Abstract

Motivation: High-throughput sequencing has made the analysis of new model organisms more affordable. Although assembling a new genome can still be costly and difficult, it is possible to use RNA-seq to sequence mRNA. In the absence of a known genome, it is necessary to assemble these sequences de novo, taking into account possible alternative isoforms and the dynamic range of expression values.

Results: We present a software package named Oases designed to heuristically assemble RNA-seq reads in the absence of a reference genome, across a broad spectrum of expression values and in presence of alternative isoforms. It achieves this by using an array of hash lengths, a dynamic filtering of noise, a robust resolution of alternative splicing events and the efficient merging of multiple assemblies. It was tested on human and mouse RNA-seq data and is shown to improve significantly on the transABySS and Trinity de novo transcriptome assemblers.

Availability and implementation: Oases is freely available under the GPL license at www.ebi.ac.uk/~zerbino/oases/

Contact: dzerbino@ucsc.edu

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Next-generation sequencing of expressed mRNAs (RNA-seq) is gradually transforming the field of transcriptomics (Blencowe et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2009). The first attempts to discover expressed gene isoforms relied on mapping the RNA-seq reads onto the exons and exon–exon junctions of a known annotation (Jiang and Wong 2009; Mortazavi et al., 2008; Richard et al., 2010; Sultan et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2008). Consequently, reference-based ab initio methods have been developed to assemble a transcriptome from RNA-seq data using read alignments alone, inferring the underlying annotation (Denoeud et al., 2008; Guttman et al., 2010; Trapnell et al., 2010; Yassour et al., 2009).

Unfortunately, the use of a reference genome is not always possible. Despite the drop in the cost of sequencing reagents, the complete study of a genome, from sampling to finishing the assembly is still costly and difficult. Sometimes, the model being studied is sufficiently different from the reference because it comes from a different strain or line such that the mappings are not altogether reliable. For these cases, de novo genome assemblers have been employed to create transcript assemblies, or transfrags, from the RNA-seq reads in the absence of a reference genome (Birol et al., 2009; Collins et al., 2008; Jackson et al., 2009; Wakaguri et al, 2009).

However, these short read genomic assemblers, based mainly on de Bruijn graph genomic assemblers (Zerbino and Birney, 2008; Simpson et al., 2009), make implicit assumptions regarding the evenness of the coverage and the colinearity of the sequence. Indeed, the coverage depth fluctuates significantly between transcripts, isoforms and regions of the transcript, therefore it cannot be used to determine the uniqueness of regions or to isolate erroneous sequence. In addition, these tools are geared to produce long linear contigs from the given sequence, not to detect the overlapping sequences presented by isoforms of a single gene. This affects a number of steps, including error correction, repeat detection and read pair usage. These methods are therefore not necessarily suited to process transcriptome data which does not conform to either of these assumptions.

More recently, transcriptome assembly pipelines were developed to post-process the output of de novo genome assemblers: Velvet and ABySS (Martin et al., 2010; Robertson et al., 2010; Surget-Groba and Montoya-Burgos, 2010). The common idea shared by these pipelines is to run an assembler at different k-mer lengths and to merge these assemblies into one. The rationale behind this approach is to merge more sensitive (lower values of k) and more specific assemblies (higher values of k).

The pipeline presented by Robertson et al. (2010), transABySS, also handles alternative splicing variants. It detects them by searching for connected groups of contigs such that they are connected in a characteristic bubble and one of the contigs has a length of exactly (2k−2). These bubbles are first removed, then added to the final assemblies, to reconstruct alternate variants.

A variety of algorithmic researchers have used splicing graphs to represent alternative splicing which have a direct relationship to de Bruijn graphs, as pointed out by Heber et al. (2002). This homology between data structures opens the possibility of a de novo short read transcriptome assembler, as illustrated by the Trinity algorithm (Yassour et al., 2011). Trinity starts by extending contigs greedily, connecting them into a de Bruijn graph, then extracting sufficiently covered paths through this graph. Trinity is designed to reconstruct highly expressed transcripts to full length using only one k-mer length.

We present Oases, a de novo transcriptome assembler that combines these advances. Oases merges the use of multiple k-mers presented in (Robertson et al., 2010; Surget-Groba and Montoya-Burgos, 2010) with a topological analysis similar to that presented by Yassour et al. (2011). It uses dynamic error removal adapted to RNA-seq data and implements a robust method to predict full length transfrags, even in cases where noise perturbs the topology of the graph. Single k assemblies are merged to cover genes at different expression levels without redundancy.

We tested the latest version of Oases (0.2.01) on experimental datasets and found that Oases produces longer assemblies than previous de novo RNA-seq assemblers. Oases was compared with a reference-based ab initio algorithm, Cufflinks (Trapnell et al., 2010). The latter approach has a considerable advantage in low expression genes, as it can join otherwise disjoint reads by virtue of their genomic positions, but at high read coverage, Oases' sensitivity approaches that of reference-based ab initio algorithms. We also examined the effect of coverage depth, hash length, alternative splicing and assembly merging on the quality of assemblies.

2 METHODS

2.1 Overview

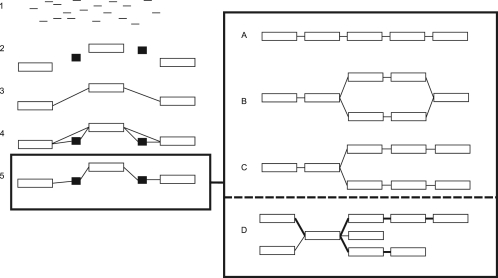

The Oases assembly process, explained in detail below and illustrated in Figure 1, consists of independent assemblies, which vary by one important parameter, the hash (or k-mer) length. In each of the assemblies, the reads are used to build a de Bruijn graph, which is then simplified for errors, organized into a scaffold, divided into loci and finally analyzed to extract transcript assemblies or transfrags. Once all of the individual k-mer assemblies are finished, they are merged into a final assembly.

Fig. 1.

Schematic overview of the Oases pipeline: (1) Individual reads are sequenced from an RNA sample; (2) Contigs are built from those reads, some of them are labeled as long (clear), others short (dark); (3) Long contigs, connected by single reads or read-pairs are grouped into connected components called loci; (4) Short contigs are attached to the loci; and (5) The loci are transitively reduced. Tranfrags are then extracted from the loci. The loci are divided into four categories: (A) chains, (B) bubbles, (C) forks and (D) complex (i.e. all the loci which did not fit into the previous categories).

2.2 Contig assembly

The Oases pipeline receives as input a preliminary assembly produced by the Velvet assembler (Zerbino and Birney, 2008) which was designed to produce scaffolds from genomic readsets. Its initial stages, namely hashing and graph construction can be used indifferently on transcriptome data. We only run these stages of Velvet to produce a preliminary fragmented assembly, containing the mapping of the reads onto a set of contigs.

However, the later stage algorithms, Pebble and Rock Band, which resolve repeats in Velvet, are not used because they rely on assumptions related to genomic sequencing (Zerbino et al., 2009). Namely, the coverage distribution should be roughly uniform across the genome and the genome should not contain any branching point. These conditions prevent those algorithms from being reliable and efficient on RNA-seq data.

2.3 Contig correction

After reading the contigs produced by Velvet, Oases proceeds to correct them again with a set of dynamic and static filters.

The first dynamic correction is a slightly modified version of Velvet's error correction algorithm, TourBus. TourBus searches through the graph for parallel paths that have the same starting and end node. If their sequences are similar enough, the path with lower coverage is merged into the path with higher coverage, irrespective of their absolute coverage. In this sense, the TourBus algorithm is adapted to RNA-seq data and fluctuating coverage depths. However, for performance issues, the Velvet version of TourBus only visits each node once, meaning that it does not exhaustively compare all possible pairs of paths. Given the high coverage of certain genes, and the complexity of the corresponding graphs, with numerous false positive paths, it is necessary for Oases to exhaustively examine the graph, visiting nodes several times if necessary.

In addition to this correction, Oases includes a local edge removal. For each node, an outgoing edge is removed if its coverage represents <10% of the sum of coverages of outgoing edges from that same node. This approach, similar to the one presented by Yassour et al. (2011), is based on the assumption that on high coverage regions, spurious errors are likely to reoccur more often.

Finally, all contigs with less than a static coverage cutoff (by default 3×) are removed from the assembly. The rationale for this filter is that any transcript with such a low coverage cannot be properly assembled in the first place, so it is expedient to remove them from the assembly, along with many low coverage contigs created by spurious errors.

2.4 Scaffold construction

The distance information between the contigs is then summarized into a set of distance estimates called a scaffold, as described in (Zerbino et al., 2009). Because a read in a de Bruijn graph can be split between several contigs, the distance estimate for a connection between two contigs can be supported by both spanning single reads or paired-end reads.

The total number of spanning reads and pair-end reads confirming a connection is called its support. A connection which is supported by at least one spanning read is called direct, otherwise, it is indirect.

Connections are assigned a total weight. It is calculated by adding 1 for each supporting spanning read and a probabilistic weight for each spanning pair, proportional to the likelihood of observing the paired reads at their observed positions on the contigs given the estimated distance between the contigs and assuming a normal insert length distribution model.

2.5 Scaffold filtering

Much like the contig correction phase, several filters are applied to the scaffold: static coverage thresholds for the very low coverage sequences and a dynamic coverage threshold that adapts to the local coverage depth.

Because coverage is no longer indicative of the uniqueness of a sequence, contig length is used as an indicator. Based on the decreasing likelihood of high identity conservation as a function of sequence length (Whiteford et al., 2005), contigs longer than a given threshold [by default (50+k−1) bp] are labeled as long and treated as if unique and the other nodes are labeled as short.

Connections with a low support (by default 3× or lower) or with a weight <0.1 are first removed. Two short contigs can only be joined by a direct connection with no intermediate gap. A short and a long contig can only be connected by a direct connection.

Finally, connections between long contigs are tested against a modified version of the statistic presented in (Zerbino et al., 2009), which estimates how many read pairs should connect two contigs given their respective coverages and the estimated distance separating them (see Supplementary Material). Indirect connections with a support lower than a given threshold (by default 10% of this expected count) are thus eliminated.

2.6 Locus construction

Oases then organizes the contigs into clusters called loci, as illustrated in Figure 1. This terminology stems from the fact that in the ideal case, where no gap in coverage or overlap with exterior sequences complicate matters, all the transcripts from one gene should be assembled into a connected component of contigs. Unfortunately, in experimental conditions, this equivalence between components and genes cannot be guaranteed. It is to be expected that loci sometimes represent fragments of genes or clusters of homologous sequences.

Scaffold construction takes place in two stages similarly to the approach described by Butler et al. (2008). Long contigs are first clustered into connected components. These long nodes have a higher likelihood of being unique, therefore it is assumed that two contigs which belong to the same component also belong to the same gene. To each locus are added the short nodes which are connected to one of the long nodes in the cluster.

2.7 Transitive reduction of the loci

For the following analyses to function properly, it is necessary to remove redundant long distance connections, and retain only connections between immediate neighbors, as seen in Figure 1. For example, it is common that two contigs which are not consecutive in a locus are connected by a paired-end read.

A connection is considered redundant if it connects two nodes that are connected by a distinct path of connections such that the connection and the two paths have comparable lengths. The transitive reduction implemented in Oases is inspired from the one described in (Myers, 2005) but had to be adapted to the conditions of short read data. In particular, short contigs can be repeated or even inverted within a single transcript and form loops in the connection graph. Because of this, occasional situations arise where every connection coming out of a node can be transitively reduced by another one, thus removing all of them, and breaking the connectivity of the locus. To avoid this, a limit is imposed on the number of removed connections. If two connections have the capacity to reduce each other, the shortest one is preserved.

2.8 Extracting transcript assemblies

The sequence information of the transcripts is now contained in the loci. These loci can be fragmented because of alternative splicing events which cause the de Bruijn graph to have a branch. Oases, therefore, analyses the topology of the loci to extract full length isoform assemblies.

In many cases, the loci present a simple topology which can be trivially and uniquely decomposed as one or two transcripts. We define three categories of trivial locus topologies (Fig. 1): chains, forks and bubbles, which if isolated from any other branching point, are straightforward to resolve. These three topologies are easily identifiable using the degrees of the nodes. Oases, therefore, detects all the trivial loci and enumerates the possible transcripts for each of them.

Because the above exact method only applies to specific cases, an additional robust heuristic method is applied to the remaining loci, referred to as complex loci. Oases uses a reimplementation of the algorithm described in (Lee, 2003), which efficiently produces a parsimonious set of putative highly expressed transcripts, assuming independence of the alternative splicing events.

This extension of the algorithm is quite intuitive, since there is a direct analogy between the de Bruijn graph built from the transcripts of a gene and its splicing graph, as noted by Heber et al. (2002). Using dynamic programming, it enumerates heavily weighted paths through the locus graph in decreasing order of coverage, until either all the contigs of the locus are covered, or a specified number of transcripts is produced (by default 10).

As in the transitive reduction phase, this algorithm had to be slightly modified to allow for loops in the putative splicing graph of the locus. Loops are problematic because their presence can prevent the propagation of the dynamic programming algorithm to all the contigs of a locus. When a loop is detected, it is broken at a contig which connects the loop to the rest of the locus, so as to leave a minimum number of branch points, as described in the Supplementary Material.

2.9 Merging assemblies with Oases-M

De Bruijn graph assemblers are very sensitive to the setting of the hash length k. For transcriptome data, this optimization is more complex as transcript expression levels and coverage depths are distributed over a wide range. A way to avoid the dependence on the parameter k is to produce a merged transcriptome assembly of previously generated transfrags from Oases.

Oases is run for a set of [kMIN,…,kMAX] values and the output transfrags are stored. All predicted transfrags from runs in the interval are then fed into the second stage of the pipeline, Oases-M, with a user selected kMERGE. A de Bruijn graph for kMERGE is built from these transfrags. After removing small variants with the Tourbus algorithm, any transfrag in the graph that is identical or included in another transfrag is removed. The final assembly is constructed by following the remaining transfrags through the merged graph.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Datasets

Two datasets were retrieved from the Nucleotide Archive (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/). A human dataset was produced in a study by Heap et al. (2010), where poly(A)-selected RNAs from human primary CD4(+) T cells were sequenced. Paired-end reads of length 45 bp with an insert size of 200 bp from one human individual (studyID SRX011545) were downloaded.

A mouse dataset was taken from the study of Trapnell et al. (2010). In a timeseries experiment of C2C12 myoblast mouse cells, paired-end reads of length 75 bp with an insert size of 300 bp were sequenced. Read data from the 24 h timepoint (study id SRX017794) was used.

To reduce the amount of erroneous bases, both paired-end datasets were processed by (i) removing Ns from both ends, (ii) clipping bases with a Sanger quality ≤10 and (iii) removing reads with more than six bases with Sanger quality ≤10 after steps (i) and (ii), leading to a total of 30 940 088 and 64 441 708 reads for human and mouse, respectively.

3.2 Assemblies and alignments

All experiments were run with Oases version 0.2.01, and Velvet 1.1.06 and the coverage cutoff and the minimum support for connections were set to 3.

TransABySS 1.2.0 was run with ABySS 1.2.5 through the first two stages of transABySS (assembly and merging, before mapping to a reference genome is required). Instead of just running with the default parameters, we tested an array of parameters and chose the best for those datasets, namely n=10, c=3 and ABYSS with the options -E0 (Supplementary Material).

Trinity (ver. 2011-08-20) was run with the default parameters. In particular, the k-mer length of 25 could not be modified.

Potential poly-A tails after assembly were removed using the trimEST program from the EMBOSS package (Rice et al., 2000) before alignment. Subsequently, predicted transfrags of the methods were aligned against the genome using Blat (Kent, 2002).

The Cufflinks assemblies are those published by its authors.

Reads per kilobase of exon model per million mapped reads (RPKM), as defined by Mortazavi et al. (2008) expression values for annotated genes have been computed by aligning reads against annotated Ensembl 57 transcripts with RazerS (Weese et al., 2009), (see Supplementary Material).

3.3 Metrics

In all the following experiments, we focused on a simple set of metrics as used in (Robertson, 2010; Yassour, 2011): nucleotide sensitivity, nucleotide specificity, percentage of transcripts assembled to 100% of their length and percentage of transcripts assembled to 80% of their length. The Blat mappings of the assemblies were compared with the Ensembl annotations of the corresponding species.

3.4 Comparing Oases to Velvet

To evaluate the added value of the topology resolution within each loci, we compared the Oases contigs from the Velvet assemblies which they are built from. Table 1 shows how the Oases assemblies significantly improve on the Velvet assemblies. This confirms the intuition that in the presence of alternative splicing and dynamic expression levels, the assembly is broken by breaks in the graph, which can be resolved by topological analysis and adapted error correction as described in the Methods section.

Table 1.

Comparison of Velvet and Oases assemblies on the human RNA-seq dataset

| k-mer | Method | Tfrags > 100 bp | Sens. (%) | Spec. (%) | Full Lgth. | 80% lgth. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 | Velvet | 89 789 | 12.45 | 83.58 | 42 | 78 |

| Oases | 67 319 | 17.23 | 92.55 | 828 | 7437 | |

| 25 | Velvet | 88 042 | 16.13 | 89.62 | 92 | 516 |

| Oases | 53 504 | 14.97 | 93.0 | 754 | 6882 | |

| 31 | Velvet | 55 986 | 12.78 | 93.16 | 213 | 1986 |

| Oases | 47 878 | 10.55 | 94.63 | 429 | 3751 | |

| 35 | Velvet | 36 507 | 7.9 | 94.81 | 107 | 1660 |

| Oases | 34 012 | 6.67 | 95.99 | 196 | 1885 |

The total number of transfrags longer that 100 bp (Tfrags), nucleotide sensitivity and specificity, as well as the number of full length or 80% length reconstructed Ensembl transcripts are shown.

As an example, the percentage cutoff for local edge removal was modulated (see Supplementary Table S1). These results show how dynamic filters improve the quality of the assembly.

3.5 Impact of k-mer lengths

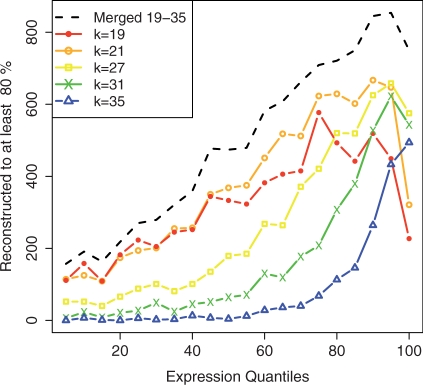

One of the major parameters in de Bruijn graph assemblers is the hash length, or k-mer length. Comparing single-k assemblies performed by Oases, it is possible to observe that this parameter is crucial in RNA-seq assembly. Figure 2 shows how the k-mer length is closely related to the expression level of the transcripts being assembled. As expected, the assemblies with longer k-values perform best on high expression genes, but poorly on low expression genes. However, short k-mer assemblies have the disadvantage of introducing misassemblies, as shown in Supplementary Table S7.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of single k-mer Oases assemblies and the merged assembly from kMIN=19 to kMAX=35 by Oases-M, on the human dataset. The total number of Ensembl transcripts assembled to 80 of their length is provided by RPKM gene expression quantiles of 1464 genes each.

3.6 Impact of merging assemblies

In addition, Figure 2 shows the same statistics for the merged assembly by Oases-M, which is significantly superior to each of the individual values. This result illustrates how the different assemblies do not completely overlap. Further, Supplementary Figure S2 shows how each single k-mer assembly resolved transcripts at different expression levels.

We compared merging different intervals of k-mers (see Supplementary Material). The wider the interval, the better the results. To determine bounds on this interval we arbitrarily bounded on the low values with 19, on the assumption that smaller k-mers are very likely to be unspecific for mammalian genomes (Whiteford et al., 2005). In theory, on the upper end, all the k-mer values (up to read length) could be used. To avoid wasting resources, we measured the added value of each new assembly (see Supplementary Material). As expected, marginal gains progressively diminish and this metric could be used to determine how large a spectrum of k-mers to use. We also investigated which kMERGE should be used and we found that kMERGE= 27 works well with little difference for higher values (see Supplementary Table S4) and is therefore used for all analyses in the article.

3.7 Comparing Oases to other RNA-seq de novo assemblers

Oases-M was compared with existing RNA-seq de novo assemblers, transABySS (Robertson et al., 2010) and Trinity (Yassour et al., 2011). The previous human dataset and a mouse dataset were used for the comparison. The datasets have different read lengths and sequencing depth, as detailed in Methods. Both transABySS and Oases were run for k-mer length 19–35 bp on the human dataset. Because the mouse reads are longer, these two assemblers were run for k-mers 21–35 on that dataset. The highest value of k was determined by an approach similar to that used on the human data (see Supplementary Material for data). Trinity is fixed by implementation at k=25 bp.

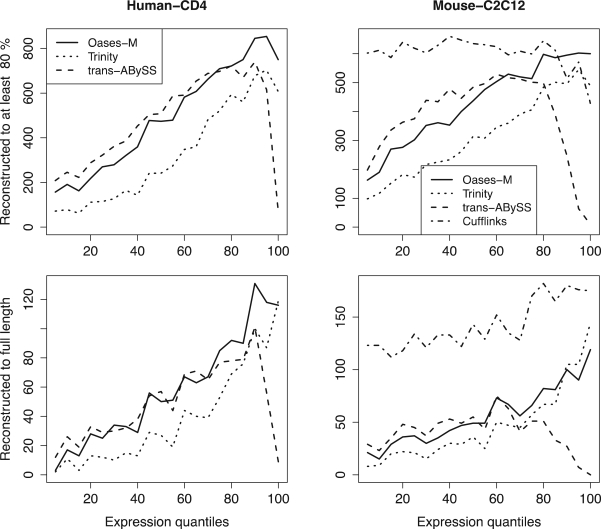

Figure 3 shows the number of reconstructed Ensembl transcripts for each assembler on both datasets separated by expression quantiles. The main observation is that all assemblers do not behave equally with respect to expression level. Trinity appears to perform best on high expression genes, whereas transABySS performs best on low expression genes. Oases performs comparatively well throughout the spectrum of expression levels, hence the greater overall success (Table 2).

Fig. 3.

Reconstruction efficiency of Ensembl transcripts for different RNA-seq de novo assembly methods (Oases-M, Trinity, and transABySS) on human and mouse datasets. Reference-based assembly results using Cufflinks are provided on the mouse dataset. All annotated genes have been grouped into quantiles by RPKM expression values of 1464 (resp. 1078) genes for the human data (resp. mouse).

Table 2.

Overall comparison of the different RNA-seq assembly methods on human and mouse datasets

| Data | Method | Tfrags > 100 bp | Sens. (%) | Spec. (%) | Full lgth | 80% lgth |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | Oases-M | 174 469 | 21.44 | 92.35 | 1463 | 11 169 |

| tABySS | 100 127 | 19.65 | 92.16 | 1358 | 10 992 | |

| Trinity | 76 232 | 19.99 | 88.63 | 953 | 7129 | |

| Mouse | Oases-M | 175 914 | 30.83 | 89.08 | 1324 | 9880 |

| tABySS | 174 744 | 30.66 | 92.79 | 1149 | 9376 | |

| Trinity | 92 810 | 31.57 | 87.14 | 1085 | 7028 | |

| Cufflinks | 63 207 | 48.13 | 75.29 | 4369 | 21 222 |

The number of transfrags longer than 100 bp produced (Tfrags) and nucleotide sensitivity and specificity, as well as the number of full length or 80% length reconstructed Ensembl transcripts are shown.

Regarding correctness, we computed the number of misassemblies and the qualities of the different assemblers are comparable (see Supplementary Material). Transfrags mapped with high confidence to the genome occasionally differ from the known annotation. For example, Oases produced 237 (resp. 390) transfrags longer than 300 bp which mapped to the reference genome, but did not overlap with the human (resp. mouse) annotation.

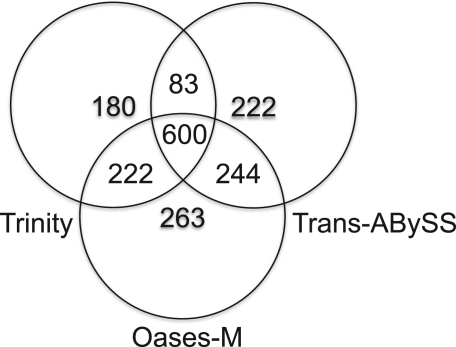

In Figure 4, the overlap of full length mouse transcripts reconstructed by the three methods is shown. It is interesting to note that although the results greatly overlap, the different assemblers succeeded in assembling different transcripts.

Fig. 4.

Venn Diagramm that compares mouse Ensembl transcripts reconstructed to full length by Trinity, Trans-AbySS and Oases-M for the mouse RNA-seq data.

3.8 Comparing de novo and reference-based assemblers

Oases and the other de novo assemblers were finally compared on the mouse data to a reference-based assembly algorithm, Cufflinks (Trapnell et al., 2010), on the mouse dataset. As could be expected, Cufflinks generally outperforms the de novo assembly algorithms, as it benefits from using the reference genome to anchor its assemblies (Fig. 3). Nonetheless, it is interesting to note that as expression level and therefore coverage depth go up, the gap narrows.

Beyond assembling more transcripts, it is also important to recover multiple isoforms for each gene. For each assembled transcript, the average number of additionally assembled transcripts from the same gene are, respectively, 1.21, 1.25, 1.01 and 1.56 for Oases, transABySS, Trinity and Cufflinks. Cufflinks performs better in that respect, whereas Trinity is less sensitive.

3.9 Runtime and memory

A de novo transcriptome assembly is a resource intensive task. Velvet uses multithreading but Oases currently does not. The complete merged assembly for human took ~3.2 h and 6.1 GB of peak memory on a 48 core AMD Opteron machine with 265 GB RAM. The merged assembly for mouse took ~10.3 h and 15.1 GB peak memory.

4 DISCUSSION

We have shown that merging different single k assemblies is beneficial, in concordance with previous work (Surget-Groba and Montoya-Burgos, 2010; Robertson et al., 2010). Oases employs dynamic cutoffs, where possible, to allow for a robust reconstruction with different k-values. However, detailed parameter optimization for Oases and trans-ABySS may lead to further improvements.

Overall, the de novo methods produced large numbers of misassemblies. Given the dynamic ranges involved, the exact parameter settings of these programs define a trade-off between sensitivity and accuracy. In these experiments, Oases tends to be more sensitive, Trinity more accurate. The correlation of small k-mer assemblies and misassembly rates suggests that homologies between genes are the main source of errors. As reads get longer, and coverage depths greater, sensitivity will only increase and users will probably avoid the shorter k-mer lengths for greater accuracy. Short k-mers will only be necessary to retrieve the very rare transcripts.

An independent but significant factor to these assemblies is read preprocessing, as read error removal has already been shown to have a significant impact in the context of de novo genome assembly (Smeds and Künster, 2011).

Interestingly, the comparison of reconstructed transcripts for the three de novo methods in Figure 4 reveals that each method outperforms the others on a separate set of transcripts. These differences in performance are probably due to the different strategies employed to remove errors. A more aggressive method, which discards more data, would presumably end up with many gaps on low expression data, whereas a more lenient algorithm would leave too many ambiguities at high coverage.

In particular, it appears that the performance of all the assemblers sometimes drops at very high coverage depths. This is probably linked to increased noise. Indeed, this drop is especially marked for transABySS, which, to our knowledge, is the only of the three de novo assemblers not to integrate dynamic filters which adapt with coverage depth.

Intriguingly, transABySS outperformed Trinity in our experiments, contrary to the observation of Yassour et al., (2011). This could not be due to the parameterization of Trinity, which cannot be parameterized apart from the insert length. Instead, the larger k range used for transABySS and the lower sequencing depth in our analyzed data sets may explain this discrepancy, as transABySS was shown to perform especially well for low to medium expressed genes.

Similarly, our experiments on mouse data show a bigger gap between Cufflinks and the de novo assemblers than observed by Yassour et al. (2011). In their work, the comparison was focused on the set of ‘oracle’ transcripts, which show sufficient coverage of exact k-mers in the reads. However, no such restriction was applied here and Cufflinks surpasses the de novo methods for low to medium expression ranges, where coverage is sparse.

In this study, we did not analyze strand-specific RNA-seq datasets. However, as these datasets become more available (Levin, 2010) Oases already supports this data. During the hashing phase, reverse complement sequences can be stored separately instead of being joined as the two strands of the same sequence.

5 CONCLUSION

Oases provides users with a robust pipeline to assemble unmapped RNA-seq reads into full length transcripts. Oases was designed to deal with the conditions of RNA-seq, namely uneven coverage and alternative splicing events.

Our results show how crucial it is to explore and understand the relevant conditions. Alternative splicing can significantly confound the assembly and has to be specifically addressed. Gene expression levels are a major factor determining the sensitivity of an algorithm. High coverage genes require more selective methods, whereas low coverage genes favor more sensitive algorithms. This is why exploring a range of k-mer lengths is key to success.

In the light of these results, Oases was designed to perform well overall by adapting to these varying conditions and succeeded in obtaining superior overall results compared to previously published RNA-seq de novo assemblers. Nonetheless, it also appears that merging assemblies from a diversity of algorithms could be beneficial. This is probably due to the dynamic range of all the variables, which prevent any single method from being systematically superior.

Finally, we examined the difference between de novo and reference-assisted assembly. In the presence of a well-assembled genome (typically human or mouse), the latter methods are generally at a significant advantage. Nonetheless, this gap reduces at high expression levels. This shows that the absence of an assembled genome can be largely compensated for provided sufficient read coverage.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to Cole Trapnell, Ali Mortazavi and Diane Trout for their help in obtaining the C2C12 dataset. Many thanks to Brian Haas for his patient testing of Oases, and to all the other users for their feedback. Thank you to Saket Navlakha and Benedict Paten for their proofreading and commentaries.

Funding: M.H.S. was supported by the International Max Planck Research School for Computational Biology and Scientific Computing. D.R.Z. and E.B. were funded by EMBL central funds. D.R.Z. is also funded by ENCODE grant 1U41HG004568-01, the NHGRI GENCODE subcontract (Prime: 1U54HG004555-01, Subaward: 0244-03) and the NHGRI ENCODE DAC grant (Prime: NHGRI 1U01HG004695-01, Subcontract: European Bioinformatics Institute).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Footnotes

†The authors wish it to be known that, in their opinion, the first two authors should be regarded as joint First Authors.

REFERENCES

- Birol I., et al. De novo transcriptome assembly with ABySS. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2872–2877. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blencowe B.J., et al. Current-generation high-throughput sequencing: deepening insights into mammalian transcriptomes. Gene. Dev. 2009;23:1379–1386. doi: 10.1101/gad.1788009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler J., et al. ALLPATHS: de novo assembly of whole-genome shotgun microreads. Genome Res. 2008;18:810–820. doi: 10.1101/gr.7337908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins L.J., et al. An approach to transcriptome analysis of non-model organisms using short-read sequences. Genome Inform. 2008;21:3–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denoeud F., et al. Annotating genomes with massive-scale RNA sequencing. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R175. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-12-r175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttman M., et al. Ab initio reconstruction of cell type-specific transcriptomes in mouse reveals the conserved multi-exonic structure of lincRNAs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:503–510. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heap G.A., et al. Genome-wide analysis of allelic expression imbalance in human primary cells by high-throughput transcriptome resequencing. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010;19:122–134. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heber S., et al. Splicing graphs and EST assembly problem. Bioinformatics. 2002;18(Suppl. 1):S181–S188. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.suppl_1.s181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson B.G., et al. Parallel short sequence assembly of transcriptomes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10(Suppl. 1):S14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-S1-S14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H., Wong W.H. Statistical inferences for isoform expression in RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1026–1032. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent W.J. BLAT–the BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Res. 2002;12:656–664. doi: 10.1101/gr.229202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. Generating consensus sequences from partial order multiple sequence alignment graphs. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:999–1008. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin J.Z. Comprehensive comparative analysis of strand-specific RNA sequencing methods. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:709–715. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin J., et al. Rnnotator: an automated de novo transcriptome assembly pipeline from stranded RNA-Seq reads. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:663. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortazavi A., et al. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-seq. Nat. Methods. 2008;5:621–628. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers E.W. The fragment assembly string graph. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(Suppl. 2):ii79–ii85. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice P., et al. EMBOSS: the European molecular biology open software suite. Trends Genet. 2000;16:276–277. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)02024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard H., et al. Prediction of alternative isoforms from exon expression levels in RNA-Seq experiments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e112. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson G., et al. De novo assembly and analysis of RNA-seq data. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:909–912. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson J.T., et al. ABySS: a parallel assembler for short read sequence data. Genome Res. 2009;19:1117–1123. doi: 10.1101/gr.089532.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeds L., Künster A. ConDetri – a content dependent read trimmer for illumina data. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26314. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sultan M., et al. A global view of gene activity and alternative splicing by deep sequencing of the human transcriptome. Science. 2008;321:956–960. doi: 10.1126/science.1160342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surget-Groba Y., Montoya-Burgos J.I. Optimization of de novo transcriptome assembly from next-generation sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1432–1440. doi: 10.1101/gr.103846.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C., et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:511–515. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakaguri H., et al. Full-malaria/parasites and full-arthropods: databases of full-length cDNAs of parasites and arthropods, update 2009. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D520–D525. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang E.T., et al. Alternative isoform regulation in human tissue transcriptomes. Nature. 2008;456:470–476. doi: 10.1038/nature07509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., et al. RNA-Seq: a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009;10:57–63. doi: 10.1038/nrg2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weese D., et al. RazerS–fast read mapping with sensitivity control. Genome Res. 2009;19:1646–1654. doi: 10.1101/gr.088823.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteford N., et al. An analysis of the feasibility of short read sequencing. Nulceic Acid Res. 2005;33:e171. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yassour M., et al. Ab initio construction of a eukaryotic transcriptome by massively parallel mRNA sequencing. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci., USA. 2009;106:3264–3269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812841106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yassour M., et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerbino D.R., Birney E. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res. 2008;18:821–829. doi: 10.1101/gr.074492.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerbino D.R., et al. Pebble and rock band: heuristic resolution of repeats and scaffolding in the velvet short-read de novo assembler. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8407. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.