Abstract

Computational image analysis is used in many areas of biological and medical research, but advanced techniques including machine learning remain underutilized. Here, we used automated segmentation and shape analyses, with pre-defined features and with computer generated components, to compare nuclei from various premature aging disorders caused by alterations in nuclear proteins. We considered cells from patients with Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS) with an altered nucleoskeletal protein; a mouse model of XFE progeroid syndrome caused by a deficiency of ERCC1-XPF DNA repair nuclease; and patients with Werner syndrome (WS) lacking a functional WRN exonuclease and helicase protein. Using feature space analysis, including circularity, eccentricity, and solidity, we found that XFE nuclei were larger and significantly more elongated than control nuclei. HGPS nuclei were smaller and rounder than the control nuclei with features suggesting small bumps. WS nuclei did not show any significant shape changes from control. We also performed principle component analysis (PCA) and a geometric, contour based metric. PCA allowed direct visualization of morphological changes in diseased nuclei, whereas standard, feature-based approaches required pre-defined parameters and indirect interpretation of multiple parameters. Both methods yielded similar results, but PCA proves to be a powerful pre-analysis methodology for unknown systems.

Keywords: aging, feature space analysis, Hutchinson Gilford progeria syndrome, nuclear image analysis, principal component analysis, Werner syndrome, XFE progeroid syndrome

Introduction

Clinicians, histologists, biologists, and other researchers have used morphological information of different biological structures for diagnosis and mechanistic information. Specifically, nuclear morphology has played a significant role in cancer histology for decades.1,2 Recently, computational image analysis and machine learning techniques have been utilized to enhance diagnostic imaging.3 Computational analysis of nuclear features aids in diagnosis of cancer4-7 while highlighting cellular phenotypes that are characteristic of tumor cells.8-10 Characterization of nuclear morphological features may provide insights into mechanisms of diseases as well as in cellular development.11

Nuclear morphology changes in several tissues as organisms age.12,13 Furthermore, nuclear morphology abnormalities are common in progeria syndromes, which are diseases of accelerated aging. Examination of nuclear morphology may be used to examine progression of the disease14 and help to evaluate therapies.15 There are several premature aging disorders caused by mutations in nuclear proteins. Here, we study Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS), Werner syndrome (WS), and primary cells from Ercc1−/− mice that model XFE (xeroderma pigmentosum type F-ERCC1) progeroid syndrome.16 HGPS is a premature segmented aging syndrome caused by a mutation in LMNA, which codes for the nucleoskeletal structural proteins including lamin A and lamin C.17 Patients with HGPS develop symptoms by two years of age and show extensive systemic phenotypes including osteoporosis, osteoarthristis and cardiovascular disease, which ultimately causes death in the early teens.18 WS, also known as an adult progeria, is a premature aging syndrome caused by loss of the WRN helicase and exonuclease, critical for telomere function and replication stress.19 WS symptoms develop after puberty, patients look much older than their chronological age, and they die of cancer or heart disease in their late forties or early fifties.20 ERCC1-XPF is a structure-specific endonuclease involved in the repair of helix-distorting DNA lesions, interstrand crosslinks and some double-strand breaks.21-24 Mutations that cause reduced levels of ERCC1-XPF can result in either the skin cancer-prone disorder xeroderma pigmentosum (XP), cerebro-oculo-facio-skeletal syndrome or a disease of accelerated aging (progeria).16,25 Nuclei from patients with HGPS,26 WS27 and Ercc1−/− mice28 have all been reported to have altered morphology.

Although the molecular defects of these diseases are well-established, the mechanisms by which they lead to cellular phenotypes or systemic aging are poorly understood. At the nuclear level, morphological phenotypes are typically described qualitatively as “dysmorphic” or “blebbed” and are quantified in a binary fashion as the presence or absence of a particular characteristic, often scored by eye. Numerical, feature-based approaches (including size, circularity, eccentricity, etc.) quantify differences between forms by pre-defined numerical features.29 However, these features must be chosen ahead of time, and composite images are hard to reconstruct from these features. Here, we also view the entire shape as a morphological exemplar constructed in geometric space.30-32 In this approach, little or no information is lost and the entire image information can often be utilized for computation. Direct mapping from one form to another allows direct comparison of morphological changes. We applied a contour-based metric and principle component analysis to produce direct, visual comparisons of nuclear shapes between the three aging disorders.

In this study, we analyze nuclear shapes using large sample sizes, automated segmentation and computational analysis of nuclear images to compare and quantify changes in cells from progeria patients and mice to better understand nuclear dysmorphisms associated with accelerated aging. Ultimately, the characterization of nuclear deformation in premature aging diseases may enable diagnosis or classification of newly identified aging disorders by simple comparison with an image database. High throughput analysis of nuclear shapes characteristic of the disease may provide a quantitative endpoint for screening therapeutic drugs or measuring disease progression. Also, we may be able to suggest mechanisms of cellular aging based on monitoring progressive nuclear structural changes associated with these diseases.

Results

Feature space analysis (FSA)

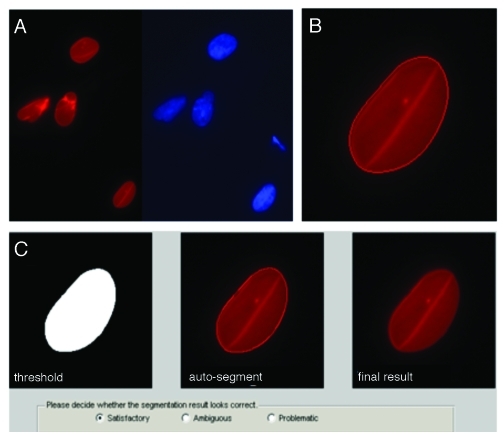

The sample size for each group was dependent on the number of images available and segmentation quality. We used an automated segmentation process, which did not bias segmentation to the human eye and significantly reduced analysis time to under 1 h for hundreds of images (see Methods). User input was only used to confirm the segmentation of each image to avoid overlapping nuclei or blurred images (see Methods from Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Automated pre-processing of nuclear images. (A) Raw images were collected with multiple fluorescence channels (see methods): red and blue channels for Lamin A/C and DNA, respectively. (B) Matlab code segmented the Lamin A/C channel using a level set active contour algorithm to delineate individual borders; here, after 320 iterations. (C) The code then showed the raw and computed nuclear image and allowed input from user to adjust the contour manually by dilating and eroding. Multiple views of the segmented nucleus (left to right: binary segmentation, segmentation with an outline and the result after segmentation) allowed rapid visualization and the possibility for manual adjustment after the auto-segmentation. Pop-up boxes allowed user to confirm segmentations. Only satisfactory results were used for computation.

We first analyzed the images based on shape parameters, usually dimensionless, which were defined precisely. With our automated segmentation, we were able to perform rigorous FSA in relatively short time. This analysis was performed in the “feature space” since the features were pre-determined. Most commercial image analysis software programs perform feature space analysis (including Image J). With this methodology, dimensionless shape parameters are compared across many groups, but the actual dysmorphic shapes must be inferred from multiple features.

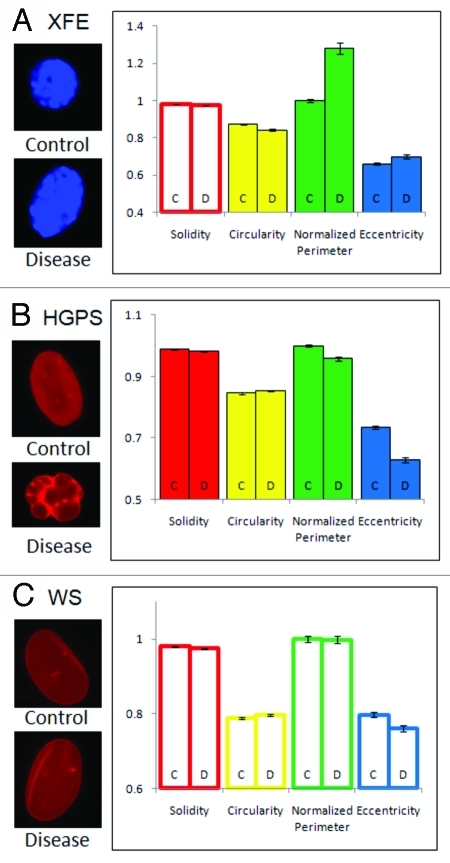

In cells from Ercc1−/− murine model of XFE progeroid syndrome, circularity, perimeter and eccentricity of the nuclei were statistically different from control cells from a normal littermate, but solidity was similar to the control (Fig. 2A). On average, XFE nuclei were more elongated and had a greater perimeter than their control set. Since the increase in perimeter was much greater than the difference in elongation, an increased perimeter may be partly from an increase in size, as well as from elongation.

Figure 2. Feature space analysis of nuclei in aging disorders. Segmented nuclei were analyzed for shape factors (Table 2), and perimeter was normalized to the average perimeter of the corresponding control group. (C and D) indicate control and disease groups, respectively. Bars are color-coded by the parameters. Solid bars indicate that the control and disease groups are statistically different, and outlined bars indicate that they are statistically similar based on a confidence of p < 0.01. The error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Representative images of each group are shown on the left of the graph, all to scale. (A) Nuclei in cells from the Ercc1−/− mice, a model of XPE, showed altered circularity, perimeter and eccentricity. (B) HGPS patient cell nuclei at passage 22 showed differences in all features. (C) WS cell nuclei showed no differences to control nuclei.

Nuclei in cells cultured from HGPS patients were less solid, less elongated, more circular and had a smaller perimeter (Fig. 2B). Based on these results, HGPS nuclei were smaller, invaginated, and rounder than the control group. HGPS nuclei were more likely to have many small blebs rather than a few big ones, but the difference in perimeter was greater than the difference in solidity, indicating that a large number of small blebs significantly increase the perimeter without adding much concave area.

In comparison to the nuclei of Ercc1−/− mice and HGPS patients, nuclei from patients with WS did not exhibit any noticeable differences from the corresponding control nuclei (Fig. 2C). While WS is an aging disorder associated with nuclear abnormalities, it did not cause a statistically significant deformation in the nucleus, according to the FSA of large numbers of nuclei.

As we examined feature space shape parameters of XFE and HGPS cells, we observed that the control groups of these diseases were similar to one another. Although the sizes (normalized perimeter) of the control nuclei were significantly different due to species differences (mouse vs. human cells), other parameters of the control groups had statistically similar values. However, each disorder was completely unique in its deformation: XFE nuclei were characterized by elongation and increase in size, HGPS nuclei were characterized by multiple small blebs, which caused the nuclei to be smaller and rounder.

Geometric approach and principle component analysis (PCA)

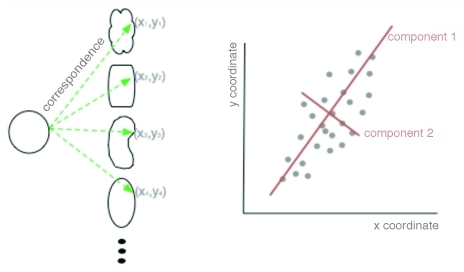

The FSA described above has been reproducibly used to obtain relevant biological information from image data, but it assumes that the chosen set of features includes information relevant to analyzing the data. An alternative is to use a geometry-based approach with the entire contour information from each nucleus obtained from the segmentation and pre-processing steps described above. Geometric analysis compares variation in coordinate locations, with respect to a reference set of coordinates (Fig. 3). First, for each segmented nuclear contour, all the points along this contour are converted to a polar coordinate system with respect to the center of mass, and points are sampled with equal angle intervals. Each nucleus in a set (including both disease and control) is thus defined by an (x,y) in the polar coordinate system (Fig. 3, left). The corresponding points in each contour are then averaged to produce a representative average shape (Fig. 4, left). The coordinates of all the nuclear contours (again, both disease and control) are then analyzed with respect to this average using principal component analysis (PCA).

Figure 3. Schematic of principal component analysis (PCA) in geometric space. Two dimensional shapes are assigned polar coordinates (x,y) so that many, disparate shapes can be statistically compared on one graph. From this graph, the principal components of variation can be determined by which lines best identify the largest variance of the data (red lines).

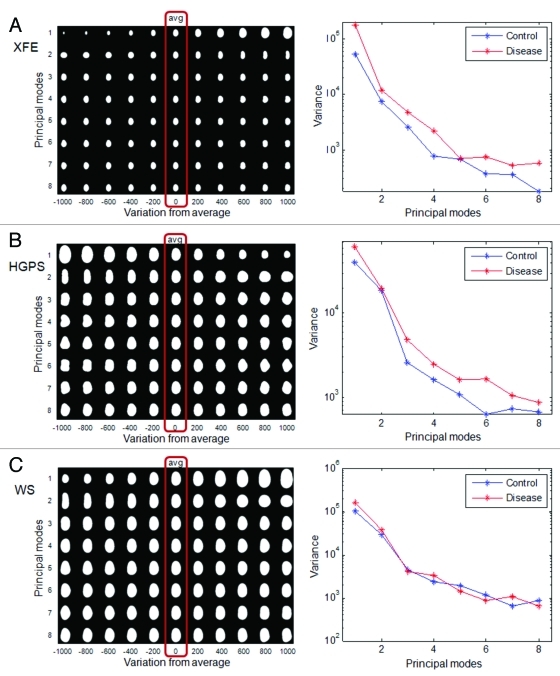

Figure 4. PCA of nuclei in aging disorders. Principal component analysis was performed on control and disease groups of each disease. The panels on the left show the average nuclear shape of both the disease and control groups (red box) and the first 8 modes of PCA for each group. The x-axis shows image variations from the average shape of the nuclei. The graphs on the right show the variance of the control and disease group from the average shape (x-axis) per mode (y-axis). (A) In XFE nuclei, the most significant deformation modes were size and elongation, and the disease group had greater variation; (B) HGPS nuclei showed higher variation and deformation modes of size and elongation, and modes with bumps; (C) WS control and disease groups has similar variations in all modes.

In PCA, the corresponding (x, y) coordinates are analyzed to extract the main modes of variation for each sample from the average (Fig. 3) simultaneously for all coordinates. The purpose of utilizing this approach is to derive 2-dimensional “features” relevant for analyzing the phenotypes based on the data itself rather than trying to use a priori assumptions as in FSA. The principle modes (i.e., main variations from the average) are computed from these 2-dimensional graphs (Fig. 3, right) by finding vectors which best represent the data (Fig. 3, red lines). The degree of variation from the average, along the bisecting line, is used to quantify the degree of shape change, called the variance. Each principal variation from the average can be quantified to understand the main modes of variation present in the data (Fig. 4, left). The significant modes of variation can then be analyzed for their significance in finding a statistically significant difference between two sets of nuclei, the control and the disease. To that end, each nuclear contour is “projected” onto the direction, and the standard Student t-test can be used to measure significance between two groups. The benefit of this system is that multi-dimensional parameters can be added to the machine-learned sorting including fluorescence intensities and distributions of intensities. The algorithm is able to determine the metrics of sorting as well as when information is not sufficiently different to allow statistical certainty of the sorting.

PCA analysis of nuclei

To determine PCA of nuclei, as described above, the control and disease nuclei of each group were first analyzed together to provide an average nuclear shape (Fig. 4, red box around the averages). XFE, HGPS and WS nuclei, as well as their control analogs, all had similar average elliptical shapes with one pole slightly narrower than another, like an egg. The similarity in average nuclear shape may reflect that all cell types were fibroblasts, and the average shape of WS and HGPS were the most similar because they were both human fibroblasts. The PCA technique was then applied to show how the data set differs from the average. The first 8 modes of deformation typically were able to provide features describing how the sample group varied from the average shape. These modes were determined from two-dimensional shape variations calculated from every shape in the data set, and there is no pre-processing bias. In many cases the differences appear small, but the statistical difference is provided by the algorithm. We can comment qualitatively on the modes, but exact features cannot be interpreted from the shapes. This variance from the average was different for the average and control samples (Fig. 4), and the distribution of shapes within this modal set was different in control and diseased nuclei (Fig. 5).

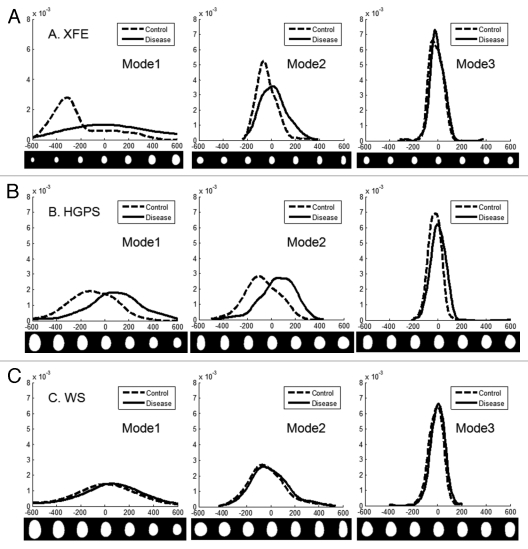

Figure 5. Comparison of control and disease group using PCA. The distribution of control and disease groups in the first three modes of PCA is shown. The x-axis represents the variation from the average, and the corresponding nuclear shape is shown below the x-axis. The y-axis represents the frequency of occurrence. (A) The XFE disease group was statistically larger (Mode 1) and more elongated (Mode 2) and had greater variation (width of the distributions); (B) the HGPS disease group was rounder and slightly more variant; (C) the WS disease and control groups were very similar.

In XFE nuclei, the disease group showed more variation in shape than the corresponding control group (Fig. 4A), suggesting altered nuclear shape could be a hallmark of the disease, possibly due to division defects. The first mode, related to size, suggested that the control group is both smaller and of more regular size than the disease group. This heterogeneity of size for XFE agreed with the FSA result, which was shown by higher standard error for all parameters. The second mode illustrated an elongation from the normal to the diseased nuclei but no thinning, similar to FSA. For modes greater than three, there was no significant difference between the disease and control groups (Fig. 5A).

Similar to XFE, the diseased group of HGPS showed a greater variance than the control group (Fig. 4B). The first mode suggested that the disease group is smaller and rounder. The second mode confirmed that the control group was more elongated. However, this mode did not also include differences in size, as it had in XFE. In the third mode, slight blebbing and invaginations were seen in the disease group (Fig. 5B). In WS, there was no significant difference between the control and the disease group in any modes or variance (Figs. 4C and 5C). This result agreed with the FSA results.

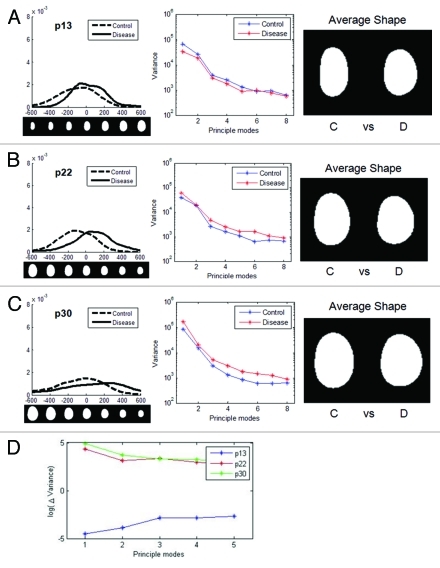

Passage dependence of HGPS cells

The abnormal nuclear phenotypes of HGPS fibroblasts become most obvious at late passages.14,26,33 To investigate changes in morphology over passage number in HGPS nuclei, we analyzed HGPS nuclei at three different passages (p13, p22 and p30). The general trend was that diseased nuclei were smaller and rounder than normal nuclei. In examining the first mode of each passage group, the control and diseased nuclei were similar at passage 13 (Fig. 6A) but showed significant deviation at the passage 22 (Figs. 6B and C). By passage 30, there was little change from passage 22 (Figs. 5and6D). However, at late passages control nuclei were also showing variance. We were able to take this into account, but in FSA there is no way to “subtract out” changes associated with altered control morphology with increased passage number.

Figure 6. Changes in nuclear shape in cells from HGPS patients with increasing passage. Shapes of HGPS nuclei were compared for multiple passages. For each passage, the distribution of nuclei in the first mode, variances of the first 8 modes, and average shapes of control and disease groups are shown, respectively. The nuclear images are to scale. (A) At early passage (p13), there was some variation between the control (C) and disease (D) group. (B) At passage 22, the difference became larger. (C) At late passage (p30) there were still differences between control and disease, but the control cell nuclei began to show greater cell-to-cell variability. (D) The difference in variance between the control and disease groups for the three passages (ΔVariance = Variance disease – Variance control) show a similarity for passage 22 and 30, which are significantly different than passage 13.

Numerous passages produced more dysmorphic behavior both in the HGPS cells and their controls. We calculated Δvariance, the difference between the disease and the control variances, for the first 8 modes (i.e., if the variance of the control is greater than the variance of the disease, Δvariance is negative). At early passage, the control group varied more. This could be because the HGPS nuclei only had a small number of dysmorphic nuclei at early passage. The averaging process of PCA among hundreds of images could not easily detect subtle and complex deformation. For later passages, the disease group had greater variance (Fig. 6D). For the first few modes, the late passage had the largest Δvariance.

Discussion

Automated image analysis and comparison of methods

Here we used automated segmentation and both feature space analysis and geometric analysis with PCA to compare differences among HGPS and WS patient cells, along with cells from the Ercc1 knockout mouse model of accelerated aging. Segmentation enabled quick analysis of large sets of data through an automated process but still allowed manual correction to ensure the quality of segmentation. The quality of segmentation was dependent upon the quality of imaging and preparation. However, the high-throughput methodology may also produce bias in the system. The segmentation program was less likely to provide satisfactory results for complicated boundaries, and complex images may have been discarded. Also, large sample size resulted in small standard errors for samples, but severe minority events may have been lost. For example, nuclei from HGPS patients can show dramatic outward blebbing and dilation,26 but these events are a very small percent of nuclei. Thus, there is a benefit to both visualization by eye and high throughout analysis.

There are several successful methods for analyzing the geometry of cellular shapes developed over the past two decades including point-based principal component analysis (the method we use), independent component analysis, Fourier descriptors, and several others.34 Generally, no method is superior for nuclear shape,34 so we chose PCA for simplicity and wide popularity in shape analysis from other biomedical applications including radiography. We analyzed the segmented nuclear shapes by the broadly used FSA as well as contour-based geometric approach. By using multiple cell types, the two methods to analyze nuclear morphology were directly compared and the advantages and disadvantages of the new contour-based imaging technique were determined. With a combination of contour-based geometric approach and PCA, shape changes were directly visualized from disease to control. We also computationally eliminated orientation and size differences and purely examined changes in nuclear morphology. However, the geometric approach was computationally intense, requiring a longer analysis time and more powerful hardware than FSA. Also, the contour-based approach with PCA was based on averaging shapes and gave results that were reflected in most dominant directions, so minor changes were not reflected. For example, features of the nuclear blebs associated with HGPS14,26,33 were not well captured with geometric analysis. PCA results are also difficult to compare with other published work without raw data.

Conversely, geometric analysis is well suited to be used in pre-analysis situations where visualization of average shapes and deviations of morphology may be useful to motivate further analysis. For example, an automated segmentation and geometric analysis can be applied as a global diagnostic tool especially when combined with high throughput genomic studies such as for drug studies or cells from the International Knockout Mouse Consortium (IKMC). Also, geometric analysis has the potential to include integration of multiple features, such as lamin concentration and chromatin heterogeneity.35

Comparison of nuclei in three aging disorders

Two independent analytical techniques yielded similar conclusions regarding nuclear dysmorphology for cells from three distinct progeroid patients or mice and their matched controls. Nuclei of primary Ercc1−/− fibroblasts, from a mouse model of XFE progeroid syndrome, were similar in size to the control nuclei but were statistically elongated. This may reflect stiffening or reorganizing of the DNA inside cells, reminiscent of the hemoglobin polymerization and red cell sickeling observed in sickle cell disorder. Loss of ERCC in mice results in reduced repair of DNA crosslinks, which may result in a global change in nucleoplasmic stiffness. Growing primary fibroblasts at 20% O2 induces cellular senescence.36 Hence the nuclear morphologic changes observed in Ercc1−/− fibroblasts were likely characteristic of senescent cells and could offer a rapid screening endpoint for quantifying senescent cells.

HGPS nuclei were smaller and rounder. This morphological change could be related to the over-accumulation of lamin proteins which causes a lamina-dominated shape which is in equilibrium as a spheroid. Interestingly, nuclei from patients with WS, which is caused by loss of a functional DNA helicase, showed no statistical difference from the control. This suggests that the nuclear changes associated with altered helicase function do not affect global nuclear structure sufficiently to be detected by morphological imaging. However, we examined early passage cells in this study and it was possible that more divergence between and control and WS cellular nuclei might be observed with increasing passage, as we reported for HGPS nuclei. Consistent with this, patients with WS develop premature aging features later in life compared with the Ercc1−/− mice, XFE progeroid syndrome patients, and patients with HGPS.20

Materials and Methods

HGPS and WS cell culture

The HGPS and control cells were human dermal fibroblasts HGADFN167 and HGADFN168, respectively, obtained from the Progeria Research Foundation at passage 9. HGADFN167 was taken from 8.5-y-old male patient, and HGADFN 168 was taken from the 40.5-y-old father of HGADFN167. The fibroblasts were cultured in Dulbecco's Modification of Eagles Medium (DMEM; Invitrogen 11960–044) with 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 2 mmol L-glutamine per foundation protocol.

The WS and control cells were human dermal fibroblasts AG00780 and AG11747, respectively, obtained from the Coriell Institute Cell Repository. AG00780 was from a male donor with confirmed C1336T mutations in both WRN alleles leading to a truncated protein lacking helicase activity. The control AG11747 cells were from a normal male donor. Both WS and control cell lines were from cultures that underwent a minimal number of population doublings, 8 and 16, respectively. Culture media and conditions were similar to the HGPS cell lines.

Ercc1−/− primary cells

Ercc1−/− primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts were generated from day 12 to 15 embryos produced from crossing inbred C57BL/6 mice heterozygous for Ercc1 null allele and genotyped by PCR, both described previously.16,37 The cells were grown in F10 and DMEM (1:1) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 5% CO2. At passage 5, the cells were plated on glass coverslips at a density of 2.5 x 104. The following day, the cells were fixed using 2% PFA for 10 min, rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and mounted with Vectashield with DAPI to label nuclei (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA).

Immunofluorescence

In preparation for imaging, the HGPS and WS cultured fibroblasts were fixed in 3.7% solution of formaldehyde in PBS, permeabilized with 0.2% solution of Triton-X 100 in PBS, and blocked using 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS. To label Lamin A/C, the fibroblasts were incubated in the primary antibody solution of 1:100 (mouse monoclonal IgG, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-7292) and then in the secondary solution of 1:200 (Alexa fluor 555 rabbit anti-mouse, Invitrogen). DNA was labeled using a 1:4000 1 mg/mL DAPI solution. The prepared cells were imaged on Leica DMI 6000B fluorescence Microscope at 63x (1.4 NA) and imaged with Leica DFC350 camera. Red and blue channels represented Lamin A/C and DNA, respectively.

Nuclear segmentation

Segmentation codes were developed in Matlab based on the semiautomatic method described elsewhere.35,38,39 Briefly, the random field graph cut method was used to obtain a rough contour, which incorporated both region and boundary information of the image. Then an efficient level set active contour algorithm38 was applied to refine the contours obtained via graph cut.35,40,41 Finally, the segmented results were reviewed manually. The segmented result could be manually adjusted by dilating and eroding, and the satisfactorily segmented nuclei were manually selected for the analysis (Fig. 1). Before the analysis, the images were pre-processed as in our previous works39 to eliminate variations due to arbitrary rotation, translation, and coordinate inversions of each nucleus. The procedure included normalization by the center of mass, rotation by major axis reorientation, and coordinate “flips” set up within a least squares minimization problem.

During this decision making process, 1–50% of the segmentation results were discarded, based primarily on the quality of sample preparation and imaging. Specifically, image quality is dependent on magnification and numerical aperture, focusing on the plane of the nucleus, and uniformity of the cells: most images have numerous nuclei per image and some may be out of focus. Labeling of the nucleoskeleton, including the lamins (as a rim-stain), also allowed better segmentation of nuclei. The useable sample sizes determined after the decision making process are listed in Table 1. In the feature space analysis, all satisfactory segmentation results were included. However, in the principal component analysis, the random subsets of images were chosen to maintain equal sample sizes for the control and disease groups as to not bias the distributions.

Table 1. Sample sizes used for analyses (number of nuclei).

| Feature Space Analysis | Principal Component Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

Control |

Disease |

Control |

Disease |

| XFE |

611 |

156 |

156 |

156 |

| HGPS |

315 |

303 |

303 |

303 |

| WS | 277 | 246 | 246 | 246 |

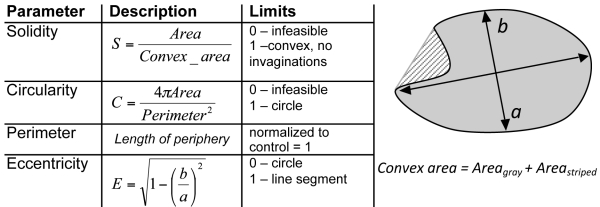

Feature space analysis

Segmented nuclear images were analyzed using a set of pre-programmed numerical features. The shape parameters used in the feature space analysis of this group of nuclei from aging disorders were solidity, circularity, normalized perimeter, and eccentricity. Definitions and equations of the parameters are listed in Table 2. The parameters were selected based on commonly used deformation modes in nuclear morphology.11,15,42 Features of the diseased group with the respective control were compared statistically using Student t-test unpaired with 2 tails. Samples with a Student t-test value of p < 0.01 were considered statistically different. More than 100 nuclei from at least 2 independent experiments, each, were pre-processed; an experiment is defined as independent fixation, labeling and imaging of cells within one passage of the replicate. No significant difference was noted between the analyzable nuclei from the independent experiments and data was combined. Samples were technical replicates since, for each disease type, only one disease cell line and one control cell line was imaged.

Table 2. Description of shape parameters defined by Matlab.

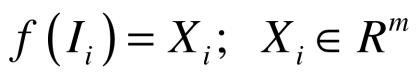

Geometric approach

Segmented images were also analyzed using a contour-based geometric approach43,44 to characterize the shape of the nuclei. As a result, each nucleus could be mapped to a point in a linear vector space  , where m is the dimension of the linear space (see Wang et al. 2011 for more details). The Principle Component Analysis (PCA) was applied to find the principle modes of variations for the data set. Nuclear images were analyzed by PCA to calculate deformation modes of the nuclei

, where m is the dimension of the linear space (see Wang et al. 2011 for more details). The Principle Component Analysis (PCA) was applied to find the principle modes of variations for the data set. Nuclear images were analyzed by PCA to calculate deformation modes of the nuclei  , and we also regenerated new samples to interpret the jth mode of variation in the data set including disease group and the control by

, and we also regenerated new samples to interpret the jth mode of variation in the data set including disease group and the control by  where

where  . By analyzing the data in this linear geometric space, we could visualize the principle modes of variation and interpret how data was distributed for different data set.

. By analyzing the data in this linear geometric space, we could visualize the principle modes of variation and interpret how data was distributed for different data set.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded partly by the NIH (ES0515052 to P.L.O., ES016114 to L.J.N. and S.Q.G., F30AG030905 to A.K. and GM088816 to G.K.R.), NSF (CBET-0954421 to K.N.D.) and the Progeria Research Foundation (to K.N.D.). S.C. wrote, refined and applied image analysis code and contributed to manuscript preparation. W.W. wrote and refined image analysis code and contributed to manuscript preparation. A.J.S.R. contributed to sample preparation, imaging, code refinement and manuscript preparation. A.K. contributed to sample preparation, imaging and manuscript preparation. S.Q.G. contributed to sample preparation, imaging and manuscript preparation. P.L.O. provided reagents and contributed to manuscript preparation. L.J.N. contributed to experimental design and manuscript preparation. G.K.R. wrote and refined image analysis code and contributed to manuscript preparation. K.N.D. oversaw the multiple PI project and contributed to manuscript preparation.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- FSA

feature space analysis

- HGPS

Hutchinson Gilford progeria syndrome

- WS

Werner syndrome

- PCA

principal component analysis

- XFE

XPF-ERCC1 progeroid syndrome

- XP

xeroderma pigmentosum

- XPF

xeroderma pigmentosum type F

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/nucleus/article/17798

References

- 1.Zink D, Fischer AH, Nickerson JA. Nuclear structure in cancer cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:677–87. doi: 10.1038/nrc1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Classes in oncology: George Nicholas Papanicolaou's new cancer diagnosis presented at the Third Race Betterment Conference, Battle Creek, Michigan, January 2-6, 1928, and published in the Proceedings of the Conference. CA Cancer J Clin. 1973;23:174–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duncan JS, Ayache N. Medical image analysis: Progress over two decades and the challenges ahead. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2000;22:85–106. doi: 10.1109/34.824822. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bacus JW. Cervical cell recognition and morphometric grading by image analysis. J Cell Biochem Suppl. 1995;23:33–42. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240590906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dawson AE, Austin RE, Jr., Weinberg DS. Nuclear grading of breast carcinoma by image analysis. Classification by multivariate and neural network analysis. Am J Clin Pathol. 1991;95:S29–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diamond DA, Berry SJ, Umbricht C, Jewett HJ, Coffey DS. Computerized Image-Analysis of Nuclear Shape as a Prognostic Factor for Prostatic-Cancer. Prostate. 1982;3:321–32. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990030402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elston CW, Ellis IO. Pathological Prognostic Factors in Breast-Cancer. 1. The Value of Histological Grade in Breast-Cancer - Experience from a Large Study with Long-Term Follow-Up. Histopathology. 1991;19:403–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1991.tb00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan HP, Doi K, Galhotra S, Vyborny CJ, MacMahon H, Jokich PM. Image feature analysis and computer-aided diagnosis in digital radiography. I. Automated detection of microcalcifications in mammography. Med Phys. 1987;14:538–48. doi: 10.1118/1.596065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green A, Martin N, Pfitzner J, O'Rourke M, Knight N. Computer image analysis in the diagnosis of melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:958–64. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(94)70264-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mangasarian OL, Street WN, Wolberg WH. Breast-Cancer Diagnosis and Prognosis Via Linear-Programming. Oper Res. 1995;43:570–7. doi: 10.1287/opre.43.4.570. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dahl KN, Ribeiro AJ, Lammerding J. Nuclear shape, mechanics, and mechanotransduction. Circ Res. 2008;102:1307–18. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.173989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maraldi NM, Mazzotti G, Rana R, Antonucci A, Di Primio R, Guidotti L. The nuclear envelope, human genetic diseases and ageing. Eur J Histochem. 2007;51(Suppl 1):117–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haithcock E, Dayani Y, Neufeld E, Zahand AJ, Feinstein N, Mattout A, et al. Age-related changes of nuclear architecture in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:16690–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506955102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verstraeten VL, Ji JY, Cummings KS, Lee RT, Lammerding J. Increased mechanosensitivity and nuclear stiffness in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria cells: effects of farnesyltransferase inhibitors. Aging Cell. 2008;7:383–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00382.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scaffidi P, Misteli T. Reversal of the cellular phenotype in the premature aging disease Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Nat Med. 2005;11:440–5. doi: 10.1038/nm1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niedernhofer LJ, Garinis GA, Raams A, Lalai AS, Robinson AR, Appeldoorn E, et al. A new progeroid syndrome reveals that genotoxic stress suppresses the somatotroph axis. Nature. 2006;444:1038–43. doi: 10.1038/nature05456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Sandre-Giovannoli A, Bernard R, Cau P, Navarro C, Amiel J, Boccaccio I, et al. Lamin a truncation in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria. Science. 2003;300:2055. doi: 10.1126/science.1084125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eriksson M, Brown WT, Gordon LB, Glynn MW, Singer J, Scott L, et al. Recurrent de novo point mutations in lamin A cause Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Nature. 2003;423:293–8. doi: 10.1038/nature01629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gray MD, Shen JC, Kamath-Loeb AS, Blank A, Sopher BL, Martin GM, et al. The Werner syndrome protein is a DNA helicase. Nat Genet. 1997;17:100–3. doi: 10.1038/ng0997-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang S, Lee L, Hanson NB, Lenaerts C, Hoehn H, Poot M, et al. The spectrum of WRN mutations in Werner syndrome patients. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:558–67. doi: 10.1002/humu.20337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuraoka I, Kobertz WR, Ariza RR, Biggerstaff M, Essigmann JM, Wood RD. Repair of an interstrand DNA cross-link initiated by ERCC1-XPF repair/recombination nuclease. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:26632–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000337200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahmad A, Robinson AR, Duensing A, van Drunen E, Beverloo HB, Weisberg DB, et al. ERCC1-XPF endonuclease facilitates DNA double-strand break repair. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:5082–92. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00293-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petit C, Sancar A. Nucleotide excision repair: from E. coli to man. Biochimie. 1999;81:15–25. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9084(99)80034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Niedernhofer LJ, Odijk H, Budzowska M, van Drunen E, Maas A, Theil AF, et al. The structure-specific endonuclease Ercc1-Xpf is required to resolve DNA interstrand cross-link-induced double-strand breaks. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5776–87. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.13.5776-5787.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jaspers NG, Raams A, Silengo MC, Wijgers N, Niedernhofer LJ, Robinson AR, et al. First reported patient with human ERCC1 deficiency has cerebro-oculo-facio-skeletal syndrome with a mild defect in nucleotide excision repair and severe developmental failure. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:457–66. doi: 10.1086/512486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldman RD, Shumaker DK, Erdos MR, Eriksson M, Goldman AE, Gordon LB, et al. Accumulation of mutant lamin A causes progressive changes in nuclear architecture in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8963–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402943101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adelfalk C, Scherthan H, Hirsch-Kauffmann M, Schweiger M. Nuclear deformation characterizes Werner syndrome cells. Cell Biol Int. 2005;29:1032–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McWhir J, Selfridge J, Harrison DJ, Squires S, Melton DW. Mice with DNA repair gene (ERCC-1) deficiency have elevated levels of p53, liver nuclear abnormalities and die before weaning. Nat Genet. 1993;5:217–24. doi: 10.1038/ng1193-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prewitt JM, Mendelsohn ML. The analysis of cell images. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1966;128:1035–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1965.tb11715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bookstein FL. The measurement of biological shape and shape change. Berlin; New York: Springer-Verlag, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller MI, Priebe CE, Qiu A, Fischl B, Kolasny A, Brown T, et al. Collaborative computational anatomy: an MRI morphometry study of the human brain via diffeomorphic metric mapping. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009;30:2132–41. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang W, Ozolek JA, Slepcev D, Lee AB, Chen C, Rohde GK. An optimal transportation approach for nuclear structure-based pathology. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2011;30:621–31. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2010.2089693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McClintock D, Gordon LB, Djabali K. Hutchinson-Gilford progeria mutant lamin A primarily targets human vascular cells as detected by an anti-Lamin A G608G antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2154–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511133103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pincus Z, Theriot JA. Comparison of quantitative methods for cell-shape analysis. J Microsc. 2007;227:140–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2007.01799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang W, Ozolek JA, Rohde GK. Detection and classification of thyroid follicular lesions based on nuclear structure from histopathology images. Cytometry A. 2010;77:485–94. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parrinello S, Samper E, Krtolica A, Goldstein J, Melov S, Campisi J. Oxygen sensitivity severely limits the replicative lifespan of murine fibroblasts. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:741–7. doi: 10.1038/ncb1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weeda G, Donker I, de Wit J, Morreau H, Janssens R, Vissers CJ, et al. Disruption of mouse ERCC1 results in a novel repair syndrome with growth failure, nuclear abnormalities and senescence. Curr Biol. 1997;7:427–39. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(06)00190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boyokov Y, Funka-Lea G. Graph cuts and efficient n-d image segmentation. Int J Comput Vis. 2006;70:109–31. doi: 10.1007/s11263-006-7934-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rohde GK, Ribeiro AJ, Dahl KN, Murphy RF. Deformation-based nuclear morphometry: capturing nuclear shape variation in HeLa cells. Cytometry A. 2008;73:341–50. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li C, Xu C, Gui C, Fox MD. Level set evolution without re- initialization: A new variational formulation. PROC CVPR IEEE. 2005;1:430–6. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li C, Huang R, Ding Z, Gatenby C, Metaxas D, Gore J. A variational level set approach to segmentation and bias correction of images with intensity inhomogeneity. Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv. 2008;11:1083–91. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-85990-1_130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Philip JT, Dahl KN. Nuclear mechanotransduction: response of the lamina to extracellular stress with implications in aging. J Biomech. 2008;41:3164–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wolfe P, Murphy J, McGinley J, Zhu Z, Jiang W, Gottschall EB, et al. Using nuclear morphometry to discriminate the tumorigenic potential of cells: a comparison of statistical methods. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:976–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang W, Mo Y, Ozolek JA, Rohde GK. Characterizing morphology differences from image data using a modified Fisher criterion. IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging. 2011:129–32. [Google Scholar]