Abstract

Purpose

We report our experience and literature review concerning surgical treatment of neurological burst fractures of the fifth lumbar vertebra.

Materials and methods

Nineteen patients with L5 neurological burst fractures were consecutively enrolled; 6 patients had complete motor deficits, and 12 had sphincter dysfunction. We performed 18 posterior and one combined approaches. To avoid kyphosis, posterior internal fixation was achieved by positioning patients on the operating table with hips and knees fully extended. At the latest follow-up (mean 22 months, range 10–66), neurological recovery, canal remodeling and L4–S1 angle were evaluated.

Results

Vertebral body replacement was difficult, which therefore resulted in an oblique position of the cage. Vertebral bodies still remained deformed, even though fixation allowed for an acceptable profile (22°, range 20–35). We observed three cases of paralysis, five complete, and three incomplete recoveries. In the remaining eight patients, sphincter impairment was the only finding. In 15 patients, pain was absent or occasional; in four individuals, it was continuous but not invalidating. Remodeling was visible by X-ray and/or CT, without significant secondary stenosis.

Conclusions

The L5 burst fractures are rare and mostly due to axial compression. Cauda and/or nerve root injuries are absolute indications for surgery. If an anterior approach is technically difficult, laminectomy can allow for decompression, and it can be easily combined with transpedicular screw fixation. Posterior instrumented fusion, also performed with the aim to restore sagittal profile, when associated with an accurate spinal canal exploration and decompression, may be looked at as an optimal treatment for neurological L5 burst fractures.

Keywords: Burst fracture, Low lumbar spine, Neurologic deficit, Internal fixation, Lordosis

Introduction

Fractures of the fifth lumbar vertebra are quite uncommon, representing only 1.2% of overall spine fractures and 2.2% of thoracolumbar fractures [1]. Very little has been written [2–5] and some of the published papers include either L3 and L4 fractures [6–8] or patients with no neurological impairment undergoing conservative treatment [9–12]. Burst or compression fractures type A in Magerl classification [13] are more frequently found, whilst flexion–distraction fractures (type B) and fractures with rotation/dislocation (type C) are uncommon [14]. Our case series include patients with burst fractures type A3.1 or A3.3, affected by peripheral motor impairment and sphincter deficits due to retropulsion of bony and/or disc fragments. Early decompression is mandatory when neurological impairment arises, whereas post-traumatic instability requires lumbosacral fixation [4, 15].

Materials and methods

We enrolled 19 consecutive patients with L5 neurological fractures since 1999 to 2008 (14 males, 5 females; mean age 35, range 22–50). Of them, 3 were affected by type A3.1 fractures and 16 presented with type A3.3 fractures. All but one patient underwent laminoarthrectomy, pedicle fixation, and posterolateral fusion. The only exception was an A3.3 highly comminuted fracture treated by circumferential approach. The dislocated bony fragment was impacted towards the vertebral body in 11 patients, whereas it was removed by anterior approach in one patient. Disc herniation was found in three patients, whilst four patients had dural tears. One patient had an associated L4 burst fracture and another one a stable L1 fracture. Peripheral motor impairment, involving feet and ankles, was found in all patients, with 6 presenting with severe impairment (score of 0 or 1) and 13 with moderate symptoms (score 2) (Table 1). Twelve patients had sphincter impairment, marked (score 1) in eight cases or moderate (score 2) in four. Operating table position included extended hips and knees, in order to obtain reduction of kyphosis and achieving a lordotic fixation. Post-operative and follow-up (mean 22 months, range 10–66) evaluation included neurological improvement, pain [7], canal remodeling [17] and L4–S1 angle measurement [1].

Table 1.

Japanese Orthopaedic Association functional assessment scale [16], modified for lower extremities (feet and ankles) and sphincter dysfunction

| Motor dysfunction score of the lower extremities | |

| Complete loss of motor and sensory function | 0 |

| Sensory preservation without ability to move | 1 |

| Able to move but unable to walk | 2 |

| Able to walk on flat floor with a walking aid | 3 |

| Able to walk up and/or down stairs with handrail | 4 |

| Moderate to significant lack of stability | 5 |

| Mild lack of stability | 6 |

| No dysfunction | 7 |

| Sphincter dysfunction score | |

| Inability to micturate voluntarily | 0 |

| Marked difficulty with micturition | 1 |

| Mild to moderate difficulty with micturition | 2 |

| Normal micturition | 3 |

Results

No major complications were associated with operative technique or construct failure. Cage positioning, in the only patient with a circumferential approach, was difficult due to a narrow operative field. That resulted in an oblique positioning of the titanium cage. At follow-up evaluation, vertebral bodies remained deformed due to height loss, though rod contouring allowed an acceptable final lumbar profile (L4–S1 angle mean 22°, range 20–35) (Fig. 1a–e). In five patients (26%), complete neurological recovery was observed (score 7), whereas in three (15%), some distal impairment (score from 3 to 5) was still appreciable (three of them had associated marked sphincter deficits). Three patients (15%) were finally paralyzed (score 0 or 1). The remaining eight patients (43%) had isolated, mild or moderate sphincter impairment. Fifteen individuals (79%) had no or intermittent pain (score of 0 or 1), whilst four patients (21%) had continuous but not invalidating pain (score of 3). Canal remodeling was a common finding in CT and X-ray studies, with no secondary stenosis (Fig. 2a–c).

Fig. 1.

L5 fracture in a 61-year-old woman. a, b axial and sagittal CT reconstruction that shows an A3.3 burst fracture, c MRI shows neural compression, d post-operative CT at 1 year follow-up shows bone healing and residual deformity of the vertebral body, e axial-loading CT that shows a good sagittal profile (L4–S1 angle >30°)

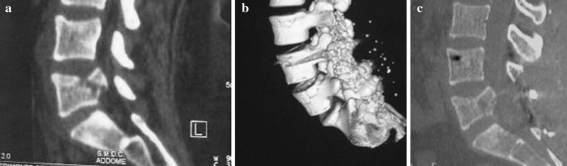

Fig. 2.

a CT scan (sagittal reconstruction) shows the dislocated bony fragment with compression of the cauda equina, b CT three-dimensional reconstruction shows L4–S1 fixation, fracture reduction, and posterior fusion, c CT scan (sagittal reconstruction) demonstrates fracture healing and spinal canal remodeling at 1 year follow-up. Patient had residual sphincter dysfunction with score 2 (moderate)

Discussion

The L5 fractures are most frequently due to axial compression forces [18]. Comminution of the vertebral body may be significant in type A3.1 and most of all in type A3.3 fractures. This may lead in turn to disc herniation and/or degeneration, and either bony or disc fragments may determine narrowing of the spinal canal. When no neurological impairment was seen, conservative treatment including bracing and rest yielded satisfactory results in several series [7, 8]. By contrast, compression of neural tissue associated with complete motor impairment is mandatory for laminectomy and/or arthrectomy, the last depending on whether facet dislocation is present [7, 19]. Posterior decompression is easily associated with pedicular screw fixation, and transpedicular bone implantation is also possible [3]. Anterior interbody expansion cage via posterolateral approach may also be an option [4]. In our experience, the great majority of patients were treated by L4–S1 instrumentation, and only one needed L3 fixation due to a concomitant L4 fracture. When intact pedicles were found at L5, short transpedicular screws can be used at the aforementioned level. We always aimed at lordotic contouring of the instrumentation, as many authors [12, 20] reported better results when spino-pelvic profile was unmodified. Rod contouring, together with definitive fixation performed with extended hips and knees, seems to help in preventing kyphosis and sacral verticalization.

Migrated bony fragment may be either impacted or removed, whereas chances for ligamentotaxis are considered to be limited [5]. Most often, we performed fragment impaction, as we think it allows complete canal decompression. Another issue includes the role of impaction on preventing post-traumatic modifications in load-sharing forces, which are mostly exerted on the posterior half of the vertebral body [7, 8].

The anterior approach may be an option when decompression and/or reconstruction is needed, and somatectomy may be performed in association with a cage body replacement as it is performed at the thoracolumbar junction [21]. Nevertheless, lumbosacral anterior approach may be difficult due to major vessels (sometimes adherent to the injured vertebra) and lack of specific L4–S1 instrumentations [22]. Corpectomy and lateral plating across the lordotic segments can be technically demanding [8]. In our series, only one patient has been treated with an anterior approach. Pitfalls in this surgery were a narrow operative field, which yielded to oblique positioning of the cage with respect to L4–S1 endplates. Follow-up X-rays showed no loosening of the cage, though.

We had three patients with minimal or no bony retropulsion, whereas extruded and migrated disc encroached on cauda and spinal nerve roots. Two dural tears were also found to be associated. We removed disc tissue and sutured dural tears. Clinical evaluation at follow-up showed complete neurological recovery.

Initial neurological condition may influence clinical outcomes of surgical strategy [23]. Therefore, the same technique performed at the same time in patients with different neurological status may lead to different outcomes. Moreover, in our series even with complete recovery of distal motor deficits, residual sphincter impairment has been encountered.

Disc degeneration, endplate deformity, and acquired stenosis may be possible causes of late pain, whilst in our study they were not such an issue. In our opinion, these late complications may be prevented by a sound fusion, wide decompression, and restoration of the lumbosacral lordosis.

Conclusions

The present study lacks a long-term follow-up. Nevertheless, canal remodeling is a well-known process which, in association with a sound and correctly aligned posterior stabilization, makes it suitable for treatment of L5 neurological burst fractures. Operating table position included extended hips and knees, can be useful to achieve a good recovery of the lumbar lordosis. In our experience, residual sphincter dysfunctions, from marked to mild, were the major neurological sequelae in this type of spinal injuries. We recommend an accurate spinal canal exploration with the aim of reducing retropulsion of bone fragments and/or remove any disc herniation.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Finn CA, Stauffer ES. Burst fracture of the fifth lumbar vertebra. J Bone Joint Surg. 1992;74A:398–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mick CA, Carl A, Sacks B, et al. Burst fracture of the fifth lumbar vertebra. Spine. 1993;13:1878–1884. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199310000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaminski A, Muller EJ, Muhr G. Burst fracture of the fifth lumbar vertebra: results of posterior internal fixation and transpedicular bone grafting. Eur Spine J. 2002;11(5):435–440. doi: 10.1007/s00586-002-0390-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kocis J, Wendsche P, Visna P. Complete burst fracture of the fifth lumbar vertebra treated by posterior surgery using expandable cage. Acta Neurochir. 2008;150(12):1301–1305. doi: 10.1007/s00701-008-0149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sebesta P, Stulik J, Viskocil T, Kryl J. Posterior stabilization of L5 burst fractures without reconstruction of the anterior column. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech. 2008;75(2):123–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.An HS, Simpson JM, Ebraheim NA, et al. Low lumbar burst fractures: comparison between conservative and surgical treatment. Orthopedics. 1992;15:367–373. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19920301-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andreychik DA, Alander DH, Senica KM, Stauffer ES. Burst fractures of the second through fifth lumbar vertebrae. J Bone Joint Surg. 1996;78A:1156–1166. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199608000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seybold EA, Sweeney CA, Fredrickson BE, et al. Functional outcome of low lumbar burst fractures. Spine. 1999;24:2154–2161. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199910150-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fredrickson BE, Yuan HA, Miller H. Burst fracture of the fifth lumbar vertebra. J Bone Joint Surg. 1982;64A:1088–1094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Court-Brown CW, Gertzbein SD. The management of burst fractures of the fifth lumbar vertebrae. Spine. 1987;12:308–312. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198704000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blanco JF, Pedro JA, Hernandez PJ, et al. Conservative management of burst fractures of the fifth lumbar vertebra. J Spinal Disord. 2005;18(3):229–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Butler JS, Fitzpatrick P, Ni Mhaolain AM, et al. The management and functional outcome of isolated burst fracture of the fifth lumbar vertebra. Spine. 2007;32(4):443–447. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000255076.45825.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magerl F, Aebi M, Gertzbein SD, et al. A comprehensive classification of thoracic and lumbar incurie. Eur Spine J. 1994;3(4):184–201. doi: 10.1007/BF02221591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aihara T, Takahashi K, Yamagata M, et al. Fracture dislocation of the fifth lumbar vertebra. A new classification. J Bone Joint Surg. 1998;80B:840–845. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.80B5.8657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.An HS, Vaccaro A, Cotler JM, Lin S. Low lumbar burst fracture. Comparison among body cast, Harrington rod, Luque rod and Steffee plate. Spine. 1991;16(Suppl 8):S440–S444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benzel EC, Lancon J, Kesterson L, Hadden T. Cervical laminectomy and dentate ligament section for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. J Spinal Disord. 1991;4:286–295. doi: 10.1097/00002517-199109000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dai LY. Remodeling of the spinal canal after thoracolumbar burst fracture. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;382:119–123. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200101000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robertson PA. http://www.spineuniverse.com/professional/pathology/trauma/fractures-l4-l5-low-lumbar-fractures

- 19.Huang T, Chen J, Hsu RW. Burst fracture of the fifth lumbar vertebra with unilateral facet dislocation: case report. J Trauma. 1994;36(5):755–757. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199405000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dai LD. Low lumbar spinal fractures: management options. Injury. 2002;33(7):579–582. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(02)00021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oprel PP, Tuinebreijer WE, Patka P, Hartog D. Combined anterior–posterior surgery versus posterior surgery for thoracolumbar burst fractures: a systematic review of the literature. Open Orthop J. 2010;4:93–100. doi: 10.2174/1874325001004010093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khare GN, Kockhar VL, Lal Y. Chance’s fracture of the fourth lumbar vertebra. Injury. 1989;20(5):303–304. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(89)90177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramieri A, Domenicucci M, Ciappetta P, et al. Spine surgery in neurological lesions of the cervico-thoracic junction. Eur Spine J. 2011;20(Suppl 1):S13–S19. doi: 10.1007/s00586-011-1748-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]