry subunit. The results suggest that the cell membrane contained two populations of receptors: GluK2 homotetramers and GluK2/GluK5 heterotetramers. The small fraction of GluK5-mCherry for which no co-localization with GluK2-mEGFP was observed (4.7 %, 17/358) is fully accounted for by the number of complexes we predict to contain two subunits of each type, of which, based on a 0.8 probability of fluorescence, 4.0 % harbor two silent mEGFP molecules. This close agreement between observation and prediction is consistent with an absence of homomeric GluK5 complexes.

Figure 2. Co-expression of GluK2-mEGFP and GluK5-mCherry.

(A) Images from a representative movie. The circles indicate stationary spots that were observed in both the green mEGFP and the red mCherry channel. The bar graph shows the fractions of green-only, colocalizing and red-only spots for a total of 599 spots. (B) The co-expression experiment with GluK2-mEGFP and GluK5-mCherry allows to count the bleaching step distribution of GluK2 subunits colocalizing with GluK5. Left: One example trace with two mEGFP bleaching steps is shown. Right: Bleaching step analysis of 124 colocalizing spots. The red line gives the binominal distribution expected for two subunits with a probability of 0.80 for a single mEGFP to be fluorescent. The error bars represent the counting uncertainty. (C) Experiment with GluK2 and GluK5-mEGFP, which allows to count the number of GluK5 subunits per complex. Left: One example trace is shown. Right: The number of bleaching steps from 932 receptors agrees well with the binominal distribution expected for two subunits (red line, probability of 0.80 for a single mEGFP to be fluorescent).

Thus, this single molecule co-localization experiment supports earlier evidence that co-expression with GluK2 brings GluK5 to the surface, and that excess GluK2 subunits form homomeric complexes (Barberis et al., 2008; Ma-Högemeier et al., 2010). Importantly, the results also suggest a 2:2 stoichiometry in the GluK2/GluK5 heteromeric receptor.

To test rigorously the exact subunit composition of GluK2/GluK5 heteromeric receptors, we counted bleaching steps of GluK2-mEGFP in spots where GluK5-mCherry was co-localized (Figure 2B). The majority of red/green spots gave one or two mEGFP bleaching steps (Figure 2B, black bars), with a distribution closely following the prediction for a complex with two GluK2-mEGFP molecules (Figure 2B, red dashes), consistent with each heteromeric receptor containing two GluK2 subunits and two GluK5 subunits. The small number of spots with three and four green bleaching steps (7.3%, 9/124) that co-localized with red GluK5-mCherry is consistent with the predicted occurrence of two or more receptor complexes located within in one diffraction-limited spot. On average, ~280 green and red-green fluorescent signals were observed in movies from these experiments, corresponding to a spot density of 6.8 % (see Experimental Procedures). This density, in first approximation, equals the probability for random co-localization.

To further test the interpretation that GluK2/GluK5 heteromers have a defined 2:2 stoichiometry, we tagged the GluK5 subunit with EGFP and counted how many GluK5 subunits are found in complex with unlabeled GluK2. Since GluK5 homomers are not trafficked to the surface, co-injection of GluK5-mEGFP and unlabeled GluK2 was expected to only give fluorescence from heteromeric receptors. In the cells expressing the unlabeled GluK2, GluK5-mEGFP gave bright, immobile fluorescent spots. The majority of fluorescent spots bleached in one or two steps (Figure 2C, black bars), agreeing with the prediction for complexes consisting of two labeled GluK5 subunits and two unlabeled GluK2 subunits. The small fraction of spots with three and four bleaching steps (4.3%, 40/932) is consistent with the predicted occurrence of two or more receptor complexes located within in one diffraction-limited spot at the density of spots that was employed (4.9%, 200 spots/movie).

In summary, the results show that surface expressed GluK2/GluK5 receptors have a predominant, if not exclusive, 2:2 stoichiometry.

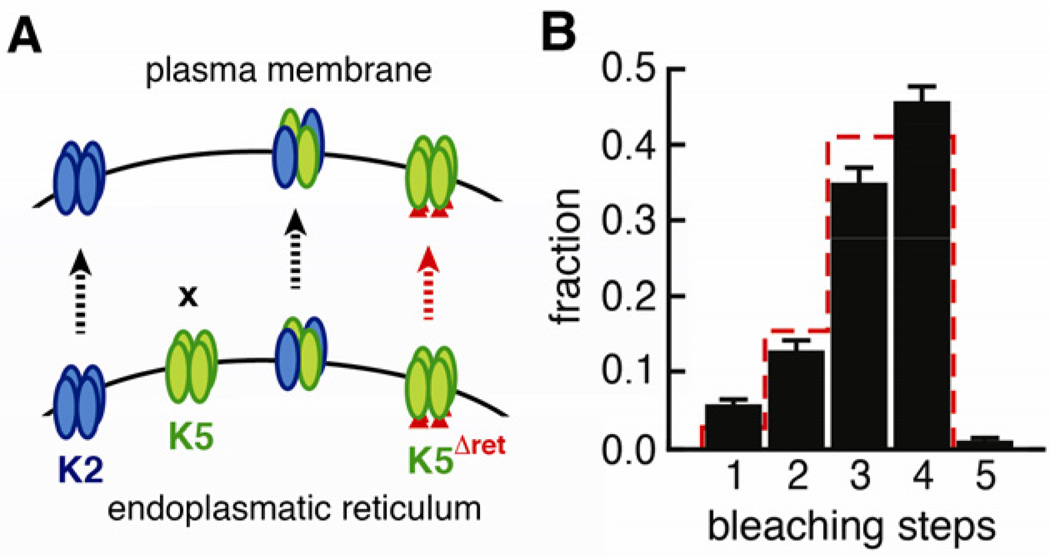

Previous experiments suggested that mutation of intracellular ER retention motifs regions promotes surface expression of GluK5 and that this receptor is homomeric (Hayes et al., 2003; Nasu-Nishimura et al., 2006; Ren et al., 2003; Vivithanaporn et al., 2006). These “released” GluK5 receptors are non-functional, but it is not known why. Transplanting the pore sequence of GluK5 into the background of GluK2 gives small currents, suggesting that GluK5 itself could be permeation competent (Villmann et al., 2008). Furthermore, it is known that GluK5 subunits harbor a functional ligand binding domain, with high affinity for both kainate and glutamate (Barberis et al., 2008; Herb et al., 1992). One explanation for the lack of currents from GluK5 homomers could be that GluK5 subunits do not assemble into the correct tetrameric architecture. Indeed, in vitro experiments have shown that the ATDs of GluK5 have an unusually low tendency to form homodimers, and that key contacts involved in tetramer formation are missing (Kumar and Mayer; Kumar et al., 2011). To check the assembly status of GluK5 homomers we generated GluK5ΔERret-mEGFP with mutations rendering the two ER retention motifs and the endocytotic di-Leu motif inactive (Figure 3A), as described previously (Nasu-Nishimura et al., 2006).

Figure 3. Homomeric GluK5 receptors.

(A) GluK2 forms homotetramers and traffics to the plasma membrane, whereas GluK5 is retained in the ER. Co-expression of GluK2 and GluK5 gives heterotetramers with 2:2 stoichiometry (see Figure 2). Impairment of the ER retention motifs on GluK5 (GluK5ΔERret) restores surface-expression, but these assemblies are non-functional. (B) Bleaching step analysis of GluK5ΔERret-mEGFP based on 658 spots. The red line gives the binominal distribution expected for four subunits with a probability of 0.80 for a single mEGFP to be fluorescent. In this experiment the maturation probability might be closer to 0.83. The error bars represent the counting uncertainty.

In contrast to wild type GluK5-mEGFP, expression of GluK5ΔERret-mEGFP gave bright immobile spots of green fluorescence at the cell surface. Bleaching analysis revealed mainly three and four bleaching steps per spot, consistent with assembly into homotetramers (Figure 3B). This demonstrates that, while heteromers are tightly regulated to contain two GluK2 and two GluK5 subunits, both GluK2 and GluK5 are intrinsically able to form tetramers. It also shows that a low stability of the ATD dimers and tetramers does not per se preclude tetramerization and trafficking. Our experiments, however, give no information, about whether the GluK5 homotetramers are fully and correctly assembled.

Discussion

The trafficking and function of GluK2/GluK5, one of the predominant kainate receptor complexes in the mammalian brain have been investigated in numerous studies. Here we focused on the assembly stoichiometry of these receptors employing a single-molecule imaging and subunit-counting technique. In agreement with previous work (Ball et al., 2010; Gallyas et al., 2003; Hayes et al., 2003; Herb et al., 1992; Ma-Högemeier et al., 2010; Nasu-Nishimura et al., 2006; Ren et al., 2003; Swanson et al., 1998; Vivithanaporn et al., 2006), we find that GluK2 assembles into homotetramers that readily traffic to the surface. Co-expression of GluK5 with GluK2 overcomes GluK5 retention and gives rise to GluK2/GluK5 heterotetramers with a subunit stoichiometry of 2:2. Removal of the GluK5 retention signals releases GluK5 homotetramers to the cell surface.

The data obtained by imaging GluK5-mEGFP co-assembled with untagged GluK2 (Figure 2C) allows us to rule out other stoichiometries. Based on chi-squared tests, the observed bleaching step distribution is significantly different from distributions expected for an equal mixture of 3:1, 2:2 and 1:3 GluK2/GluK5 complexes (p<0.0001), or an equal mixture of 3:1 and 2:2 complexes (p<0.0001). For random co-assembly of receptors from a pool of 50 % GluK2 homodimers and 50 % GluK2-GluK5 heterodimers, we would expect a mix of GluK2 homotetramers (25%), 3:1 GluK2/GluK5 tetramers (50%), and 2:2 GluK2/GluK5 tetramers (25 %), which is even less likely. Even a population as small as 2.5 % of 3:1 next to 2:2 GluK2/GluK5 complexes is not consistent with our data (p=0.030).

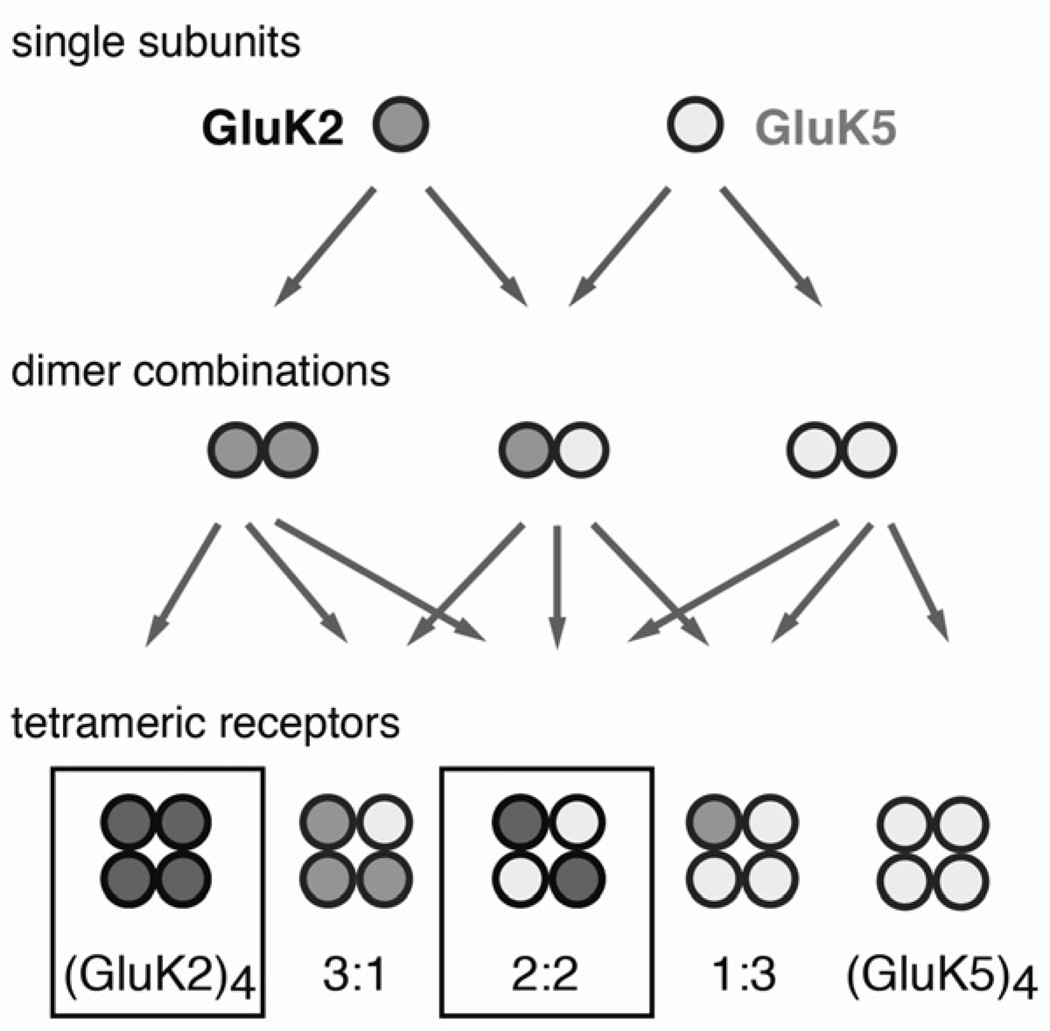

Although a 2:2 stoichiometry has been conjectured, direct evidence was lacking. Ionotropic glutamate receptors are classically described to be dimers of dimers, but what role dimeric intermediates play during assembly remains to be established (Figure 4). So far, two mechanisms that contribute to the assembly of GluK2 and GluK5 into heteromeric complexes have been characterized: i) intracellular trafficking motifs that retain GluK5 inside the cell and ii) the strong preferential assembly of the GluK2-GluK5 ATDs into heterodimers.

Figure 4. Possible stoichiometries for the assembly of GluK2 and GluK5.

The dimeric states are hypothetical. We only observe surface expression of (GluK2)4 homotetramers along with 2:2 GluK2/GluK5 heteromers. The drawing of the tetrameric assemblies does not denote the actual topology of the complexes.

Our data confirms that the presence of ER retention/retrieval motifs in GluK5 prevents trafficking of this subunit, and shows that co-assembly with GluK2 overcomes these signals (Hayes et al., 2003; Nasu-Nishimura et al., 2006; Ren et al., 2003; Vivithanaporn et al., 2006). The formation of complexes with 2:2 stoichiometry, in which the intracellular domain of each GluK2 covers retention signals from one GluK5, is consistent with this mechanism. Furthermore, we do not observe complexes with one GluK2 and three GluK5s, consistent with the expectation that all retention signals from three GluK5s cannot be covered by a single GluK2 subunit. However, we would expect to observe complexes with a GluK2/GluK5 stoichiometry of 3:1, since a single retention signal should get masked by one of the three GluK2s. The exclusive observation of a 2:2 stoichiometry therefore points to additional constraints for the assembly of GluK2/GluK5 complexes. In this context, it is interesting to note, that a preferential 2:2 stoichiometry was also suggested for the AMPA receptor complex GluA1/GluA2, where trafficking of neither subunit is suppressed (Mansour et al., 2001).

A second, important determinant for the assembly of GluK2/GluK5 appears to be in the association of the ATDs, which also direct the assembly of AMPA and kainate-type subunits into distinct receptor complexes (Ayalon and Stern-Bach, 2001). Isolated ATDs form several subunits have been shown to form highly stable dimers in solution (Karakas et al., 2011; Kumar et al., 2009; Kumar et al., 2011), suggesting that they play a role in early stages of assembly. A wealth of information comes from a recent study on the structural and energetic aspects of GluK2 and GluK5 ATD assembly (Kumar et al., 2011). In particular GluK2/GluK5 ATD heterodimers were found to be thermodynamically favored over both GluK2 homodimers and GluK5 homodimers (Kumar et al., 2011). At equal expression levels this strong preferential assembly of GluK2-GluK5 heterodimers over homodimers directly explains a 2:2 stoichiometry, since all subunits would engage in stable heterodimers. If GluK2 subunits are in excess, stable GluK2 homodimers are expected to form next to GluK2/GluK5 heterodimers. Incorporation of these homodimers could give rise to complexes with a GluK2/GluK5 stoichiometry of 3:1 as well as to complexes with a 2:2 stoichiometry and GluK2 homotetramers. Co-existence of GluK2 homomers and GluK2/GluK5 heteromers has been seen in functional studies (Barberis et al., 2008) as well as by fluorescence imaging (Ma-Högemeier et al., 2010). Our co-localization experiment is consistent with such a simultaneous presence of homo- and heterotetramers, and in addition shows that heteromers have a defined 2:2 stoichiometry. Thus, while the ATDs clearly contribute, they cannot on their own account for the assembly of full-length iGluRs. A similar conclusion was obtained in a study with chimeras of AMPA and kainate receptors, which suggested that dimer formation might be mediated by the ATDs, but that assembly into full-length receptors also depends on C-terminal regions (Ayalon and Stern-Bach, 2001). Along these lines, our experiments with a trafficking competent GluK5 variant (GluK5ΔERret) show that, that even GluK5 robustly assembles into homotetramers, although the GluK5 ATDs have only a weak tendency to form dimers in solution (Kumar et al., 2011).

In summary, assembly of the physiologically important GluK2/GluK5 complex seems to be tightly regulated with the assembly being confined to a 2:2 subunit stoichiometry. Retention motifs in GluK5 and the preferential assembly of the GluK2 and GluK5 ATD dimers as well as additional mechanisms appear to work together to control the assembly of this complex. Whether dimeric intermediates play a role in assembly remains to be established, especially since the only crystal structure of a glutamate receptor that includes the membrane spanning domain shows an interwound structure that is not adequately described as being a simple dimer of dimers (Sobolevsky et al., 2009). Particularly for heteromeric receptors, like GluK2/GluK5, it will be interesting to see the architecture of the full-length complexes, to elucidate how the determinants of assembly combine to define stoichiometry, and to determine whether subunit identity or position in the tetramer determine contributions to gating. The GluK2/GluK5 example of a non-NMDA glutamate receptor shown to have a defined subunit stoichiometry opens up new possibilities to address these questions.

Experimental Procedures

DNA Constructs and Expression in Xenopus Oocytes

Rat GluK2a(Q) (K.M. Partin, Colorado State University) and GluK5 (P. Seeburg, MPI Heidelberg; and K.W. Roche, NIH Bethesda) genes were cloned into pGEMHE, and constructs with C-terminal fusions of monomeric enhanced GFP (mEGFP) or monomeric Cherry (mCherry) were prepared (see Extended Experimental Procedures, SI). GluK2 subunits with C-terminal EGFP fusions have been shown to form functional homomeric receptors, as well as to interact with GluK5-EGFP to form functional heteromeric receptors (Ma-Högemeier et al., 2010). RNA transcripts were prepared from linearized DNA and injected into Xenopus laevis oocytes (50 nl of 0.05–0.20 µg/µl RNA).

Single-Molecule Imaging and Bleaching Step Analysis

Imaging of individual receptors and fluorescence bleaching was performed after 20–48 h expression at 18 °C, using a previously described total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy setup (Ulbrich and Isacoff, 2007; Yu et al., 2009). Briefly, oocytes were manually devitellinized and imaged with an Olympus ×100, NA 1.65 oil immersion objective through high refractive index coverslips (n= 1.78) in ND-96 at 20 °C. For details see Extended Experimental Procedures, SI. Only single, stationary, and diffraction-limited spots were included for analysis, and the number of bleaching steps was manually determined using software developed in house (Ulbrich and Isacoff, 2007). Regions of clustered or not-fully diffraction limited spots were excluded, as well as spots that moved, showed extreme intensity fluctuations or unequal bleaching steps. The bleaching step histograms present pooled data, taken form at least three different batches of oocytes. The error bars give the statistical uncertainty for a counting experiment, which is , for n being the number of counts. The expected binominal distributions of bleaching steps observed for two and four labeled subunits were calculated with a fixed probability of p=0.80 for mEGFP to be fluorescent (Ulbrich and Isacoff, 2007). Pearson’s chi-squared test was used to asses, whether the experimentally observed distributions can be explained by bleaching-step distributions calculated for different assembly stoichiometries.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Josh Levitz, Mark Mayer and Yael Stern-Bach for discussion, and we are grateful to Kathryn Partin, Katherine Roche, and Peter Seeburg for the gift of clones. This work was supported by grants to E.Y.I. from the National Institutes of Health (2PN2EY018241 and U24NS057631) and the Human Frontier Science Program (RGP0013/2010) as well as a postdoctoral fellowship to A.R. from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG RE 3101/1-1).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ayalon G, Stern-Bach Y. Functional assembly of AMPA and kainate receptors is mediated by several discrete protein-protein interactions. Neuron. 2001;31:103–113. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00333-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball SM, Atlason PT, Shittu-Balogun OO, Molnar E. Assembly and intracellular distribution of kainate receptors is determined by RNA editing and subunit composition. J Neurochem. 2010;114:1805–1818. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barberis A, Sachidhanandam S, Mulle C. GluR6/KA2 kainate receptors mediate slow-deactivating currents. J Neurosci. 2008;28:6402–6406. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1204-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen JK, Paternain AV, Selak S, Ahring PK, Lerma J. A mosaic of functional kainate receptors in hippocampal interneurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8986–8993. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2156-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coussen F, Perrais D, Jaskolski F, Sachidhanandam S, Normand E, Bockaert J, Marin P, Mulle C. Co-assembly of two GluR6 kainate receptor splice variants within a functional protein complex. Neuron. 2005;47:555–566. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui C, Mayer ML. Heteromeric kainate receptors formed by the coassembly of GluR5, GluR6, and GluR7. J Neurosci. 1999;19:8281–8891. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-19-08281.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingledine R, Borges K, Bowie D, Traynelis SF. The glutamate receptor ion channels. Pharmacol Rev. 1999;51:7–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes HB, Catches JS, Petralia RS, Copits BA, Xu J, Russell TA, Swanson GT, Contractor A. High-affinity kainate receptor subunits are necessary for ionotropic but not metabotropic signaling. Neuron. 2009;63:818–829. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallyas F, Jr., Ball SM, Molnar E. Assembly and cell surface expression of KA-2 subunit-containing kainate receptors. J Neurochem. 2003;86:1414–1427. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia EP, Mehta S, Blair LA, Wells DG, Shang J, Fukushima T, Fallon JR, Garner CC, Marshall J. SAP90 binds and clusters kainate receptors causing incomplete desensitization. Neuron. 1998;21:727–739. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80590-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gereau R, Swanson G. The glutamate receptors. Humana Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Greger IH, Ziff EB, Penn AC. Molecular determinants of AMPA receptor subunit assembly. Trends in Neurosci. 2007;30:407–416. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen KB, Traynelis SF. How glutamate receptor subunits mix and match: details uncovered. Neuron. 2011;71:198–200. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes DM, Braud S, Hurtado DE, McCallum J, Standley S, Isaac JT, Roche KW. Trafficking and surface expression of the glutamate receptor subunit, KA2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;310:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.08.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herb A, Burnashev N, Werner P, Sakmann B, Wisden W, Seeburg PH. The KA-2 subunit of excitatory amino acid receptors shows widespread expression in brain and forms ion channels with distantly related subunits. Neuron. 1992;8:775–785. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90098-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaskolski F, Coussen F, Mulle C. Subcellular localization and trafficking of kainate receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karakas E, Simorowski N, Furukawa H. Subunit arrangement and phenylethanolamine binding in GluN1/GluN2B NMDA receptors. Nature. 2011;475:249–253. doi: 10.1038/nature10180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar J, Mayer ML. Crystal structures of the glutamate receptor ion channel GluK3 and GluK5 amino-terminal domains. J Mol Biol. 404:680–696. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar J, Schuck P, Jin R, Mayer ML. The N-terminal domain of GluR6-subtype glutamate receptor ion channels. Nat Struc Mol Biol. 2009;16:631–638. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar J, Schuck P, Mayer ML. Structure and assembly mechanism for heteromeric kainate receptors. Neuron. 2011;71:319–331. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma-Högemeier ZL, Körber C, Werner M, Racine D, Muth-Köhne E, Tapken D, Hollmann M. Oligomerization in the endoplasmic reticulum and intracellular trafficking of kainate receptors are subunit-dependent but not editing-dependent. J Neurochem. 2010;113:1403–1415. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour M, Nagarajan N, Nehring RB, Clements JD, Rosenmund C. Heteromeric AMPA receptors assemble with a preferred subunit stoichiometry and spatial arrangement. Neuron. 2001;32:841–853. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00520-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott DD, Washburn MS, Zhang S, Dingledine RJ. Subunit-dependent modulation of kainate receptors by extracellular protons and polyamines. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1179–1188. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-04-01179.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasu-Nishimura Y, Hurtado D, Braud S, Tang TT, Isaac JT, Roche KW. Identification of an endoplasmic reticulum-retention motif in an intracellular loop of the kainate receptor subunit KA2. J Neurosci. 2006;26:7014–7021. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0573-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petralia RS, Wang YX, Wenthold RJ. Histological and ultrastructural localization of the kainate receptor subunits, KA2 and GluR6/7, in the rat nervous system using selective antipeptide antibodies. J Comp Neurol. 1994;349:85–110. doi: 10.1002/cne.903490107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren Z, Riley NJ, Garcia EP, Sanders JM, Swanson GT, Marshall J. Multiple trafficking signals regulate kainate receptor KA2 subunit surface expression. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6608–6616. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-16-06608.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobolevsky AI, Rosconi MP, Gouaux E. X-ray structure, symmetry and mechanism of an AMPA-subtype glutamate receptor. Nature. 2009;462:745–756. doi: 10.1038/nature08624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson GT, Green T, Heinemann SF. Kainate receptors exhibit differential sensitivities to (S)-5-iodowillardiine. Mol. Pharm. 1998;53:942–949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson GT, Green T, Sakai R, Contractor A, Che W, Kamiya H, Heinemann SF. Differential activation of individual subunits in heteromeric kainate receptors. Neuron. 2002;34:589–598. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00676-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tombola F, Ulbrich MH, Isacoff EY. The voltage-gated proton channel Hv1 has two pores, each controlled by one voltage sensor. Neuron. 2008;58:546–556. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traynelis SF, Wollmuth LP, McBain CJ, Menniti FS, Vance KM, Ogden KK, Hansen KB, Yuan H, Myers SJ, Dingledine R. Glutamate receptor ion channels: structure, regulation, and function. Pharmacol Rev. 2010;62:405–496. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.002451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulbrich MH, Isacoff EY. Subunit counting in membrane-bound proteins. Nat Methods. 2007;4:319–321. doi: 10.1038/NMETH1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulbrich MH, Isacoff EY. Rules of engagement for NMDA receptor subunits. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:14163–14168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802075105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villmann C, Hoffmann J, Werner M, Kott S, Strutz-Seebohm N, Nilsson T, Hollmann M. Different structural requirements for functional ion pore transplantation suggest different gating mechanisms of NMDA and kainate receptors. J. Neurochem. 2008;107:453–465. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivithanaporn P, Yan S, Swanson GT. Intracellular trafficking of KA2 kainate receptors mediated by interactions with coatomer protein complex I (COPI) and 14-3-3 chaperone systems. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:15475–15484. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512098200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenthold RJ, Trumpy VA, Zhu WS, Petralia RS. Biochemical and assembly properties of GluR6 and KA2, two members of the kainate receptor family, determined with subunit-specific antibodies. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:1332–1339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisden W, Seeburg PH. A complex mosaic of high-affinity kainate receptors in rat brain. J Neurosci. 1993;13:3582–3598. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-08-03582.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan S, Sanders JM, Xu J, Zhu Y, Contractor A, Swanson GT. A C-terminal determinant of GluR6 kainate receptor trafficking. J Neurosci. 2004;24:679–691. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4985-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Ulbrich MH, Li MH, Buraei Z, Chen XZ, Ong AC, Tong L, Isacoff EY, Yang J. Structural and molecular basis of the assembly of the TRPP2/PKD1 complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:11558–11563. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903684106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.