Abstract

HIV- and AIDS-related stigma has been reported to be a major factor contributing to the spread of HIV. In this study, the authors explore the meaning of stigma and its impact on HIV and AIDS in South African families and health care centers. They conducted focus group and key informant interviews among African and Colored populations in Khayelitsha, Gugulethu, and Mitchell’s Plain in the Western Cape province. The audio-recorded interviews were transcribed and coded using NVivo. Using the PEN-3 cultural model, the authors analyzed results showing that participants’ shared experiences ranged from positive/nonstigmatizing, to existential/unique to the contexts, to negative/stigmatizing. Families and health care centers were found to have both positive nonstigmatizing values and negative stigmatizing characteristics in addressing HIV/AIDS-related stigma. The authors conclude that a culture-centered analysis, relative to identity, is central to understanding the nature and contexts of HIV/AIDS-related stigma in South Africa.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, stigma, culture, South Africa, PEN-3

That HIV/AIDS is a major health problem in South Africa is a fact. According to UNAIDS (2006), in South Africa an estimated 5.5 million people currently live with HIV/AIDS, of which 18.8% comprises adults age 15 to 49. In 2005, approximately 320,000 adults and children died of HIV/AIDS, while 1.2 million children lost their mothers, fathers, or both parents to HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS, 2006). Among South African youths age 15 to 24, a 2005 South African National HIV survey estimates that HIV incidence is 10.3%, and females in this age group have almost four times the HIV prevalence of males, at 16.9% versus 4.4% (Shisana et al., 2005). Furthermore, the national survey indicates that persons living in urban informal areas have the highest incidence of HIV at 7.0%, compared to rural informal areas at 2.0% and urban formal areas at 1.8% (Shisana et al., 2005).

In the Western Cape Province, a 2007 final report on major infectious diseases including HIV and tuberculosis estimated the current HIV infection prevalence rate of 15.7% (Draper, Pienaar, Parker, & Rehle, 2007). Findings from an annual antenatal HIV survey indicate that adults in the age group from 25 to 29 consistently account for the highest levels of HIV infection, with an estimated 20.1% of pregnant women in that age group being HIV positive (Draper et al., 2007).

Generally, the pandemic in South Africa places tremendous pressure on millions of families as the primary wage earners and/or caretakers fall sick, require care, and eventually die (Ardnt & Lewis, 2001). In the Western Cape, according to the 2000 Income and Expenditure Survey (Statistics South Africa, 2002), the average per capita income in 2000 was R21,344 ($2,753). With HIV/AIDS, breadwinners’ savings are consumed by health care and funeral costs (Desmond, Michael, & Gow, 2000; Fitzpatrick, McCay, & Smith, 2004). Furthermore, it is estimated that HIV is the fastest way for families to move from relative wealth to relative poverty (Rotheram-Borus, Flannery, Rice, & Lester, 2005). For example, in a study of 404 households affected by HIV/AIDS in South Africa, members of HIV/AIDS-affected households had incomes and expenditures that were independently (14%–26%) lower than those of unaffected households (Bachmann & Booysen, 2003). HIV/AIDS worsens poverty through loss of work time, income, and assets, which severely affects a household’s capacity to produce and purchase food (Fitzpatrick et al., 2004).

Studies indicate that there is a strong pervasive stigma attached to HIV/AIDS in South Africa (Campbell, Foulis, Maimane, & Sibiya, 2005; Groenewald, Nannan, Bourne, Laubscher, & Bradshaw, 2005; Kalichman & Simbayi, 2004). In the 2002 South Africa national survey, 26% of respondents reported that they would not be willing to share a meal with a person living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA), 18% were unwilling to sleep in the same room with someone with AIDS, and 6% would not talk to a person they knew who had AIDS (Shisana & Simbayi, 2002). Furthermore, the national survey conducted in 2005 indicates that stigma and discrimination against PLWHA are primary barriers to effective HIV prevention as well as to the provision of treatment, care, and support (Shisana et al., 2005). Kalichman and Simbayi (2003) suggest that AIDS-related stigma impedes efforts to promote voluntary counseling and testing and other HIV/AIDS prevention efforts. Furthermore, Campbell and colleagues (2005) suggest that among family members stigmatization is often cited as the most hurtful and damaging issue, deterring young people in particular from seeking HIV/AIDS-related counseling. Although AIDS stigma is recognized as a significant social issue in South Africa, few studies have attempted to explore in depth the role of culture in HIV-related stigma.

It is generally agreed that the sociological basis for understanding health-related stigma today has its origin in the work of Goffman (1963). Goffman examined the notion of alienation constructed in the form of individual deviance that results in what is considered to be a spoiled identity. For Harriet Deacon and her colleagues (Deacon, Stephney, & Prosalendis, 2005), stigma is an ideology that links a disease to a negative behavior in groups or society. Stigma is considered to be the result of fear and blame, rather than ignorance, and could be overcome with educational intervention. Thus, an understanding of stigma should begin with an understanding of the primary contexts within which these fears, blames, and behaviors are expressed.

Different aspects of HIV/AIDS stigmatization have been measured (Herek, Capitanio, & Widaman, 2002). For example, in a telephone survey that examined trends in stigma in the Unites States during the 1990s, Herek and colleagues found persistent discomfort with persons living with AIDS (PWAs), blame directed at PWAs for their condition, and misapprehensions about casual social contact with PWAs. In Nigeria, Alubo and colleagues (Alubo, Zwandor, Jolayemi, & Omudu, 2002) explored acceptance and stigmatization of PWAs in Southern Benue State. The authors found that level of stigmatization is high and acceptance of PWAs is low and that these reactions stem from the fear of contracting “a disease that has no cure,” believed to be transmissible through any form of physical contact.

In light of these measurements of stigma, which narrowly focus on the individual, Parker and Aggleton (2003) called for a broader understanding of stigma by examining questions of context and power as advanced by French philosopher Michel Foucault. For Foucault (see, e.g., The History of Sexuality, 1976/1978), power is central to constructing the dynamics of relationships between those who are privileged and those consigned to the margins of society. Such power differences further illuminate the depth and breadth of stigma that should be interrogated at levels beyond those of the individual. While Foucault’s work clearly highlights the relevance of power in understanding stigma, few attempts have been made to examine the issue of stigma within the question of African identity and issues of belonging. The questions of affirmation and belonging in the context of African identity are better anchored in the work of such luminary thinkers as Frantz Fanon and Cheikh Anta Diop, both of whom were vocal about the negative impact of apartheid on Black South African identity. In critiquing the racist apartheid policy of South Africa, Fanon (1967) indicated that “the problem of colonialism includes not only the interrelations of objective historical conditions but also human attitudes toward these conditions” (p. 84). A critical aspect of these historical conditions and human attitudes manifests in how well family experiences mirror the value and structure of the nation. In the case of South Africa, Fanon concluded that since families typically mirror the values, laws, and principles of a nation, oppressive regimes are bound to produce families whose experiences are normal only within each family but are alien in the outside world and even in their own nation. The disconnection between the experience in the family and conditions in the nation but outside the family are basically problems that colonialism imposed on African identity. For Diop (1991), the true question of identity is only skin deep since the differences on which oppression is based is phenotype—physical appearance—rather than genotype. According to Diop, “It would matter little that Botha and a Zulu have the same genotypic, i.e. the same genes in their chromosomes; this would have no influence on their daily lives since their external physical features are so different” (p. 124). These external features have been the focus of identity discourses from the apartheid era to the present day in which physical appearance continues to be used to classify South Africans even though such classification has been critiqued and rejected by many progressive South Africans. Thus, HIV and AIDS stigma cannot be examined without exploring the historical conditions that have privileged physical appearance in a society (see, e.g., Fassin & Schneider, 2003).

The present study examined the sociocultural and institutional contexts of stigma by focusing on the question of belonging and differences as expressions of identities. In a post-apartheid South Africa, the location of power along lines of racial, class, and gender identities is relevant with respect to group acceptance and rejection in relation to being advantaged and privileged as a racial group. This article focuses on South African cultural identities as a central component of efforts to eliminate HIV and AIDS stigma. While this article does not focus on African Americans, a parallel identity affirmation advanced by W. E. B. Du Bois is instructive. In his study of Philadelphia Negroes, Du Bois (1899/1996) was a visionary in challenging social scientists to understand the absolute conditions of African Americans rather than limiting their studies to comparative health status with Whites, as is common today in health disparity research (p. 148). In this study of stigma, we explore the absolute conditions of those South Africans who suffer the greatest burden of HIV and AIDS rather than focusing on how they compare to the White population. Furthermore, stigma as an expression of belonging and relationships conveys institutional and familial values that influence groups’ perceptions and interpretations of meanings and of acceptance and rejection as they relate to a disease such as HIV/AIDS. Thus, culture enables us to negotiate and develop strategies that could help us to understand the complex nature of stigma and ensure that appropriate interventions are developed for HIV reduction and possible elimination. Our main thesis is this: The question of stigma in Africa cannot be understood solely as a question of individual deviance or societal differences but more centrally as a question of affirmation of identity or the lack thereof. Thus, while the American (Goffman) and the French (Foucault) approaches offer important insights that should not be ignored, they do not represent the foundation on which the discourse on stigmatization of PLWHA in Africa should be based.

The research results presented in this article offer a perspective on stigma in South Africa that derives from the roles of families and health care institutions as contexts where individuals express their acceptance and/or rejection within the contexts of group agency. Thus, behaviors that are either supportive or rejecting of HIV-related stigma seem to be either supportive or rejecting of one’s group. Therefore, taking into consideration the sociocultural issues related to stigma, we sought to better understand the meaning of HIV and AIDS stigma in the South African family and health care settings by using the PEN-3 cultural model to frame the research questions and analysis of results.

THE PEN-3 MODEL

To offer a strategy for organizing and analyzing complex and interlocking spheres of cultural identity and health behavior, the PEN-3 cultural model was developed (Airhihenbuwa, 1989). This model was not developed to test different constructs of behavior but rather to examine cultural meanings such as languages and values of health behavior that have gained a central location in framing people’s relationships with health in social and cultural contexts. PEN-3 has been used to frame health-related projects ranging from specific diseases such as cancer (Abernethy et al., 2005; Erwin et al., 2007), hypertension (Walker, 2000), and diabetes (Goodman, Yoo, & Jack, 2006) to behaviors such as smoking (Beech & Scarinci, 2003; Scarinci, Silveira, Figueiredo dos Santos, & Beech, 2007) and food choices (James, 2004; Underwood et al., 1997) and recommendations for national strategies to eliminate health disparities among ethnic minorities for obesity (Kumanyika & Obarzanek, 2003). The model offers a cultural framework that provides (and in many cases obligates) researchers and interventionists to partner with communities when defining health problems and seeking solutions to those problems.

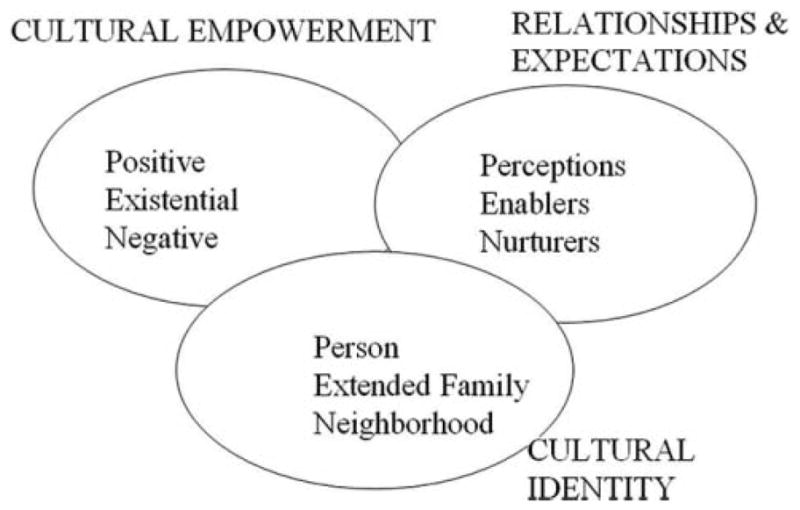

As seen in Figure 1, the model is made up of three interrelated and interdependent dimensions: cultural identity (CI), relationships and expectations (RE), and cultural empowerment (CE) (Airhihenbuwa, 2007a). In RE, we focus on three domains—perceptions (beliefs and values held by people about a condition), enablers (resources that either promote or hinder efforts at changing behavior), and nurturers (the role of friends and family in making positive or negative changes). In CE, we focus on three domains—positive (identifying positive attributes rather than focusing only on the negatives), existential (understanding the qualities that make the culture unique but that should not be blamed for program failure), and negative (values and behaviors that contribute to health problems). In CI, there are also three domains—person (focusing on the one person who may have the most impact on health decisions), extended family (the role of kinship in decisions that may affect one person), and neighborhood (the context of the community and values that shape health decisions). There are two phases in the application of PEN-3. They are the assessment phase and the intervention phase. In the assessment phase, the two dimensions (and their three domains) of RE and CE are crossed to generate nine cells. In the intervention phase, and based on the three domains of CI, researchers/interventionists go back to the community to share their findings and further learn from the community before deciding where to begin the intervention (point of entry). This community engagement is critical to the participatory method required in PEN-3.

Figure 1.

The PEN-3 Model

METHOD

The Pennsylvania State University (PSU) partnered with the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) in South Africa to develop a capacity-building project in which faculty and students at the University of the Western Cape (UWC) in Cape Town, South Africa, and the University of Limpopo (UL), Turfloop campus, in Sovenga, South Africa, were trained to use PEN-3 to frame the understanding of stigma in South Africa. The project’s central aim is to develop and strengthen research capacity for disadvantaged, underserved Black postgraduate students at UWC and UL. In the first two years of this study (2004 and 2005), we partnered with UWC, and we focused on three communities, two of them predominately Black African (Khayelitsha and Gugulethu) and one predominately Colored (Mitchell’s Plain).1 (For a conceptualization of Colored identities in Western Cape Province, see Erasmus & Pieterse, 1999.) This article is based on results from these three communities that were the focus of Years 1 and 2. In these communities, we collected data in four different settings: among members of the general public, among families of PLWHA, among PLWHA themselves, and among health care providers at local primary health care clinics.

SAMPLE

During the first two years in which we collaborated with UWC to study the communities identified above, we trained 12 South African postgraduate students (6 per year). Three UWC mentors were also recruited to mentor 2 students each per year for the two years of the program. Thus, the mentors remained for two years even though new students were recruited for each year. Seven of the 12 students were Black/African, and 5 were Colored (2 in Year 1 and 3 in Year 2). Only 3 students (2 in Year 1 and 1 in Year 2) of the 12 were men. Only 3 (2 were men) were working toward PhDs, while 9 students were enrolled in a master’s degree program. The three UWC mentors for the first two years of the project were professors of psychology, even though one of them (Tammy Shefer) directs the gender studies program at UWC. A total of 50 focus group (FG) and 59 key informant (KI) interviews were conducted among 453 (108 males and 345 females) participants in the three communities. Participants included PLWHA, family members of a PLWHA, health care workers, community leaders, and youths. Most FGs were conducted in the communities and among PLWHA, while individual interviews were mainly conducted with health care providers in health care facilities. The project is currently completing its fifth year, and data from the Limpopo province (2006 and 2007) will be presented in future publications.

Training of students

Each year (2004 and 2005) at the beginning of the fall semester, the mentors and other research partners from HSRC spent 7 to 10 days in the United States with the PSU research partners to develop the research plans for the proceeding year. Two months before this meeting, a campuswide announcement was made at UWC to advertise and begin the screening process for the six students to be selected for the next training cycle, which is January to November. All the applications were reviewed during the meeting in the United States, and final candidates were notified for an interview in Cape Town to select the 6 students. Research capacity-building training was conducted for 10 days during January of each year for the research team, which included the research investigators, the mentors, and the 6 students. During this workshop, we addressed current research on stigma in South Africa, including several studies conducted by our partner agency, HSRC. Each year, the POLICY Project, based in Pretoria, accepted our invitation to share its members’ experiences working on HIV/AIDS-related stigma activities. Another key organization that accepted our invitation to share similar experiences was the Treatment Action Campaign.

In the second year, we showed the South African movie Yesterday (a movie about a mother’s struggle to deal with the impact of HIV and AIDS on her family, community, and health care center) for the students, and we had our mentors, each of whom are also counselors, available for any questions or to help the students process any negative emotions that may have been stirred by watching the movie. One of the key requirements for applying to be a student in our project was a commitment to conduct research on HIV/AIDS-related stigma in South Africa. During the workshop, mentors worked with their students to generate the key questions for their studies. As a team, we worked with students to finalize their topics and generate the key items and scenarios for the year. We developed six key items and scenarios (with probes for each) for each student to use in his or her interview. Three of the items were the same for all FG and KI, two items were specific to each FG and KI research population, and the sixth item asked the student’s FG or KI for any additional items they wished to discuss. In this article, we focus only on the three items or scenarios that were posed to all FGs and KIs. The three items or scenarios were (a) What are your views about HIV and AIDS (probing for positive, unique, and negative factors that influence these views in the family and/or health care center)? (b) How would you say PLWHA are treated in your family and/or at the health center (with probes to elicit positive, unique, and negative views and also to know if women are treated differently)? (c) How has HIV/AIDS affected you as a family member or as a health care worker (probing for positive, unique, and negative views)?

To prepare the students for the FG interviews, they were first introduced to lessons in conducting interviews. They then participated in grouped and individualized role-play activities designed for this study and based on the investigators’ years of experience in conducting FG and KI interviews. Finally, the students were trained to use an electronic digital recorder for their interviews. The data from each interview were downloaded to a laptop computer following each interview, and a professional transcriber was hired to do the transcription. Following the transcription, each student verified the accuracy of the transcripts by comparing them with notes taken during the FG interview. During each interview, students moderated their FGs, and a second student served as an assistant moderator by taking notes and managing the recorder. The pairing was done among the students and their mentors. The format for recording interviews on a notepad was the same for each interview. At the end of each interview, the recorder was able to offer the FG a summary of what had been discussed to find out if there were key points not captured during the interview. For example, each key point was marked on the left margin of the notepad by an asterisk (*), each point for which clarification was needed was marked by a question mark (?), ideas and thoughts for which further clarification was needed were marked by a circle (○), and nonverbal communications were marked by a rectangle (□); these were discussed with the moderator at the end of the interview.

INSTRUMENT AND DATA COLLECTION

Two research instruments were developed by the research team, namely, an FG guide and a KI interview schedule. A central theme of both instruments was to locate HIV and AIDS in their historical and cultural contexts. We developed questions or scenarios and translated them into isi-Xhosa and Afrikaans. By design, our questions did not include the word stigma (see Airhihenbuwa, 2007b). We instead used terms like shame and rejection and attempted to ask more open-ended questions that would not predetermine responses. When the word stigma was used, it was only after it was introduced by one of the participants in the FG or KI interviews. Each of the 12 students (6 per year) was trained in FG and KI interviewing skills and selected one of the three communities in which data were collected. Informed consent was obtained from each participant in either a group and/or individual setting. Translators with years of experience at HSRC translated and back-translated the interview guides. The data were collected using the language preferred by the participants—either isi-Xhosa, English, or Afrikaans. Following each interview, data were stored in a laptop computer and sent to an independent transcriptionist. The final transcripts were later translated into English if the interviews were conducted in isi-Xhosa or Afrikaans. Permission was always sought to record the FG or KI interview sessions using a digital recorder. All digital files were stored in a laptop and secured in the office of the project director. Ethical approval was obtained from both the PSU Institutional Review Board and HSRC’s Research Ethics Committee.

DATA ANALYSIS

Following data collection, a weeklong training on the use of the NVivo 2.0 software package was conducted for students and their mentors in Cape Town. NVivo 2.0 is software used for organizing data generated from qualitative research. The training portion with NVivo was part of the capacity-building training objective of the project, which prepares each student to independently conduct his or her own project from inception to analysis with a final written report. Thus, each student conducted a preliminary independent analysis of his or her data to share with the research team. This is included in each student’s final report to the team. The principal investigator and his trained graduate students in the United States conducted the overall analysis and shared outcomes with the students in South Africa so that the members of the entire research team could learn from each other. We used this comparative analytic method to demonstrate the strength of international collaboration, showing a better understanding of the similarities and differences in the logic of generating themes by South African students who conducted the interviews as compared to non–South African graduate students in the United States who are part of the project. All students participated in every training workshop, and all were trained in NVivo. The comparison of the logic of generating themes between the South African and U.S.-based students has been a useful tool in training and retraining of students both in the United States and in South Africa.

Using the NVivo 2.0 software package, all transcripts were coded using both inductive and deductive methods. The initial codes were derived inductively from the qualitative data set. Three forms of coding (descriptive, topic, and analytical) were used (Creswell, 2003; Denzin & Lincoln, 2000). Descriptive coding involved the storing of information about participants’ gender, race, community, and language used in conducting the discussions. Topic coding involved organizing the material from text data or from paragraphs and sentence segments into groups and labeling them with a term, preferably from the actual language used by participants in the study (e.g., Z3 is a slang term used to describe a PLWHA). Analytical coding involved the creation of categories that expressed new ideas about the data by considering the meanings in context (e.g., food as a measure of acceptance or rejection). After all transcripts were coded, each analyst generated a code frequency table, indicating how often a particular code was used. Codes used fewer than five times were scrutinized to decide on fit and relevance. This process generated 33 themes initially, 20 themes subsequently, and 12 major themes finally. The 12 major themes are as follows:

HIV/AIDS and challenges to prevention;

context of care in clinics and hospitals;

gender and HIV/AIDS;

law, security, and protection;

food as a measure of acceptance and rejection;

knowledge and perception about HIV/AIDS;

cultural and racial identity;

HIV stigma and discrimination and impact on disclosure;

socioeconomic status and HIV;

positive and negative aspects of condom use;

youth and HIV/AIDS; and

parental involvement and HIV/AIDS.

However, for the purposes of this article, we generated 3 major themes that formed the three subheadings in the Result section. These 3 themes cut across the 12 themes identified above. The results presented are not comparative between demographics, such as males versus females, but rather represent common views expressed across the different FG and KI interviews.

Trustworthiness

One of the key requirements of PEN-3 is to go back to the community and report what was found in the study. This process proved to be one of the most rewarding experiences for the students. The community reports were conducted by one of the students who is also a coauthor on this article (Regina Dlakulu). Her contributions to the research proved to be exceptional, and as a result, she was hired by HSRC to become the community liaison for this and other related research projects. Her primary responsibility was to facilitate entry into the community for this project. In the community reporting process, the investigators explained to the community that information generated in the FG or KI interviews were grouped into positive, unique, and negative. The list of sentences and phrases are shared with the community without indicating how the students/investigators classified this information. The community, as a group, was then asked to group this list of information into one of the following: (a) positive and supportive of PLWHA, (b) unique and has no impact on stigma, or (c) negative and stigmatizing. Following the classification by the group or community, the students/investigators then shared with the group how they had classified the same information. The goal was to not influence how the community judged the information generated in the FG but to have an opportunity to learn from the community while sharing with its members the perspective of the investigators where there were opposing views. In this exercise, the views of the students/investigators were consistent with those of the community, and hence the three themes presented in the Results and Discussion sections.

RESULTS

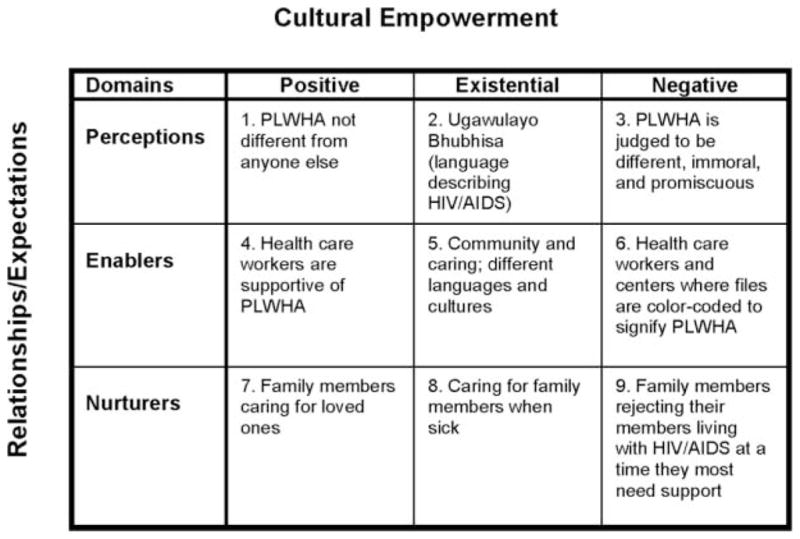

In the assessment phase of PEN-3, as indicated earlier, the researchers engaged the community in completing a 3 × 3 table by crossing CE (positive, existential, negative) and RE (perception, enabler, nurturer) to produce nine categories, as seen in Figure 2. As noted, some themes appeared in more than one category. However in this article, we generated three cross-cutting themes.

Figure 2. PEN-3 Table of Analysis With Examples of Each Category.

NOTE: PLWHA = people living with HIV and AIDS.

In PEN-3, interventionists are required to begin with the positive aspects of culture and behavior (Airhihenbuwa, 1999, 2007a, 2007b) rather than focusing only on the negative, as is generally the case in community-based intervention studies. Although we presented the results under three subheadings, we used the titles of the nine categories (e.g., positive perception) in the assessment phase of PEN-3 to illuminate the results so as to demonstrate actions in families and health care centers that are positive or nonstigmatizing and should be promoted (from the outside looking in), existential or unique to be acknowledged (from the inside looking out), and negative or stigmatizing and should be changed (the mirror sees both sides). African proverbs are included with each theme to anchor the comments in identity and language.

FROM THE OUTSIDE LOOKING IN

If you want someone more knowledgeable than yourself to identify a bird, you do not first remove the feathers.

—Ugandan proverb

One very important group whose views typify those on the outside looking into the lives of PLWHA are people who have not been tested for HIV. A community dialogue should begin with the knowledge and openness that the views of the community are fully encouraged without distortions of the subject matter. Positive perceptions in the PEN-3 means that community dialogues should not begin with an a priori negative notion of the subject matter or how the researcher predetermines it should be addressed. Such a practice typically silences voices from the community, such as the one of this participant: “In your family if you’ve grown up to be close to each other and things like that, and caring and supporting, I don’t see that HIV must take away that bond, you know.” One form of silencing is in beginning a dialogue with highlights of “negatives” instead of “positives.” It is only when we engage communities and families in a dialogue of possibilities that we hear comments such as, “People who are HIV positive, who are open about their status, show the people that if you are HIV positive you are no different from someone who is negative.” Although we want to also identify the negative to be changed, as will be discussed later, we always begin with the positive because it affirms the values of the collective and ensures that even the negative can be changed and sustained beyond the life of the project, in spite of the difficulties. It is very helpful to hear the voice of someone who has overcome initial difficulties and now has the support of friends and loved ones, as the participant who said, “At first it was an adjustment but it is no longer difficult anymore and what helps me, you can talk safely with your friends and I’m no longer ashamed over the matter.” Beyond these individual perceptions are acknowledgements of health care providers and families as positive enablers.

With so much written about the negative roles of health care providers in HIV-related stigma, it should be acknowledged that health care is a system and that a system can also be a positive enabler. A Nigerian proverb states, “Even the Niger River must flow around an island.” Systems and structures influence and shape the way we behave, whether positive or negative. We cannot fully understand personal behavior unless we understand the structures and systems that influence these behaviors. The degree to which experiences are positive or negative depends to a large degree on the policy that shapes those experiences. In spite of the devastation of HIV and AIDS, there are positive actions by health care providers that are experienced by some PLWHA, as evident in these comments by a participant:

Health employees have treated me well. . . . I would come and eat the tablets, then when we leave they would give us porridge from there so that when you arrive at home you will first have to eat that porridge and then drink the pills.

These positive experiences are enabled through supportive roles of government and institutions at the local and national levels. Local primary health care centers in many areas with high numbers of people living with HIV in South Africa have been described as being very effective in providing care and support to PLWHA, although they have limited resources.

At the hospital or clinic I have received a lot of support; I do not want to lie. I attend a clinic at KTC after I was transferred from Gugulethu NY1 because I am on drugs [antiretroviral]. The support I receive there is good and I think that they treat us the same.

Some positive comments about health care settings showed that counselors were particularly praiseworthy:

Especially the counselors, they are the ones who help the living with the disease of Isifo sikaGawulayo [HIV and AIDS]. They would also tell someone to follow a certain kind of diet that is healthy and … must use condom when engaging in sex. I prefer them to doctors.

Similar positive experiences at health care centers were also noted within families, as families were recognized as positive nurturers.

A South African proverb asks, “Before the drawing board, where did they go back to?” This is a different version of a Nigerian proverb that states, “Before the advent of the corn, the chicken must have fed on something.” One very important reason we must begin with the positive is that one can begin to develop possibilities (positive nurturers in PEN-3) for an intervention at the outset by identifying key members of the family and health care centers who have made a difference in the life of a PLWHA and could be an intervention point of entry: “But my sisters played a very cardinal role to assist me; they even go as far as giving examples of other people who lived with the virus for many, many years including Nkosi Johnson.” Developing an intervention should not always begin with importing an idea from the outside. Looking within allows us to highlight specific kinds of support that were considered comforting:

We receive support from the family because they pay funeral cover for the community funeral scheme (umasigcwabane). . . . They buy you things when they come back from work because when you have this thing there are times you do not want to eat what others are eating.

Successful interventions can occur by looking within to understand how related issues have been addressed in the past. The role and composition of family becomes very important in this area. Knowing how families (the primary nurturing unit) and health centers (the primary enabling unit) have been connected is central to developing a sustainable intervention:

But then we do have even families that come with our clients to the clinic, and things like that, supportive. And also mothers, some mothers and fathers coming with their children to the clinic so, ya, there is hope and there is support in some families.

In this way, the two primary contexts of our study (family and health care centers) are connected. From here, we can begin to examine certain unique qualities within the family and health care settings.

FROM THE INSIDE LOOKING OUT

Only a knife knows what the inside of a coco-yam looks like.

—Mali proverb

In discussing HIV stigma in South Africa, a participant noted, “We having names like Z3, a slang that is used to refer to someone who is HIV positive,” indicating that HIV is like a trendy fast car such as the Z3. As one participant stated,

People who are affected by Ugawulayo [HIV/AIDS] ought to be understood by his or her family, even if one form of sickness is not different from the other, but the issue of Ugawulayo has been given much attention as Bhubhisa [killer disease].

Community members know the relevance of these words and how they should be employed in intervention. When asked the circumstances surrounding their disclosure, one participant responded,

I told them that it doesn’t help to hide, pretend as if I’m not sick, whereas I am dying. They know outside that even if you die, people will say, No he was just hiding that he had Ugawulayo [AIDS]. So they know that even if I can die, they must not hide people; they must tell people that he was just sick once and for all.

Beyond the individual perceptions about HIV, unique family values underscore the importance of identity and belonging in studying stigma in South Africa.

There are many aspects of a culture that are understood only from within, hence the need to identify existential enablers in PEN-3. A Ghanaian proverb states, “The family is like the forest; seen from the outside, it appears dense; experienced from the inside, you come to understand that each tree has its own role and position.” The community plays a critical role in how values in the culture are reinforced to help normalize the lives of those who are sick. The level of support in a community is also mediated by the degree to which services offered are aligned with certain forms of cultural identity:

People don’t look at you as before, and things get better and better; the people understand what HIV is all about. There are certain people in the community that goes for the counseling course and so on, so they can know what it is all about so that they do not criticize other people. Some community members attend our workshops. Most people are learning and attending HIV/AIDS functions. Some community members were respectful; others brought food for us.

In South Africa, the legacy of apartheid that continues to thwart the celebration of diversity in its language and culture sometimes means that health care providers have difficulties communicating with their patients when the provider does not speak or understand the patient’s language and culture, even though they are both South Africans:

Very often the patients we deal with here come from a rural African setting. And very often the doctors that you have here are not from an African setting. Hmm, there are doctors from I would say more affluent settings, different cultures, and as a result you find that sometimes it is difficult to communicate. Not only because of the language barrier but because of the cultural barrier.

Thus, the role of language, particularly in communications, becomes very important. Even with the challenge of language differences in a country, there are nurturing experiences to be acknowledged.

We encourage nurturing the uniqueness of cultures and contexts (existential nurturers in PEN-3) by not losing their meanings in the disease that may signify a broader problem. For example, in the United States, Native Americans have often been treated as if diabetes is the only referent by which they must be defined as a people, with little or no reference to their rich and unique cultures. Our goal is to not undermine the seriousness of HIV and AIDS in South Africa but to also not undermine the broader cultural richness that defines South Africans beyond HIV and AIDS. Nurturing is culturally produced and maintained, and a study of stigma is bound to generate ways in which the notions of shame and rejection are expressed in each culture and context. Food, for example, represents a form of nurturance that is a cornerstone in the bonding that is established in the family: “My family is good to me, and they share everything. And we eat and drink still out of one cup, and so, and they understand me. Even I cook for them and they eat.” Beyond the physical ingestion, food becomes an important way to contextualize relations and connectedness in a culture in ways that could inform sustainable intervention. In fact, the “strangeness” of the HIV disease has ushered in behaviors that may appear strange, particularly among those who are the most caring and supportive of their family members. Although some traditional practices may seem different, examining the sociocultural context within which such practices take place provides better insight. The paths to cultural practices (or context) may be strange to the outsiders but never to the communities or its leaders. Failure to understand the value of relations and connectedness in the community could result in an intervention recommendation that is forgotten as soon as the meeting is over. This is one more reason that we must examine the context of negative individual behaviors.

THE MIRROR SEES BOTH SIDES

Until the lions produce their own historians, the story of the hunt will glorify only the hunter.

—Nigerian proverb

To focus on the positive and neutral is a necessary path to having a clearer understanding of the negative. With the positive and neutral in the background, the negative is better understood as a product of contexts and structures. Within these contexts and structures are elements of history and politics and, indeed, human responses to and interpretations of them. These interpretations may be mirrored spiritually in a comment such as, “They hide their status because they think that they are immoral and know that people will not accept them. Some people label the person, and they feel guilty because they associate it with promiscuous life.” History and politics are the shells that preserve group and personal behaviors. The evidence of negative stigmatizing discourses was powerfully illustrated in a participant’s narrative that says, “Many people they still look at you thinking that you have to be sick and you have to be thin before you can have HIV, you know.” In this respect, the negative association of HIV/AIDS with women was particularly salient:

In the community, women are criticized often. Women are stigmatized more because of the assumption that they are promiscuous. In marriage, it is important to know your partner’s business although you would not know what he did before you got married.

The blaming of one group by another leads to marginalization of other groups and a poor sense of security by the group that assigns blame. Historically, women have been blamed and often expected to be solely responsible for the health of the family and community.

There are many aspects of the political histories of a context that act as negative enablers for those in the community. For example, the moral taboos of sexuality that are commonly used to differentially marginalize women (compared to men) have left many African women more vulnerable to stigma.

Ooh women, they easily ask you as women: Now where do you think did you get this thing or when did it happen, or things like that. Or they’ll think that maybe you were flirting around, or things like that you know, but to men they won’t easily ask that question: Now were you involved with someone else or did you have an affair, or things like that you know, but they’ll usually ask that to a woman.

Women nurture the family, and women are also more likely to use health care centers for themselves, their children, or their family members. Vulnerability, therefore, occurs at multiple levels. There is a commonly referenced vulnerability from engaging in sex with a partner who may be HIV positive. There is also the vulnerability that results from using health services more often than men do and being primarily responsible for the health and nurturance of the family.

They still discriminating even on the folders of the clients, because the folders have a mark on them, so if the person goes to the front or to wherever, the chemist maybe, the people that work in that system, would see that: Oh this is the mark, oh. So they know that this person is HIV positive.

In a system where there are adequate health facilities, it is a positive enabler to use health care services. However, in a system where health care is inadequate and workers are overworked and have limited opportunity for retraining, women, by virtue of visiting health care facilities more often than men do, are more likely to encounter stigma in health care settings. The higher rate of health care use by women can be understood as women seeking care for reproductive health and care for their children. Motherhood thus becomes an important identity that offers a different, and perhaps a deeper, understanding of the contexts of stigma for South African women.

Indeed, the fear of HIV typically manifests in the contexts of family and health care settings, even though these fears are captured at the individual level. A Nigerian proverb laments, “A thief is never as ashamed as his parents.” Such stigma has led to some families and communities actively rejecting loved ones with HIV/AIDS:

I live with other people and I have two children. The baby is also HIV positive, and my aunty found out. And my aunty rejected me, and my aunt didn’t want me to stay there. When people don’t want to share it’s painful to think your own family rejects you and outside people accept you as you are.

Another participant commented, “It is to larger extent painful especially with the way her brothers or her sisters treat her. You notice that they don’t even eat food prepared by HIV-positive person.” Others have engaged in exclusionary practices such as the denial of sharing clothes or eating together as traditionally practiced, as illustrated by this participant:

I found it difficult to disclose my status to my family and friends. When I prepare and dish out food, my family does not accept the food for fear that they might be infected. If there was education about how HIV/AIDS is transmitted, I am sure the situation would be different.

These negative nurturers become the basis on which to build a community dialogue that focuses on sustainable intervention. As we noted earlier, we must always begin with the positive.

DISCUSSION

Current research on HIV/AIDS prevention and care of PLWHA in South Africa reveals that the social and cultural dynamics of the disease need to be understood if we are to have a broader appreciation for the nature and role of stigma in its spread. Culture is defined as a collective sense of consciousness (Airhihenbuwa, 2007a) that is anchored in a shared history, linguistic code, and psychological lineage (Diop, 1991). The importance of focusing on culture in public health interventions is born of the realization that (a) culture shapes behavior in general and health behavior in particular (Dutta-Bergman, 2004; Niang, 1994); (b) an individually based approach to behavior change is not adequate for HIV/AIDS prevention, care, and support in Africa and in other non-Western contexts (UNAIDS/Penn State, 1999); and (c) knowledge alone does not lead to behavior change (Freimuth, 1992; Yoder, 1997). This realization has led to a call by public health scholars to transform approaches to HIV/AIDS by addressing the social contexts of behavior in general (Kelly, 1999; McKinlay & Marceau, 2000) and the contexts of stigma in particular (Deacon et al., 2005; Parker & Aggleton, 2003). In South Africa, a community dialogue is one strategy used to reduce stigmatization of PLWHA (POLICY Project et al., 2002, 2003).

The persistence of “blaming discourses,” as elaborated by Petros, Airhihenbuwa, Simbayi, Ramlagan, and Brown (2006), resulting in prejudice, discrimination, and abuse in many contexts was also well illustrated by participants. The impact of political history, specifically the history of apartheid in South Africa, cannot be ignored. Indeed, the blaming of women for societal ills has a deeper and longer problematic history than HIV and AIDS. The Edos of Nigeria would say, “Motherhood has no rejects,” which is a different way of saying that “motherhood is supreme” (see Oyewumi, 1997). While a “supernatural” interpretation of illness that locates the liability for transmission outside human agency might mobilize social solidarity against the disease, a “physical” interpretation that places responsibility for the spread of disease on individual control and abnormality may reinforce social stereotypes. Such stereotypes encourage prejudice and stigmatization of the disease and discrimination and victimization of those affected (Seidel, 1993).

In a community dialogue, or what Airhihenbuwa (1995, 2007a) refers to as a “polylogue,” attention must be paid to language used, expressions (verbal and nonverbal) used for communication, and meanings ascribed to what is being discussed. In existential perception of the PEN-3, we know that words may remain the same, but their meanings change as they cross cultural boundaries. The importance is not always the etic (scientific) accuracy of usage but rather the emic (cultural and community understanding) of what is being discussed.

A study conducted among nearly 500 people in a Cape Town township in 2003 found that individuals who had not been tested for HIV held significantly more stigmatizing attitudes toward PLWHA than did individuals who had been tested (Kalichman & Simbayi, 2003). To a high degree, those who have not been tested function as outsiders looking in and feed into the fear of HIV and AIDS that in part perpetuates stigma. For them, a community dialogue whereby positive and nonstigmatizing practices are discussed is an important strategy to reduce and eliminate stigma.

In 2002 and again in 2005, the Nelson Mandela Foundation and the HSRC published results from a population-based HIV sero-prevalence, behavioral risk, and media impact study conducted in South Africa (Shisana et al., 2005), which show that AIDS-related stigma remains prevalent in South Africa. A recent survey conducted among 1,054 PLWHA in Cape Town found that PLWHA had high levels of stigma (Simbayi et al., 2007b), a large number of whom had not disclosed their HIV-positive status for fear of stigma and discrimination (Simbayi et al., 2007a), corroborating previous studies and reports (Bollinger, 2002; Deacon et al, 2005).

To effectively transform the contexts of stigma (negative nurturers in PEN-3), an African-centered context for framing womanhood in general and motherhood in particular offers a constructive process for understanding that, as much as motherhood is the cultural womb of a society (Airhihenbuwa 2007a), the societal burden cannot be understood by focusing only on her behavior without an assessment of her contexts (Airhihenbuwa, 2007b; Oyewumi, 2003). Rather, she (motherhood) nurtures the family and institutions that have been historically produced, politically rewarded, and institutionally reinforced for her and her family. A proverb from the Democratic Republic of Congo reminds us that “a single bracelet does not jingle.” A pandemic that affects millions, such as HIV and AIDS, will not respond to a focus on only individual behavior. Thus, interventions ought not to focus on women’s behavior at the exclusion of their sociocultural, historical, and political contexts.

Having framed relevant sociocultural issues into appropriate themes, in PEN-3, a collective decision must be made among the researchers and members of the community to prioritize the point of intervention entry (the CI dimension). Such entry (the person, the extended family, or the neighborhood/community) is based, in part, on culture-centered experiences about the context of successful prevention and the likelihood that the entry chosen this time will lead to a significant change in reducing stigma by promoting positive behaviors and changing negative ones. In a conventional model, we often begin the intervention by discussing the individuals. In the PEN-3 model, the CI domain is the last component because it is the nature and context of the issues that determine which of the CI categories should be the focus of intervention. In this ongoing study, the results of the intervention will be reported in future publications.

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

Findings are limited based on the selectivity of the people who participated. However, keeping findings in context is a cardinal principle of qualitative analysis. Another limitation concerns the varying degree of openness expressed by participants in response to the questions. Because the study questions focused on sociocultural issues related to HIV/AIDS, some of the participants, specifically the KIs among health care workers, may have been less open about sharing both positive and negative information about their coworkers but responded generally or in reference to other health care settings.

CONCLUSION

The question of stigma and its role in the spread of HIV/AIDS in South Africa and the care of those living with HIV/AIDS offers an opportunity to examine the question of the intersection of culture and identity. We believe that while individuals may exhibit stigmatizing actions, the root causes of these actions are better understood in their social and cultural contexts. Indeed, the family and health care centers are two key contexts that cannot be avoided by PLWHA. Everyone has a family, and every person diagnosed with an illness needs health services for care; hence, we focus on these two contexts. We characterize our findings about stigma as being on the outside looking in, as being on the inside looking out, or as a mirror with two sides. We believe that a cultural model like PEN-3 offers the possibility of developing an effective cultural analysis on which an effective intervention can be developed to reduce and eliminate HIV/AIDS-related stigma.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, No. R24 MH068180. We thank the following students for participating in data collection: Vuyisile Mathiti, Heidi Wichman, Tshipinare Marumo, Shahieda Abrahams, Thandiwe Chihana, Nashrien Khan, Roro Makubalo, Xolani Nibe, Gail Roman, Matlakala Pule, and Nadira Omarjee. For human participant protection, the study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of Penn State University and the Human Sciences Research Council of South Africa. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Footnotes

While we do not endorse the historical apartheid classification system, these categories continue to be used by the South African government for the purposes of social redress and equity and still have salience in South African communities today.

Contributor Information

Collins Airhihenbuwa, Penn State University, University Park.

Titilayo Okoror, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana.

Tammy Shefer, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa.

Darigg Brown, Penn State University, University Park.

Juliet Iwelunmor, Penn State University, University Park.

Ed Smith, Penn State University, University Park.

Mohamed Adam, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa.

Leickness Simbayi, Human Sciences Research Council, Cape Town, South Africa.

Nompumelelo Zungu, Human Sciences Research Council, Cape Town, South Africa.

Regina Dlakulu, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa.

Olive Shisana, Human Sciences Research Council, Cape Town, South Africa.

References

- Abernethy AD, Magat MM, Houston TR, Arnold HL, Jr, Bjorck JP, Gorsuch RL. Recruiting African American men for cancer screening studies: Applying a culturally based model. Health Education and Behavior. 2005;32:441–451. doi: 10.1177/1090198104272253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Airhihenbuwa CO. Perspectives on AIDS in Africa: Strategies for prevention and control. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1989;1(1):57–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Airhihenbuwa CO. Health and culture: Beyond the Western paradigm. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Airhihenbuwa CO. Of culture and multiverse: Renouncing “the universal truth” in health. Journal of Health Education. 1999;30:267–273. [Google Scholar]

- Airhihenbuwa CO. Healing our differences: The crisis of global health and the politics of identity. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield; 2007a. [Google Scholar]

- Airhihenbuwa CO. On being comfortable with being uncomfortable: Centering an Africanist vision in our gateway to global health (2005 SOPHE Presidential Address) Health Education and Behavior. 2007b;34:31–42. doi: 10.1177/1090198106291377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alubo O, Zwandor A, Jolayemi T, Omudu E. Acceptance and stigmatization of PLWA in Nigeria. AIDS Care. 2002;14:117–126. doi: 10.1080/09540120220097991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardnt C, Lewis JD. The HIV/AIDS pandemic in South Africa: Sectoral impacts and unemployment. Journal of International Development. 2001;13:427–449. [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann MO, Booysen FLR. Health and economic impact of HIV/AIDS on South African households: A cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2003;3(14):1–8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-3-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beech BM, Scarinci IC. Smoking attitudes and practices among low-income African Americans: Qualitative assessment of contributing factors. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2003;17(4):240–248. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-17.4.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollinger L. Unpublished manuscript. 2002. Stigma: Literature review of general and HIV-related stigma. POLICY Project. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C, Foulis CA, Maimane S, Sibiya Z. I have an evil child at my house”: Stigma and HIV/AIDS management in a South African community. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:808–815. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.037499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Deacon H, Stephney I, Prosalendis S. Understanding HIV/AIDS stigma: A theoretical and methodological analysis. Cape Town: South Africa: HSRC Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. Handbook of qualitative research. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Desmond C, Michael K, Gow J. The hidden battle: HIV/AIDS in the household and community. South African Journal of International Affairs. 2000;7(2):39–58. [Google Scholar]

- Diop CA. Civilization or barbarism: An authentic anthropology. New York: Lawrence Hill; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Draper B, Pienaar D, Parker W, Rehle T. Recommendations for policy in the Western Cape Province for the prevention of major infectious diseases, including HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis. 2007 Retrieved on March 26, 2008, from http://www.capegateway.gov.za/eng/pubs/reports_research/W/157844.

- Du Bois WEB. The Philadelphia Negro: A social study. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1996. (Original work published 1899) [Google Scholar]

- Dutta-Bergman M. The unheard voices of Santalis: Communicating about health from the margins of India. Communication Theory. 2004;14:237–263. [Google Scholar]

- Erasmus Z, Pieterse E. Conceptualising Coloured identities in the Western Cape Province of South Africa. In: Palmberg M, editor. National identity and democracy in Africa. Cape Town, South Africa: Human Sciences Research Council and Mayibuye Centre of the University of the Western Cape; 1999. pp. 167–187. [Google Scholar]

- Erwin DO, Johnson VA, Trevino M, Duke K, Feliciano L, Jandorf L. A comparison of African American and Latina social networks as indicators for culturally tailoring a breast and cervical cancer education intervention. Cancer. 2007;109(2 suppl):368–377. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanon F. Black skin, White mask. New York: Grove Weidenfeld; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Fassin D, Schneider H. The politics of AIDS in South Africa: Beyond the controversies. British Medical Journal. 2003;326:495–497. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7387.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick L, McCray E, Smith DS. The global HIV/AIDS epidemic and related mental health issues: The crisis for Africans and Black Americans. Journal of Black Psychology. 2004;30:11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault M. The history of sexuality. Vol. 1: An introduction. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin; 1978. (Original work published 1976) [Google Scholar]

- Freimuth VS. Theoretical foundations of AIDS media campaigns. In: Edgar T, Fitzpatrick MA, Freimuth VS, editors. AIDS: A communication perspective. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1992. pp. 91–110. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on management of spoiled identity. New York: Simon & Schuster; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman RM, Yoo S, Jack L. Applying comprehensive community-based approaches in diabetes prevention: Rationale, principles, and models. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 2006;12:545–555. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200611000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groenewald P, Nannan N, Bourne D, Laubscher R, Bradshaw D. Identifying deaths from AIDS in South Africa. AIDS. 2005;19:193–201. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200501280-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Capitanio JP, Widaman KF. HIV-related stigma and knowledge in the United States: Prevalence and trends, 1991–1999. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:371–377. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.3.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James DC. Factors influencing food choices, dietary intake, and nutrition-related attitudes among African Americans: Application of a culturally sensitive model. Ethnicity and Health. 2004;9:349–367. doi: 10.1080/1355785042000285375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC. HIV testing attitudes, AIDS stigma and voluntary HIV counseling and testing in a black township in Cape Town, South Africa. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2003;79:442–447. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.6.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi L. Traditional beliefs about the cause of AIDS and AIDS-related stigma in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2004;16:572–580. doi: 10.1080/09540120410001716360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JA. Community-level interventions are needed to prevent new HIV infections. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89:299–301. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.3.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumanyika SK, Obarzanek E. Pathways to obesity prevention: Report of a National Institutes of Health workshop. Obesity Research. 2003;11:1263–1274. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinlay JB, Marceau LD. To boldly go. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:25–33. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niang CI. The Dimba of Senegal: A support group for women. Reproductive Health Matters. 1994;4:39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Oyewumi O. The invention of women: Making an African sense of Western gender discourses. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Oyewumi O. African Women and feminism: Reflecting on the politics of sisterhood. Trenton, NJ: African World Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Parker R, Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: A conceptual framework and implications for action. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;57:13–24. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petros G, Airhihenbuwa CO, Simbayi LC, Ramlagan S, Brown B. HIV/AIDS and “othering” in South Africa: The blame goes on. Culture, Health and Sexuality. 2006;8(1):67–77. doi: 10.1080/13691050500391489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POLICY Project, Centre for the Study of AIDS (University of Pretoria), United States Agency for International Development, & Chief Directorate: HIV/AIDS & TB, Department of Health. Siyam’kela: Measuring HIV/AIDS related stigma: Literature Review. Cape Town, South Africa: POLICY Project; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- POLICY Project, Centre for the Study of AIDS (University of Pretoria), United States Agency for International Development, & Chief Directorate: HIV/AIDS & TB, Department of Health. Siyam’kela: Examining HIV/AIDS stigma in selected South African media: January–March 2003: A summary. Cape Town, South Africa: POLICY Project; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Flannery D, Rice E, Lester P. Families living with AIDS. AIDS Care. 2005;17:978–987. doi: 10.1080/09540120500101690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarinci IC, Silveira AF, Figueiredo dos Santos D, Beech BM. Sociocultural factors associated with cigarette smoking among women in Brazilian worksites: A qualitative study. Health Promotion International. 2007;22:146–154. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dam012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidel G. The competing discourses of HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa: Discourses of rights and empowerment vs. discourses of control and exclusion. Social Science and Medicine. 1993;36:175–194. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90002-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi LC, Parker W, Zuma K, Bhana A, et al. South African National HIV prevalence, HIV incidence, behaviour and communication survey. Cape Town, South Africa: HSRC Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Shisana O, Simbayi L. Nelson Mandela/HSRC study of HIV/AIDS: South Africa national HIV prevalence, behavioural risks and mass media, household survey. Cape Town, South Africa: Human Sciences Research Council; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Simbayi LC, Kalichman SC, Strebel A, Cloete A, Henda N, Mqeketo A. Disclosure of HIV status to sex partners and sexual risk behaviors among HIV positive men and women in Cape Town, South Africa. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2007a;83:29–34. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.019893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simbayi LC, Kalichman SC, Strebel A, Cloete A, Henda N, Mqeketo A. Internalized AIDS stigma, AIDS discrimination, and depression among men and women living with HIV/AIDS, Cape Town, South Africa. Social Science and Medicine. 2007b;64:1823–1831. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics South Africa. Income and Expenditure Survey 2000. Pretoria: Author; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. Report on the global AIDS epidemic/UNAIDS. Geneva, Switzerland: Author; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Airhihenbuwa CO, Makinwa B, Frith M, Obregon R, editors. UNAIDS/Penn State. Communications framework for HIV/AIDS: A new direction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Underwood S, Pridman K, Brown L, Clark T, Frazier W, Limbo R, et al. Infant feeding practices of low-income African American women in a central city community. Journal of Community Health Nursing. 1997;14:189–205. doi: 10.1207/s15327655jchn1403_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker C. An educational intervention of hypertension management in older African Americans. Ethnicity and Diseases. 2000;10:165–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder PS. Negotiating relevance: Belief, knowledge, and practice in international health projects. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 1997;11:131–146. doi: 10.1525/maq.1997.11.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]