Abstract

Background

Depression among women with sexual abuse histories is less treatment responsive than in general adult samples. One contributor to poorer treatment outcomes may be abused women’s difficulties in forming and maintaining secure relationships, as reflected in insecure attachment styles, which could also impede the development of a positive therapeutic alliance. The current study examines how attachment orientation (i.e., anxiety and avoidance) and development of the working alliance are associated with treatment outcomes among depressed women with histories of childhood sexual abuse.

Method

Seventy women seeking treatment in a community mental health center who had Major Depressive Disorder and a childhood sexual abuse history were randomized to Interpersonal Psychotherapy or treatment as usual.

Results

Greater attachment avoidance and weaker working alliance were each related to worse depression symptom outcomes; these effects were independent of the presence of comorbid Borderline Personality Disorder and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. The effect of avoidant attachment on outcomes was not mediated by the working alliance. Further, working alliance had a stronger effect on depression outcomes in the Interpersonal Psychotherapy group.

Conclusion

Understanding the influence of attachment style and the working alliance on treatment outcomes can inform efforts to improve treatments for depressed women with a history of childhood sexual abuse.

Keywords: Childhood Sexual Abuse, Attachment Orientation, Working Alliance, Depression Treatment, Interpersonal Psychotherapy

Women who experience childhood sexual abuse tend to report more insecure patterns of attachment [1] and more unstable, discordant relationships in adulthood [2–4]. Sexually abused women are also more likely to suffer from chronic, recurrent, and treatment-resistant depression than women without similar histories [5–7]. Interpersonal theories of depression integrate these findings by suggesting that depressed individuals have difficulties interacting with others and obtaining support, which can further exacerbate their depressive symptoms [8]. Thus, among depressed women with sexual abuse histories, insecure patterns of attachment may interfere with their ability to form a trusting alliance with their therapist and may contribute to the poorer treatment outcomes often seen among patients with insecure attachments [9; 10]. Identifying psychosocial contributors to poor outcomes in this particular population could help to guide efforts to strengthen treatments. To date no study has examined the association between adult attachment style, working alliance, and treatment response in depressed women with histories of childhood sexual abuse.

Attachment styles, or working models of the self and others, define interpersonal roles, inform beliefs about whether social support will be available from others, and direct ways of obtaining support [11]. These models are developed based on the responsiveness of caregivers during early childhood, but are continually shaped throughout life [12]. Though most accurately conceptualized dimensionally, adult attachment orientations can be broadly described as secure and insecure. Securely attached individuals expect that support is available when needed and are effectively able to request support. Insecurely attached individuals are described as expressing varying levels of attachment anxiety or avoidance. Anxiously attached persons value relationships, but engage in maladaptive behaviors due to intense fears of rejection. Individuals with avoidant attachment orientations engage in distancing behaviors to guard against discomfort experienced in interpersonal closeness. Greater attachment insecurity, and greater attachment avoidance in particular, has been shown to be associated with less benefit from depression treatment in populations without sexual abuse histories [13; 14].

The patient-therapist relationship, or working alliance, is among the relationships potentially impaired by an insecure attachment orientation [10; 15]. The working alliance has repeatedly been shown to be a critical determinant of therapeutic outcomes in other types of patient populations [16–18]. Cloitre has also demonstrated that the alliance is an important predictor of treatment outcome for women diagnosed with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder stemming from childhood abuse receiving Cognitive Behavior Therapy [19; 20]. Conceivably, a sexually abused patient’s attachment insecurities may interfere with the development of a strong working alliance in therapy, particularly an interpersonally oriented therapy [21]. The development of the working alliance requires that a patient develop a sense of trust and accept support from the therapist. A highly anxious or avoidant attachment orientation may inhibit development of the alliance and associated benefit in psychotherapy [10]. Although some have discussed the therapy relationship as an attachment relationship [22; 23], the question of whether anxious and avoidant attachment orientations affect the alliance for depressed women with a history of childhood sexual abuse is unexamined.

Although many studies have demonstrated that attachment insecurity is associated with the working alliance in clinical, non-abused samples [10; 15], few have examined the degree to which the working alliance functions as a mediator of the relationship between attachment orientation and treatment outcomes. Of these, some studies have shown that a more avoidant attachment orientation is mediated by the working alliance [24; 25], while others have failed to demonstrate a mediational relationship [26]. Sauer, Anderson, Gormley, Richmond, and Preacco [27] found that the working alliance was associated with greater reductions in symptoms during treatment and that attachment anxiety as measured by the Experiences in Close Relationships scale was associated with the working alliance and with symptom outcomes. However, they did not examine a mediational relationship.

In sum, research in general adult clinical samples indicates that client attachment orientation [14] and the quality of the working alliance influence treatment outcomes [16–18; 28]. However, findings on the effects of anxious and avoidant attachment dimensions on the working alliance have been mixed [15]. Despite the vulnerability of sexually abused women to relationship disturbances, it is not known how these relational factors may affect their treatment. Other research in depressed samples, including a study of sexually abused women [29], have identified psychiatric comorbidities that moderate depression treatment outcomes [7; 30]. In particular, Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) and Post-Traumatic Stress disorder (PTSD), both prevalent among sexually abused women, can complicate treatment [30–36]. Here, we investigate whether attachment style and the therapeutic alliance have prognostic value for depression treatment outcomes independent of BPD and PTSD.

The current study is a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial comparing Interpersonal-Psychotherapy (IPT) to treatment as usual (TAU) in a sample of depressed women with childhood sexual abuse histories [29]. Absent prior research on the relationship among attachment, working alliance, and depression outcomes in this population, and in light of the inconsistency of results regarding attachment styles and the alliance in general, we examined competing models: a mediation model wherein attachment affects outcome via the alliance, and an independent effects model wherein both attachment and alliance influence outcome independently. We also examined whether these relationships varied by treatment type. Hypotheses regarding treatment specificity of these relationships were considered exploratory as our small sample size prohibited a more complete examination. We expected that less avoidant women would experience greater benefit from IPT compared to highly avoidant women; in other words, IPT would capitalize on interpersonal strengths more than ameliorate deficits [37]. We also expected that the relationship between the working alliance and outcome would be more pronounced in IPT. Collaborative development of a specific interpersonal problem focus is a key component of IPT, which could enhance the alliance and thereby improve treatment outcomes [38]. Finally, we examined the relationships of session attendance to attachment anxiety and avoidance and the working alliance to determine whether attachment and alliance might influence treatment outcomes via session attendance.

Method

Participants

Participants were 70 women ages 19 to 57 years (M = 36.39, SD = 9.86) who met criteria for a current Major Depressive Episode (MDE), as identified by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Disorders (SCID)[39; 40], and reported a history of childhood sexual abuse in a structured trauma history interview [40]. Exclusion criteria were: active psychosis, a diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, mental retardation, or active substance abuse or dependence. Women were permitted to enter the study regardless of antidepressant prescription status. A total of 43 women reported having been prescribed antidepressant medications at the baseline assessment (23 of those in the IPT condition, 20 of those in the TAU condition). Demographic and diagnostic information is in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and Diagnostic Information

| Age | |

| Mean (SD) | 36.39 (9.87) |

| Racial Identity | |

| Caucasian; n (%) | 41 (58.6%) |

| African American; n (%) | 29 (41.4%) |

| Relationship Status | |

| Single, never married | 51 (72.9%) |

| Married or partnered | 19 (27.1%) |

| Source of Income | |

| Private | 29 (41.4%) |

| Public Assistance | 41 (58.6%) |

| Sessions Attended | |

| Mean (SD) | 9.81 (6.45) |

| Positive PTSD Diagnosis | 46 (65.7%) |

| Positive BPD Diagnosis | 26 (37.1%) |

Note: PTSD=Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, BPD=Borderline Personality Disorder. No significant differences between therapy groups were found on any demographic or diagnostic variable. Participants in the IPT group attended more treatment sessions than participants in TAU.

Materials

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory-2 (BDI) [41]. The BDI is a 21-item self-report measure of depressive symptoms over the previous two weeks, consistent with DSM-IV criteria. Scores on the BDI range from zero to 63. Scores of 0 to 13 indicate minimal symptoms of depression, 14 to 19 mild depression, 20 to 28 moderate depression, and 29 to 63 severe depression. The BDI has demonstrated good reliability and validity [41]. Internal consistencies of the BDI across all time points in the current sample were good (α = .88 - .95).

Working alliance was assessed using the Working Alliance Inventory (WAI)[42]. The WAI is a 12-item self-report measure of the therapeutic bond (e.g., “My therapist and I trust one another”) and the agreement between the therapist and client on the goals (e.g., “My therapist and I are working towards mutually agreed upon goals”), tasks, and procedures (e.g., “I believe the way we are working with my problem is correct”) of therapy [43]. Scores on the WAI Total Scale range from 12 to 84. Internal consistency of the WAI Total Scale was excellent (α = .94).

Attachment avoidance and anxiety were assessed using the Experiences in Close Relationships scale (ECR)[44]. The ECR is a 36-item self-report measure of how individuals respond in primary and romantic relationships. The ECR provides scales of attachment anxiety (e.g., “I worry a lot about my partner leaving me”) and avoidance (e.g., “I prefer not to be too close to romantic partners”). ECR scores range from one to seven with higher scores indicating greater attachment anxiety and avoidance. The two factor structure of the ECR has been replicated and the internal consistency and 6-week temporal stability of the ECR have been shown to be excellent [45]. Internal consistencies of the ECR scales in the current study were good (attachment anxiety α = .91; avoidance α = .94).

Procedures

Study procedures for this randomized controlled trial have been detailed elsewhere [29]. The institutional review board approved study procedures and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. In brief, all study participants received treatment in a community mental health center from staff clinicians. IPT and TAU clinicians had equivalent experience and degrees, predominantly master’s level. Manualized IPT [46] was conducted with the aim of 16 sessions within 36 weeks [47]. IPT therapists received weekly group supervision to address fidelity and videotaped sessions were reviewed and rated for adherence. TAU therapists had not received any training in IPT. Therapist effects were not controlled. TAU was individual psychotherapy, which TAU therapists described as supportive (53%), cognitive-behavioral or dialectical-behavioral (27%), integrated/eclectic (13%), and client-centered (7%). The assessment schedule was: SCID-I and the Borderline Personality Disorder module of the SCID-II [48] and ECR completed at baseline; WAI completed following the third therapy session; the BDI completed at baseline and 10, 24, and 36 weeks. Of those who began therapy, 66 completed the 10-week assessment and 53 completed the 24 and 36-week assessments.

Data Analysis

The current study compared competing models: 1) the mediation of the relationship between attachment and depression outcomes by working alliance and 2) the independent influence of attachment and working alliance on depression outcomes. To test the mediation model, we used the recommendations of Preacher and Hayes [49]. In order to test the independent effects model, Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) were used. The independent effects were adjusted for treatment condition, baseline depressive symptoms (BDI), Borderline Personality Disorder diagnosis, PTSD diagnosis, session attendance, racial identity (white or black), and relationship status (living with a spouse or partner versus not). These covariates were selected because they have established empirical or conceptual relationships to attachment, alliance, or depression treatment response [35; 36]. Diagnoses of Borderline Personality Disorder and PTSD were derived from SCID interviews; session attendance was the number of sessions attended within the 36 weeks of treatment. The outcome variable was BDI total score at 10, 24 and 36 weeks and modeled using the GEE approach, while the baseline BDI score was controlled. The independent variables were attachment anxiety, avoidance, and the WAI Total score. We present the results from the WAI Total only due to the high correlation among the WAI scales. All results were replicated using each of the subscales of the WAI.

Results

Demographic information and the prevalence of PTSD and BPD comorbidity are presented in Table 1. The current sample demonstrated significant PTSD and BPD comorbidity. Means and standard deviations of the BDI, the WAI, and the ECR scales can be found in Table 2. The sample was, on average, severely depressed at baseline. Although significant reductions in depression scores were obtained over time with more improvement in the IPT group [29], within-group treatment responses were highly variable.

Table 2.

Means and Standard Deviations of Depressive Symptoms, Attachment Style, and Working Alliance

| IPT M (SD) |

TAU M (SD) |

|

|---|---|---|

| BDI | ||

| Pre-treatment (n=70) | 34.41 (10.36) | 34.82 (10.28) |

| 10-weeks (n=66) | 23.91 (14.35) | 29.84 (13.68) |

| 24-weeks (n=53) | 23.90 (14.74) | 29.84 (13.68) |

| 36-weeks (n=53) | 22.87 (15.54) | 27.14 (13.64) |

| ECR (assessed at baseline) | ||

| Attachment Anxiety | 4.80 (1.02) | 4.20 (1.18) |

| Attachment Avoidance | 4.24 (1.22) | 3.96 (1.41) |

| WAI (assessed following session 3) | ||

| Overall Alliance | 64.03 (11.47) | 58.70 (11.60) |

| Therapeutic Bond | 21.32 (3.72) | 19.52 (3.89) |

| Agreement on Tasks of Therapy | 21.56 (4.47) | 19.70 (4.93) |

| Agreement on Goals of Therapy | 21.15 (4.38) | 19.46 (4.17) |

Note: BDI=Beck Depression Inventory, HRSD=Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, ECR=Experiences in Close Relationships Scale, WAI=Working Alliance Inventory, IPT=Interpersonal Psychotherapy, TAU=Treatment as usual.

Test of Mediation

Consistent with advances in mediational analyses in clinical psychological research, we used the recommendations of Preacher and Hayes [49]. Although this approach does not employ a sequence of regression analyses [50], it requires the predictor variable to be associated with the proposed mediator. The relationships between attachment anxiety and avoidance with the working alliance scales were non-significant (ranging from r = −.01 to r = .16, all p-values > .05). Therefore, no further mediation testing was done.

Test of Independent Contributions

Lower attachment avoidance at baseline was associated with greater reductions in depressive symptoms (standardized coefficient=3.58, χ2(1) = 7.70, p=.0010). This standardized coefficient was obtained by standardizing the predictor(s) and the continuous covariates in each of GEE models. This coefficient indicates that each 1.31 point (one standard deviation) increase in the rating of attachment avoidance will correspond to an average 3.58-point increase in BDI scores over time. Attachment anxiety was not associated with changes in depressive symptom severity over time (χ2(1)=1.05, p=.3051). A stronger working alliance was associated with greater benefit from treatment (WAI: standardized coefficient=-4.32, χ2(1)=10.83, p=.0010). This coefficient indicates that each 11.74 point (one standard deviation) increase in the rating of the working alliance will correspond to an average 4.32-point decrease in BDI scores over time.

Treatment Specificity

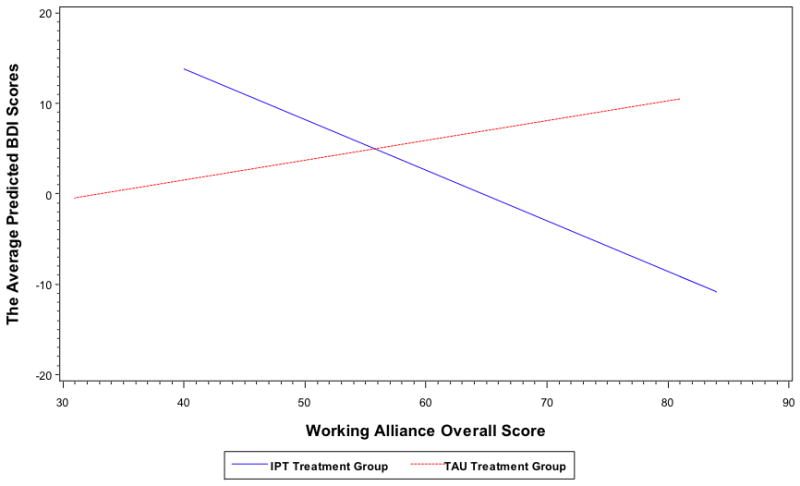

Due to our limited sample size and concerns about power, we removed all covariates except baseline depression severity in analyses examining the interaction between treatment type and the attachment and alliance scales. A significant interaction was found between treatment type and WAI total scores (χ2(1)=6.94, p=.0084). Higher working alliance scores were associated with greater improvements in depressive symptoms for the IPT group (χ2(1)=6.36, p=.0116), but not for TAU (χ2(1)=1.81, p=.1783)(see Figure 1). Although ratings of alliance were higher in the IPT condition (M = 64.03, SD = 11.47; TAU M = 58.70, SD = 11.60), this difference was just outside the threshold for statistical significance (t(59)=1.79, p=.079). Attachment orientation did not interact with treatment type to predict depression symptoms.

Figure 1. The Moderation of the Relationship between Working Alliance Overall Score and BDI Scores by Treatment Type.

Note: Only the interaction between the overall WAI score and treatment condition is shown. The interactions between each of the WAI scales (Therapeutic Bond, Agreement on the Tasks, and Goals of Therapy) and treatment condition as it relates to changes in BDI scores over time were similar to that depicted here. Tests of the simple slopes indicated that that there was a significant downward slope for the IPT condition (χ2(1)=6.94, p<.01). The simple slope of TAU was not significant (χ2(1)=1.81, p>.05).

Attachment, Alliance, and Session Attendance

All correlations between attachment styles and working alliance domains with overall number of sessions attended were non-significant (r = .07 to r = .21, all p-values > .05). Clients attended a greater number of sessions in the IPT group (MIPT=12.97, SD=1.07 v. MTAU=6.27, SD=.73; t(68)=5.052, p=.000). However, treatment outcome was not significantly correlated with the number of sessions attended (r = −.197).

Discussion

The current study examined the effects of attachment orientation and the working alliance on treatment outcomes among depressed women with childhood sexual abuse histories. Patients with less attachment avoidance reported greater improvements in their depressive symptoms at the end of treatment. Although less avoidant women appeared to benefit more from treatment than highly avoidant women, this difference was not more pronounced in the IPT treatment group. Findings also showed that patients with more positive working alliances with their therapists reported fewer depressive symptoms at treatment conclusion, after accounting for baseline depressive symptoms. Consistent with our exploratory hypotheses, the working alliance was more strongly associated with treatment outcome in IPT than TAU. Session attendance was not associated with attachment or the working alliance. Importantly, these relationships were independent of the influence of PTSD and BPD diagnoses, both of which are highly prevalent in depressed women with childhood sexual abuse histories and can disrupt treatment progress [7; 30; 36].

These findings extend previous research by showing that the relationship between the working alliance and treatment outcome is important among depressed women with sexual abuse histories – a previously unexamined population shown to experience severe interpersonal and attachment difficulties [16–18]. Findings further suggest that the effect of the alliance was particularly important for women who received IPT, an interpersonally focused manualized intervention for depression. This finding must be interpreted with caution due to the small sample size, the removal of covariates from this analysis, and the variability in the treatments in the TAU condition. We speculate that the shared treatment formulation and collaborative identification of an interpersonally specific problem area (i.e., interpersonal conflicts, role transitions, grief and loss, and maladaptive interpersonal patterns) within IPT may have fostered better treatment outcomes through development of the working alliance [29; 38; 47].

The finding that women in the IPT condition reported a marginally stronger working alliance compared to those in the TAU condition also supports this interpretation. These results are consistent with data suggesting that patients report a stronger early working alliance in manualized versus non-manualized treatment [51]. Establishing a collaborative relationship with a specific interpersonal problem focus in treatment may influence a number of important factors, such as motivation for change, expectation for success, and willingness to practice new skills. Alternatively, although all therapists received equivalent levels of clinical supervision, IPT therapists may have experienced greater confidence in the therapy they delivered as a result of having received structured training on a specific type of psychotherapy. Such confidence may have better engaged clients and thereby influenced the alliance.

Results are also consistent with studies demonstrating that greater attachment avoidance is associated with less benefit from therapy [14]. We speculate that avoidant women may have had less opportunity and motivation to practice the interpersonal skills that were addressed in therapy. Such reduced opportunities may derive from more avoidant women having fewer relationships or, as the core of avoidant attachment might suggest, motivation to engage with others. Women exhibiting more anxious attachment, which was unrelated to treatment outcome, may have been more effective (at moderate levels of attachment anxiety) and motivated (at high levels) to engage with others and practice interpersonal skills outside of treatment. An alternative explanation is that the available treatments were not a good content match to more avoidant women, who might prefer a less interpersonally focused treatment, such as behavioral activation treatment. The latter explanation seems to us less likely, however, given that more avoidant women gave equivalent ratings for the working alliance, suggesting an endorsement of the treatment approach.

The lack of a relationship between attachment style and the working alliance seems at first counterintuitive. However, Smith and colleagues’ [15] review of the literature indicates that specific attachment styles are inconsistently associated with working alliance. One possible explanation for the independence of attachment orientation and working alliance is that the complex, nuanced drives of intimate attachment may be different from the interpersonal dynamics of the working alliance [22; 52]. An alternative explanation is that patients’ attachment needs vis-à-vis their therapists may not be ignited in the early-stage of treatment when working alliance is assessed.

Clinical Implications

The current findings suggest that therapy with depressed women with childhood sexual abuse histories must address both attachment avoidance and the alliance, perhaps with different approaches. Conceivably, attachment orientation could be conceptualized as an interpersonal problem area within IPT [53]. The addition of a problem area that explicitly addresses the client’s attachment style is fully consistent with IPT’s foundation in attachment theory [46]. Focal targeting of attachment style could not only facilitate acute symptom alleviation, but could also reduce clients’ vulnerability to distress by altering the working models that serve to place individuals at risk for relapse [54]. This may be especially important in populations like depressed, sexually abused women who experience significant risk of symptom relapse and severe attachment disturbance [2; 6].

Our speculation that avoidant women may have fewer opportunities and motivation to practice the interpersonal skills learned in therapy is supported by data demonstrating that insecurely attached individuals have fewer healthy relationships [3; 55]. Clients may experience difficulties when they attempt to obtain their interpersonal needs through effective communication in predominantly unhealthy relationships. Therapists might begin treatment with an extensive evaluation of the client’s social support system to determine whether an expansion of this system is required. Additionally, therapists of patients with high attachment avoidance may find it helpful to explore patients’ motivations for increased social connections.

Our finding that attachment orientation and working alliance are unrelated indicates that strong alliances can be effectively developed with patients who have insecure attachment styles. Previous research has demonstrated that a positive working alliance can be supported by balance and flexibility in the structuring of the treatment, being responsive to the needs of clients, attention and awareness of cultural factors influencing treatment, genuineness, and the facilitation of affective expression [56–58]. The apparent greater association of the working alliance with outcomes in the IPT condition suggests that a more structured, collaborative, and interpersonally-focused approach may be beneficial [38] for depressed women with childhood sexual abuse histories.

Limitations

The current study assessed working alliance following the third treatment session. As such, our results speak only to the therapeutic relationship during the early phase of treatment and do not examine the evolution of the patient-therapist relationship over the course of therapy [59]. Future research should examine longitudinally whether changes in attachment and working alliance affect treatment outcome. The assessments of depression, the working alliance, and attachment orientation were all self-report. Future studies should employ multiple methods (e.g., interviews) to determine the extent to which the self-report method may have influenced results. This may be particularly important for the measure of attachment, given concerns about the correspondence between self-report and interview based measures of attachment orientation [60]. Furthermore, the ECR is a measure of adult attachment in romantic relationships, which may differ in important ways from the therapeutic relationship [22]. More research is needed to understand how attachment styles in general and in specific relationships relate to each other and to treatment process variables [12]. Although TAU therapists provided post-treatment descriptions of their therapy model, it cannot be certain what treatment methods were used in TAU, suggesting caution in considering how the alliance influences treatment outcomes across different treatment types.

Conclusion

The current study is the first to examine how attachment orientation and the development of the working alliance influence treatment outcomes for depressed women with childhood sexual abuse histories. Less attachment avoidance and a stronger working alliance were independently associated with greater benefit from treatment. Clinicians can be encouraged that, despite the social impairments experienced by depressed women with childhood sexual abuse histories [2; 4; 55], a positive working alliance can be achieved and related benefits obtained, even considering BPD and PTSD comorbidity. Although both groups experienced reduced depressive symptoms, the majority of clients remained symptomatic at the end of treatment [29]. This is consistent with data demonstrating that the depression in this population can be highly resistant to treatment [6; 7]. Additional research is needed to understand more fully the factors that influence treatment outcomes for depressed women with a history of childhood sexual abuse.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by National Institute of Mental Health grants K23MH64528 and T32MH020061.

References

- 1.Rumstein-McKean O, Hunsley J. Interpersonal and family functioning of female survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Clinical Psychology Review. 2001;21(3):471–490. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexander PC. Childhood trauma, attachment, and abuse by multiple partners. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2009;1(1):78–88. [Google Scholar]

- 3.DiLillo D. Interpersonal functioning among women reporting a history of childhood sexual abuse: empirical findings and methodological issues. Clinical Psychology Review. 2001;21(4):553–76. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mickelson KD, Kessler RC, Shaver PR. Adult attachment in a nationally representative sample. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73(5):1092–1106. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.5.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zlotnick C, Mattia J, Zimmerman M. Clinical features of survivors of sexual abuse with major depression. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2001;25(3):357–367. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00251-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zlotnick C, Ryan CE, Miller IW, Keitner GI. Childhood Abuse and Recovery from Major Depression. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1995;19(12):1513–1516. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(95)00098-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zlotnick C, Warshaw M, Shea MT, Keller MB. Trauma and chronic depression among patients with anxiety disorders. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1997;65(2):333–336. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.2.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coyne JC. Toward an Interactional Description of Depression. Psychiatry-Interpersonal and Biological Processes. 1976;39(1):28–40. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1976.11023874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cyranowski JM, Bookwala J, Feske U, et al. Adult attachment profiles, interpersonal difficulties, and response to interpersonal psychotherapy in women with recurrent major depression. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2002;21(2):191–217. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diener MJ, Monroe JM. The Relationship Between Adult Attachment Style and Therapeutic Alliance in Individual Psychotherapy: A Meta-Analytic Review. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 2011;48:237–248. doi: 10.1037/a0022425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bowlby J. A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fraley R. A connectionist approach to the organization and continuity of working models of attachment. Journal of Personality. 2007;75(6):1157–1180. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyer B, Pilkonis PA, Proietti JM, et al. Attachment styles and personality disorders as predictors of symptom course. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2001;15(5):371–389. doi: 10.1521/pedi.15.5.371.19200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McBride C, Atkinson L, Quilty LC, Bagby R. Attachment as moderator of treatment outcome in major depression: A randomized control trial of interpersonal psychotherapy versus cognitive behavior therapy. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2006;74(6):1041–1054. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.6.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith AE, Msetfi RM, Golding L. Client self rated adult attachment patterns and the therapeutic alliance: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.12.007. No Pagination Specified. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horvath AO, Del Re AC, Fluckiger C, Symonds D. Alliance in individual psychotherapy. Psychotherapy. 2011;48(1):9–16. doi: 10.1037/a0022186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin DJ, Garske JP, Davis MK. Relation of the therapeutic alliance with outcome and other variables: A meta-analytic review. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2000;68(3):438–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krupnick JL, Sotsky SM, Simmens S, et al. The role of the therapeutic alliance in psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy outcome: findings in the National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1996;64(3):532–9. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.3.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cloitre M, Koenen KC, Cohen LR, Han H. Skills training in affective and interpersonal regulation followed by exposure: A phase-based treatment for PTSD related to childhood abuse. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2002;70(5):1067–1074. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.5.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cloitre M, Stovall-McClough KC, Miranda R, Chemtob CM. Therapeutic alliance, negative mood regulation, and treatment outcome in child abuse-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(3):411–416. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krupnick JL, Sotsky SM, Simmens S, et al. The role of the therapeutic alliance in psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy outcome: Findings in the National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1996;64(3):532–539. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.3.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mallinckrodt B, Gantt DL, Coble HM. Attachment patterns in the psychotherapy relationship: Development of the Client Attachment to Therapist Scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1995;42(3):307–317. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meyer B, Pilkonis PA. Attachment style. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 2001;38(4):466–472. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hardy GE, Cahill J, Shapiro DA, et al. Client interpersonal and cognitive styles as predictors of response to time-limited cognitive therapy for depression. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2001;69(5):841–5. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.5.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Byrd KR, Patterson CL, Turchik JA. Working alliance as a mediator of client attachment dimensions and psychotherapy outcome. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 2010;47(4):631–636. doi: 10.1037/a0022080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reis S, Grenyer BFS. Fearful attachment, working alliance and treatment response for individuals with major depression. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2004;11(6):414–424. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sauer EM, Anderson MZ, Gormley B, et al. Client attachment orientations, working alliances, and responses to therapy: a psychology training clinic study. Psychotherapy research: journal of the Society for Psychotherapy Research. 2010;20(6):702–11. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2010.518635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horvath AO, Symonds BD. Relation between Working Alliance and Outcome in Psychotherapy - a Metaanalysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1991;38(2):139–149. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Talbot NL, Chaudron LH, Ward EA, et al. A Randomized Effectiveness Trial of Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Depressed Women with Sexual Trauma Histories in Community Mental Health Care. Psychiatric Services. 2011 doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.62.4.374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newton-Howes G, Tyrer P, Johnson T. Personality disorder and the outcome of depression: meta-analysis of published studies. The British journal of psychiatry: the journal of mental science. 2006;188:13–20. doi: 10.1192/bjp.188.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walker EA, Katon WJ, Russo J, et al. Predictors of outcome in a primary care depression trial. Journal of general internal medicine. 2000;15(12):859–67. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.91142.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frank E, Shear MK, Rucci P, et al. Influence of panic-agoraphobic spectrum symptoms on treatment response in patients with recurrent major depression. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157(7):1101–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.7.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zlotnick C, Bruce SE, Weisberg RB, et al. Social and health functioning in female primary care patients with post-traumatic stress disorder with and without comorbid substance abuse. Comprehensive psychiatry. 2003;44(3):177–83. doi: 10.1016/S0010-440X(03)00005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oquendo MA, Friend JM, Halberstam B, et al. Association of comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and major depression with greater risk for suicidal behavior. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160(3):580–2. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.3.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Green BL, Krupnick JL, Chung J, et al. Impact of PTSD Comorbidity on One-Year Outcomes in a Depression Trial. Journal of clinical psychology. 2006;62(7):815–835. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cyranowski J, Frank E, Winter E, et al. Personality pathology and outcome in recurrently depressed women over 2 years of maintenance interpersonal psychotherapy. Psychological Medicine: A Journal of Research in Psychiatry and the Allied Sciences. 2004;34(4):659–669. doi: 10.1017/S0033291703001661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barber JP, Muenz LR. The role of avoidance and obsessiveness in matching patients to cognitive and interpersonal psychotherapy: Empirical findings from the Treatment for Depression Collaborative Research Program. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1996;64(5):951–958. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.5.951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tryon GS, Winograd G. Goal consensus and collaboration. Psychotherapy. 2011;48(1):50–7. doi: 10.1037/a0022061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders. New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Talbot NL, Houghtalen RP, Duberstein PR, et al. Effects of group treatment for women with a history of childhood sexual abuse. Psychiatric Services. 1999;50:686–692. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.5.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Horvath AO, Greenberg LS. Development and validation of the Working Alliance Inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1989;36(2):223–233. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bordin ES. The generalizability of the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 1979;16(3):252–260. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brennan KA, Clark CL, Shaver PR. Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sibley C, Liu J. Short-term temporal stability and factor structure of the revised experiences in close relationships (ECR-R) measure of adult attachment. Personality and Individual Differences. 2004;36(4):969–975. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stuart S, Robertson M. Interpersonal Psychotherapy: A Clinician’s Guide. Hodder Arnold; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Talbot NL, Conwell Y, O’Hara MW, et al. Interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed women with sexual abuse histories: a pilot study in a community mental health center. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2005;193(12):847–50. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000188987.07734.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders, (SCID-II) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 2004;36:717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The Moderator Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological-Research - Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Langer DA, McLeod BD, Weisz JR. Do treatment manuals undermine youth-therapist alliance in community clinical practice? Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2011 doi: 10.1037/a0023821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mallinckrodt B, Coble HM, Gantt DL. Toward differentiating client attachment from working alliance and transference: Reply to Robbins (1995) Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1995;42(3):320–322. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stuart S. What is IPT? the basic principles and the inevitability of change. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy. 2008;38(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ravitz P, Maunder R, McBride C. Attachment, contemporary interpersonal theory and IPT: An integration of theoretical, clinical, and empirical perspectives. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy. 2008;38(1):11–21. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nelson EC, Heath AC, Madden PA, et al. Association between self-reported childhood sexual abuse and adverse psychosocial outcomes: results from a twin study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(2):139–45. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ackerman SJ, Hilsenroth MJ. A review of therapist characteristics and techniques negatively impacting the therapeutic alliance. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 2001;38(2):171–185. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ackerman SJ, Hilsenroth MJ. A review of therapist characteristics and techniques positively impacting the therapeutic alliance. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003;23(1):1–33. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(02)00146-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Norcross JC, Wampold BE. Evidence-based therapy relationships: research conclusions and clinical practices. Psychotherapy. 2011;48(1):98–102. doi: 10.1037/a0022161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Safran JD, Muran JC, Eubanks-Carter C. Repairing alliance ruptures. Psychotherapy. 2011;48(1):80–7. doi: 10.1037/a0022140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bartholomew K, Shaver PR. In: Methods of assessing adult attachment: Do they converge? Simpson Jeffry A., editor. 1998. pp. 25–45. [Google Scholar]