Abstract

Nox1, a homologue of gp91phox, the catalytic

moiety of the superoxide (O )-generating NADPH

oxidase of phagocytes, causes increased O

)-generating NADPH

oxidase of phagocytes, causes increased O generation, increased mitotic rate, cell transformation, and

tumorigenicity when expressed in NIH 3T3 fibroblasts. This study

explores the role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in regulating cell

growth and transformation by Nox1. H2O2

concentration increased ≈10-fold in Nox1-expressing cells, compared

with <2-fold increase in O

generation, increased mitotic rate, cell transformation, and

tumorigenicity when expressed in NIH 3T3 fibroblasts. This study

explores the role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in regulating cell

growth and transformation by Nox1. H2O2

concentration increased ≈10-fold in Nox1-expressing cells, compared

with <2-fold increase in O . When human catalase was

expressed in Nox1-expressing cells, H2O2

concentration decreased, and the cells reverted to a normal appearance,

the growth rate normalized, and cells no longer produced tumors in

athymic mice. A large number of genes, including many related to cell

cycle, growth, and cancer (but unrelated to oxidative stress), were

expressed in Nox1-expressing cells, and more than 60% of these

returned to normal levels on coexpression of catalase. Thus,

H2O2 in low concentrations functions as an

intracellular signal that triggers a genetic program related to cell

growth.

. When human catalase was

expressed in Nox1-expressing cells, H2O2

concentration decreased, and the cells reverted to a normal appearance,

the growth rate normalized, and cells no longer produced tumors in

athymic mice. A large number of genes, including many related to cell

cycle, growth, and cancer (but unrelated to oxidative stress), were

expressed in Nox1-expressing cells, and more than 60% of these

returned to normal levels on coexpression of catalase. Thus,

H2O2 in low concentrations functions as an

intracellular signal that triggers a genetic program related to cell

growth.

Whereas reactive oxygen

species (ROS) are classically thought of as cytotoxic and mutagenic or

as inducers of oxidative stress, recent evidence suggests that ROS play

a role in signal transduction. ROS are implicated in stimulation or

inhibition of cell proliferation, apoptosis, and cell

senescence (1–7). Whereas activated phagocytes produce very high

levels of O and

H2O2 that participate in

host defense, many other cell types also generate ROS, albeit generally

at lower levels (1, 8, 9).

and

H2O2 that participate in

host defense, many other cell types also generate ROS, albeit generally

at lower levels (1, 8, 9).

The function of non-phagocytic ROS generation is unclear, but in some

cases correlates with cell proliferation and activation of

growth-related signaling pathways. Intriguingly, significant ROS

generation is seen in cell lines derived from human cancers (9). Growth

factors including platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and epidermal

growth factor (EGF) trigger

H2O2 production (2, 10).

Signaling responses to PDGF include mitogen-activated protein kinase

activation, DNA synthesis, and chemotaxis, and these are inhibited when

the PDGF-stimulated rise in

H2O2 is blocked with

antioxidants (2). Similarly, Ras-transformed fibroblasts show elevated

O (11), and a role in mitogenic signaling was

proposed, because antioxidants that blocked O

(11), and a role in mitogenic signaling was

proposed, because antioxidants that blocked O generation also blocked DNA synthesis.

generation also blocked DNA synthesis.

The enzymatic origin of ROS in phagocytes is established, but its

origin in non-phagocytic cells is less clear. The phagocyte respiratory

burst oxidase, an NADPH-dependent multicomponent enzyme, generates

O , with secondary generation of

H2O2 (reviewed in refs. 12

and 13). The catalytic subunit, gp91phox, is dormant in

resting cells, but becomes activated by assembly with cytosolic

regulatory proteins. Whereas some ROS in non-phagocytes is of

mitochondrial origin (14, 15), ROS production in many cells is blocked

by inhibitors of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase. Such superficial

similarities with the phagocyte NADPH oxidase prompted us to search for

homologs of gp91phox. The first of these identified and

characterized was Nox1 (referring to NADPH oxidase, originally termed

Mox1; ref. 16). To date, five human homologs have been identified, with

additional homologs in rat, mouse, Caenorhabditis

elegans, and Drosophila (16–20).

, with secondary generation of

H2O2 (reviewed in refs. 12

and 13). The catalytic subunit, gp91phox, is dormant in

resting cells, but becomes activated by assembly with cytosolic

regulatory proteins. Whereas some ROS in non-phagocytes is of

mitochondrial origin (14, 15), ROS production in many cells is blocked

by inhibitors of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase. Such superficial

similarities with the phagocyte NADPH oxidase prompted us to search for

homologs of gp91phox. The first of these identified and

characterized was Nox1 (referring to NADPH oxidase, originally termed

Mox1; ref. 16). To date, five human homologs have been identified, with

additional homologs in rat, mouse, Caenorhabditis

elegans, and Drosophila (16–20).

Fibroblasts overexpressing Nox1 showed increased O ,

and, remarkably, exhibited a transformed phenotype, including increased

proliferation and aggressive tumor formation in athymic mice (16).

Herein, we have investigated the mechanism by which Nox1 induces cell

transformation and tumorigenicity. By manipulating intracellular levels

of H2O2 with Nox1 and

catalase, we demonstrate that

H2O2 functions as an

intracellular mediator regulating cell growth and transformation. In

addition, H2O2 triggers a

genetic program that results in altered expression of a large number of

genes, including many previously associated with transformation and

cancer, as well as regulation of the cell cycle and signal

transduction.

,

and, remarkably, exhibited a transformed phenotype, including increased

proliferation and aggressive tumor formation in athymic mice (16).

Herein, we have investigated the mechanism by which Nox1 induces cell

transformation and tumorigenicity. By manipulating intracellular levels

of H2O2 with Nox1 and

catalase, we demonstrate that

H2O2 functions as an

intracellular mediator regulating cell growth and transformation. In

addition, H2O2 triggers a

genetic program that results in altered expression of a large number of

genes, including many previously associated with transformation and

cancer, as well as regulation of the cell cycle and signal

transduction.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

DMEM was obtained from Fisher. FBS was from Atlanta Biologicals (Atlanta, GA). Calf serum, HindIII, penicillin, streptomycin, and zeocin were obtained from GIBCO (Grand Island, NY). The pZeoSV vector was from Invitrogen; puromycin, Hanks' buffered saline solution (HBSS), rabbit alkaline phosphatase conjugated secondary antibody, protease inhibitor mixture [4-(2-aminoethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoride/bestatin/trans-epoxysuccinyl-l-leucyl-amido(4-guanidino)betane/leupeptin/aprotinin], and PMSF were from Sigma. Antibody to human (h)catalase was purchased from Athens Research and Technology (Athens, GA). Dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFDA) was from Molecular Probes. Five- to six-week-old male athymic mice were from Charles River Breeding Laboratories. Human catalase cDNA was the kind gift of G. T. Mullenbach (Chiron).

Transfection of Human h-Catalase.

PCR was carried out by using as a template the cDNA for human catalase in the pCI-neo vector. The PCR product was ligated into the HindIII site of the pZeoSV vector. A clone was identified by restriction analysis that contained the catalase in the sense orientation (referred to as pZeoSV/catalase), and the insert was verified by DNA sequencing. Transfections were carried out by using Fugene 6 according to the manufacturer's instructions. After 2 days, the cells were split 1:27 into 10-cm plates, 0.4 mg zeocin/ml media was added, and cells were maintained until individual colonies formed. Colonies were isolated by using cloning cylinders, and the cells were removed from the plate with 50 μl 0.25% trypsin (wt/vol)/1 mM EDTA and placed in 2 ml of media in a 35-mm plate.

Maintenance of Cell Lines and Measurement of Cell Number.

Cell lines were maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2 in DMEM containing either 10% calf serum or 10% FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Puromycin was used as the selection antibiotic when making the Nox1 expression cell lines, and was maintained at 1 μg/ml during cell culture to maintain the selection pressure. YA28/Z4, ZC-1, YA28/Z3, and ZC-5 cells were maintained with or without 0.2 mg/ml zeocin. Cells were photographed by using a phase contrast microscope (Nikon, Model DIAPHOT). For growth curves, cells were plated in 6 well plates at ≈5 × 104 cells per well and cultured in media with 10% calf serum. Cells were treated with 0.25% trypsin (wt/vol)/1 mM EDTA, released by pipeting, and then counted with a hemacytometer.

Catalase Activity.

Confluent cells were released from plates as above, pelleted in a HermleZ180 M (Woodbridge, NJ) microcentrifuge set at maximum speed, and resuspended in 0.2 ml of PBS (pH 7.2) with 1:100 protease inhibitor mixture and 10 mM PMSF. While on ice, the suspension was sonicated briefly by using a probe sonicator on setting 2. Lysates containing 1 mg/ml protein (Bio-Rad Protein Assay) and 0.5% Triton X-100 were gently vortexed and microcentrifuged at maximum speed for 8 min. Fifty microliters of supernatant, 800 μl 10 mM KPO4 (pH 7.1), and either 50 μl H2O or 50 μl 10 mM sodium azide were combined on ice. The reaction was initiated by adding 100 μl of 60 mM H2O2, and was allowed to proceed on ice. At 2 min and 10 min, 100-μl aliquots were withdrawn and quenched in 5 ml of a solution containing 0.24 M H2SO4 and 2 mM FeSO4. KSCN (0.2 mM final) was added, and the absorbance of each sample was measured at 460 nm. Catalase activity was calculated as in ref. 21. Relative activity is expressed as a percentage of that in YA28 cells.

Western Blotting.

An aliquot of cell lysates (above) containing 30 μg of protein was diluted to 18 μl in PBS. Buffer (6 μl) containing 260 mM Tris (pH 8), 40% glycerol, 8% SDS, 4% 2-mercaptoethanol, and 0.002% bromophenol blue was added, and samples were heated 2 min at 100°C and loaded onto a 12% SDS gel. After electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose. Immunostaining was carried out as in ref. 22. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies to h-catalase were diluted 1:500 and incubated with the membrane for 13–18 hr. The anti-rabbit IgG from goat was diluted 1:5,000 and incubated for 2 hr with the membrane.

Measurement of Hydrogen Peroxide and Superoxide.

Relative concentrations of intracellular

H2O2 were determined as in

refs. 23 and 24. Confluent cells in 100-mm dishes (≈5–6 ×

106 cells) were washed with 6 ml HBSS and

released by using 0.25% trypsin (wt/vol)/1 mM EDTA, followed by the

addition of 5% FBS in HBSS. After pelleting, cells were resuspended in

5% FBS in HBSS and counted. Dichlorofluorescin diacetate was added to

a final concentration of 2 μM, and incubated for 1 hr in the dark at

room temperature. Dichlorofluorescein (DCF) fluorescence was determined

by using 0.5 × 106 cells per 3 ml 5% FBS

in HBSS by using a FACSCalibur from Becton Dickinson (excitation

wavelength, 488 nm; emission wavelength, 515–545 nm). Extracellular

H2O2 was measured as in

Ruch et al. (25). O was measured by

nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) reduction (16).

was measured by

nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) reduction (16).

Tumorigenesis in Athymic Mice.

Under metafane inhalational anesthesia, athymic mice were injected s.c. behind the neck with 1 × 106 cells in 200 μl of PBS. Tumor volume (V) was calculated according to: V (cm3) = [(width)2/2] × (length), by using calipers to measure the tumor dimensions.

Expression Profiling.

Poly(A) RNA was isolated from 1 × 107 cells by using Oligotex Direct mRNA Kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA). Double-stranded DNA was prepared by using Superscript Choice system (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Biotinylated RNA was synthesized by using BioArray High Yield RNA transcript labeling kit (Enzo Biochem). Biotinylated RNA was treated in a buffer composed of 200 mM Tris (pH 8.1), 500 mM potassium acetate, and 150 mM magnesium acetate for 35 min at 94°C. Affymetrix (Santa Clara, CA) Mu6500 arrays were hybridized with biotinylated RNA (15 μg/chip) for 20 hr at 45°C using the manufacturer's hybridization buffer. The Fluidic Station 400 from Affymetrix was used for washing and staining (with streptavidin-phycoerythrin). Arrays were scanned by using a Hewlett Packard GeneArray Scanner. Digitized image data were processed by using genechip expression analysis software (Affymetrix).

Reverse Transcription (RT)-PCR.

Total RNA was prepared from cell lines by using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA). Reverse transcription was performed on the total RNA by using the Advantage RT-for-PCR Kit (CLONTECH). PCR detection of Nox1 mRNA was carried out by using the primers ATATTTTGGAATTGCAGATGAACA and ATATTGAGGAAGAGACGGTAG.

Results

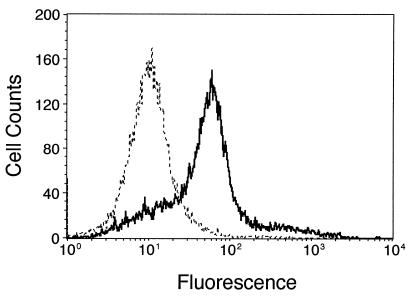

Nox1-Transfected Cells Have Increased H2O2 Levels.

By using several methods (spin trapping, lucigenin, and NBT reduction),

we previously showed that NIH 3T3 cells expressing Nox1 show a 1.5- to

2-fold increase in O levels (16), confirmed by using

NBT reduction in Table 1. In the previous

study, NBT reduction was ≈50% inhibited by superoxide dismutase

(SOD), indicating that part of the superoxide generation occurs

extracellularly (16). In addition, both cytoplasmic and mitochondrial

forms of aconitase showed diminished activity in Nox1-expressing cells,

suggesting that a portion of the superoxide generation also occurred

within the cell. Because

H2O2 is formed via

dismutation of O

levels (16), confirmed by using

NBT reduction in Table 1. In the previous

study, NBT reduction was ≈50% inhibited by superoxide dismutase

(SOD), indicating that part of the superoxide generation occurs

extracellularly (16). In addition, both cytoplasmic and mitochondrial

forms of aconitase showed diminished activity in Nox1-expressing cells,

suggesting that a portion of the superoxide generation also occurred

within the cell. Because

H2O2 is formed via

dismutation of O ,

H2O2 levels were also

measured herein by using flow cytometry of DCF fluorescence. Cells that

stably express Nox1 (YA28) showed ≈10-fold increased median

fluorescence compared with vector control (NEF2) cells (Fig.

1). This result corresponds to a

≈5-fold increase in the mean fluorescence (Table 1). The SOD mimetic

MnTBAP (100 μM) added to Nox1-expressing cells caused a 25% decrease

in NBT reduction and a 29% increase in DCF fluorescence, consistent

with dismutation of superoxide to form

H2O2. In addition, Cu-Zn

SOD (600 units/ml) increased the DCF fluorescence by ≈3-fold; these

data verify the use of these reagents in this cell system to monitor

O

,

H2O2 levels were also

measured herein by using flow cytometry of DCF fluorescence. Cells that

stably express Nox1 (YA28) showed ≈10-fold increased median

fluorescence compared with vector control (NEF2) cells (Fig.

1). This result corresponds to a

≈5-fold increase in the mean fluorescence (Table 1). The SOD mimetic

MnTBAP (100 μM) added to Nox1-expressing cells caused a 25% decrease

in NBT reduction and a 29% increase in DCF fluorescence, consistent

with dismutation of superoxide to form

H2O2. In addition, Cu-Zn

SOD (600 units/ml) increased the DCF fluorescence by ≈3-fold; these

data verify the use of these reagents in this cell system to monitor

O and

H2O2. Because we presume

that SOD did not enter the cell, it is also possible that the

extracellular SOD catalyzed the oxidation of DCF by way of bicarbonate

radical, which can be formed by Cu/Zn SOD plus

H2O2. Nevertheless,

H2O2 levels outside the

cell, detected by using homovanillic acid (25), were not consistently

affected by expression of Nox1 (not shown). Thus, Nox1 produces a

marked increase in intracellular

H2O2.

and

H2O2. Because we presume

that SOD did not enter the cell, it is also possible that the

extracellular SOD catalyzed the oxidation of DCF by way of bicarbonate

radical, which can be formed by Cu/Zn SOD plus

H2O2. Nevertheless,

H2O2 levels outside the

cell, detected by using homovanillic acid (25), were not consistently

affected by expression of Nox1 (not shown). Thus, Nox1 produces a

marked increase in intracellular

H2O2.

Table 1.

ROS generation in NIH 3T3 cells expressing Nox1 and Nox1 plus h-catalase

| Cell line | Nox1 | h-catalase | Mean DCF fluorescence per cell | NBT reduced, nmol/20 min/106 cells |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEF2 | − | − | 9 ± 0.7 | 19.1 ± 0.5 |

| YA28 | + | − | 50 ± 5.2 | 28.7 ± 5.1 |

| YA28/Z4 | + | − | 41 ± 0.4 | 35.1 ± 2.9 |

| YA28/Z3 | + | − | 67 ± 1.0 | 76.2 ± 29 |

| ZC-1 | + | + | 25 ± 0.2 | 32.6 ± 3.2 |

| ZC-5 | + | + | 33 ± 0.5 | 30.5 ± 4.4 |

DCF fluorescence (a measure of H2O2) and

NBT reduction (a measure of O ) in the indicated cell

lines were measured as in Materials and Methods. The mean

and SE of three independent measurements are shown.

) in the indicated cell

lines were measured as in Materials and Methods. The mean

and SE of three independent measurements are shown.

Figure 1.

Expression of Nox1 increases intracellular H2O2. Cells were incubated with 2 μM dichlorofluorescin diacetate, and fluorescence and cell number were determined by flow cytometry. The dashed line indicates vector control (NEF2) cells, and the solid line indicates cells expressing Nox1 (YA28).

Expression of h-Catalase in Nox1-Expressing Cells.

YA28 cells expressing Nox1 were transfected with the pZeoSV/catalase vector containing the h-catalase or with the empty vector. Twelve cell lines were obtained from the catalase transfections, and these were analyzed for catalase expression. Two of these (ZC-1 and ZC-5) showed significant expression of h-catalase protein (Fig. 2A), which is distinguished from the mouse catalase based on its slightly larger size, whereas one line (YA28/Z3) failed to express h-catalase, and was used as a negative control line along with the YA28/Z4 cells, which are YA28 cells transfected with the empty vector. Based on the density of the bands compared with the mouse enzyme, ZC-1 and ZC-5 cells express roughly equivalent quantities of the mouse and h-catalase. Expression data are consistent with catalase activity measurements (Fig. 2B), which show that both ZC-1 and ZC-5 have 2- to 3-fold increased catalase activity compared with control cell lines. The expression of Nox1 was unaffected by overexpression of h-catalase (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Catalase expression and activity in cells transfected with Nox1 and h-catalase. (A) Catalase expression was determined in the indicated cell lines by Western blotting by using an antibody that recognizes both the human (upper band) and mouse (lower band) catalase. Caco-2 cells serve as a positive control for expression of h-catalase. (B) Catalytic activity (100% = 6.5 units/mg cell protein) was assayed in cell lysates. The mean and SE of 4–25 determinations is shown. (C) Reverse transcription–PCR demonstrates Nox1 expression. G3PDH (glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase) serves as a loading control.

Catalase Overexpression Decreases H2O2 Levels in Nox1-Expressing Cells.

Cell lines were examined for

H2O2 levels by using DCF

fluorescence as in Fig. 1, and data are summarized in Table 1. Cell

lines that express Nox1 alone show an increase in mean DCF fluorescence

of 5- to 7-fold, compared with control cells. Expression of h-catalase

in ZC-1 and ZC-5 cells, while failing to restore DCF fluorescence to

normal levels, decreases mean DCF fluorescence by about 50%.

H2O2 levels in YA28/Z4

and YA28/Z3 cells (i.e., vector control cells) were not appreciably

affected, compared with YA28 cells. In contrast, there was no

consistent change in the O levels in cells

expressing h-catalase, compared with the parent Nox1-expressing cells

(Table 1).

levels in cells

expressing h-catalase, compared with the parent Nox1-expressing cells

(Table 1).

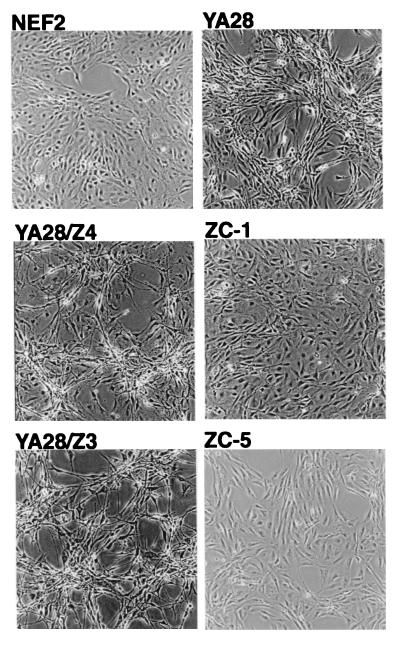

Catalase Overexpression Reverses the Transformed Phenotype of Nox1-Expressing Cells.

As shown previously (16), cells that overexpress Nox1 show a characteristic transformed appearance, with focus formation and loss of contact inhibition (Fig. 3 Upper). This transformed appearance is maintained in the vector control cell lines (YA28/Z4 and YA28/Z3) that do not overexpress h-catalase (Fig. 3). However, in YA28 cells that overexpress h-catalase (ZC-1 and ZC-3), there was a reversion to a normal appearance that is indistinguishable from that of the NEF2 cells that do not express Nox1.

Figure 3.

Effect of Nox1 and catalase on the transformed appearance of NIH 3T3 cells. Cell lines that do not (NEF2) or do (YA28, YA28/Z4, YA28/Z3, ZC-1, ZC-5) express Nox1. Lines that express catalase: ZC-1 and ZC-5. (×100.)

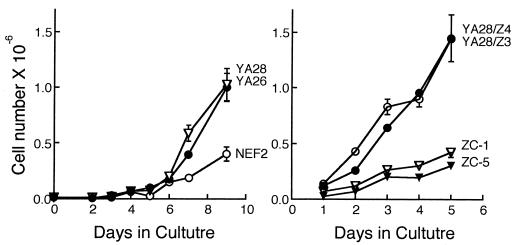

Catalase Overexpression Decreases the Growth Rate of Nox1-Expressing Cells.

As shown previously (16), YA26 and YA28 cells that overexpress Nox1 showed a 2- to 3-fold increase in growth rates in culture compared with control cells (Fig. 4A). Overexpression of h-catalase resulted in a decrease in growth rate to near control levels, whereas vector control lines (YA28/Z4 and YA28/Z3) that failed to suppress H2O2 levels showed high growth rates that were comparable to those of the parent Nox1-expressing cell line (Fig. 4). Consistent with H2O2 as the relevant growth stimulatory signal, addition of 1 μM H2O2 to the cell culture resulted in a 50% increase in cell number after 4 days.

Figure 4.

Effect of Nox1 and catalase on proliferation of NIH 3T3 cells. Cell lines are as in Fig. 3. Bars show the range of cell counts of duplicate cultures.

Catalase Overexpression Prevents Tumor Formation by Nox1-Expressing Cells.

Tumorigenicity of Nox1 and h-catalase-overexpressing cells was evaluated by tumor growth in athymic mice. As shown in Table 2, YA28 cells that overexpress Nox1 formed tumors within 14 days in athymic mice, whereas control (NEF2) cells fail to form tumors by 30 days, confirming our earlier study (16). Nox1-expressing cells that also express h-catalase (ZC-1 and ZC-5) behaved like cells that did not express Nox1, failing to form tumors by 30 days, whereas the vector control cell lines (YA28/Z3 and YA28/Z4) that did not overexpress catalase but did express Nox1 produced aggressive tumors that were indistinguishable from those produced by the parent Nox1-expressing cell line.

Table 2.

Effect of Nox1 and h-catalase on tumorigenicity of NIH 3T3 cells

| Cell line | Nox1 | h-catalase | Mice injected, number | Mice in which tumors formed, no. (%) | Tumor volume, cm3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEF2 | − | − | 4 | 0 (0%) | — |

| YA28 | + | − | 25 | 24 (96%) | 2.2 ± 1.4 |

| YA28/Z4 | + | − | 5 | 5 (100%) | 1.9 ± 0.9 |

| YA28/Z3 | + | − | 5 | 5 (100%) | 4.5 ± 0.7 |

| ZC-1 | + | + | 5 | 0 (0%) | — |

| ZC-5 | + | + | 5 | 0 (0%) | — |

Cell line designations are as in Table 1. The mean tumor volume ± standard error 25 days after injection of cells is indicated.

Effects of Nox1 on Gene Expression, and Reversion of Expression Changes by Catalase.

The effect of Nox1 and h-catalase on mRNA levels was evaluated by using the Affymetrix Mu6500 DNA microarray, which queries the expression of 6,500 genes. Because Nox1 causes increased mitogenic rate, transformed appearance and tumorigenicity, and because h-catalase reverts these phenotypes, we focused on genes whose expression is increased or decreased with Nox1 and whose expression is reverted toward normal on h-catalase expression. This group represents genes whose expression is regulated directly or indirectly by H2O2, and these are candidates for a role in mitogenesis and transformation. Approximately 200 genes increased or decreased their expression by 2.5-fold or more in YA28 cells compared with NEF2 cells. Expression of ≈70% of these genes reverted to normal or near normal levels in ZC-5 cells that overexpress h-catalase. Examples of some of these genes are shown in Table 3, which includes genes the expression of which may relate to regulation of cell division or tumorigenesis, including genes related to cell cycle, signaling proteins, and proteins whose occurrence or activity has been correlated previously with human cancers. Of the 19 genes in these categories that are regulated by Nox1, most reverted to near basal levels by h-catalase. Table 4 overviews expression changes induced by Nox1 in 24 functional categories of genes, and includes the number in each category changed by Nox1 and the number of these that are reverted to near normal levels by catalase.

Table 3.

Effect of Nox1 and catalase on expression of cell cycle and tumor-related genes

| Protein or gene | Fold increase or decrease

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Nox1 vs. control | Nox1/catalase vs. Nox1 | |

| Tumor-associated/tumorigenesis | ||

| Ecotropic viral integration site 2 (Evi-2) | ↑ 15, 17 | ↓ 16, 17 |

| MoMuL V-like endogenous provirus | ↑ 4.2, 14 | ↓ 4.1, 12 |

| L6 Ag | ↑ 2.3, 3.1 | ↓ 3.5, 4.3 |

| Stromelysin-3 | ↓ 1.6, 4.5 | ↑ 1, 4.8 |

| Membrane-type matrix metalloproteinase | ↓ 2.2, 6.6 | ↑ 3.6, 12 |

| Haptoglobin | ↓ 3.3, 4.2 | ↑ 1, 4.9 |

| Transin-1 (tromelysin-1) | ↓ 4.4, 10 | ↑ 1, 2.4 |

| Growth factor/cytokine | ||

| Epiregulin | ↑ 7.7, 11 | ↓ 6.0, 7.6 |

| Hepatoma transmembrane kinase ligand | ↑ 3.7, 8.3 | ↓ 2.0, 17 |

| New member PDGF/VEGT family growth factors | ↓ 2.2, 2.9 | ↑ 13, 15 |

| Preproendothelin-1 (ET-1) | ↓ 3.0, 6.6 | ↑ 1, 3.7 |

| Signaling | ||

| MAPKK6 | ↑ 3.2, 7.7 | |

| Calcineurin catalytic subunit (PP2B) | ↑ 2.1, 2.5 | ↓ 1, 2.8 |

| Zipper protein kinase | ↑ 1.3, 3.4 | |

| Protein-tyrosine kinase substrate p36 | ↑ 1.5, 3.3 | ↓ 2.5, 3.3 |

| pre-PDGF receptor | ↓ 2.5, 3.7 | ↑ 2.1, 5.2 |

| Serum-inducible kinase | ↓ 3.0, 6.8 | ↑ 3.0, 5.2 |

| Cell cycle | ||

| Cyclin-like protein (Cyl-1) | ↑ 2.5, 3.2 | ↓ 3.8, 7.2 |

| Cyclin G | ↑ 2.1, 3.8 | ↓ 1.6, 4.2 |

mRNA levels were evaluated using a DNA microarray, as described in Materials and Methods. Fold increase (↑) or decrease (↓) in mRNA level is indicated. The values of two independent experiments are shown.

Table 4.

Effects of Nox1 and catalase on gene expression

| Category of gene | No. changed by Nox1 | No. normalized by catalase |

|---|---|---|

| Apoptosis | 6 | 2 |

| Cell adhesion | 9 | 7 |

| Cell cycle | 2 | 2 |

| Chaperones/heat shock proteins | 3 | 3 |

| Cytoskeletal/structural proteins | 12 | 6 |

| Development/differentiation | 6 | 3 |

| DNA repair | 1 | 1 |

| Endocrine | 4 | 2 |

| Extracellular matrix | 8 | 7 |

| Endocytosis | 1 | 1 |

| Growth factor/cytokine | 4 | 4 |

| Inflammation/immune function | 4 | 3 |

| Lipid binding/transfer proteins | 5 | 2 |

| Enzymes of metabolism | 24 | 12 |

| Neuronal | 2 | 2 |

| Protein degradation | 7 | 5 |

| Protein synthesis | 15 | 7 |

| RNA processing | 4 | 3 |

| Signaling | 6 | 4 |

| Transcription | 19 | 9 |

| Replication | 1 | 0 |

| Transport | 7 | 3 |

| Tumor-associated/tumorigenesis | 7 | 7 |

| Function unknown/miscellaneous | 5 | 4 |

mRNA levels were evaluated using a DNA microarray, as in Materials and Methods. mRNAs whose expression in NIH 3T3 cells is affected by Nox1 overexpression are subdivided into functional categories. The number of genes in each category whose expression is increased or decreased by 2.5-fold or more is shown in the second column. The number of these same mRNAs whose expression was then normalized by coexpression of h-catalase is shown in the third column.

Discussion

NIH 3T3 cells that stably express Nox1 show a transformed

phenotype, with loss of contact inhibition and aggressive tumor

formation in athymic mice (16). Two explanations can be offered for the

mechanism by which ROS induces the transformed phenotype. First,

reactive oxygen generated by Nox1 may be mutagenic, causing the

transformed phenotype by producing mutations in bona fide oncogenes or

tumor suppressors. Alternatively, Nox1-generated ROS might function as

an intracellular signal, inducing a growth-related genetic program. If

the first mechanism is correct, then the transformed phenotype is

expected to be stable, and will not be affected by removal of ROS.

However, if ROS function as a growth signal, then their removal should

reverse the transformed phenotype. Accumulating (albeit controversial)

evidence has implicated ROS in signaling related to cell proliferation

and transformation (2, 11, 16, 26). Conflicting evidence points to

either O or

H2O2 in mitogenic

regulation and transformation (1, 26–30). Ras-transformed fibroblasts

overproduce O

or

H2O2 in mitogenic

regulation and transformation (1, 26–30). Ras-transformed fibroblasts

overproduce O , and this overproduction is correlated

with activation of mitogenic signaling pathways (11). Loss of SOD

(which should elevate O

, and this overproduction is correlated

with activation of mitogenic signaling pathways (11). Loss of SOD

(which should elevate O levels) has also been

correlated with a cancer phenotype, and overexpression of SOD leads to

reversion of transformation (28–30). On the other hand,

H2O2 is generated in

response to the growth factors epidermal growth factor and PDGF, and is

linked to growth-related signaling (2, 10). The present studies were

undertaken to investigate whether the phenotype of Nox1-transfected

cells is reversible, thereby implicating ROS as a signal molecule, and,

if so, to identify whether the relevant signal is O

levels) has also been

correlated with a cancer phenotype, and overexpression of SOD leads to

reversion of transformation (28–30). On the other hand,

H2O2 is generated in

response to the growth factors epidermal growth factor and PDGF, and is

linked to growth-related signaling (2, 10). The present studies were

undertaken to investigate whether the phenotype of Nox1-transfected

cells is reversible, thereby implicating ROS as a signal molecule, and,

if so, to identify whether the relevant signal is O or H2O2.

or H2O2.

Superoxide generation is modestly increased in cells expressing Nox1,

despite a marked overexpression of Nox1 mRNA (16). Aconitase activity

was also decreased by 20–25%, consistent with intracellular exposure

of the enzyme to O . Herein, we report that

Nox1-expressing NIH 3T3 cells produce 5- to 10-fold higher levels of

H2O2 than do control cells,

based on DCF fluorescence. Because binding sites for the prosthetic

groups NADPH, FAD, and heme are nearly identical to those of

gp91phox (17), we presume that the enzyme like the phagocyte

oxidase generates O

. Herein, we report that

Nox1-expressing NIH 3T3 cells produce 5- to 10-fold higher levels of

H2O2 than do control cells,

based on DCF fluorescence. Because binding sites for the prosthetic

groups NADPH, FAD, and heme are nearly identical to those of

gp91phox (17), we presume that the enzyme like the phagocyte

oxidase generates O directly, and that the observed

H2O2 originates from

dismutation of O

directly, and that the observed

H2O2 originates from

dismutation of O .

.

We show herein that h-catalase expressed in Nox1-expressing cells

lowers intracellular H2O2,

and that lowered H2O2

normalizes the phenotype of these cells in terms of transformed

appearance, growth rate in culture, and tumorigenicity in athymic mice.

Normally, H2O2 is

metabolized by catalase and cellular peroxidases, limiting its

lifetime. H2O2-metabolizing

activities, however, must be partially rate limiting, because

H2O2 accumulates on Nox1

overexpression and diminishes with catalase overexpression. Thus, the

activity of endogenous

H2O2-metabolizing enzymes

in these cells is well suited to permit

H2O2 levels to fluctuate

when production is increased, a necessary condition for function as a

signal. In contrast, catalase failed to affect cellular generation of

O . These data do not eliminate a cosignaling role

for O

. These data do not eliminate a cosignaling role

for O . For example, overexpression of Mn SOD or

Cu/Zn SOD in NIH 3T3 cells decreased cell proliferation (31, 32).

However, SOD overexpression perturbs both O

. For example, overexpression of Mn SOD or

Cu/Zn SOD in NIH 3T3 cells decreased cell proliferation (31, 32).

However, SOD overexpression perturbs both O and

H2O2 levels, and

SOD-induced H2O2 was

associated with cell senescence in the latter study (32). Perhaps

related to these studies, overexpression of either Mn SOD or Cu/Zn

SOD in Nox1-expressing cells was cytotoxic, and transfected cell lines

failed to survive (R.S.A., unpublished work). The present studies

complement earlier ones that collectively strongly implicate

H2O2 as a mediator of

normal cell proliferation: endogenous Nox1 is induced along

with increased ROS in vascular smooth muscle cells by the growth factor

PDGF, and decreased expression of endogenous Nox1 (using

antisense DNA) decreases ROS levels and inhibits serum-dependent cell

proliferation (16).

and

H2O2 levels, and

SOD-induced H2O2 was

associated with cell senescence in the latter study (32). Perhaps

related to these studies, overexpression of either Mn SOD or Cu/Zn

SOD in Nox1-expressing cells was cytotoxic, and transfected cell lines

failed to survive (R.S.A., unpublished work). The present studies

complement earlier ones that collectively strongly implicate

H2O2 as a mediator of

normal cell proliferation: endogenous Nox1 is induced along

with increased ROS in vascular smooth muscle cells by the growth factor

PDGF, and decreased expression of endogenous Nox1 (using

antisense DNA) decreases ROS levels and inhibits serum-dependent cell

proliferation (16).

Although the effects of ROS on cells are complex, our data are consistent with some earlier studies that showed a role for H2O2 in cell division. A low concentration of exogenously added H2O2 caused a modest increase in proliferation of BHK-21 and human prostate cells, whereas higher levels resulted in slowed growth, cell cycle arrest, and/or apoptosis (26, 33). Whereas H2O2 is membrane permeant and should enter the cell, metabolism will undoubtedly alter cellular levels over time, complicating interpretations and causing mixed responses that depend on time and concentration. This metabolism may account for the relatively small growth response of cells to added H2O2. In contrast, Nox1 continuously elevates the steady state concentration of H2O2, permitting an unadulterated mitogenic response.

The target(s) in the cell for

H2O2 that relate to growth

and transformation are not clear. p42/p44 mitogen-activated protein

kinase (MAPK); p38 MAPK; p70S6k; signal

transducers and activators of transcription (STAT) Akt/protein kinase

B; and phospholipase D signaling pathways are all activated by reactive

oxygen (34–38), but, in some cases, activation is indirect (39, 40). A

direct effect is on protein tyrosine phosphatase-1B (PTP-1B), which is

inhibited by oxidation of an active site thiol by O and H2O2 (41, 42), leading

to increased phosphotyrosine on many cell proteins. However,

O

and H2O2 (41, 42), leading

to increased phosphotyrosine on many cell proteins. However,

O is ≈10-fold kinetically more efficient than

H2O2 in activating PTP-1B

(42). Thus, reversal of the transformed phenotype with catalase is more

consistent with a pathway other than PTP-1B. A variety of other targets

can also be affected by ROS, including transcription factors such as

NF-κB (43), activator protein-1 (AP1; ref. 44), and p53 (45).

Whatever the proximal target(s),

H2O2 reprograms the cell's

expression of enzymes and other proteins. DNA microarray experiments

(Tables 3 and 4) indicate that ≈2% of 6,500 genes queried are

regulated by H2O2.

is ≈10-fold kinetically more efficient than

H2O2 in activating PTP-1B

(42). Thus, reversal of the transformed phenotype with catalase is more

consistent with a pathway other than PTP-1B. A variety of other targets

can also be affected by ROS, including transcription factors such as

NF-κB (43), activator protein-1 (AP1; ref. 44), and p53 (45).

Whatever the proximal target(s),

H2O2 reprograms the cell's

expression of enzymes and other proteins. DNA microarray experiments

(Tables 3 and 4) indicate that ≈2% of 6,500 genes queried are

regulated by H2O2.

Surprisingly, unlike the response of bacteria (46, 47) or yeast (48) to oxidative insult, few if any of the expression changes were related to oxidative defense or stress. Proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae induced by H2O2 (49) are summarized in Table 5. Escherichia coli exposed to oxidative insult induce functionally similar proteins, many of which are also induced by heat and other stress (50). In contrast, few if any functional analogs of these proteins are induced in Nox1-transfected cells (Table 5). Rather, many of the changes were in proteins related to the cell cycle, signal transduction, and transcription (Tables 3 and 4), indicating that H2O2 in the quantities produced triggers a highly specific genetic program that is distinct from a stress response per se. H2O2-induced changes in some of these proteins may participate in regulation of cell proliferation and induction of the transformed phenotype. These studies may have direct implications for understanding the role of reactive oxygen in cancer and other diseases of cellular hyperproliferation.

Table 5.

Effect of Nox1 on expression of stress-related proteins

| Protein | Fold change

|

|

|---|---|---|

| NIH 3T3 Nox1 vs. control | Yeast ± H2O2 | |

| Oxidative stress | ||

| Catalase | NC | ↑ 14.7 |

| SOD1 | NC | ↑ 4.3 |

| SOD2 | NC | ↑ 5.9 |

| SOD3 | NC | — |

| Glutathione reductase | — | ↑ 2.1 |

| Thioredoxin reductase* | NC | ↑ 12.2 |

| Thioredoxin* | NC | ↑ 11.5 |

| Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase | NC | ↑ 2 |

| Chaperones/heat shock proteins | ||

| Mammalian | ||

| Osmotic stress protein 94 | ↑ 3.2, 3.3 | — |

| HSP-25* | NC | — |

| HSP-47 | ↓ 2.4, 2.5 | — |

| HSP-70 | NC | — |

| HSP-E71 | NC | — |

| HSP-84 | NC | — |

| HSP-90α* | NC | — |

| DNAJ protein homolog HSJ1* | ↓ 2.1, 3.1 | — |

| HSP90-β* | NC | — |

| Yeast | ||

| DDR48 | — | ↑ 2.3 |

| HSP104 | — | ↑ 14.9 |

| HSP12 | — | ↑ 10 |

| HSP26 | — | ↑ >5 |

| HSP42 | — | ↑ 4 |

| HSP82 | — | ↑ 2.3 |

| PDI1 | — | ↑ 2.8 |

| SSA1 | — | ↑ 2.7 |

| SSA2 | — | ↓ 3 |

| SSA3 | — | ↑ 4.2 |

In the column labeled “NIH 3T3 Nox1 vs. control,” the fold increase (↑) or decrease (↓) in mRNA level for the indicated protein was evaluated in Nox1-transfected (YA-28) cells compared with control (Nef-2) cells using a DNA microarray, as described in Materials and Methods. In the column labeled “Yeast ± H2O2,” the increase or decrease in protein level in yeast in the presence or absence of H2O2 is shown. Yeast data are taken from ref. 50.

Reported as “similar to” the indicated gene in the Affymetrix database. For Nox1 vs. control cells, the values of the two independent experiments are shown. NC, No change.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jason Grayson and Joe Blattman in the Ahmed lab for help with flow cytometry. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant CA84138.

Abbreviations

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- HBSS

Hanks' buffered saline solution

- DCF

dichlorofluorescein

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- PDGF

platelet-derived growth factor

- NBT

nitroblue tetrazolium

- h

human

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Burdon R. Free Radical Biol Med. 1995;18:775–794. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)00198-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sundaresan M, Yu Z-X, Ferrans V J, Irani K, Finkel T. Science. 1995;270:296–299. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5234.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen Q M. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;908:111–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bladier C, Wolvetang E J, Hutchinson P, de Haan J B, Kola I. Cell Growth Differ. 1997;8:589–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murrell G A, Francis M J, Bromley L. Biochem J. 1990;265:659–665. doi: 10.1042/bj2650659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shibanuma M, Arata S, Murata M, Nose K. Exp Cell Res. 1995;218:132–136. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gansauge S, Gansauge F, Gause H, Poch B, Schoenberg M H, Beger H G. FEBS Lett. 1997;404:6–10. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cross A R, Jones O T G. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1057:281–298. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(05)80140-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Szatrowski T, Nathan C. Cancer Res. 1991;51:794–798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bae Y S, Kang S W, Seo M S, Baines I C, Tekle E, Chock P B, Rhee S G. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:217–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Irani K, Xia Y, Zweier J, Sollott S, Der C, Rearon E, Sundaresan M, Finkel T, Goldschmidt-Clermont P. Science. 1997;275:1649–1652. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5306.1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Babior B M. Curr Opin Hematol. 1995;2:55–60. doi: 10.1097/00062752-199502010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Segal A W, Shatwell K P. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;832:215–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb46249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams M, Van Remmen H, Conrad C, Huang T, Epstein C, Richardson A. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:28510–28515. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.28510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schulze-Osthoff K, Bakker A C, Vanhaesebroeck B, Beyaert R, Jacob W A, Fiers W. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:5317–5323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suh Y-A, Arnold R S, Lassegue B, Shi J, Xu X, Sorescu D, Chung A B, Griendling K K, Lambeth J D. Nature (London) 1999;401:79–82. doi: 10.1038/43459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lambeth J D, Cheng G, Arnold R S, Edens W E. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:459–461. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01658-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dupuy C, Ohayon R, Valent A, Noe-Hudson M, Dee D, Virion A. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:37265–37269. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.37265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Deken X, Wang D, Many M C, Costagliola S, Libert F, Vassart G, Dumont J E, Miot F. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:23227–23233. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000916200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geiszt M, Kopp J B, Várnai P, Leto T L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:8010–8014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.130135897. . (First Published June 27, 2000; 10.1073/pnas.130135897) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen G, Kim M, Ogwu V. J Neurosci Methods. 1996;67:53–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blake M S, Johnston K H, Russell-Jones G J, Gotschich E C. Anal Biochem. 1984;136:175–179. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(84)90320-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ubezio P, Civoli F. Free Radical Biol Med. 1994;16:509–516. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)90129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carter W O, Narayanan P K, Robinson J P. J Leukocyte Biol. 1994;55:253–258. doi: 10.1002/jlb.55.2.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruch W, Cooper P H, Baggiolini M. J Immunol Methods. 1983;63:347–357. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(83)80008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burdon R H. Biochem Soc Trans. 1996;24:1028–1032. doi: 10.1042/bst0241028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Egner P, Kensler T. Carcinogenesis. 1985;6:1167–1172. doi: 10.1093/carcin/6.8.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yan T, Oberley L W, Zhong W, St. Clair D K. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2864–2871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Church S L, Grant J W, Ridnour L A, Oberley L W, Swanson P E, Meltzer P S, Trent J M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3113–3117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.3113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fernandez-Pol J A, Hamilton P D, Klos D J. Cancer Res. 1982;42:609–617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li N, Oberley T D, Oberley L W, Zhong W. J Cell Physiol. 2000;175:359–369. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199806)175:3<359::AID-JCP14>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Haan J B, Cristiano F, Iannello R, Bladier C, Kelner M J, Kola I. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:283–292. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.2.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wartenberg M, Diedershagen H, Hescheler J, Sauer H. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:27759–27767. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.39.27759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bae G-U, Seo D-W, Kwon H-K, Lee H Y, Hong S, Lee Z-W, Ha K-S, Lee H-W, Han J-W. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:32596–32602. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.46.32596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Natarajan V, Taher M M, Roehm B, Parinandi N L, Schmid H H O, Kiss Z, Garcia J G N. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:930–937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allen R G, Tresini M. Free Radical Biol Med. 2000;28:463–499. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00242-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simon A, Rai U, Fanburg B, Cochran B. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:C1640–C1652. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.6.C1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Finkel T. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:248–253. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80147-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abe J, Okuda M, Huang Q, Yoshiqumi M, Berk B C. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:1739–1748. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.3.1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Min D S, Kim E-G, Exton J H. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:29986–29994. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee S-R, Kwon K-S, Kim S-R, Rhee S G. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:15366–15372. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barrett W C, DeGnore J P, Keng Y-F, Zhang Z-Y, Yim M B, Chock P B. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:34543–34546. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.34543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmidt K, Amstad K, Cerutti P, Baeuerle P. Chem Biol. 1995;2:13–22. doi: 10.1016/1074-5521(95)90076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wenk J, Brenneisen P, Wlaschek M, Poswig A, Brivba K, Oberley T D, Scharffetter-Kochanek K. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:25869–25876. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hainaut P, Milner J. Cancer Res. 1993;53:4469–4473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Demple B. Gene. 1996;179:53–57. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00329-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Storz G, Imlay J A. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2:188–194. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(99)80033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boehm T, Folkman J, Browder T, O'Reilly M. Nature (London) 1997;390:404–407. doi: 10.1038/37126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Godon C, Lagniel G, Lee J, Buhler J-M, Kieffer S, Perrot M, Boucherie H, Toledano M, Labarre J. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:22480–22489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.35.22480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morgan R W, Christman M F, Jacobson F S, Storz G, Ames B N. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:8059–8063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.21.8059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]