Abstract

Summary: We describe handalign, a software package for Bayesian reconstruction of phylogenetic history. The underlying model of sequence evolution describes indels and substitutions. Alignments, trees and model parameters are all treated as jointly dependent random variables and sampled via Metropolis–Hastings Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC), enabling systematic statistical parameter inference and hypothesis testing. handalign implements several different MCMC proposal kernels, allows sampling from arbitrary target distributions via Hastings ratios, and uses standard file formats for trees, alignments and models.

Availability and Implementation: Installation and usage instructions are at http://biowiki.org/HandAlign

Contact: ihh@berkeley.edu

Supplementary information: Supplementary material is available at Bioinformatics online.

1 BACKGROUND

Multiple sequence alignments constitute a central part of many bioinformatics workflows. Commonly, an alignment is built from primary sequences, a tree is reconstructed from this alignment, and various analyses are run using the alignment and/or tree.

This can be problematic for several reasons. First, inference of the tree and alignment is likely to be uncertain: many alternative trees or alignments may explain the data comparably well. Downstream analyses that assume the tree and alignment to be true ignore this uncertainty, and potentially inherit embedded bias and error.

Second, this flow of information is circular: alignment algorithms often (implicitly or explicitly) make use of a guide tree, while tree- and model-fitting algorithms typically use an alignment as input. This leads to a chicken-and-egg situation.

In attempted resolution of these problems, the field of statistical alignment methods unifies alignment and tree-building as related inference tasks under a phylogenetic likelihood function. The handalign software is one such tool, building on a range of prior work in this area (Bouchard-Côté et al., 2009; Holmes and Bruno, 2001; Redelings and Suchard, 2005).

2 SAMPLING ALIGNMENTS, TREES AND PARAMETERS

handalign implements a Bayesian model of sequence phylogeny with separate substitution and indel components. To perform inference of unknown variables (i.e. trees, ancestral sequences or parameters) under this model, handalign makes use of Markov chain Monte Carlo sampling (MCMC). We cannot directly observe the indel history (H), tree (T) or evolutionary model parameters (θ). However, we can estimate their a posteriori probability distribution, conditional on what we do observe: the extant sequences (S). That is, we aim to sample (H, T, θ|S). Explicitly marginalizing H, T and θ is infeasibly expensive: there are combinatorially many trees T and histories H, and continuously varying parameters θ. MCMC provides a powerful alternative way to sample from (H, T, θ|S) that is often not much more expensive than computing the joint likelihood of (H, T, θ, S).

Informally, MCMC randomly walks the space of (H, T, θ) tuples, the number of steps spent at a particular tuple converging to the posterior probability P(H, T, θ|S). The result is a series {(Hn, Tn, θn)} of samples from the posterior.

Depending on the investigator's goals, various analyses can then be performed using the collection of tuples {(Hn, Tn, θn)}. The ensemble can be summarized with a single ‘consensus’ alignment or tree, including confidence levels (e.g. the probability that a given subset of species form a monophyletic clade, or that a given column is correct). Alternatively, downstream computations can be averaged over the ensemble: the sampled parameters can be used to estimate modes and moments (e.g. the most likely indel rate), or detect signatures of interest (e.g. positive selection).

As well as MCMC, handalign can perform a stochastic search using the same underlying model, but returning a single best-guess (H, T, θ) rather than a collection of such tuples.

3 CAPABILITIES

Given unaligned FASTA-format sequences, or (optionally) an ‘initial guess’ in the form of a Stockholm-format alignment with an embedded Newick-format tree. handalign performs N×|S| sampling steps (where |S| is the number of input sequences). Each step uses one of the MCMC kernel moves (described below) to update one of H, T or θ. If requested (via a command-line option), the new tuple (H, T, θ) is logged to a file. If operated in ‘Stochastic search’ mode, a greedy local search is performed every K samples to find the most likely nearby alignment. After N×|S| samples, the final (H, T, θ) tuple is output in Stockholm+Newick format.

Indel models: the insertion–deletion model is an affine-gap transducer approximation to a Long Indel birth-death process (Miklós et al., 2004) with insertion rate λ, deletion rate μ, deletion extension probability r. The approximation is that indel events never overlap on the same branch. Other indel length distributions, such as TKF91 or mixture-geometric, can be used.

Substitution models: any parametric continuous-time Markov chain can be used to model character evolution, via the file format of the companion program xrate. For instance, 20N-state amino acid models (with N-valued hidden states) and 64-state codon models have been used. Parameters of these substitution models can be sampled, allowing alignment-free estimation of statistics such as Ka/Ks. Ancestral characters are summed out(Holmes and Bruno, 2001); they can be imputed using xrate.

Tree prior: the prior over tree topologies is uniform, with a weak exponential prior over total branch length. Alternate priors can be implemented using the ‘Arbitrary target distribution’ mechanism.

Arbitrary target distribution: handalign allows any tree/alignment probability model to be implemented over a Unix pipe and used in a Metropolis–Hastings accept/reject step.

MCMC kernel moves: the relative proportions of the various sampling moves can be set on the command line. All are variants of Gibbs-sampling moves. Some are full Gibbs (perfectly mixing the sampled variables at every step); others utilize Metropolis-within-Gibbs or a variant of importance sampling that includes the current point in the list of accessible points. The individual moves vary in the dependence of their complexities on the input sequence length, L. The worst-case complexity with default settings is  (L2), comparable to BaliPhy (Redelings and Suchard, 2005).

(L2), comparable to BaliPhy (Redelings and Suchard, 2005).

Stochastic search: handalign can be used to do a partially randomized greedy search, yielding a relatively quick, approximate maximum likelihood estimate for the alignment and/or tree, in addition to a full MCMC trace. The iterative refinement command-line option interrupts the MCMC run periodically to perform a greedy (Viterbi) search for the locally maximal alignment close to the current sample.

Alignment banding: as the DP matrix may be costly to fill, both in time and memory, users may specify an alignment ‘band’ as a heuristic constraint. Command-line options can be used to prevent visiting cells more than M positions away from the current alignment path. This has the effect of causing indels longer than M to be excluded, but is otherwise ergodic, and generally converts an  (La) step into an

(La) step into an  (LMa−1) step (for a≥2).

(LMa−1) step (for a≥2).

HMMoC adapter: handalign can optionally make use of the Hidden Markov Model Compiler hmmoc to craft optimized C++ code for DP-based sampling steps. This typically speeds things up by a large constant factor.

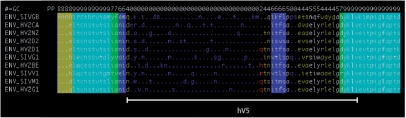

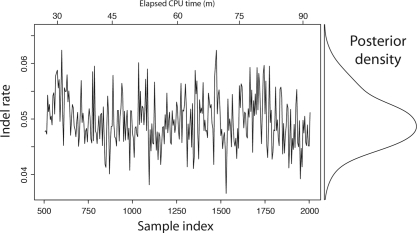

MCMC trace analysis: the DART package includes several scripts for summarizing MCMC traces. constock.pl finds a consensus alignment and uses ANSI terminal color to render posterior probabilities of individual columns (Fig. 1). Alternatively, trees can be extracted using stocktree.pl and a separate program, such as CONSENSE in the PHYLIP package, used to estimate consensus trees. handalign sampling traces use Stockholm alignment format to embed trees and parameters. A trace can be rendered as an ANSI terminal color animation using stockfilm.pl, converted into other common formats (see http://biowiki.org/StockholmTools) or the parameters extracted and their distribution analyzed (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

A summary alignment of SIV/HIV gp120 proteins produced by constock.pl. Posterior probabilities of alignment columns are shown on the ‘PP’ line (most significant decimal digit) and by ANSI terminal color (white-on-cyan is most reliable, blue-on-black is least). Hypervariable (hV) region 5 [Leonard et al. (1990)] corresponds with a low-confidence region.

Fig. 2.

The indel rate of the SIV/HIV gp120 protein has most of its probability mass concentrated between 0.04 and 0.06 indels per substitution. handalign was run for 90 min on a 3.4 GHz CPU, generating 2000 samples (500 discarded as burn-in). Every fifth sample is plotted; the entire trace was used to estimate the density.

Current limitations and performance: the  (L2) complexity may be limiting for longer sequences (e.g. genomes); alignment banding should ameliorate this (but its effect on mixing performance is untested). Underflow/precision issues may potentially be an issue with larger trees. A ongoing compilation of comparison tests is here: http://biowiki.org/HandAlignBenchmark

(L2) complexity may be limiting for longer sequences (e.g. genomes); alignment banding should ameliorate this (but its effect on mixing performance is untested). Underflow/precision issues may potentially be an issue with larger trees. A ongoing compilation of comparison tests is here: http://biowiki.org/HandAlignBenchmark

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Benjamin Redelings, Marc Suchard, Jotun Hein, Joe Herman, Alexandre Bouchard-Côté and many others working in statistical alignment for their illuminating discussions.

Funding: National Institutes of Health/National Human Genome Research Institute grant (R01-GM076705).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Footnotes

Note: References truncated to comply with page limit. See Supplementary Material for complete bibliography.

REFERENCES

- Bouchard-Côté A., et al. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 21 (NIPS) Vancouver, Canada: 2009. Efficient inference in phylogenetic InDel trees. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes I., Bruno W.J. Evolutionary HMMs: a Bayesian approach to multiple alignment. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:803–820. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.9.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard C., et al. Assignment of intrachain disulfide bonds and characterization of potential glycosylation sites of the type 1 recombinant human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein (gp120) expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. J. of Biol. Chem. 1990;265:10373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklós I., et al. A long indel model for evolutionary sequence alignment. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2004;21:529–540. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redelings B.D., Suchard M.A. Joint Bayesian estimation of alignment and phylogeny. Systematic Biol. 2005;54:401–418. doi: 10.1080/10635150590947041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.