Abstract

Motivation: To further our understanding of the mechanisms underlying biochemical pathways mathematical modelling is used. Since many parameter values are unknown they need to be estimated using experimental observations. The complexity of models necessary to describe biological pathways in combination with the limited amount of quantitative data results in large parameter uncertainty which propagates into model predictions. Therefore prediction uncertainty analysis is an important topic that needs to be addressed in Systems Biology modelling.

Results: We propose a strategy for model prediction uncertainty analysis by integrating profile likelihood analysis with Bayesian estimation. Our method is illustrated with an application to a model of the JAK-STAT signalling pathway. The analysis identified predictions on unobserved variables that could be made with a high level of confidence, despite that some parameters were non-identifiable.

Availability and implementation: Source code is available at: http://bmi.bmt.tue.nl/sysbio/software/pua.html.

Contact: j.vanlier@tue.nl

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Mathematical modelling is used to integrate hypotheses about a biochemical network in such a manner that such networks can be simulated. In addition to the formulation and testing of biochemical properties, computational models are used to predict unmeasured behaviour. Despite great advances in measurement techniques, the amount of data is still relatively scarce and therefore parameter uncertainty is an important research topic.

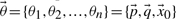

We focus on biochemical networks modelled using ordinary differential equations (ODEs). Such models consist of equations which contain parameters  , inputs

, inputs  and state variables

and state variables  . In many cases, these systems are only partially observed, which means that measurements

. In many cases, these systems are only partially observed, which means that measurements  are performed on a subset or a combination of the total number of states N in the model. This results in a mapping from an internal state to an output. Additionally, these measurements are hampered by noise

are performed on a subset or a combination of the total number of states N in the model. This results in a mapping from an internal state to an output. Additionally, these measurements are hampered by noise  . Moreover, many techniques used in biology (e.g. western blotting) necessitate the use of scaling and offset parameters

. Moreover, many techniques used in biology (e.g. western blotting) necessitate the use of scaling and offset parameters  (Kreutz et al., 2007). For ease of notation, we define

(Kreutz et al., 2007). For ease of notation, we define  as

as  , which lists all the parameters that should be defined in order to simulate the model.

, which lists all the parameters that should be defined in order to simulate the model.

|

(1) |

Considering M time series of length Ni with additive independent Gaussian noise, we can obtain (2) for the probability density function of the output data.

|

(2) |

| (3) |

In this equation yt represents the true system with true parameters  , whereas σi,j indicates the SD of a specific datapoint and K serves as a normalization constant. In maximum likelihood estimation (MLE), the goal is to find model parameters for which the probability density function most likely produced the data. In MLE one attempts to maximize the likelihood function

, whereas σi,j indicates the SD of a specific datapoint and K serves as a normalization constant. In maximum likelihood estimation (MLE), the goal is to find model parameters for which the probability density function most likely produced the data. In MLE one attempts to maximize the likelihood function  whose formula is identical to (2).

whose formula is identical to (2).

A second formalism commonly applied to inferential problems is known as Bayesian inference. In contrast to MLE, Bayesian inference does attach a notion of probability to the parameter values. Applying Bayes' theorem to the parameter estimation problem, we obtain (4). Since the probability of the data does not depend on the parameters, it merely acts as a normalizing constant. The posterior probability distribution is given by normalizing the likelihood multiplied with the prior to a unit area.

|

(4) |

Whereas MLE tends to focus on estimating best fit parameters, the Bayesian methodology attempts to elucidate posterior parameter probability distributions. In this article, we provide a strategy for uncertainty analysis consisting of multiple steps. By performing these steps sequentially we show how to avoid problems associated with the different techniques.

2 METHODS

We propose a strategy for performing prediction uncertainty analysis of biochemical networks. The four steps are discussed succinctly below. For further information, the reader is referred to the Supplementary Materials.

Step 1. Obtaining parameters (MLE and MAP):

MLE corresponds to finding the maximum of L. The quantity to be minimized becomes:

| (5) |

This can be recognized as a weighted sum of squared differences between model and data. Its Bayesian counterpart is the maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimator, which minimizes the log of the likelihood multiplied by the prior. Finding the optimum can be challenging due to the existence of multiple locally optimal solutions. Our approach begins by using a Monte Carlo multiple minimization (MCMM) approach, which basically entails performing the minimization for a large number of widely dispersed initial values. Such an initial run enables the modeller to probe the solution space for the existence of multiple minima at low computational cost.

Step 2. Parameter bounds and identifiability:

When model predictions sufficiently describe the experimental data, confidence intervals (CIs) are obtained using the profile likelihood (PL) method (Raue et al., 2009). Given that two models [ and

and  ] are nested (which means that one model can be transformed in the other by imposing linear constraints on the parameters), their likelihood ratio (LR) is approximately distributed according to a χ2p distribution. This distribution has p degrees of freedom, which are defined as the difference in the number of parameters. Intervals are computed for each parameter by forcing one parameter to change, while finding the region for which

] are nested (which means that one model can be transformed in the other by imposing linear constraints on the parameters), their likelihood ratio (LR) is approximately distributed according to a χ2p distribution. This distribution has p degrees of freedom, which are defined as the difference in the number of parameters. Intervals are computed for each parameter by forcing one parameter to change, while finding the region for which

| (6) |

continues to hold. While performing this traversal, the other parameters are continually re-optimized, hereby tracing a path through parameter space. In this equation α denotes a desired significance level. One starts with the best fit parameters and then changes one parameter (denoted with i) incrementally while optimizing for all the others. The weighted residual sum of squares (WRSSs) along the path can be written as:

| (7) |

Confidence bounds for each parameter are then obtained as the parameter values where (6) becomes an equality for the first time. Since one parameter is fixed at a new value, this χ2 distribution has one degree of freedom. The fact that each parameter is treated independently (performing only a 1D traversal for each parameter) makes this method efficient to compute.

In some cases, model parameters can be functionally related. These relations are referred to as structural non-identifiabilities and manifest themselves through a constant χ2PL,i for the involved parameters. Consequently no parameter confidence bound can be computed for such a parameter since a perturbation of one parameter can be negated by varying another. In other cases parameter bounds cannot be reliably inferred due to the measurement noise or a limited amount of information in the data. These parameters shall be referred to as practically non-identifiable. After performing the analysis, it is important to verify that the CI covers all the acceptable solutions obtained from the MCMM from Step 1. If this is not the case then this means that another local optimum apparently exists and the analysis should be repeated starting from this optimum. The profiles can then be merged afterwards.

Step 3. Assessing prediction uncertainty:

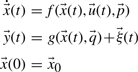

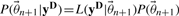

The Bayesian approach is somewhat different in the sense that the aim is to use the measurement data to infer a posterior distribution (8) rather than a single parameter set with CIs.

| (8) |

represents the conditional probability of the data given a parameter set. In our case, this is replaced by the likelihood function (which is proportional to this probability).

represents the conditional probability of the data given a parameter set. In our case, this is replaced by the likelihood function (which is proportional to this probability).  refers to the prior distribution of the parameters. Such a prior usually represents either the current state of knowledge or attempts to be non-informative or ‘objective’. Note that most priors are not re-parameterization invariant which demonstrates that uniform priors do not reflect complete objectivity (Jeffreys, 1946; Zwickl and Holder, 2004) in the Bayesian setting.

refers to the prior distribution of the parameters. Such a prior usually represents either the current state of knowledge or attempts to be non-informative or ‘objective’. Note that most priors are not re-parameterization invariant which demonstrates that uniform priors do not reflect complete objectivity (Jeffreys, 1946; Zwickl and Holder, 2004) in the Bayesian setting.

The next issue to address is how to actually sample from this posterior distribution. One class of methods that is often applied are Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) samplers. MCMC can generate samples from probability distributions whose probability densities are known up to a normalizing factor (Geyer, 1992). The Metropolis-Hastings algorithm is generally considered as the workhorse of MCMC methods. This algorithm performs a random walk through parameter space, where each step is based on a proposal distribution and an acceptance criterion based on the proposal and probability densities at the sampled points. Rather than sampling purely at random (where most of the samples would be from regions of low likelihood), such a chain samples proportionally to the likelihood multiplied by a prior. The histogram of such a parameter walk with respect to a specific parameter corresponds to the marginalized (integrated over all other variables) posterior parameter distribution for that specific parameter. The algorithm proceeds by iteratively performing a number of steps:

Generate a sample

by sampling from a proposal distribution based on the current state

by sampling from a proposal distribution based on the current state

Compute the likelihood of the data

and calculate

and calculate  , where

, where  refers to the prior density function.

refers to the prior density function.Draw a random number γ from a uniform distribution between 0 and 1 and accept the new step if

.

.

The ratio of Q is known as the Hastings correction which ensures detailed balance, a sufficient condition for the Markov Chain to converge to the equilibrium distribution. It corrects for the fact that the proposal density going from parameter set  to

to  and

and  to

to  is unequal when the proposal distribution depends on the current parameter set and is given by the inverse of this ratio.

is unequal when the proposal distribution depends on the current parameter set and is given by the inverse of this ratio.

The apparent simplicity of the algorithm makes it conceptually attractive. Note, however, that naive approaches can lead to MCMC samplers that converge slowly and/or stay in the local neighbourhood of a local mode (Calderhead and Girolami, 2009).

Proposals:

Each iteration requires a new proposal, which is taken from a proposal distribution. In order to effectively generate samples the proposal distribution adapts to the local geometry of the cost function. This becomes particularly important in the non-identifiable case as the parameters will be strongly correlated (Rannala, 2002). In such cases, large steps along the parameter correlations help accelerate convergence. To this end, we employ an adaptive Gaussian proposal distribution whose covariance matrix is based on a quadratic approximation to the cost function at the current parameter set (Gutenkunst et al., 2007). This matrix is computed by taking the inverse of an approximation to the Hessian matrix of the model under consideration. This proposal distribution is subsequently scaled by a problem specific proposal scaling factor that is tuned using short exploratory runs of the sampler.

In practical cases, some directions in parameter space can be so poorly constrained that this leads to a (near) singular Hessian. As a result, the proposal distribution will become extremely elongated in these directions, leading to propositions with extremely large or small parameter values and acceptance ratios decline. One approach to avoid such numerical difficulties is to set singular values below a certain threshold to a specific minimal threshold (prior to inversion) or to make use of a trust region approach. Additionally, we include second derivatives of the non-uniform priors (when available) in the Hessian approximation. For implementational details, the reader is referred to the supplement.

Parameter representation and non-identifiability:

The posterior distribution is required to be ‘proper’ (finitely integrable) otherwise the sampler will not converge and inference is not possible (Gelfand and Sahu, 1999). Without a proper prior that is finitely integrable to constrain the posterior distribution, improper likelihoods can lead to improper posteriors. It is clear that this becomes an issue when it comes to parameter non-identifiability where the data contains insufficient information about a specific parameter in order to result in a proper likelihood for that parameter. In such a case, empirical priors can ensure that parameters which are non-identifiable from the data do not drift off to extreme values (Gelfand and Sahu, 1999) hampering ODE integration and resulting in numerical instabilities. Note, however, that although such a prior makes the following analysis feasible, it artificially reduces the parameter uncertainty.

In order to deal with the large difference in scales, parameters can be considered in log-space. Note, however, that most prior distributions are not invariant to re-parameterization. The transformation between parameters can be described by the matrix of partial derivatives with respect to the equations which transform the parameters from one parameterization to another (the Jacobian of the transformation). In order to calculate the prior density that is equivalent under a different parameterization, one needs to multiply the prior probability density by the absolute value of the determinant of the Jacobian of the transformation. For further information see the Supplementary Material.

Convergence:

Burn in refers to the time it takes the chain to get to a region of high probability and samples taken during this period are generally discarded in order to avoid assigning too much weight to highly improbable samples. One approach to avoid a long burn-in period is by using a deterministic minimizer to obtain a best fit parameter set (Gutenkunst et al., 2007) which is likely to be a reasonable sample within the posterior probability distribution. Determining whether a sufficient number of samples has been acquired is hard to assess, and in practical situations only non-convergence can be diagnosed (Cowles and Carlin, 1996). In order to try and detect possible non-convergence, we divided one long chain into several batches and looked for systematic differences.

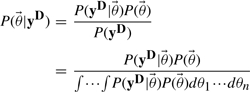

Step 4. Analysis of the posterior parameter and predictive distribution:

Having determined the posterior distribution of model predictions, there is now a direct link between different predictions and parameters, which can be exploited by determining how predictions relate to each other and to the model parameters. The uncertainty in the predictions y can be obtained by integrating the output over the posterior distribution of parameter values. Note that y can be any prediction obtained using the model. In other words, marginalizing the predictions over the converged MCMC chain provides us the prediction uncertainty as shown in Equation (9). Note that y can be any prediction that can be made with the model.

| (9) |

The posterior predictive distribution of simulations can be visualized by discretizing the state space and computing histograms per time point. Alternatively, we can compute credible intervals by selecting a desired probability and determining bounds that enclose this fraction of the posterior area. These bounds are chosen in such a way that the posterior density between the bounds is maximal. The posterior predictive distribution forms a link between the various predictions of interest, while being constrained by the available data and prior knowledge. By examining correlations between different states of interest it is possible to determine which states would be interesting to measure considering interest in a specific unmeasurable prediction. Similarly, such correlations can be explored between states and parameters, in order to determine which measurement could be used to avoid the necessity of having to use a prior.

In summary, the entire strategy consists of the following steps:

Detection of (multiple) acceptable parameter modes using an exploratory large scale search.

Detection of structural and practical non-identifiabilities using the PL.

Perform a Bayesian analysis considering detected non-identifiabilities from the PL method.

Perform an analysis of the posterior parameter and prediction space.

3 IMPLEMENTATION

All algorithms were implemented in Matlab (Natrick, MA). Numerical integration was performed using compiled MEX files using numerical integrators from the SUNDIALS CVode package (Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Livermore, CA).

To perform the initial large scale search, we performed random sampling using a uniform hypercube to obtain initial parameter values. These were subsequently optimized using the Levenberg–Marquardt minimizer from the MATLAB optimization toolbox. The best fit was subsequently selected and used for determining the PL. In order to attain an adequate acceptance rate and good mixing, the proposal scaling for the MCMC was determined during an initial tuning stage. This tuning was performed by running many short chains (100 iterations each), targeting an acceptance rate between 0.2 and 0.4 (Gilks et al., 1996). Furthermore, the MCMC was performed in log-space.

4 RESULTS

We illustrate our approach using a model of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway (Raue et al., 2009; Toni et al., 2009). The model is based on a number of hypothesized steps (see the Supplementary Material for model equations). First erythropoietin (EpoR) activates the EpoR receptor which phosphorylates cytoplasmic STAT (x1). This phosphorylated STAT (x2) dimerizes (x3) and is subsequently imported into the nucleus (x4). Here dissociation and dephosphorylation occurs, which is associated with a delay. Similar to the implementation given in the original article, the driving input function was approximated by a spline interpolant, while the delay was approximated using a linear chain approximation.

We used data from the article by Swameye et al. (dataset 1) for parameterization and inference (Swameye et al., 2003). Observables were the total concentration of STAT and the total concentration of phosphorylated STAT in the cytoplasm, both reported in arbitrary units thereby requiring two additional scaling parameters s1 and s2. The initial cytoplasmic concentration of STAT is unknown while all other forms of STAT are assumed zero at the start of the simulation. The vector of unknown parameter values consists of the elements  .

.

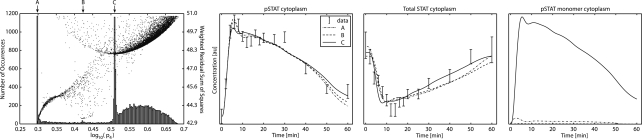

In order to investigate the existence of multiple modes, we first performed a large scale search using MCMM with initial parameters based on a log uniform random sampling between the ranges 10−3 and 102 (N=10 000). After optimization, samples are either accepted or rejected based on the LR bound based on the best fit value. The resulting distribution and associated WRSS are shown in Figure 1. It is clear that there are at least three local minima in the likelihood. Although all three modes describe the data adequately, they show different prediction results for the unobserved internal states of the model.

Fig. 1.

Left: histogram of final parameter values for parameter p4 post optimization (bars), and their associated WRSSs (dots). Note that all of the optimized parameter sets shown are acceptable with respect to the LR ratio. Right: model predictions from parameter sets taken from location A, B and C for two measured outputs as well as one unmeasured internal state.

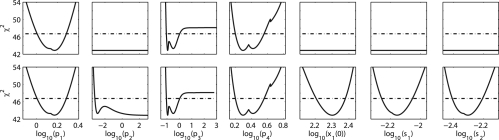

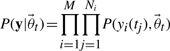

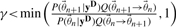

Subsequently, a PL analysis was performed. In order to increase confidence that no acceptable regions of parameter space were missed, we started PLs from each mode detected using the MCMM method (Step 1). Subsequently we merged these profiles and verified whether they covered the full span of acceptable parameter sets obtained in Step 1. Based on the PL, shown in the top panel of Figure 2, it can be concluded that the model based on first principles is structurally non-identifiable (Raue et al., 2009). From scatter plots of the PLs (shown in the supplement), it was determined that the parameters x10, s1 and s2 were structurally related and therefore unidentifiable. Analogously to (Raue et al., 2009) we specify a Gaussian prior (μ=200 nM, σ=20 nM) for the initial condition (which is comparable to assuming that the initial concentration was measured with this accuracy). In order to check whether the prior affects the profiles in the desired manner one can compute new profiles using MAP estimation (by incorporating the prior in the procedure). In our case, the Gaussian prior constrains both the initial condition as well as both scaling factors (see Fig. 2). We can also observe that parameter p2 is practically non-identifiable at α=0.05.

Fig. 2.

PLs of the JAK-STAT model. Top: without prior on the initial condition, Bottom: with prior on the initial condition.

In the case of JAK-STAT, at least three priors are required to render the model ‘identifiable’ for all levels of significance. As the name suggests, priors based on prior belief are preferred. However, in many cases, little is known beforehand regarding the parameters of a system. For the initial condition we specify a Gaussian prior (μ=200 nM, σ=20 nM), while we apply a log uniform prior with support from 10−8 to 102 and 10−8 to 101.5 for parameters p2 and p3. The other parameters are given unbounded log uniform prior distributions.

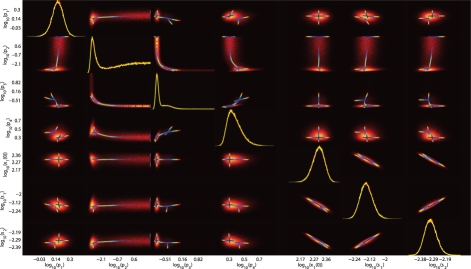

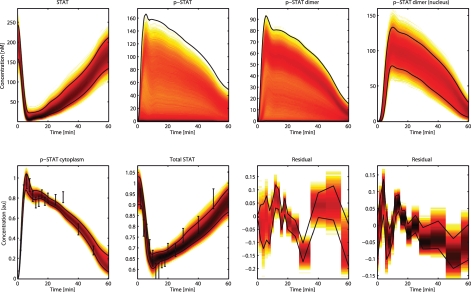

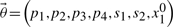

As shown in Figure 3, the parameter bounds based on PL agree well with those based on the MCMC sampling for the identifiable parameters. What can also be observed, however, is that parameter sets that would be considered likely based only on data can still be improbable when the prior probabilities are also taken into account. This can be observed for parameter p3 where the PL path reveals two modes that are almost equally likely, yet show large difference in terms of probability density. The posterior parameter distribution does contain a few samples in this region, but relatively little mass. It is an example of the difference between integration and maximization and indicates that this region corresponds to a sharp ridge in the likelihood. This observation was verified using a second MCMC method (Girolami and Calderhead, 2011) (see Supplementary Material). As shown in Figure 4, the current approach makes it possible to infer a posterior predictive distribution. Regarding the MCMC results, the assumed prior distributions could be a point of debate. Correlation analysis on the predictions revealed that state two had a strong dependence on the prior distribution of parameter p2. This indicates that predictions regarding state two should be made with care.

Fig. 3.

Histograms of the posterior distribution. Shown on the diagonal are the marginal (integrated) distributions of the parameters, where different colours indicate different batches of samples. Off the diagonal are the joint probability distributions between two parameters. The correlated nature of several parameters can clearly be observed. Lines indicate PL trajectories where blue and red corresponds to a good and bad fit, respectively. Note that the PL includes the prior on the scaling.

Fig. 4.

Posterior predictive distribution of model predictions (colours) with 95% credible intervals (black lines). Top: unmeasured internal model predictions. Bottom: measured model output, data ±SD and residual distributions.

Once a sample from the posterior distribution is obtained, the results can be used for a wide array of model analysis techniques. Using a sample of parameter sets that reflects the uncertainty in the parameter estimates avoids conclusions that are not supported by the given data and prior knowledge. Relations within the posterior distribution and also its relation to the posterior predictive distribution can be probed in order to determine how different predictions in the model relate to each other. One example for this specific case is shown in the Supplementary Materials, where we can observe a transient correlation between states 3 and 4.

5 DISCUSSION

In this article, we proposed a new strategy for prediction uncertainty analysis. By performing PL analysis, we were able to specify sufficient priors to ensure that the posterior distribution was proper and could be sampled from. Using MCMC a sample of parameter sets proportional to the probability density of that parameter set was obtained. The strategy enables a comprehensive analysis on the effect of parameter uncertainty on model predictions and enables the modeller to relate these effects to the model parameters.

Given a sufficient amount of data, such an analysis should be relatively insensitive to the assumed priors. As observed in the case of JAK-STAT, however, it can be seen that even for a small model, identifiability can be problematic. It is important to realize that in such cases the choice of priors will affect the outcome of the analysis. Furthermore, most priors are not re-parameterization invariant and therefore uniform priors do not reflect complete ignorance. Although seemingly uninformative, a uniform prior in untransformed parameter space implies that extremely large rates have an equal a-priori probability of occurring than slow rates. In our case, for the completely unknown kinetic parameters we assumed a uniform prior in logarithmic space. For positively defined parameters, a uniform distribution in logarithmic space corresponds to an uninformative prior (Box and Tiao, 1973). Such a prior gives equal probability to different orders of magnitude (scales). An approximate scale invariance of kinetic parameters has indeed been observed in biological models (Grandison and Morris, 2008). Note that in a Bayesian analysis there is no such thing as not specifying a prior.

Our strategy can be used to gain insight into prediction uncertainty. Note, however, that aside from the computational model and the prior distributions, the noise model also affects the resulting posterior distribution. It should be stressed that investigating what kind of noise model to use when (and subsequently determining the appropriate likelihood function for this noise model) is important. Practical soluti ons to non-additive noise can usually be found. One example would be a multiplicative noise model (which is often associated with non-negative data), where data preprocessing such as taking the logarithm of both the model and data can help alleviate problems (Kreutz et al., 2007). If the likelihood function truly becomes intractable, then one can resort to approximate Bayesian methods, where rather than computing the likelihood function, one computes a distance metric between simulations (with simulated noise) and data (Toni et al., 2009).

When the goal of prediction uncertainty analysis is model falsification then one could opt for an approach based on interval analysis (Hasenauer et al., 2010a, b). In these works, uncertainty analysis is reformulated into a feasibility problem. Using this approach, regions of parameter space that cannot describe the data can systematically be determined. An attractive aspect of these methods is that these methods provide guarantees on finite parameter searches, but have up to this point only been performed on small scale models.

Different approaches for prediction uncertainty analysis based on optimization are proposed in (Brännmark et al., 2010; Cedersund and Roll, 2009; Nyman et al., 2011). Such methods are useful for probing consistent behaviour (termed core predictions) among multiple parameter sets, even in the non-identifiable case. However, they do not result in a probabilistic assessment of the prediction uncertainty. Probing consistent behaviour is also the main focus of a workflow proposed by (Gomez-Cabrero et al., 2011) for classifying consistent model behaviours and hypotheses.

Several steps in the proposed approach are computationally challenging and require many model evaluations. Because of this, model simulation time is a primary concern. Many packages (including ours) have been able to attain significant simulation speed-ups by compiling simulation code, reducing model evaluation time by up to two orders of magnitude [Potters Wheel (Maiwald and Timmer, 2008); COPASI (Hoops et al., 2006); Sloppy Cell (Brown and Sethna, 2003)]. Additionally, new computational platforms such as general purpose programming on the graphical processing unit are being explored (Liepe et al., 2010).

In conclusion, our strategy enables the modeller to account for parameter uncertainty when making model predictions. In the case of a fully identifiable model, we can work with uninformative priors and overconfident conclusions that could result from a model described by a single parameter set can be avoided. Regarding non-identifiable models, a practical approach can be adopted where the dependence with respect to the assumed prior distributions can be determined a posteriori. Note that though this makes computing the posterior distribution feasible, such an approach underestimates the parameter uncertainty. Performing the analysis and obtaining a sample from the posterior takes considerably more computational effort than determining a single parameter set. However, once such a sample is obtained, the results can be used for a wide array of model analysis techniques which more than warrants the additional computational time invested. Relations within this posterior distribution and also its relation to the posterior predictive distribution can be extracted. This helps uncovering how different predictions in the model relate to each other and therefore how the system behaves.

Funding: This work was funded by the Netherlands Consortium for Systems Biology (NCSB).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- Box G., Tiao G. Bayesian Inference in Statistical Analysis. Reading, MA: Wiley Online Library. Addison Wesley; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Brännmark C., et al. Mass and information feedbacks through receptor endocytosis govern insulin signaling as revealed using a parameter-free modeling framework. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:20171–20179. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.106849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown K.S., Sethna J.P. Statistical mechanical approaches to models with many poorly known parameters. Phys. Rev. E. 2003;68:021904. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.68.021904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderhead B., Girolami M. Estimating Bayes factors via thermodynamic integration and population MCMC. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2009;53:4028–4045. [Google Scholar]

- Cedersund G., Roll J. Systems biology: model based evaluation and comparison of potential explanations for given biological data. FEBS J. 2009;276:903–922. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowles M., Carlin B. Markov chain Monte Carlo convergence diagnostics: a comparative review. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1996;91:883–904. [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand A., Sahu S. Identifiability, improper priors, and gibbs sampling for generalized linear models. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1999;94:247–253. [Google Scholar]

- Geyer C. Practical Markov chain Monte Carlo. Stat. Sci. 1992;7:473–483. [Google Scholar]

- Gilks W., et al. Interdisciplinary Statistics. Chapman & Hall; 1996. Markov Chain Monte Carlo in Practice. [Google Scholar]

- Girolami M., Calderhead B. Riemann manifold langevin and hamiltonian monte carlo methods. J. Roy. Stat. Soc. B Stat. Meth. 2011;73:123–214. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Cabrero D., et al. Workflow for generating competing hypothesis from models with parameter uncertainty. Interf. Focus. 2011;1:438–449. doi: 10.1098/rsfs.2011.0015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandison S., Morris R. Biological pathway kinetic rate constants are scale-invariant. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:741–743. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutenkunst R.N., et al. Universally sloppy parameter sensitivities in systems biology models. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2007;3:e189. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasenauer J., et al. Guaranteed steady state bounds for uncertain (bio-) chemical processes using infeasibility certificates. J. Process Contr. 2010a;20:1076–1083. [Google Scholar]

- Hasenauer J., et al. Parameter identification, experimental design and model falsification for biological network models using semidefinite programming. IET Syst. Biol. 2010b;4:119–130. doi: 10.1049/iet-syb.2009.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoops S., et al. Copasia complex pathway simulator. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:3067–3074. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffreys H. An invariant form for the prior probability in estimation problems. Proc. Roy. Soc. Lond. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1946;186:453–461. doi: 10.1098/rspa.1946.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreutz C., et al. An error model for protein quantification. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2747–2753. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liepe J., et al. ABC-SysBio—approximate Bayesian computation in Python with GPU support. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:1797–1799. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiwald T., Timmer J. Dynamical modeling and multi-experiment fitting with potterswheel. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2037–2043. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyman E., et al. A hierarchical whole-body modeling approach elucidates the link between in vitro insulin signaling and in vivo glucose homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:26028–26041. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.188987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rannala B. Identifiability of parameters in MCMC Bayesian inference of phylogeny. Syst. Biol. 2002;51:754–760. doi: 10.1080/10635150290102429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raue A., et al. Structural and practical identifiability analysis of partially observed dynamical models by exploiting the PL. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1923–1929. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swameye I., et al. Identification of nucleocytoplasmic cycling as a remote sensor in cellular signaling by databased modeling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:1028–1033. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0237333100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toni T., et al. Approximate Bayesian computation scheme for parameter inference and model selection in dynamical systems. J. Roy. Soc. Interf. 2009;6:187–202. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2008.0172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwickl D., Holder M. Model parameterization, prior distributions, and the general time-reversible model in Bayesian phylogenetics. Syst. Biol. 2004;53:877–888. doi: 10.1080/10635150490522584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.