Abstract

In this study, we explored how adolescents in rural Kenya apply religious coping in sexual decision-making in the context of high rates of poverty and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 34 adolescents. One-third (13) reported religious coping related to economic stress, HIV, or sexual decision-making; the majority (29) reported religious coping with these or other stressors. Adolescents reported praying for God to partner with them to engage in positive behaviors, praying for strength to resist unwanted behaviors, and passive strategies characterized by waiting for God to provide resources or protection from HIV. Adolescents in Sub-Saharan Africa may benefit from HIV prevention interventions that integrate and build upon their use of religious coping.

Keywords: Adolescents, Religious Coping, Poverty, Religion, Sexual Risk Behavior, HIV Prevention, Africa, Kenya

Understanding adolescents’ sexual decision making is crucial for preventing sexually transmitted illnesses, including Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). Thus far, HIV prevention efforts have shown limited success in reducing sexual risk behavior (Diclemente, 2008; Gallant & Maticka-Tyndale, 2004). This has pointed to the need for culturally tailored interventions (Noar, 2008) that target context-specific factors beyond HIV-related knowledge (Coates, Richter, & Caceres, 2008). Cultural tailoring is particularly important in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), home to 68% of the world's HIV-infected population and where many are infected between ages 15 and 24 (Allison & Seeley, 2004; UNAIDS, 2008). In Nyanza Province, Kenya, where this study was conducted, HIV prevalence is 15.3%, the highest in the country (UNAIDS, 2008). Religiosity is one cultural factor that has received little attention in the literature, but that could influence sexual behavior in SSA. In this study, we examine religiosity in relation to adolescents’ sexual decision-making and poverty in Kenya.

Religiosity, defined as participation in organized religious activities, rituals and practices (Miller & Thoresen, 1999), is one factor that has been associated with lower levels of sexual risk behavior among African youth (Kiragu & Zabin, 1993). In Kenya, 80% of individuals self-identify as Christian (Bureau of Democracy Human Rights and Labor, 2009), and churches are influential social and cultural institutions (Kaplan, 1986). Religious belief systems offer principles related to coping with stressors of poverty (Johnson, 2007), and tenets related to decisions about relationships and sexual behavior, sometimes in contradiction to traditional customs related to sexuality (see Maticka-Tyndale et al., 2005). Despite the cultural centrality of religion and initial findings that religiosity may be protective in HIV acquisition, to our knowledge the association between religiosity and HIV risk behaviors has not been examined among adolescents in SSA, particularly in the context of high levels of economic stress.

Poverty and Sexual Behavior

Access to resources influences sexual decision-making, particularly in fishing communities like Nyanza where transactional sex is well-documented (Béné & Merten, 2008). In this setting, females trade sex to obtain fish to eat and sell, and sex is often part of solidifying these business relationships (Ayikukwei et al., 2008; Maticka-Tyndale, et al., 2005). This takes place in a context of gender inequality, where males own and control most money and property (Ellis, 2007) and traditions of early marriage and polygyny create norms in which females are expected to agree to sexual relationships (Maticka-Tyndale, et al.). Females rarely earn enough money independently, and transactional sex is one of few options for acquiring money or goods (Ellis). Therefore, while high HIV prevalence cannot be attributed to poverty alone (Gillespie, Greener, Whiteside, & Whitworth, 2007), unequal access to resources is one reason that poverty is a barrier to the efficacy of prevention efforts in SSA (Parker, Easton, & Klein, 2000).

Religiosity, Coping, and Sexual Decision-Making

Religiosity may influence how adolescents cope with the stressors of poverty and make decisions about sex. Religiosity has been associated with delayed sexual debut, especially among females, in the U.S. (Rostosky, Wilcox, Wright, & Randall, 2004) and Kenya (Kiragu & Zabin, 1993). Religion also may influence how adolescents think about and cope with poverty, as most spiritual belief systems, including African traditional religions, promote trusting God for material needs and providing for the poor (Amoah, 2009).

Religious coping is a specific dimension of religiosity that could explain associations of religiosity with lower HIV risk behavior. Religious coping is “how the individual [makes] use of religion to understand and deal with stressors” in either positive or negative ways (K. I. Pargament, Koenig, & Perez, 2000; p. 521). Positive religious coping is characterized by belief in a loving God or higher power that offers support and help, as well as a theological framework that helps make meaning out of suffering. In contrast, negative religious coping is characterized by feelings of abandonment by God or higher power and religious turmoil. Positive religious coping has been associated with multiple beneficial health outcomes (for review, see George, Ellison, & Larson, 2002), whereas negative religious coping has been related to increased depression and anxiety (Koenig et al., 1992; K. I. Pargament, 1997).

Studies have not yet examined associations between religious coping and sexual behavior. However, because religious beliefs often provide moral frameworks on sexuality and tenets related to poverty, it follows that adolescents may use religious coping when facing stressors related to poverty and sex. This is particularly interesting in Nyanza, as Christianity in particular promotes monogamy and abstinence until marriage, in stark contrast to customs of polygyny, wife inheritance, and early sexual activity that may perpetuate high rates of HIV in this region (Maticka-Tyndale, et al., 2005; Oluga, Kiragu, Mohamed, & Walli, 2010).

In this study, we examined whether and how adolescents used religious coping to respond to stress related to poverty and decisions about sex, as sexual behavior has implications for both access to resources and risk of contracting HIV. We aimed to explore how adolescents in rural Kenya applied positive or religious coping in sexual decision-making in the context of high rates of poverty and HIV and the ways in which religious coping may influence adolescents’ stress levels and engagement in risk behavior.

Setting

This study was conducted in Muhuru, a division of Nyanza on Lake Victoria with a population of 25,000. Fishing is the primary economic activity, and lack of other opportunities contributes to high poverty. Few students in this setting are able to pursue education beyond the primary level, as most students do not have qualifying scores or funds for secondary school. For females, early marriage and pregnancy are additional barriers to education and economic opportunity (Ikamari, 2008). Most inhabitants belong to the Luo or Suba tribes, which both have strict gender roles. Women carry domestic responsibilities and often contribute to household income, but men control all property and resources (Francis, 1995). Polygyny and wife inheritance (i.e., widows inherited by the late husband's brother), are also traditions that continue to limit women's power in sexual decision making and may increase HIV transmission (Luginaah, Elkins, Maticka-Tyndale, Landry, & Mathui, 2005). Muhuru has 56 churches, and the majority of people self-identify as Christian. Common denominations are Catholic, Seventh Day Adventist, and Pentecostal. Churches are major social gathering places, and church leaders are regarded as important role models.

Method

Data were collected as part of a mixed-methods study on HIV risk among adolescents. In-depth interviews were conducted to understand the social context of behavior, explore topics from the participants’ perspectives, and uncover issues not preconceived by the researchers (Creswell, 2009). Students ages 10 to 19 in school levels 5 to 8 were eligible, and an equal number of males and females were selected randomly from school rosters. Of 38 adolescents identified, 34 enrolled (89.5%); 1 declined, and 3 could not be located or scheduled. The final sample included 16 males and 18 females with a mean age of 14 years. Thirty-three self-identified as Christian and one as Muslim; his responses did not differ from the rest of the sample in any notable way. All reported attending church or mosque regularly.

After obtaining parental permission and adolescent assent, interviewers used a semi-structured guide with broad questions and probes on sexual behavior, beliefs about sex and HIV, emotional health and coping strategies. Questions were based on ecological systems theory, asking about individual-level processes and family- and community-level support. Examples of questions included: (a) “Tell me about a recent problem you have faced.... Describe how you handled this,” (b) “Tell me about your faith...Tell me about God - what He is like and what He does,” and (c) “Do you attend church?...Tell me what you do there and what it is like.”

Interviews lasted approximately 90 minutes, were audio recorded, transcribed in Dholuo, and translated into English. Data were analyzed with QSR International NVivo 8. To develop the coding scheme, the first two authors reviewed the transcripts to identify important emerging topics and themes. The first eight transcripts were coded by both authors and discussed to establish reliability and consistency. Content used for analysis included participants’ statements related to religion, coping, economic resources, and HIV and sex; queries were used to analyze portions of transcripts in which adolescents discussed combinations of these themes. Authors discussed data to identify specific themes that emerged related to the research questions.

Results

The majority of adolescents (n = 29; 85.3%) described using religious coping as part of a coping response to some type of recent stressor. Religious coping across all stressors was common across both genders, but reported by a larger percentage of females than males (94% vs. 75%). The broad range of stressors that prompted the use of religious coping included: poverty, illness or fear of illness (including HIV), bereavement, worry about the future, academic performance, and moral struggles with decision-making (e.g., sexual behavior, stealing). Within the 29 participants reporting using religious coping, 13 used religious coping to deal specifically with economic stress, HIV risk, or sexual decision-making – the stressors on which we focus in this analysis.

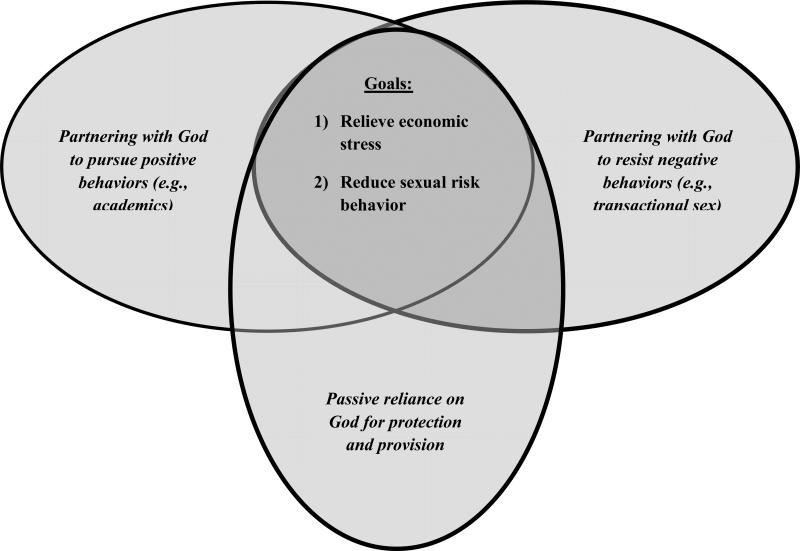

Personal prayer was the most commonly reported religious coping behavior, and youth did not often describe receiving material or social support from the church or church members. Additionally, while some adolescents said that they felt comfortable talking with church members about problems, none reported conversations with church leaders or members about economics, sexual decision-making, or HIV. Three main themes emerged that characterized ways in which adolescents applied religious coping (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Religious coping strategies adolescents used to relieve economic stress and to reduce risks of sexual behavior

Partnering with God to pursue positive behavior

Four participants described asking God for the capacity to engage in positive behaviors that would lead to eventual economic gain. They indicated a willingness to work hard towards their educational and financial goals, but asked for God's help for certain steps in the process, as this youth implies:

I pray that I will successfully attend school so that I get a job just like other people...I prayed to God to help me perform better this term compared to last term. (Male, Age 12)

Two adolescents, both females, reported asking God to help them choose positive behaviors to avoid risky sexual encounters, such as choosing non-sexually active peer groups.

When mum was telling me not to have sex, she told me having sex may give me HIV...I don’t want to have sex, and I am planning to walk with my friends who are not talking about sex so I am not tempted. I pray I will walk with [friends] so that I am not raped the way the boy wanted to rape me. (Female, Age 10)

This youth prayed both to cope with a past stressor (i.e., attempted rape) and to prevent future pressures to have sex. She implies perceived control over “planning” to affiliate with a certain peer group, but also implies unforeseeable barriers to implementing action. Adolescents’ recognition that they cannot always have complete control over situations may be one motivator for using prayer in combination with one's own planning and action.

Partnering with God to resist negative behavior

In addition to praying for help to engage in positive behaviors, two males and two females prayed to ask God for strength to resist negative behaviors, including stealing and transactional sex, when under economic stress. They seemed to conceptualize these behaviors as immoral, referring to them as “sins,” but noted that economic need was the primary motivator rather than immoral desires or intentions, as this student implied:

When I pray, I ask God to give me life, understanding for schoolwork, and I also ask him to forgive my sins that I have committed. I just asked [God] for life and understanding. I also prayed about how I can get the basic needs so that I may stop having sexual relationships. (Female, Age 14)

Through their prayers, adolescents described the process of reminding themselves that God can help them avoid negative behavior in multiple ways, both by providing them with the internal strength to resist temptation and by meeting material needs through alternate means. The following youth described the process of replacing the negative intent to steal with specific prayer-focused cognitions. He asks God for assistance and reminds himself about God's assistance in the past to resist stealing or sexual activity, behaviors that he clearly finds tempting.

Sometimes you think of stealing [because] lacking things is what makes someone think the worst [stealing]. What runs in my mind now is to pray to God to also give us something...God has cared for me well, kept my heart and mind away from sexual activities. God is good and caring because under His watch, I haven’t indulged in sex. He has kept me safe. I pray to God to keep my heart away from the desires of the flesh, sex, or taking other people's properties. (Male, Age 14)

Passive reliance on God for protection and provision

While the first two themes highlighted adolescents partnering with God, six participants reported asking God for protection or provision without mentioning action they would take to participate in achieving positive outcomes. They described praying for God to protect them from hardship or disease, including HIV, and to provide for their material needs. An 11-year-old female said “I pray for God not to give me HIV,” implying fear that God could take action to “give” her HIV. In many of the responses indicative of this passive approach to coping, participants suggested that their complete dependence on God was due to their perception that there were no other options for action on their part, as this youth described:

Some of the things I worry about are how I can get my school supplies and how I can get my food since my aunt is old and I have nobody [else] to assist me. If there isn’t food, I do take it easy and say, ‘God knows.’ (Male, Age 14)

Some adolescents described using a combination of active and passive coping approaches. The marrying of active and passive coping strategies is captured in this adolescent's description of how she dealt with her father's death:

My father died...I thought that I would not lead a good life since the father was breadwinner and my mother was left alone...I always pray and sleep so that I forget about that. God provides me with life and my daily bread...I always ask God to provide me with life and to be with me till I finish my school and always ask him to prepare me for his kingdom and one day live with him in heaven. (Female, Age 14)

This youth described a passive approach to prayer related to worrying about her family's future. However, she also mentioned praying for God to “be with” her as she finishes school, implying action on her part. Some adolescents may use a passive coping approach for stressors that seem overwhelming and uncontrollable, but more active approaches for challenges within their control, such as achievement in school.

Discussion

Religious coping emerged as a common way that adolescents in Muhuru coped with a broad range of stressors, and one-third of the sample used religious coping specifically to cope with economic stress, HIV risk, and sexual decision-making. Some adolescents used religious coping to buffer the effect of economic stress on sexual risk behavior that can lead to HIV. Most participants reported benevolent feelings towards God and belief and trust in God's power to help and protect them. Further, some reported partnering with God to pursue positive behaviors and resist negative behavior when they were experiencing financial stress or pressure to engage in risky sex. A few adolescents reported passive dependence on God for protection from HIV and financial support. Results suggest that faith plays a role in the ways that some adolescents are processing and responding to stressors that might lead to HIV risk.

The first two themes identified in the data clearly reflect positive religious coping as described by Pargament (1997). Adolescents talked about partnering with God to engage in positive behavior and resist negative behavior. Prayers contributed to their ability and motivation to make decisions that protected their health. Pargament (1998) refers to this as collaborative religious coping. The third theme identified reflected a more passive reliance on God. Adolescents who used this strategy reported positive appraisals of their relationships with God, but also expressed a sense of powerlessness, and sometimes fatalism, more often associated with negative religious coping. It is possible that for these adolescents, their trust in God is great, while their own sense of self-efficacy may be low, creating a perception that they must leave their fate entirely in the hands of God.

One explanation for differences in adolescents’ use of active versus passive religious coping could be the extent to which adolescents believe they have control over situations and their future. In their coping model, Lazarus and Folkman (Folkman, 1991) emphasize the importance of appraising stressors as changeable or unchangeable and using that to inform one's choice of coping strategies. They recommend problem-focused, action-oriented strategies for changeable stressors and emotion-focused strategies (e.g., distraction) for unchangeable stressors. Taking this theoretical perspective, it seems that participants differed in their appraisal of stressors related to economic resources, HIV risk, and sexual decision-making. This may be related to either adolescents’ specific circumstances or their abilities to evaluate and problem-solve around stressors. In either case, religious coping seemed to facilitate problem-focused coping for some youths (e.g., perceiving God's help as they resisted sex) and emotion-focused coping for others (e.g., reducing distress by accepting poverty and finding comfort from God's love). This is consistent with other research in Nyanza Province that reported orphans using both problem- and emotion-focused coping strategies (Herbst et al., 2007).

Across religious coping strategies, participants used prayer as their primary religious coping behavior. This was somewhat surprising, as we expected adolescents to mention more varied behaviors, including both private and social religious coping behaviors (e.g., distraction through church activities, support from church members). The distinction drawn in religiosity literature between intrinsic and extrinsic religiosity (Allport & Ross, 1967) is relevant in that data suggested more intrinsic religiosity, namely the individual-level beliefs and emotions associated with one's faith (e.g., closeness to God, private reflection, prayer). Adolescents did not discuss elements of extrinsic religiosity, including social and institutional practices associated with faith. Many reported that they enjoyed church but did not describe engaging in church-related activities to cope or forming close relationships with church members or leaders to receive support. This pattern supports findings in Tanzania that HIV-infected adults used prayer and faith to deal with their HIV diagnosis, but received little direct support from their churches (Watt, Maman, Jacobson, Laiser, & John, 2009).

Results have potential implications for HIV prevention efforts among adolescents in rural African communities such as Muhuru, suggesting that interventions may be able to build upon religious coping strategies that some adolescents are using already. . Integrating religious faith into interventions in these contexts could increase their cultural relevance and may improve participation and behavior change by building on concepts familiar to the target population, rather than introducing a new set of terms and skills not grounded in the population's beliefs and values. Interventions that are built on coping theory, such as the Lazarus and Folkman model described above (Folkman, 1991), may provide a useful framework to improve adolescents’ ability to appraise stressors and apply appropriate religious coping strategies,- in particular to decrease sole reliance on passive religious coping.. Multi-level interventions to increase church members’ and leaders’ skills to support youth are also worth considering. (Béné & Merten, 2008; Maticka-Tyndale et al., 2005b)

Study limitations preclude our ability to generalize these recommendations without further research. The breadth of interview topics limited the depth of information on religious beliefs and coping. While not asking specific questions about religious coping allowed us to observe that participants spontaneously described using religious coping, interviewers did not always gather more detail. The small sample and broad age range of participants also limited our ability to examine religious coping during specific developmental stages. Also, as in all qualitative studies, results are not designed to be generalizable.

Future studies should include more in-depth interviews and larger samples across different communities. In addition, studies should focus on whether and how religiosity and religious coping should be integrated into theories of decision-making and behavior change that often guide interventions. For instance, it is possible that religious coping should be considered as a protective factor in theoretical models based on risk and resilience (Compas, Hinden, Gerhardt, 1995) and that we should emphasize religious meso-systems in ecological systems approaches to HIV prevention in some contexts (DiClemente, Salazar, & Crosby, 2007). Larger sample studies will allow us to evaluate empirically the potential contribution of religious coping to theoretical models and interventions as they are applied to diverse contexts.

In summary, results provide evidence that religious coping may play a role in how some adolescents in SSA respond to poverty and decisions about sexual behavior. Adolescents in this rural community reported praying for God to partner with them in avoiding risk behavior, to meet their economic needs, and to protect their health. In this way, religious coping seemed protective. Given these findings from one community, further investigation is needed to evaluate the use of religious coping among adolescents in other contexts.

Acknowledgements

This project was funded in part by the Duke Global Health Institute, Johnson & Johnson Corporation, Duke University Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH funded program (P30 AI 64518), and the Fogarty Center through the International Clinical Research fellowship (first author). The authors would like to thank the team of research assistants who translated and administered the interviews in this study and the adolescents who participated. We also acknowledge the Women's Institute for Secondary Education and Research (WISER) for serving as the host non-governmental organization for this study and the Africa Mental Health Foundation (AMHF) for providing administrative support.

Contributor Information

Eve S. Puffer, International Rescue Committee 422 East 42nd Street, 12th floor New York, NY 10009.

Melissa H. Watt, Duke Global Health Institute Box 90519 Durham, North Carolina 27708 Durham, NC.

Kathleen J. Sikkema, Duke University Psychology and Neuroscience Durham, NC 27708.

Rose A. Ogwang-Odhiambo, P.O Box 536 Egerton 20115 Institute of Women, Gender, and Development Studies Njoro, Kenya

Sherryl A. Broverman, Duke Global Health Institute Box 90519 Durham, North Carolina 27708.

References

- Allison EH, Seeley JA. HIV and AIDS among fisherfolk: a threat to 'responsible fisheries'? Fish and Fisheries. 2004;5:215–234. [Google Scholar]

- Allport GW, Ross MJ. Personal religious orientation and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1967;5(4):432–443. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.5.4.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amoah E. Religion and poverty: Pan-African perspectives. Duke University Press; Durham, NC: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ayikukwei R, Nugare D, Sidle J, Ayuku D, Baliddawa J, Greene J. HIV/AIDS and cultural practices in western Kenya: the impact of sexual cleansing rituals on sexual behaviours. Culture, Health and Sexuality. 2008;10(6):587–599. doi: 10.1080/13691050802012601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Béné C, Merten S. Women and fish-for-sex: Transactional sex, HIV/AIDS and gender in African fisheries. World Development. 2008;36(5):875–899. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Democracy Human Rights and Labor International Religious Freedom Report. 2009.

- Coates TJ, Richter L, Caceres C. Behavioural strategies to reduce HIV transmission: how to make them work better. Lancet. 2008;372(9639):669–684. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60886-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, California: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Diclemente RJ, Coleen CP, Rose E, Sales J, Wingood GM, Crosby RA, Salazar LF. Psychosocial predictors of HIV-associated sexual behaviors and the efficacy of prevention interventions in adolescents at-risk for HIV Infection: What works and what doesn't work? Psychosomatic Medicine. 2008;70:598–605. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181775edb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis A, Cutura J, Dione N, Gillson I, Manuel C, Thongori J. Gender and Economic Growth in Kenya: Unleashing the power of women. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Chesney M, McKusick L, et al. Translating coping theory into an intervention. In: J E, editor. The Social Context of Coping. Plenum Press; New York, NY: 1991. pp. 239–260. [Google Scholar]

- Francis E. Migration and Changing Divisions of Labour: Gender relations and economic change in Koguta, western Kenya. Africa: Journal of the International African Institute. 1995;65(2):197–216. [Google Scholar]

- Gallant M, Maticka-Tyndale E. School-based HIV prevention programmes for African youth. Social Science & Medicine. 2004;58(7):1337–1351. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00331-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George LK, Ellison CG, Larson DB. Explaining the relationships between religious involvement and health. Psychological Inquiry. 2002;13(3):190–200. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie S, Greener R, Whiteside A, Whitworth J. Investigating the empirical evidence for understanding vulnerability and the associations between poverty, HIV infection and AIDS impact. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 7):S1–4. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000300530.67107.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst JH, Kay LS, Passin WF, Lyles CM, Crepaz N, Marin BV. A systematic review and meta-analysis of behavioral interventions to reduce HIV risk behaviors of Hispanics in the United States and Puerto Rico. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(1):25–47. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9151-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikamari L. Regional variation in initiation of childbearing in Kenya. African Population Studies. 2008;23(1):25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KS. Fear of Beggars: Stewardship and Poverty in Christian Ethics. Wm. B. Eerdman; Grand Rapids, Michigan: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan S. The Africanization of Missionary Christianity: History and Typology. Journal of Religion in Africa. 1986;16(3):166–186. [Google Scholar]

- Kiragu K, Zabin LS. The Correlates of Premarital Sexual Activity Among School-Age Adolescents in Kenya. International Family Planning Perspectives. 1993;19(3):92–109. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, Cohen HJ, Blazer DG, Pieper C, Meador KG, Shelp F, DiPasquale B. Religious coping and depression among elderly, hospitalized medically ill men. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1992;149(12):1693–1700. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.12.1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luginaah I, Elkins D, Maticka-Tyndale E, Landry T, Mathui M. Challenges of a pandemic: HIV/AIDS-related problems affecting Kenyan widows. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;60(6):1219–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maticka-Tyndale E, Gallant M, Brouillard-Coyle C, Holland D, Metcalfe K, Wildish J, Gichuru M. The sexual scripts of Kenyan young people and HIV prevention. finCulture Health & Sexuality. 2005;7(1):27–41. doi: 10.1080/13691050410001731080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Thoresen CE. Spirituality and health. In: Miller WR, editor. Integrating Spirituality into Treatment: Resources for Practitioners. American Psychological Association; Washington, D.C.: 1999. pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM. Behavioral interventions to reduce HIV-related sexual risk behavior: review and synthesis of meta-analytic evidence. AIDS and Behavior. 2008;12(3):335–353. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9313-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oluga M, Kiragu S, Mohamed MK, Walli S. “Deceptive” cultural practices that sabotage HIV/AIDS education in Tanzania and Kenya. Journal of Moral Education. 2010;39(3):365–380. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI. The psychology of religion and coping: Theory, research, and practice. Guilford Press; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Koenig HG, Perez LM. The many methods of religious coping: Development and initial validation of the RCOPE. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2000;56(4):519–543. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(200004)56:4<519::aid-jclp6>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Smith BW, Koenig HG, Perez L. Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1998;37(4):710–724. [Google Scholar]

- Parker RG, Easton D, Klein CH. Structural barriers and facilitators in HIV prevention: a review of international research. AIDS. 2000;14(Suppl 1):S22–32. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostosky SS, Wilcox BL, Wright MLC, Randall BA. The impact of religiosity on adolescent sexual behavior: A review of the evidence. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2004;19(6):677–697. [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS Report on the global HIV/AIDS epidemic. 2008.

- Watt MH, Maman S, Jacobson M, Laiser J, John M. Missed opportunities for religious organizations to support people living with HIV/AIDS: Findings from Tanzania. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(5):389–394. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]