Abstract

Introduction

Chronic constipation is significantly more prevalent in women than men in Singapore. We carried out a survey to study patient demographics, symptom prevalence, healthcare-seeking behavior, and patient satisfaction with available treatment options in women with chronic constipation.

Methods

Responses were collected predominantly via a web-based survey from a panel representative of Singapore’s women population. Eligibility was established using a nine-question screener.

Results

A total of 1006 invited females took part in an online screener survey, of which 911 respondents did not meet the eligibility requirements for the chronic constipation survey. Of the total panelists consenting to participate (via both online and face-to-face interviews), 100 women met eligibility requirements and took the 22-question survey. Eligible respondents were skewed to younger patients but well mixed in terms of marital status. The majority of them were not keen on doing exercise and were working women, especially white collar females. The majority complained of straining and hard stools as the most common constipation symptoms (88% and 80% respectively) and rated constipation symptoms as severe or moderate. On average, respondents experienced constipation symptoms for 6 to 7 months in the last year. In more than two-thirds of respondents, constipation symptoms were frequent (at least 1 in 3 times). Most of the patients had attempted to treat constipation themselves and 80% had tried laxatives before visiting the doctor. Satisfaction with fiber supplements and laxatives was average and many of the users were not satisfied with their effect. Ineffectiveness and prolonged time taken for the treatment to take effect were the most common reasons for dissatisfaction. Nearly all respondents (97%) were interested in considering alternative prescriptive medication that is proven more effective.

Conclusion

Chronic constipation symptoms in women are often severe and bothersome, and many patients are dissatisfied with available treatment options primarily because of lack of efficacy.

Keywords: chronic constipation, demographics, health-care, laxatives

Introduction

The word constipation often has a different meaning for physicians and patients. Although physicians generally equate constipation with reduced stool frequency, patients use this term to describe a variety of problems associated with their bowel habits.1 The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) Chronic Constipation Task Force defines constipation as unsatisfactory defecation characterized by infrequent stools, difficult stool passage, or both. Constipation is termed chronic when symptoms have been present for at least 3 months.2 When an endocrine, metabolic, neurologic, structural, or iatrogenic explanation can be identified, constipation is said to be secondary. In the absence of an organic cause, constipation is said to be primary, functional or idiopathic. 3 Chronic functional constipation has been defined as a symptom-based disorder by an international committee that had its meeting in Rome. However, observational studies indicate that most patients who report constipation symptoms do not fulfill Rome criteria for chronic functional constipation.2

Heaton et al have found that a regular once-daily bowel habit is actually enjoyed by less than half the population and in this aspect of human physiology, younger women are especially disadvantaged. Women’s stool types incline towards the constipated end on the Bristol stool types scale (hard and lumpy stools) in comparison to men of the same age, with higher prevalence.4 There are several reports of lower fecal output or slower intestinal transit or both in healthy women compared with men.5–7 Other investigators have focused on the role of female sex hormones, as women often report changes in bowel function during different stages of their menstrual cycle. Progesterone is thought to decrease the rate of small bowel and colonic transit time, contributing to constipation during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle.8 Damage to the pelvic floor muscles and their innervations, which may occur during childbirth or during gynecological surgery, may also contribute to constipation in women.9

Constipation is often perceived to be a benign, easily treated condition with short-term treatment being relatively straightforward; however, poorly managed chronic constipation is associated with a variety of complications ranging from mild to severe eg, fecal incontinence, hemorrhoids, anal fissure, organ prolapse, fecal impaction and bowel obstruction, bowel perforation and stercoral peritonitis.10,11 One of these, fecal impaction, has been identified in 40% of older adults hospitalized in the UK.12,13 This complication can lead to urinary and fecal incontinence and in extreme yet rare instances, fecal impaction may result in other disorders including stercoral ulceration or bowel perforation.14 Left untreated, these latter two complications may worsen in severity and become life threatening. Unfortunately, many of the chronic constipated patients are young adults in the most productive years of their life. In Singapore, around 8.3% of constipated patients are so distressed by inadequately treated symptoms that they even accede to surgical treatments like colectomy.15

Due to the aforementioned factors, constipation should be considered a major public health issue and knowledge of its epidemiology is highly relevant to primary care providers, gastroenterologists, and health care policy makers. In Singapore, women were found to have a far higher prevalence of chronic constipation than men (11.3% versus 3.6%).16 In light of this higher prevalence of chronic constipation in Singaporean women, systematic evaluation of their characteristics, magnitude of the problem and treatment-seeking behavior would be useful to clinicians. Therefore, the purpose of our survey was to study the demographics, risk factors, patient symptoms, healthcare-seeking behavior, and patient satisfaction with current treatment options in women with chronic constipation.

Methods

Study subjects

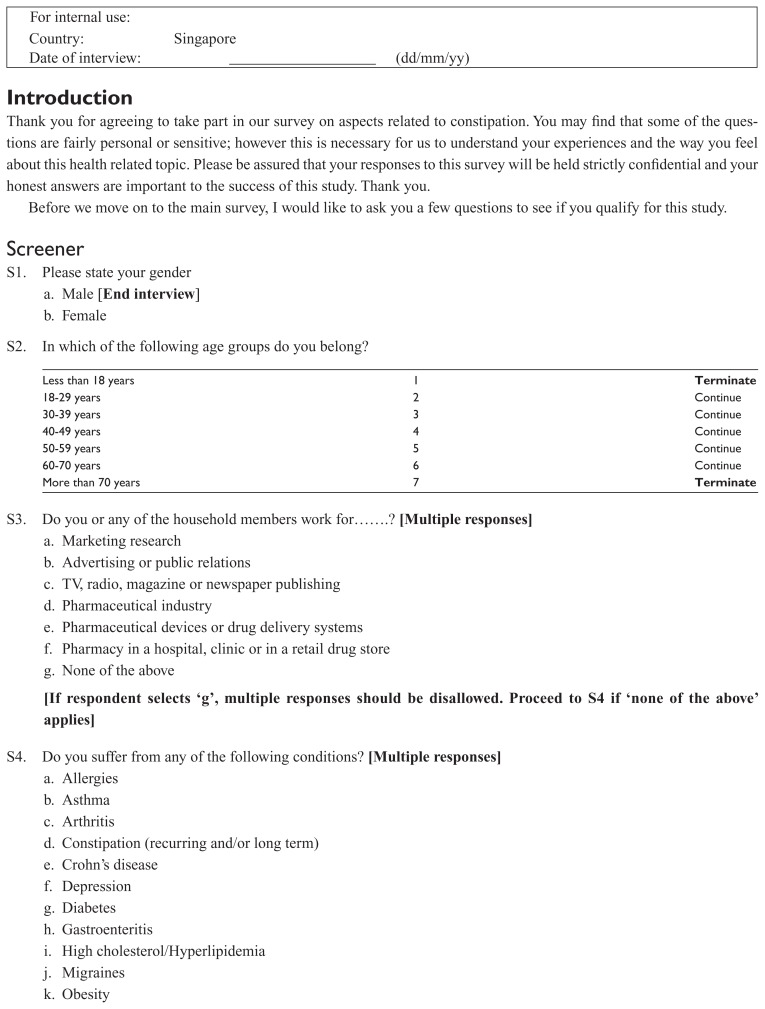

Responses were predominantly collected via a web-based (online) survey from members of a consumer panel. Within the panel, we took steps to ensure that we collected a randomized sample of the panel, using demographics of the intended target population from their previous registration information to draw the sample frame to use for survey invitations. On the back end we applied weighting techniques to ensure that the total universe of qualified and nonqualified was weighted to match the targeted population. We sent out around 5000 emails to women aged between 18–70 years old inviting them to take part in an online survey. The invitation email did not contain any information about the project. To ensure that the panel was representative of the Singapore population, participants were also recruited through face-to-face interviews to reach out to older respondents aged 60 years old or above (who were not as easily found online). Fieldwork was conducted in March and April 2011. Survey responses were confidential, and participants’ identity was never revealed. Participants had the option to leave the panel at any time. Surveys were conducted according to the globally accepted standards of good clinical practice (as defined in the ICH E6 Guideline for Good Clinical Practice, May 1, 1996) in agreement with the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki and in accordance with the local regulations.

Eligibility

Everyone who agreed to participate in the survey was asked to complete an online self-administered nine-question screener to evaluate whether they met entry criteria of having chronic constipation. Constipation is a subjective term used to describe difficulty in defecation, either because of the infrequent passage of small hard stools, or straining at defecation, or both.17 In our survey, participants who strained at the stools or passed hard stools >25% of the time or passed < 3 stools per week for the past 3 months or more were defined as having chronic constipation. The definition of chronic constipation in our survey was also based on the criteria followed in a previous local study that gathered data on the epidemiology of bowel frequency and functional bowel disorders in Singapore.16 Recruits were only eligible to participate in this survey if they were females and 18 years of age or older and less than 70 years of age.

Exclusion criteria

Participants who had not taken any kind of treatment to relieve their constipation in the last 12 months were excluded. Participants were also not eligible to participate in the survey if they or any of their household members worked for marketing research, advertising or public relations, TV, radio, magazine or newspaper publishing, pharmaceutical industry, pharmaceutical devices or drug delivery systems or a pharmacy in a hospital or clinic or in a retail drug store.

Survey administration

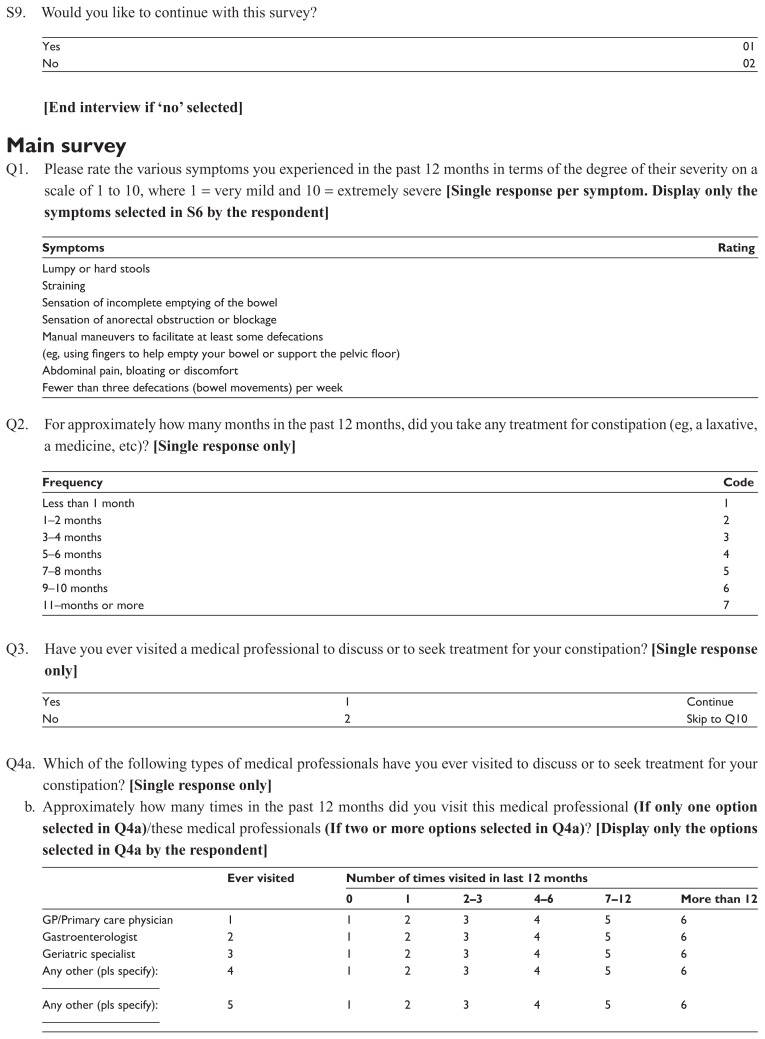

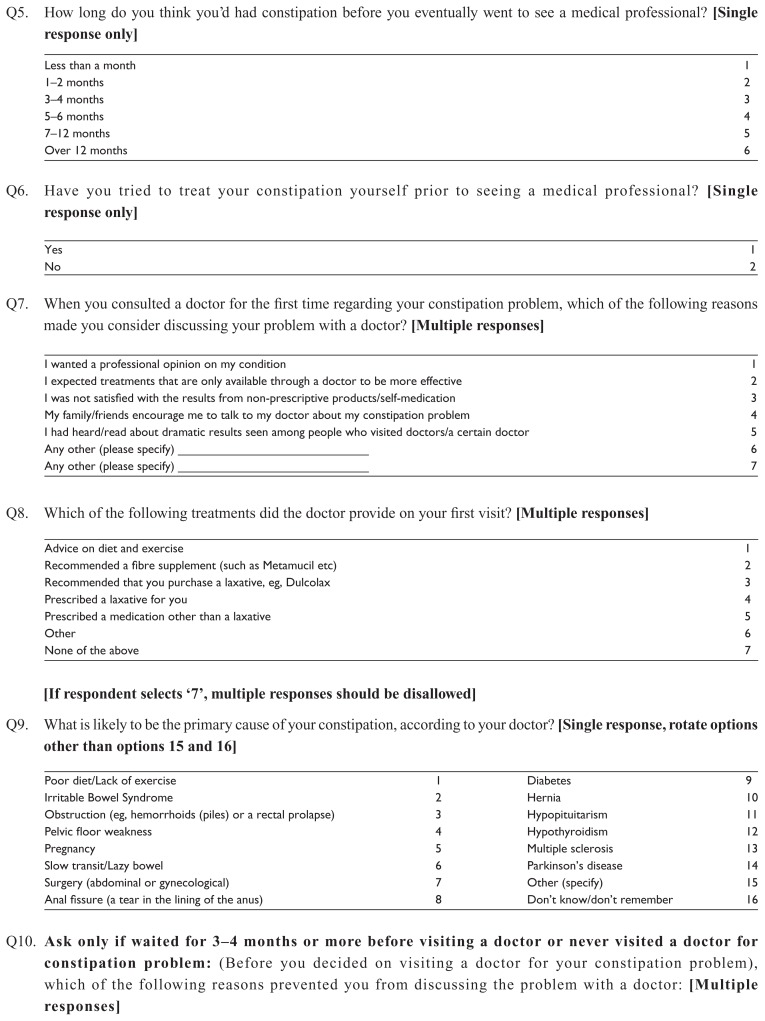

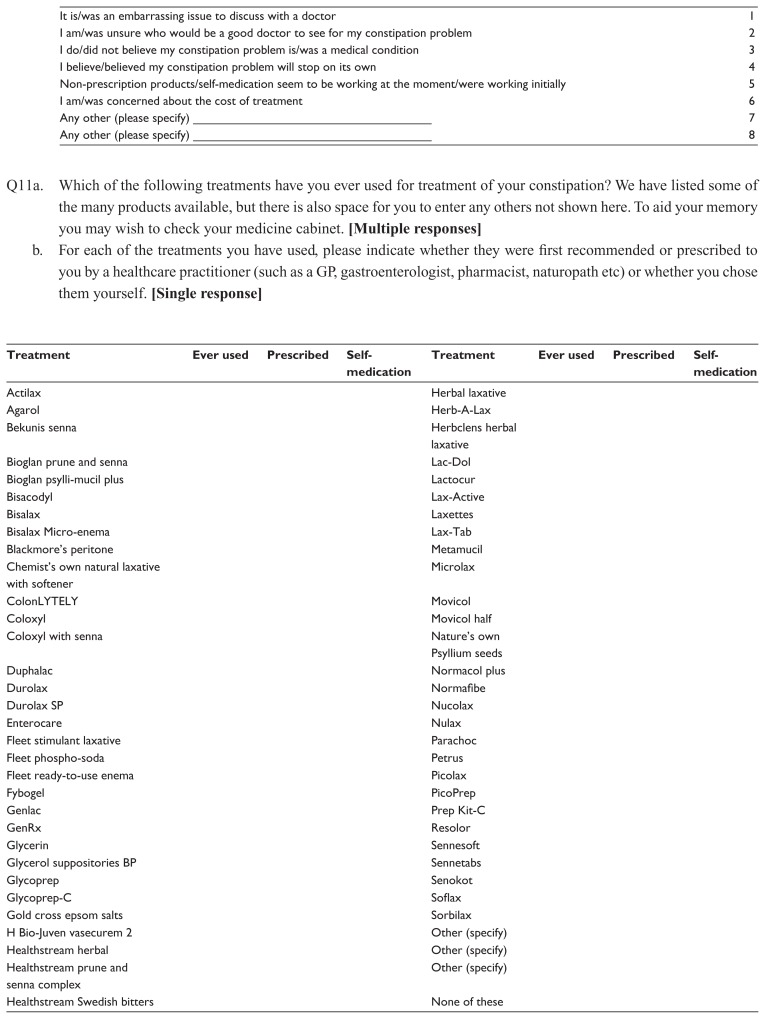

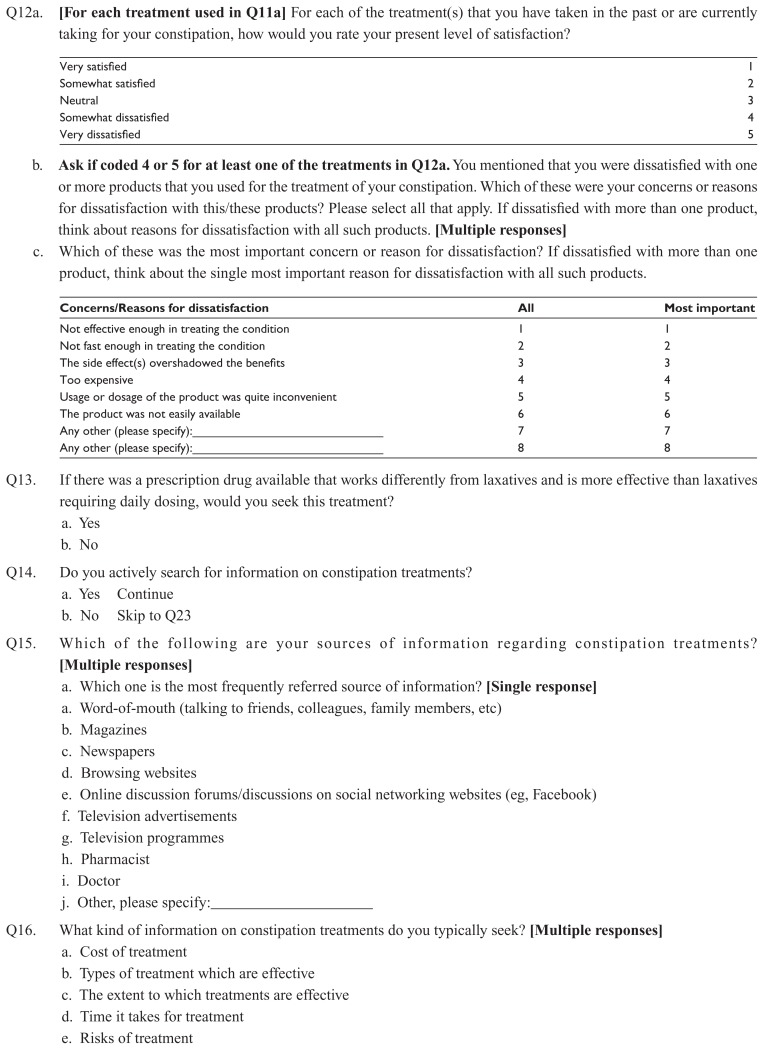

Panelists meeting the entry criteria completed an online, self-administered, 22-question survey including 6 questions on patient demographics. The length of the questionnaire was approximately 20 minutes and it was administered in English. Participants were directed to read and understand an informed consent document, after which they were given the option of continuing with the survey. Panelists were also advised that their participation was voluntary and that they had the option of not answering specific questions. The questionnaire allowed us to estimate the symptom prevalence of chronic constipation, the frequency of healthcare seeking for constipation and the utilization of fiber supplements/laxatives. In addition, sociodemographic and lifestyle variables were included. To identify the frequency and severity of their constipation symptoms, symptoms were rated as severe if the participants gave a top 3 box rating on a scale of 1–10 and mild if they gave a bottom 3 box rating on a scale of 1–10. The study questionnaire is reproduced as the Appendix.

Results

A total of 1072 respondents (men and women) took part in this online survey. As we sent survey invitations only to females, all participants were females (n = 1006). Of these, 911 respondents did not meet the eligibility requirements for the 22-question chronic constipation survey and were excluded. The reasons for their exclusion were “age not between 18–70 years” (n = 32), “worked for marketing research or other confounding places” (n = 182), “did not suffer from recurring and/or long term constipation” (n = 307), “had not taken any kind of treatment to relieve their constipation in the last 12 months” (n = 173), “did not qualify as having chronic constipation criteria” (n = 185), “left the screener survey midway” (n = 30) and “did not want to continue with the main survey” (n = 2). After this preliminarily screening of the panelists, 95 respondents were found eligible for the 22-question main survey. An additional five participants, aged 60 or above, recruited via face-to-face interview were found to be eligible for the main survey. The total number of respondents with chronic constipation eligible for the main survey was 100.

Demographics of eligible respondents

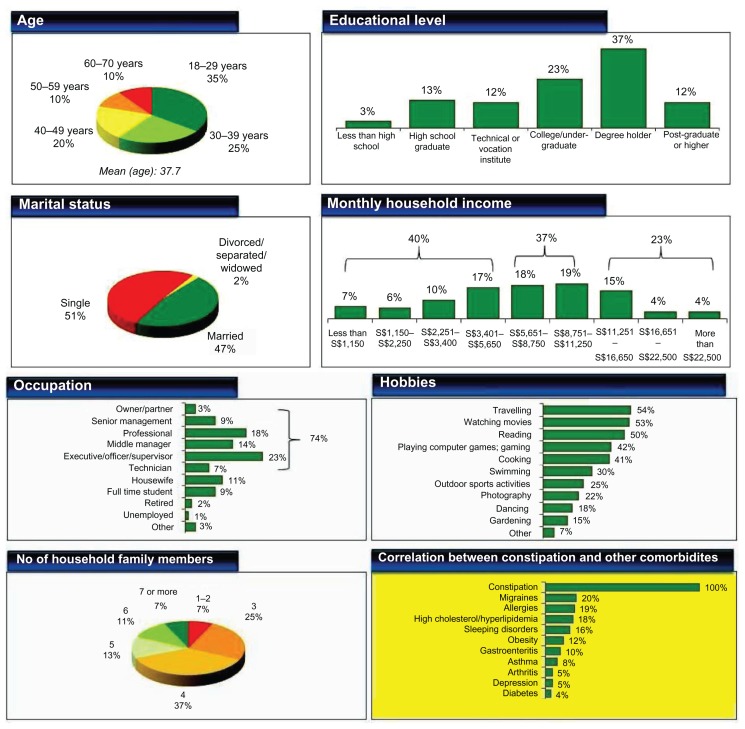

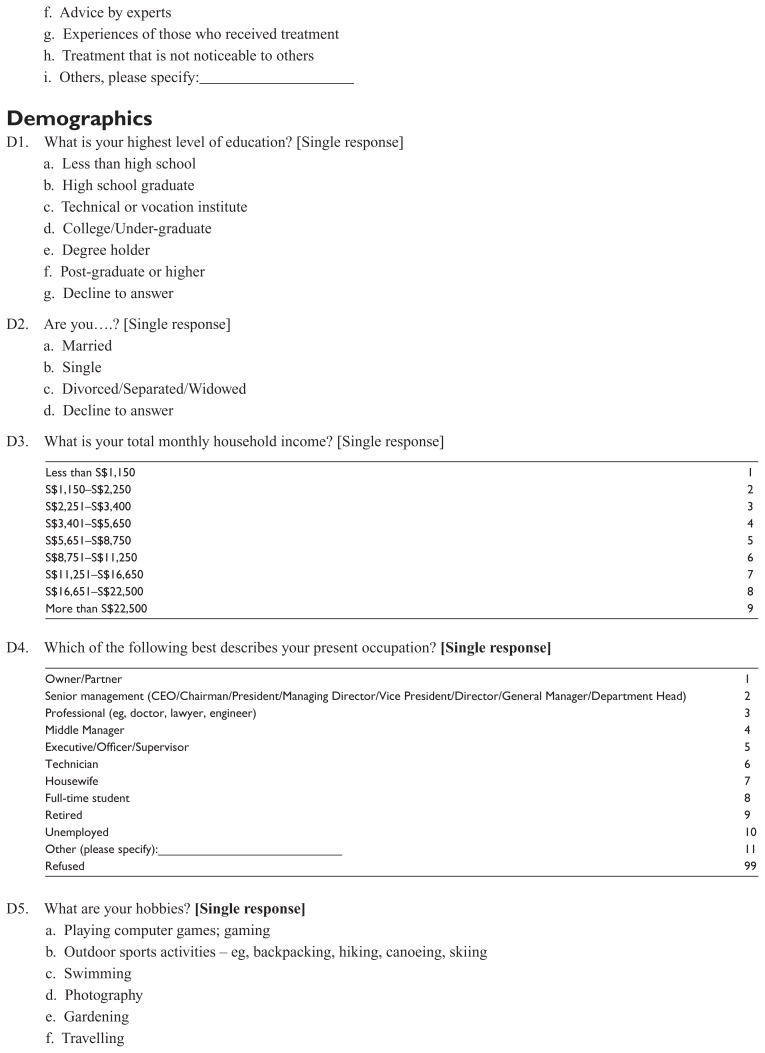

Eligible respondents for this survey were skewed to younger patients, aged 18–39 but well mixed in terms of marital status. The age distribution of this sample consisted of 60% aged 18–39 years, 30% aged 40–59 years and 10% aged 60–70 years. Half of the respondents held degrees or higher education qualifications and slightly more than half had monthly household incomes of more than SGD$5600. The majority of the respondents were working women; most of them (64%) were professional or at management or supervisory level. Less than one-third of the respondents liked swimming or doing outdoor activities in their free time or listed them as their hobbies. No obvious correlations between constipation and other illnesses were observed (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Eligible respondent demographics (n = 100).

Constipation symptoms

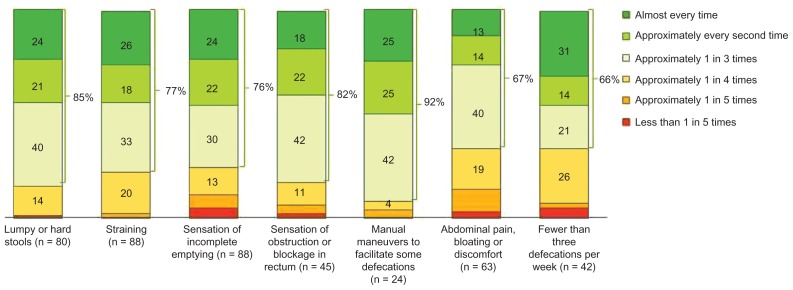

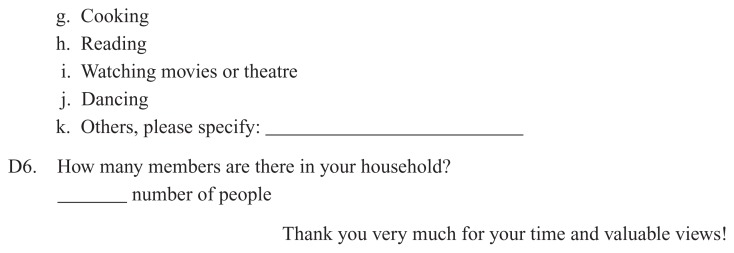

Overall, straining and lumpy or hard stools were the two most common constipation symptoms experienced by 88 and 80 percent of all eligible respondents respectively. Sensations of incomplete emptying and abdominal pain, bloating or discomfort were experienced by 60% of all eligible respondents. Sensations of obstruction or blockage in the rectum while passing stool, fewer than three bowel movements per week and manual maneuvers to facilitate at least some defecations were experienced by only 45, 42, and 24 percent of eligible respondents respectively. Straining was a more predominant symptom among the younger age groups while lumpy or hard stools were more prevalent among the middle to older age groups (Table 1). The various constipation symptoms were rated as severe or moderate by the majority of the patients (Table 2). More than one-third of the respondents rated the constipation symptoms as severe (they gave a top 3 box rating on a scale of 1–10). On average, respondents experienced constipation symptoms for 6 to 7 months in the last year. The average frequency for various constipation symptoms was approximately 1 in 3 times or more often in more than two-thirds of respondents (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Age-wise distribution of various constipation symptoms in the eligible respondents

| Constipation symptom | Overall (%) (n = 100) |

18–29 years (%) (n = 35) |

30–39 years (%) (n = 25) |

40–49 years (%) (n = 20) |

50–59 years (%) (n = 10) |

60–70 years (%) (n = 10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Straining | 88 | 97 | 88 | 95 | 60 | 70 |

| HS | 80 | 69 | 72 | 100 | 100 | 80 |

| SIE | 63 | 71 | 40 | 70 | 70 | 70 |

| AP/B | 63 | 66 | 72 | 60 | 60 | 40 |

| SOB | 45 | 43 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 40 |

| <3/week | 42 | 49 | 36 | 45 | 10 | 60 |

| MM | 24 | 23 | 28 | 25 | 40 | – |

Abbreviations: HS, hard stools; SIE, sensation of incomplete emptying; AP/B, abdominal pain/bloating/discomfort; SOB, sensation of obstruction/blockage in rectum while passing stool; <3/week, <3 defecations/week; MM, manual maneuvers to facilitate at least some defecations.

Table 2.

Severity rating* for the various constipation symptoms by the eligible respondents (n = 100)

| Constipation symptom | Straining (n = 88) |

HS (n = 80) |

SIE (n = 63) |

AP/B (n = 63) |

SOB (n = 45) |

<3/week (n = 42) |

MM (n = 24) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severe (%) | 39 | 40 | 38 | 44 | 42 | 52 | 42 |

| Moderate (%) | 53 | 50 | 51 | 46 | 49 | 36 | 50 |

| Mild (%) | 8 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 12 | 8 |

Note:

Symptoms were rated as severe if the participants gave a top 3 box rating on a scale of 1–10 and mild if they gave a bottom 3 box rating on a scale of 1–10.

Abbreviations: HS, hard stools; SIE, sensation of incomplete emptying; AP/B, abdominal pain/bloating/discomfort; SOB, sensation of obstruction/blockage in rectum while passing stool; <3/week, <3 defecations/week; MM, manual maneuvers to facilitate at least some defecations.

Figure 2.

Frequency of constipation symptoms in eligible respondents (n = 100) in the past 12 months.

Notes: Question S8 from the Appendix: During the months when you experienced these symptoms in the past 12 months, roughly for what proportion of the times you went to the toilet (had a bowel motion) would each of these symptoms have been present? If frequency varied across the months that you experienced this symptom, please mention the approximate average frequency across the various months that you experienced it. [Single response per symptom.]

Treatment-seeking behavior

Most of the respondents (84%) took some form of treatment for constipation for at least 1–2 months in the past 1 year. The majority of them (42%) took treatment for 3–6 months, 25% took treatment for >6 months and 33% took treatment for <2 months. A total of 70% of the respondents had visited a medical professional to discuss and seek treatment for constipation. There was a similar pattern observed across the age groups. Monthly income of the individual did not seem to play a role in whether a medical professional was consulted for treatment. Almost 94% of the patients had attempted to treat constipation themselves prior to visiting a doctor. Nearly 80% of the patients had tried laxatives before visiting the doctor. This figure was higher among the older age groups. A total of 60% of respondents went to see a doctor within 4 months of their constipation problems starting, whereas 21% had waited for more than half a year. The average duration of constipation before seeing a doctor was 4.7 months. Respondents in their 30s tended to seek treatment from medical professionals earlier than other age groups. No relationship was observed between educational status and time to seek treatment.

The majority of the respondents who had visited a doctor did so because they felt the doctor could offer a professional opinion on their condition and believed the treatments that are only available through a doctor would be more effective. About half of respondents were triggered by the unsatisfactory results of nonprescription products and self-medication or encouraged by family or friends. The “stigma” attached with discussing embarrassing ailments such as constipation, the belief that “constipation is not a medical condition” and “it will stop on its own” were the main factors for not seeking treatment from doctors early enough if at all. The cost of treatment was the least important reason for not visiting a doctor. General practitioners and primary care physicians were consulted the most for constipation treatment (77%). Around 40% had also visited gastroenterologists while the incidence of seeing a geriatric specialist was rather low. No respondent mentioned any other types of doctor they had visited for constipation problems. Poor diet/lack of exercise was quoted by the doctor as the primary cause of constipation (40%). Other common causes quoted included irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and slow transit (10% each).

Treatment satisfaction

Nearly two-thirds of respondents were prescribed fiber supplements and given advice on diet and exercise to treat constipation during their first visit. Only about half were prescribed laxatives, and this treatment was less popular among young patients aged 18–29 years old. In spite of the higher usage, satisfaction with fiber supplements was average as fewer than half of the users were satisfied with their effect. On the other hand, users of laxatives shared a higher level of satisfaction (65%). “Ineffectiveness” and “long time taken for the treatment to take effect” were the most common reasons for treatment dissatisfaction (91% and 73% respectively). Other reasons for treatment dissatisfaction were, “side effect(s) overshadowed the benefits” (36%), “usage or dosage of the product was quite inconvenient” (36%) and “the product was not easily available” (18%). Nearly all respondents (97%) were interested in considering alternative prescriptive medication that is proven more effective.

Searching for information regarding constipation treatment

Over 60% of the respondents had searched for information regarding treatment of constipation. Respondents with better education were more proactive in their information search. Word of mouth, browsing websites, and discussions on social networking websites were the most frequently cited sources of information. Nearly everyone who searched for information on constipation looked for effective treatments for constipation. Other popular topics included effectiveness, cost, duration and risks of the treatments, experts’ advice, and experience sharing. While the older age groups tended to research more on the effectiveness of treatment, younger age groups seemed more interested in the cost of treatment.

Discussion

Constipation is a common problem worldwide and affects between 2% and 28% of the general population.18 As only a minority of patients suffering from constipation seek health care, its exact prevalence is difficult to ascertain. There has been no correlation between the sample size of study participants and prevalence rates.19 The varied prevalence of chronic constipation also arises from different definitions of constipation used in different studies. There is no formal clinical definition, and clinicians, patients, and diagnostic criteria define constipation differently. Unlike physicians, patients are more concerned with ease of passage of stool and consistency rather than stool frequency.20 This is consistent with the findings of our survey as the majority of the women complained of “straining and lumpy” or “hard stools” as the most common constipation symptoms while “fewer than three bowel movements per week” were experienced by less than half of the eligible respondents. In addition, most of the eligible respondents experienced constipation symptoms for more than 6 months with a middle to high degree of severity. The frequency for the symptoms experienced in most respondents was at least one in three times (Figure 2) which is significantly higher than the minimum frequency in ROME III criteria for diagnosis of chronic constipation (at least one in four times).21

Multiple associated factors for constipation in the general population have been identified eg, female gender, increasing age, socioeconomic status and educational level.19 There is also a trend towards increased prevalence of constipation in individuals with immobility or less self-reported physical activity.19,22 Various other risk factors found to be associated with constipation include low consumption of fiber, fruit and vegetables,23 experiencing anxiety and depression.24,25 Interestingly, the majority of the eligible respondents with chronic constipation in our survey were not keen on doing exercise or interested in sports.

Bytzer et al found a trend for higher prevalence of constipation in individuals of lower social classes in Australian adults,26 however, many of the Singaporean women with chronic constipation in our survey were white collar workers. A possible explanation for these findings might relate to the high level of anxiety in these women, as female sex and anxiety have been found to be two independent factors in predicting the perception of constipation. It has been reported that patients with normal transit severe constipation suffer from increased psychological distress27 and constipation associated with anxiety is prevalent in the Chinese population.25 Anxiety is known to be associated with alterations in central autonomic activity, and this may manifest as a functional gut disturbance. Impaired psychosocial function has been found in women with constipation and is associated with altered rectal mucosal blood flow, a measure of extrinsic gut innervation.28 Higher anxiety levels in females associated with more frequent perception of constipation symptoms also possibly explains the predominance of female gender in idiopathic constipation.25

It has been found that between 22.3% and 48.3% of the population with constipation seeks medical health care. Despite the fact that constipation affects daily quality of life, it has been hypothesized that many constipated people believe that they can manage the problem themselves.19 In our survey 94% of the patients had attempted to treat constipation themselves prior to visiting a doctor. Nearly 80% of the patients had tried laxatives before visiting the doctor and the average duration of constipation before seeing a doctor was 4.7 months. Income did not seem to play a role in whether a medical professional was consulted for treatment.

Traditional therapies for chronic constipation include dietary and lifestyle interventions, fiber supplements, stool softeners, osmotic agents and stimulant laxatives. Despite their enormous use, there are relatively few well-conducted clinical trials of these agents in the literature. In the position statement and systematic review of the traditional therapies for constipation, only lactulose and polyethylene glycol received “grade A” recommendation ( recommendation supported by 2 or more level I trials without conflicting evidence from other level I trials).2 Also side effects such as nausea, bloating, abdominal cramping, flatulence, diarrhea, and electrolyte disturbances can limit the use of traditional therapies for constipation.2 In a similar internet-based survey of US patients with constipation, 47% of respondents were not completely satisfied with their treatment for constipation.29 In our survey satisfaction with fiber supplements was average as fewer than half of the users were satisfied with their effect. Even for laxatives, only 65% of patients were satisfied with the treatment. For most, a lack of efficacy was the leading reason for dissatisfaction. Nearly all respondents (97%) were interested in considering alternative prescriptive medication that is proven more effective. This survey confirmed the fact that many people with chronic constipation are disappointed with the efficacy of traditional treatment approaches.

Although this chronic constipation survey in Singaporean women provides physicians an estimate of the magnitude of the problem, when interpreting the findings of this survey one should take into consideration various limitations and shortcomings. First, the use of questionnaires depends on the ability of the patient to recall symptoms, whereas prospective studies with the administration of diary cards are certainly more credible. In addition, as many of the eligible respondents had used more than one class of laxatives we could not analyze the data for patient satisfaction for different groups of laxatives, for example, bulking agents, stimulants, osmotic agents, and stool softeners.

Conclusion

Most women with chronic constipation in Singapore experience constipation symptoms for more than 6 months, with frequent recurrence and a middle to high degree of severity. Stool frequency is not as bothersome as the need to strain and the passage of hard stools. The majority of the women have taken some form of laxative by the time they consult about constipation. However many of these subjects remain unsatisfied with the effect of these agents. The experiences of patients thus seem to corroborate the relative paucity of highly effective therapies for chronic constipation.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the management and staff of Harris Interactive Inc for their extraordinary efforts in screening the respondents and carrying out interviews with the eligible respondents.

In addition, we wish to acknowledge with deep appreciation the generous contribution by Jennifer Colamonico, Senior Vice President, Healthcare Research, Harris Interactive Inc, New York.

Appendix: Chronic constipation study questionnaire

Footnotes

Disclosure

Dr Kok Ann Gwee has received research grants from Janssen and Abbott. Dr Sajita Setia is an employee of Janssen, a division of Johnson and Johnson Pte Ltd. This study was funded in full by Janssen.

References

- 1.Herz MJ, Kahan E, Zalevski S, Aframian R, Kuznitz D, Reichman S. Constipation: a different entity for patients and doctors. Fam Pract. 1996;13(2):156–159. doi: 10.1093/fampra/13.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.An evidence-based approach to the management of chronic constipation in North America. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(Suppl 1):S1–S4. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.50613_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mertz H, Naliboff B, Mayer EA. Symptoms and physiology in severe chronic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(1):131–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heaton KW, Radvan J, Cripps H, Mountford RA, Braddon FE, Hughes AO. Defecation frequency and timing, and stool form in the general population: a prospective study. Gut. 1992;33(6):818–824. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.6.818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stephen AM, Wiggins HS, Englyst HN, Cole TJ, Wayman BJ, Cummings JH. The effect of age, sex and level of intake of dietary fibre from wheat on large-bowel function in thirty healthy subjects. Br J Nutr. 1986;56(2):349–361. doi: 10.1079/bjn19860116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies GJ, Crowder M, Reid B, Dickerson JW. Bowel function measurements of individuals with different eating patterns. Gut. 1986;27(2):164–169. doi: 10.1136/gut.27.2.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sandler RS, Jordan MC, Shelton BJ. Demographic and dietary determinants of constipation in the US population. Am J Public Health. 1990;80(2):185–189. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.2.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jung HK, Kim DY, Moon IH. Effects of gender and menstrual cycle on colonic transit time in healthy subjects. Korean J Intern Med. 2003;18(3):181–186. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2003.18.3.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiarelli P, Brown W, McElduff P. Constipation in Australian women: prevalence and associated factors. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2000;11(2):71–78. doi: 10.1007/s001920050073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dennison C, Prasad M, Lloyd A, Bhattacharyya SK, Dhawan R, Coyne K. The health-related quality of life and economic burden of constipation. Pharmacoeconomics. 2005;23(5):461–476. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200523050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leung L, Riutta T, Kotecha J, Rosser W. Chronic constipation: an evidence-based review. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24(4):436–451. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2011.04.100272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wrenn K. Fecal impaction. N Engl J Med. 1989;321(10):658–662. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198909073211007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Read NW, Celik AF, Katsinelos P. Constipation and incontinence in the elderly. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;20(1):61–70. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199501000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kallman H. Constipation in the elderly. Am Fam Physician. 1983;27(1):179–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ho YH, Goh HS. The investigation of chronic constipation for surgical management. Singapore Med J. 1996;37(3):291–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen LY, Ho KY, Phua KH. Normal bowel habits and prevalence of functional bowel disorders in Singaporean adults – findings from a community based study in Bishan. Community Medicine GI Study Group. Singapore Med J. 2000;41(6):255–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moore-Gillon V. Constipation: what does the patient mean? J R Soc Med. 1984;77(2):108–110. doi: 10.1177/014107688407700207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCrea GL, Miaskowski C, Stotts NA, Macera L, Varma MG. A review of the literature on gender and age differences in the prevalence and characteristics of constipation in North America. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37(4):737–745. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mugie SM, Benninga MA, Di Lorenzo C. Epidemiology of constipation in children and adults: a systematic review. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;25(1):3–18. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanchez MI, Bercik P. Epidemiology and burden of chronic constipation. Can J Gastroenterol. 2011;25(Suppl B):11B–15B. doi: 10.1155/2011/974573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drost J, Harris LA. Diagnosis and management of chronic constipation. JAAPA. 2006;19(11):24–29. doi: 10.1097/01720610-200611000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wald A, Scarpignato C, Mueller-Lissner S, et al. A multinational survey of prevalence and patterns of laxative use among adults with self-defined constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28(7):917–930. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dukas L, Willett WC, Giovannucci EL. Association between physical activity, fiber intake, and other lifestyle variables and constipation in a study of women. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(8):1790–1796. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haug TT, Mykletun A, Dahl AA. Are anxiety and depression related to gastrointestinal symptoms in the general population? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37(3):294–298. doi: 10.1080/003655202317284192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng C, Chan AO, Hui WM, Lam SK. Coping strategies, illness perception, anxiety and depression of patients with idiopathic constipation: a population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18(3):319–326. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bytzer P, Howell S, Leemon M, Young LJ, Jones MP, Talley NJ. Low socioeconomic class is a risk factor for upper and lower gastrointestinal symptoms: a population based study in 15,000 Australian adults. Gut. 2001;49(1):66–72. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.1.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grotz RL, Pemberton JH, Talley NJ, Rath DM, Zinsmeister AR. Discriminant value of psychological distress, symptom profiles, and segmental colonic dysfunction in outpatients with severe idiopathic constipation. Gut. 1994;35(6):798–802. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.6.798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Emmanuel AV, Mason HJ, Kamm MA. Relationship between psychological state and level of activity of extrinsic gut innervation in patients with a functional gut disorder. Gut. 2001;49(2):209–213. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.2.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johanson JF, Kralstein J. Chronic constipation: a survey of the patient perspective. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25(5):599–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]