Cardiometabolic risk (CMR) refers to risk factors that increase the likelihood of experiencing vascular events or developing diabetes. This concept encompasses traditional risk factors included in risk calculators, such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, and smoking, as well as emerging risk factors, such as abdominal obesity, inflammatory profile, and ethnicity.1 These factors are best identified by primary care providers, as most patients will present at an early stage with no symptoms. As 30% of deaths in Canada are due to cardiovascular disease (CVD), the identification and reduction of CMR will have an important effect on a disease that is an enormous public health concern. The cost to the Canadian economy from CVD alone is $22.2 billion per year in physician services, hospital costs, lost wages, and decreased productivity. The risk factors leading to CVD are widespread. For example, in Canada, 6.6% of people older than 20 years of age have diabetes; 19% of the adult population has hypertension; 18% of those aged 15 years and older are smokers; and 24.1% of those older than 30 years of age are obese.2 Family physicians are best suited to systematically screen patients, identify those at high risk, and intervene to prevent CVD.

The Cardiometabolic Risk Working Group (CMRWG) includes representatives from the relevant national professional societies and interest groups. The CMRWG recently synthesized a position paper1 to clarify the concept and management of CMR, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular risk assessment in the multiethnic Canadian context. The recommendations are consistent with Canadian guidelines, but in the areas not covered by existing guidelines, searches of high-quality primary studies and review articles were performed. This article summarizes a consolidated approach to the identification and management of CMR for a primary care audience.

Pathophysiology

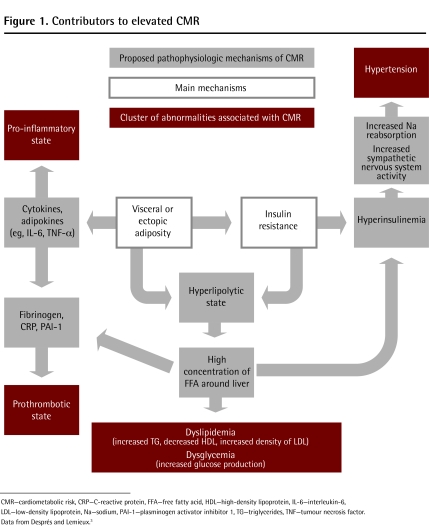

Abdominal fat—particularly visceral or ectopic adiposity—and insulin resistance are the main contributors to elevated CMR (Figure 1).3 Abdominal obesity results in an increase in circulating free fatty acids, an increase in cytokines that promote inflammation and hypertension, and a reduction of adipokines (eg, adiponectin), which normally regulate both glucose and lipid metabolism.4 These changes are important factors in the development of insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and an inflammatory and prothrombotic state—pivotal factors in the development of both atherosclerosis and type 2 diabetes.

Figure 1.

Contributors to elevated CMR

CMR—cardiometabolic risk, CRP—C-reactive protein, FFA—free fatty acid, HDL—high-density lipoprotein, IL-6—interleukin-6, LDL—low-density lipoprotein, Na—sodium, PAI-1—plasminogen activator inhibitor 1, TG—triglycerides, TNF—tumour necrosis factor. Data from Després and Lemieux.3

Cardiometabolic risk factors

Recognized traditional risk factors for CVD include age, sex, family history, hypertension, dysglycemia, dyslipidemia, and smoking. Newer cardiovascular risk factors include abdominal obesity (measured by waist circumference), insulin resistance, inflammation as measured by high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) levels, lack of consumption of fruits and vegetables, sedentary lifestyle, and psychosocial stress. While traditional parameters are routinely assessed in the clinic, waist circumference should be added to the routine evaluation of cardiovascular risk. In patients whose triglyceride levels are elevated, an apolipoprotein B measurement can replace that of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) for the purpose of risk assessment and management of CMR.

The INTERHEART study assessed in 27 000 subjects from 52 countries a range of traditional and emerging risk factors in individuals with myocardial infarction compared with a control population.5 It identified 9 risk factors that accounted for 90% of the population-attributable risk of myocardial infarction in men and 94% in women: abnormal lipids, smoking, hypertension, diabetes, abdominal obesity, psychosocial stress, lack of consumption of fruits and vegetables, lack of moderate alcohol consumption, and lack of physical activity. This study indicated the importance of both traditional and emerging risk factors (especially abdominal obesity, psychosocial stress, diet, and lack of physical activity) and the need to encourage the population, and especially patients at high risk, to make changes to reduce these risk factors.

Accordingly, regular screening for CMR allows clinicians to identify high-risk individuals who might not otherwise be defined as high risk when examined using traditional approaches only. Early assessment of a patient’s CMR profile facilitates individualized therapeutic strategies that might prevent long-term complications.

Cardiometabolic risk assessment

Cardiometabolic risk assessment is recommended for all individuals 40 years of age and older and for those aged 18 to 39 years with any of the following criteria:

a high-risk ethnic background (aboriginal, South Asian, and black),

a family history of premature CVD (younger than 55 years of age in male and younger than 65 years of age in female first-degree relatives), and

at least 1 traditional or emerging risk factor. (Note that hypertension and abdominal obesity are reasons for screening in all age groups, including those individuals younger than 18 years old.)

A comprehensive risk assessment should include a thorough documentation of the patient’s history (age, ethnicity, smoking status, physical activity level, diet, family history of premature CVD or type 2 diabetes, and comorbidities), physical examination (body mass index, waist circumference, and blood pressure), and laboratory test results (fasting plasma glucose, creatinine or estimated glomerular filtration rate, and fasting lipid profile). If elevated risk is suggested or suspected, further laboratory tests should be considered (eg, hemoglobin A1c, electrocardiogram, exercise stress test, apolipoprotein B, and hsCRP).

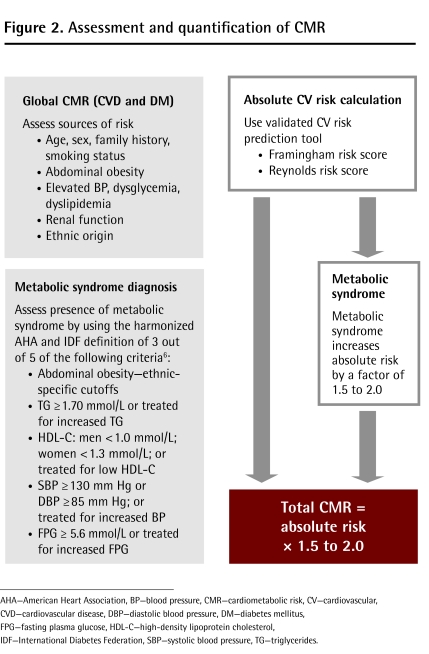

The final step is to quantify total risk using a validated algorithm such as the Framingham or Reynolds scores, and then add the effect of the metabolic syndrome. Risk scores calculate absolute risk, which is the likelihood of a vascular event within a given time period. The metabolic syndrome considers a specific subset of cardiovascular risk factors and implies a relative risk. The new harmonized International Diabetes Federation criteria for metabolic syndrome require the presence of at least 3 of 5 of the following: elevated waist circumference (corrected for ethnicity), increased blood pressure (≥ 130/85 mm Hg or receiving treatment), elevated fasting plasma glucose (≥ 5.6 mmol/L or receiving treatment), decreased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) (< 1.0 mmol/L for men and < 1.3 mmol/L for women), and increased triglycerides (≥ 1.7 mmol/L).6 The presence of the metabolic syndrome does not necessarily confer a high absolute risk of CVD, but rather a higher risk relative to a person without those criteria. If the metabolic syndrome is present, the calculated absolute risk should be multiplied by 1.5 to 2 (Figure 26).7 This provides a better representation of the true risk and allows for prompt behavioural intervention and pharmacotherapy, as needed.

Figure 2.

Assessment and quantification of CMR

AHA—American Heart Association, BP—blood pressure, CMR—cardiometabolic risk, CV—cardiovascular, CVD—cardiovascular disease, DBP—diastolic blood pressure, DM—diabetes mellitus, FPG—fasting plasma glucose, HDL-C—high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, IDF—International Diabetes Federation, SBP—systolic blood pressure, TG—triglycerides.

Integrated management of CMR

The primary treatment of elevated CMR is lifestyle modification. This includes simultaneous counseling on physical activity, caloric intake, diet composition, and smoking cessation (along with nicotine replacement, bupropion, or varenicline, as needed). The first course of therapy is regular exercise (3 to 5 d/wk; 30 to 60 min/d), coupled with improved diet quality and a reduction of 500 kcal per day. The most important nutritional consideration in reducing CMR is weight reduction through caloric restriction, regardless of diet composition. The goal is to achieve a sustainable weight loss of no more than 0.5 kg per week in those who are overweight.

Regular exercise of moderate intensity has been associated with positive reductions in waist circumference, weight, and visceral fat. Caloric restriction shows a consistent decline in waist circumference for obese individuals, and evidence suggests that each kilogram of weight lost because of caloric restriction alone is associated with an approximately 1-cm decrease in waist circumference.8 Insulin resistance is improved with both exercise and caloric restriction. Exercise modestly increases HDL-C levels with little effect on LDL-C levels, while caloric restriction reduces LDL-C with little effect on HDL-C.9 Blood pressure can effectively be lowered with exercise, while caloric restriction has a limited and modest effect.10 Nonetheless, health risk improves even with modest reductions in blood pressure.11

Lifestyle modifications should be pursued for 3 to 6 months in all patients before add-on pharmacotherapy is considered, unless patients are at high risk. The greatest health improvements occur among patients with the worst cardiometabolic disturbances, and sustained efforts are necessary to maintain cardiovascular benefits.12 Thus, the importance of continuing health behaviour change should be stressed to the patient even if pharmacotherapy has been initiated.

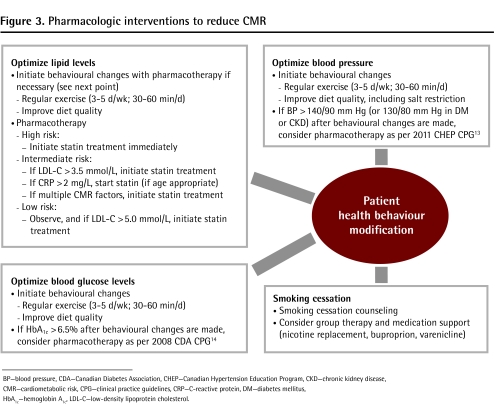

Figure 313,14 provides a comprehensive treatment algorithm for patients with increased CMR. First of all, start statin therapy in parallel with initiation of behavioural modifications in patients who are at high risk (more than 20% CVD risk over the next 10 years). Those at intermediate risk (10% to 19% CVD risk in the next 10 years) with LDL levels greater than 3.4 mmol/L or hsCRP levels greater than 2.0 mg/L (in men older than age 50 or women older than age 60) should also receive statins after a trial of lifestyle modification. The goal is to attain the target LDL-C level (< 2.0 mmol/L or a decrease of current LDL-C level by ≥ 50%) or an apolipoprotein B level less than 0.8 g/L.15 Second, in patients with prediabetes (impaired fasting glucose or impaired glucose tolerance), weight loss and increased physical activity is the preferred approach to preventing or delaying onset of diabetes, but pharmacotherapy can also be considered. Metformin is the preferred pharmacologic therapy for patients with prediabetes or diabetes after 3 to 6 months of behaviour modification have failed to achieve the desired outcomes. Progressively more aggressive antihyperglycemic therapy will be required to maintain optimal glycemic levels in patients with diabetes. Finally, antihypertensive therapy should be initiated after appropriate assessment as recommended by the 2011 Canadian Hypertension Education Program clinical practice guidelines.13

Figure 3.

Pharmacologic interventions to reduce CMR

BP—blood pressure, CDA—Canadian Diabetes Association, CHEP—Canadian Hypertension Education Program, CKD—chronic kidney disease, CMR—cardiometabolic risk, CPG—clinical practice guidelines, CRP—C-reactive protein, DM—diabetes mellitus, HbA1c—hemoglobin A1c, LDL-C—low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

In the case of severe obesity (class 3 or class 2 plus comorbid conditions) with insufficient weight loss despite behavioural or pharmacologic treatment, bariatric surgery might be considered when there is an acceptable operative risk. Bariatric surgery has been shown to lower all-cause mortality by 24% to 40%, improve quality of life, and reverse abnormal glucose metabolism including diabetes, but late complications might arise from nutritional deficiencies and behavioural changes.16

The Study of Health Assessment and Risk in Ethnic Groups highlights the point that findings from studies carried out in European populations cannot always be extrapolated to other ethnocultural populations.17 For instance, South Asian and Chinese populations demonstrate increased CMR at body mass index or waist circumference levels traditionally considered to be “normal”; accordingly, ethnic-specific thresholds should be applied to these subpopulations. White Canadians have a lower incidence of hypertension and lower LDL-C levels than Canadian South Asians and lower rates of obesity and smoking relative to Canadian aboriginals. Furthermore, black Canadians have a higher prevalence of hypertension and present at an earlier age. Taken together, the evidence to date supports the importance of integrating a patient’s ethnicity and culture into the assessment and management of CMR.

Conclusion

Elevated CMR is a key driver of cardiovascular events. Owing to the high prevalence of CMR factors, prompt assessment and appropriate treatment in primary care are needed to help reduce future complications. Most of these patients have no known conditions and are best identified during routine screening. Addressing CMR is not about labeling patients, but rather targeting health promotion efforts to prevent disease. The CMRWG position statement1 provides a practical stepwise algorithm for management. Risk assessment involves identifying both traditional and emerging risk factors, and then using this information to quantify an absolute risk of cardiovascular events. The key treatments involve counseling on behaviour change by family physicians and primary care teams, and referral to exercise specialists (kinesiologists) and registered dieticians where possible.18 Vascular protective measures such as pharmacotherapy and bariatric surgery for weight reduction might be needed for patients at high risk. This approach systematizes prevention of diabetes and vascular disease in primary care by effectively addressing the underlying causes of these conditions.

Footnotes

This article is eligible for Mainpro-M1 credits. To earn credits, go to www.cfp.ca and click on the Mainpro link.

La traduction en français de cet article se trouve à www.cfp.ca dans la table des matières du numéro d’avril 2012 à la page e196.

Competing interests

Dr Leiter has received research funding from, has provided continuing medical education on behalf of, or has acted as a consultant to Abbott, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, and Servier. Dr Fitchett has received research funding from, has provided continuing medical education on behalf of, or has acted as a consultant to AstraZeneca, Biovail, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, and Schering Plough. Dr Harris has received research funding from, has provided continuing medical education on behalf of, or has acted as a consultant to AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Roche, and Sanofi.

References

- 1.Leiter LA, Fitchett DH, Gilbert RE, Gupta M, Mancini GB, McFarlane PA, et al. Cardiometabolic risk in Canada: a detailed analysis and position paper by the cardiometabolic risk working group. Can J Cardiol. 2011;27(2):e1–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2010.12.054. Available from: www.cfpc.ca/uploadedFiles/Resources/Resource_Items/Health_Professionals/Cardiometabolic_risk_working_group.pdf. Accessed 2012 Feb 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heart and Stroke Foundation [website] Statistics. Ottawa, ON: 2012. Available from: www.heartandstroke.com/site/c.ikIQLcMWJtE/b.3483991/k.34A8/Statistics.htm. Accessed 2011 Aug 9. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Després JP, Lemieux I. Abdominal obesity and metabolic syndrome. Nature. 2006;444(7121):881–7. doi: 10.1038/nature05488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cornier MA, Dabelea D, Hernandez TL, Lindstrom RC, Steig AJ, Stob NR, et al. The metabolic syndrome. Endocr Rev. 2008;29(7):777–822. doi: 10.1210/er.2008-0024. Epub 2008 Oct 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364(9438):937–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120(16):1640–5. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644. Epub 2009 Oct 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galassi A, Reynolds K, He J. Metabolic syndrome and risk of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2006;119(10):812–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ross R, Dagnone D, Jones PJ, Smith H, Paddags A, Hudson R, et al. Reduction in obesity and related comorbid conditions after diet-induced weight loss or exercise-induced weight loss in men. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(2):92–103. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-2-200007180-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dattilo AM, Kris-Etherton PM. Effects of weight reduction on blood lipids and lipoproteins: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;56(2):320–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/56.2.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arroll B, Beaglehole R. Does physical activity lower blood pressure: a critical review of the clinical trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(5):439–47. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cook NR, Cohen J, Hebert PR, Taylor JO, Hennekens CH. Implications of small reductions in diastolic blood pressure for primary prevention. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155(7):701–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leiter LA, Fitchett DH, Gilbert RE, Gupta M, Mancini GB, McFarlane PA, et al. Identification and management of cardiometabolic risk in Canada: a position paper by the Cardiometabolic Risk Working Group (executive summary) Can J Cardiol. 2011;27(2):124–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2011.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hypertension Canada [website] Recommendations. Markham, ON: Canadian Hypertension Education Program; 2011. Available from: www.hypertension.ca/chep-recommendations. Accessed 2012 Feb 8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Canadian Diabetes Association Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee Canadian Diabetes Association 2008 clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of diabetes in Canada. Can J Diabetes. 2008;32(Suppl 1):S1–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Genest J, McPherson R, Frohlich J, Anderson T, Campbell N, Carpentier A, et al. 2009 Canadian Cardiovascular Society/Canadian guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of dyslipidemia and prevention of cardiovascular disease in the adult—2009 recommendations. Can J Cardiol. 2009;25(10):567–79. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(09)70715-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sjöström L, Lindroos AK, Peltonen M, Torgerson J, Bouchard C, Carlsson B, et al. Lifestyle, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(26):2683–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anand SS, Yusuf S, Vuksan V, Devanesen S, Teo KK, Montague PA, et al. Differences in risk factors, atherosclerosis, and cardiovascular disease between ethnic groups in Canada: the Study of Health Assessment and Risk in Ethnic groups (SHARE) Lancet. 2000;356(9226):279–84. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02502-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lau DC, Douketis JD, Morrison KM, Hramiak IM, Sharma AM, Ur E. 2006 Canadian clinical practice guidelines on the management and prevention of obesity in adults and children [summary] CMAJ. 2007;176(8):1–13. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.061409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]