Abstract

The study of the pearl oyster Pinctada fucata is key to increasing our understanding of the molecular mechanisms involved in pearl biosynthesis and biology of bivalve molluscs. We sequenced ∼1150-Mb genome at ∼40-fold coverage using the Roche 454 GS-FLX and Illumina GAIIx sequencers. The sequences were assembled into contigs with N50 = 1.6 kb (total contig assembly reached to 1024 Mb) and scaffolds with N50 = 14.5 kb. The pearl oyster genome is AT-rich, with a GC content of 34%. DNA transposons, retrotransposons, and tandem repeat elements occupied 0.4, 1.5, and 7.9% of the genome, respectively (a total of 9.8%). Version 1.0 of the P. fucata draft genome contains 23 257 complete gene models, 70% of which are supported by the corresponding expressed sequence tags. The genes include those reported to have an association with bio-mineralization. Genes encoding transcription factors and signal transduction molecules are present in numbers comparable with genomes of other metazoans. Genome-wide molecular phylogeny suggests that the lophotrochozoan represents a distinct clade from ecdysozoans. Our draft genome of the pearl oyster thus provides a platform for the identification of selection markers and genes for calcification, knowledge of which will be important in the pearl industry.

Keywords: pearl oyster, Pinctada fucata, draft genome

1. Introduction

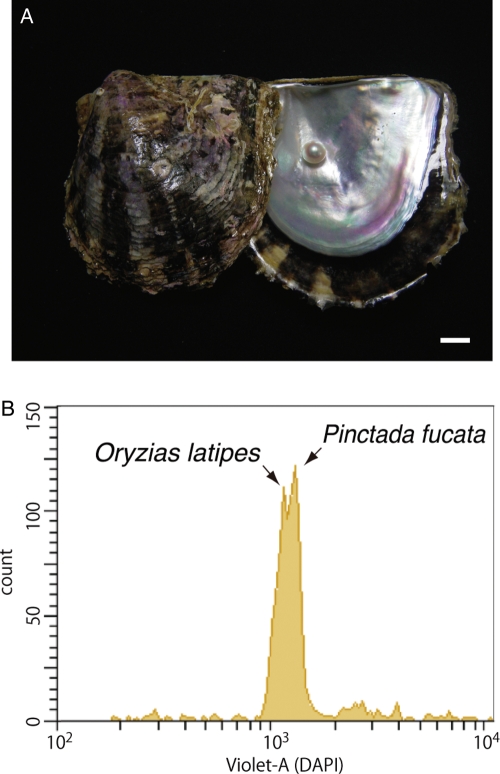

We sequenced the genome of the pearl oyster Pinctada fucata (Fig. 1A) with two major goals in mind. First, we sought to obtain genomic information that could be used in future studies of the molecular mechanisms underlying the biosynthesis of pearl in the bivalve mollusc. Pearls are of significant value industrially and as jewels; better understanding of the mechanism is essential to further improvement of pearl production in the fisheries industry. To date, mechanisms involved in the nacreous layer formation in the pearl oyster have been studied extensively.1–4 The shell of pearl oysters consists of two distinct structures: inner nacreous layers composed of aragonite and outer prismatic layers composed of calcite. An intriguing question in the field of bio-mineralization research is how the two polymorphs of calcium carbonate are produced in the same organism. Previous studies that explored these bio-mineralization processes identified and characterized a wide variety of genes and proteins; their functions have also been examined in association with shell formation.4–6 For example, Kinoshita et al.7 conducted an expressed sequence tag (EST) analysis of P. fucata genes expressed in the pallial mantle, which forms the nacreous layer, and in the mantle edge, which forms the prismatic layer. That study generated 29 682 unique sequences, from which the authors succeeded in identifying multiple genes, some novel, that may play roles in the pearl formation. In spite of such extensive studies, however, we still have only a limited understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying pearl oyster shell formation. Decoding the genome of pearl oysters is therefore essential for future genome-wide analyses of these mechanisms.

Figure 1.

(A) The pearl oyster P. fucata and its pearl. Scale bar, 1 cm. (B) Flow cytometry of a mixture of sperm from Pinctata and Oryzias. The Pinctata genome, estimated to be ∼1150 Mb in size, is slightly larger than the Oryzias genome (∼1100 Mb).

Our second goal was to improve our overall understanding of the biology of bivalve molluscs, specifically those features that characterize molluscs and their evolution among metazoans and/or lophotrochozoans.8–10 Lophotrochozoa is one of the largest clades of bilaterians, together with the Ecdysozoa and Deuterostomia. The core group of Lophotrochozoa includes molluscs, annelids, nemertines, lophophorates, and platyhelminths. Since these core groups show the greatest variety of adult body plans, the relationships among the lophotrochozoan taxa are still controversial.11 Although adult morphology varies vastly across the group, many core lophotrochozoans share spiral cleavage and a trochophore larval stage. Understanding the proposed repeated losses of both spiral cleavage and trochophore larvae in the Lophotrochozoa clade requires comparative studies of genes involved in the formation of body plans, performed on the basis of full genomic information.

The phylum Mollusca itself is one of the most diverse animal groups; mollusc species exhibit a range of morphologies and sizes, from microscopic bivalves to 1-m long giant clams.8–10 The phylum includes ∼100 000 described and living species. Due to their hard exoskeletal shell, molluscs appear in the fossil record dating from the Cambrian era, and the major bivalves were established by the Middle Ordovician.12,13 However, the search for bivalve ancestors has proved less straightforward, mainly due to differing interpretations of the extant microfossils. Mollusca comprise seven or eight major lineages, and three majors are Bivalvia (clams and oysters), Gastropoda (snails and slugs), and Cephalopoda (squids and octopus). A recent phylogenetics of evolutionary relationship among Mollusca by Kocot et al.14 showed a sister-taxon relationship between Bivalvia and Gastropoda.

The class Bivalvia includes ∼20 000 living species; their developing embryos pass through two larval stages, trochophore and verliger. Bivalves are characterized by their possession of two separate shells, called valves. It is thought that during evolution of molluscs leading to the bivalves, a single dorsal shell in the ancestor was doubled. Recently, Kin et al.15 examined genes involved in this prominent morphological transition in the Japanese spiny oyster Saccostrea kegaki. They found that a member of transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) family, dpp, is expressed only in the cells along the dorsal midline, and plays an important role in establishing the characteristic shape of the bivalve shell anlagen.

The genome contains all the genetic information of a given organism; therefore, sequenced genomes provide an invaluable basis for studying every aspect of biology. Since the first sequencing of a metazoan genome, the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans16 in 1998, ∼35 metazoan genome sequences have been reported. However, there is an apparent bias in the selection of targeted metazoan genomes. In contrast to vertebrates,17–19 basal chordates,20,21 ecdysozoans including Drosophila melanogaster22 and Apis mellifera,23 and cnidarians,24–26 placozoans,27 and the sponge,28 there have been no reports of sequenced genomes in lophotrochozoans, although planarians, annelids, and gastropod molluscs have been the subjects of their own genome projects.

With the aims described, in the context of the current status of genome sequencing efforts, we sequenced the genome of the pearl oyster P. fucata. Because of its comparatively large size, the assembly so far obtained is still comparatively short, but the draft genome will provide a platform sufficient for exploring the molecular basis of pearl biosynthesis.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Biological material

Pinctada fucata (Fig. 1A) cultured at the Pearl Research Institute of Mikimoto Co., Ltd, Shima, Japan, was used in the present study.

2.2. Number of chromosomes and genome size

The number of chromosomes was determined by chromosome preparation from nuclei of embryonic cells at the blastula and gastrula stages. The chromosomes were spread according to the method described by Shoguchi et al.29 and stained with Giemsa. The number was confirmed from a total of 25 spreads.

The genome size of P. fucata was estimated by flow cytometry using sperm nuclei from the same specimen used in the genome sequencing.30 Sperm nuclei were treated with a DAPI flow cytometry kit and a BD Cycletest Plus DNA Reagent Kit (BD Biosciences) and analysed on a BD FACSAria II cell sorter (BD Biosciences). The nuclear suspension was confirmed using a fluorescence microscope. The sperm of Takifugu rubripes (365 Mb),18 Oryzias latipes31 (1100 Mb), and Danio rerio (2300 Mb)32 were used for comparison. Runs were performed with stained sperm of each species and also with mixtures of P. fucata sperm with sperm from T. rubripes, O. latipes, or D. rerio. The genome sizes of Takifugu, Oryzias, and Danio were also compared with the published values in order to detect machine-related and/or other technical problems.

2.3. Genome sequencing and assembly

The sperm was obtained from a single male during the spawning season, autumn of 2010. The sperm DNA was fragmented, libraries were prepared and sequenced by whole-genome shotgun (WGS) and paired-end read protocols (4 and 10 kb libraries) using a Roche 454 GS-FLX,33 and by WGS and mate-pair protocols (3 and 10 kb libraries) using an Illumina Genome Analyzer IIx (GAIIx) instruments.34

The 454 WGS and paired-end reads were assembled de novo by GS De Novo Assembler version 2.6 (Newbler, Roche).33 Subsequent scaffolding of the Newbler output was performed by SSPACE35 by adding the Illumina mate-pair sequence information.

2.4. Transcriptome analyses

RNA was isolated from nine different stages, from eggs to D-stage larvae. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen) and purified using DNase and an RNeasy micro kit (QIAGEN). mRNA was amplified using a MessageAmp II aRNA Amplification Kit (Ambion). Transcriptome libraries were sequenced using the 454 GS-FLX. Transcriptome data were also obtained from the mantle edge, pallial muscle, and pearl sac.7 All sequences were poly-A trimmed and assembled by Newbler.

2.5. Gene prediction

A set of gene model predictions (the P. fucata Gene Model version 1.0) was generated using AUGUSTUS 2.0.4.36 All of the following were incorporated as AUGUSTUS ‘hints’: all raw transcriptome reads (except ribosomal RNA sequences); assembled ESTs of P. fucata; bivalve EST data sets available on NCBI; and putative protein-coding loci found using BLASTX on scaffolds present in the proteomes of D. melanogaster, Mus musculus, and Homo sapiens. Next, we aligned models to an annotated transposable element (TE) database using BLASTP (1e−10) to filter out genes that overlapped TE proteins over >60% of their exonic length. All the EST sequences that encode putative full-length proteins were screened by PASA,37 and ∼200 EST assemblies randomly selected from the screened ESTs were used for AUGUSTUS training. The gene models were created by running AUGUSTUS on repeat-masked genome sequences produced by RepeatMasker.38

2.6. TEs and repetitive sequences

Tandem repeats were detected using Tandem Repeat Finder (version 4.04),39 and then classified using Tandem Repeats Analysis Program (version 1.1).40 A de novo repeats library was generated by RepeatScout (version 1.0.5).41 The repeats were annotated based on BLAST hits to Repbase TE library (version 16.05).42 Transposons and SINEs (short interspersed nuclear elements) in the scaffold were identified using CENSOR (version 4.2)43 by BLAST search against the P. fucata repeat library.

2.7. Gene annotation and identification of genes in the genome

Three approaches, individually or in combination, were used to annotate the protein-coding genes in the P. fucada genome. Our primary approach to the identification of putative orthologues of P. fucada genes was reciprocal BLAST analysis. This was carried out on the basis of mutual best-hit in the BLAST analyses of human, mouse, or Drosophila genes against the P. fucada gene models (BLASTP) or the assembly (TBLASTN).

A second approach, used in the case of gene-encoding proteins with one or more specific protein domains, was to screen the merged models against the Pfam database (Pfam-A.hmm, release 24.0; http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk)44, which contains ∼11 000 conserved domains, using HMMER (hmmer3).45

2.8. Genome browser

A genome browser has been established using the assembled genome sequences using the Generic Genome Browser (GBrowse), version 2.17.46

2.9. Mitochondrial genome

Contigs containing mitochondrial genes were searched by BLASTN and BLASTX using bivalvian mitochondrial genes as queries. Mitochondrial protein-coding sequences thereby obtained were confirmed using open reading frame (ORF) Finder (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/gorf/) using the invertebrate mitochondrial genetic code as a reference. The tRNA genes were annotated using DOGMA,47 ARWEN48 with default settings, and tRNAscan-SE 1.249 with a COVE cut-off score of 1.

We also performed reconstruction and extension of the mitochondrial DNA sequences, using the following strategy: first, mitochondrial gene sequences obtained above were set as ‘seeds’. A total of 454 raw reads that yielded BLAST hits against the seed sequences were picked up and assembled using Newbler (version 2.6). Assembled sequences were BLAST searched against mitochondrial sequences, and BLAST-hit sequences were used as seeds for the next round of BLAST-assembly workflow. This process was replicated until the contigs did not extend any further.

2.10. Molecular phylogeny

Based on the study by Philippe et al.50 in which only genes with a moderate rate of amino acid substitution were targeted for molecular phylogeny, we performed mutual best-hit BLAST analyses against three metazoans (H. sapiens, D. melanogaster, and P. fucata) and selected a set of 2087 orthologous genes. Next, the orthologous gene set was surveyed in the genomes of the beetle Tribolium castaneum, the mosquito Anopheles gambiae, the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum, the water flea Daphnia pulex, the lancelet Branchiostoma floridae, the tunicate Ciona intestinalis, the fugu T. rubripes, the zebrafish D. rerio, the anole Anolis carolinensis, the chicken Gallus gallus, the opossum Monodelphis domestica, and the mouse M. musculus. The sea anemone Nematostella vectensis and the coral Acropora digitifera were also examined as outgroup. Most of the protein sequences were retrieved from Refseq (NCBI) through GenomeNet (http://www.genome.jp), except for N. vectensis and D. pulex (Joint Genome Institute, http://genome.jgi-psf.org).

In order to avoid mixing paralogous genes, we performed a BLAST search under stringent conditions (E-value cut-off at 1e−50). Genes detected in all species were aligned using ClustalW,51 and poorly aligned regions were excluded using Gblocks.52 Next, Neighbor Joining tree of each gene was generated with ClustalW to evaluate the branch length of the trees. Each gene with moderate branch length was concatenated and used for molecular phylogenetic analyses. We ran RAxML 7.2.853 for maximum likelihood analyses using the WAG+CAMMA+F model for the whole data matrix. Bootstrap analysis was performed on the basis of 100 replicates.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Number of chromosomes and genome size

As a part of the P. fucata genome project, we examined the number of chromosomes and estimated the genome size. The chromosome number of P. fucata was previously reported by Wada54 to be 2n= 28. We confirmed this number of chromosomes (Supplementary Fig. S1).

The genome size of P. fucata was estimated by comparing genomes of other metazoans with reported size estimation. We found that the genome size of P. fucata was a little larger than that of the medaka O. latipes (Fig. 1B; Supplementary Fig. S2D and E). Since the genome size of O. latipes has been calculated to be ∼1100 Mb,31 we estimated the P. fucata genome to be ∼1150 Mb in size. According to the Animal Genome Size Database, Release 2.0 (http://www.genomesize.com), the genome sizes of bivalves are between 1200 and 2100 Mb. Thus, the P. fucata genome is comparatively small among bivalves.

3.2. Genome sequencing and assembly

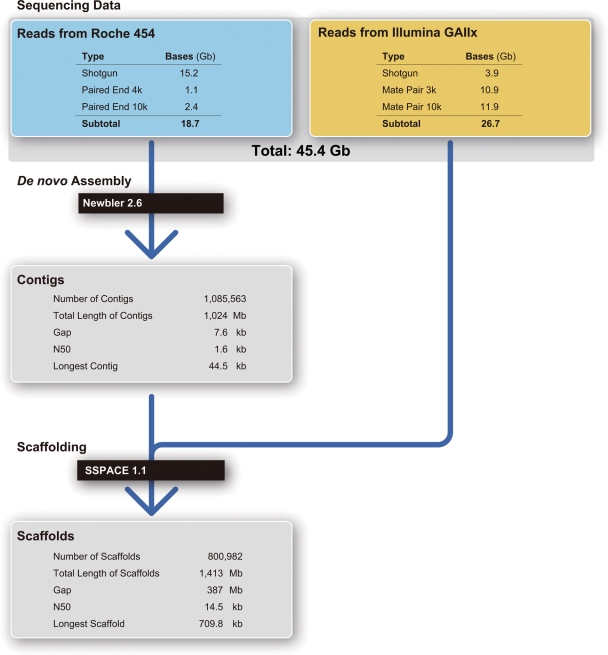

Figure 2 shows a flow chart of sequencing and assembly; details of the sequenced and assembled data are presented in Supplementary Table S1. The Roche 454 sequencing platform generated a total of 44.5 M WGS reads, yielding 15.2 Gb of sequence (average read length was 341 bp) and 11.6 M paired-end reads (the insert sizes were 4 and 10 kb, respectively; average read lengths were 286 and 309 bp, respectively), yielding 3.5 Gb of sequence. In addition, the Illumina platform generated 76 M WGS reads (3.9 Gb) and 22.8 Gb mate-pair sequences (10.9 Gb for the 3-kb library and 11.9 Gb for the 10-kb library). A total of 45.4 Gb were sequenced. Based on the genome size estimation of 1.15 Gb (see above), this corresponds to ∼40-fold coverage of the P. fucata genome.

Figure 2.

Flow chart for sequencing and assembly of the P. fucata genome.

The 454 WGS and paired-end reads were assembled (Fig. 2). A total of 18.7 Gb of sequence, which corresponds to 16.3× of the estimated genome size, was used at this stage. The reads were first screened and trimmed using the built-in filter module of Newbler in order to remove potential primer and adaptor contamination. About 17 Gb were used for the subsequent assembly procedure; 14 Gb was successfully aligned to form contigs. The assembled genome contained 1 085 563 contigs with an N50 size of 1629 bp (Table 1; Supplementary Table S1; Fig. 2). The longest contig was 44.5 kb, and ∼40% of the sequences were covered by contigs of >2 kb in length (Supplementary Table S1). The assembled genome contained a total of 1024 Mb, which is comparable with the estimated genome size (Supplementary Table S1; Fig. 2). Gaps in the contig assembly were only 7.6 kb (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Summary of the Roche 454 and Illumina GAIIx data used for assembling P. fucata genome sequences

| Used data |

Assembly |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Totalsequences (Gb) | Number of reads(million) | Average readlength | Estimatedcoverage | Contig |

Scaffold |

|||

| Number | N50 (bp) | Number | N50 (bp) | |||||

| 454 | ||||||||

| Shotgun | 15.2 | 44.5 | 341 | 16.3x | 1 085 563 | 1629 | 800 982 | 14 455 |

| 4 kb paired enda | 1.1 | 3.8 | 286 | |||||

| 10 kb paired enda | 2.4 | 7.8 | 309 | |||||

| GAIIx | ||||||||

| Shotgun | 3.9 | 76 | 50 | 26.7x | ||||

| 3 kb mate-pair | 10.9 | 216 | 50 | |||||

| 10 kb mate-pair | 11.9 | 238 | 50 | |||||

aEach 454 raw reads were separated into ‘forward’ and ‘reverse’.

Subsequent scaffolding of the 1 085 563-contig Newbler output was performed using the Illumina mate-pair information. The final assembly contained 800 982 scaffolds with an N50 size of 14.5 kb (Table 1; Supplementary Table S2; Fig. 2). The total length of scaffolds was 1029 Mb (a total of 1413–384 Mb gaps; Fig. 2). The size of the longest scaffold was 709.8 kb; three scaffolds extended over 500 kb in length. Approximately 44% of the sequences were covered by scaffolds of >20 kb in length (Supplementary Table S2). The scaffolds included ∼384-Mb gaps containing unknown sequences (Fig. 2); gap size distribution is shown in Supplementary Table S3.

3.3. Examination of possible causes of incomplete genome assembly

As described above, in spite of our considerable sequence coverage (∼40-fold) of the P. fucata genome, its contig N50 and scaffold N50 were comparatively small. Possible reasons for this include the large genome size, the presence of various types of repetitive sequence (see Section 3.9), and high allelic polymorphism or heterozygosity. We examined whether allelic polymorphism affected the assembly; in addition, we examined the assembly of mitochondrial genome in this context. These analyses are described below.

3.3.1. Allelic polymorphism

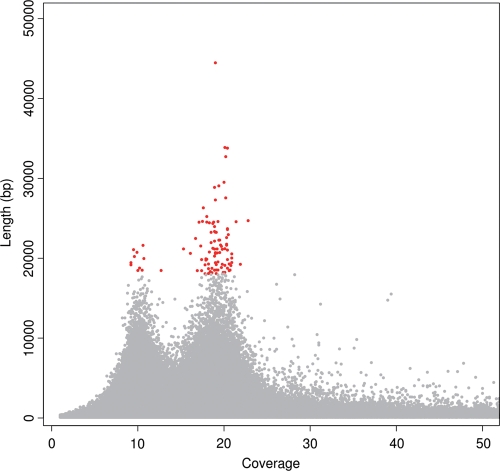

We analysed the relationship between contig sizes and coverage depth. In haploid genomes, or diploid genomes with very low heterozygosity, this relationship would take the form of a Gaussian distribution curve with a single peak. On the other hand, in the case of a diploid genome with high allelic polymorphism, the plot would appear as a curve with two peaks with approximately double coverage−depth relation. As shown in Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. S3, a curve with two distinct peaks appeared in the graph, one at around ∼18× the coverage depth and the other at ∼10×. Most of the 100 longest contigs were present in the former group, indicating that this region consisted of sequences with lower polymorphism. This notion is also supported by the fact that the average coverage depth of this region (18.2×) was similar to the overall sequence coverage for contig construction (16.3×).

Figure 3.

Distribution of the contig lengths (Y-axis) and their coverage depth (X-axis) in the current P. fucata genome assembly. A coverage range between 1 and 50 is shown for convenience. The 100 longest contigs (44–18 kb) are plotted as red dots; all others are plotted as gray dots. Two significant peaks appeared near coverage depths 10 and 20, respectively. The difference in read coverage of the contigs is likely to be derived from heterozygosity in the genome. The majority of the longest contigs (89 out of the top 100) are covered more than 15 times. See also Supplementary Fig. S3 for further distribution analysis.

The green area of Supplementary Fig. S3, which represents nucleotides of 10× coverage depth, covers 668 837 291 bases, accounting for 65.3% of the total contig size (1 024 053 188 bases), whereas the yellow area covers 25.3% (258 687 068 bases). It is highly likely that the green area consists of contigs with high polymorphism and the yellow area those with less polymorphism. If so, nearly two-thirds of genome sequences are highly polymorphic. As this would prevent proper contig assembly, polymorphism is probably one of the major reasons why contig N50 is small.

The size of the P. fucata genome, as estimated by flow cytometry, is 1150 Mb (Fig. 1B). On the other hand, the euchromatic region of the genome is ∼666 Mb (see Supplementary data), indicating that ∼58% of the genome is euchromatic and the other 42% heterochromatic. The euchromatic sequences occupy ∼73 and 66% of the genomes of C. intestinalis and O. latipes, respectively. Compared with these, the pearl oyster genome includes more heterochromatic regions; this may be one of the reasons why the P. fucata genome is comparatively large.

On the other hand, if the former are of less allelic polymorphism while the latter high allelic polymorphism, this result raises an intriguing possibility. As mentioned in Section 2, the pearl oyster whose genome is described in this study is from a strain that Mikimoto Co. has cultivated for more than 30 years. The strain might have been selected for better production of pearls under both qualitative and quantitative genetic pressure. If this is the case, and if genes found in the genomic area with less heterozygosity are responsible for calcification or pearl production, we may have revealed some of the reasons why this strain is advantageous for pearl production. On the other hand, polymorphic genes from the region with high heterozygosity will be useful as markers in studies of the population genetics of pearl oysters.

3.3.2. Mitochondrial genome

In contrast to the large nuclear genome, which encodes more than 20 000 protein-coding genes, the typical mitochondrial genome of metazoans is small, circular, and 15−17 kb long.55 It contains genes encoding 13 proteins of the respiratory chain [cytochorome c oxidase subunit I−III (cox1, cox2, and cox3), apocytochrome b (cytb), ATPase 6 and 8 (atp6 and atp8), and NADH dehydrogenase subunits 1–6 and 4L (nad1–6 and nad4L), two for rRNA (rrnS and rrnL), and 22 genes for tRNA (trn)].55 Although molluscs in general, and bivalves in particular, exhibit an extraordinarily high degree of mitochondrial gene order variation when compared with other clades of metazoans,56–58 it is reasonable to analyse the P. fucata mitochondrial genome to examine the degree of contig construction.

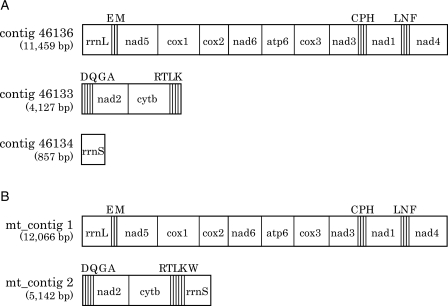

First, BLAST search, using bivalvian mitochondrial genes as queries against contigs of the P. fucata draft genome, yielded three contigs containing mitochondrial genes (Fig. 4A). The first and largest contig (no. 46136), which consisted of 11 459 bp, contained rrnL, trnE, trnM, nad5, cox1, cox2, nad6, atp6, cox3, nad3, trnC, trnP, trnH, nad1, trnL, trnN, trnF, and nad4, in that order. The second contig (no. 46133), 4127 bp in length, contained trnD, trnQ, trnG, trnA, nad2, trnR, trnT, trnL, and trnK, in that order (Fig. 4A). The third contig (no. 46134), 857 bp in length, included rrnS. This analysis did not identify atp8, trnI, trnS, trnW, trnY, or trnV. Previous studies, however, demonstrated that atp8 has been lost independently from the mitochondrial genomes of several bivalves and oysters.56–58

Figure 4.

Arrangement of P. fucata mitochondrial genes in (A) three contigs and (B) two cluster constructions of the genome.

Secondly, we reconstructed contigs that contained only mitochondrial genes, as described in Section 2. This analysis yielded two contigs, mt1 and mt2 (Fig. 4B). mt1, 12 066 bp in length, contained genes whose arrangement is identical to contig 46136 (Fig. 4B). On the other hand, mt2 (5142 bp) contained trnD, trnQ, trnG, trnA, nad2, trnR, trnT, trnL, trnK, trnW, and rrnS; in other words, contigs 46133 and 46134 were joined via trnW into a single mitochondrial contig, mt2 (compare Fig. 4A and B).

These analyses of mitochondrial genes suggest that the coverage of the pearl oyster genome sequences (both nuclear and mitochondrial DNAs) was high. The occurrence of the three contigs obtained via BLAST (no. 46136, 46133, and 46134), compared with that of two reconstructed mitochondrial contigs, suggested that the sequence assembly and contig construction themselves were not always insufficient. This also supports the notion that the low contig N50 was caused by high allelic polymorphism in pearl oyster nuclear DNA.

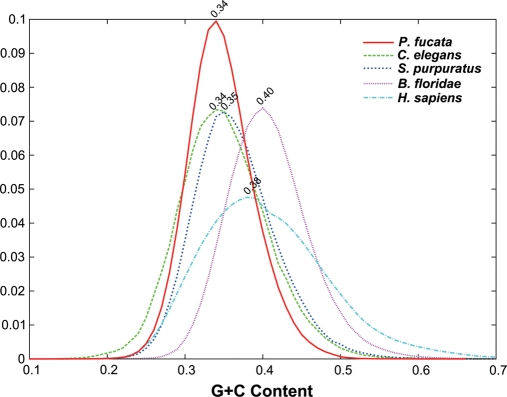

3.4. The GC content

The GC content was estimated to be ∼34% from the assembled genome sequences (Fig. 5), and therefore the pearl oyster genome is AT-rich. Figure 5 shows GC contents of genomes of various metazoans for comparison; they ranged from low values (34% in P. fucata and C. elegans; 35% in Strongylocentrotus purpuratus) to higher values (40% in H. sapiens; 38% in B. floridae) genomes. Based on these comparisons, we conclude that P. fucata has a relatively high AT-content among metazoans.

Figure 5.

The GC content of the P. fucata assembled genome (500 bp sliding window). The vertical axis shows counts of DNA sequence reads; the horizontal axis, percentage of GC in the reads. The GC content of the pearl oyster genome was estimated to be ∼34%. The GC contents of genomes of C. elegans (34%), Strongylocentrotus pulpulatus (35%), B. floridae (40%), and H. sapiens (38%) are shown for comparison.

3.5. Sequence contamination from other organisms

The present P. fucata genome project used sperm DNA from a single male. In the assembled genome, we have not detected any sequences that are predicted to correspond to bacteria or other contaminating organisms. The single peak in the GC content of the raw reads (Fig. 5) further supported lack of sequence contamination.

3.6. EST sequencing, clustering, and mapping

Transcriptome analysis is essential in order to understand the genes that are expressed in a given organism. As mentioned before, a recent EST analysis of P. fucata identified 29 682 unique sequences.7 Here, we performed EST analyses of P. fucata with the aid of a Roche 454 GS-FLX. RNA was isolated from a mixture of nine developmental stages. Sequencing yielded 36 780 contigs (29.3 Mb) over 100 bp with an N50 size of 1575 bp. Of these, 33 570 (91.3%) had a BLAT alignment to the assembled genome (using default settings). Of the 36 780 contigs, 8571 contained a complete ORF of at least 450 bp. Of these putatively full-length EST contigs, 8342 (97.3%) had a BLAT alignment to the assembled scaffolds. These data were used to produce gene models and annotation.

3.7. Gene modelling

The final set of the P. fucata gene model version 1 contained 43 760 genes (Table 2). Of them, 23 257 were complete models with the both start and stop codons (Table 2). Of these, 69.7% are substantially supported by P. fucata ESTs (Table 2).

Table 2.

The gene model of P. fucata

| Genome size (Mb) | 1150 |

| Total assembly (Mb) | 1413 |

| Number of gene models | 43 760 |

| Number of complete gene models (with start and stop codons) | 23 257 |

| Average length of transcripts (bp) | 1885 |

| Number of exons per gene | 3.2 |

| Average length of exons (bp) | 588.7 |

| Average length of genes (kb) | 6.7 |

| Average length of proteins (aa) | 274.1 |

| BLAST hit to transcriptome | 16 221/23 257 |

At the present modelling stage, the average length of genes was 7700 bp. The number of exons per gene was 3.2, and average length of exons was 589 bp, suggesting that a gene consists of 1885-bp long exons on average. Thus, each gene contains on average 4815 bp of intronic sequence (6700–1885 = 4815). The long intron insertions partially explain the large genome size of P. fucata. Proteins consisted of 274 amino acids on average.

The 43 760 predicted protein-coding loci should be examined by further improvement of sequence assembly and gene prediction. Due to the short lengths of contigs and scaffolds, presumably caused by insufficient coverage of the comparatively large genome, the model may include predictions that do not represent bona fide protein-coding genes. Such spurious predictions could arise from unrecognized repetitive elements and/or splitting of genes between scaffolds. However, BLAST search of the 23 257 predicted Pinctada genes with those of other metazoans showed that 15 077 of the Pinctada gene models (65%) are homologous to other metazoan genes or ESTs.

3.8. Genome browser

A genome browser has been established (Supplementary Fig. S4) and is available via http://marinegenomics.oist.jp/pinctada_fucata.

3.9. TEs and other genomic components

As is the case for the pearl oyster, mollusc genomes are comparatively large in size, plausibly due to the presence of a larger number of TEs and repetitive elements in the genome. Recently Yoshida et al.59 examined whether repetitive elements caused expansion of the genome size in molluscs. They showed that the proportions of repetitive elements are 9.2, 4.0, and 3.8% in the pygmy squid, nautilus, and scallop, respectively. Since their genome sizes are estimated to be 2.1, 4.2, and 1.8 Gb, respectively, the authors concluded that the repetitive element expansion does not always explain the increase in genome size; specifically, nautilus is an outlier.

We determined the proportion of TEs and repetitive elements in the assembled genome of the pearl oyster. As shown in Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table S4, 0.37 and 1.45% of the P. fucata genome appear to originate from DNA transposons and retrotransposons, respectively. The DNA transposons included Mariner, Polinton, Helitron, Academ, and others, while retrotransposons included LTR retrotransposons such as Gypsy, DIRS, and Bel_Pao as well as non-LTR retrotransposons such as enelop and CR1. The percentages of LINEs (long interspersed nuclear elements such as L1, RTE, and Jockey) and SINEs were not significantly high in the pearl oyster genome. These ratios are lower than those of three mollusc species mentioned above. On the other hand, nearly 7.9% of the genome was occupied by tandem repeat elements (Fig. 6; Supplementary Table S4); among these repeats, microsatellites occupied ∼3.7% of the genome.

Figure 6.

Repeat elements in the P. fucata genome.

It is possible that repetitive elements, especially shorter ones, were discarded during the process of sequence assembly. To examine this issue, we also determined the proportion of DNA transposons, retrotransposons, and tandem repeats in raw data generated in a one-run WGS read. We determined that the three data sets yielded similar results; one example is shown in Supplementary Table S4. The percentages of DNA transposons and retrotransposons were 0.4 and 2.7, respectively, suggesting that the assembly process did not affect so much the estimation of DNA transposons and retrotransposons in the Pinctada genome.

Although the ratio of these components is likely to be underestimated, owing to the insufficient assembly of genome sequences because of the large genome size, these data indicate that the Pinctada genome contains a comparatively small number of DNA transposons, retrotransposons, and tandem repeats. Therefore, the presence of these elements is not the cause of the large genome size.

3.10. Identification of P. fucata genes reported to be associated with shell formation

To date, cDNAs and/or proteins for more than 80 genes have been reported as those associated with the calcification and/or bivalve shell formation.6 These include Aspein,60 ferritin,61 KRMP,62 MSI60,63 N16,64 N19,65 Nacrein,66 PFMG,67 Pfty (Pictada fucata tyrosinase-1),68 Pif177,69 Prisilkin-39,70 Prismalin-14,71 and Shematrin72 (Table 3). In order to examine the validity of the assembled genome, we searched for corresponding genes in the assembled P. fucata genome. We found the presence of 21 corresponding genes in the genome (Table 3). We found four genes corresponding to N-19 in the genome, three of which are aligned in scaffold 2495, suggesting tandem duplication of the genes (data not shown).

Table 3.

The gene location in the P. fucata genome for reported cDNAs or proteins that are associated with pearl oyster shell matrix formation

| Protein | cDNA accession number | Scaffolds |

|---|---|---|

| Aspein | AB094512 | sca03_465.1 |

| Chitin synthase 1 | AB290881 | sca03_4962.1 |

| KRMP-3(MSI7) | AF516712 | sca03_229418.1 |

| MSI60 | D86074 | sca03_523.1 |

| N16 | AB023067 (#1) | sca03_1834.1 |

| N19 | AB332326 | sca03_2495.1 |

| Nacrein | D83523 | sca03_33972.1 |

| PFMG1 | DQ104255 | sca03_72180.1 |

| Pfty-1 | AB254132 | sca03_10251.1 |

| Pfty-2 | AB254133 | sca03_21093.1 |

| Pif177 | AB236929 | sca03_20175.1 |

| Prisilkin-39 | EU921665 | sca03_12887.1 |

| Prismalin-14 | AB159512 | sca03_15935.1 |

| Prismin | AB368930 | sca03_263.1 |

| Shematrin-1 | AB244419 | sca03_24266.1 |

| Shematrin-2 | AB244420 | sca03_89285.1 |

| Shematrin-3 | AB244421 | sca03_72160.1 |

| Shematrin-4 | AB244422 | sca03_16186.1 |

| Shematrin-5 | AB244423 | sca03_3950.1 |

| Shematrin-6 | AB244424 | sca03_14895.1 |

| Shematrin-7 | AB244425 | sca03_411.1 |

These results suggest that the present draft genome will be useful for exploration of the organization of various genes in the pearl oyster genome. An annotation and characterization of the pearl formation-related genes, found in previous studies, are now underway (Kinoshita et al., unpublished).

3.11. Transcription factors and signal transduction molecules

Transcription factors and signal transduction molecules play pivotal roles in the formation of animal body plans.73,74 Qualitative and quantitative changes in these molecules have been discussed in the context of the evolution of mollusc body plans.15,75 We examined transcription factors and signal transduction molecules using the Pfam domain method.

We determined the number of domains that have been identified in transcription factors and compared it with the genomes of N. vectensis, D. melanogaster, and H. sapiens (Supplementary Table S5). The domains include HLH, homeobox, nuclear hormone receptors, POU, bZIP1, Ets, Fork head, PAX, SRF-TF, GATA, HMG box, RHD, DM SRF, Runt, P53 DNA-binding domain, T-box, and others (Supplementary Table S5). This analysis illustrates several characteristic features of transcription factors in the pearl oyster genome (Supplementary Table S5). First, the genome contains major transcription factors found in other metazoan genomes. For example, in the Gene Model version 1.0, the Pinctada genome contains 43 genes for the bHLH domain, 88 genes for the homeobox domain, and 25 for nuclear hormone receptor domains. These numbers are comparable with those found in the Drosophila genome, and about half of those found in the human genome.

3.12. Signalling molecules

Recent studies of genes encoding cell−cell signalling molecules in molluscs reported unexpected complexity among the signalling genes. As in the case of identifying domains associated with transcription factors, we used the Pfam domain method to identify genes involved in cell−cell signal transduction. The results are summarized in Supplementary Table S6. The Pinctada genome contains genes that encode major signalling molecules, including members of the Wnt family, TGF-β family, and G-protein-coupled signalling family (Supplementary Table S6). For example, the Pinctada, Nematostella, and Drosophila genomes contain, respectively, 4, 6, and 8 candidates for the TGF-β family, and 9, 13, and 10 candidates for the G-protein-coupled signalling family. At present, the Pinctada genome contains six genes in the Wnt family and one gene in the FGF family (Supplementary Table S6).

Although the human genome contains genes for interleukin domains, the Nematostella and Drosophila genomes are unlikely to have genes for interleukin domains, including interleukin-2, -3, -4, -5, -7, -11, and -12 (Supplementary Table S6). The mollusc P. fucata genome also lacks interleukin genes.

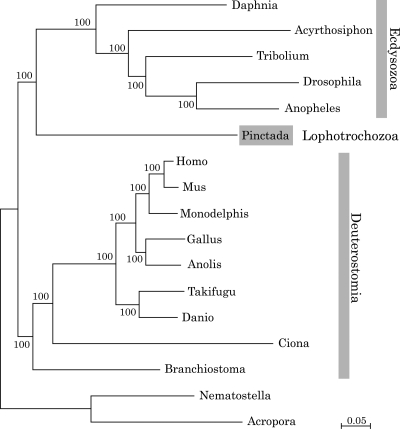

3.13. Molecular phylogeny of the molluscs

Molecular phylogeny is a powerful and objective method for inferring the phylogenic relationships of extant metazoans; various molecules have recently been used, singly or in combination, to deduce mollusc phylogeny in the context of the evolution of lophotrochozoans. For example, Dunn et al.11 examined the broad phylogenic relationship among animals, using data from 77 taxa and 150 genes. This study positioned Mollusca in a clade of Lophotrochozoa, together with another group that includes Annelida, Phoronidae, Nemertea, and Entoprocta. On the other hand, Paps et al.76 reported that Mollusca forms a clade with Brachiozoa as a group of Spiralia within Lophotrochozoa.

Within the 2087 orthologus genes, 409 genes were detected in all selected organisms, which allowed us to compare 77 547 aligned amino acid positions (see Section 2). As shown in Fig. 7, the tree indicates that the mollusc forms a clade of Lophotrochozoa that is independent from a clade comprising ecdysozoans and deuterostomes. This is the first confirmation by genome-wide analyses using nuclear genes of the three major groups of bilaterians.

Figure 7.

Molecular phylogeny of the pearl oyster. A total of 77 547 aligned amino acid positions of proteins encoded by 409 genes were obtained from the triploblasts T. castaneum, D. melanogaster, A. gambiae, A. pisum, P. fucata, B. floridae, C. intestinalis, D. rerio, T. rubripes, M. domestica, G. gallus, A. carolinensis, M. musculus, and H. sapiens. The sequences were analysed using ML methods, with the diploblasts A. digitifera and N. vectensis serving as an outgroup. The scale bar represents 0.05 expected substitutions per site in the aligned regions. The topology was supported by 100% bootstrap value. This analysis shows the phylogenic position of molluscs obtained using genome-wide data from all of these species.

3.14. Conclusion

We sequenced the genome of the pearl oyster P. fucata using pyrosequencing technologies. The draft genome, ∼1150 Mb at this draft stage, contains 23 257 complete gene models. Most likely, the assembled genome contains almost no sequences derived from other organisms such as bacteria, because the genome DNA was obtained from the sperm of a single male. In spite of the recent accumulation of genomic information in various metazoan taxa, there have been very few reports of sequenced genomes of molluscs and/or lophotrochozoans. This study therefore provides the first opportunity to obtain insight into a bivalvian mollusc genome. The P. fucata genome also provides a basic platform for further studies of the biosynthesis of pearl, which has a significant importance in the fisheries industry. Such studies are now in progress by multiple investigators, including the authors of this study.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data are available online at www.dnaresearch.oxfordjournal.org.

Funding

This work was supported by the OIST Internal Fund for Marine Genomics Unit. We thank S. Brenner and R. Baughman for their support. The supercomputer work was supported by the IT Section of the OIST and the Human Genome Center at the University of Tokyo.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Weiss I.M., Tuross N., Addadi L., Weiner S. Mollusc larval shell formation: amorphous calcium carbonate is a precursor phase for aragonite. J. Exp. Zool. 2002;293:478–91. doi: 10.1002/jez.90004. doi:10.1002/jez.90004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Addadi L., Raz S., Weiner S. Taking advantage of disorder: amorphous calcium carbonate and its roles in biomineralization. Adv. Mater. 2003;15:959–70. doi:10.1002/adma.200300381. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerhke N., Nassif N., Pinna N., Antonetti M., Gupta H.S. Retrosynthesis of nacre via amorphous precursor particles. Chem. Mater. 2005;17:6514–6. doi:10.1021/cm052150k. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marin F., Luquet G., Marie B., Medakovic D. Molluscan shell proteins: primary structure, origin, and evolution. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2008;80:209–76. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(07)80006-8. doi:10.1016/S0070-2153(07)80006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sarashina I., Endo K. Skeletal matrix proteins of invertebrate animals: comparative analysis of their amino acid sequences. Paleontol. Res. 2006;10:311–36. doi:10.2517/prpsj.10.311. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joubert C., Piquemal D., Marie B., et al. Transcriptome and proteome analysis of Pinctada margaritifera calcifying mantle and shell: focus on biomineralization. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:613. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-613. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-11-613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kinoshita S., Wang N., Inoue H., et al. Deep sequencing of ESTs from nacreous and prismatic layer producing tissues and a screen for novel shell formation-related genes in the Pearl Oyster. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21238. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nielsen C. Animal Evolution. Interrelationships of the Living Phyla. 2nd edn. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brusca R.C., Brusca G.J. Invertebrates. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates Inc.; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruppert E.E., Fox R.S., Barnes R.D. Invertebrate Zoology. Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunn C.W., Hejnol A., Matus D.Q., et al. Broad phylogenomic sampling improves resolution of the animal tree of life. Nature. 2008;452:745–9. doi: 10.1038/nature06614. doi:10.1038/nature06614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pojeta J. The origin and early taxonomic diversification of pelecypods. Philos. Trans. Roy. Soc. Lond. Ser. B. 1978;284:225–46. doi:10.1098/rstb.1978.0065. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clarkson E.N.K. Invertebrate Palaeontology and Evolution. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Science Ltd; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kocot K.M., Cannon J.T., Todt C., et al. Phylogenomics reveals deep molluscan relationships. Nature. 2011;477:452–6. doi: 10.1038/nature10382. doi:10.1038/nature10382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kin K., Kakoi S., Wada H. A novel role for dpp in the shaping of bivalve shells revealed in a conserved molluscan developmental program. Dev. Biol. 2009;329:152–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.01.021. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.C. elegans Sequencing Consortium. Genome sequence of the nematode C. elegans: a platform for investigating biology. Science. 1998;282:2012–8. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2012. doi:10.1126/science.282.5396.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.I.H.G.S Consortium. Finishing the euchromatic sequence of the human genome. Nature. 2004;431:931–45. doi: 10.1038/nature03001. doi:10.1038/nature03001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aparicio S., Chapman J., Stupka E., et al. Whole-genome shotgun assembly and analysis of the genome of Fugu rubripes. Science. 2002;297:1301–10. doi: 10.1126/science.1072104. doi:10.1126/science.1072104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Consortium M.G.S. Initial sequencing and comparative analysis of the mouse genome. Nature. 2002;420:520–62. doi: 10.1038/nature01262. doi:10.1038/nature01262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dehal P., Satou Y., Campbell R.K., et al. The draft genome of Ciona intestinalis: insights into chordate and vertebrate origins. Science. 2002;298:2157–67. doi: 10.1126/science.1080049. doi:10.1126/science.1080049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Putnam N.H., Butts T., Ferrier D.E., et al. The amphioxus genome and the evolution of the chordate karyotype. Nature. 2008;453:1064–71. doi: 10.1038/nature06967. doi:10.1038/nature06967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adams M.D., Celniker S.E., Holt R.A., et al. The genome sequence of Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 2000;287:2185–95. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2185. doi:10.1126/science.287.5461.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.H.G.S. Consortium. Insights into social insects from the genome of the honeybee Apis mellifera. Nature. 2006;443:931–49. doi: 10.1038/nature05260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Putnam N.H., Srivastava M., Hellsten U., et al. Sea anemone genome reveals ancestral eumetazoan gene repertoire and genomic organization. Science. 2007;317:86–94. doi: 10.1126/science.1139158. doi:10.1126/science.1139158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chapman J.A., Kirkness E.F., Simakov O., et al. The dynamic genome of Hydra. Nature. 2010;464:592–6. doi: 10.1038/nature08830. doi:10.1038/nature08830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shinzato C., Shoguchi E., Kawashima T., et al. Using the Acropora digitifera genome to understand coral responses to environmental change. Nature. 2011;476:320–323. doi: 10.1038/nature10249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Srivastava M., Begovic E., Chapman J., et al. The Trichoplax genome and the nature of placozoans. Nature. 2008;454:955–60. doi: 10.1038/nature07191. doi:10.1038/nature07191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Srivastava M., Simakov O., Chapman J., et al. The Amphimedon queenslandica genome and the evolution of animal complexity. Nature. 2010;466:720–6. doi: 10.1038/nature09201. doi:10.1038/nature09201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shoguchi E., Kawashima T., Nishida-Umehara C., Matsuda Y., Satoh N. Molecular cytogenetic characterization of Ciona intestinalis chromosomes. Zoolog. Sci. 2005;22:511–6. doi: 10.2108/zsj.22.511. doi:10.2108/zsj.22.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davies D.C., Allen P. DNA analysis by flow cytometry. In: Macey M.G., editor. Flow Cytometry: Principles and Applications. Totowa, NJ, USA: Humana Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kasahara M., Naruse K., Sasaki S., et al. The medaka draft genome and insights into vertebrate genome evolution. Nature. 2007;447:714–9. doi: 10.1038/nature05846. doi:10.1038/nature05846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ciudad J., Velasco A., Lara J.M., et al. Flow cytometry measurement of the DNA contents of G0/G1 diploid cells from three different teleost fish species. Cytometry. 2002;48:20–5. doi: 10.1002/cyto.10100. doi:10.1002/cyto.10100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Margulies M., Egholm M., Altman W.E., et al. Genome sequencing in microfabricated high-density picolitre reactors. Nature. 2005;437:376–80. doi: 10.1038/nature03959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bentley D.R. Whole-genome re-sequencing. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2006;16:545–52. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.10.009. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boetzer M., Henkel C.V., Jansen H.J., et al. Scaffolding pre-assembled contigs using SSPACE. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:578–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq683. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btq683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stanke M., Diekhans M., Baertsch R., Haussler D. Using native and syntenically mapped cDNA alignments to improve de novo gene finding. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:637–44. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn013. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btn013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haas B.J., Delcher A.L., Mount S.M., et al. Improving the Arabidopsis genome annotation using maximal transcript alignment assemblies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:5654–66. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg770. doi:10.1093/nar/gkg770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smit A.F.A., Hubley R., Green P. 1996–2010. RepeatMasker Open-3.0.

- 39.Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:573–80. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sobreira T.J., Durham A.M., Gruber A. TRAP: automated classification, quantification and annotation of tandemly repeated sequences. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:361–2. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Price A.L., Jones N.C., Pevzner P.A. De novo identification of repeat families in large genomes. Proceedings of the 13 Annual International Conference on Intelligent Systems for Molecular Biology (ISMB-05); Detroit, MI. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jurka J., Kapitonov V.V., Pavlicek A., Klonowski P., Kohany O., Walichiewicz J. Repbase Update, a database of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Cytogen. Genome Res. 2005;110:462–7. doi: 10.1159/000084979. doi:10.1159/000084979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jurka J., Klonowski P., Dagman V., Pelton P. CENSOR—a program for identification and elimination of repetitive elements from DNA sequences. Computers Chem. 1996;20:119–22. doi: 10.1016/s0097-8485(96)80013-1. doi:10.1016/S0097-8485(96)80013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Finn R.D., Mistry J., Schuster-Bockler B., et al. Pfam: clans, web tools and services. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D247–51. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj149. doi:10.1093/nar/gkj149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eddy S.R. Profile hidden Markov models. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:755–63. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.755. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stein L.D., Mungall C., Shu S., et al. The generic genome browser: a building block for a model organism system database. Genome Res. 2002;12:1599–610. doi: 10.1101/gr.403602. doi:10.1101/gr.403602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wyman S.K., Jansen R.K., Boore J.L. Automatic annotation of organellar genomes with DOGMA. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3252–5. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth352. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bth352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Laslett D., Canbäck B. ARWEN, a program to detect tRNA genes in metazoan mitochondrial nucleotide sequences , Bioinformatics. 2008;24:172–5. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm573. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btm573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lowe T.M., Eddy S.R. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:955–64. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.955. doi:10.1093/nar/25.5.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Philippe H., Lartillot N., Brinkmann H. Multigene analyses of bilaterian animals corroborate the monophyly of Ecdysozoa, Lophotrochozoa, and Protostomia. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2005;22:1246–53. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi111. doi:10.1093/molbev/msi111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Larkin M.A., Blackshields G., Brown N.P., et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Castresana J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2000;17:540–52. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stamatakis A. RaxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2688–90. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wada K. Number and gross morphology of chromosomes in the peal oyster, Pinctada fucata (GOULD), collected from two regions of Japan. Jap. J. Malac. 1976;35:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wolstenholme D.R. Animal mitochondrial DNA: structure and evolution. Intern. Rev. Cytol. 1992;141:173–216. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)62066-5. doi:10.1016/S0074-7696(08)62066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dreyer H., Steiner G. The complete sequence and gene organization of the mitochondrial genome of the gadilid scaphopod Siphonodentalium lobatum (Mollusca) Mol. Phylog. Evol. 2003;31:605–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2003.08.007. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Doucet-Beaupré H., Breton S., Chapman E.G., et al. Mitochondrial phylogenomics of the bivalvia (Mollusca): searching for the origin and mitogenomics correlates of doubly uniparental inheritance of mtDNA. BMC Evol. Biol. 2010;10:50. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-10-50. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-10-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Serb J.M., Lydeard C. Complete mtDNA sequence of the North American freshwater mussel Lampsilis orenata (Unionidae); an examination of the evolution and phylogenetic utility of mitochondrial genome organization in bivalvia (Mollusca) Mol. Biol. Evol. 2003;20:1854–66. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg218. doi:10.1093/molbev/msg218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yoshida M.A., Ishikura Y., Moritaki T., et al. Genome structure analysis of molluscs revealed whole genome duplication and lineage specific repeat variation. Gene. 2011;483:63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2011.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tsukamoto D., Sarashina I., Endo K. Structure and expression of an unusually acidic matrix protein of pearl oyster shells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;320:1175–80. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.06.072. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.06.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang Y., Meng Q., Jiang T., Wang H., Xie L., Zhang R. A novel ferritin subunit involved in shell formation from the pearl oyster (Pinctada fucata) Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2003;135:43–54. doi: 10.1016/s1096-4959(03)00050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang C., Xie L., Huang J., Liu X., Zhang R. A novel matrix protein family participating in the prismatic layer framework formation of pearl oyster, Pinctada fucata. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;344:735–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.179. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sudo S., Fujikawa T., Nagakura T., et al. Structures of mollusc shell framework proteins. Nature. 1997;387:563–4. doi: 10.1038/42391. doi:10.1038/42391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Samata T., Hayashi N., Kono M., Hasegawa K., Horita C., Akera S. A new matrix protein family related to the nacreous layer formation of Pinctada fucata. FEBS Lett. 1999;462:225–9. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01387-3. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(99)01387-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yano M., Nagai K., Morimoto K., Miyamoto H. A novel nacre protein N19 in the pearl oyster Pinctada fucata. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;362:158–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.07.172. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.07.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Miyamoto H., Miyashita T., Okushima M., Nakano S., Morita T., Matsushiro A. A carbonic anhydrase from the nacreous layer in oyster pearls. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:9657–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9657. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.18.9657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu H.L., Liu S.F., Ge Y.J., et al. Identification and characterization of a biomineralization related gene PFMG1 highly expressed in the mantle of Pinctada fucata. Biochemistry. 2007;46:844–51. doi: 10.1021/bi061881a. doi:10.1021/bi061881a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nagai K., Yano M., Morimoto K., Miyamoto H. Tyrosinase localization in mollusc shells. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2007;146:207–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2006.10.105. doi:10.1016/j.cbpb.2006.10.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Suzuki M., Saruwatari K., Kogure T., et al. An acidic matrix protein, Pif, is a key macromolecule for nacre formation. Science. 2009;325:1388–90. doi: 10.1126/science.1173793. doi:10.1126/science.1173793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kong Y., Jing G., Yan Z., et al. Cloning and characterization of Prisilkin-39, a novel matrix protein serving a dual role in the prismatic layer formation from the oyster. Pinctada fucata. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:10841–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808357200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M808357200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Suzuki M., Murayama E., Inoue H., et al. Characterization of Prismalin-14, a novel matrix protein from the prismatic layer of the Japanese pearl oyster (Pinctada fucata) Biochem. J. 2004;382:205–13. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040319. doi:10.1042/BJ20040319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yano M., Nagai K., Morimoto K., Miyamoto H. Shematrin: a family of glycine-rich structural proteins in the shell of the pearl oyster Pinctada fucata. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2006;144:254–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2006.03.004. doi:10.1016/j.cbpb.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Carrol S.B., Grenier J.K., Weatherbee S.D. Molecular Genetics and the Evolution of Animal Design. 2nd edn. Malden, MA, USA: Blackwell Pub; 2005. From DNA to diversity. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Davidson E.H. The Regulatory Genome. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nederbragt A.J., van Loon A.E., Dictus W.J. Expression of Patella vulgata orthologs of engrailed and dpp-BMP2/4 in adjacent domains during molluscan shell development suggests a conserved compartment boundary mechanism. Dev. Biol. 2002;246:341–55. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0653. doi:10.1006/dbio.2002.0653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Paps J., Baguna J., Riutort M. Bilaterian phylogeny: a broad sampling of 13 nuclear genes provides a new Lophotrochozoa phylogeny and supports a paraphyletic basal acoelomorpha. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2009;26:2397–406. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp150. doi:10.1093/molbev/msp150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.