Abstract

Objective. To assess the effect of sulfotanshinone sodium injection for unstable angina. Methods. We searched for published and unpublished studies up to June 2011. We included randomized controlled trials that confoundedly addressed the effect of sulfotanshinone sodium injection in the treatment of unstable angina. Results. Twenty-five studies involving 2,377 people were included. There was no evidence that sulfotanshinone sodium alone had better or worse effects to routine western medicine treatments in improving clinical symptoms (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.11) and ECG (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.09). However, there was evidence that sulfotanshinone sodium combined with western medications was a better treatment option than western medications alone in improving clinical symptoms (RR 1.28, 95% CI 1.23 to 1.3), ECG (RR 1.26, 95% CI 1.18 to 1.35), C-reaction protein (mean difference 2.10, 95% CI 1.63 to 2.58), and IL-6 (mean difference −3.85, 95% CI −4.10 to −3.60). There was no difference between sulfotanshinone sodium plus western medications and western medications alone affecting mortality (RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.02 to 12.13). Conclusion. Compared with western medications alone, sulfotanshinone sodium combined with western medications may provide more benefits for patients with unstable angina. Further large-scale high-quality trials are warranted.

1. Introduction

Coronary artery disease is the leading cause of death in the United States [1]. Early hospital care for unstable angina includes anti-ischemic therapies, antiplatelet therapies, and anticoagulant/antithrombotic therapies and may also consider an early invasive strategy [2]. Thrombolytic agents are usually more frequently used for more severe conditions [3–5].

Danshen, also known as Salvia miltiorrhiza Bge, is a hemorheologic agent that may have protective effect in patients with unstable angina [6] and has been used for cardiovascular disorders for hundreds of years in China and now is widely used in other countries as well.

Danshen consists of a mixture of compounds, among which Tanshinone IIA (TIIA) represents the most biologically active ingredient [7]. TIIA, also known as Danshen ketone, Tanshinon II, Tanshinone B, is a diterpenoid naphthoquinone extracted and isolatedderivative from Danshen. Animal and cellular studies have shown various potential benefits of the agent, including (1) neuroprotective effect in cerebral ischemia and reperfusion [8], (2) antioxidant potential to prevent oxidation of low-density lipoproteins [9], (3) ability of rescuing PC-12 cells from hypoxia [10], (4) reducing cellular damage by free radicals [11], (5) protecting mitochondrial membrane from ischemia-reperfusion injury and lipid peroxidation [12], (6) decreasing PHB expression in oxidative stress-injured myocardial cells hence protecting the myocardial cells [13], (7) protecting cardiomyocytes against oxidative stress-mediated apoptosis [14], and (8) cardioprotective in the context of diabetic cardiomyopathy through kinin B2 receptor-Akt-GSK-3β-dependent pathway [15]. Human studies also have demonstrated cardioprotective effects of TIIA, including reduction of myocardial infarct size and decrease of myocardial consumption of oxygen [16].

Until now, the clinically available TIIA agent, which is approved by State Food and Drug Administration of China, only includes sulfotanshinone sodium (SS) injection (i.e., sodium tanshinone IIA sulfonate injection) manufactured by two companies. TIIA is extracted from the raw herb Danshen and then chemically derivatized into water-soluble SS for the preparation of injection. Upon the administration of SS injection, SS transforms back into the bioactive ingredient TIIA in vivo [17]. The dosage for administration of SS injection is 40–80 mg per day. SS injection is given diluted at the point of treatment in 20 mL 25% glucose injection for intramuscular administration or in 250–500 mL 5% glucose injection for intravenous administration. It is widely used in the Chinese hospitals for unstable angina [18].

However, the effects of SS injection on unstable angina have not been well established. In this study, we evaluated the effect of SS through a rigorous systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials.

2. Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

We included randomized controlled trials that compared SS with placebo or active agents in patients with unstable angina defined as new onset (≤2 months) exertional angina of at least Canadian Cardiovascular Society Classification (CCSC) class III in severity, significant recent increase in frequency and severity of angina, or angina at rest.

The eligible comparisons include

SS injection versus any current western medications,

SS injection plus any current western medications for unstable angina versus western medications alone,

SS injection versus placebo.

Our prespecified primary outcome is all-cause mortality, and secondary outcomes include resolution of angina, ECG improvement, inflammatory factors (such as C-reaction protein and IL-6), and adverse events. The improvement of clinical symptoms is measured as the reduction in chest pain and shortness of breath or the frequency, severity, and length of acute angina attacks. “Very effective” includes that there is no angina attack, chest pain disappears, ST segment depression is back to normal, or the depression of ST segment reduces >0.1 mV; “effective” includes that times of angina attacks reduce by >2/3 or the length, frequency, and severity of angina attacks and chest pain significantly reduce, the depression of ST segment reduces <0.1 mV but >0.05 mV; “ineffective” includes that there is no change or very little change in chest pain and shortness of breath, or the frequency, severity and length of acute angina attacks, the depression of ST segment reduces <0.05 mV. For the systematic review, the outcomes of both “very effective” and “effective” were considered successful treatments.

2.2. Search Strategy

We searched the Cochrane Library (Issue 7, 2011), Chinese Cochrane Centre Controlled Trials Register (to June 2011), Medline (1995 to June 2011), EMBASE (1995 to June 2011), CNKI database (1979 to June 2011), Wanfang Data (1998 to June 2011), and VIP Information (1985 to June 2011) using the following key words: unstable angina, angina, SS, tanshinone IIA, and sodium tanshinone IIA sulfonate, as well as the brand names of the agent. We also searched databases of ongoing trials, including Current Controlled Trials and the UK National Research Register.

We also searched Chinese medicine journals not indexed in the electronic databases. We screened the reference lists of relevant trials and identified reviews. We contacted experts in this field and relevant pharmaceutical companies for additional references or unpublished studies. We restricted the language of publications to English and Chinese.

2.3. Data Collection

Two reviewers (Qiu and Yang) independently screened the titles, abstracts, and key words of each searched article for potentially eligible studies. Reviewers then screened full texts for final eligibility. The full-text articles were retrieved for further assessment if the information given suggests that the study: (1) included patients with unstable angina, (2) compared SS injection with western medication in the presence or absence of cointerventions in both groups, (3) assessed one or more relevant clinical outcome measure such as morality, clinical symptoms, or electrocardiogram (ECG), (4) had clearly outlined criteria for successful treatment and treatment success was not measured in terms of illness severity scores or the intensity of individual symptoms, and (5) used random allocation.

Reviewers independently extracted data from eligible studies, using pilot-tested data extraction forms. Reviewers extracted the following data: age and number of participants in the SS group and the control group, male-female ratio in each group, diagnosis criterion, treatment dosage and duration, side effects, and symptoms that improved after treatments. Important missing data were obtained by contacting article authors whenever possible.

We excluded studies if they (1) included nonunstable angina, used or compared with other Chinese Medicine, (2) used different routine western medications in the trial group and control group, (3) were not randomized trials, (4) had unclear criteria of symptom improvement or data error, (5) were duplicated, or (6) were not conducted on human subjects.

2.4. Risk of Bias

Two reviewers (Qiu and Yang) independently assessed the risk of bias for each trial according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 5.1.0 [44]. The items included the random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other potential threats to validity. Summary assessments of the risk of bias for important outcomes within and across studies was made. Based on Cochrane handbook [44], a study is considered at low risk of bias if there is low risk of bias for all key domains within a study; it is considered to be unclear risk of bias if unclear risk of bias is for one or more key domains within studies at unclear risk of bias across studies; it is considered to be high risk of bias if high risk of bias for one or more key domains within a study is sufficient to affect the interpretation of results across the studies. Disagreements were resolved by discussion and by adjudicated by a third reviewer (Jiang) when necessary.

2.5. Data Analysis

Our comparisons included SS versus western medication and SS plus routine therapy versus routine therapy. We reported risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the pooled binary data, and mean differences (MD) for continuous data. The test of homogeneity was used with a significance level of 0.1. We also used the I-square statistic to assess the heterogeneity. Publication bias was assessed by the funnel plot. We performed sensitivity analysis by using different statistical methods (fixed-effect and random-effects models) for combining data to explore the influence of study quality on effect size.

3. Results

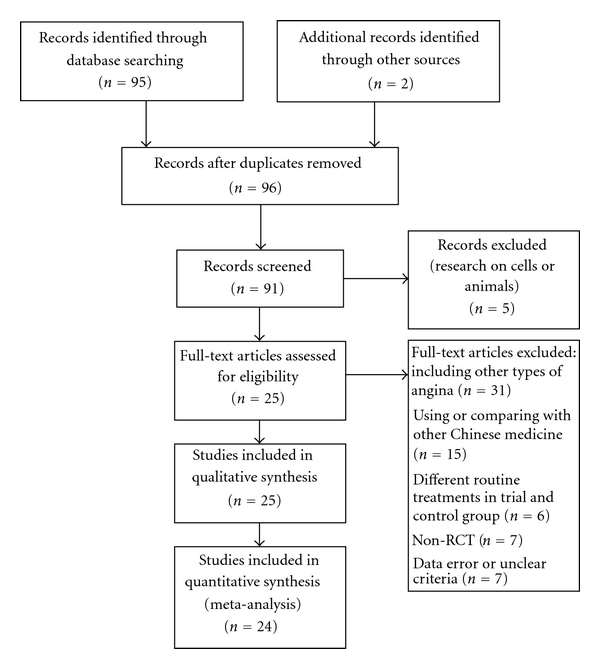

A total of twenty-five trials [19–43], involving 2,377 participants with unstable angina defined as new onset (≤2 months) exertional angina of at least Canadian Cardiovascular Society Classification (CCSC) class III in severity, significant recent increase in frequency and severity of angina, or angina at rest, proved eligible (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart of literature retrieval and selection.

All 25 trials were conducted in China. The treatment duration ranged from 1 to 4 weeks, and the dose from 40 to 80 mg per day. One trial [34] compared SS injection versus isosorbide mononitrate. The other 24 trials compared SS injection plus western medications versus western medications alone. There were no placebo controlled studies. SS injection is given diluted at the point of treatment in 20 mL 25% glucose injection for intramuscular administration or in 250–500 mL 5% glucose injection for intravenous administration. The dosage and administration are not clearly described in every study (Table 1).

Table 1.

Randomized controlled trials of SS injection for unstable angina pectoris.

| Study | Method | N (M : F) | Mean age | Interventions | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhao 2007 [19] | RCT, not blinded Duration: 2 W |

78 (54 : 24) | 62.8 | (1) Isosorbide mononitrate 40 mg (2) SS 40 mg |

(1) clinical symptom improvement, (2) ECG, (3) frequency, duration and intervals of angina attacks |

| Yan et al. 2009 [20] | RCT, not blinded Duration: 4 W |

94 (53 : 41) | 52 | (1) Routine (Aspirin 300 mg–100 mg qd, Enoxaparin, Elantan 50 mg, Betaloc 100 mg) (2) Routine + SS 60 mg |

(1) clinical symptom improvement, (2) ECG, (3) FIB, (4) D-dimer |

| Wang and Hou 2010 [21] | RCT, not blinded Duration: 2 W |

100 (65 : 35) | 62 | (1) Routine (Aspirin, Nitrates, Calcium antagonists, Ozagrel) (2) Routine + SS 40 mg |

(1) clinical symptom improvement, (2) ECG |

| Yang et al. 2010 [13, 22] | RCT, not blinded Duration: 1 W |

64 (35 : 39) | 59 | (1) Routine (Aspirin 100 mg qd, Isosorbide mononitrate 20 mg bid, Metoprolol 25 mg bid) (2) Routine + SS 60 mg |

(1) clinical symptom improvement, (2) ECG, (3) C-reaction protein, (4)IL-6, (5) plasma viscosity, (6) FIB |

| Ge et al. 2010 [23] | RCT, not blinded Duration: 15 D |

60 (39 : 21) | 58 | (1) Routine (Nitrates, Betaloc, anticoagulant and antiplatelet aggregation medication, ACEI, Statins) (2) Routine + SS 60 mg |

(1) clinical symptom improvement, (2) ECG, (3) TC, TG, LDL-C, HDL-C |

| Ge and Zhu 2009 [24] | RCT, not blinded Duration: 2 W |

48 (32 : 16) | 40–80Range | (1) Routine (Aspirin, Betaloc, ACEI, Calcium antagonists, Isosorbide mononitrate, antiplatelet agents, Trimetazidine) (2) Routine + SS 50 mg |

(1) clinical symptom improvement. |

| Hu et al. 2009 [25] | RCT, not blinded Duration: 2 W |

148 | 60 | (1) Routine (Statins, ARB, ACEI, Nitrates, Aspirin, LMWH, Betaloc) (2) Routine + SS 40 mg |

(1) clinical symptom improvement, (2) ECG. |

| Pei and Chen 2009 [26] | RCT, not blinded Duration: 2 W |

71 (48 : 23) | 65 | (1) Routine (Aspirin, Clopidogrel, LMWH, Nitrates, Betaloc, Statins, nondihydropyridine calcium antagonists) (2) Routine + SS 40 mg |

(1) clinical symptom improvement, (2) plasma viscosity, (3) blood viscosity at high/low shear stress, (4) hematocrit. |

| Zuo and Hou 2009 [27] | RCT, not blinded Duration: 2 W |

83 (58 : 25) | 72 | (1) Routine (Aspirin, Betaloc, Nitrates, Statins, LMWH) (2) Routine + SS 40 mg |

(1) clinical symptom improvement, (2) length of angina from attacking to alleviating, (3) length of angina from attacking to vanishing, (4) times of myocardial ischemia onset. |

| Song 2008 [28] | RCT, not blinded Duration: 2 W |

105 | 72 | (1) Routine (Aspirin, Simvastatin, Betaloc, Nitrates, Diltiazem, ARB, ACEI) (2) Routine + SS 60 mg |

(1) clinical symptom improvement. |

| Xu and Su 2008 [29] | RCT, not blinded Duration: 1 W |

74 (40 : 30) | 45–78Range | (1) Routine (Fluvastatin, Aspirin, Betaloc, LMWH) (2) Routine + SS 80 mg |

(1) C-reaction protein, (2) IL-6, (3) P-selectin, (4) PAI-1 |

| Huang et al. 2008 [30] | RCT, not blinded Duration: 2 W |

220 (140 : 80) | 62 | (1) Routine (LMWH, Betaloc, Isosorbide mononitrate, calcium antagonists, Statins, Aspirin) (2) Routine + SS 60 mg |

(1) clinical symptom improvement, (2) ECG, (3) plasma/whole blood viscosity, (4) systolic/diastolic blood pressure, (5) heart rate, (6) hematocrit, (7) Platelet aggregation, (8) FIB. |

| Li et al. 2008 [31] | RCT, not blinded Duration: 2 W |

125 (80 : 45) | 62.41 | (1) Routine (ACEI, vasodilator, antiplatelet agents, anticoagulants) (2) Routine + SS 60 mg |

(1) NO, (2) FMD, (3) ET. |

| Hua et al. 2007 [32] | RCT, not blinded Duration: 2 W |

112 (69 : 43) | 60 | (1) Routine (Aspirin, LMWH, Betaloc, Nitroglycerin, ACEI, Isosorbide mononitrate) (2) Routine + SS 80 mg |

(1) clinical symptom improvement, (2) ECG, (3) plasma viscosity, (4) whole blood viscosity, (5) erythrocyte aggregation, (6) morality, (7) FIB. |

| Wang et al. 2007 [33] | RCT, not blinded Duration: 2 W |

50 (28 : 22) | 48.5 | (1) Routine (Betaloc, Isosorbide mononitrate, Diltiazem, Aspirin) (2) Routine + SS 50 mg |

(1) clinical symptom improvement, (2) ECG, (3) D-dimer, (4) C-reaction protein, (5) plasma viscosity, (6) erythrocyte aggregation, (7) hematocrit. |

| Ma et al. 2007 [34] | RCT, not blinded Duration: 2 W |

59 (37 : 22) | 62.7 | (1) Routine (Betaloc, Aspirin, ACEI, Isosorbide mononitrate, calcium antagonists, anticoagulants,) (2) Routine + SS 40 mg |

(1) clinical symptom improvement, (2) ECG, (3) morality. |

| X. G. Zhang and Y. M. Zhang 2006 [35] | RCT, not blinded Duration: 4 W |

60 (33 : 27) | 62 | (1) Routine (antiplatelet agents, Nitrates, Betaloc, ACEI, Diuretics) (2) Routine + SS 60 mg |

(1) clinical symptom improvement, (2) ECG, (3) systolic/diastolic blood pressure, (4) heart rate, (5) frequency and duration of angina attacks, (6) Premature ventricular contractions in 24 hours. |

| Zhang et al. 2006 [36] | RCT, single blinded Duration: 2 W |

52 | — | (1) Routine (Nitrates, Betaloc, Aspirin) (2) Routine + SS 80 mg |

(1) clinical symptom improvement, (2) ECG. |

| Liu and Yang 2010 [37] | RCT, not blinded Duration: 2 W |

100 (61 : 49) | 65 | (1) Routine (LMWH 6000 U q12h, Nitrates, Simvastatin 20 mg qn, Betaloc, ACEI, Aspirin) (2) Routine + SS 50 mg |

(1) clinical symptom improvement. |

| Yang and Cai 2009 [38] | RCT, not blinded Duration: 4 W |

64 (32 : 32) | 49.5 | (1) Routine (Captopril 25 mg qd, Betaloc 25 mg bid, Isosorbide mononitrate 40 rag qd, Aspirin 0.1 g pd, Simvastatin 25 rag, qn) (2) Routine + SS 60 mg |

(1) clinical symptom improvement, (2) ECG, (3) frequency and duration of angina attacks. |

| Bai and Ding 2007 [39] | RCT, not blinded Duration: 4 W |

80 (42 : 38) | 61 | (1) Routine (Nitrates, Betaloc, ACEI, antiplatelet agents, LMWH) (2) Routine + SS 80 mg |

(1) clinical symptom improvement, (2) ECG. |

| Fang and Wang 2007 [40] | RCT, not blinded Duration: 10 D |

120 (54 : 66) | 74 | (1) Routine (LMWH 5000 U, Nitroglycerin 10 mg) (2) Routine + SS 60 mg |

(1) clinical symptom improvement. |

| Jiang 2004 [41] | RCT, not blinded Duration: 3 W |

156 (82 : 74) | 60.9 | (1) Routine (ACEI, Betaloc) (2) Routine + SS 40 mg |

(1) clinical symptom improvement, (2) C-reaction protein, (3) times of angina attacks daily. |

| Qi and Qu 2008 [42] | RCT, not blinded Duration: 2 W |

68 (38 : 30) | 63 | (1) Routine (Nitrates, Aspirin) (2) Routine + SS 60 mg |

(1) frequency of angina attacks, (2) duration of angina attacks, (3) TC, TG, HDL, LDL. |

| Han and Wang 2011 [43] | RCT, not blinded Duration: 2W |

186 (94 : 92) | 55 | (1) Routine (nitroglycerin 20 mg) (2) Routine + SS 60 mg |

(1) clinical symptom improvement. |

RCT: randomized clinical trial; F: female; M: male; W: week(s); D: day(s); 1: control group; 2: trial group; SS: SS; LMWH: Low molecular weight heparin; ACEI: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB: angiotensin receptor blocker; TC: total cholesterol; TG: Triglyceride; HDL: high density lipoprotein; LDL: low density lipoprotein; NO: nitric oxide; FMD: flow-mediated dilation; ET: endothelin; FIB: fibrinogen; qd: once per day; qn: once per night; bid: twice per day; q12 h: once every 12 hours.

Two trials [33, 35] reported data on mortality. Most trials reported improvement of clinical symptoms and ECG.

All studies were at high risk of bias (Table 2). One trial [33] described the method of randomization in detail, and the method was also appropriate. All the other studies did not report information on the allocation concealment. One trial [37] mentioned it is a single-blinded study, and none were double blinded. Loss to followup was recorded in none of the studies. No studies conducted intention-to-treat analysis.

Table 2.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies.

| Study | Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding | Incomplete outcome data | Selective reporting | Free of other bias | Summary assessments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhao 2007 [19] | U | U | H | U | U | H | H |

| Yan et al. [20] 2009 | U | U | H | U | U | H | H |

| Wang and Hou 2010 [21] | U | U | H | U | U | H | H |

| Yang et al. 2010 [22] | U | U | H | U | U | H | H |

| Ge et al. 2010 [23] | U | U | H | U | U | H | H |

| Ge and Zhu 2009 [24] | U | U | H | H | U | H | H |

| Hu et al. 2009 [25] | U | U | H | U | U | H | H |

| Pei and Chen 2009 [26] | U | U | H | U | U | H | H |

| Zuo and Hou 2009 [27] | U | U | H | U | U | H | H |

| Song 2008 [28] | U | U | H | H | U | H | H |

| Xu 2008 [29] | U | U | H | L | U | H | H |

| Huang et al. 2008 [30] | U | U | H | U | U | H | H |

| Li et al. 2008 [31] | U | U | H | U | U | H | H |

| Hua et al. 2007 [32] | L | L | H | U | U | H | H |

| Wang et al. 2007 [33] | U | U | H | U | U | H | H |

| Ma et al. 2007[34] | U | U | H | U | U | H | H |

| X. G. Zhang and Y. M. Zhang 2006 [35] | U | U | H | U | U | H | H |

| Zhang et al. 2006 [36] | U | U | H | H | U | H | H |

| Liu and Yang 2010 [37] | U | U | H | H | U | H | H |

| Yang and Cai 2009 [38] | U | U | H | U | U | H | H |

| Bai and Ding 2007 [39] | U | U | H | H | U | H | H |

| Fang and Wang 2007 [40] | U | U | H | H | U | H | H |

| Jiang 2004 [41] | U | U | H | U | U | H | H |

| Qi and Qu 2008 [42] | U | U | H | U | U | H | H |

| Han and Wang 2011 [43] | U | U | H | H | U | H | H |

L: low risk of bias, U: unclear, H: high risk of bias.

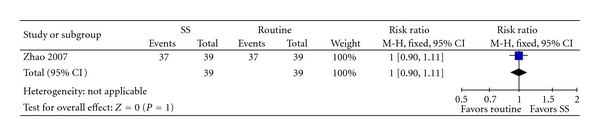

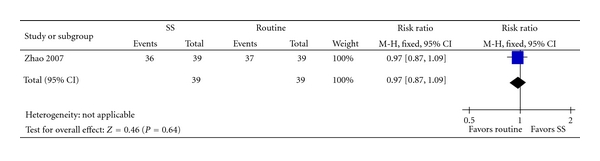

3.1. SS versus Western Medications

One trial [34] compared SS alone versus western medicine. There were no significant differences in improvement of clinical symptoms (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.11, Figure 2) and improvement in ECG (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.09, Figure 3).

Figure 2.

SS versus Isosorbide, outcome: clinical symptom improvement.

Figure 3.

SS versus Isosorbide, outcome: ECG.

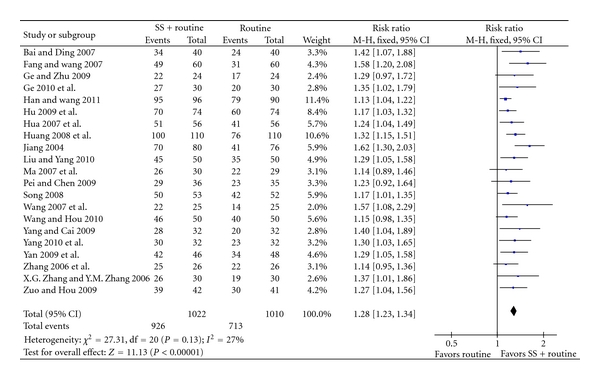

3.2. SS + Western Medications versus Western Medications

Two trials [33, 35] comparing SS plus western medications versus western medications reported only one sudden death in the western medication group [33] (RR 0.50; 95% CI 0.02 to 12.13).

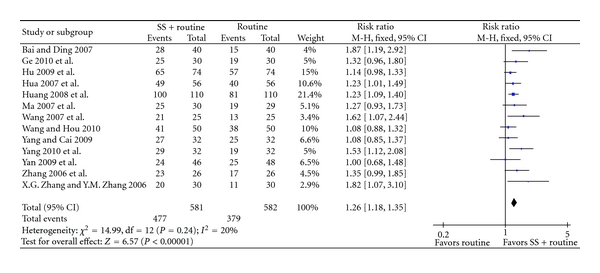

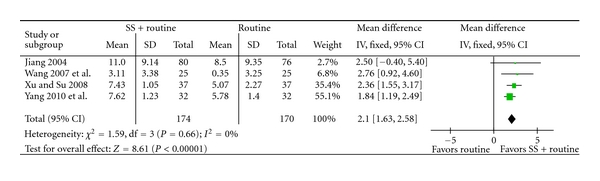

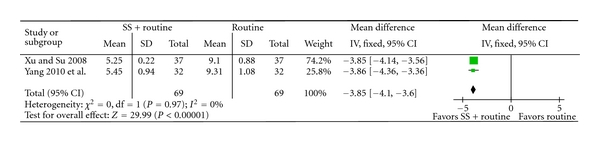

Sodium plus western medications achieved statistically significant improvement of clinical symptoms than western medications alone (RR 1.28, 95% CI 1.23 to 1.34, Figure 4), and improvement of ECG (RR 1.26, 95% CI 1.18 to 1.35, Figure 5), C-reaction protein (mean difference 2.10, 95% CI 1.63 to 2.58, Figure 6), and IL-6 (mean difference −3.85, 95% CI −4.10 to −3.60, Figure 7).

Figure 4.

SS + routine therapy versus routine therapy, outcome: clinical symptom improvement.

Figure 5.

SS + routine therapy versus routine therapy, outcome: ECG.

Figure 6.

SS + routine therapy versus routine therapy, outcome: C-reaction Protein.

Figure 7.

SS + routine therapy versus routine therapy, outcome: IL-6.

Of the 25 trials, 7 reported adverse events. In the routine treatment group, adverse reactions included headache, dizziness, facial flushing, fatigue, and bruises at injection site. Totally 32 cases were reported. In the SS + routine treatment group, adverse reactions included facial flushing, dizziness, bruises, tension or swell at injection site, blood in sputum, and gum bleeding. Totally 13 cases were reported. No severe adverse events were found and no treatment was stopped because of adverse events.

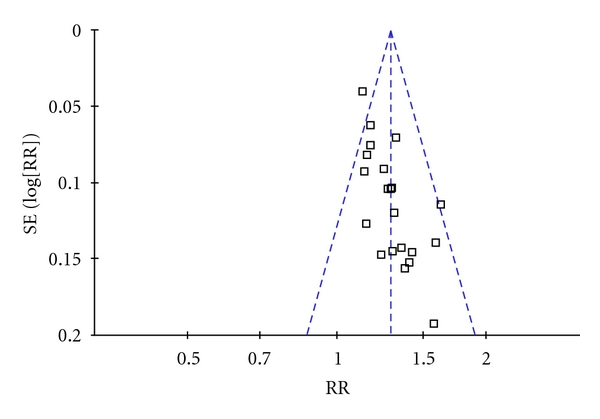

Because the funnel plot seems symmetric, the possibility that the result of this review might be misled by publication bias is likely to be little (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Funnel plot of comparison: SS plus routine therapy versus routine therapy, outcome: clinical symptom improvement. (Each dot represents one study. All the dots are conforming to a triangular form, meaning that publication bias is low).

4. Discussion

SS injection appeared an effective and safe treatment option for unstable angina pectoris. The present results showed that SS plus routine therapies appear to be more effective than western medications alone.

However, trials are at high risk of bias, making the findings less compelling. Except for one trial, none of the other trials reported the method of randomization. Although all trials claimed randomization, they failed to provide enough information to judge whether the randomization procedures had been carried out properly. No multicenter, large-scale RCTs were identified. No dropouts and withdrawals were described. No placebo control was used and none of the trials were of double blind. Routine therapy varied from trial to trial. The dosage and administration of control and trial therapies are not clearly described in every study.

The main outcomes from the included 25 trials were the improvement of clinical symptoms and ECG. The primary outcome measure was reported in only two trials. There is lack of data from RCTs on clinically relevant outcomes from long-term followup such as mortality and health-related quality of life.

18 out of 25 trials referred to observation of side effects. There were less side events in the SS injection group. None of the events were severe and no patients dropped out because of the side effects. SS injection appears to be relatively safe.

We have conducted comprehensive searches. However, only trials published in English and Chinese were indentified. Unpublished studies were found but none of them met the inclusion criteria. Since all of the trials were of small size with positive results and were conducted China, geographic biases may be induced.

The poor evidence does not allow any conclusion regarding the effectiveness of SS, and none of the included trials were ideally suited to investigate the effectiveness of SS in treating unstable angina. While SS is a widely used therapy for unstable angina in China, the results of the present review suggest that high-quality controlled trials are required for assessment.

5. Conclusions

Compared with western medications alone, SS combined with western medications was of more benefits for patients with unstable angina with fewer side effects. However, the methodological concerns, such as allocation concealment, lack of blinding, lack of information on the hazards of treatment, and the risk of publication bias, make it difficult to determine the role of SS injection in management of unstable angina.

Considering the strength of the evidence, more rigorously designed, randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trials are required for assessing the effects of SS injection before SS injection can be recommended routinely. Some aspects should be specially considered, including methodological improvement (such as details on the methods of randomization and the allocation concealment, blinding and placebo control, dropouts and withdrawals), adverse reactions, and reporting clinically outcomes from long-term followup such as mortality and health-related quality life.

Disclosure

No grants or funding were provided for the performance of this study.

Conflict of Interests

There is no conflict of interests with any financial organization regarding what is discussed in the paper.

References

- 1.American Heart Association. ACC/AHA Management of Patients with Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction—Pocket Guideline, 2011, http://my.americanheart.org/idc/groups/ahaecc-internal/@wcm/@sop/documents/downloadable/ucm_423798.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.American Heart Association. ACC/AHA 2007 guideline revision of management of patients with unstable angina/non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2007;116(7):803–877. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.181940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bär FW, Verheugt FW, Col J, et al. Thrombolysis in patients with unstable angina improves the angiographic but not the clinical outcome: results of UNASEM, a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial with anistreplase. Circulation. 1992;86(1):131–137. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schreiber TL, Rizik D, White C, et al. Randomized trial of thrombolysis versus heparin in unstable angina. Circulation. 1992;86(5):1407–1414. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.5.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braunwald E. Effects of tissue plasminogen activator and a comparison of early invasive and conservative strategies in unstable angina and non-Q-wave myocardial infarction: results of the TIMI IIIB trial. Circulation. 1994;89(4):1545–1556. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.4.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou L, Zuo Z, Chow MSS. Danshen: an overview of its chemistry, pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, and clinical use. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2005;45(12):1345–1359. doi: 10.1177/0091270005282630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pharmacopoeia Committee of China. Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China. Beijing, China: China Medico-Pharmaceutical Science & Technology Publishing House; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lam BYH, Lo ACY, Sun X, Luo HW, Chung SK, Sucher NJ. Neuroprotective effects of tanshinones in transient focal cerebral ischemia in mice. Phytomedicine. 2003;10(4):286–291. doi: 10.1078/094471103322004776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niu XL, Ichimori K, Yang X, et al. Tanshinone II-A inhibits low density lipoprotein oxidation in vitro. Free Radical Research. 2000;33(3):305–312. doi: 10.1080/10715760000301471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He LN, Yang J, Jiang Y, Wang J, Liu C, He SB. Protective effect of tanshinone on injured cultured PC12 cells in vitro. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2001;26(6):413–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang AM, Sha SH, Lesniak W, Schacht J. Tanshinone (Salviae miltiorrhizae extract) preparations attenuate aminoglycoside-induced free radical formation in vitro and ototoxicity in vivo. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2003;47(6):1836–1841. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.6.1836-1841.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao BL, Jiang W, Zhao Y, Hou JW, Xin WJ. Scavenging effects of Salvia miltiorrhiza on free radicals and its protection for myocardial mitochondrial membranes from ischemia-reperfusion injury. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology International. 1996;38(6):1171–1182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang P, Jia Y-H, Li J, Li L-J, Zhou F-H. Study of anti-myocardial cell oxidative stress action and effect of tanshinone IIA on prohibitin expression. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2010;30(4):259–264. doi: 10.1016/s0254-6272(10)60053-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang R, Liu A, Ma X, Li L, Su D, Liu J. Sodium tanshinone IIA sulfonate protects cardiomyocytes against oxidative stress-mediated apoptosis through inhibiting JNK activation. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 2008;51(4):396–401. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181671439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun D, Shen M, Li J, et al. Cardioprotective effects of tanshinone IIA pretreatment via kinin B2 receptor-Akt-GSK-3β dependent pathway in experimental diabetic cardiomyopathy. Cardiovascular Diabetology. 2011;10, article 4 doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-10-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shan H, Li X, Pan Z, et al. Tanshinone MA protects against sudden cardiac death induced by lethal arrhythmias via repression of microRNA-1. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2009;158(5):1227–1235. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00377.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi Y, Li XY, Wang TY, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics studies of Tanshinone IIA and tanshinone IIA sulfonate. Chinese Journal of Pharmaceutics. 2009;7(3):143–153. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Database of State Food and Drug Administration of China, 2011, http://www.sfda.gov.cn.

- 19.Zhao YH. Therapeutic observation of sodium tanshinone IIA sulfonate injection treating unstable angina. Practical Geriatrics. 2007;21(3):212–213. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yan FF, Liu YF, Liu Y, Zhao YX. SS injection could decrease fibrinogen level and improve clinical outcomes in patients with unstable angina pectoris. International Journal of Cardiology. 2009;135(2):254–255. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang AP, Hou Q. Tanshinone combined with ozagrel treating unstable angina. Taishan Health Journal. 2010;34:20–21. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang N, Ren FX. SS for unstable angina pectoris: a study of clinical application. China Modern Doctor. 2010;48(21):47–49. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ge HZ, Cheng YN, Xun HY. Clinical observation of SS treating unstable angina. Chinese Journal of Difficult and Complicated Cases. 2010;9(3):201–202. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ge JX, Zhu DF. Clinical analysis of 48 patients with unstable angina treated by trimetazidine combined with sodium tanshione IIA sulfonate. Guide of Chinese Medicine. 2009;7(13):71–72. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu HL, Ji YJ, Ye SH. Observation of therapeutic effect of sodium tanshione IIA sulfonate injection treating unstable angina. Chinese Journal of Ethnomedicine and Ethnopharmacy. 2009;11, article 71 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pei X, Chen G. 36 patients with unstable angina treated with tanshione IIA sulfonate combined with Western medications. Shanxi Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2009;30(10):1276–1278. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zuo H, Hou WB. Analysis of therapeutic effect of tanshione IIA sulfonate injection combined with low-molecular-weight heparin treating elderly patients with unstable angina. Chinese Community Doctors. 2009;11(13):18–19. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Song CL. Clinical research on tanshione IIA sulfonate combined with low-molecular-weight heparin treating 53 elderly patients with unstable. The Journal of Medical Theory and Practice. 2008;21(3):289–290. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu GP, Su H. The affection of tanshinone to the inflammatory factors’ level in unstable angina patients. Hainan Medical Journal. 2008;19(3):31–33. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang XT, Pu XJ, Li X, Chen XY, Wang M, Qi XC. Observation of the therapeutic effect of SS treating unstable angina. Ningxia Medical Journal. 2008;30(1):51–52. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li L, Sun XW, Wu ZY, Ren CJ, Wei ZX. Effect on function of vascular endothelium in patient with unstable-angina pectoris. Journal of Jining Medical College. 2008;31(3):288–290. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hua N, Tang FK, Niu WX, Wang L, Di Q. Sodium tanshinone IIA sulfonate combined with low-molecular-weight heparin sodium in treatment of unstable angina pectoris. Medical Journal of the Chinese People’s Armed Police Forces. 2007;18(3):195–198. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang QL, Deng XJ, Li XQ, Chen XT. Effect of sodium tanshinone IIA sulfonate injection on CRP and D-dimer level in patients with unstable angina. Journal of New Chinese Medicine. 2007;39(7):16–17. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma JH, Xiong WP, Wan FW, Hua M. Research on sodium tanshinone IIA sulfonate injection combined with isosorbide mononitrate treating unstable angina. China Modern Doctor. 2007;45(14):97–105. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang XG, Zhang YM. Therapeutic observation of tanshinone IIA sulfonate treating unstable angina. Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine on Cardio-/Cerebrovascular Disease. 2006;4(10):857–858. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang HR, Sun L, Li YS, Jin YK. Therapeutic observation of tanshinone IIA sulfonate injection treating unstable angina. Tianjin Pharmacy. 2006;18(6):31–32. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu HL, Yang XH. Therapeutic observation of tanshinone IIA sulfonate injection treating unstable angina. Medical Innovation of China. 2010;7(13):p. 37. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang HL, Cai RJ. Clinical research on tanshinone IIA sulfonate injection injection treating unstable angina. Chinese Health Care. 2009;17(17):716–717. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bai LJ, Ding HG. Therapeutic observation of tanshinone IIA sulfonate injection treating 80 patients with unstable angina. Journal of China Clinical Medical Research. 2007;13(13):1813–1814. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fang J, Wang Q. Randomized controlled research of tanshinone IIA sulfonate treating 60 elderly patients with unstable angina. Central Plains Medical Journal. 2007;34(15):p. 81. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiang KR. Clinical research on nuo xin kang treating 80 patients with unstable angina. Chinese Journal of Current Clinical Medicine. 2004;2(6):p. 908. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qi XD, Qu BZ. Therapeutic observation of tanshinone IIA sulfonate injection treating unstable angina. Journal of China Medicine. 2008;3(13):p. 65. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Han XL, Wang SH. Clinical observation of tanshinone IIA sulfonate injection treating 96 patients with unstable angina. Hebei Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2011;33(3):472–473. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011, http://www.cochrane-handbook.org.