Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Serious injury secondary to all terrain vehicle usage has been widely reported since the 1970s. All-terrain vehicles (ATV) or ‘quad bikes’ are four wheeled vehicles used for agricultural work, recreation and adventure sport. Data collected in the U.S. indicates that ATV related injury and fatality is increasing annually.

PRESENTATION OF CASES

This case series describes 3 cases of significant ATV related trauma in adults presenting to one regional hospital in the West of Ireland over a 12 month period.

DISCUSSION

Epidemiology, mechanisms of injury, spectrum of injury in adults and preventative measures to reduce the number of ATV related injuries and fatalities are discussed here with a review of the literature.

CONCLUSION

A paucity of research outside of North America is highlighted by this case series. Mandatory reporting of ATV related injury, educational, training and legislative measures are suggested as injury prevention strategies.

Keywords: ATV, All-terrain vehicle, Quad bike, Off road motor vehicle, Prevention of ATV injury, Adult trauma

1. Introduction

All-terrain vehicles (ATVs) are four wheeled vehicles which travel on low pressure tyres with engine sizes varying from 49 to 1000 cc. ATVs have an inherently unstable design with a narrow-wheel base, short turning radius, high centre of gravity and low tyre pressure to maximize manoeuverability. They travel at speeds of up to 120 km per hour or more depending on engine size and vehicle design. Injury and fatalities secondary to ATV use have been documented worldwide since their invention in Japan in the 1960s and subsequent introduction to the U.S. in the 1970s. They are in popular use in agricultural work due to their ability to handle a variety of terrain, light footprint and speed. ATVs have also gained popularity in competition racing, off road travel and recreation. They are classified in Ireland as ‘off road vehicles’ and legislation regarding appropriate driving licensing, insurance, vehicle standards regulations and concomitant use of a helmet/safety belt only applies to the use of these vehicles on public roads.1

2. Presentation of cases

Each of the cases, outlined in Table 1, describes off road ATV use. Two cases involved recreational use and one case illustrated agricultural operation. There was no use of helmets, safety belts or other protective equipment in any of the cases described and none of these patients had received training in the use of ATVs. The patient in each case was the sole driver and occupant of the ATV. One case resulted in fatality and the other two cases required emergency surgery with satisfactory post-operative recovery.

Table 1.

.

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of injury | 25 year old female Fall from ATV, driving on beach No helmet/safety belt Flexion–distraction of head from neck/torso witnessed by physician at scene |

22 year old male Fall from ATV, thrown 3 m landing on left side No helmet/safety belt Loss of consciousness × 2 mins and amnesia for event with persistent headache |

37 year old male farmer Crushed between ATV and wall for 5 min after losing control of ATV while driving inside a shed No helmet/safety belt Severe left upper quadrant pain with nausea and vomiting |

| Vitals on arrival | Guedel airway in situ Agonal asynchronous breaths BP: unrecordable HR: pulseless ECG: pulseless electrical activity Sp02: unrecordable Temp: 34.5 °C GCS: 3/15 Pupils: fixed and unreactive |

Airway intact breathing uncompromised BP:152/70 HR: 62 Sp02: 97% room air Respiratory rate: 15/min GCS: 15/15 |

Airway intact Breathing uncompromised BP: 131/69 HR: 80 Sp02: 96% room air Respiratory rate: 22/min GCS: 15/15 |

| Initial assessment & management | CPR continued on arrival Fluid resuscitation with crystalloids and O negative packed red blood cells Sinus tachycardia and BP 170/90 in response to CPR Chest drain inserted for clinical left pneumothorax Active blood loss from scalp laceration, epistaxis, haemoptysis and abdomen distended |

Superficial haematoma and swelling at left temporal region + haemotympanum Left clavicle tenderness Abdomen soft non tender with superficial abrasions Onset of vomiting with GCS drop to 13/15, 12 h after initial injury |

Abdomen soft with left upper quadrant tenderness without guarding/rigidity/rebound Patient remained stable with conservative medical management for 24 h but self discharged against medical advice He represented 5 days after his accident with worsening abdominal pain at which point he had developed hypovolemic shock and localised peritonism in the left upper quadrant. Hb dropped to 6.6 from 13.4 g/dL in the interim |

| Imaging |

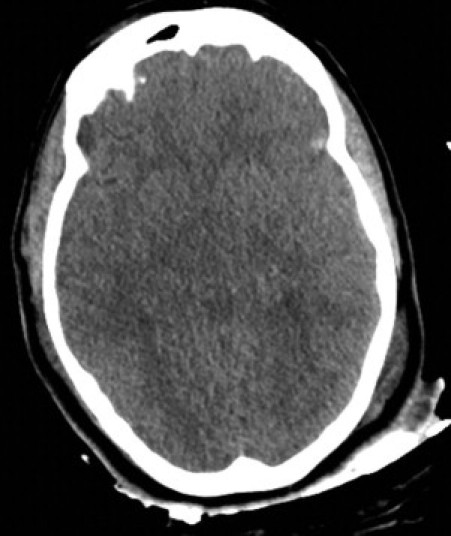

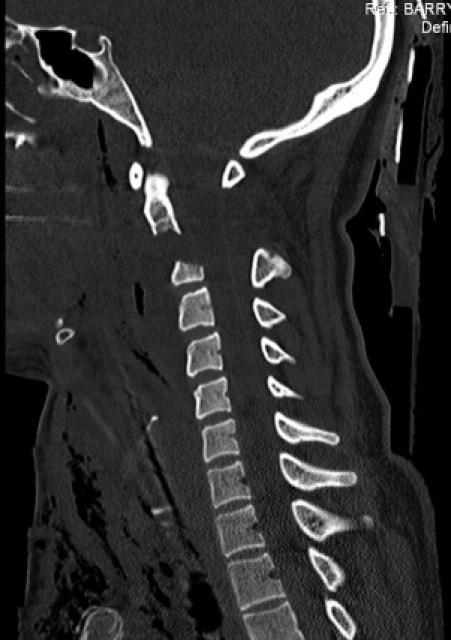

CT Brain (Fig. 1) Gross brain oedema with coning CT Spine (Fig. 2) Grossly displaced, distracted C2 fracture CT thorax/abdomen/pelvis (Fig. 3) Bilateral pneumothoraces, multiple left sided rib and clavicle fracture. Small bowel, mesenteric and hepatic lacerations |

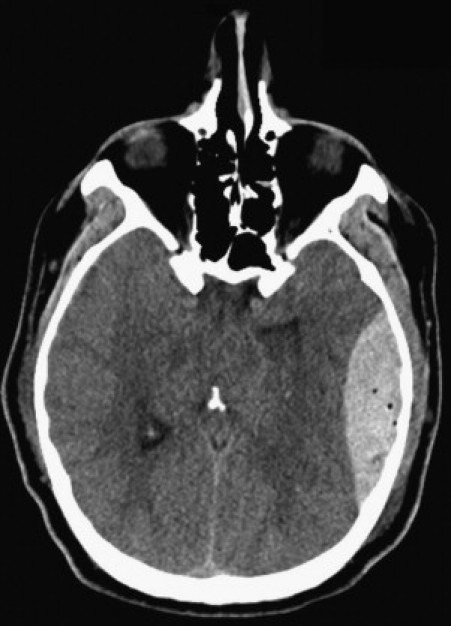

CT Brain (Fig. 4) Extradural haematoma left temporo-parietal area with brain oedema and 5 mm midline shift to right and undisplaced temporal fracture Chest/left shoulder X-ray Left clavicle fracture with inferior displacement of proximal fragment |

USS abdomen – initial presentation 5 cm diameter haematoma in the interpolar region of the spleen with crescentric fluid collection around the spleen. Normal renal and hepatic outlines and no free abdominal fluid CT abdomen – 5 days later (Fig. 5) Splenic rupture with a large intra and perisplenic haematoma and significant volume haemoperitoneum. |

| Operative intervention | Nil | Transferred to neurosurgical facility for left craniotomy with extradural haematoma evacuation | Laparotomy with splenectomy – severely lacerated spleen within a large haematoma and blood in abdominal cavity+++ |

| Outcome | Transferred to intensive care unit post CT imaging transfused total of 6 units of packed red blood cells 2nd cardiac arrest (pulseless electrical activity) and cushing response. RIP 2 h post admission |

Uneventful post op recovery Mild memory and concentration impairment with emotional liability on follow up cognitive assessment |

24 h ICU admission post op transfused total of 4 units of packed red blood cells Uneventful post op course Appropriate vaccination and antimicrobial prophylaxis initiated |

3. Discussion

3.1. Rate of injury

The rate of injury sustained specifically from ATV use is unknown in Ireland as annual figures compiled by the National Road Safety Authority group these injuries under the broader category of ‘motor cycle injuries’. A number of studies from the US and Canada demonstrate a gradual rise in the rates of ATV related injuries and deaths in recent years.2–4

3.2. Epidemiology

In each case described in this series, the injured party was the driver of the vehicle. 80–90% of injuries involve the driver of the ATV as opposed to a passenger.3,5,6 Risk factors for ATV related injury and death include male sex, age <18, white race, rural residence, intoxication, driving inexperience, recreational use of ATV as opposed to work related usage and large engine size.7 Large engine ATV production has increased threefold since 2003.8 These large engine vehicles can reach speeds of up to 120 km per hour and may weigh in excess of 230 kg.9 One case control study10 estimated a 0.9% increase in risk of ATV injury/death for every 1% increase in engine size. Paediatric injury and fatality from ATV use has been well described in the literature4,11 although they account for just 15% of ATV users.4 The average age of ATV related mortality is 28 years.9

3.3. Comparison with motorcycle trauma

Two retrospective studies comparing motorcycle trauma with ATV trauma have shown similar mortality and ATV riders were found to be significantly younger and more severely injured (as per comparison using the median injury severity score) with a higher incidence of head and neck injury (56% vs. 30%, p < 0.001).12

A recent study13 compared the risk of injury and death from ATV use to that of off road motorcycles or ‘dirt bikes’. The study involved more than 50,000 cases and showed both groups had similar injury severity scores. However unadjusted mortality was higher for ATV users (2.6% vs. 1.2%) and remained 1.51 fold higher after adjustment for factors such as gender, age, injury severity score, GCS and helmet use. Off road motorcycle users also had lower rates of ICU admission and ventilation compared with ATV users.

3.4. Mechanism of injury

The mechanisms of injury involved in our case series included fall from the ATV (Cases 1 and 2) and crush injury (Case 3). There are three main mechanisms of injury in ATV accidents as described by a New Zealand review of 218 cases – fall from ATV (48%), rollover (14%) and collision (31%) with a stationary/moving object.11 A retrospective review of 208 cases of ATV injuries in the US showed similar statistics – fall from ATV (32%), loss of stability/rollover (33%) and collision (27%).14 Rollover may occur when cornering or when travelling up or down a steep incline due to the unstable design and weight of these vehicles.

3.5. Injury classification

The mechanisms described above can inflict a wide variety of injuries. The cases described in this series are representative of three broad groups of injury: Head injury, musculoskeletal/orthopaedic injury and thoraco-abdominal Injury. The incidence of these injury types varies in the literature.7–9,15

3.5.1. Head injury

Head injuries are frequently fatal in ATV accidents.5,15 It has been reported that loss of consciousness occurs in over half of ATV related injuries.7 Almost one third of head injuries involved skull fractures and CT imaging demonstrated significant intracranial haemorrhage in one fifth of these head injury patients.16 While frequently less significant in the acute phase, injuries such as cerebral contusions, ophthalmic injuries and facial lacerations (described in 5–10%) have a potentially devastating impact on long term quality of life. The majority of ATV users do not own or use helmets and there is evidence that appropriate use of helmets is associated with a decreased incidence of traumatic brain injury, facial injury and subsequent mortality.17

3.5.2. Musculoskeletal/orthopaedic injury

Lower extremity fractures are the most common orthopaedic injury documented among adults and children.9 Of long bone injuries, femoral fractures are the most frequently reported followed hip dislocations, tibial-fibular fractures and partial foot amputations.15 Upper limb fractures are less common.18

Although rarely reported,9 vertebral fractures (as illustrated by Case 1 in the present series) cause significant morbidity and in the case of cervical fractures they are often incompatible with life. Thoracolumbar injury is most common16 but cervical fractures have greater negative impact on survival. Rollover is the commonest mechanism of injury in vertebral injury.

3.5.3. Thoraco-abdominal injury

Rates of compression injuries of the thorax and abdomen are comparable to that of head trauma in that they occur in over one half of ATV injuries.5,15 Pulmonary collapse or contusion, hepatic trauma and splenic disruption contribute significantly to ATV morbidity.7,15 While head injuries are frequently managed conservatively, disruption of thoracic and abdominal organs are more likely to require operative intervention in the emergency setting and frequently necessitate the transfer of patients to Level 1 trauma centres.

3.6. Prevention

In Ireland, as in many other countries, there is a paucity of legislation governing ATV usage in terms of licensing, minimum recommended age for operation and use of helmets and other safety equipment. Current legislation governs the use of ATVs on public roads only. The use of ATVs in the ‘off-road’ setting, for which they are designed, is therefore unregulated.

Evidence to support the efficacy of legislation in reducing injury and deaths from ATV usage is inconclusive. In the U.S. state of Georgia3 a progressive increase in the number of ATV related accidents was demonstrated in the years following the expiration of voluntary industry rider safety regulations in 1998. A 2006 randomized controlled trial demonstrated a significant reduction in work related childhood agricultural injuries after active dissemination of the North American Guidelines for Children's Agricultural Tasks (NAGCAT).19 The NAGCAT guidelines govern the capacity of children to use ATVs for agricultural work by reference to appropriate supervision and training requirements.

However, despite state specific US laws mandating helmet use, minimum operator age requirements and training prior to use of ATVs, the numbers of ATV related injuries and deaths continues to rise annually throughout the U.S. according to the Consumer Product Safety Commission database.4 One study specifically focused on the U.S. state of West Virginia due to its high rate of ATV related deaths. It demonstrated an initial rise in the rate of ATV related mortality (from 0.72 per 100,000 population in 2004 to 1.32 per 100,000 population in 2006) 2 years after the introduction of legislation designed to encourage safer ATV use.6 This was followed by a subsequent 34% reduction in mortality between 2006 and 2008,20 thought to be due to more effective law enforcement and ATV consumer education.

4. Conclusion

There is a lack of research outside North America regarding rates of ATV use, associated injury and deaths including the economic impact of these injuries and deaths. Mandatory reporting of ATV related injuries and fatalities would prove useful in defining the scale of the problem in individual countries, thus facilitating the development of evidence based injury prevention strategies. These strategies may include educational, training and legislative measures. There is no conclusive evidence thusfar to support the role of legislation in reducing ATV injury and fatality. The failure of current legislative efforts may be due to the commonplace use of ATVs in unregulated ‘off-road’ settings. In lieu of this, physicians may play a significant role by increasing public awareness of this growing problem. They may also encourage modification of unsafe ATV driver behaviour. ATV injury is associated with significant morbidity and mortality.12,13 Acute care physicians should be mindful of the spectrum of ATV related injuries experienced by adults, bearing in mind the high impact mechanisms of injury involved.

Conflict of interest statement

None.

Funding

None.

Consent

Written consent was obtained from each of the three patients included in our case series for publication of this case series and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contributions

Mr. K. Barry, Mr. W. Khan and Ms. A. Hogan contributed to case series editing and data collection.

Fig. 1.

Case 1: Axial image from a noncontrast CT brain study demonstrates gross generalized brain oedema with effacement of the basal cisterns and early coning.

Fig. 2.

Case 1: Sagittal reformatted CT image through the mid cervical spine demonstrates a grossly displaced C2 fracture.

Fig. 3.

Case 1: Axial CT image through the upper abdomen after IV contrast administration demonstrates a small contusion/laceration posteriorly in the right lobe of the liver, extensive free fluid suggesting a mesenteric tear and some free peritoneal air suggesting small bowel rupture.

Fig. 4.

Case 2: Axial noncontrast CT brain image shows a left sided lentiform acute extradural hematoma.

Fig. 5.

Case 3: Axial CT image with IV contrast through the upper abdomen shows haemoperitoneum and splenic rupture with mixed density hematoma within the spleen.

References

- 1.Road Traffic Act 2004 http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/2004/en/act/pub/0044/index.html.

- 2.Balthrop P.M., Nyland J., Roberts C.S. Risk factors and musculoskeletal injuries associated with all-terrain vehicle accidents. J Emerg Med. 2009;36(February (2)):121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.05.013. Epub 2007 October 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fonseca A.H., Ochsner M.G., Bromberg W.J., Gantt D. All-terrain vehicle injuries: are they dangerous? A 6-year experience at a level I trauma center after legislative regulations expired. Am Surg. 2005;71(November (11)):937–940. discussion 940-1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Consumer Product Safety Commission 2009. Annual report of all-terrain vehicle related deaths and injuries. http://www.atvsafety.gov/stats.html.

- 5.Hall A.J., Bixler D., Helmkamp J.C., Kraner J.C., Kaplan J.A. Fatal all-terrain vehicle crashes: injury types and alcohol use. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(April (4)):311–316. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) All-terrain vehicle fatalities-West Virginia, 1999–2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(March (12)):312–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balthrop P.M., Nyland J.A., Roberts C.S., Wallace J., Van Zyl R., Barber G. Orthopedic trauma from recreational all-terrain vehicle use in central Kentucky: a 6-year review. J Trauma. 2007;62(May (5)):1163–1170. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000229814.08289.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brandenburg M.A., Brown S.J., Archer P.A., Brandt E.N. All-terrain vehicle crash factors and associated injuries in patients presenting to a Regional Trauma Center. Journal of Trauma-Injury Infection & Critical Care. 2007;63(November (5)):994–999. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31814b91fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sawyer J.R., Kelly D.M., Kellum E., Warner W.C., Jr. Orthopaedic aspects of all-terrain vehicle-related injury. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19(April (4)):219–225. doi: 10.5435/00124635-201104000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodgers G.B., Adler P. Risk factors for all-terrain vehicle injuries: a national case–control study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153(June (11)):1112–1118. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.11.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cvijanovich N.Z., Cook L.J., Mann N.C., Dean J.M. A population-based assessment of pediatric all-terrain vehicle injuries. Pediatrics. 2001;108(September (3)):631–635. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.3.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Acosta J.A., Rodríguez P. Morbidity associated with four-wheel all-terrain vehicles and comparison with that of motorcycles. J Trauma. 2003;55(August (2)):282–284. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000080525.77566.ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Villegas C.V., Bowman S., Schneider E.B., Haut E.R., Stevens K.A., Efron D.T. The hazards of off road motor sports: Are four wheels better than two? Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2010;211(September (3)) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith L.M., Pittman M.A., Marr A.B., Swan K., Singh S., Akin S.J. Unsafe at any age: a retrospective review of all-terrain vehicle injuries in two level I trauma centers from 1995 to 2003. J Trauma. 2005;58(April (4)):783–788. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000158252.11002.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shah C.C., Ramakrishnaiah R.H., Bhutta S.T., Parnell-Beasley D.N., Greenberg B.S. Imaging findings in 512 children following all-terrain vehicle injuries. Pediatr Radiol. 2009;39(Jully (7)):677–684. doi: 10.1007/s00247-009-1213-x. Epub 2009 March 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finn M.A., MacDonald J.D. A population-based study of all-terrain vehicle-related head and spinal injuries. Neurosurgery. 2010;67(October (4)):993–997. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e3181f209db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merrigan T.L., Wall P.L., Smith H.L., Janus T.J., Sidwell R.A. The burden of unhelmeted and uninsured ATV drivers and passengers. Traffic Inj Prev. 2011;12(June (3)):251–255. doi: 10.1080/15389588.2011.561455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhutta S.T., Greenberg S.B., Fitch S.J., Parnell D. All-terrain vehicle injuries in children: injury patterns and prognostic implications. Pediatr Radiol. 2004;34(February (2)):130–133. doi: 10.1007/s00247-003-1085-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gadomski A., Ackerman S., Burdick P., Jenkins P. Efficacy of the North American guidelines for children's agricultural tasks in reducing childhood agricultural injuries. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:722. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.035428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cain L., Helmkamp J. Geographic and temporal comparisons of ATV deaths in West Virginia, 2000–2008. W V Med J. 2010;106(May–June (3)):26–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]