Abstract

In the skin of fire-bellied toads (Bombina species), an aminoacyl-l/d-isomerase activity is present which catalyses the post-translational isomerization of the l- to the d-form of the second residue of its substrate peptides. Previously, this new type of enzyme was studied in some detail and genes potentially coding for similar polypeptides were found to exist in several vertebrate species including man. Here, we present our studies to the substrate specificity of this isomerase using fluorescence-labeled variants of the natural substrate bombinin H with different amino acids at positions 1, 2 or 3. Surprisingly, this enzyme has a rather low selectivity for residues at position 2 where the change of chirality at the alpha-carbon takes place. In contrast, a hydrophobic amino acid at position 1 and a small one at position 3 of the substrate are essential. Interestingly, some peptides containing a Phe at position 3 also were substrates. Furthermore, we investigated the role of the amino-terminus for substrate recognition. In view of the rather broad specificity of the frog isomerase, we made a databank search for potential substrates of such an enzyme. Indeed, numerous peptides of amphibia and mammals were found which fulfill the requirements determined in this study. Expression of isomerases with similar characteristics in other species can therefore be expected to catalyze the formation of peptides containing d-amino acids.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00726-011-0890-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: d-amino acid, Chirality, Post-translational modification, Peptide biosynthesis, Amphibian skin

Introduction

In higher eukaryotes, the majority of bioactive peptides are synthesized as larger precursors, which, upon transit through the secretory pathway and in immature secretory granules, are processed by endo- and exoproteolytic cleavages. Formation of the mature products often also includes a variety of additional modifications at the termini and of amino acid side chains. An intriguing and inconspicuous post-translational reaction is the change of chirality of amino acids within the peptide backbone whereby an l-amino acid is converted to the d-isomer (Jilek and Kreil 2008; Bai et al. 2009). The first animal peptides, which were found to contain a d-amino acid as the second residue were dermorphins and deltorphins, isolated from the skin of South American tree frogs. These peptides bind with high affinity to μ- or δ-opiate receptors (Kreil et al. 1989; Montecucchi et al. 1981; Mor et al. 1989). Additional examples of peptides containing a d-amino acid as the second residue are the bombinins H, peptides with antibacterial and hemolytic properties (Mignogna et al. 1993), from the skin of Bombina species and, recently two components, a natriuretic peptide and a β-defensin, from the venom of the male platypus (Torres et al. 2005). While to date the d-amino acid in all vertebrate peptides is present at position 2 of the mature product, it has also been found in other positions in peptides from invertebrates, such as mollusks, crustaceans and the venom of a spider (Kamatani et al. 1989; Ohta et al. 1991; Soyez et al. 1994, 2000; Heck et al. 1994; Buczek et al. 2005a, b, c; Ollivaux et al. 2009). As for biological activities, diverse findings have been made. These range from complete absence of activity in the all l-forms to subtle differences in folding propensities and activity of the two isomeric species (Kreil et al. 1989; Zangger et al. 2008; Mangoni et al. 2000, 2006; Montecucchi et al. 1981; Bozzi et al. 2008).

A clue about the biosynthesis of the d-form came from studies on the cloned cDNAs of the precursor polypeptides where it was observed that a codon for the l-residue is present at the position where a d-amino acid occurs in the mature form. An enzyme which catalyses the change of chirality of an amino acid in peptide linkage was first described by Heck et al. (Heck et al. 1994). In their analysis of the venom of a funnel web spider, a protein was isolated which catalyzed the partial isomerization of a serine close to the carboxyl-end of ω-agatoxin IV from the l- to the d-isomer. Such an enzyme could be named peptidyl-aminoacyl-l/d-isomerase, henceforth briefly referred to as an isomerase (Kreil 1997).

We have previously isolated an isomerase from the skin secretions of different Bombina species (B. variegate, B. bombina, B. orientalis). This yielded a 52 kDa glycoprotein, which converted, in a model peptide corresponding to the amino-terminus of bombinin H, the l-isoleucine at the second position to d-allo-isoleucine (Jilek et al. 2005). In a search in the data banks, genes coding for proteins related to the frog enzyme were found in several vertebrate species. In particular, the amino-terminal domain H of the human IgG-Fcγ binding protein (Harada et al. 1997) is related to the frog skin enzyme and thus could have isomerase activity. Interestingly, an isomerase has also been isolated from the venom of male platypus (Torres et al. 2007, 2006), but it is not yet known whether this protein is related to the enzyme from Bombina skin. Moreover, recent results make it likely that isomerase activity is present in mouse heart (Koh et al. 2010).

We have now tested a variety of peptides as possible substrates of the frog skin isomerase; the use of short peptides is a common and successful approach to purify isomerases and study their substrate specificities (Heck et al. 1996; Jilek et al. 2005; Bansal et al. 2008). The enzyme has a rather broad specificity, particularly with respect to the amino acid in position 2. A search in the databanks has shown that many potential substrates for such an isomerase are present in the skin secretions of other frogs as well as in mammalian cells.

Methods

Enzyme preparation

Skin secretion was collected from B. orientalis and processed as described (Jilek et al. 2005). Briefly, the glycoprotein fraction eluted from ConA-Sepharose with methylmannoside was passed over a Sephacryl S-300 column (20 mM Hepes buffer, pH 7.6, containing 1 mM EDTA). The fractions with isomerase activity were concentrated, re-chromatographed under the same conditions, and subsequently passed over SP-Sepharose. The flow-through was adjusted to pH 8.6 and fractionated over Q-Sepharose. The enzyme could be eluted with a gradient of 1–2.5 mM NaCl. Active fractions were concentrated with Centricon filters retaining proteins with a mass of 30–100 kDa were once more chromatographed over SP- and Q-Sepharose. Cuts from the main peak were again carried through the same ion-exchange protocol. Every single fraction was then tested for enzymatic activity and the protein’s molecular weight determined by SDS-PAGE. Highest enzymatic activity coincided with an apparently homogeneous protein of 52 kDa molecular mass.

Peptide synthesis

Peptides were obtained from PSL (Heidelberg, Germany). Briefly, peptides were synthesized on a continuous flow synthesizer using Fmoc solid phase chemistry (Rink Amide AM resin (200–400 mesh, 0.62 meq/g) (Nova-Biochem, Germany) with PyBOP as condensation reagent and N-methylmorpholine as a base. PheLac (Sigma, Germany) was subjected to the acylation reaction without a protecting group. Peptides containing a Cys were coupled via the SH-group to the fluorophor Bodipy FL IA [(4,4-difluoro-5,7-dimethyl-4-bora-3′,4′-adiaza-S-indacene-3-propionyl)-N-iodoacetylethylenediamine1; Invitrogen]. Peptides were purified by reverse-phase HPLC over a C18 column (Phenomenex or Vydac) with a linear gradient of acetonitrile (solvent A, 0.1% TFA; solvent B, 80% acetonitrile) and their mass was determined by MALDI MS.

Enzyme assay

Peptides at a 4 μM concentration (unless otherwise stated) were incubated at 37°C with aliquots of the enzyme at pH 6.5 in 50 mM phosphate buffer containing 5 mM EDTA. At different times, aliquots of the reaction mixture were removed and injected onto a 218TP C-18 column (Vydac, Hesperia, CA, USA). Substrates and reaction products were eluted with a linear gradient of acetonitrile (solvent A, 0.1% TFA; solvent B, 80% acetonitrile). In case of the peptide with Glu at position 2, 50 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7.0 was chosen as solvent A, because of better peak resolution than at pH 2. Unlabeled peptides were detected by UV absorbance at 214 nm. Fluorescence emission of the labeled peptides was recorded at 514 nm (excitation at 480 nm). Peaks were integrated with Beckman System Gold Software. In all instances, we have also tested the diastereomeric peptide with respect to its elution time from the HPLC column. Isomerization of peptides with Gln, Lys, Asp or Glu in position 2 yielded products with decreased hydrophobicity. For these peptides, the d → l reaction rates were determined. These must be corrected by the respective equilibrium constant in order to be properly compared with the l → d reaction rates. Using this protocol, possible misinterpretations due to N-terminally truncated fragments produced in the course of the reaction could be avoided.

Data base search

A subset of the protein sequence compilation containing amphibian, bovine or human sequences was downloaded in GenPept format from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/ (Benson et al. 2008). Entries with the notes ‘processed active peptide’ or ‘mature chain’ in the respective ‘region’ section were included. The N-terminal tripeptide sequences thus obtained were compared with the isomerase consensus (Ile, Leu, Phe, Glu, Lys, Tyr, Trp)1-Xaa2-(Gly, Ala, Asn, Phe)3. Met in position 1 was excluded from the search because of the expected high number of false positives.

Results and discussion

Here we present results on the substrate specificity of an isomerase from skin secretions of B. orientalis. As standard substrate in a discontinuous RP-HPLC-based assay, we used the peptide Ile-Ile-Gly-Pro-Val-Leu-Cys-amide, which corresponds to the first six residues of bombinin H plus a cysteine residue. The fluorophor Bodipy was added to the SH-group of the cysteine thereby yielding a highly fluorescent derivative. In this assay, the isomerization product could be detected in minute quantities, even in the presence of a large excess of the all-l-substrate (details are described in "Methods"). Due to its sensitivity, the assay could be performed at physiologically relevant substrate concentrations well below enzyme saturation (Fig. S1). Moreover, the fluorophore clearly marks derivatives of the substrate, whereas N-terminal fragments or components of the enzyme preparation remain undetected.

We then tested a series of similar peptides with different amino acids in position 2, as well as in position 1 and 3. These results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Isomerization rate of different substrates relative to the amino-terminal sequence of bombinin H. Rates with different amino acids at position 2 (A), 1 (B) and 3 (C) are shown. D: Mammalian peptides tested

| Reaction rates | Equilibrium constant | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute (μM h−1) | Relative (%) | |||

| (A) | IIGPVLĊa | 110 | 100 | 1.1 |

| Fg | 1,220 | 1,100 | 0.59 | |

| M | 1,170 | 1,100 | 1.44 | |

| F | 1,060 | 1,000 | 2.85 | |

| Nl | 1,000 | 900 | 1.33 | |

| L | 240 | 222 | ||

| W | 135 | 130 | 1.86 | |

| Ċ | 78 | 70 | 0.66 | |

| A | 24 | 22 | ||

| D | 19° | 17 | 1.32 | |

| K | 13° | 12 | 1.28 | |

| Q | 10° | 9 | 0.7 | |

| T | 9 | 8 | 0.66 | |

| E | <4° | <3° | ||

| (B) | IIGPVLĊa | 110 | 100 | |

| F | 187 | 170 | ||

| W | 140 | 130 | ||

| E | 6.5 | 4 | ||

| Y | 1.5 | 1 | ||

| A | <0.4 | <1 | ||

| KIA | 2.5 | <3 | ||

| SIA | N.d. | – | ||

| GIA | N.d. | – | ||

| (C) | IIGPVLĊa | 110 | 100 | |

| F | 8 | 3.5 | ||

| A | 7 | 3.3 | ||

| D | 0.1 | <0.2 | ||

| K | N.d. | – | ||

| Q | N.d. | – | ||

| IFF | 116 | 107 | ||

| IĊF | 5 | 1.2 | ||

| (D) | IIGPVLĊa | ++ | ||

| IMFFEMĊaa | +++ | |||

| LLGDFFĊab | ++ | |||

| FVNQHLac | + | |||

| FLFQPQRFad | +++ | |||

Fg phenylglycine, Nl norleucine, Ċ Cys with Bodipy attached via thioether linkage; n.d. not detectable (below 0.05 μM h−1)

a DLP-2/4(1–6)

b LL-37(1–6)

c Insulin B-chain (1–6)

d Neuropeptide FF (full length)

° Uncorrected reaction rates

Effect of single amino acid substitutions within the model substrate

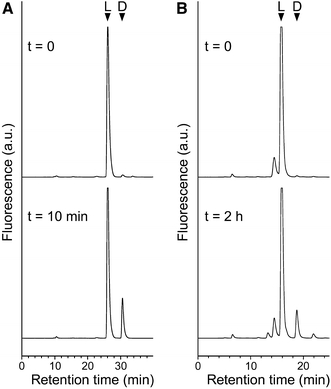

Compared to Ile in position 2, five other amino acids react about ten times faster in the isomerization reaction, namely methionine, phenylalanine, leucine, norleucine (Nle) and phenylglycine (Phg). In addition, the peptide with tryptophan in position 2 is a good substrate. Several peptides with other amino acids at this position are also accepted by the isomerase with relative reaction rates of 10–30%. These include a cysteine derivatized with the fluorophor Bodipy (Cs*). It is surprising that a residue with a rather bulky side chain is still a good substrate in the isomerization reaction (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Isomerization reaction demonstrated for substrates with unnatural amino acids at the second position. RP–HPLC chromatograms of reaction mixtures of labeled (a) Ile-Phg-Gly and (b) Ile-Cs*-Gly model peptides after the indicated incubation time

The peptide with Glu at position 2 was isomerised at a low reaction rate, which was only about 1/50 of that of Asp-2. This fact could be explained by an interference of the side chain carboxy group with the catalytic bases of the enzyme. The γ-carboxy group of free Glu has indeed been described to be capable of forming a six-membered ring with the α-carbon (Smith and Reddy 2002).

We also tested peptides with different amino acids in position 1. Besides Ile only the ones with Leu, Phe or Trp were found to be good substrates.

When substituting residue one of the model peptide with a hydrophilic amino acid, it was necessary to concomitantly replace the achiral Gly-3 by an alanine (see Table 1B) in order to re-establish the neighborhood-effect, which is a prerequisite for the chromatographic separation of the diastereomers by RP–HPLC (Kovacs et al. 2006).

Exchanging the Gly in position 3 with amino acids with bulkier side chains yielded only relatively poor substrates. However, in spite of the large difference in the size, Phe in position 3 was comparable to that of Ala.

We earlier tested several peptides derived of dermorphins and deltorphins (Amiche et al. 1998; Lazarus et al. 1999; Negri et al. 2000). These were, however, unstable and apparently degraded by traces of proteases present in the enzyme preparation (Jilek et al. 2005). A chimeric peptide with the N-terminal tripeptide sequence of a deltorphin (Wechselberger et al. 1998) and the rest from the standard peptide was sufficiently stable for the assay and was observed to be a substrate (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Isomerization reaction demonstrated for various substrates. RP–HPLC chromatograms of reaction mixtures of (a) a chimeric peptide with the amino terminal sequence Tyr-Met-Phe of a deltorphin and the rest from the standard peptide, (b) a truncated peptide derived from the β-defensin-like peptide; (c) B-chain of mammalian insulin and (d) neuropeptide FF. In panels C,D peptides without a fluorescent marker (200 μM each) were used

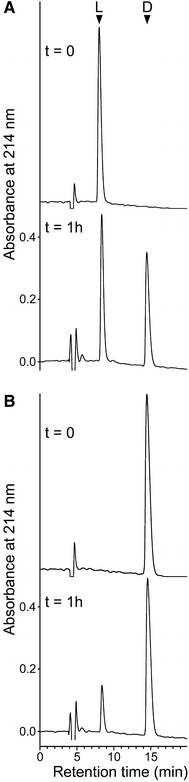

The enzymatic isomerization reaction proceeds in both directions (Fig. 3). Interestingly, the equilibrium constants K which, in kinetic terms, are equal to the quotient of the respective forth and back reaction velocities (Haldane 1930), range from 2.85 for Phe-2 to 0.59 for Phg-2 (Fig. S2; Table 1), whereas it is close to 1 for the standard substrate. This preference for a reaction, either from l to d or vice versa, in different substrates is puzzling.

Fig. 3.

The isomerization reaction proceeds in both directions. RP–HPLC chromatograms of reaction mixtures of (a) Ile-Phe-Gly peptide or (b) Ile-(D-Phe)-Gly peptide are shown (arrows). Peptides without a fluorescent marker (250 μM each) were used

The role of the amino-terminus

The frog isomerase acts exclusively on the second amino acid, while the substrate spectrum of the enzyme is largely defined by residues 1 and 3. After replacing the α-amino with a hydroxyl group, as in the peptide with phenyllactic acid instead of phenylalanine at position 1, the isomerization reaction decreased by several orders of magnitude and could barely be detected (see Fig. S3). Peptides with an acetylated amino group are not substrates. As in the case of amino- and dipeptidylaminopeptidases, a free, positively charged α-amino group is important for substrates of the frog skin isomerase. In contrast, in the case of the spider isomerase the site of stereoconversion is defined by the location of the consensus Leu-Ser-Phe-Ala within the sequence rather than by its distance from the COOH-terminus (Heck et al. 1996). This indicates that substrate recognition is basically different in this enzyme.

Search for potential substrates from other amphibia and vertebrates

Numerous amphibian peptides, which match the tripeptide-consensus (Ile, Leu, Phe, Glu, Lys, Tyr, Trp)-Xaa-(Gly, Ala, Asn, Phe), could be identified in the NIH protein sequence compilation (Table S1). For example, from various Bombina species, peptides related to bombinin H have been characterized (Simmaco et al. 2009; Lai et al. 2002). Moreover, a similar peptide was recently isolated from another frog species, namely alyteserin-2 from the midwife toad Alytes obstetricans (Conlon et al. 2009). In this search, additional peptides were retrieved, namely several ranalexins, temporins 1DYa and PTa and brevenins 1PTa and 1PTb from diverse Rana species (Halverson et al. 2000; Conlon et al. 2008), hylin a1 from the spotted treefrog (Hypsiboas albopunctatus) (Castro et al. 2009) as well as kassorin S from the African hyperoliid frog (Kassina senegalensis) (Chen et al. 2010) and signiferin-2 from an Australian froglet (Crinia signifera) (Maselli et al. 2004). All of these are predicted to be good substrates for the Bombina isomerase. Another candidate is the dermaseptin-like peptide aDrs (Genbank ID: CAA06430) from the skin of Pachymedusa dacnicolor, a tree frog from southern Mexico (Wechselberger 1998). Notably, this peptide is characterized by an inherent propensity to self-assemble into amyloid fibrils in a reversible pH-controlled fashion (Gößler-Schöfberger et al. 2009).

Genes potentially coding for proteins related to the Bombina isomerase are present in mammals as well (Jilek et al. 2005). Moreover, the substrate spectrum of a recently reported isomerase activity present in the venom of male Platypus is apparently similar to that of the Bombina enzyme (Torres et al. 2006; Bansal et al. 2008). For this enzyme, it was shown that the third residue had to be a Phe and the second a non-β-branched hydrophobic residue. Indeed, the amino-terminal sequence Ile-Met-Phe of the defensin-like peptide from the platypus venom (Torres et al. 2005) was observed to be a fairly good substrate for the Bombina enzyme (see Table 1D and Fig. 2). These observations encouraged us to include peptides of mammalian origin in our search. This yielded several antimicrobial peptides such as LAP (lingual antimicrobial peptide), β-defensins 2 and 8 from cattle and the human peptide LL-37 (Schonwetter et al. 1995; Tang and Selsted 1993; Gudmundsson et al. 1996). As potential substrates for the frog isomerase we tested two mammalian peptides. One was the neuropeptide FF (Perry et al. 1997), a potent opioid antagonist and a member of the RF-amide family, to which the diastereomeric fulicin from an African snail (Ohta et al. 1991) also belongs. The other was the well-conserved insulin B chain. As shown in Fig. 2, both yielded detectable amounts of diastereomeric product.

Concluding remarks

In this communication, we present our results on the substrate specificity of the Bombina isomerase. It could be shown that in a variety of peptides with amino-terminal sequences related to the one of bombinin H, the natural substrate of this isomerase, the second residue is converted from the l- to the d-form, albeit at different rates. Using a consensus sequence derived from these results, a databank search revealed that many peptides isolated from skin secretions of different frogs would be potential substrates for such an enzyme. Moreover, in the genome of Xenopus tropicalis a gene coding for a protein closely related to the Bombina isomerase (77% similarity, 59% identity over a stretch of 407 amino acids) was found (Genbank ID: AAMC01102290) (Hellsten et al. 2010). Conversely, peptides with an amino-terminal tyrosine, as present in a variety of opioid peptides isolated from skin of Phyllomedusinae, a sub-family of tree frogs living in South and Middle America, are rather poor substrates of the Bombina enzyme. It seems likely that a different, but probably related isomerase is present in the skin of these amphibia.

Finally, an isomerase has been isolated from the venom of the male platypus (Bansal et al. 2008; Torres et al. 2006). A search in the databanks has shown that many mammalian peptides could also be substrates of this and/or the Bombina enzyme. As already mentioned, genes potentially coding for relatives of the frog isomerase are present in the genome of different mammalian and other vertebrate species (Jilek et al. 2005). If any of these genes is expressed and indeed codes for an isomerase like the Bombina enzyme, many potential substrates, such as hormones, neurotransmitters, antimicrobial peptides, etc. would be present in different cells. This raises the intriguing possibility that some of these contain, at least in trace amounts, a d-amino acid.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Austrian Science Fund FWF grants P19393 (to A.J.) and P13279 (to G.K.), by the Alois Sonnleitner Stiftung of the Austrian Academy of Sciences (to K.L. and A.J.), and by grant K-151.217/4-2007/Lin of the “Land Oberösterreich” (to A.J.). We thank Prof. Heinz Falk (Institute of Organic Chemistry, Johannes Kepler University Linz) for his generous hospitality to A.J. We are very grateful to Hannes Fuchs (LabTop Instruments) for his continuous and unselfish support.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Abbreviations

- Bodipy

(4,4-difluoro-5,7-dimethyl-4-bora-3′,4′-adiaza-S-indacene-3-propionyl)-N-iodoacetylethylenediamine

- Phg

Phenylglycine

- Cs*

Bodipy-labeled Cys

- Nle

Norleucine

- Xaa

Any amino acid

- PheLac

Phenyllactic acid

References

- Amiche M, Delfour A, Nicolas P. Opioid peptides from frog skin. EXS. 1998;85:57–71. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-8837-0_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai L, Sheeley S, Sweedler JV. Analysis of endogenous d-amino acid-containing peptides in metazoa. Bioanal Rev. 2009;1(1):7–24. doi: 10.1007/s12566-009-0001-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal PS, Torres AM, Crossett B, Wong KK, Koh JM, Geraghty DP, Vandenberg JI, Kuchel PW. Substrate specificity of platypus venom l-to-d-peptide isomerase. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(14):8969–8975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709762200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson DA, Karsch-Mizrachi I, Lipman DJ, Ostell J, Wheeler DL (2008) GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res 36 (Database issue):D25–D30. doi:10.1093/nar/gkm929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bozzi A, Mangoni ML, Rinaldi AC, Mignogna G, Aschi M. Folding propensity and biological activity of peptides: the effect of a single stereochemical isomerization on the conformational properties of bombinins in aqueous solution. Biopolymers. 2008;89(9):769–778. doi: 10.1002/bip.21006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buczek O, Bulaj G, Olivera BM. Conotoxins and the posttranslational modification of secreted gene products. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62(24):3067–3079. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5283-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buczek O, Yoshikami D, Bulaj G, Jimenez EC, Olivera BM. Post-translational amino acid isomerization: a functionally important d-amino acid in an excitatory peptide. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(6):4247–4253. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405835200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buczek O, Yoshikami D, Watkins M, Bulaj G, Jimenez EC, Olivera BM. Characterization of D-amino-acid-containing excitatory conotoxins and redefinition of the I-conotoxin superfamily. FEBS J. 2005;272(16):4178–4188. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro MS, Ferreira TC, Cilli EM, Crusca E, Jr, Mendes-Giannini MJ, Sebben A, Ricart CA, Sousa MV, Fontes W. Hylin a1, the first cytolytic peptide isolated from the arboreal South American frog Hypsiboas albopunctatus (“spotted tree frog”) Peptides. 2009;30(2):291–296. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Wang L, Zeller M, Hornshaw M, Wu Y, Zhou M, Li J, Hang X, Cai J, Chen T, Shaw C (2010) Kassorins: novel innate immune system peptides from skin secretions of the African hyperoliid frogs, Kassina maculata and Kassina senegalensis. Mol Immunol. doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2010.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Conlon JM, Kolodziejek J, Nowotny N, Leprince J, Vaudry H, Coquet L, Jouenne T, King JD. Characterization of antimicrobial peptides from the skin secretions of the Malaysian frogs, Odorrana hosii and Hylarana picturata (Anura:Ranidae) Toxicon. 2008;52(3):465–473. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2008.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conlon JM, Demandt A, Nielsen PF, Leprince J, Vaudry H, Woodhams DC. The alyteserins: two families of antimicrobial peptides from the skin secretions of the midwife toad Alytes obstetricans (Alytidae) Peptides. 2009;30(6):1069–1073. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gößler-Schöfberger R, Hesser G, Muik M, Wechselberger C, Jilek A. An orphan dermaseptin from frog skin reversibly assembles to amyloid-like aggregates in a pH-dependent fashion. FEBS J. 2009;276(20):5849–5859. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudmundsson GH, Agerberth B, Odeberg J, Bergman T, Olsson B, Salcedo R. The human gene FALL39 and processing of the cathelin precursor to the antibacterial peptide LL-37 in granulocytes. Eur J Biochem. 1996;238(2):325–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0325z.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldane JBS. Enzymes. London: Longmans, Green and Co.; 1930. [Google Scholar]

- Halverson T, Basir YJ, Knoop FC, Conlon JM. Purification and characterization of antimicrobial peptides from the skin of the North American green frog Rana clamitans. Peptides. 2000;21(4):469–476. doi: 10.1016/S0196-9781(00)00178-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada N, Iijima S, Kobayashi K, Yoshida T, Brown WR, Hibi T, Oshima A, Morikawa M. Human IgGFc binding protein (FcgammaBP) in colonic epithelial cells exhibits mucin-like structure. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(24):15232–15241. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.24.15232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck SD, Siok CJ, Krapcho KJ, Kelbaugh PR, Thadeio PF, Welch MJ, Williams RD, Ganong AH, Kelly ME, Lanzetti AJ, Gray WR, Phillips D, Parks TN, Jackson H, Ahlijanian MK, Saccomano NA, Volkmann RA. Functional consequences of posttranslational isomerization of Ser46 in a calcium channel toxin. Science. 1994;266(5187):1065–1068. doi: 10.1126/science.7973665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck SD, Faraci WS, Kelbaugh PR, Saccomano NA, Thadeio PF, Volkmann RA. Posttranslational amino acid epimerization: enzyme-catalyzed isomerization of amino acid residues in peptide chains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(9):4036–4039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellsten U, Harland RM, Gilchrist MJ, Hendrix D, Jurka J, Kapitonov V, Ovcharenko I, Putnam NH, Shu S, Taher L, Blitz IL, Blumberg B, Dichmann DS, Dubchak I, Amaya E, Detter JC, Fletcher R, Gerhard DS, Goodstein D, Graves T, Grigoriev IV, Grimwood J, Kawashima T, Lindquist E, Lucas SM, Mead PE, Mitros T, Ogino H, Ohta Y, Poliakov AV, Pollet N, Robert J, Salamov A, Sater AK, Schmutz J, Terry A, Vize PD, Warren WC, Wells D, Wills A, Wilson RK, Zimmerman LB, Zorn AM, Grainger R, Grammer T, Khokha MK, Richardson PM, Rokhsar DS. The genome of the Western clawed frog Xenopus tropicalis. Science. 2010;328(5978):633–636. doi: 10.1126/science.1183670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jilek A, Kreil G. d-amino acids in animal peptides. Chemical Monthly. 2008;139(1):1–5. doi: 10.1007/s00706-007-0780-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jilek A, Mollay C, Tippelt C, Grassi J, Mignogna G, Müllegger J, Sander V, Fehrer C, Barra D, Kreil G. Biosynthesis of a d-amino acid in peptide linkage by an enzyme from frog skin secretions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(12):4235–4239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500789102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamatani Y, Minakata H, Kenny PT, Iwashita T, Watanabe K, Funase K, Sun XP, Yongsiri A, Kim KH, Novales-Li P, et al. Achatin-I, an endogenous neuroexcitatory tetrapeptide from Achatina fulica Ferussac containing a d-amino acid residue. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;160(3):1015–1020. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(89)80103-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh JM, Chow SJ, Crossett B, Kuchel PW. Mammalian peptide isomerase: platypus-type activity is present in mouse heart. Chem Biodivers. 2010;7(6):1603–1611. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200900300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs JM, Mant CT, Kwok SC, Osguthorpe DJ, Hodges RS. Quantitation of the nearest-neighbour effects of amino acid side-chains that restrict conformational freedom of the polypeptide chain using reversed-phase liquid chromatography of synthetic model peptides with l- and d-amino acid substitutions. J Chromatogr A. 2006;1123(2):212–224. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2006.04.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreil G. d-amino acids in animal peptides. Annu Rev Biochem. 1997;66:337–345. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreil G, Barra D, Simmaco M, Erspamer V, Erspamer GF, Negri L, Severini C, Corsi R, Melchiorri P. Deltorphin, a novel amphibian skin peptide with high selectivity and affinity for delta opioid receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 1989;162(1):123–128. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90611-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai R, Zheng YT, Shen JH, Liu GJ, Liu H, Lee WH, Tang SZ, Zhang Y. Antimicrobial peptides from skin secretions of Chinese red belly toad Bombina maxima. Peptides. 2002;23(3):427–435. doi: 10.1016/S0196-9781(01)00641-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus LH, Bryant SD, Cooper PS, Salvadori S. What peptides these deltorphins be. Prog Neurobiol. 1999;57(4):377–420. doi: 10.1016/S0301-0082(98)00050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangoni ML, Grovale N, Giorgi A, Mignogna G, Simmaco M, Barra D. Structure-function relationships in bombinins H, antimicrobial peptides from Bombina skin secretions. Peptides. 2000;21(11):1673–1679. doi: 10.1016/S0196-9781(00)00316-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangoni ML, Papo N, Saugar JM, Barra D, Shai Y, Simmaco M, Rivas L. Effect of natural l- to d-amino acid conversion on the organization, membrane binding, and biological function of the antimicrobial peptides bombinins H. Biochemistry. 2006;45(13):4266–4276. doi: 10.1021/bi052150y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maselli VM, Brinkworth CS, Bowie JH, Tyler MJ. Host-defence skin peptides of the Australian Common Froglet Crinia signifera: sequence determination using positive and negative ion electrospray mass spectra. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2004;18(18):2155–2161. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mignogna G, Simmaco M, Kreil G, Barra D. Antibacterial and haemolytic peptides containing D-alloisoleucine from the skin of Bombina variegata. EMBO J. 1993;12(12):4829–4832. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06172.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montecucchi PC, de Castiglione R, Piani S, Gozzini L, Erspamer V. Amino acid composition and sequence of dermorphin, a novel opiate-like peptide from the skin of Phyllomedusa sauvagei. Int J Pept Protein Res. 1981;17(3):275–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1981.tb01993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mor A, Delfour A, Sagan S, Amiche M, Pradelles P, Rossier J, Nicolas P. Isolation of dermenkephalin from amphibian skin, a high-affinity delta-selective opioid heptapeptide containing a d-amino acid residue. FEBS Lett. 1989;255(2):269–274. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81104-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negri L, Melchiorri P, Lattanzi R. Pharmacology of amphibian opiate peptides. Peptides. 2000;21(11):1639–1647. doi: 10.1016/S0196-9781(00)00295-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta N, Kubota I, Takao T, Shimonishi Y, Yasuda-Kamatani Y, Minakata H, Nomoto K, Muneoka Y, Kobayashi M. Fulicin, a novel neuropeptide containing a d-amino acid residue isolated from the ganglia of Achatina fulica. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;178(2):486–493. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(91)90133-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ollivaux C, Gallois D, Amiche M, Boscameric M, Soyez D. Molecular and cellular specificity of post-translational aminoacyl isomerization in the crustacean hyperglycaemic hormone family. FEBS J. 2009;276(17):4790–4802. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry SJ, Yi-Kung Huang E, Cronk D, Bagust J, Sharma R, Walker RJ, Wilson S, Burke JF. A human gene encoding morphine modulating peptides related to NPFF and FMRFamide. FEBS Lett. 1997;409(3):426–430. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(97)00557-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonwetter BS, Stolzenberg ED, Zasloff MA. Epithelial antibiotics induced at sites of inflammation. Science. 1995;267(5204):1645–1648. doi: 10.1126/science.7886453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmaco M, Kreil G, Barra D. Bombinins, antimicrobial peptides from Bombina species. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1788(8):1551–1555. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GG, Reddy GV. Effect of the side chain on the racemization of amino acids in aqueous solution. J Org Chem. 2002;54(19):4529–4535. doi: 10.1021/jo00280a017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soyez D, Van Herp F, Rossier J, Le Caer JP, Tensen CP, Lafont R (1994) Evidence for a conformational polymorphism of invertebrate neurohormones. d-amino acid residue in crustacean hyperglycemic peptides. J Biol Chem 269 (28):18295–18298 [PubMed]

- Soyez D, Toullec JY, Ollivaux C, Geraud G. l to d amino acid isomerization in a peptide hormone is a late post-translational event occurring in specialized neurosecretory cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(48):37870–37875. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007302200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang YQ, Selsted ME. Characterization of the disulfide motif in BNBD-12, an antimicrobial beta-defensin peptide from bovine neutrophils. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(9):6649–6653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres AM, Tsampazi C, Geraghty DP, Bansal PS, Alewood PF, Kuchel PW. d-amino acid residue in a defensin-like peptide from platypus venom: effect on structure and chromatographic properties. Biochem J. 2005;391(Pt 2):215–220. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres AM, Tsampazi M, Tsampazi C, Kennett EC, Belov K, Geraghty DP, Bansal PS, Alewood PF, Kuchel PW. Mammalian l-to-d-amino-acid-residue isomerase from platypus venom. FEBS Lett. 2006;580(6):1587–1591. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.01.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres AM, Tsampazi M, Kennett EC, Belov K, Geraghty DP, Bansal PS, Alewood PF, Kuchel PW. Characterization and isolation of l-to-d-amino-acid-residue isomerase from platypus venom. Amino Acids. 2007;32(1):63–68. doi: 10.1007/s00726-006-0346-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechselberger C. Cloning of cDNAs encoding new peptides of the dermaseptin-family. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1388(1):279–283. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4838(98)00202-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechselberger C, Severini C, Kreil G, Negri L. A new opioid peptide predicted from cloned cDNAs from skin of Pachymedusa dacnicolor and Agalychnis annae. FEBS Lett. 1998;429(1):41–43. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(98)00545-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zangger K, Gößler R, Khatai L, Lohner K, Jilek A. Structures of the glycine-rich diastereomeric peptides bombinin H2 and H4. Toxicon. 2008;52(2):246–254. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.