Abstract

Background

The co-occurrence of substance use disorder (SUD) and major depressive disorder (MDD) is common and is often thought to impair response to antidepressant therapy. These patients are often excluded from clinical trials, resulting in a significant knowledge gap regarding optimal pharmacotherapy for the treatment of MDD with concurrent SUD.

Methods

In the Combining Medications to Enhance Depression Outcomes study, 665 adult outpatients with chronic and/or recurrent MDD were prospectively treated with either escitalopram monotherapy (escitalopram and placebo) or an antidepressant combination (venalfaxine-XR and mirtazapine or escitalopram and bupropion-SR). Participants with MDD and concurrent SUD (13.1%) were compared to those without SUD (86.9%) on sociodemographic and clinical characteristics at baseline and treatment response at 12-week and 28-week endpoints.

Results

The participants with MDD and SUD were more likely to be male and have current suicidal thoughts/plans, and had a greater lifetime severity and number of suicide attempts, and a higher number of concurrent Axis I disorders, particularly concurrent anxiety disorders. There were no significant differences between the MDD with or without SUD groups in terms of dose, time in treatment, response or remission at week 12 and 28. Furthermore, no significant differences in response or remission rates were noted between groups on the basis of the presence or absence of SUD and treatment assignment.

Conclusions

Although significant baseline sociodemographic and clinical differences exist, patients with MDD and concurrent SUD are as likely to respond and remit to a single or combination antidepressant treatment as those presenting without SUD.

Keywords: major depressive disorder, substance use disorder, dual diagnosis, combination antidepressants, treatment outcome

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 25–30% of individuals with major depressive disorder (MDD) endorse symptoms of concurrent substance use disorders (SUD)1 and these disorders are associated with a substantially higher mortality rate.2 Compared to depressed patients without SUD, those with SUD are significantly more likely to be younger, male, never married, unemployed, without insurance, and to have lower incomes and fewer years of schooling3,4,5,6 and are significantly more likely to have onset of MDD before age 18, a positive family history of SUD, a history of suicide attempts, a higher current risk of suicide, recurrent depression, atypical symptoms of depression, and more concurrent Axis I disorders. These differences are most notable in individuals with MDD who endorse both alcohol and drug use disorders.6

In practice, clinicians are often reticent to begin antidepressant treatment of MDD with concurrent SUD, with the expectation that antidepressants will be ineffective or that the depression will resolve spontaneously in most individuals if abstinence is achieved.7,8,9,10 As noted in a review by Ostacher,11 few definitive studies exist to actually guide clinicians in managing patients presenting with MDD and co-occurring SUD. Our current knowledge is the result of studies from two distinct populations – those seeking treatment for MDD who have SUD and those seeking treatment for SUD noted to have depression. The studies of those seeking treatment for SUD with co-occurring MDD dominate the literature. A meta-analysis12 of fourteen double-blind, randomized controlled studies for the treatment of depression in patients with SUD, indicated that the pooled effect size of antidepressant treatment outcome was modest (i.e., 0.38).

Our recent report examined the effect of SUD on treatment outcomes in patients with MDD participants in the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study. This study recruited a sample (N=2838) considerably larger than any previous study mentioned above (Ns=28 to 113).12 Despite numerous baseline clinical differences, the STAR*D study found no significant differences in response rates to citalopram between MDD participants with and without SUD.6 Although there was nonsignificant difference in remission rates between those with MDD (33%) compared to MDD+alcohol (36%) or MDD+drug (28%), those MDD participants with both alcohol and drug use had significantly lower rates of remission (22.5%) and longer time to achieve remission. In other words, those individuals with MDD who endorsed both alcohol and drug use were 42% less likely to achieve remission than those without SUD. When we examined the citalopram treatment outcomes for the MDD participants with both a concurrent anxiety disorder and SUD,13 a somewhat different pattern emerged. Those participants with MDD+anxiety disorder+SUD had poorer outcomes (25% remission and 43% response rates) than those with MDD-only (40% remission and 52% response rates), suggesting that although response rates are fairly consistent, achieving remission is a more challenging treatment issue in persons with increased illness burden.

The Combining Medications to Enhance Depression Outcomes (CO-MED) study14 provides a unique opportunity to examine whether treatment outcomes to either an antidepressant medication monotherapy or antidepressant medication combination therapies among patients with chronic and/or recurrent MDD differ by the presence or absence of comorbid SUD. Although this study did not prospectively stratify randomization based on SUD status, the large sample allows for exploratory outcome analysis between groups and thus, extends the STAR*D findings. In addition to comparing depression treatment outcomes, we also examined the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of MDD patients with and without comorbid SUD in order to replicate the findings from the STAR*D study and learn more about how to better identify and clinically manage these dual diagnosed patients.

METHODS

Study Overview

This study was conducted using a large sample obtained from the CO-MED trial. CO-MED was a 7-month, multisite, single-blind, randomized trial that compared the efficacy of escitalopram (ESCIT) + placebo (PBO) vs. each of two different antidepressant medication (ADM) combinations (bupropion-sustained release+escitalopram and venlafaxine-extended release+mirtazapine) (1:1:1 ratio) as a first-step MDD treatment, including acute (12 weeks) and long-term continuation treatment (total 28 weeks). Study details and methodology are available elsewhere (www.co-med.org).14 A planned sample size of 660 subjects would detect a 15% difference in remission rate between each ADM combination and ESCIT+PBO (with an expected remission rate of 35%). This difference was viewed as sufficiently large to impact practice because the number needed to treat would be seven (NNT=7), which approximates the benefit of a single ADM over placebo in successful antidepressant registration trials for MDD.15

Participants

This study was conducted according to the principals of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol and consent form were approved and overseen by the National Institute of Mental Health Data and Safety Monitoring Board and by Institutional Review Boards at the National Coordinating Center (The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas), the University of Pittsburgh Data Coordinating Center, each participating Regional Center and all relevant clinical sites. Prior to study entry, the study procedures, alternatives, potential risks and benefits were explained to participants, who provided written informed consent. Participants were recruited from six primary care and nine psychiatric care sites across the United States.

Broad inclusion and minimal exclusion criteria (www.co-med.org) ensured a reasonably representative participant sample. Briefly, eligibility criteria included: outpatient; 18–75 years of age; met DSM-IV TR criteria16 for either recurrent (≥1 prior major depressive episode [MDE]) or chronic (current MDE for ≥2 years) MDD based on a clinical interview and confirmed using a DSM-IV MDD symptom checklist completed by the clinical research coordinator (CRC); in the index episode for ≥2 months; scored ≥16 on the 17-Item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD17);17 and did not have any psychotic illness or bipolar disorder.

Baseline Data

Sociodemographic and clinical features were gathered at baseline and included assessment of anxious features (>7 on the anxiety/somatization subscale of the baseline HSRD17),18 current Axis I disorders (self-report Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire [PDSQ]),19,20, 21 the presence, severity, and functional impact of common general medical comorbidities ([GMCs] a self-administered Comorbidity Questionnaire),22 sleep disturbances, lethargy, melancholic and atypical features (specific item scores on the 30-item Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology – Clinician-rated [IDS-C30])23,24,25 suicidal ideation (the Concise Health Risk Tracking – Self-Report scale),26 and associated symptoms (Concise Associated Symptom Tracking – Self-Rated scale). The Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale27 was conducted as a safety measure to evaluate the uncommon, but adverse, occurrence of antidepressant-induced manic symptoms in persons with unrecognized bipolar disorder.28

Identification of SUD

The presence of SUD was defined as the presence of any drug and/or alcohol use disorder (excluding nicotine or caffeine) in the past 6 months based on the participant’s response on the baseline PDSQ. The PDSQ is a self-report 126-item “yes” or “no” screening instrument that evaluates the presence or absence of thirteen DSM-IV disorders.29,30 The PDSQ is a sensitive screening tool that has been validated against the “gold standard” diagnostic interview, the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. The cut-off score used in this study has been shown in an SUD population to yield sensitivities of 92.4% and 91.9% and specificities of 71.4% and 82.4% for alcohol use disorder and drug use disorders, respectively.31 A threshold of one or more endorsed items per diagnostic category was selected to indicate positive symptoms of a drug use disorder and/or alcohol use disorder.32 The presence of concurrent Axis I psychiatric disorders, including SUD, was established using PDSQ responses set at a threshold that established 90% specificity.33 With this specificity, we can infer that 9 of 10 participants identified as endorsing SUD would have met criteria for SUD by DSM-IV. Based on this cut-off, the sensitivity and specificity corresponds to 85/80 for alcohol use disorders and 85/87 for drug use disorders. In addition, the positive and negative predictive values are 27% and 98% for alcohol use disorders and 18% and 99% for drug use disorders, respectively. Based on this threshold, if a participant was positive on the PDSQ for either drug or alcohol use disorder, they were considered to be positive for SUD in our analyses (i.e. SUD+).

Antidepressant Treatment

A 12-week study period was chosen for the primary analysis so that (a) maximal doses could be delivered for at least four weeks, (b) most participants whose depression could remit would do so without an excessively long trial,34 and (c) attrition might be minimized. Treatment and assessment visits occurred at baseline and weeks 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 16, 20, 24 and 28. Dosage adjustments were guided by the CO-MED Operations Manual (available at www.co-med.org), which utilized measurement-based care to provide personally-tailored and vigorous dosing,35,36 with dosage adjustments based on the 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology – Clinician-rated (QIDS-C16),37 the Frequency, Intensity and Burden of Side Effects Rating (FIBSER)38 and the measurement of participant adherence obtained at each treatment visit.

Treatment was randomly assigned, stratified by clinical site using a Web-based randomization system.39 Random block sizes of three and six were used to minimize the probability of identifying the next treatment assignment. Dosing schedules were based on prior reports.40,41,42 Doses were increased only in the context of acceptable tolerability and participants could exit the study if intolerable side effects occurred despite dose reduction or treatment of side effects. Medication dosage and blinding guidelines are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Medication dosage guidelines and blinded conditions.

| Week of Treatment | Open Label | Single Blind |

|---|---|---|

| Escitalopram + Placebo | ||

| Escitalopram | Placeboa | |

| Baseline | 10 mg/d | |

| Week 2 | 1 tablet/d | |

| Week 4 | 20 mg/db | 2 tablets/d |

| Bupropion-SR + Escitalopram | ||

| Bupropion-SR | Escitaloprama | |

| Baseline | 150 mg/d | |

| Week 1 | 300 mg/d | |

| Week 2 | 10 mg/d | |

| Week 4 | 400 mg/db | 20 mg/db |

| Week 6+ | 400 mg/db | 20 mg/db |

| Venlafaxine-XR + Mirtazapine | ||

| Venlafaxine-XR | Mirtazapinea | |

| Baseline | 37.5 mg/d | |

| Day 4 | 75 mg/d | |

| Week 1 | 150 mg/d | |

| Week 2 | 15 mg/d | |

| Week 4 | 225 mg/d | 30 mg/d |

| Week 6 | 45 mg/db | |

| Week 8 | 300 mg/db | |

Note: all medication increases were on the conditions that QIDS-C16 >5 and side effects were tolerable.

Participant blinded to this medication throughout the 7-month study. Research coordinators and physicians were not blinded to any medication to maximize safety and facilitate informed flexible dosing decisions.

Maximum dose (bupropion SR was in divided dose).

Research Outcomes

The primary outcome, symptom remission, was based on the 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology – Self-Report (QIDS-SR16). Remission was ascribed a priori based on the last two consecutive measurements obtained during the 12-week acute trial to ensure that a single “good week” was not falsely signaling remission. At least one of these ratings had to be <6, while the other had to be <8. If participants exited before 12 weeks, their last two consecutive QIDS-SR16 scores were used to ascribe remission. Those who exited before having two post-baseline measures were considered not remitted. Response was defined as a ≥50% decrease in QIDS-SR16 score from baseline.

Participants could exit the study if they had received a maximally tolerated dose(s) for ≥4 weeks by week 8 without receiving a ≥30% reduction from baseline QIDS-C16. They could enter continuation treatment (weeks 12–28) if they had received an acceptable benefit (defined as a QIDS-C16 ≤9 by week 12) or if they reached a QIDS-C16 of 10–13 with clinician and participant judging the benefit to be substantial enough to indicate a treatment continuation. Thus, virtually all participants entering the continuation phase had at least a 40% reduction in baseline QIDS-C16.

Secondary outcomes included attrition, anxiety (the anxiety subscale of the IDS-C30), function (Work and Social Adjustment Scale),43 quality of life (Quality of Life Inventory),44,45 specific side effects (Systematic Assessment for Treatment-Emergent Events–Systematic Inquiry [SAFTEE-SI]),46,47 cognitive and physical functioning (Cognitive and Physical Functioning Questionnaire),48 and side-effect burden (FIBSER).

Statistical Analyses

Participants were grouped by the presence/absence of SUD (SUD+ and SUD- groups, respectively). These two groups were compared regarding sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, and antidepressant treatment outcomes. Descriptive statistics, including measures of central tendency and dispersion, were computed for continuous data. Frequency distributions were estimated for categorical data. The appropriate parametric (e.g., t-test) or nonparametric test (e.g., chi-square, Wilcoxon tests) was used to assure a balanced distribution of the sociodemographic, psychiatric and medical characteristics among participants with and without SUD. At 12 and 28 weeks, unadjusted and adjusted outcomes were compared among those with and without SUD using regression models. The type of regression model varied by outcome and included linear regression, logistic regression, ordinal logistic regression and negative binomial regression models. Potential confounders were identified using a stepwise logistic regression model with an indicator of SUD as the outcome and all other baseline characteristics as independent variables. Those variables that remained in the final stepwise model were considered as potential confounders in the adjusted models. The moderating effect of SUD on treatment was evaluated on two outcomes, severity of depression (QIDS-SR16) and side effect burden (FIBSER), at 12 and 28 weeks. For severity of depression, a linear regression model was fit, and for side effect burden an ordinal logistic regression model was fit. Both models included main effects for treatment and SUD, as well as the two-way interaction between treatment and SUD. All analyses are considered to be exploratory in nature and a type I error or a p-value <0.05 was used as a threshold to identify statistical significance. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons because this is a secondary, post-hoc exploratory, analysis and results should be interpreted accordingly.

The percent change in QIDS-SR16 was calculated using the difference between the baseline and last QIDS-SR16 scores, divided by the baseline QIDS-SR16 score. Logistic regression models were developed to estimate the association of psychotropic medication use with remission and response, after controlling for differences between regional centers and the effect of baseline characteristics that were not balanced among those with and without SUD. Time to first remission/response was defined as the first observed point of remission/response based on the QIDS-SR16. With respect to the adjustment for regional center (i.e. site), it is common practice in multi-center trials to control for site as a way of controlling for unmeasured site differences. The cumulative proportions of each group that failed to remit/respond by various time points was plotted using Kaplan-Meier curves, and log rank tests were used to compare the cumulative proportions of the two groups.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

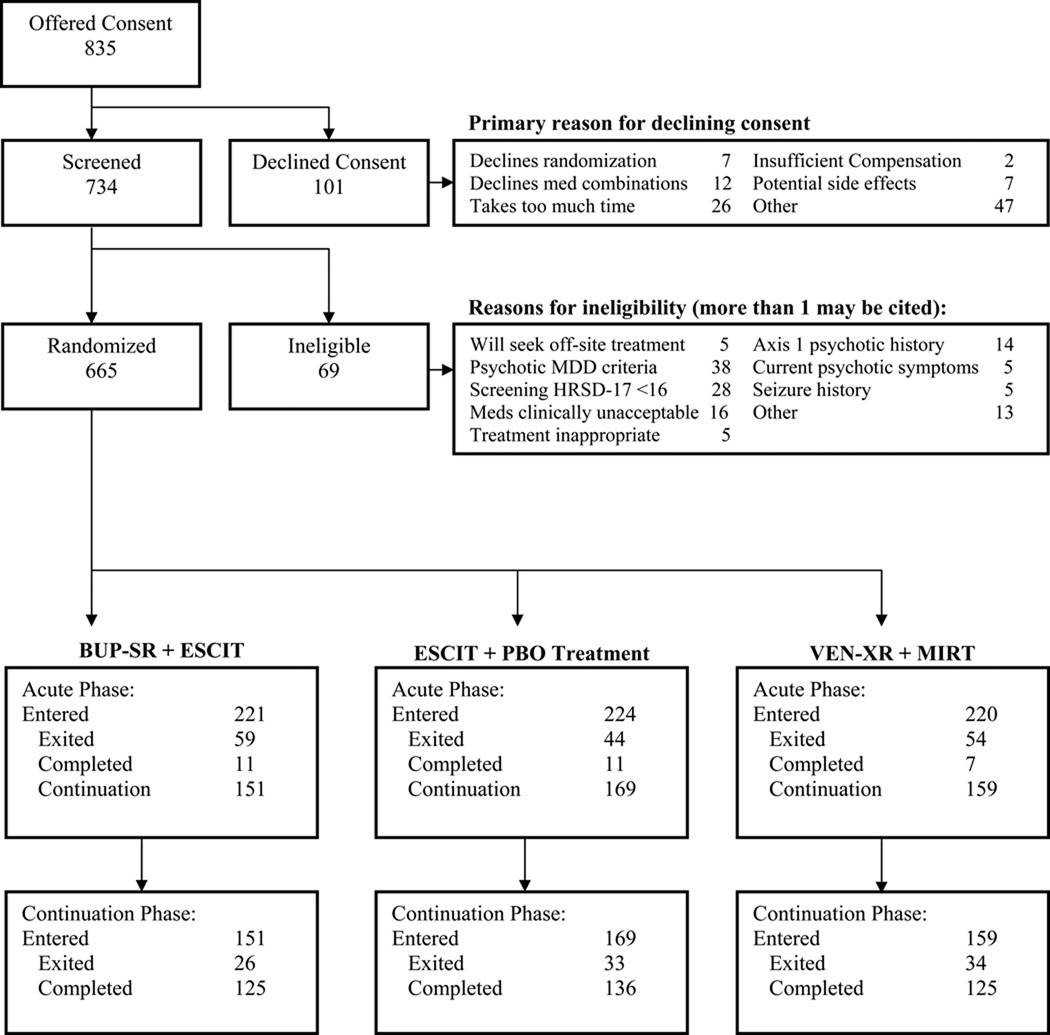

From March 2008 through February 2009, the study randomized n=665 subjects (Figure 1). One subject did not complete the baseline PDSQ, leaving 664 evaluable participants, of whom 13.1% (n=87) screened positive for concurrent SUD (2.3% had both drug and alcohol use disorders, 3% had drug use disorder only, and 7.8% had alcohol use disorder only). Compared to SUD- participants, SUD+ participants were significantly more likely to be male and more likely to have current suicidal thoughts/plans, a history of suicide attempts, more prior suicide attempts, a greater lifetime severity of suicidality, higher self reported mania score, increased irritability, anxiety and mania scores, less sleep disturbance, and older age for sexual abuse (Table 2). SUD+ participants also screened positive on the PDSQ for a higher number of concurrent Axis I psychiatric disorders —particularly concurrent anxiety disorders (Table 3).

Figure 1.

CONSORT Flow Diagram

Abbreviations: BUP-SR = bupropion-sustained release, ESCIT = escitalopram, PBO = placebo, VEN-XR = venlafaxine-extended release, MIRT = mirtazapine,

TABLE 2.

Baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of subjects with MDD with and without concurrent substance use disorder

| Baseline Characteristic | Substance Use Disorder |

Analyses |

Baseline Characteristic |

Substance Use Disorder |

Analyses |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present N=87 (13.1%) |

Absent N=577 (86.9%) |

Test Statistic | p- value |

Present N=87 (13.1%) |

Absent N=577 (86.9%) |

Test Statistic |

p- value |

||

| n (%) | n (%) | ||||||||

| Age | χ2(2)=5.2149 | 0.0737 | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||||

| 18–29 | 22 (25.3) | 114 (9.8) | Age | 41.1 (12.0) | 43.0 (13.1) | t(662)=|1.26| | 0.2085 | ||

| 30–54 | 54 (62.1) | 330 (57.2) | Education | 13.4 (2.8) | 13.8 (3.0) | t(638)=|1.07| | 0.2862 | ||

| 55–75 | 11 (12.6) | 133 (23.1) | Monthly household income | 1882 (1856) | 2791 (5671) | χ2(1)=1.4798 | 0.2238 | ||

| Sex | χ2(1)=19.871 | <.0001 | Age at first episode | 24.0 (14.1) | 24.0 (14.1) | χ2(1)=0.008 | 0.9286 | ||

| Male | 46 (59.2) | 167 (28.9) | Years since first episode | 17.1 (13.0) | 18.9 (13.7) | χ2(1)=1.6282 | 0.2019 | ||

| Female | 41 (47.1) | 410 (71.1) | N prior episodes | 10.7 (22.8) | 8.7 (19.4) | χ2(1)=0.642 | 0.4230 | ||

| Race | χ2(2)=2.1663 | 0.3385 | N suicide attempts | 0.32 (0.91) | 0.23 (1.38) | χ2(1)=6.3731 | 0.0116 | ||

| White | 52 (63.4) | 378 (67.5) | Age neglected | 7.0 (4.5) | 7.2 (4.2) | t(236)=|0.33| | 0.7385 | ||

| Black | 27 (32.9) | 147 (26.3) | Age emotionally abused | 8.1 (4.0) | 7.8 (4.2) | t(255)=|0.43| | 0.6697 | ||

| Other | 3 (3.7) | 35 (6.3) | Age physically abused | 5.9 (3.5) | 7.8 (3.9) | t(126)=|1.93| | 0.0557 | ||

| Hispanic | 10 (11.5) | 91 (15.8) | χ2(1)=1.0723 | 0.3004 | Age sexually abused | 11.2 (3.5) | 8.7 (4.0) | t(143)=|2.27| | 0.0249 |

| Employed | 43 (49.4) | 287 (49.7) | χ2(1)=0.003 | 0.9563 | N prior antidepressants | 1.3 (1.5) | 1.6 (1.8) | χ2(1)=2.6307 | 0.1048 |

| Clinical setting | χ2(1)=0.9958 | 0.3183 | N concomitant medications | 2.7 (2.2) | 3.0 (2.9) | χ2(1)=0.0676 | 0.7949 | ||

| Primary | 41 (47.1) | 305 (52.9) | Current episode duration (mo) | 55.7 (96.2) | 62.7 (106) | χ2(1)=0.0045 | 0.9464 | ||

| Psychiatric | 46 (52.9) | 272 (47.1) | HRSD17 | 23.5 (5.3) | 23.9 (4.7) | t(660)=|0.69| | 0.4888 | ||

| Chronic MDD (2+ yrs) | 50 (57.5) | 318 (55.3) | χ2(1)=0.1437 | 0.7046 | IDS-C30 | 38.0 (9.6) | 38.0 (9.0) | t(662)=|0.0| | 0.9982 |

| Chronic/recurrent MDD | χ2(2)=0.2134 | 0.8988 | QIDS-C16 | 15.7 (3.5) | 15.8 (3.4) | t(662)=|0.35| | 0.7233 | ||

| Chronic only | 19 (21.8) | 127 (22.1) | QIDS-SR16 | 15.8 (4.1) | 15.4 (4.3) | t(643)=|0.8| | 0.4254 | ||

| Recurrent only | 37 (2.5) | 257 (44.7) | ASRMS | 2.1 (2.4) | 1.4 (2.2) | χ2(1)=8.6101 | 0.0033 | ||

| Both | 31 (35.6) | 191 (33.2) | CAST-SR | ||||||

| QIDS-SR16 | χ2(3)=2.8574 | 0.4141 | Irritability | 13.3 (3.4) | 12.2 (3.8) | t(661)=|2.47| | 0.0136 | ||

| 0–10 none/mild | 8 (9.3) | 73 (13.1) | Anxiety | 6.8 (2.9) | 6.1 (2.9) | χ2(1)=4.1182 | 0.0424 | ||

| 11–15 moderate | 35 (40.7) | 203 (36.3) | Mania | 4.3 (3.0) | 3.5 (2.7) | χ2(1)=4.429 | 0.0353 | ||

| 16–20 severe | 31 (36.0) | 228 (40.8) | Insomnia | 5.4 (2.2) | 5.0 (2.3) | t(661)=|1.34| | 0.1810 | ||

| 21–27 very severe | 12 (14.0) | 55 (9.8) | Panic | 2.9 (2.1) | 2.6 (2.2) | χ2(1)=2.2519 | 0.1334 | ||

| Anxious features | 60 (69.0) | 436 (75.6) | χ2(1)=1.7413 | 0.1870 | CHRT-SR | ||||

| Atypical features | 15 (7.2) | 87 (15.1) | χ2(1)=0.2721 | 0.6019 | Loneliness | 3.4 (1.9) | 3.4 (2.0) | t(661)=|0.28| | 0.7827 |

| Melancholic features | 14 (17.5) | 110 (21.0) | χ2(1)=0.5188 | 0.4713 | Despair | 4.7 (2.2) | 4.3 (2.2) | t(662)=|1.51| | 0.1326 |

| Lethargic (IDS-C30) | 54 (62.1) | 397 (68.8) | χ2(1)=1.574 | 0.2096 | Ideation | 2.8 (3.1) | 2.0 (2.6) | χ2(1)=6.5761 | 0.0103 |

| Sleep disturbance (IDS-C30) | 70 (80.5) | 517 (89.6) | χ2(1)=6.1628 | 0.0130 | Total | 10.9 (5.4) | 9.7 (5.3) | t(661)=|2.07| | 0.0386 |

| Age of first episode <18 | 38 (43.7) | 257 (44.7) | χ2(1)=0.0317 | 0.8588 | CPFQ | 27.3 (6.6) | 27.7 (5.7) | t(662)=|0.46| | 0.6455 |

| At least 1 prior episode | 68 (78.2) | 448 (77.9) | χ2(1)=0.0027 | 0.9586 | QOLI | −1.4 (1.9) | −1.2 (1.9) | t(658)=|1.17| | 0.2413 |

| CHRT-SR suicidal thoughts/plans | 21 (24.1) | 89 (15.4) | χ2(1)=4.1527 | 0.0416 | WSAS | 27.0 (8.4) | 26.9 (8.9) | χ2(1)=0.0129 | 0.9096 |

| Ever attempted suicide | 14 (16.7) | 45 (8.1) | χ2(1)=6.4735 | 0.0109 | |||||

| Lifetime severity of suicidality | (P)<0.0001 | 0.0334 | |||||||

| None | 23 (27.4) | 175 (31.4) | |||||||

| Thoughts of dying | 16 (19.0) | 161 (28.9) | |||||||

| Suicidal thoughts | 11 (13.1) | 86 (15.4) | |||||||

| Specific method | 11 (13.1) | 48 (8.6) | |||||||

| Plan/gesture | 5 (6.0) | 33 (5.9) | |||||||

| Preparation | 4 (4.8) | 10 (1.8) | |||||||

| Attempt | 14 (16.7) | 45 (8.1) | |||||||

| Abuse/neglect before age 18 | |||||||||

| Neglected | 35 (40.2) | 204 (35.4) | χ2(1)=0.7596 | 0.3835 | |||||

| Emotionally abused | 39 (44.8) | 221 (38.4) | χ2(1)=1.3231 | 0.2500 | |||||

| Physically abused | 17 (19.5) | 113 (19.6) | χ2(1)=0.0003 | 0.9864 | |||||

| Sexually abused | 15 (17.2) | 130 (22.6) | χ2(1)=1.2726 | 0.2593 | |||||

| Abused | 45 (51.7) | 264 (45.9) | χ2(1)=1.0252 | 0.3113 | |||||

NOTE: Chi-square for continuous measures indicates Kruskal-Wallis test.

Number in parentheses after t-test indicated number of sample included in the test.

Number in parentheses after χ2 reflects n-1 of groups tested

Denominator is number of women.

Abbreviations: MDD = major depressive disorder, HRSD17 = 17-item Hamilton rating scale for depression, IDS-C30 = 30-item inventory of depressive symptomatology – clinician-rated, QIDS-SR16 = 16-item quick inventory of depressive symptomatology - self-rated, QIDS-C16 = 16-item quick inventory of depressive symptomatology - clinician-rated, ASRMS = Altman self-rating mania scale, CAST-SR = concise associated symptom tracking - self-rated, CHRT-SR = concise health risk tracking - self-rated, CPFQ = cognitive and physical functioning questionnaire, QOLI = quality of life inventory, WSAS = work and social adjustment scale.

Table 3.

Baseline co-morbidity characteristics of subjects with MDD with and without concurrent substance use disorder

| Baseline Characteristic | Substance Use Disorder |

Analyses |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present N=87 (13.1%) |

Absent N=577 (86.9%) |

Test Statistic |

p- value |

|

| n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Axis I Disorder (PDSQ) | ||||

| Agoraphobia | 18 (20.7) | 51 (8.8) | χ2(1)=11.402 | 0.0007 |

| Bulimia | 11 (12.6) | 67 (11.6) | χ2(1)=0.0776 | 0.7805 |

| Generalized anxiety | 25 (28.7) | 106 (18.4) | χ2(1)=5.1284 | 0.0235 |

| Hypochondriasis | 9 (10.3) | 20 (3.5) | (P)=0.006 | 0.0081 |

| Obsessive-compulsive | 15 (17.2) | 64 (11.1) | χ2(1)=2.7275 | 0.0986 |

| Panic | 12 (13.8) | 52 (9.0) | χ2(1)=1.9841 | 0.1590 |

| Post-traumatic stress | 17 (19.5) | 63 (10.9) | χ2(1)=5.3033 | 0.0213 |

| Social phobia | 35 (40.2) | 143 (24.8) | χ2(1)=9.1932 | 0.0024 |

| Somatoform | 1 (1.1) | 20 (3.5) | (P)=0.1636 | 0.3410 |

| Number of Axis 1 Disorders (PDSQ) | χ2(4)=107.66 | <.0001 | ||

| 0 | 296 (51.3) | |||

| 1 | 27 (31.0) | 132 (22.9) | ||

| 2 | 23 (26.4) | 69 (12.0) | ||

| 3 | 9 (10.3) | 41 (7.1) | ||

| 4+ | 28 (32.2) | 39 (6.8) | ||

| Medical Conditions (SCQ) | ||||

| Back pain | 11 (12.8) | 101 (17.5) | χ2(1)=1.1845 | 0.2764 |

| Diabetes | 3 (3.4) | 71 (12.3) | χ2(1)=5.9886 | 0.0144 |

| Heart | 4 (4.6) | 36 (6.2) | χ2(1)=0.3598 | 0.5486 |

| Neuropsychological | 2 (2.3) | 16 (2.8) | (P)=0.2807 | 1.0000 |

| Number Medical Conditions (SCQ) | χ2(3)=4.665 | 0.1980 | ||

| 0 | 45 (52.3) | 282 (49.0) | ||

| 1 | 25 (29.1) | 133 (23.1) | ||

| 2 | 11 (12.8) | 87 (15.1) | ||

| 3+ | 5 (5.8) | 74 (12.8) | ||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| SCQ | 3.0 (3.4) | 3.4 (3.5) | χ2(1)=1.0867 | 0.2972 |

| N treated SCQ health problems | 0.80 (1.20) | 1.00 (1.28) | χ2(1)=1.5701 | 0.2102 |

NOTE: Chi-square for continuous measures indicates Kruskal-Wallis test.

Abbreviations: PDSQ = psychiatric diagnostic screening questionnaire, SCQ = self-administered comorbidity questionnaire.

Outcome Measures by Presence or Absence of SUD

Treatment outcomes were similar at 12 weeks (Table 4) and 28 weeks (Table 5) between the SUD- and SUD+ groups in terms of remission rates, response rates, and dose (maximum dose, last dose). There was no difference between groups for time in treatment or medication intolerance. The SUD+ group had fewer post-baseline visits attended (4.8 ±2.2 vs. 5.4 ±2.2, p= 0.0055 at week 12; 6.9 ±3.8 vs. 7.8 ±3.7, p= 0.0187 at week 28). The only significant difference regarding serious adverse events (SAEs) was a greater percentage of SUD+ participants having at least one psychiatric SAE during the 28-week period compared to SUD- participants, although the absolute number was low for both groups. There were no SAEs related to suicidal ideation requiring hospitalization.

Table 4.

Week 12 outcome measures in subjects with chronic and/or recurrent MDD with and without concurrent substance use disorder

| Measure | Substance Use Disorder |

Analyses |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present N=87 (13.1%) |

Absent N=577 (86.9%) |

Unadjusted | Adjusteda | |||

| n (%) | n (%) |

OR (95%CI) |

p-value |

OR (95%CI) |

p-value | |

| Remission (last 2 consecutive QIDS-SR16 <6 and <8) | 25 (28.7) | 230 (39.9) | 0.69 (0.41,1.18) |

0.1756 | 0.70 (0.4,1.19) |

0.1782 |

| Last QIDS-SR16 <6 | 24 (27.6) | 215 (37.6) | 0.65 (0.38,1.11) |

0.1130 | 0.61 (0.35,1.07) |

0.0834 |

| Response (≥50% reduction QIDS-SR 16) | 41 (47.7) | 292 (52.5) | 0.95 (0.58,1.55) |

0.8235 | 1.004 (0.6,1.67) |

0.9874 |

| Exited acute phase | 31 (35.6) | 154 (26.7) | 1.7 (1.01,2.85) |

0.0456 | 1.64 (0.96,2.81) |

0.0689 |

| Last WSAS | 1.31 (0.84,2.01) |

0.2365 | 1.35 (0.85,2.13) |

0.2056 | ||

| 0 | 15 (18.1) | 91 (16.7) | ||||

| 1–10 | 14 (16.9) | 157 (28.9) | ||||

| 11–20 | 21 (25.3) | 121 (22.2) | ||||

| 21–30 | 15 (18.1) | 105 (19.3) | ||||

| –40 | 18 (21.7) | 70 (12.9) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | β | β | |||

| Maximum SAFTEE N worsenings | 10.2 (7.4) | 9.4 (6.1) | 0.996 | 0.9551 | 0.998 | 0.9757 |

| Last SAFTEE N worsenings | 5.9 (5.8) | 50 (4.9) | 0.143 | 0.2401 | 0.2033 | |

| Last QIDS-SR16 | 9.3 (5.5) | 8.0 (5.4) | 0.914 | 0.1788 | 0.890 | 0.1961 |

| Percent QIDS-SR16 change | −41 (32.5) | −47 (34.5) | 3.721 | 0.3894 | 2.388 | 0.5885 |

| IDS-C30 anxiety subscale | 2.9 (2.0) | 2.6 (2.1) | 0.092 | 0.3944 | 0.098 | 0.3683 |

| Last QOLI | −0.20 (2.59) | 0.23 (2.28) | −0.222 | 0.4631 | −0.178 | 0.5670 |

Adjusted for treatment, gender, PDSQ Hypochondriasis, insomnia.

Abbreviations: QIDS-SR16 = 16-item quick inventory of depressive symptomatology - self-rated, WSAS = work and social adjustment scale, SAFTEE = systematic assessment for treatment-emergent events, QOLI = quality of life inventory, PDSQ = psychiatric diagnostic screening questionnaire.

Table 5.

Week 28 outcome measures in subjects with chronic and/or recurrent MDD with and without concurrent substance use disorder

| Measure | Substance Use Disorder |

Analyses |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present N=87 (13.1%) |

Absent N=577 (86.9%) |

Unadjusted | Adjusteda | |||

| n (%) | n (%) |

OR (95%CI) |

p-value |

OR (95%CI) |

p-value | |

| Remission (last 2 consecutive QIDS-SR16 <6 and <8) | 30 (34.5) | 267 (46.3) | 0.61 (0.38,0.98) |

0.0406 | 0.62 (0.38,1.01) |

0.0534 |

| Last QIDS-SR16 <6 | 31 (35.6) | 260 (45.6) | 0.66 (0.41,1.06) |

0.0823 | 0.66 (0.41,1.07) |

0.09 |

| Response(≥50% QIDS-SR16) | 46 (53.5) | 327 (59.1) | 0.79 (0.5,1.25) |

0.3240 | 0.84 (0.52,1.35) |

0.4717 |

| Exited continuation phase | 39 (44.8) | 213 (36.9) | 1.39 (0.88,2.19) |

0.1575 | 1.33 (0.83,2.13) |

0.2378 |

| At least 1 SAE | 8 (9.2) | 38 (6.6) | 1.44 (0.65,3.19) |

0.3739 | 1.59 (0.69,3.64) |

0.2704 |

| At least 1 psychiatric SAE | 5 (5.7) | 10 (1.7) | 3.46 (1.15,10.37) |

0.0268 | 4.86 (1.54,15.33) |

0.0071 |

| Last WSAS | 1.86 (1.23,2.81) |

0.0031 | 1.87 (1.22,2.86) |

0.0037 | ||

| 0 | 17 (20.5) | 121 (22.2) | ||||

| 1–10 | 14 (16.9) | 156 (28.6) | ||||

| 11–20 | 14 (16.9) | 120 (22.0) | ||||

| 21–30 | 17 (20.5) | 80 (14.7) | ||||

| 31–40 | 21 (25.3) | 68 (12.5) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | β | β | |||

| Maximum SAFTEE N worsenings | 10.9 (8.3) | 10.0 (6.4) | 0.995 | 0.9487 | 0.987 | 0.8708 |

| Last SAFTEE N worsenings | 5.6 (6.1) | 4.8 (5.2) | 0.108 | 0.4278 | 0.070 | 0.6209 |

| Last QIDS-SR16 | 8.7 (5.6) | 7.4 (5.5) | 1.223 | 0.0376 | 1.222 | 0.0414 |

| Percent QIDS-SR16 change | −44 (32.8) | −51 (35.4) | 5.132 | 0.2466 | 3.653 | 0.4191 |

| IDS-C30 anxiety subscale | 2.5 (2.2) | 2.5 (2.1) | −0.034 | 0.7770 | −0.063 | 0.6014 |

| Last QOLI | −0.12 (2.62) | 0.55 (2.34) | −0.507 | 0.1017 | −0.458 | 0.1505 |

Adjusted for treatment, gender, PDSQ Hypochondriasis, insomnia.

Abbreviations: QIDS-SR16 = 16-item quick inventory of depressive symptomatology - self-rated, SAE = serious adverse event, WSAS = work and social adjustment scale, SAFTEE = systematic assessment for treatment-emergent events, QOLI = quality of life inventory, PDSQ = psychiatric diagnostic screening questionnaire.

Outcome by Presence or Absence of SUD and Antidepressant Medication

As shown in Table 6, the effect of treatment was not different between those with and without SUD at week 12 or week 28 based on treatment group. However, at week 28 there was a differential effect on early termination with a significantly high early termination rate in the VEN+MIRT arm in those with SUD+ (10.1 ±9.6 vs.16.2 ±0.3; p=0.0138). Notably, there were no significant differences between groups regarding burden of side effects (FIBSER).

Table 6.

Selected outcome measures by substance use disorder and antidepressant treatment

| Measure | Substance Use Disorder |

Analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present |

Absent |

||||||

| BUP-SR + ESCIT n=34 |

ESCIT + PBO n=30 |

VEN-XR + MIRT n=23 |

BUP-SR + ESCIT n=186 |

ESCIT + PBO n=194 |

VEN-XR + MIRT n=197 |

||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | p-valuea | |

| Week 12 | |||||||

| Early termination | 15 (44.1) | 6 (20.0) | 10 (43.5) | 55 (29.6) | 49 (25.3) | 47 (23.9) | 0.1653 |

| Last QIDS-SR16 <6 | 11 (32.4) | 9 (30.0) | 4 (17.4) | 70 (38.0) | 72 (37.1) | 75 (38.5) | 0.4486 |

| Response (≥50% reduction QIDS-SR16) | 18 (52.9) | 13 (44.8) | 10 (43.5) | 92 (51.1) | 100 (52.9) | 100 (53.5) | 0.6597 |

| Last FIBSER burden | 0.3027 | ||||||

| No impairment | 18 (56.3) | 14 (46.7) | 12 (57.1) | 100 (56.8) | 103 (56.9) | 97 (51.3) | |

| Minimal/mild | 12 (37.5) | 9 (30.0) | 6 (28.6) | 56 (31.8) | 65 (35.9) | 66 (35.1) | |

| Moderate/marked | 1 (3.1) | 6 (20.0) | 2 (9.5) | 13 (7.4) | 10 (5.5) | 21 (11.2) | |

| Severe/intolerable | 1 (3.1) | 1 (3.3) | 1 (4.8) | 7 (4.0) | 3 (1.7) | 4 (2.1) | |

| Week 28 | |||||||

| Early termination | 16 (47.1) | 8 (26.7) | 15 (65.2) | 68 (36.6) | 70 (36.1) | 67 (34.0) | 0.0251 |

| Last QIDS-SR16 <6 | 11 (32.4) | 15 (50.0) | 5 (21.7) | 89 (48.6) | 86 (44.6) | 85 (43.8) | 0.1088 |

| Response (≥50% reduction QIDS-SR16) | 17 (50.0) | 19 (65.5) | 10 (43.5) | 107 (59.8) | 110 (58.5) | 110 (59.1) | 0.2720 |

| Last FIBSER burden | 0.1514 | ||||||

| No impairment | 21 (65.6) | 17 (56.7) | 14 (66.7) | 107 (60.5) | 118 (64.8) | 97 (51.6) | |

| Minimal/mild | 9 (28.1) | 6 (20.0) | 3 (14.3) | 50 (28.2) | 54 (29.7) | 61 (32.4) | |

| Moderate/marked | 1 (3.1) | 6 (20.0) | 3 (14.3) | 14 (7.9) | 7 (3.8) | 28 (14.9) | |

| Severe/intolerable | 1 (3.1) | 1 (3.3) | 1 (4.8) | 6 (3.4) | 3 (1.6) | 2 (1.1) | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Week 12 | |||||||

| Last QIDS-SR16 | 9.0 (5.3) | 9.1 (6.0) | 10.0 (5.3) | 8.0 (5.3) | 7.8 (5.1) | 8.2 (5.8) | 0.9063 |

| Percent QIDS-SR16 change | −41 (32.3) | −46 (31.9) | −35 (33.8) | −45 (35.1) | −47 (33.3) | −47 (35.2) | 0.5115 |

| Week 28 | |||||||

| Last QIDS-SR16 | 8.7 (5.5) | 7.6 (5.7) | 10.1 (5.4) | 7.1 (5.3) | 7.3 (5.3) | 7.9 (5.9) | 0.3239 |

| Percent QIDS-SR16 change | −42 (33.7) | −54 (31.3) | −35 (31.3) | −51 (36.8) | −51 (33.1) | −49 (36.4) | 0.2088 |

p-value associated with the substance use disorder by treatment interaction term.

Abbreviations: BUP-SR = bupropion-sustained release, ESCIT = escitalopram, PBO = placebo, VEN-XR = venlafaxine-extended release, MIRT = mirtazapine, QIDS-SR16 = 16-item quick inventory of depressive symptomatology – self-rated, FIBSER = frequency, intensity and burden of side effects rating.

DISCUSSION

The most important finding of this study is that despite greater lifetime suicidality and a greater number of concurrent Axis I psychiatric disorders at baseline, the presence of comorbid SUD in patients with chronic and/or recurrent MDD did not appear to significantly affect treatment outcomes with either a single SSRI or combination antidepressant medications in short- or long-term treatment periods. Our results extend and compliment the findings from the larger STAR*D study of first level citalopram monotheray in persons with MDD.

Curiously only 13% of the COMED participants had a concurrent SUD, which is much lower than the 30% prevalence rate found in the STAR*D MDD sample (which also used the PDSQ screening tool to assess for the presence of SUD).3,4 Possible reasons for this difference likely reflect differences in study design and subject selection. Although a formal analysis between these study samples was not conducted, the lower prevalence of concurrent SUD in the COMED study may be related to a greater representation of women in the COMED study (1:2.1 male:female) compared to STAR*D (1:1.7 male:female). Female participants in both studies were less likely to have SUD than their male counterparts; thus, effectively decreasing the population of SUD+ participants in the COMED study. Additionally, the COMED study enrolled subjects with chronic and/or recurrent depression, many of whom may have been counseled earlier in the course of their illness to decrease or abstain from substances. Entering a study involving taking two medications may have generated an unintended recruitment bias such that subjects with SUD were less likely to consent and researchers were more cautious to recruit these subjects.

Baseline characteristics of the COMED participants were similar to those of the STAR*D study in terms of ethnicity, employment, and levels of depressive symptom severity; however, a greater percentage of COMED participants endorsed chronic depression, reflecting the differences in inclusion criteria. Sociodemographically, this study supports previous observations that participants with MDD+SUD are more likely to be male49,50,51,52 and have a greater number of concurrent Axis I psychiatric disorders.6

While depressive symptom severity and side effect burden were comparable with antidepressant monotherapy and combination antidepressant therapy, the number of participants having one or more psychiatric SAEs was higher in the SUD+ group at 28 weeks, although absolute numbers were low. While the difference in number of post-baseline visits reached statistical difference, the numerical difference of less than one visit between groups is not likely to be clinically meaningful. Although the presence of comorbid SUD was not broadly associated with significant degrees of intolerability to three different antidepressant treatments, the SUD+ SUD+ participants on antidepressant combination therapy had greater rates of exit due to treatment intolerance (early termination) at 28 weeks than did SUD+ participants on monotherapy. Similarly, higher rates of early exit were observed in a study comparing combination treatment (sertraline + naltrexone) versus those on monotherapy.53 While this could reflect pharmacodynamic or pharmacokinetic differences in medication metabolism that result from substance abuse, in this study, maximum doses for all study drugs were similar between the SUD- and SUD+ groups, though there was a slight trend toward lower doses in the SUD+ group. Also of clinical importance is the finding that the SUD+ group appears to be at a higher risk of planning or making suicide attempts. The constellation of MDD, SUD and suicidality is complex with contributions from genetic, familial and sociocultural elements.54,55,56,57,58,59 These findings remind us that reinforcement of adherence to treatment, concern for medication tolerability, and need for close medical follow-up in the dual diagnosed patient are a clinically important. Clinicians need to be cognizant of the inherent risk of suicide in patients with MDD and SUD, and must offer adequate and timely treatment to reduce the risk of suicide. Fortunately, our findings demonstrate that no particular antidepressant or combination was consistently more effective regarding response, remission or side effect profile at 12 or 28 weeks and that the presence of comorbid SUD does not lessen the efficacy or tolerability of antidepressant mono- or combination medication treatments.

The strengths of the present study include 1) a large sample size with substantial minority and ethnic representation, 2) recruitment from both primary care and psychiatric care treatment settings, 3) enrollment of MDD participants from naturalistic treatment-seeking “real-world” patient populations, including those with SUD, 4) a single-blind, randomized design, and 5) a longer-term extended treatment phase.

Limitations of the present study include the use of a self-report screening tool to define concurrent SUD and other Axis I disorders while MDD was diagnoses more rigorously. We also did not gather information regarding the amounts or types of alcohol or drugs used, the types of treatment received for SUD, and the change in substance use following treatment of the depression. A more detailed diagnostic assessment and more detailed accounting of concurrent treatments and outcomes for the comorbid disorders was not obtained in view of the primary focus of the COMED study and need to limit participant burden. As such, we cannot address whether treatment of depression affected the concurrent SUD. The lack of a minimum period of abstinence prior to study entry did not systematically ensure that depressive symptoms would not spontaneously remit after sufficient abstinence. Also, we identified and examined comorbid SUD as a baseline correlate of treatment outcome to three different therapies. Ideally, prospectively randomizing groups of MDD patients with and without comorbid SUD to each of the three treatment groups would provide more definitive data on efficacy and tolerability. Lastly, since the participants were recruited from a psychiatric or primary care clinic, the results may not be generalizable to an addictions treatment clinic.

In conclusion, our findings of equivalent response and remission rates with single agent or combination antidepressant medication treatment in individuals who have chronic and/or recurrent MDD with or without SUD supports an emerging and important paradigm shift in clinical care. Namely, antidepressant medications may be equally beneficial for MDD patients who are struggling with alcohol and/or drug addictions and for MDD patients who are not. A study that prospectively addresses the clinical question of delaying or initiating antidepressant medication treatment in depressed patients while awaiting abstinence is warranted. The striking burden of suicidality imposed by the comorbidity of SUD is clear in this and other studies, and should heighten the urgency to assertively treat depression in patients who are also using drugs and/or alcohol. These findings may be useful for guiding the treatment of persons with chronic and/or recurrent MDD and concurrent SUD in primary care and psychiatric care clinics.

Acknowledgements

This project has been funded with Federal funds from the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health, under Contract N01MH90003 to the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas (P.I.: A.J. Rush). The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. The NIMH had no role in the drafting or review of the manuscript, nor in the collection or analysis of the data. We acknowledge the administrative support of the Research and Development Services at the participating VA Medical Centers. We would like to acknowledge the editorial support of Jon Kilner, MS, MA (Pittsburgh, PA).

Footnotes

Trial Registry Name: ClinicalTrials.gov

Registration identification number: NCT00590863

URL for the registry: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00590863?term=COMED&rank=1

References

- 1.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) JAMA. 2003;289:3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang CK, Hayes RD, Broadbent M, et al. All-cause mortality among people with serious mental illness (SMI), substance use disorders, and depressive disorders in southeast London: a cohort study. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:77. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis LL, Rush JA, Wisniewski SR, et al. Substance use disorder comorbidity in major depressive disorder: an exploratory analysis of the Sequence Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression cohort. Compr Psychiatry. 2005;46:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2004.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis LL, Frazier E, Husain MM, et al. Substance use disorder comorbidity in major depressive disorder: a confirmatory analysis of the STAR*D cohort. Am J Addict. 2006;15:278–285. doi: 10.1080/10550490600754317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis LL, Frazier E, Gaynes BN, et al. Are depressed outpatients with and without a family history of substance use disorder different? A baseline analysis of the STAR*D cohort. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1931–1938. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis LL, Wisniewski SR, Howland RH, et al. Does comorbid substance use disorder impair recovery from major depression with SSRI Treatment? An analysis of the STAR*D level one treatment outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;107:161–170. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hatsukami D, Pickens RW. Posttreatment depression in an alcohol and drug abuse population. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139:1563–1566. doi: 10.1176/ajp.139.12.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schuckit MA. Alcohol and depression: A clinical perspective. Acta Psychiatrica Scandanavia. 1994;377:28–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb05798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schuckit MA. Drug and Alcohol Abuse: A clinical guide to diagnosis and treatment. 5th ed. City Springer: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sedlacek DA, Miller SI. A framework for relating alcoholism and depression. J Fam Pract. 1982;14:41–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ostacher MJ. Comorbid alcohol and substance abuse dependence in depression: impact on the outcome of antidepressant treatment. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2007;30:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nunes EV, Levin FR. Treatment of depression in patients with alcohol or other drug dependence: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;291:1887–1896. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.15.1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howland RH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al. Concurrent anxiety and substance use disorders among outpatients with major depression: clinical features and effect on treatment outcome. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;99:248–260. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Stewart JW, et al. Combining medications to enhance depression outcomes (CO-MED): Acute and long-term outcomes: A single-blind randomized study. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:689–701. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Depression Guideline Panel, 1993. Clinical Practice Guideline, Number 5: Depression in Primary Care: Volume 2. Rockville, MD, USA: Treatment of Major Depression, Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2000. text revision. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–61. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fava M, Rush AJ, Alpert JE, et al. Difference in treatment outcome in outpatients with anxious versus nonanxious depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;65:342–351. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. A self-report scale to help make psychiatric diagnoses: the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001a;58:787–794. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.8.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. The Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire: development, reliability and validity. Compr Psychiatry. 2001b;42:175–189. doi: 10.1053/comp.2001.23126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rush AJ, Zimmerman M, Wisniewski SR, et al. Comorbid psychiatric disorders in depressed outpatients: Demographic and clinical features. J Affect Disord. 2005;87:43–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sangha O, Stucki G, Liang MH, et al. The Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire: a new method to assess comorbidity for clinical and health services research. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:156–163. doi: 10.1002/art.10993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rush AJ, Gullion CM, Basco MR, et al. The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS): psychometric properties. Psychol Med. 1996;26:477–486. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700035558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rush AJ, Carmody TJ, Reimitz PE. The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS): clinician (IDS-C) and self-report (IDS-SR) ratings of depressive symptoms. International Journal of Methods of Psychiatric Research. 2000;9:45–59. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, et al. The 16-Item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:573–583. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01866-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Morris DW, et al. Concise Health Risk Tracking (CHRT) Scale: A brief self-report and clinician-rating of suicidal risk. J Clin Psych. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11m06837. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Altman EG, Hedeker D, Peterson JL, et al. The Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;42:948–955. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(96)00548-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Correa R, Akiskal H, Gilmer W, Nierenberg AA, et al. Is unrecognized bipolar disorder a frequent contributor to apparent treatment resistant depression?? J Affect Disord. 2010;127:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. A self-report scale to help make psychiatric diagnoses: the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001a;58:787–794. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.8.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. The Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire: development, reliability and validity. Compr Psychiatry. 2001b;42:175–189. doi: 10.1053/comp.2001.23126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Magruder KM, Sonne SC, Brady KT, et al. Screening for co-occurring mental disorders in drug treatment populations. J. Drug Issues. 2005;35:593–605. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zimmerman M, Sheeran T, Chelminski I, Young D. Screening for psychiatric disorders in outpatients with DSM-IV substance use disorders. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2004;26:181–188. doi: 10.1016/S0740-5472(03)00207-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rush AJ, Zimmerman M, Wisniewski SR, et al. Comorbid psychiatric disorders in depressed outpatients: Demographic and clinical features. J Affect Disord. 2005;87:43–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al. STAR*D Study Team Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:28–40. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trivedi MH, Daly EJ. Measurement-based care for refractory depression: a clinical decision support model for clinical research and practice. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88:S61–S71. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Gaynes BN, et al. Maximizing the adequacy of medication treatment in controlled trials and clinical practice: STAR*D measurement-based care. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:2479–2489. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rush AJ, Bernstein IH, Trivedi MH, et al. An evaluation of the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression: a Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression trial report. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:493–501. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wisniewski SR, Rush AJ, Balasubramani GK, et al. Self-rated global measure of the frequency, intensity, and burden of side effects. J Psychiatr Pract. 2006;12:71–79. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200603000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wisniewski SR, Eng H, Meloro L, et al. Web-based communications and management of a multi-center clinical trial: the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) project. Clin Trials. 2004;1:87–398. doi: 10.1191/1740774504cn035oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fava M. Augmentation and combination strategies in treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:S4–S11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leuchter AF, Lesser IM, Trivedi MH, et al. An open pilot study of the combination of escitalopram and bupropion-SR for outpatients with major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Pract. 2008;14:271–280. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000336754.19566.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McGrath PJ, Stewart JW, Fava M, et al. Tranylcypromine versus venlafaxine plus mirtazapine following three failed antidepressant medication trials for depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1531–1541. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.9.1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mundt JC, Marks IM, Shear MK, et al. The Work and Social Adjustment Scale: a simple measure of impairment in functioning. Br J Psychiatry. 180:461–464. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.5.461. 202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Frisch MB. Manual and treatment guide for the Quality of Life Inventory. Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems, Inc.; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frisch MB, Clark MP, Rouse SV, et al. Predictive and treatment validity of life satisfaction and the quality of life inventory. Assessment. 2005;12:66–78. doi: 10.1177/1073191104268006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levine J, Schooler NR. SAFTEE. a technique for the systematic assessment of side effects in clinical trials. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1986;22:343–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Levine J, Schooler NR. General versus specific inquiry with SAFTEE. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1992;12:448. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199212000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fava M, Iosifescu DV, Pedrelli P, et al. Reliability and validity of the Massachusetts general hospital cognitive and physical functioning questionnaire. Psychother Psychosom. 2009;78:91–97. doi: 10.1159/000201934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fava M, Abraham M, Alpert J, et al. Gender differences in Axis I comorbidity among depressed outpatients. J Affect Disord. 1996;38:129–133. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(96)00004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McDermut W, Mattia J, Zimmerman M. Comorbidity burden and its impact on psychosocial morbidity in depressed outpatients. J Affect Disord. 2001;65:289–295. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00220-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Melartin TK, Rytsala HJ, Leskela US, et al. Current comorbidity of psychiatric disorders among DSM-IV major depressive disorder patients in psychiatric care in the Vantaa Depression Study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:126–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Salloum IM, Mezzich JE, Cornelius J, et al. Clinical profile of comorbid major depression and alcohol use disorders in an initial psychiatric evaluation. Compr Psychiatry. 1995;36:260–266. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(95)90070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pettinati HM, Oslin DV, Kampman KM, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial combining sertraline and naltrexone for treating co-occurring depression and alcohol dependence. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:668–675. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08060852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bossarte RM, Swahn MH. The associations between early alcohol use and suicide attempts among adolescents with a history of major depression. Addict Behav. 2011;36:532–535. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sher L, Stanley BH, Harkavy-Friedman JM, et al. Depressed patients with co-occurring alcohol use disorder: a unique patient population. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:907–915. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kuo PH, Neale MC, Walch D, et al. Genome wide linkage scans for major depression in individuals with alcohol dependence. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44:616–619. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nurnberger JI, Fofoud T, Flury L, et al. Evidence for a locus on chromosome 1 that influences vulnerability to alcoholism and affective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:718–724. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.5.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Statham DJ, Heath AC, Madden PA, et al. Suicidal behavior: an epidemiological and genetic study. Psychol Med. 1998;28:839–855. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798006916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lin N, Eisen SA, Scherrer JF, et al. The influence of familial and non-familial factors on the association between major depression and substance abuse/dependence in 1874 monozygotic male twin pairs. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1996;43:49–55. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(96)01287-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]