Abstract

Parkinson’s disease (PD), the second most common neurodegenerative disorder, is characterized by marked impairments in motor function caused by the progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc). Animal models of PD have traditionally been based on toxins, such as 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) and 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP), that selectively lesion dopaminergic neurons. Motor impairments from 6-OHDA lesions of SNc neurons are well characterized in rats, but much less work has been done in mice. In this study, we compare the effectiveness of a series of drug-free behavioral tests in assessing sensorimotor impairments in the unilateral 6-OHDA mouse model, including six tests used for the first time in this PD mouse model (the automated treadmill “DigiGait” test, the challenging beam test, the adhesive removal test, the pole test, the adjusting steps test, and the test of spontaneous activity) and two tests used previously in 6-OHDA-lesioned mice (the limb-use asymmetry “cylinder” test and the manual gait test). We demonstrate that the limb-use asymmetry, challenging beam, pole, adjusting steps, and spontaneous activity tests are all highly robust assays for detecting sensorimotor impairments in the 6-OHDA mouse model. We also discuss the use of the behavioral tests for specific experimental objectives, such as simple screening for well-lesioned mice in studies of PD cellular pathophysiology or comprehensive behavioral analysis in preclinical therapeutic testing using a battery of sensorimotor tests.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, 6-OHDA, mouse, behavioral test, sensorimotor impairment, medial forebrain bundle

1. Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc), which leads to severe motor impairments, including bradykinesia, akinesia, muscular rigidity, altered gait, resting tremor, and postural instability [1, 2]. PD is primarily a ‘sporadic’ disease and although a number of environmental and genetic risk factors have been identified, the exact cause in the majority of cases remains unknown [2–4].

A classic animal model of PD, used for over 40 years, is based on intracranial injection of the toxin 6-OHDA in the rat, which leads to a selective loss of nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons [2, 5–7]. The intracranial route of delivery is necessary since 6-OHDA does not cross the blood brain barrier [2, 8, 9]. To model PD conditions, 6-OHDA can be injected either into the SNc, the medial forebrain bundle (MFB) containing the ascending nigrostriatal fibers, or the striatum. 6-OHDA injections in the MFB or SNc produce a near complete lesion of nigrostriatal neurons that is comparable to neuronal loss in late-stage PD patients. In contrast, 6-OHDA injections in the striatum yield a more progressive and less extensive lesion of nigrostriatal neurons, which may better emulate earlier stages of PD [2, 10]. 6-OHDA injections are typically done unilaterally, which allows for an easy comparison of motor impairment between the contralateral, impaired side vs. the ipsilateral, unimpaired side of the body. The unilateral 6-OHDA rat model has been widely used in studies of PD pathophysiology [11–16] and for preclinical testing of therapeutic approaches such as deep brain stimulation [17–19] and gene therapy for late-stage PD [20–25].

Behavioral assessments of motor impairments in the unilateral 6-OHDA rat model were initially done by amphetamine- or apomorphine-induced rotation tests [26]. However, since repeated administration of psychostimulants causes changes in synaptic function and dendritic morphology [27, 28], the use of drug-induced rotation tests has been replaced in many studies by drug-free sensorimotor behavioral tests. For example, unilateral 6-OHDA-lesioned rats show robust limb-use asymmetry in the cylinder test, akinesia in the stepping test, altered stride length in gait analysis, and impairments in the adhesive removal test [29–33]. Recently, many laboratories have begun to use mice in PD research because of the availability of mouse models carrying genetic mutations linked to familial forms of PD [34–36] and transgenic mice expressing fluorescent proteins targeted to different cell types in the basal ganglia [37]. Therefore, we wanted to establish a comprehensive set of behavioral tests to measure sensorimotor impairments in 6-OHDA mice that can be applied to future PD studies with 6-OHDA-lesioned mice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Animals

All animals used in this study were wildtype male C57BL/6 mice (Charles River). All procedures were conducted in accordance to protocols approved by the Northwestern University Animal Care and Use Committee (ACUC), and were in compliance with the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide to the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The mice were provided with food and water ad libitum and kept in 12-hour light/dark cycles.

2.2 6-OHDA and saline MFB injections

6-hydroxydopamine and saline injections were performed in male C57BL/6 mice at 3–5 weeks of age. The surgical procedure for 6-OHDA and saline injections was modified based on previously established protocols for 6-OHDA injections in rats [12] and for general stereotaxic injections in mice [38]. Animals were anesthetized using 1–1.5% of isofluorane, mixed with oxygen, and placed in a small animal stereotaxic frame (Kopf Instruments, CA). After making a small incision to expose the scalp, a bone scraper was used to clean the skull above bregma and lambda and a dental drill (Osada, EXL-M40) was used to make a small craniotomy above the MFB. 6-OHDA (free base) was dissolved in saline (0.9% w/v NaCl with 0.1% w/v ascorbic acid), to a final concentration of 2.5mg/ml, immediately before use to minimize the oxidative effects on 6-OHDA. A total volume of 1μl of 6-OHDA (2.5 μg) or saline was injected at a rate ~200 nl/min into the MFB (at AP −0.7mm and ML 1.1mm from bregma, and DV 4.8mm from the exposed dura surface). Injections were performed using a micropipette (VWR) pulled with a long narrow tip (diameter= 6–9 μm) using a micropipette puller (Sutter Instrument, Co.). Micropipettes were calibrated to inject 90nl of liquid for every 1mm, as modified from [38]. Following surgery, the scalp was sutured and topical antibacterial ointment (Topazone) was applied. Analgesic (meloxicam: 1mg/kg, i.p.) was administered after the surgery and daily until animal’s recovered based on grooming and overall appearance. Mice were kept continuously on a heating pad (~35°C), given daily injections of saline (500μl, s.c.), and fed a dietary food supplement Pediasure (ad libitum) until they returned to their pre-surgery weight. The post-operative mortality rate was 14.7%.

2.3 Behavior

When using multiple tests on the same group of animals, the behavioral tests were performed in the same order for both experimental groups. For all non-automated tests, the behaviors were scored by an investigator who was blind to the treatment condition.

2.3.1 Limb-Use Asymmetry (Cylinder) Test

Mice were tested, under low light conditions, in the evening prior to the onset of the dark cycle. These testing conditions increased the overall movement and rearing of the mice in the cylinder and allowed us to obtain sufficient data during repeated testing, which otherwise led to habituation and a decrease in rearing (data not shown). The cylinder test was modified from the original paradigm used in rats [29] and behavioral impairment in this test was shown to be ameliorated following dopamine agonist treatment in 6-OHDA mice [39, 40]. Animals were placed in a glass cylinder (8 cm diameter and 11 cm height for mice) and recorded for 5–10 minutes. The cylinder was placed next to a mirror in order to visualize limb use movements from all angles (Supplementary Video 1a, 1b). Forelimb asymmetry was assessed by scoring independent, weight-bearing contacts on the cylinder wall of the ipsilateral (ipsi) or contralateral (contra) paw, relative to lesioned hemisphere, as well as movements made by both paws (both). The percentage of ipsilateral and contralateral touches, relative to the total number of touches (ipsi+contra+both = total), was calculated.

2.3.2. Automated Treadmill Gait Test

Treadmill gait assessment was performed with the DigiGait imaging apparatus (Mouse Specifics, Inc.) [41]. Gait impairment was previously shown to be ameliorated by pharmacological dopamine treatment in MPTP treated mice [42]. Mice were placed on a motorized treadmill within a plexiglass compartment (~25 cm long and ~5cm wide). Digital video images were acquired at a rate 80 frames per second by a camera mounted underneath the treadmill to visualize paw contacts on the treadmill belt. The treadmill was set at a fixed speed of 16 or 18 cm/sec at which most animals were able to move continuously (Supplementary Video 2a, 2b) [41, 43]. A plastic bumper, located near the rear of the mouse, was used to nudge the mice to encourage movement if they stopped running while the treadmill was moving. The videos were analyzed by the DigiGait software, which automatically identifies the paw footprints, and then manual alterations in the contrast of the images were made, if necessary, to properly distinguish the footprints from the background. The images were then automatically processed by the software to calculate values for multiple gait parameters, including stride width, stride length, paw angle, and stride length variability (see Supplementary Figure 3).

2.3.3. Manual Gait analysis

Manual gait analysis was performed using a limb painting procedure similar to previous studies [44–47]. Gait impairment was shown to be ameliorated by dopamine agonist treatment in MPTP mice [42]. Mice were first trained to traverse a horizontal corridor leading directly into their home cage by gentle nudges in the appropriate direction if they stopped or attempted to turn around. After training, mice were injected with 6-OHDA or saline and tested at 3 weeks after surgery. The bottoms of their hindlimbs were painted, by brushing with non-toxic kids paint (Crayola LLC), and the mice were allowed to walk the path to their homecage on a piece of paper (Supplementary Video 3a, 3b). The stride length was determined by measuring the distance between the same points, on the ball mount region of the footprint, in two consecutive footprints. Stride length was calculated from 2–3 hindpaw strides when the animal was walking continuously at a constant pace. Steps just before the entry to the homecage were not included since mice often slowed down and made smaller steps at this point. Median data from 4–6 strides across the two trials were calculated.

2.3.4 Challenging Beam Test

The challenging beam test was performed according to previous studies in Parkinsonian genetic mouse models [46, 48–52] and impairment in the beam test was reversed following dopamine agonist treatment in a Parkinsonian genetic mouse model [50]. The beam, made of Plexiglas (Plastics Zone Inc., Woodland Hills, CA), consisted of four sections (25 cm each) of decreasing width (3.5 cm to 0.5 cm at 1 cm decrements), with an underhanging ledge (1 cm width) that was placed 1.0 cm below the upper surface of the beam. Two days of training were performed prior to the surgery. For post-surgical testing (at 3 weeks after surgery), a mesh grid (1 cm squares) of corresponding width was placed over the beam surface, leaving approximately 1 cm space between the grid and the beam surface. Animals were then videotaped while traversing the grid-surfaced beam for a total of five trials after the surgeries (Supplementary Video 4a, 4b).

Videotapes were viewed and scored in slow motion for the number of errors, number of steps, and time to traverse the beam across five trials. An error was counted when, during a forward movement, a limb (forelimb or hindlimb) slipped through the grid and was visible between the grid and the beam surface. Errors were not counted if the animal was not making a forward movement or when the animal’s head was oriented to the left or right of the beam. Error per step scores, number of steps, and time to traverse the beam were calculated for saline and 6-OHDA-treated mice. Median data across the five trials were calculated.

2.3.5. Adhesive Removal

The adhesive removal test was adapted from studies in rats [29, 53] and in genetic PD mouse models [46, 48, 49, 51]. Prior to surgery, two training trials were performed by placing adhesive dots (0.6cm diameter, Avery) on the plantar surface of both forelimbs simultaneously. Training was used to acclimate the mice to the sensory stimuli (adhesive dots), which decreases their anxiolytic responses during the testing sessions post-surgery. At 3 weeks after 6-OHDA or saline injections, adhesive dots were placed on both forelimbs and the time to remove the dot from each forelimb was recorded (Supplementary Video 5a, 5b). If a mouse did not remove either or both stickers within 60 seconds, the animal received a score of 60 (seconds) for the respective forelimb(s). Median data were calculated across three trials.

2.3.6 Adjusting Steps (Stepping) Test

The adjusting steps test was adapted from studies in rats [54–57] and MPTP-treated mice [58] and impairment in this test was reversed by pharmacological replacement of dopamine in MPTP mice [58]. Mice were held by the base of the tail with their hindlimbs suspended above the table and moved backwards at a steady rate so that they traversed 1 meter distance over about 3 to 4 seconds. The mice were video-recorded, during this movement, (Supplementary Video 6a, 6b) and the video was analyzed offline by counting the number of adjusting steps made with the contralateral or ipsilateral paw relative to the injected hemisphere over the total distance. Five trials were performed on mice at 3 weeks after surgery and median data were calculated across the trials.

2.3.7 Pole test

The pole test has been used to detect bradykinesia and motor coordination in PD mice [46, 48, 50, 59–61]. Behavioral deficits in the pole test have been ameliorated by dopamine agonist treatment in MPTP mice [59, 61] and in a Parkinsonian genetic mouse model [50]. The mice were placed facing upwards at the top of a wooden pole (50 cm long and 1 cm in diameter) that led into their home cage. The mice were trained, in two sessions on consecutive days before 6-OHDA or saline injections, to turn to orient downward and traverse the pole into their homecage. At 3 weeks after surgery, the mice were tested for the amount of time to turn to orient downward and the total time to descend the pole from the time that the animal is placed on the pole until it reaches the base of the pole in the homecage (Supplementary Video 7a, 7b). Five trials were performed with each mouse and median data were taken across the trials. Times were limited to 60 seconds.

2.3.8 Spontaneous Activity

The spontaneous activity test was adapted from the limb-use asymmetry test [29] [46, 48, 50, 51]. Behavioral impairments in this test were shown to be reversed by treatment with dopamine agonists in a Parkinsonian genetic mouse model [50]. A transparent cylinder (15.5cm in height and 12.7cm in diameter) was placed on a piece of glass and a mirror was angled below the cylinder to visualize stepping movement from underneath and overall movement from all directions. The right hindlimb was marked in order to distinguish left from right steps. Sessions were video taped for 3 min (Supplementary Video 8a, 8b) and scored offline to evaluate the number of steps taken by each limb (contralateral and ipsilateral, forelimb and hindlimb) and the total number of rearing movements. A ratio of contralateral–to–ipsilateral steps was calculated for the forelimbs and hindlimbs.

2.4 Tyrosine hydroxylase staining and quantification

At 3 or 9 weeks after 6-OHDA surgeries, mice were deeply anesthetized and then transcardially perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in phosphate buffered saline (PBS). The brains were removed from the skull and post-fixed for 1–2 hours in 4% PFA in PBS, or overnight if insufficient fixation was achieved from perfusion. Brain tissue sections (50μm) were cut on a vibrating microtome (Leica VT1000S). Sections containing the SNc were incubated with primary anti-TH antibody (1:5000, Sigma) for 24–48 hours at 4°C, followed by secondary horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated antibody (1:500; Jackson Laboratories) for 2 hours at room temperature, and then developed by a reaction with diaminobenzidine (DAB) (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). The sections were then dehydrated, counterstained with Cresyl Violet, and mounted with Permount (Fischer Scientific). Sections containing the striatum were incubated with anti-TH antibody at the same conditions, followed by Cy3 conjugated antibody (1:300, Jackson Laboratories) and mounted with Mowiol (Polysciences). SNc DAB stained sections were imaged with Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.). Striatal immunofluorescent sections were imaged using the Tissue FAXS system (Tissue Gnostics, Inc.) on the Zeiss Axio ImagerZ1 (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc).

Striatal TH-immunoreactive fibers were quantified in Fiji (NIH) using the mean intensity values obtained from the striata and cortices according to [10]. The relative optical density (OD), arbitrary units (AU), of the striatum was determined by subtracting the mean intensity of the cortex from the mean intensity of the ipsilateral striatum and averaging these values for two separate sections from the same animal. The percent of striatal denervation was determined by comparing the relative mean intensity values between the injected and uninjected hemispheres.

2.5 Statistics

Nonparametric, Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare between 6-OHDA and saline-treated mice due to the relatively small sample sizes of the experimental groups (n=5–9). All data are presented as medians ± ranges. All statistical analyses were performed using Prism (Graph Pad Software, Inc.) and p<0.05 was set as the level of significance.

3. Results

3.1 Anatomical verification of 6-OHDA lesions in mice

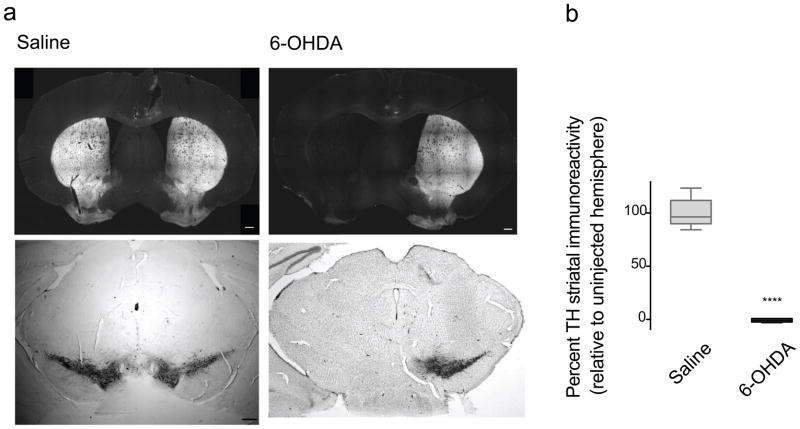

Stereotaxic unilateral injections of 6-OHDA (2.5mg/ml) in the MFB in mice produced a near complete ablation of SNc dopaminergic neurons in the injected hemisphere, as determined by the marked loss of TH-positive neurons (Fig 1a, Supplementary Fig 1) and a near complete loss (>90% in all mice) of TH-positive striatal fibers in the injected hemisphere relative to the uninjected hemisphere (Fig 1 and Supplementary Fig 2), which confirms the near complete lesion of the ipsilateral nigrostriatal pathway. On the other hand, saline MFB injections produced no obvious loss of SNc TH-positive neurons (Fig 1, Supplementary Fig 1) or striatal terminal fibers (Fig 1 and Supplementary Fig 2).

Fig 1.

Unilateral 6-OHDA injections produced a near complete loss of dopaminergic, TH-immunoreactive nigrostriatal neurons at 9 weeks after lesion. a) Representative sections from a 6-OHDA injected mouse (right) showed a dramatic loss of TH-immunoreactive striatal terminal fibers (top) and SNc neurons (bottom) in the lesioned hemisphere compared to normal TH immunostaining in a saline injected mouse (left). b) Quantification of the TH striatal denervation showed a significant decrease (**** p<0.0001, Mann Whitney) in the percentage of TH-immunoreactive striatal terminal fibers in the injected hemisphere, relative to the uninjected hemisphere, in 6-OHDA-injected mice (n=15) compared to saline-injected mice (n=11). Data are presented as median ± ranges. Scale bar = 300μm.

3.2 Behavioral tests

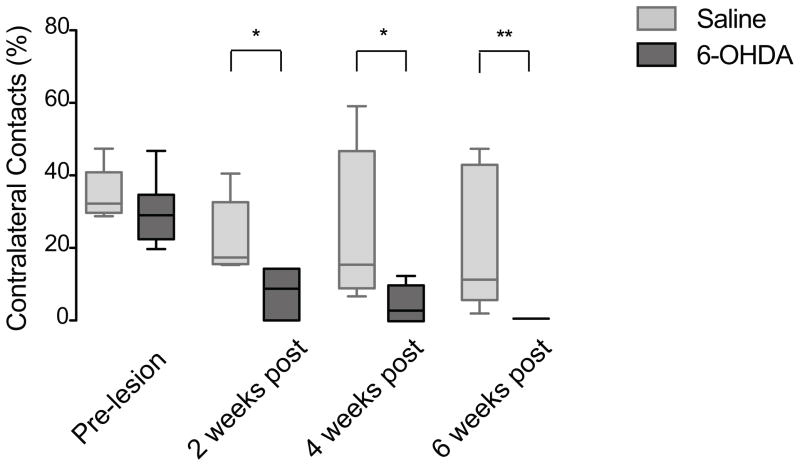

In the first set of behavioral experiments, we assessed sensorimotor behavior in 6-OHDA-lesioned and saline-injected mice using the limb-use asymmetry test and two tests for gait impairment. The limb-use asymmetry (cylinder) test, which measures weight-bearing forelimb movements during rearing (see Materials and Methods), was previously shown to be a good indicator of nigrostriatal cell loss in unilateral 6-OHDA injected rats and mice [29, 30, 40, 47]. Similar to previous studies, 6-OHDA-injected mice exhibited a significant decrease in the percentage of contralateral forelimb (the impaired forepaw) placements at 2, 4, and 6 weeks after surgery compared to saline-injected mice (Fig 2) (p<0.01, p<0.05, and p<0.01, respectively; Mann Whitney). These data confirm that the forelimb asymmetry test is a reliable and reproducible indicator of forelimb motor impairment in unilateral 6-OHDA MFB injected mice.

Fig 2.

The limb-use asymmetry (cylinder) test. 6-OHDA-lesioned mice (n=6) showed a significant decrease in the percentage of contralateral contacts at 2 weeks (** p=0.0078), 4 weeks (* p=0.0341), and 6 weeks (** p=0.0039) post surgery compared to saline-injected mice (n=5). Data are presented as median ± ranges.

Next, we compared the effectiveness of two different gait analysis paradigms: the automated treadmill test and the traditional manual paw-inking test. Manual assessment of gait parameters is typically done from footprints made by mice running freely through a tunnel on a piece of paper after their paws are colored [31, 45–48, 62]. The manual gait analysis was used previously to reveal alterations in stride length and stride width in several rodent models of PD, including MPTP-lesioned mice and 6-OHDA-lesioned mice and rats [33, 43, 45, 47, 62–65]. The automated DigiGait treadmill apparatus (Mouse Specifics, Inc.) was developed to provide a better control for variability in the animal’s speed of running and to offer an automated analysis of a large number of gait parameters [41, 43, 65–67].

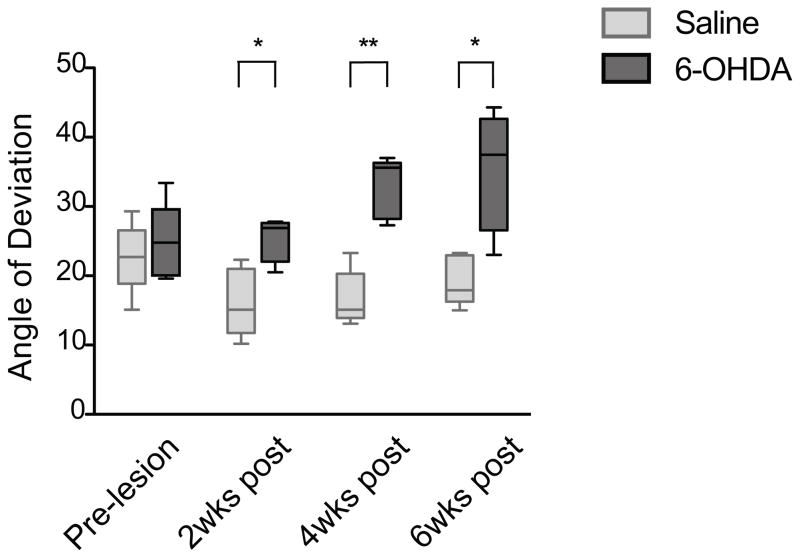

The same group of mice tested by the limb-use asymmetry test was also tested with the DigiGait treadmill apparatus for automated gait analysis. The 6-OHDA-lesioned mice showed a significant increase in the paw placement angle of the contralateral hindlimb compared to saline-treated mice at 2, 4 and 6 weeks after 6-OHDA injection (Fig 3) (p<0.05, p<0.01, and p<0.05, respectively, Mann Whitney). However, there was no consistent difference in any of the other 34 parameters measured, including the stride length, stride width, stride frequency, and stride length variability (Supplementary Fig 3). This was surprising, since alterations in stride length and stride width have been reported in 6-OHDA-lesioned mice and rats using the traditional paw-inking method [47, 63, 64].

Fig 3.

Gait analysis using the DigiGait treadmill apparatus. 6-OHDA-lesioned mice (n=5) showed a significant increase in the contralateral hindpaw angle of deviation at 2 weeks (* p=0.0317), 4 weeks (** p=0.0079) and 6 weeks (* p=0.0317) post lesion compared to saline-injected mice (n=5). Data are presented as median ± ranges.

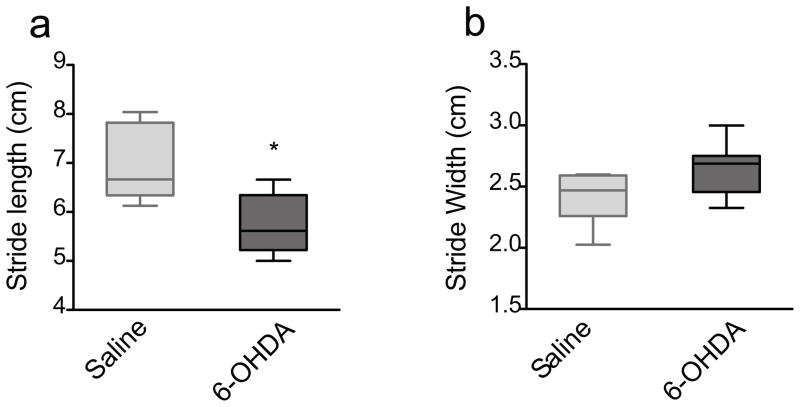

To reconcile the differences between our DigiGait results and published paw-inking data in 6-OHDA animals, we assessed stride length and stride width in a new group of saline- and 6-OHDA-injected mice at 3 weeks after surgery using the manual paw-inking method. The 3-week time-point was chosen for this and subsequent experiments based on the limb-use asymmetry results, which demonstrated motor deficits already at 2 weeks, which persisted at 4 and 6 weeks, post-surgery (Fig 2). 6-OHDA-treated mice displayed a significant decrease in stride length (p<0.05, Mann Whitney) (Fig 4a), but only a trend towards an increase in stride width (p=0.0675, Mann-Whitney), compared to saline-treated mice (Fig 4b). The paw-inking method thus seemed more reliable, not to mentioned simpler, compared to the automated treadmill test. Nevertheless, the gait data were overall more variable compared to other sensorimotor tests used in this study (see below and Discussion).

Fig 4.

The manual gait test. 6-OHDA-lesioned mice (n=9) exhibited a) a significant decrease in the average stride length (* p=0.036) but b) no difference in the average stride width (p=0.0675) at 3 weeks post lesion compared to saline-treated mice (n=6). Data are presented as median ± ranges.

Next, we used a group of sensorimotor behavioral tests that were not previously applied in the unilateral 6-OHDA mouse model: the challenging beam, adhesive removal, adjusting steps, pole, and spontaneous activity tests. These tests were evaluated in control (saline-injected) and lesioned mice at 3 weeks after saline or 6-OHDA injection.

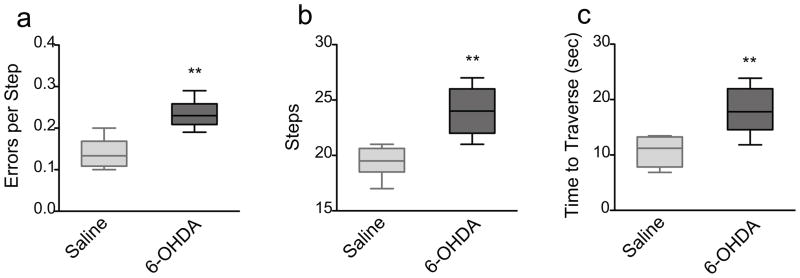

The challenging beam test assesses skilled walking and overall motor coordination of the mouse as it traverses a progressively narrowing beam leading into its home cage. 6-OHDA-lesioned mice showed a highly significant increase in the number of errors per step (p<0.005, Mann Whitney), the total number of steps (p<0.005, Mann Whitney), as well as the time it took to traverse the beam (Mann Whitney; p<0.005) compared to saline-treated mice (Fig 5a–c).

Fig 5.

The challenging beam test. 6-OHDA-lesioned mice (n=9) showed a significant decrease in a) errors per step (** p=0.0032), b) number of steps (** p=0.0021) and c) total time to traverse the beam (** p=0.0028) at 3 weeks post lesion compared to saline animals (n=6). Data are presented as median ± ranges.

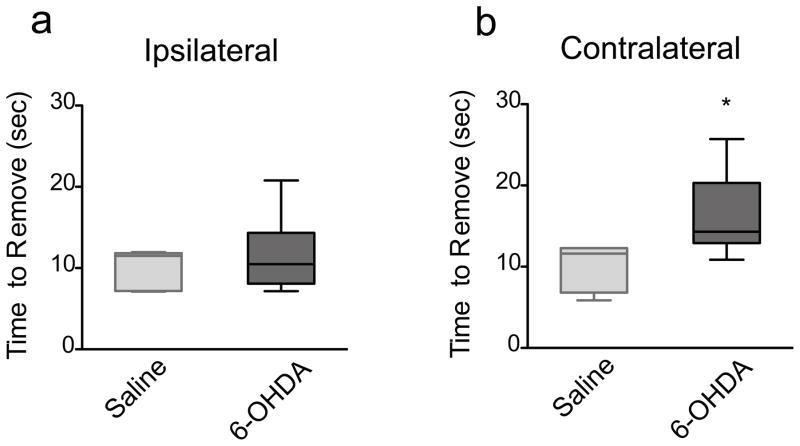

The adhesive removal test measures the time to remove sensory stimuli (adhesives) placed on each forepaw. 6-OHDA-lesioned mice showed no difference in the time to remove the adhesive on the ipsilateral (unimpaired) side (p=0.8596, Mann Whitney) compared to saline-injected mice (Fig 6a). However, 6-OHDA-lesioned mice exhibited a significant increase in the removal time on the contralateral (impaired) side (p=0.0214, Mann Whitney) compared to saline-injected mice (Fig 6b).

Fig 6.

The adhesive removal test. a) 6-OHDA-lesioned mice (n=6) showed no difference in the time to remove the adhesive on the ipsilateral side (p=0.8596) at 3 weeks post lesion compared to saline-injected mice (n=4). b) 6-OHDA-lesioned mice showed a significant increase in the time to remove the adhesive on the contralateral side (* p=0.0214) at 3 weeks post lesion compared to saline-injected mice (n=4). Data are presented as median ± ranges.

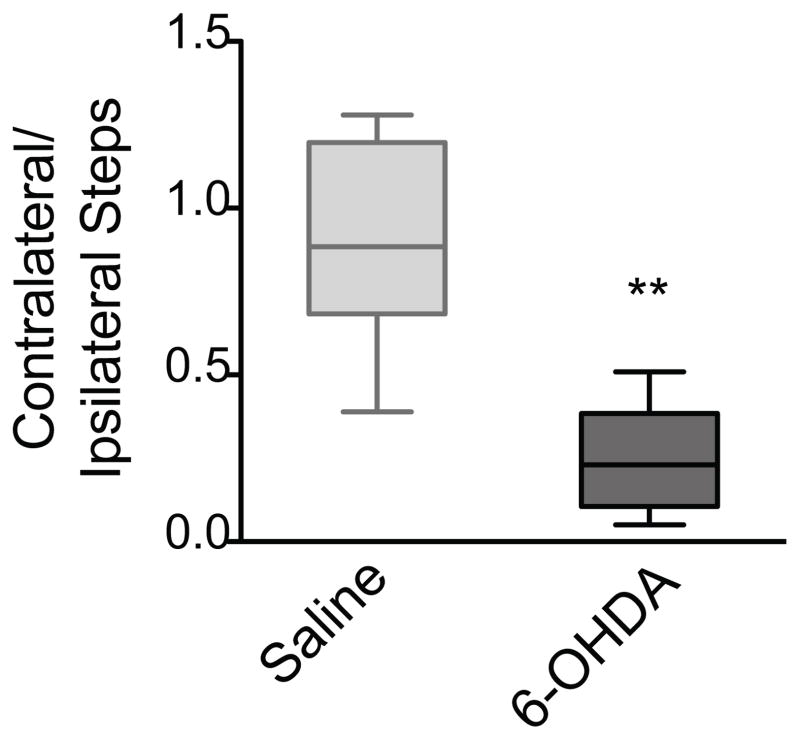

The adjusting steps test assesses the number of steps made by the contralateral and ipsilateral forepaws as the mouse is moved across a surface with its hindpaws elevated in the air. In our experiments, 6-OHDA-lesioned mice exhibited a strong preference for using the ipsilateral, unimpaired forepaw, as indicated by a highly significant decrease in the ratio of contralateral–to–ipsilateral steps compared to saline-injected mice (p<0.002, Mann Whitney). Conversely, saline-injected mice used both paws at equal proportions, as shown by a contralateral-to-ipsilateral ratio near one (Fig 7).

Fig 7.

The adjusting steps test. 6-OHDA-lesioned mice (n=9) showed a significant decrease (** p=0.0016) in the ratio of contralateral-to-ipsilateral forelimb adjusting steps taken at 3 weeks post lesion compared to saline-injected mice (n=6). Data are presented as median ± ranges.

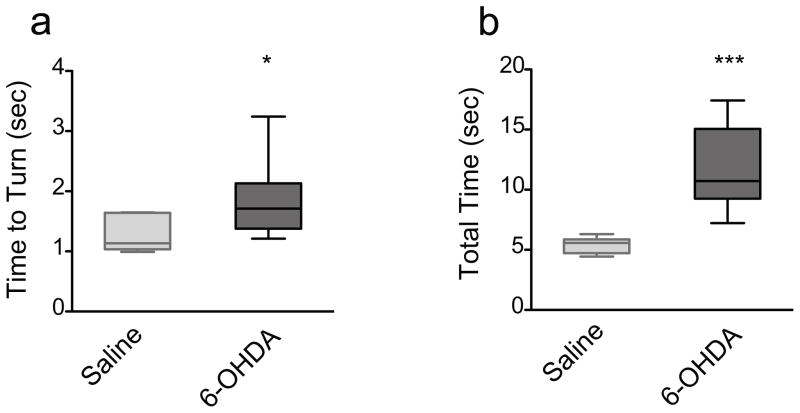

In the pole test, mice are placed on a wooden pole facing upwards and the time to turn to orient downward, as well as the total time to descend the pole, are recorded. 6-OHDA-lesioned mice showed a significant increase in the time to turn to orient downward (p<0.05, Mann Whitney) and a highly significant increase in the total time to traverse the pole (p<0.001, Mann Whitney) compared to saline-treated mice (Fig 8ab).

Fig 8.

The pole test. 6-OHDA-lesioned mice (n=9) displayed a significant increase in the a) time to turn and orient downward (left; * p=0.0256) as well as the b) total time to traverse the pole (right; *** p=0.0004) at 3 weeks post lesion relative to saline-injected mice (n=6). Data are presented as median ± ranges.

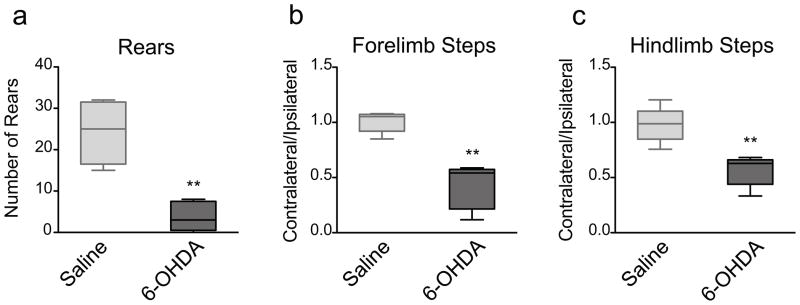

Finally, in the spontaneous activity test the mice are placed in a cylinder and their movements are scored for the total number of rearing movements and the number of steps taken by each paw (contralateral and ipsilateral; hindlimb and forelimb) in a 3-minute period. 6-OHDA-lesioned mice showed a highly significant decrease in the total number of rears (p<0.0079, Mann Whitney) (Fig 9a) and in the contralateral–to–ipsilateral forelimb step ratio (p<0.0079, Mann Whitney) and hindblimb step ratio (p<0.0079, Mann Whitney) compared to saline-injected mice (Fig 9b).

Fig 9.

The spontaneous activity test. 6-OHDA-lesioned mice (n=9) exhibited a significant decrease in a) the total number of rears (** p=0.0079), b) the contralateral-to-ipsilateral forelimb steps ratio (** p=0.0079), and c) the contralateral-to-ipsilateral hindlimb steps ratio (** p=0.0079) at 3 weeks post lesion compared to saline-injected mice (n=4). Data are presented as median ± ranges.

4. Discussion

The present study evaluates eight sensorimotor tests in the unilateral 6-OHDA mouse model of PD. In general, there are two scenarios in which sensorimotor behavioral tests are used in PD research. First, studies focusing on the underlying mechanisms in PD, such as electrophysiological studies of cellular or circuit functions in brain slices prepared from 6-OHDA-lesioned mice [11, 68–71], need to reliably verify that the mouse is well lesioned before performing the experiments. In that situation, it is desirable to have one, or at most two, simple tests that can quickly distinguish animals with incomplete lesions. Conversely, studies that focus on testing therapeutic approaches typically use multiple behavioral tests to carefully evaluate sensorimotor improvements. In this scenario, given the somatotopic organization of the basal ganglia [72–74], it is particularly important to use a variety of behavioral tests that assess different sensorimotor skills.

Which tests included in our study may be best suited for simple and reliable validation of 6-OHDA lesioned mice? Since the 6-OHDA MFB injections caused a dramatic and reproducible loss of nigrostriatal dopaminergic innervation in all lesioned mice, as demonstrated by a near complete loss of anti-TH immunoreactivity, we would expect to detect highly significant behavioral differences between lesioned and control mice. Based on the obtained p-values, our data suggest that the following behavioral tests were especially robust in distinguishing between 6-OHDA-lesioned and control mice: the adjusting steps test (p=0.0016), the challenging beam test (p≤ 0.0032 for all parameters), the pole test (total time to traverse p=0.0004), the spontaneous activity test (p=0.0079 for all parameters), and the limb-use asymmetry test (p=0.0078). We suggest that from these tests, the adjusting steps test and the limb-use asymmetry tests are both simple paradigms that detect highly significant behavioral impairments without any need for pre-training of the animals. The spontaneous activity test is another highly significant test however it requires a modest time investment for behavioral scoring. The challenging beam and pole tests both require pre-training of the animals and therefore may be better suited as part of a battery of behavioral tests (see below).

In contrast to the consistency of the tests discussed above, we found more variability in the results obtained from the gait analysis tests. The manual paw-inking test showed a modest difference in the stride length (p=0.036) and failed to detect a difference in the stride width (p = 0.0675) between lesioned and control mice. Even though the stride width difference may become statistical significant in a larger dataset than the current group of 9 lesioned and 6 saline-injected mice [45, 63], our results suggest that the manual gait measure is not a reliable readout for the selection of individual lesioned versus non-lesioned mice. The automated gait analysis by the DigiGait treadmill was even less reliable than the manual gait testing, as we failed to detect any reproducible impairment in over 30 measured gait parameters with the exception of the hindlimb paw placement angle. These results agree with a previous study in MPTP-lesioned mice that found a change in stride length by manual paw-inking, but not with the DigiGait treadmill analysis [62]. Taken together, the treadmill gait analysis appears the least useful from the tests included in our study for scoring motor performance in the 6-OHDA mouse model.

The use of a battery of behavioral tests that score motor behaviors is particularly important for testing therapeutic approaches in various PD mouse models [20–22, 75], as well as for characterizing genetic mouse models engineered to carry mutations identified in PD patients [34–36]. Given the range of motor impairments in PD patients [1, 2], it is essential that the assessment of potential treatment options and the study of genetic PD models include accurate tests that can assay multiple aspects of sensorimotor function. The following behavioral tests used in this study can reliably detect a range of behaviors related to motor symptoms seen in PD patients including: the adjusting steps test and the limb-use asymmetry test for scoring akinesia-related deficits, the pole test (total time to traverse) for bradykinesia, the manual gait test and the spontaneous activity test for gait patterns, and the challenging beam and the pole test for general motor coordination. Our study thus demonstrates a battery of drug-free behavioral tests that can be performed with PD mouse models in a wide range of research studies without the need for expensive equipment and with only limited pre-training of animals. Additionally, the adjusting steps, limb-use asymmetry, and spontaneous movement tests all reliably detected unilateral deficits in the impaired vs. the unimpaired side of the body, which makes these tests particularly relevant for scoring behavioral impairment in unilateral 6-OHDA-injected mice.

The dorsolateral striatum (putamen in primates) contains an extensive somatotopic organization of overlapping cortical somatosensory and motor inputs in rodents and primates [76], and this region also shows the largest degree of a loss of dopaminergic innervation in PD patients [77, 78]. A comparison between hindlimb and forelimb movements may be a particularly good readout for detecting somatotopy in the rodent brain, since hindlimbs were found to be represented dorsally and forelimbs ventrally within the lateral striatum [79]. Several behavioral tests used in our study detected highly specific forelimb impairments including: the adjusting steps, limb-use asymmetry and spontaneous activity tests. For hindlimb-specific tasks, we found highly significant sensorimotor impairments using the spontaneous activity test, but only a modest hindlimb impairment in stride length with the manual gait test. The hindlimb paw placement angle was also greatly increased in 6-OHDA lesioned mice in the automated treadmill gait analysis, but this was the only positive measure in the treadmill scoring. Taken together, these results suggest that either hindlimb-specific deficits are less pronounced in the unilateral 6-OHDA mouse model or most of the tests that we used are less sensitive to detect them compared to forelimb-specific deficits in this mouse model. Since the MFB 6-OHDA injections produced consistent, near complete unilateral lesions of the nigrostriatal system, it seems unlikely that the modest hindlimb deficits were due to insufficient lesions of relevant somatotopic striatal regions. In the future, it may therefore be important to develop additional sensorimotor tests that specifically target hindlimb impairment for testing in 6-OHDA-lesion and other PD mouse models to fully determine the extent of hindlimb deficit in 6-OHDA lesion mice compared other PD mouse models.

Sensorimotor impairment following 6-OHDA MFB injections in rodents has traditionally been associated with the loss of nigrostriatal dopaminergic cells. However, previous studies utilizing 6-OHDA MFB lesions in mice [47, 80] and rats [10, 64, 81] have also reported a marked loss of TH immunoreactivity in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and the nucleus accumbens, in addition to the SNc. In agreement with these studies, we also saw a substantial loss of TH immunoreactivity in the VTA and the nucleus accumbens (Fig 1, Supplementary Figs 1–2). Therefore, our findings, together with previous studies, suggest that behavioral studies utilizing the MFB lesion model must consider the potential effect of combined dopaminergic cell loss in the SNc, VTA and nucleus accumbens in the manifestation of the sensorimotor behavioral impairments.

5. Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that the limb-use asymmetry, challenging beam, pole test, adjusting steps, and spontaneous activity tests are all highly sensitive assays to assay a variety of sensorimotor impairments in the unilateral 6-OHDA MFB injected mouse model, including akinesia, bradykinesia, and motor incoordination. This battery of sensorimotor tests can used to 1) characterize the extent of lesion in 6-OHDA-injected mice and 2) assess the effectiveness of potential therapeutic approaches in the 6-OHDA mouse model.

Supplementary Material

Research Highlights.

Behavioral assessment of 6-OHDA treated mice.

Battery of eight sensorimotor tests.

Limb-use asymmetry, challenging beam, pole, adjusting steps, and spontaneous activity tests are highly robust behavioral tests.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Mark Bevan, Dr. C. Savio Chan, and Dr. Richard J. Miller for helpful discussions, Yu Chen and Cassandra Shum for excellent technical assistance, Kai Fan and Dr. Mark Bevan for help with immunohistochemistry quantification, John Linardakis for assistance with the DigiGait apparatus, and David Klein for assistance with 6-OHDA surgeries. This work was supported by grants from the Michael J Fox Foundation to P.O. and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NS047085 and NS041234) to D.J.S., and by the Northwestern University Cell Imaging Facility and a Cancer Center Support Grant (NCI CA060553).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lees AJ, Hardy J, Revesz T. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 2009;373:2055–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60492-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dauer W, Przedborski S. Parkinson’s disease: mechanisms and models. Neuron. 2003;39:889–909. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00568-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.George JL, Mok S, Moses D, Wilkins S, Bush AI, Cherny RA, et al. Targeting the progression of Parkinson’s disease. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2009;7:9–36. doi: 10.2174/157015909787602814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Surmeier DJ, Guzman JN, Sanchez-Padilla J, Goldberg JA. What causes the death of dopaminergic neurons in Parkinson’s disease? Prog Brain Res. 2010;183:59–77. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(10)83004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beal MF. Experimental models of Parkinson’s disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:325–34. doi: 10.1038/35072550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meredith GE, Kang UJ. Behavioral models of Parkinson’s disease in rodents: a new look at an old problem. Mov Disord. 2006;21:1595–606. doi: 10.1002/mds.21010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bezard E, Przedborski S. A tale on animal models of Parkinson’s Disease. Mov Disord. 2011;26:993–1002. doi: 10.1002/mds.23696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bove J, Prou D, Perier C, Przedborski S. Toxin-induced models of Parkinson’s disease. NeuroRx. 2005;2:484–94. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.2.3.484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thoenen H, Tranzer JP. The pharmacology of 6-hydroxydopamine. Annu Rev Pharmacol. 1973;13:169–80. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.13.040173.001125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuan H, Sarre S, Ebinger G, Michotte Y. Histological, behavioural and neurochemical evaluation of medial forebrain bundle and striatal 6-OHDA lesions as rat models of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci Methods. 2005;144:35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Day M, Wang Z, Ding J, An X, Ingham CA, Shering AF, et al. Selective elimination of glutamatergic synapses on striatopallidal neurons in Parkinson disease models. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:251–9. doi: 10.1038/nn1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magill PJ, Bolam JP, Bevan MD. Dopamine regulates the impact of the cerebral cortex on the subthalamic nucleus-globus pallidus network. Neuroscience. 2001;106:313–30. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00281-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerfen CR, Engber TM, Mahan LC, Susel Z, Chase TN, Monsma FJ, Jr, et al. D1 and D2 dopamine receptor-regulated gene expression of striatonigral and striatopallidal neurons. Science. 1990;250:1429–32. doi: 10.1126/science.2147780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zigmond MJ, Acheson AL, Stachowiak MK, Stricker EM. Neurochemical compensation after nigrostriatal bundle injury in an animal model of preclinical parkinsonism. Arch Neurol. 1984;41:856–61. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1984.04050190062015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hassani OK, Mouroux M, Feger J. Increased subthalamic neuronal activity after nigral dopaminergic lesion independent of disinhibition via the globus pallidus. Neuroscience. 1996;72:105–15. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00535-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glinka Y, Gassen M, Youdim MB. Mechanism of 6-hydroxydopamine neurotoxicity. J Neural Transm Suppl. 1997;50:55–66. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6842-4_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi LH, Woodward DJ, Luo F, Anstrom K, Schallert T, Chang JY. High-frequency stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus reverses limb-use asymmetry in rats with unilateral 6-hydroxydopamine lesions. Brain Res. 2004;1013:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fang X, Sugiyama K, Akamine S, Namba H. Improvements in motor behavioral tests during deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus in rats with different degrees of unilateral parkinsonism. Brain Res. 2006;1120:202–10. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.08.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meissner W, Harnack D, Paul G, Reum T, Sohr R, Morgenstern R, et al. Deep brain stimulation of subthalamic neurons increases striatal dopamine metabolism and induces contralateral circling in freely moving 6-hydroxydopamine-lesioned rats. Neurosci Lett. 2002;328:105–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00463-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo J, Kaplitt MG, Fitzsimons HL, Zuzga DS, Liu Y, Oshinsky ML, et al. Subthalamic GAD gene therapy in a Parkinson’s disease rat model. Science. 2002;298:425–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1074549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanchez-Pernaute R, Harvey-White J, Cunningham J, Bankiewicz KS. Functional effect of adeno-associated virus mediated gene transfer of aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase into the striatum of 6-OHDA-lesioned rats. Mol Ther. 2001;4:324–30. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2001.0466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Azzouz M, Martin-Rendon E, Barber RD, Mitrophanous KA, Carter EE, Rohll JB, et al. Multicistronic lentiviral vector-mediated striatal gene transfer of aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase, tyrosine hydroxylase, and GTP cyclohydrolase I induces sustained transgene expression, dopamine production, and functional improvement in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10302–12. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10302.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laganiere J, Kells AP, Lai JT, Guschin D, Paschon DE, Meng X, et al. An engineered zinc finger protein activator of the endogenous glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor gene provides functional neuroprotection in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci. 2010;30:16469–74. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2440-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harms AS, Barnum CJ, Ruhn KA, Varghese S, Trevino I, Blesch A, et al. Delayed dominant-negative TNF gene therapy halts progressive loss of nigral dopaminergic neurons in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Mol Ther. 2011;19:46–52. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dowd E, Monville C, Torres EM, Wong LF, Azzouz M, Mazarakis ND, et al. Lentivector-mediated delivery of GDNF protects complex motor functions relevant to human Parkinsonism in a rat lesion model. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:2587–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ungerstedt U, Arbuthnott GW. Quantitative recording of rotational behavior in rats after 6-hydroxy-dopamine lesions of the nigrostriatal dopamine system. Brain Res. 1970;24:485–93. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(70)90187-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robinson TE, Kolb B. Structural plasticity associated with exposure to drugs of abuse. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47(Suppl 1):33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fleckenstein AE, Hanson GR. Impact of psychostimulants on vesicular monoamine transporter function. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;479:283–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.08.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schallert T, Fleming SM, Leasure JL, Tillerson JL, Bland ST. CNS plasticity and assessment of forelimb sensorimotor outcome in unilateral rat models of stroke, cortical ablation, parkinsonism and spinal cord injury. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:777–87. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tillerson JL, Cohen AD, Philhower J, Miller GW, Zigmond MJ, Schallert T. Forced limb-use effects on the behavioral and neurochemical effects of 6-hydroxydopamine. J Neurosci. 2001;21:4427–35. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-12-04427.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fleming SM. Behavioral outcome measures for the assessment of sensorimotor function in animal models of movement disorders. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2009;89:57–65. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(09)89003-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allbutt HN, Henderson JM. Use of the narrow beam test in the rat, 6-hydroxydopamine model of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci Methods. 2007;159:195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schallert T, Whishaw IQ, Ramirez VD, Teitelbaum P. Compulsive, abnormal walking caused by anticholinergics in akinetic, 6-hydroxydopamine-treated rats. Science. 1978;199:1461–3. doi: 10.1126/science.564552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dawson TM, Ko HS, Dawson VL. Genetic animal models of Parkinson’s disease. Neuron. 2010;66:646–61. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fleming SM, Fernagut PO, Chesselet MF. Genetic mouse models of parkinsonism: strengths and limitations. NeuroRx. 2005;2:495–503. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.2.3.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Magen I, Chesselet MF. Genetic mouse models of Parkinson’s disease The state of the art. Prog Brain Res. 2010;184:53–87. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(10)84004-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Valjent E, Bertran-Gonzalez J, Herve D, Fisone G, Girault JA. Looking BAC at striatal signaling: cell-specific analysis in new transgenic mice. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:538–47. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cetin A, Komai S, Eliava M, Seeburg PH, Osten P. Stereotaxic gene delivery in the rodent brain. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:3166–73. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Francardo V, Recchia A, Popovic N, Andersson D, Nissbrandt H, Cenci MA. Impact of the lesion procedure on the profiles of motor impairment and molecular responsiveness to L-DOPA in the 6-hydroxydopamine mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;42:327–40. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lundblad M, Picconi B, Lindgren H, Cenci MA. A model of L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia in 6-hydroxydopamine lesioned mice: relation to motor and cellular parameters of nigrostriatal function. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;16:110–23. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hampton TG, Stasko MR, Kale A, Amende I, Costa AC. Gait dynamics in trisomic mice: quantitative neurological traits of Down syndrome. Physiol Behav. 2004;82:381–9. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tillerson JL, Miller GW. Grid performance test to measure behavioral impairment in the MPTP-treated-mouse model of parkinsonism. J Neurosci Methods. 2003;123:189–200. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(02)00360-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amende I, Kale A, McCue S, Glazier S, Morgan JP, Hampton TG. Gait dynamics in mouse models of Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2005;2:20. doi: 10.1186/1743-0003-2-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tillerson JL, Caudle WM, Reveron ME, Miller GW. Detection of behavioral impairments correlated to neurochemical deficits in mice treated with moderate doses of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine. Exp Neurol. 2002;178:80–90. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.8021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fernagut PO, Diguet E, Labattu B, Tison F. A simple method to measure stride length as an index of nigrostriatal dysfunction in mice. J Neurosci Methods. 2002;113:123–30. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(01)00485-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fleming SM, Salcedo J, Fernagut PO, Rockenstein E, Masliah E, Levine MS, et al. Early and progressive sensorimotor anomalies in mice overexpressing wild-type human alpha-synuclein. J Neurosci. 2004;24:9434–40. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3080-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iancu R, Mohapel P, Brundin P, Paul G. Behavioral characterization of a unilateral 6-OHDA-lesion model of Parkinson’s disease in mice. Behav Brain Res. 2005;162:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fleming SM, Chesselet MF. Behavioral phenotypes and pharmacology in genetic mouse models of Parkinsonism. Behav Pharmacol. 2006;17:383–91. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200609000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goldberg MS, Fleming SM, Palacino JJ, Cepeda C, Lam HA, Bhatnagar A, et al. Parkin-deficient mice exhibit nigrostriatal deficits but not loss of dopaminergic neurons. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:43628–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308947200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hwang DY, Fleming SM, Ardayfio P, Moran-Gates T, Kim H, Tarazi FI, et al. 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine reverses the motor deficits in Pitx3-deficient aphakia mice: behavioral characterization of a novel genetic model of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2132–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3718-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lu XH, Fleming SM, Meurers B, Ackerson LC, Mortazavi F, Lo V, et al. Bacterial artificial chromosome transgenic mice expressing a truncated mutant parkin exhibit age-dependent hypokinetic motor deficits, dopaminergic neuron degeneration, and accumulation of proteinase K-resistant alpha-synuclein. J Neurosci. 2009;29:1962–76. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5351-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fleming SM, Salcedo J, Hutson CB, Rockenstein E, Masliah E, Levine MS, et al. Behavioral effects of dopaminergic agonists in transgenic mice overexpressing human wildtype alpha-synuclein. Neuroscience. 2006;142:1245–53. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fleming SM, Delville Y, Schallert T. An intermittent, controlled-rate, slow progressive degeneration model of Parkinson’s disease: antiparkinson effects of Sinemet and protective effects of methylphenidate. Behav Brain Res. 2005;156:201–13. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chang JW, Wachtel SR, Young D, Kang UJ. Biochemical and anatomical characterization of forepaw adjusting steps in rat models of Parkinson’s disease: studies on medial forebrain bundle and striatal lesions. Neuroscience. 1999;88:617–28. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00217-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Olsson M, Nikkhah G, Bentlage C, Bjorklund A. Forelimb akinesia in the rat Parkinson model: differential effects of dopamine agonists and nigral transplants as assessed by a new stepping test. J Neurosci. 1995;15:3863–75. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-03863.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schallert T, De Ryck M, Whishaw IQ, Ramirez VD, Teitelbaum P. Excessive bracing reactions and their control by atropine and L-DOPA in an animal analog of Parkinsonism. Exp Neurol. 1979;64:33–43. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(79)90003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lindner MD, Winn SR, Baetge EE, Hammang JP, Gentile FT, Doherty E, et al. Implantation of encapsulated catecholamine and GDNF-producing cells in rats with unilateral dopamine depletions and parkinsonian symptoms. Exp Neurol. 1995;132:62–76. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(95)90059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Blume SR, Cass DK, Tseng KY. Stepping test in mice: a reliable approach in determining forelimb akinesia in MPTP-induced Parkinsonism. Exp Neurol. 2009;219:208–11. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ogawa N, Hirose Y, Ohara S, Ono T, Watanabe Y. A simple quantitative bradykinesia test in MPTP-treated mice. Res Commun Chem Pathol Pharmacol. 1985;50:435–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Singh B, Wilson JH, Vasavada HH, Guo Z, Allore HG, Zeiss CJ. Motor deficits and altered striatal gene expression in aphakia (ak) mice. Brain Res. 2007;1185:283–92. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Matsuura K, Kabuto H, Makino H, Ogawa N. Pole test is a useful method for evaluating the mouse movement disorder caused by striatal dopamine depletion. J Neurosci Methods. 1997;73:45–8. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(96)02211-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Guillot TS, Asress SA, Richardson JR, Glass JD, Miller GW. Treadmill gait analysis does not detect motor deficits in animal models of Parkinson’s disease or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Mot Behav. 2008;40:568–77. doi: 10.3200/JMBR.40.6.568-577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hsieh TH, Chen JJ, Chen LH, Chiang PT, Lee HY. Time-course gait analysis of hemiparkinsonian rats following 6-hydroxydopamine lesion. Behav Brain Res. 2011;222:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Klein A, Wessolleck J, Papazoglou A, Metz GA, Nikkhah G. Walking pattern analysis after unilateral 6-OHDA lesion and transplantation of foetal dopaminergic progenitor cells in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2009;199:317–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kurz MJ, Pothakos K, Jamaluddin S, Scott-Pandorf M, Arellano C, Lau YS. A chronic mouse model of Parkinson’s disease has a reduced gait pattern certainty. Neurosci Lett. 2007;429:39–42. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.09.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wooley CM, Sher RB, Kale A, Frankel WN, Cox GA, Seburn KL. Gait analysis detects early changes in transgenic SOD1(G93A) mice. Muscle Nerve. 2005;32:43–50. doi: 10.1002/mus.20228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Goldberg NR, Hampton T, McCue S, Kale A, Meshul CK. Profiling changes in gait dynamics resulting from progressive 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-induced nigrostriatal lesioning. J Neurosci Res. 2011 doi: 10.1002/jnr.22699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chan CS, Glajch KE, Gertler TS, Guzman JN, Mercer JN, Lewis AS, et al. HCN channelopathy in external globus pallidus neurons in models of Parkinson’s disease. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:85–92. doi: 10.1038/nn.2692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Taverna S, Ilijic E, Surmeier DJ. Recurrent collateral connections of striatal medium spiny neurons are disrupted in models of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci. 2008;28:5504–12. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5493-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shen W, Tian X, Day M, Ulrich S, Tkatch T, Nathanson NM, et al. Cholinergic modulation of Kir2 channels selectively elevates dendritic excitability in striatopallidal neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1458–66. doi: 10.1038/nn1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kravitz AV, Freeze BS, Parker PR, Kay K, Thwin MT, Deisseroth K, et al. Regulation of parkinsonian motor behaviours by optogenetic control of basal ganglia circuitry. Nature. 2010;466:622–6. doi: 10.1038/nature09159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nambu A, Tokuno H, Takada M. Functional significance of the cortico-subthalamo-pallidal ‘hyperdirect’ pathway. Neurosci Res. 2002;43:111–7. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(02)00027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Obeso JA, Rodriguez-Oroz MC, Benitez-Temino B, Blesa FJ, Guridi J, Marin C, et al. Functional organization of the basal ganglia: therapeutic implications for Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2008;23(Suppl 3):S548–59. doi: 10.1002/mds.22062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Parent A, Hazrati LN. Functional anatomy of the basal ganglia. I. The cortico-basal ganglia-thalamo-cortical loop. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1995;20:91–127. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(94)00007-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Duty S, Jenner P. Animal models of Parkinson’s disease: a source of novel treatments and clues to the cause of the disease. Br J Pharmacol. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01426.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.McGeorge AJ, Faull RL. The organization of the projection from the cerebral cortex to the striatum in the rat. Neuroscience. 1989;29:503–37. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90128-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bernheimer H, Birkmayer W, Hornykiewicz O, Jellinger K, Seitelberger F. Brain dopamine and the syndromes of Parkinson and Huntington. Clinical, morphological and neurochemical correlations. J Neurol Sci. 1973;20:415–55. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(73)90175-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nambu A. Somatotopic organization of the primate Basal Ganglia. Front Neuroanat. 2011;5:26. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2011.00026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cho J, West MO. Distributions of single neurons related to body parts in the lateral striatum of the rat. Brain Res. 1997;756:241–6. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00143-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Grealish S, Mattsson B, Draxler P, Bjorklund A. Characterisation of behavioural and neurodegenerative changes induced by intranigral 6-hydroxydopamine lesions in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;31:2266–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kirik D, Rosenblad C, Bjorklund A. Characterization of behavioral and neurodegenerative changes following partial lesions of the nigrostriatal dopamine system induced by intrastriatal 6-hydroxydopamine in the rat. Exp Neurol. 1998;152:259–77. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1998.6848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.