Abstract

Selectively fluorinated molecules are important as materials, pharmaceuticals, and agrochemicals, but their synthesis by simple, mild, laboratory methods is challenging. We report a straightforward method for the cross-coupling of a difluoromethyl group with readily available reagents to form difluoromethylarenes. The reaction of electron-neutral, electron-rich, and sterically hindered aryl and vinyl iodides with the combination of CuI, CsF and TMSCF2H leads to the formation of difluoromethylarenes in high yield with good functional group compatibility. This transformation is surprising, in part, because of the prior observation of the instability of CuCF2H.

The unique stability, reactivity and biological properties of fluorinated compounds contribute to their widespread use in many chemical disciplines. Compounds containing a trifluromethyl group have been studied extensively. Compounds containing partially fluorinated alkyl groups, such as a difluoromethyl group, should be similarly valuable for medicinal chemistry because such groups could act as lipophilic hydrogen bond donors and as bio-isosteres of alcohols and thiols.1,2 However, methods for the introduction of a difluoromethyl group are limited, and methods for the introduction of a difluoromethyl group onto arenes are even more limited. Hence there is a current need for new procedures to generate difluoromethylarenes.3

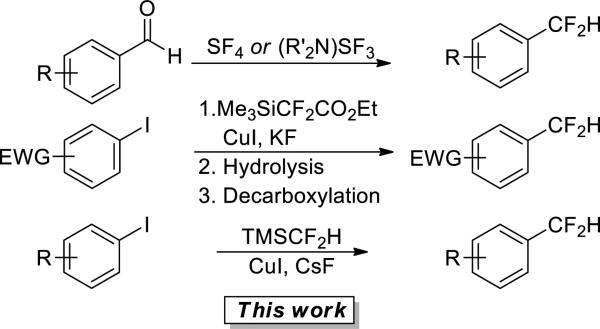

Most current syntheses of difluoromethylarenes require hazardous reagents or multi-step sequences (Scheme 1). Fluorodeoxygenation of aldehydes with sulfur tetrafluoride or amino-sulfurtrifluorides (DAST, Deoxofluor) is the most common route to difluoromethyl compounds. However, these reagents release hydrogen fluoride upon contact with water and may undergo explosive decomposition when heated.4 Amii and coworkers recently reported a three-step route to difluoromethylarenes; however, the final step of this process only occurred with electron-deficient aryl iodides, and the three-step process with electron-poor arenes occurred in modest overall yields (Scheme 1).5 Baran recently reported a new reagent that leads to the addition of difluoromethyl radicals to heteroaromatic systems under mild conditions.6 However, reactions with arenes were not reported. Thus, methods for the introduction of a difluoromethyl group onto arenes and methods for the introduction of the difluoromethyl group with regioselectivities that complement those resulting from radical-based reactions are needed.

Scheme 1.

Preparation of Difluoromethylarenes

In contrast to the recent success in developing copper mediated trifluoromethylation of aryl halides7 methods for related copper-mediated difluoromethylation of aryl halides have not been developed. Difluoromethyl copper complexes are much less stable than trifluoromethyl copper complexes and are known to be unstable toward the formation of tetrafluoroethane and cis-difluoroethylene.3,8 Despite this instability, we have identified conditions for copper-mediated difluoromethylation of aryl iodides. We report our results on this difluoromethylation process. The difluoromethylation reaction occurs with aryl iodides containing a wide range of functional groups, as well as vinyl iodides, in a single step with inexpensive and readily available reagents.

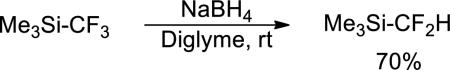

We chose to develop difluoromethylations with trimethylsilyl difloromethane (TMSCF2H) as the source of the CF2H group because fluoroalkylsilanes are accessible, commercially available, stable, and readily prepared on large scale. Most important for the current work, TMSCF2H is accessible on multi-gram scale, as shown in eq 1, by sodium borohydride reduction of the Ruppert-Prakash reagent (TMSCF3).9 Initial attempts to extend our previously published work on the trifluoromethylation of aryl iodides10 with (1,10-phenanthroline)CuCF3 to the difluoromethylation of aryl iodides with pre-formed or in-situ generated (1,10-phenanthroline)CuCF2H gave large amounts of arene. Only trace amounts of the difluoromethylarene product were formed. Reactions of 1-butyl-4-iodobenzene conducted with tertbutoxide or fluoride to activate the silane and a broad range of copper (I) sources and exogenous ligands gave similar product distibutions.

|

(1) |

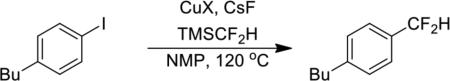

However, reactions conducted without added ligand resulted in high conversion to the difluoromethylarene. Various copper(I) sources were found to mediate the difluoromethylation of 1-butyl-4-iodobenzene, but reactions conducted with CuI provided higher yields than did those with CuBr, CuBr-SMe2, or CuCl (Table 1). Reactions conducted with cesium fluoride led to transfer of the difluoromethyl group from TMSCF2H without significant background decomposition of the silane. Studies with various ratios of reagents showed that reactions with 1 equiv of CuI, 3 equiv of CsF and 5 equiv of TMSCF2H occurred in reproducibly high yields. Reactions conducted with less CsF or TMSCF2H resulted in moderate to good yields (Table 1, entries 6-8). The excess TMSCF2H in the reaction likely converts CuCF2H to the cuprate, Cu(CF2H)2- (vide infra).

Table 1.

Effect of Copper Source and Reagent Ratios on the Difluoromethylation of 1-butyl-4-iodobenzenea

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | CuX (eq) | CsF (eq) | TMSCF2H (eq) | yield (%) |

| 1 | CuBr (1.0) | 2.0 | 5.0 | 84 |

| 2 | CuBr-SMe2 (1.0) | 2.0 | 5.0 | 70 |

| 3 | CuCI (1.0) | 2.0 | 5.0 | 53 |

| 4 | Cul (1.5) | 1.5 | 1.5 | 26 |

| 5 | Cul (3.0) | 3.0 | 3.0 | 36 |

| 6 | Cul (1.0) | 1.0 | 5.0 | 55 |

| 7 | Cul (1.0) | 2.0 | 5.0 | 91 |

| 8 | Cul (1.0) | 3.0 | 3.0 | 75 |

| 9 | Cul (1.0) | 3.0 | 5.0 | 100 |

Reactions were performed with 0.1 mmol of 1-butyl-4-iodobenzene in 0.5 mL of NMP for 24 hours. The yield was determined by 19F NMR with 1-bromo-4-fluorobenzene as an internal standard added after the reaction.

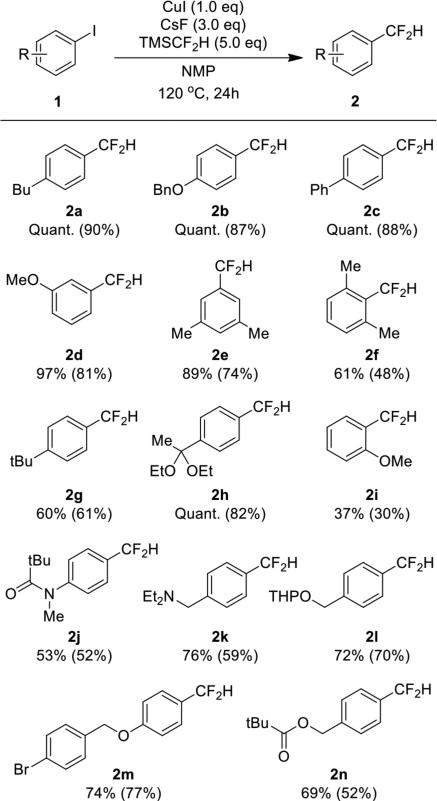

The reaction conditions developed for the difluoromethylation of 1-butyl-4-iodobenzene were suitable for the conversion of a range of aryl iodides 1 to difluoromethylarenes 2 (Table 2). Electron-neutral, electron-rich, and sterically hindered aryl iodides reacted in high yield. Amine, ether, amide, ester, aromatic bromide and protected alcohol functionality were tolerated under the standard reaction conditions. While ketones and aldehydes underwent competing direct addition of the difluoromethyl group,11 acetal-protected ketone 1h gave quantitative conversion to difluoromethylarene 2h. In contrast to reactions of electron-rich and electron-neutral aryl iodides, reactions of electron-deficient aryl iodides formed arene as the major product, along with trace amounts of trifluoromethyl and tetrafluoroethylarene. The latter products, presumably, form by a sequence similar to the one that forms pentafluoroethylarenes during copper-mediated trifluoromethylation of aryl halides involving difluorocarbene.7 The volatility of difluoromethylarenes and the similar polarity of the difluoromethylarene to side-products made the yields of isolated material lower than the yields determined by NMR spectroscopy in some cases..

Table 2.

Difluoromethylation of Aryl Iodides with TMSCF2H Mediated by Copper Iodidea

|

Reactions were performed with 0.1 mmol of aryl iodide to determine 19F NMR yields with 1-bromo-4-fluorobenzene as an internal standard added after the reaction. Isolated yields, shown in parenthesis, were obtained from reactions performed with 0.5 mmol of aryl iodide.

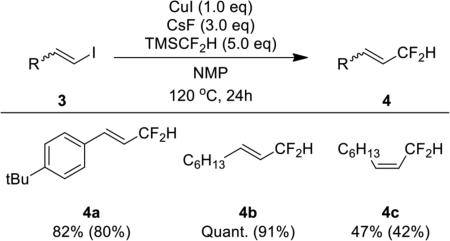

This difluoromethylation protocol was also suitable for the difluoromethylation of vinyl iodides 3 to prepare allylic difluorinated alkenes 4 (Table 3). This family of products has been prepared by the reaction of sulfur tetrafluoride or aminosulfurtrifluorides and α-ß unsaturated aldehydes; however formation of products from allylic substitution and rearrangements of reaction intermediates occur in these systems, resulting in a mixture of isomers.4 In addition, the cross-coupling of vinyl iodides with TMSCF2H avoids the use of hazardous sulfurfluoride reagents and reactive, electrophilic α,ß-unsaturated aldehydes. Cis and trans alkenes, as well as styrenyl iodides, reacted in good yield to give a single stereoisomer of the coupled product.

Table 3.

Difluoromethylation of Vinyl Iodides with TMSCF2H Mediated by Copper Iodide.a

|

Reactions were performed with 0.1 mmol of vinyl iodide to determine 19F NMR yields with 1-bromo-4-fluorobenzene as an internal standard added after the reaction. Isolated yields, shown in parenthesis, were obtained from reactions with 0.5 mmol of vinyl iodide.

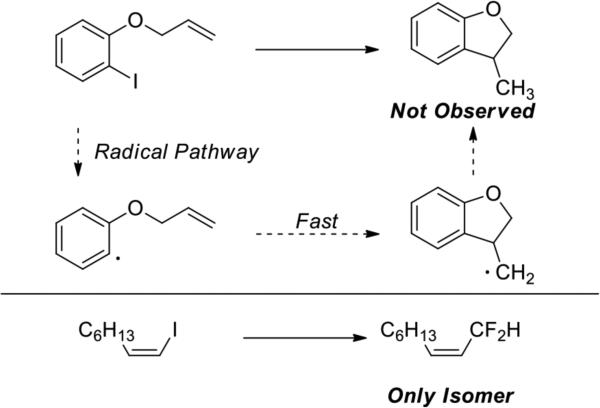

Reactions of aryl halides with Cu(I) species have been proposed in some cases to occur by radical intermediates12 and in other cases to occur through Cu(III) intermediates formed by oxidative addition of organic halides to a Cu(I) intermediate.13 Although the current evidence disfavors radical reactions of aryl halides with copper complexes containing neutral dative nitrogen ligands,14 the difluoromethylation in the current work occurs through complexes lacking such ligands and, therefore, could follow a different pathway. To probe the potential inter-mediacy of aryl radicals during this difluoromethylation reaction, we conducted the difluoromethylation of 1-(allyloxy)-2-iodobenzene (Scheme 2). The corresponding aryl radical undergoes 5-exo-trig cyclization with a rate constant of 1010 s-1 to form 3-methyl-2,3-dihydrobeznofuran after hydrogen atom abstraction from the solvent.15 Thus, if products from cyclization are not observed, then the reaction of the aryl radical with the fluoroalkyl species must occur with an effective first order rate constant of 1012 s-1 – 1013 s1, which approaches the time scale of a vibration and the diffusion-controlled limit. The reaction of 1-(allyloxy)-2-iodobenzene with CuI, CsF and TMSCF2H did not give any products resulting from cyclization. Instead, this reaction formed allyloxybenzene and the difluoromethylarene. Although the yield of difluoromethylarene was low (13%), in agreement with the result from the reaction of ortho iodoansole, this result argues against a mechanism involving an aryl radical intermediate.

Scheme 2.

Evidence against aryl and vinyl radical intermediates

Reactions of vinyl iodides also provide evidence against a radical intermediate. The difluoromethylation of Z-1-iodo-1-octene formed the difluoroallyl product with complete retention of the olefin geometry. Because of the configurational instability of vinyl radicals a mixture of stereoisomers of the coupled products would be expected to form if a vinyl radical were formed. Only one stereoisomer was observed (Scheme 2).

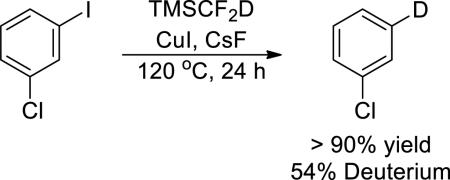

An unusual feature of the scope of this coupling process is the higher yields obtained from reactions of electron-rich aryl iodides than from reactions of electron-poor aryl iodides. Most often, electron-deficient electrophiles react faster and in higher yields than electron-rich electrophiles in cross-coupling reactions. To elucidate the origin of the effect of arene electronics on the yield of the difluoromethylation reaction, we conducted experiments with deuterium labeled TMSCF2D, prepared from TMSCF3 and NaBD4. The reaction of 1-chloro-3-iodobenzene with CuI, CsF and TMSCF2D resulted in greater than 50% deuterium incorporation at the iodide position of the arene product (eq 2). Thus, the arene product appears to form, at least in part, by an overall hydride transfer from trimethyl(difluoromethyl)silane.

|

(2) |

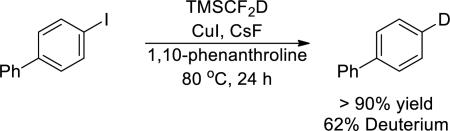

Similar results were obtained from reactions conducted with exogenous ligand. The reaction of 4-iodo-1,1'-biphenyl with TMSCF2D in the presence of CuI, CsF and 1,10-phenanthroline formed arene in greater than 90% yield, and the arene contained greater than 60% deuterium at the iodide position (eq 3). Reactions conducted in deuterated solvent did not lead to incorporation of deuterium into the arene, showing that the solvent is not a source of hydrogen for the hydrodehalogenation process.

|

(3) |

The observation of tetrafluoroethyl and trifluoromethyl side products from reactions of electron-deficient aryl iodides suggests that difluorocarbene may be formed under the reaction conditions (vide supra). However, reactions conducted with added cyclohexene or styrene to trap difluorocarbene gave only trace amounts or no detectable amount of products resulting from cyclopropanation, respectively.

Difluoromethylcopper(I) has been reported to undergo a combination of disproportionation and homo-coupling to form cis-difluoroethylene and 1,1,2,2-tetrafluoroethane, even below room temperature.8 If the reaction we report occurs through CuCF2H, the reaction of this complex with aryl iodide must be faster than decomposition. However, the reactions of aryl iodides with Cu(I) species typically require elevated temperatures, and electron-poor aryl iodides typically react with Cu(I) faster than electron-rich aryl iodides.16 Thus, we suggest that two different reaction pathways are likely to form the difluoromethylarene and the arene, and the rate of formation of arene would be faster with electron-poor arenes than with electron-rich arenes.

To assess the identity of the difluoromethyl copper species that could react with the aryl iodide, we combined CuI, CsF, and TMSCF2H and heated the mixture at 120 °C in the absence of aryl iodide. Within 5 min, this reaction formed a product with 19F NMR chemical shift and JH-F values (-116.6 ppm, J = 44 Hz) that matched those reported previously for the cuprate Cu(CF2H)2-.8,17, 18 This difluoromethylcuprate species in this difluoromethylation reaction is clearly more stable than the neutral CuCF2H.

Although speculative, we provide a rationalization of our ability to develop copper-mediated difluoromethylation, despite the instability of CuCF2H. We suggest that Cu(CF2H)2- acts as a stable reservoir for the neutral CuCF2H. Because prior studies have shown that two-coordinate cuprates react more slowly with haloarenes than do neutral complexes,14a-c we suggest that CuCF2H reacts with the haloarene. The low concentrations of CuCF2H should decrease the rate of bimolecular decomposition, relative to reaction with the haloarene. Future studies will assess these mechanistic hypotheses.

In summary, we have described a one-step procedure for the difluoromethylation of aryl and vinyl iodides that occurs with readily available and non-hazardous reagents. This reaction tolerates amine, ether, amide, ester, aromatic bromide and protected alcohol functionalities and occurs in high yield with sterically hindered aryl iodides. The simplicity and generality of this method makes it attractive for the introduction of a CF2H group into functionally diverse iodoarenes. Work is ongoing to develop conditions for difluormethylation of electron-poor aryl iodides, to develop reactions of heteroaryl iodides, and to develop reactions of higher difluoroalkyl groups.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank the NIH (GM-58108) for support of this work and Ramesh Giri for checking the procedure.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information.

Experimental procedures and characterization of all new compounds including 1H, 13C, and 19F NMR spectra.

REFERENCES

- 1.Erickson JA, McLoughlin JI. J. Org. Chem. 1995;60:1626. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meanwell NA. J. Med. Chem. 2011;54:2529. doi: 10.1021/jm1013693. and references therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu J, Zhang W, Wang F. Chem. Commun. 2009:7465. doi: 10.1039/b916463d. and references therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a Markovski LN, Pahinnik VE, Kirsanov AV. Synthesis. 1973:787. [Google Scholar]; b Middleton WJ. J. Org. Chem. 1975;40:574. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fujikawa K, Fujioka Y, Kobayashi A, Amii H. Org. Lett. 2011;13:5560. doi: 10.1021/ol202289z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fujiwara Y, Dixon JA, Rodriguez RA, Baxter RD, Dixon DD, Collins MR, Blackmond DG, Baran PS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:1494. doi: 10.1021/ja211422g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tomashenko OA, Grushin VV. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:4475. doi: 10.1021/cr1004293. and references therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a Eujen R, Hoge B, Brauer DJ. J. Organomet. Chem. 1996;519:7. [Google Scholar]; b Burton DJ, Hartgraves GA. J. Fluorine Chem. 2007;128:1198. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tyutyunov AA, Boyko VE, Igoumnov SM. Fluorine Notes. 2011;74:1. http://notes.fluorine1.ru/public/2011/1_2011/letters/letter2.html. For an alternative preparation of TMSCF2H: Prakash GKS, Hu J, Olah GA. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:4457. doi: 10.1021/jo030110z.

- 10.a Morimoto H, Tsubogo T, Litvinas ND, Hartwig JF. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:3793. doi: 10.1002/anie.201100633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Litvinas ND, Fier PS, Hartwig JF. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:536. doi: 10.1002/anie.201106668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao Y, Huang W, Zheng J, Hu J. Org. Lett. 2011;13:5342. doi: 10.1021/ol202208b.Prakash GKS, Hu J. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007;40:921. doi: 10.1021/ar700149s.Hagiwara T, Fuchikami T. Synlett. 1995:717. d See reference 3 for a more comprehensive overview of nucleophilic difluoromethylation.

- 12.a Paine AJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987;109:1496. [Google Scholar]; b Aalten HL, Vankoten G, Grove DM, Kuilman T, Piekstra OG, Hulshof LA, Sheldon RA. Tetrahedron. 1989;45:5565. [Google Scholar]; c Couture C, Paine AJ. Can. J. Chem. 1985;63:111. [Google Scholar]; d Arai S, Hida M, Yamagishi T. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1978;51:277. [Google Scholar]

- 13.a Weingarten H. J. Org. Chem. 1964;29:3624. [Google Scholar]; b Lindley J. Tetrahedron. 1984;40:1433. [Google Scholar]; c Zhang S-L, Liu L, Fu Y, Guo Q-X. Organometallics. 2007;26:4546. [Google Scholar]; d Cohen T, Cristea I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1976;98:748. [Google Scholar]; e Bethell DJ, Jenkins IL, Quan PM. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2. 1985:1789. [Google Scholar]

- 14.a Giri R, Hartwig JF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:15860. doi: 10.1021/ja105695s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Tye JW, Weng Z, Johns AM, Incarvito CD, Hartwig JF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:9971. doi: 10.1021/ja076668w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Tye JW, Weng Z, Giri R, Hartwig JF. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:2185. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Yu HZ, Jiang YY, Fu Y, Liu L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:18078. doi: 10.1021/ja104264v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Annunziata A, Galli C, Marinelli M, Pau T. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2001:1323. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strieter ER, Bhayana B, Buchwald SL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:78. doi: 10.1021/ja0781893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.For recent reviews of organocuprate chemistry see: Yoshikai N, Nakamura E. Chem. Rev. ASAP, dx.doi.org/10.1021/cr200241f.Nakamura E, Mori S. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000;39:3750. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20001103)39:21<3750::aid-anie3750>3.0.co;2-l.

- 18.A different 19F NMR signal was observed when CsF and TMSCF2H were allowed to react in the absence of CuI (-117.4 ppm, doublet, J = 52 Hz). We have tentatively assigned the structure of this difluoromethyl species to be the pentacoordinate-silicate, TMS(CF2H)2-, which is analogous to that of the silicate TMS(CF3)2- formed from TMSCF3 and fluoride. Maggiarosa N, Tyrra W, Naumann D, Kirij NV, Yagupolskii YL. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999;38:2252. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(19990802)38:15<2252::aid-anie2252>3.0.co;2-z.Kolomeitsev A, Bissky G, Lork E, Movchun V, Rusanov E, Kirsch P, Roschenthaler GV. Chem. Commun. 1999:1107.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.