Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To investigate the association between overactive bladder (OAB) and C-reactive protein (CRP) in a population-based sample of men and women.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Epidemiological survey of urological symptoms among men and women aged 30–79 years. A multi-stage stratified cluster design was used to randomly sample 5503 adults from the city of Boston. Analyses were conducted on 1898 men and 1854 women with available CRP levels.

The International Continence Society defines OAB as ‘Urgency with or without urge incontinence, usually with frequency and nocturia.’ OAB was defined as: (1) urgency, (2) urgency with frequency, and (3) urgency with frequency and nocturia.

Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) of the CRP and OAB association were estimated using logistic regression.

RESULTS

Prevalence of OAB increased with CRP levels in both men and women.

In men, adjusted ORs (95% CI) per log10(CRP) levels were 1.90 (1.26–2.86) with OAB defined as urgency, 1.65 (1.06–2.58) with OAB defined as urgency and frequency, and 1.92 (1.13–3.28) with OAB defined as urgency, frequency and nocturia.

The association was more modest in women with ORs (95% CI) of 1.53 (1.07–2.18) for OAB as defined urgency, 1.51 (1.02–2.23) for OAB defined as urgency and frequency, and 1.34 (0.85–2.12) for OAB defined as urgency, frequency and nocturia.

CONCLUSIONS

Results show a consistent association of increasing CRP levels and OAB among both men and women.

These results support our hypothesis for the role of inflammation in the development of OAB and a possible role for anti-inflammatory agents in its treatment.

Keywords: C-reactive protein, epidemiology, inflammation, overactive bladder

INTRODUCTION

Overactive bladder (OAB) is a common condition in aging men and women with significant impact on quality of life and economic burden [1–6]. Population-based epidemiological studies suggest a role for inflammation in the development and progression of LUTS: data on men ≥ 60 years from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey show that men with detectable C-reactive protein (CRP) levels were more likely to report LUTS than men with undetectable CRP levels [7]; longitudinal data from the Olmsted County Study show an association of elevated baseline CRP levels with increased storage LUTS symptoms in men aged ≥ 40 years [8]; and previous analyses of the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey showed a significant cross-sectional association of CRP levels and LUTS in both men and women [9]. Although detrusor overactivity is often considered the primary cause of OAB, the pathophysiology of OAB and the potential role of inflammatory processes in the development of OAB is not well understood. Although evidence of chronic inflammation in BPH is well documented [10–12], few studies have addressed the role of inflammation in OAB in women.

Previous analyses of the BACH Survey have shown a significant cross-sectional association of CRP levels and overall LUTS, as assessed by the American Urological Association Symptom Index (AUA-SI), in both men and women [9]. The objectives of the present analysis were (1) to investigate the association between CRP levels and OAB as defined by the ICS, and (2) to assess the association of CRP with components of OAB (urgency, frequency, nocturia) and their overlap.

METHODS

The BACH survey is a population-based epidemiological survey of urological symptoms and risk factors in a randomly selected sample (2301 men and 3202 women). Detailed methods have been described elsewhere [13]. A multi-stage stratified design was used to recruit approximately equal numbers of subjects according to age, gender and race/ethnicity (black, Hispanic and white) from April 2002 to June 2005. Interviews were completed with 63.3% of eligible subjects. All protocols and informed consent procedures were approved by the New England Research Institutes’ Institutional Review Board.

Data were obtained during a 2-h in-person interview, conducted by a trained (bilingual) phlebotomist/interviewer, in the subject’s home. Following written informed consent, a venous blood sample (20 mL) was obtained and height, weight and hip and waist circumference were measured along with self-reported information on medical and reproductive history, major comorbidities, lifestyle and psychosocial factors, and symptoms of urogynaecological conditions. Medication use in the past month was collected using a combination of drug inventory and self-report with a prompt by indication.

The ICS defines OAB as ‘Urgency with or without urge incontinence, usually with frequency and nocturia’ [14]. The definitions of urgency frequency, and nocturia used in this analysis are presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Definition of urgency, frequency and nocturia in the Boston Area Community Health study

| Symptom | Questions | Symptom present if response was: |

|---|---|---|

| Urgency | (1) During the last month, how often have you had difficulty postponing urination? | fairly often, usually, or almost always |

| (2) During the last month, how often have you had a strong urge or pressure to urinate immediately with no, or little warning? | fairly often, usually, or almost always | |

| (3) In the last 7 days, how many times did you feel a strong urge or pressure that signalled the need to urinate immediately? | four times or more | |

| Frequency | (1) During the last month, how often have you had to urinate again less than two hours after you finished urination? | fairly often, usually, or almost always |

| (2) During the last month, how often have you had frequent urination during the day? | fairly often, usually, or almost always | |

| (3) In the last 7 days, on average, how many times have you had to go to the bathroom to empty your bladder during the day? | eight times or more | |

| Nocturia | (1) During the last month, how often have you had to get up to urinate more than once during the night? | fairly often, usually, or almost always |

| (2) In the last 7 days, on average, how many times have you had to go to the bathroom to empty your bladder during the night after falling asleep? | two times or more |

Based on the ICS definition, we used three definitions of OAB: (1) urgency with or without frequency and/or nocturia; (2) urgency with frequency, with or without nocturia; and (3) urgency with frequency and nocturia

The concentration of CRP was determined using an immunoturbidimetric assay on the Hitachi 917 analyser (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA), using reagents and calibrators from DiaSorin (Stillwater, MN, USA). In this assay, an antigen–antibody reaction occurs between CRP in the sample and an anti-CRP antibody that has been sensitized to latex particles, and agglutination occurs. This antigen–antibody complex causes an increase in light scattering, which is detected spectrophotometrically, with the magnitude of the change being proportional to the concentration of CRP in the sample. Assays were performed at the Children’s Hospital Medical Center Research Laboratories, Boston, MA, USA, with a reported sensitivity of 0.03 mg/L. The coefficients of variation at concentrations of 0.91, 3.07 and 13.38 mg/L are 2.81, 1.61 and 1.1%, respectively.

Covariates included

self-reported race/ethnicity (black, Hispanic, white), body mass index categorized as < 25.0, 25.0–29.9 and ≥ 30.0 kg/m2, physical activity assessed using the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly and categorized as low (< 100), medium (100–250) and high (> 250) [15], alcohol consumption as alcoholic drinks consumed per day (0, < 1, 1–2.9, ≥ 3), smoking as never, former and current. The socioeconomic status index was calculated using a combination of education and household income [16]. Socioeconomic status was categorized as low (lower 25% of the distribution of the socioeconomic status index), middle (middle 50%) and high (upper 25%). Comorbid conditions included were heart disease, diabetes and hypertension. Comorbidities were defined as a yes response to ‘Have you ever been told by a healthcare provider that you have or had…?’ Heart disease was defined by self-report of myocardial infarction, angina, congestive heart failure, coronary artery bypass, or angioplasty stent. Presence of depressive symptoms was assessed using the abbreviated Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression scale [17]. Participants reporting five or more depressive symptoms (out of eight) were considered to have clinically significant depression. Medication use included in the analysis included use of diuretics, antidepressants, prescription medications for LUTS and use of anti-inflammatory and other medications that could affect CRP levels (both prescription and over-the-counter). A detailed list of medications included in each category was published previously [9].

Analyses were conducted separately for men and women. Blood samples were obtained from 1899 (82.5%) men and 1858 (58.0%) women. CRP levels were obtained for 1898 men and 1854 women. A log10 trasnformation was used to approximate normal distribution of continuous CRP levels. The CRP levels were also categorized as < 1 mg/L, 1–3 mg/L, > 3 mg/L [18]. Confounder adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% CI were estimated using multivariate logistic regression to assess the association of CRP levels and OAB. Age and race/ethnicity were always included in multivariate models as design variables. Additional covariates were included in models if they were significant (P < 0.05) or if they changed the OR for the CRP and OAB association by > 10%.

The proportion of participants with missing data was 0.13% (n = 7) for urgency, 0.15% (n = 8 for frequency), 0.13% (n = 7) for nocturia, 0.9% (n = 33) for comorbid conditions and depressive symptoms, 1.0% (n = 37) for lifestyle variables (physical activity, alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking) and 4.7% (n = 178) for the socioeconomic status index. Overall, 6.7% participants had missing data on at least one of these variables. A multiple imputation technique was used to obtain plausible values for missing data [19]. To be representative of the city of Boston, observations were weighted as inversely proportional to their probability of selection [20]. Weights were post-stratified to the Boston population according to the 2000 census. Analyses were conducted in version 9.1 of SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and version 9.0.1 of SUDAAN (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA).

RESULTS

The characteristics of the analysis sample are presented in Table 2. Prevalence of OAB by gender, age and CRP levels is presented in Fig. 1. An increase in prevalence of OAB with age is observed among both men and women with prevalence increasing after age 50 years with over 15% of men and over 20% of women reporting OAB symptoms (Fig. 1). Prevalence of OAB also increased with higher CRP levels. Among men, OAB symptoms increased with CRP levels > 3 mg/L. Among women, prevalence of OAB symptoms increased with CRP levels > 1 mg/L. There was substantial overlap of urgency, frequency and nocturia (Fig. 2). Urgency alone was observed in < 3% of men and women and most participants with urgency also reported both frequency and nocturia.

TABLE 2.

Descriptive characteristics of analysis sample

| Men N = 1898 |

Women N = 1854 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 30–39 | 512 (37.2) | 444 (33.6) |

| 40–49 | 553 (25.8) | 484 (24.4) | |

| 50–59 | 436 (17.8) | 474 (18.3) | |

| 60–79 | 397 (19.2) | 453 (23.7) | |

| Race | White | 710 (37.4*) | 703 (37.9*) |

| Black | 537 (28.3*) | 582 (31.4*) | |

| Hispanic | 651 (34.3*) | 569 (30.7*) | |

| Socioeconomic status | Low | 784 (23.9) | 837 (29.2) |

| Middle | 787 (48.9) | 751 (46.3) | |

| High | 327 (27.2) | 266 (24.6) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | < 25.0 | 495 (26.8) | 452 (34.3) |

| 25.0–29.9 | 740 (39.5) | 538 (26.7) | |

| ≥30.0 | 664 (33.7) | 864 (39.0) | |

| Physical activity (PASE) | Low < 100) | 534 (25.5) | 646 (25,4) |

| Moderate (200–250) | 899 (48.2) | 920 (53.6) | |

| High(> 250) | 465 (26.3) | 287 (21.0) | |

| Smoking | Never | 815 (45.6) | 1702 (50.2) |

| Former | 541 (28.9) | 776 (27.2) | |

| Current | 542 (25.6) | 721 (22.6) | |

| Alcohol consumption (drinks per day) | None | 636 (26.2) | 915 (41.3) |

| < 1/day | 694 (40.2) | 716 (42.7) | |

| 1–2.9/day | 362 (24.4) | 179 (13.2) | |

| ≥3/day | 206 (9.2) | 44 (2.8) | |

| Heart disease | 182 (9.6) | 188 (8.6) | |

| Diabetes | 232 (9.6) | 262 (9.6) | |

| Hypertension | 587 (26.4) | 641 (28.1) | |

| Depression | 317 (14.0) | 486 (20.7) | |

| Medication use | Anti-inflammatory | 884 (52.6) | 1117 (61.8) |

| LUTS medications | 113 (4.4) | 82 (3.8) | |

| Diuretics | 188 (7.3) | 319 (14.0) | |

| Antidepressants | 199 (12.6) | 319 (17.2) | |

| C-reactive protein (CRP; mg/L) | Mean (SE) | 2.67 (0.27) | 3.50 (0.22) |

| Median | 1.08 | 1.49 | |

| 25th, 75th percentiles | 0.47, 2.51 | 0.60, 3.85 | |

| CRP | < 1 mg/L | 843 (47.3) | 558 (37.3) |

| 1–3 mg/L | 655 (32.9) | 580 (32.0) | |

| > 3 mg/L | 580 (19.8) | 716 (30.7) | |

| Log[CRP(mg/L)] | Mean (SE) | 0.11 (0.05) | 0.45 (0.05) |

| Median | 0.08 | 0.40 | |

| 25th, 75th percentiles | −0.76, 0.92 | −0.51, 1.35 |

All values are n (weighted %) except where marked by an asterisk, indicating unweighted %.

FIG. 1.

Prevalence of overactive bladder by gender, age and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels.

FIG. 2.

Area-proportional Venn diagrams showing the overlap between urgency, frequency and nocturia in men and women. Numbers displayed are the proportions among participants reporting at least one of the three symptoms. Among both men and women, urgency is usually accompanied by frequency and/or nocturia with < 3% reporting urgency alone.

Results of multivariate analyses of the association of CRP levels and OAB symptoms are presented in Table 3. Among men, log10(CRP) levels used as a continuous variable was associated with all three definitions of OAB (any report of urgency, urgency with frequency, or urgency with both frequency and nocturia). The observed ORs were similar for OAB defined as urgency (OR = 1.90) and for urgency with frequency and nocturia (OR = 1.92), whereas the OR for OAB defined as urgency with frequency was slightly smaller (OR = 1.65). With CRP levels grouped into three categories, men with elevated CRP levels (> 3 mg/L) had a twofold increase in odds of OAB defined as any report of urgency (OR = 2.05, 95% CI 1.24–3.40) compared with men with CRP levels < 1 mg/L. This association was attenuated when the OAB definition was restricted to urgency with frequency (OR = 1.59) or urgency with both frequency and nocturia (OR = 1.67).

TABLE 3.

Association of C-reactive protein (CRP) levels and overactive bladder (OAB) by gender

| CRP | Urgency | Urgency with Frequency | Urgency with Frequency and Nocturia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men* | Log10(CRP) | 1.90 (1.26, 2.86) | 1.65 (1.06, 2.58) | 1.92 (1.13, 3.28) |

| < 1 mg/L | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| 1–3 mg/L | 1.17 (0.68, 2.00) | 1.13 (0.62, 2.06) | 1.18 (0.58, 2.41) | |

| > 3 mg/L | 2.05 (1.24, 3.40) | 1.59 (0.93, 2.73) | 1.67 (0.90, 3.11) | |

| P-trend‡ | 0.007 | 0.108 | 0.112 | |

| Women† | Log10(CRP) | 1.53 (1.07, 2.18) | 1.51 (1.02, 2.23) | 1.34 (0.85, 2.12) |

| < 1 mg/L | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| 1–3 mg/L | 2.16 (1.24, 3.76) | 2.06 (1.13, 3.76) | 1.89 (0.93, 3.84) | |

| > 3 mg/L | 1.59 (0.95, 2.67) | 1.69 (0.95, 2.99) | 1.48 (0.74, 2.95) | |

| P-trend‡ | 0.115 | 0.101 | 0.361 |

OAB defined as: (1) any report of urgency, (2) urgency with frequency, (3) urgency with frequency and nocturia. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

ORs for men adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), diabetes, depressive symptoms.

ORs for women adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, BMI, heart disease, depressive symptoms, and lower urinary tract symptom medications use

P value for trend test across the three categories of CRP.

Among women, a significant association between continuous log10(CRP) levels and OAB was observed with OAB defined as any report of urgency (OR = 1.53) or urgency with frequency (OR = 1.51). The OR for OAB defined as urgency with both frequency and nocturia was attenuated (OR = 1.34) and not significant. Using CRP levels catergorized in three groups, increased odds of OAB were observed among women with moderately elevated CRP levels (1–3 mg/L) compared with women with low CRP levels < 1 mg/L) with ORs of 2.16 for OAB defined as any report of urgency and 2.06 for OAB defined as urgency with frequency.

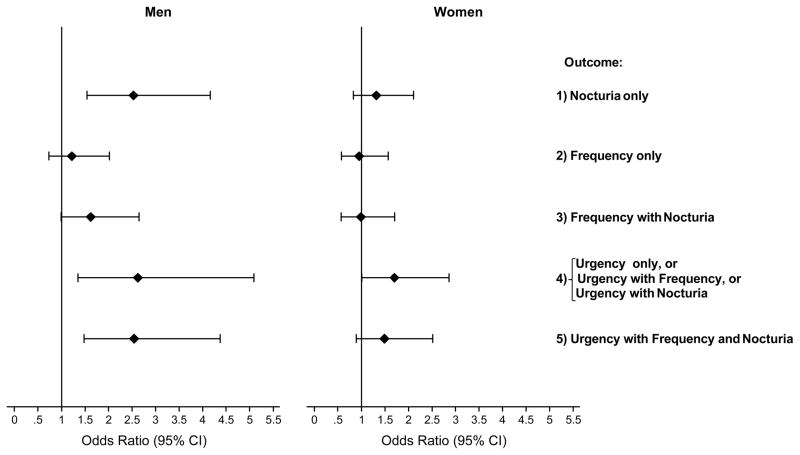

Further analyses were conducted to determine differences in the association of CRP levels with individual OAB symptoms (urgency, frequency and nocturia) and their overlap. Categories of urgency only, urgency with frequency, and urgency with nocturia were collapsed because of small numbers in individual categories. CRP levels were associated with both nocturia and urgency but not frequency in men, whereas in women CRP levels were associated with urgency only (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Association of log10 transformed C-reactive protein (CRP; mg/L) levels with urgency, frequency, nocturia and the overlap categories compared with the no-symptom group (no urgency, frequency or nocturia). Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for continuous log10(CRP) are shown. ORs for men adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), diabetes and depressive symptoms. ORs for women adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, BMI, heart disease, depressive symptoms and lower urinary tract symptom medications use.

DISCUSSION

Results of the BACH study show an association between CRP levels and OAB and support our previous finding focusing on the association of CRP levels and LUTS defined using the AUA-SI [9]. In the present analysis, we considered a broader definition of urgency, frequency and nocturia based on multiple questions on each symptom rather than the single question in the AUA-SI. Additionally, the overlap of urgency, frequency, and nocturia and its impact on the association of CRP and OAB was investigated and showed substantial overlap of these three symptoms with a low prevalence of urgency alone (Fig. 2). Levels of CRP were associated with both urgency and nocturia in men whereas in women an association was observed with urgency only.

Few epidemiological studies have investigated the role of inflammation in LUTS. Data from Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in men ≥ 60 years showed a non-significant increase in the odds of reporting three or more of the four assessed symptoms for men with detectable CRP levels [7]. However, urgency was not one the four symptoms assessed (incomplete emptying, weak stream, hesitancy and nocturia) and association of CRP levels with specific symptoms was not reported. Additionally, the more variable general CRP test was used instead of high-sensitivity CRP. Longitudinal data from the Olmsted County Study, conducted in men ≥ 40 years, have shown elevated baseline CRP levels to be associated with increase in storage LUTS scores (based on urgency, frequency and nocturia) but not for voiding LUTS (based on incomplete emptying, hesitancy, weak stream and straining) [8]. Results from the present study show CRP to be associated with two of the three storage symptoms (urgency and nocturia) in men and only with urgency in women. These results suggest that underlying inflammation in lower urinary tract in OAB manifests to different degrees in the three cardinal symptoms of OAB and seems to be responsible to a greater extent for the symptom of urgency compared with other symptoms.

Increasing evidence suggests a role of chronic inflammation in the pathogenesis and progression of BPH [10,21–23]. Inflammation detected in prostate biopsies is a common histological finding in patients with BPH [10,12]. Data from the MTOPS study has shown inflammation in prostate biopsies at baseline to be predictive of symptom progression and adverse outcomes such as acute urinary retention and need for surgery in placebo-treated patients [24]. Similar results were reported in a smaller study of men undergoing TURP [25]. Baseline data from the REDUCE trial show a relatively weak but significant correlation between the degree of inflammation and LUTS assessed by the IPSS. Chronic inflammation was associated with both storage and voiding subscores of the IPSS [11]. Longitudinal data from the Olmsted County Study have shown an inverse relationship of NSAID use in men and onset of moderate/severe LUTS and with the storage and voiding subscores of the AUA-SI [26].

However, cross-sectional analyses from the BACH study did not find an association of NSAID use and LUTS either in men or in women [27]. Although increasing evidence suggests a role of inflammation in the development of BPH and urinary symptoms in men, whether the underlying mechanism is through outlet obstruction or bladder function has not been established. Data on the inflammation and LUTS association in women is sparse, but a few studies have reported an association between inflammation and LUTS in women. Data from the BACH study showing a significant association of CRP levels with LUTS are to date the only population-based data on inflammation and LUTS in women [9]. Small clinical investigations including women have also suggested a potential role of inflammation in OAB in women [28–30]. Results of the present analysis support the hypothesis of a potential role of inflammation in the development of OAB in both men and women.

Strengths of the BACH study include a community-based random sample across a wide age range (30–79 years), inclusion of large numbers of minority participants representative of black and Hispanic populations, and a wide range of available covariates. Although history of comorbid conditions was assessed by self-report with the potential for reporting and/or recall bias, previous research has showed the reliability and validity of self-report for heart disease, diabetes and hypertension [31]. The BACH study was limited geographically to the Boston area. However, comparison of sociodemographic and health-related variables from BACH with other large regional (Boston Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System) and national (National Health Interview Survey) surveys has shown that BACH estimates are comparable to national trends on key health-related variables.

In summary, our results show increased risk of OAB with elevated levels of CRP in both men and women. The magnitude of this association was larger in men than in women. The results provide further data to add to the accumulating evidence supporting a role of inflammation in the development and progression of OAB. Further longitudinal investigations are warranted, especially among women, to better characterize the role of inflammation and inform the development of intervention studies of anti-inflammatory agents in the treatment of OAB.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) DK 56842. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases or the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- OAB

overactive bladder

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- BACH

Boston Area Community Health

- AUA-SI

American Urological Association Symptom Index

- OR

odds ratio

References

- 1.Irwin DE, Milsom I, Hunskaar S, et al. Population-based survey of urinary incontinence, overactive bladder, and other lower urinary tract symptoms in five countries: results of the EPIC study. Eur Urol. 2006;50:1306–14. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.09.019. discussion 14–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Milsom I, Abrams P, Cardozo L, Roberts RG, Thuroff J, Wein AJ. How widespread are the symptoms of an overactive bladder and how are they managed? A population-based prevalence study. BJU Int. 2001;87:760–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.02228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stewart WF, Van Rooyen JB, Cundiff GW, et al. Prevalence and burden of overactive bladder in the United States. World J Urol. 2003;20:327–36. doi: 10.1007/s00345-002-0301-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cisternas MG, Foreman AJ, Marshall TS, Runken MC, Kobashi KC, Seifeldin R. Estimating the prevalence and economic burden of overactive bladder among Medicare beneficiaries prior to Medicare Part D coverage. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25:911–19. doi: 10.1185/03007990902791025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Odeyemi IA, Dakin HA, O’Donnell RA, Warner J, Jacobs A, Dasgupta P. Epidemiology, prescribing patterns and resource use associated with overactive bladder in UK primary care. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60:949–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.01057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Irwin DE, Mungapen L, Milsom I, Kopp Z, Reeves P, Kelleher C. The economic impact of overactive bladder syndrome in six Western countries. BJU Int. 2009;103:202–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rohrmann S, De Marzo AM, Smit E, Giovannucci E, Platz EA. Serum C-reactive protein concentration and lower urinary tract symptoms in older men in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) Prostate. 2005;62:27–33. doi: 10.1002/pros.20110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.St Sauver JL, Sarma AV, Jacobson DJ, et al. Associations between C-reactive protein and benign prostatic hyperplasia/lower urinary tract symptom outcomes in a population-based cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:1281–90. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kupelian V, McVary KT, Barry MJ, et al. Association of C-reactive protein and lower urinary tract symptoms in men and women: results from Boston Area Community Health survey. Urology. 2009;73:950–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nickel JC, Downey J, Young I, Boag S. Asymptomatic inflammation and/or infection in benign prostatic hyperplasia. BJU Int. 1999;84:976–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.00352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nickel JC, Roehrborn CG, O’Leary MP, Bostwick DG, Somerville MC, Rittmaster RS. The relationship between prostate inflammation and lower urinary tract symptoms: examination of baseline data from the REDUCE trial. Eur Urol. 2008;54:1379–84. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Silverio F, Gentile V, De Matteis A, et al. Distribution of inflammation, pre-malignant lesions, incidental carcinoma in histologically confirmed benign prostatic hyperplasia: a retrospective analysis. Eur Urol. 2003;43:164–75. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(02)00548-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKinlay JB, Link CL. Measuring the urologic iceberg: design and implementation of the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. Eur Urol. 2007;52:389–96. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of terminology in lower urinary tract function: report from the standardisation sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Urology. 2003;61:37–49. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)02243-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Washburn RA, Smith KW, Jette AM, Janney CA. The Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE): development and evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:153–62. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Green LW. Manual for scoring socioeconomic status for research on health behavior. Public Health Rep. 1970;85:815–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turvey CL, Wallace RB, Herzog R. A revised CES-D measure of depressive symptoms and a DSM-based measure of major depressive episodes in the elderly. Int Psychogeriatr. 1999;11:139–48. doi: 10.1017/s1041610299005694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ridker PM. C-reactive protein and the prediction of cardiovascular events among those at intermediate risk: moving an inflammatory hypothesis toward consensus. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:2129–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schafer J. Analysis of incomplete multivariate data. London: Chapman and Hall; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cochran W. Sampling Techniques. 3. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kramer G, Marberger M. Could inflammation be a key component in the progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia? Curr Opin Urol. 2006;16:25–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sciarra A, Di Silverio F, Salciccia S, Autran Gomez AM, Gentilucci A, Gentile V. Inflammation and chronic prostatic diseases: evidence for a link? Eur Urol. 2007;52:964–72. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kramer G, Mitteregger D, Marberger M. Is benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) an immune inflammatory disease? Eur Urol. 2007;51:1202–16. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roehrborn CG, Kaplan SA, Noble WD. The impact of acute or chronic inflammation in baseline biopsy on the risk of clinical progression of BPH: results from the MTOPS study. J Urol. 2005;173:346. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mishra VC, Allen DJ, Nicolaou C, et al. Does intraprostatic inflammation have a role in the pathogenesis and progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia? BJU Int. 2007;100:327–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.06910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.St Sauver JL, Jacobson DJ, McGree ME, Lieber MM, Jacobsen SJ. Protective association between nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug use and measures of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:760–8. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gates MA, Hall SA, Chiu GR, et al. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug use and lower urinary tract symptoms: results from the Boston Area Community Health Survey. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:1022–31. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tyagi P, Barclay D, Zamora R, et al. Urine cytokines suggest an inflammatory response in the overactive bladder: a pilot study. Int Urol Nephrol. 2010;42:629–35. doi: 10.1007/s11255-009-9647-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Comperat E, Reitz A, Delcourt A, Capron F, Denys P, Chartier-Kastler E. Histologic features in the urinary bladder wall affected from neurogenic overactivity – a comparison of inflammation, oedema and fibrosis with and without injection of botulinum toxin type A. Eur Urol. 2006;50:1058–64. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Apostolidis A, Dasgupta P, Denys P, et al. Recommendations on the use of botulinum toxin in the treatment of lower urinary tract disorders and pelvic floor dysfunctions: a European consensus report. Eur Urol. 2009;55:100–19. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okura Y, Urban LH, Mahoney DW, Jacobsen SJ, Rodeheffer RJ. Agreement between self-report questionnaires and medical record data was substantial for diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction and stroke but not for heart failure. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:1096–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]