Abstract

Introduction

The study reports 10-year anatomical and visual outcome in patients who underwent pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) for complications due to proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR).

Methods

Retrospective analysis of patients undergoing 20G PPV from January 1999 to May 2010 for tractional retinal detachment (TRD) and non-clearing vitreous hemorrhage (NCVH) secondary to PDR recorded prospectively on an electronic patient record. The primary aim was to study anatomical success and eyes with visual acuity (VA) of ≤0.3 logMAR at last follow-up.

Results

There were 346 eyes of 249 patients with mean age of 55.63 years and follow-up of 1.44 years. In all, 95.3% of eyes had a flat retina at final follow-up. Overall 136/346 (39.4%) eyes had final VA of logMAR ≤0.3 (Snellen 6/12) and 129 (37.3%) had logMAR ≥1.0 (Snellen 6/60). In all, 50/181 (27.6%) eyes with TRD and 84/165 (50.9%) with NCVH achieved final VA of ≤0.3 logMAR (Snellen 6/12). A total of 218 (63.1%) showed ≥0.3 logMAR improvement from baseline to last follow-up. Both preoperative VA and final postoperative (post-op) VA (P<0.001) improved significantly with each year from 1999 to 2010. The commonest peroperative complication was iatrogenic retinal tear formation (28.4%). This was a risk factor for the development of post-op retinal detachment, odds ratio: 3.90 (95% confidence interval: 1.91–7.97, P=0.0002). Silicone oil was used in 5.2% of patients at the primary procedure. In all, 9.2% required removal of non clearing post vitrectomy hemorrhage.

Conclusions

Outcomes from vitreoretinal surgery for complications of diabetic retinopathy have improved. In addition, the visual outcome after diabetic vitrectomy steadily improved over the 10-year period, which may in part be due to the move to operate on patients with better vision.

Keywords: diabetes, proliferative diabetic retinopathy, tractional retinal detachment, non-clearing vitreous hemorrhage, vision

Introduction

There is a global increase in the prevalence of diabetes with an estimated 366 million people affected worldwide by 2030,1 of which 4.6 million will live in England.2 End-stage diabetic eye disease is the most important cause of severe visual impairment in the working age group, both globally3 and in the United Kingdom.4 Both the prevalence and severity5, 6 of diabetic retinopathy are increasing worldwide, and in poor and lower socioeconomic countries in particular.7 Tractional retinal detachment (TRD) and non-clearing vitreous hemorrhage (NCVH) are the two complications of proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR),8 which are treated with vitreoretinal surgical repair. Improvements in surgical techniques such as the use of wide-angled viewing systems, use of endolaser9, 10 and use of vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGF) inhibitors like bevacizumab11 and ranibizumab should have improved visual outcome since the first reported randomized controlled diabetic vitrectomy study12 but this requires further investigation.

The purpose of this study was to report the 10-year anatomical and visual outcome in patients who underwent pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) for complications of PDR under the supervision of a single surgeon (THW) at a teaching hospital in South East London, UK. This was to examine success rates, use of tamponade agents, reoperation rates, and complications. In addition variation in management and visual outcome was assessed over the 10-year period.

Patients and methods

A retrospective analysis of the patients undergoing PPV from January 1999 to May 2010 for TRD and NCVH secondary to PDR recorded on an electronic patient record (provided with textbook Vitreoretinal Surgery, Springer)13 and case note review was performed. TRD was defined as elevated retina visible or detected on ultrasound preoperatively or if that was a predominant pathology found at the time of operation and included patients with combined rhegmatogenous and TRD. NCVH was defined as vitreous hemorrhage, which was persistent or recurrent requiring surgery, if pre-retinal membrane was discovered at surgery this was removed by delamination. All patients had 20-gauge 3 port PPV, without the use of chandelier illumination or bimanual surgery. ‘En bloc' dissection of neovascular membranes was performed without the segmentation of membranes. All primary surgery (first operation) was performed with the aim of avoidance of silicone oil tamponade with no tamponade or gas tamponade used as required. Phacoemulsification lens extraction at the time of PPV was only performed if there was cataract present preoperatively which might prevent visualization of the retina during surgery.

Data collected included baseline best-corrected visual acuity (VA), indication for the procedure, preoperative (pre-op) clinical data, per-op complications, outcome, and duration of follow-up. SPSS 17.0 (Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. VAs were converted to logMAR, and counting fingers, hand movements, perception of light, and no perception of light (NPL) were assigned values of 1.85, 2.3, 2.6, and 2.9 respectively.14, 15 The primary endpoints of the study were anatomical success defined as all retina flat and eyes with VA ≤0.3 logMAR (Snellen 6/12) at last follow-up. Iatrogenic retinal tear was defined as any retinal break created during surgery. The influence of baseline patient and peroperative characteristics (age, gender, type of diabetes, indication for surgery, grade of surgeon, peroperative complications) on risk of reoperation was analyzed using a linear regression model, and adjusted odds ratio (OR) were calculated. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05 for all the analyses.

The Institutional Review board and the Clinical Effectiveness Department of the hospital approved this study (CASS AP0861-01).

Results

Patient demographics

There were 346 eyes of 249 patients. The mean age of the population was 55.63 years (SD 15.83 years) with 42.07 years (SD 15.61) for type I diabetes and 60.41 years (SD 15.41) for type II. The indications for surgery did not differ statistically by diabetes type (Table 1).

Table 1. Patient demographics.

|

Indication |

Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VH | TRD | |||

| Type of diabetes | 1 | 45 | 62 | 107 |

| 2 | 120 | 119 | 239 | |

| Total | 165 | 181 | 346 | |

Cataract extraction

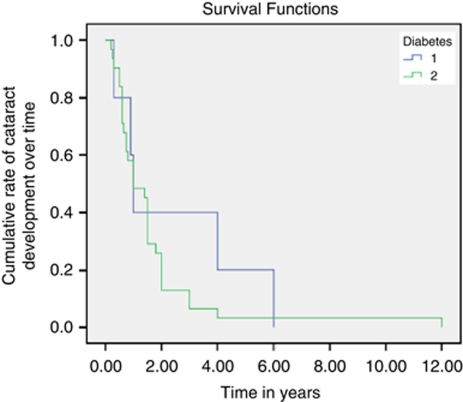

In our study 66/346 (19.07%) eyes had previous cataract extraction before presentation for primary vitrectomy. Over the 10 years 105/346 (30.34%) of eyes had combined cataract extraction and PPV. The range varied from 0 to 40% with no combined procedure in years 1999–2000 to a peak of 40% in 2001 and 2004, and a median of 31.3% of all primary vitrectomies having combined cataract extraction. The number of eyes having combined procedure did not vary with type of diabetes and indication for vitrectomy (χ2=10.80, P=0.461). Furthermore, 36/175 (20.57%) of the remaining eyes had cataract extraction after a mean interval of 1.75 years following primary vitrectomy. The mean interval from primary vitrectomy to cataract surgery was 2.4 years in eyes with type 1 diabetes and 1.6 years in eyes with type 2 diabetes (P<0.05, Figure 1). In patients with type 1 diabetes, only 60% had cataract surgery by 3 years following primary vitrectomy, whereas for type II diabetes, ∼50% had the operation by 1 year and 87.1% by 2 years.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve showing time in years to develop cataract following primary vitrectomy.

Anesthesia

Surgery was performed under general or local anesthesia. Local anesthesia involved mainly subtenon's 2% lignocaine with bupivacaine 0.25%, and also some peribulbar injections. Overall, 75.6% of the procedures were carried out under general anesthesia, but in 2009 alone 55.4% procedures were performed under local anesthesia. The χ2 test was significant (P=0.002), indicating that progressively more procedures were performed under general anesthesia than local anesthesia in advancing years. However, more patients with VH patients had surgery under local anesthesia than with TRD.

Other peroperative procedures

In all, 93.5% of patients received further laser therapy during their primary procedure. Use of tamponade agents is shown in Table 2. A total of 35 eyes (10.1%) required silicone oil tamponade at some stage during their surgical care (13 in the primary vitrectomy, 5.2% patients, and 22 during secondary vitrectomy). Sixty percent of these eyes had silicone oil in situ at last follow-up.

Table 2. Tamponade agents used in the operations.

| Indication for surgery (n=eyes) |

Tamponade agent |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nil | Air | SF6 | C3F8 | Silicone oil | |

| All (346) | 201 (58%) | 27 (7.7%) | 67 (19.2%) | 57 (16.4%) | 13 (3.7%) |

| NCVH (165) | 130 (78.8%) | 14 (8.5%) | 14 (8.5%) | 7 (4.2%) | 0 |

| TRD (181) | 60 (33.1%) | 13 (7.2%) | 49 (27 1%) | 46 (25.4%) | 13 (7.2%) |

Abbreviations: C3F8, perfluoropropane; NCVH, non-clearing vitreous hemorrhage; SF6, sulphur hexafluoride; TRD, tractional retinal detachment.

Peroperative complications

Overall, 104/346 (30.05%) of the eyes had iatrogenic retinal tear, with rates of 45.3% (82/181) and 12.7% (21/165) in the eyes going primary vitrectomy for TRD and NCVH, respectively. Using logistic regression analysis patients with TRD were more likely than those with NCVH to develop iatrogenic tear, P<0.001, OR: 5.68, 95% confidence interval (CI): (3.299–9.779). A total of 5/346 (1.4%) of the eyes had lens touch at some stage during vitrectomy. There were no peroperative choroidal hemorrhages.

Anatomical and visual outcome

In all, 95.3% of eyes had a flat retina at final follow-up of mean 1.44 (SD 1.88 years) (3–123 months with a median of 14 months). A total of 4.65% of the eyes had an area of detached retina at the time of last follow-up. The mean pre-op VA in NCVH and in TRD groups was 1.56 logMAR and 1.61 logMAR, respectively, that improved to mean postoperative (post-op) VA of 0.66 logMAR and 1.16 logMAR at last follow-up. Overall, 144/365 (39.4%) eyes had final VA of logMAR ≤0.3 (Snellen 6/12). One hundred and thirty six (37.3%) of the operated eyes had VA of logMAR ≥1.0 (Snellen 6/60) or worse and 218 (59.7%) of the operated eyes showed ≥0.3 logMAR improvement from baseline at last follow-up (Table 3). Paired sample two-tailed test revealed that VA increased significantly for all groups, collectively (P<0.01) and individually by indications: TRD (P<0.001) and NCVH (P<0.001). Overall 6.01% (15/249) of all patients were registered as severely visual impaired (Snellen <6/60 in both eyes) at last follow-up.16

Table 3. Visual and anatomical outcome in eyes with diabetic vitrectomy in each year.

| Year (number of eyes, n) | Final retina attached (%) | % Final VA logMAR ≥1.0 (Snellen 6/60) | % Eyes final VA logMAR ≤0.3 (Snellen 6/12) | % Eyes ≥0.3 logMAR improvement from baseline |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 (2) | 100 | 50 | 50 | 0 |

| 2000 (6) | 100 | 33 | 50 | 66 |

| 2001 (25) | 92 | 46 | 15 | 54 |

| 2002 (32) | 97 | 37 | 41 | 68 |

| 2003 (44) | 89 | 57 | 23 | 57 |

| 2004 (50) | 100 | 40 | 34 | 60 |

| 2005 (37) | 100 | 33 | 36 | 61 |

| 2006 (30) | 90 | 30 | 51 | 50 |

| 2007 (47) | 98 | 38 | 46 | 66 |

| 2008 (37) | 90 | 31 | 43 | 51 |

| 2009 (34) | 100 | 22 | 57 | 73 |

| 2010 (3) | 100 | 0 | 75 | 0 |

Abbreviations: logMAR, logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution; VA, visual acuity.

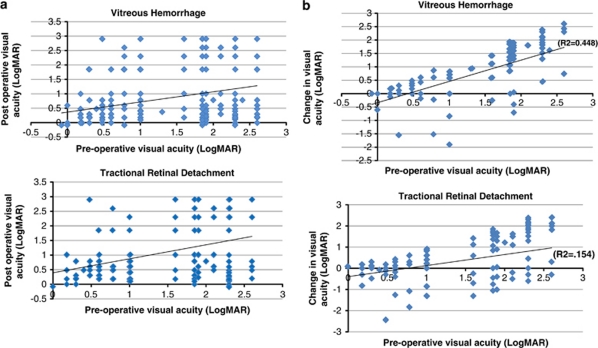

Spearman's rank correlation revealed that both pre-op VA (P=0.047) and final post-op VA (P<0.001) improved significantly with each year but the difference between pre-op and post-op VA did not change significantly over time (Table 4). Patients with worse pre-op had poorer final post-op VA (Figure 2a) but eyes in general with worse pre-op VA see greater visual improvement from the baseline in the TRD and NCVH groups (Figure 2b). For NCVH, the correlation between pre-op and post-op is r=0.227, P=0.003; for TRD, the correlation between pre-op and post-op is also significant, r=0.365, P<0.001.

Table 4. Spearman rank correlation between change in pre-op and post-op VA with time.

| Spearman's rho (ρ) | Pre-op VA (logMAR) | Post-op VA (logMAR) | VA improvement | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operation date | Correlation Coefficient | −0.104 P=0.047 | −0.196 P<0.001 | −0.074 NS |

| Pre-opVA (logMAR) | Correlation Coefficient | 0.295 P<0.001 | −0.485 P<0.001 |

Abbreviation: VA, visual acuity.

Figure 2.

Scatter plot showing relation between (a) pre-op and post-op visual acuity by indication, (b) change in visual acuity vs pre-op visual acuity by indication.

Reoperation by indication

Post vitrectomy hemorrhage

For the purpose of study, the post vitrectomy hemorrhages requiring surgery were divided into two groups: (a) early: surgery within first 3 months following primary vitrectomy and (b) late: surgery after first 3 months following primary vitrectomy. Overall 86/346 (24.4%) of the eyes had vitreous hemorrhage following primary vitrectomy and 32/346 (9.2%) of the eyes warranted reoperation for NCVH. In total, 25% of these operation were early within first 3 months and 75% late. Median time for reoperation in late vitreous hemorrhage was 6 months.

Retinal detachment

Overall, 35/346 (10.1%) of the eyes had reoperation for retinal detachment. The indication for primary vitrectomy in theses eyes were TRD in 31/181 (17.1%) and NCVH in 4/165 (2.4%), respectively. In the study 22/35 (62.8%) of these eyes required silicone oil and 15% of the eyes required >1 reoperation (PPV) to stabilize the retina. In all, 20/104 (19.2%) of the eyes with iatrogenic breaks developed redetachment that required reoperation and this was a risk factor for the development of post-op retinal detachment, P=0.0002, OR: 3.90 (95% CI: 1.91–7.97).

Other indications for reoperation

Overall, 2/36 (5.5%) eyes had dropped nucleus during subsequent cataract extraction in previously vitrectomised eyes that was succesfully managed with vitrectomy and intraocular lens implantation.

Glaucoma

New glaucoma requiring topical medication developed in 16/346 (4.6%). of the eyes with 2 of these 16 eyes requiring cyclodiode surgery. Overall, 2/16 of the eyes had neovascular glaucoma and 12/16 developed primary open angle and 1/16 developed pupillary block glaucoma.

Other

Other complications included submacular hemorrhage in one eye and phthisis in five eyes. One eye developed anterior segment ischemic syndrome.

Discussion

Anatomical and visual outcomes are quite often unpredictable in vitrectomy for PDR. Anatomical results are often limited by the extent and degree of fibrous tissue,17 vitreoretinal adhesion,17 and high rates of iatrogenic tears, which complicate the surgery.18, 19 Some of these eyes require silicone oil as a primary endo-tamponade to achieve stable retina at the time of primary vitrectomy. Functional visual outcome are also limited due to severe macular dysfunction from a long duration of macular traction and preceding ischemic maculopathy.18, 20, 21

In our series, 27.6% eyes with TRD and 50.9% with NCVH achieved final VA of ≤0.3 logMAR. This represents an improvement from DRVS study where 25% achieved ≤0.3 LogMAR following vitrectomy for VH12 and other reported studies reporting visual outcome in TRD.19, 20 There was an increase in the number of eyes with good visual outcomes and reduction in the number with very poor outcomes—approximately 25% of the DRVS eyes were NPL at last follow-up. These improved results could be attributed to improvement in surgical techniques and instrumentation, and hence diabetic vitrectomy getting safer, surgeons operating earlier as they become more confident, and possible early detection of severe sight threatening disease through screening programs. These programs are well established in United Kingdom and provide uptake (http://www.retinalscreening.nhs.uk) of up to 78% in most regional screening program. Also it could be due to improved control in diabetes and systemic co-morbidities after the lessons learned from DCCT study.22

Pre-op VA improved with time suggesting a move to earlier intervention, and this correlated with improved post-op visual results. Patients with worse pre-op visual acuities achieved greater improvement in logMAR but had worse relative post-op VA. Although poor pre-op VA is related to final VA, other factors like degree and density of associated VH may affect the pre-op vision. The early vitrectomy study23, 24 suggested that the results of surgery were better with earlier vitrectomy. The surgical method has changed significantly since the EVS and there could be a justification for repeating that study with modern methods. Both the EVS and our study suggest earlier intervention is preferable, because of the better outcomes from surgery performed more quickly after presentation.

In patients with hazy media due to cataract, combined phaco-vitrectomy procedures offer the benefit of a clear surgical view.25 However, it is important to be cautious performing combined procedures as the incidence of cataract formation is lower after diabetic vitrectomy, particularly in younger patients.26 In addition, the rate of anterior segment complications is higher in PPV for diabetes27 and loss of accommodation more handicapping in these young patients especially considering that patients with NCVH had a mean age of 42 years. The suspected low conversion of diabetic patients to cataract surgery post vitrectomy is supported by this study. The cause of the low rate of post-op cataract surgery in diabetes is uncertain but may be due to the relatively young age of some patients or to relative ischemia of the eye.28 It may be preferable to defer cataract surgery in diabetics until a visually significant cataract has developed.29 Previously vitrectomized eyes carry a risk of posterior capsular tear (9%) and dropped nucleus as reported by Sziarto et al in the study of 143 eyes, and it was 2/31 (6.4%) in the current study.

In many parts of the world, silicon oil is a favoured method of tamponade for diabetic vitrectomy both to avoid loss of vision from rebleeds and to maintain long-term tamponade in TRD. The surgical approach in this study was to avoid silicone oil tamponade in the primary procedure where possible and this was reflected in the high use of various gas tamponades and low use of oil. This was consistent with the maintenances of good anatomical and visual results, and avoids the need of further resurgery, prevents neuropathic and phototoxic effect of light in eye with previous diabetic maculopathy due long-term silicon tamponade.31, 32, 33, 34 The surgical approach was uncompromisingly to remove epiretinal membranes and this was likely to be the cause of the high rates of iatrogenic breaks seen especially in TRD surgery. In addition, our institution has a training program with ∼50% of operations performed by trainees in vitreoretinal surgery under supervision. Iatrogenic break was associated with an increase in post-op retinal detachment and therefore methods to minimize these retinal tears may improve outcomes. New techniques involving bimanual surgery35 (not used in this study) should be investigated for improved rates of iatrogenic tear creation and improved surgical outcomes. The 23-gauge vitrectomy and anti-VEGF adjuvant before surgery36 also require further assessment.

To summarize, surgical management of the late complications of PDR remains a common but challenging vitreoretinal procedure and the visual results remain uncertain in many patients. The surgical outcome after diabetic vitrectomy has continued to improve with advances in vitreoretinal surgical instrumentation and technique. There was a gradual adjustment with time to operate on patients with better vision over the 10-year period and this was associated with better visual outcomes.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

BG and RW were involved in ethics approval, data collection, analysis, and manuscript preparation. THW and SS were involved in the study design, final editing, approval of the manuscript and study.

References

- Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care. 2004;27 (5:1047–1053. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diabetes Health Intelligence APHO Diabetes Prevalence Model: Key Findings for England Diabetes Health Intelligence; 2010 ( www.yhpho.org.uk ). [Google Scholar]

- Resnikoff S, Pascolini D, Etya'ale D, Kocur I, Pararajasegaram R, Pokharel GP, et al. Global data on visual impairment in the year 2002. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82 (11:844–851. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunce C, Wormald R. Causes of blind certifications in England and Wales: April 1999-March 2000. Eye (Lond) 2008;22 (7:905–911. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein R, Klein BE, Moss SE. The Wisconsin epidemiological study of diabetic retinopathy: a review. Diabetes Metab Rev. 1989;5 (7:559–570. doi: 10.1002/dmr.5610050703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leske MC, Wu SY, Hyman L, Li X, Hennis A, Connell AM, et al. Diabetic retinopathy in a black population: the Barbados Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 1999;106 (10:1893–1899. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(99)90398-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall V, Thomsen RW, Henriksen O, Lohse N. Diabetes in Sub Saharan Africa 1999-2011: epidemiology and public health implications. a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:564. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine SL, Patz A. Ten years after the Diabetic Retinopathy Study. Ophthalmology. 1987;94 (7:739–740. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(87)33523-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn HW, Jr, Chew EY, Simons BD, Barton FB, Remaley NA, Ferris FL., III Pars plana vitrectomy in the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study ETDRS report number 17. Ophthalmology. 1992;99 (9:1351–1357. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(92)31779-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DF, Williams GA, Hartz A, Mieler WF, Abrams GW, Aaberg TM. Results of vitrectomy for diabetic traction retinal detachments using the en bloc excision technique. Ophthalmology. 1989;96 (6:752–758. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(89)32813-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Da Mota SE, Nunez-Solorio SM. Experience with intravitreal bevacizumab as a preoperative adjunct in 23-G vitrectomy for advanced proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2010;20 (6:1047–1052. doi: 10.1177/112067211002000604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Diabetic Retinopathy Vitrectomy Study Research Group Early vitrectomy for severe vitreous hemorrhage in diabetic retinopathy. Two-year results of a randomized trial Diabetic Retinopathy Vitrectomy Study report 2. Arch Ophthalmol. 1985;103 (11:1644–1652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson TH. Vitreoretinal Surgery. Secaucus: NJ, Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Holladay JT. Proper method for calculating average visual acuity. J Refract Surg. 1997;13 (4:388–391. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-19970701-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze-Bonsel K, Feltgen N, Burau H, Hansen L, Bach M. Visual acuities ‘hand motion' and ‘counting fingers' can be quantified with the freiburg visual acuity test. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47 (3:1236–1240. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Screening Committee Service Objectives and Quality Assurance Standards National Screening Committee; 2009. Report no: Release 6.5 ( ( www.retinalscreening.nhs.uk ). [Google Scholar]

- Eliott D, Lee MS, Abrams GW. Proliferative diabetic retinopathy: principles and techniques of surgical treatment. Retina. 2006. pp. 2413–2449.

- Schrey S, Krepler K, Wedrich A. Incidence of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment after vitrectomy in eyes of diabetic patients. Retina. 2006;26:149–152. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200602000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yorston D, Wickham L, Benson S, Bunce C, Sheard R, Charteris D. Predictive clinical features and outcomes of vitrectomy for proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92:365–368. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.124495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DF, Williams GA, Hartz A, Mieler WF, Abrams GW, Aaberg TM. Results of vitrectomy for diabetic traction retinal detachments using the en bloc excision technique. Ophthalmology. 1989;96:752–758. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(89)32813-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SA, Butler JB, Myers FL, Bresnick GH. Pars plana vitrectomy. Treatment for tractional macula detachment secondary to proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1980;98:659–664. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1980.01020030653001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DCCT (The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group) The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1993;329 (14:977–986. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Diabetic Retinopathy Vitrectomy Study Research Group Early vitrectomy for severe proliferative diabetic retinopathy in eyes with useful vision. Results of a randomized trial--Diabetic Retinopathy Vitrectomy Study Report 3. Ophthalmology. 1988;95 (10:1307–1320. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(88)33015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Diabetic Retinopathy Vitrectomy Study Research Group Early vitrectomy for severe proliferative diabetic retinopathy in eyes with useful vision Clinical application of results of a randomized trial-Diabetic Retinopathy Vitrectomy Study Report 4. Ophthalmology. 1988;95 (10:1321–1334. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(88)33014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey JM, Francis RR, Kearney JJ. Combining phacoemulsification with pars plana vitrectomy in patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy: a series of 223 cases. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1335–1339. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00454-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smiddy WE, Feuer W. Incidence of cataract extraction after diabetic vitrectomy. Retina. 2004;24:574–581. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200408000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treumer F, Bunse A, Rudolf M, Roider J. Pars plana vitrectomy, phacoemulsification and intraocular lens implantation. Comparison of clinical complications in a combined versus two-step surgical approach. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;244:808–815. doi: 10.1007/s00417-005-0146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holekamp NM, Bai F, Shui YB, Almony A, Beebe DC. Ischemic diabetic retinopathy may protect against nuclear sclerotic cataract. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;150 (4:543–550. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott ML, Puklin JE, Abrams GW, Eliott D. Phacoemulsification for cataract following pars plana vitrectomy. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 1997;28:558–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szijarto Z, Haszonits B, Biro Z, Kovacs B. Phacoemulsification on previously vitrectomized eyes: results of a 10-year-period. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2007;17 (4:601–604. doi: 10.1177/112067210701700419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazabon S, Groenewald C, Pearce IA, Wong D. Visual loss following removal of intraocular silicone oil. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89 (7:799–802. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.053561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert EN, Liew SH, Williamson TH. Visual loss after silicone oil removal. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89 (12:1667–1668. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.082610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newsom RS, Johnston R, Sullivan P, Aylward B, Holder G, Gregor Z. Visual loss following silicone oil removal. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89 (12:1668. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.082644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rani PK, Raman R, Bhende P, Sharma T. Visual loss may be due to silicone oil tamponade effect rather than silicone oil removal. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89 (12:1667. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.082602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz RL, Grizzard WS, Hammer ME. Vitrectomy for diabetic traction retinal detachment using the multiport illumination system. Ophthalmology. 2002;109 (12:2303–2307. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01291-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arevalo JF, Wu L, Sanchez JG, Maia M, Saravia MJ, Fernandez CF, et al. Intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) for proliferative diabetic retinopathy: 6-months follow-up. Eye (Lond) 2009;23 (1:117–123. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]