Abstract

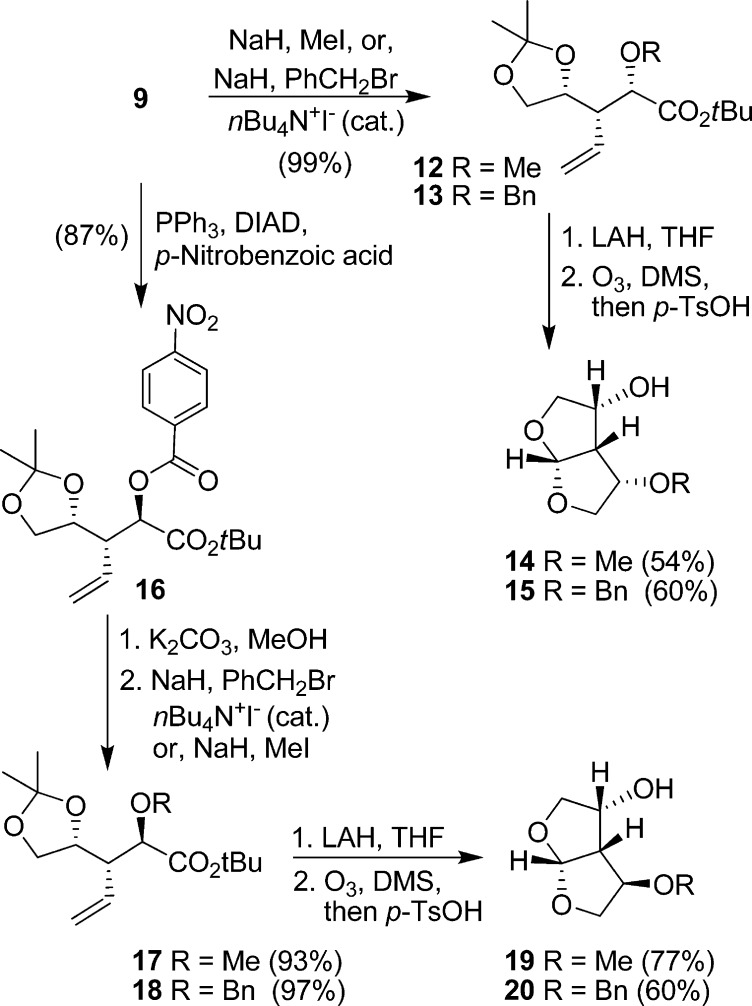

We investigated substituted bis-THF-derived HIV-1 protease inhibitors in order to enhance ligand-binding site interactions in the HIV-1 protease active site. In this context, we have carried out convenient syntheses of optically active bis-THF and C4-substituted bis-THF ligands using a [2,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement as the key step. The synthesis provided convenient access to a number of substituted bis-THF derivatives. Incorporation of these ligands led to a series of potent HIV-1 protease inhibitors. Inhibitor 23c turned out to be the most potent (Ki = 2.9 pM; IC50 = 2.4 nM) among the inhibitors. An X-ray structure of 23c-bound HIV-1 protease showed extensive interactions of the inhibitor with the protease active site, including a unique water-mediated hydrogen bond to the Gly-48 amide NH in the S2 site.

Keywords: HIV-1 protease inhibitors, Darunavir, bis-THF, drug-resistant, design, synthesis, X-ray structure

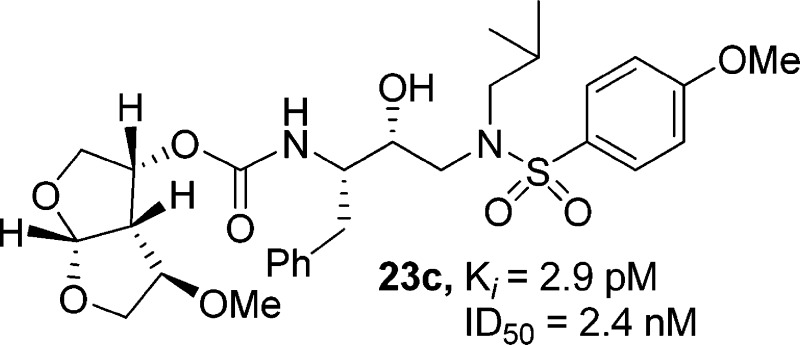

In our continuing studies aimed at the design and synthesis of novel HIV-1 protease inhibitors to combat drug resistance, we have developed a variety of exceedingly potent inhibitors.1 One of these inhibitors, darunavir (1, Ki = 16 pM, antiviral IC50 = 4.1 nM, Figure 1) was first approved in June 2006 for the treatment of HIV/AIDS patients harboring drug-resistant HIV-1 variants.2 Later, darunavir received an expanded approval for the treatment of all therapy-naïve HIV/AIDS patients, including pediatric patients.3 Darunavir incorporates a stereochemically defined (3R,3aS,6aR)-bis-tetrahydrofuranyl (bis-THF) urethane as the P2 ligand in a (R)-hydroxyethyl sulfonamide isostere.4 Structural studies of darunavir documented that the bis-THF ligand is involved in a network of hydrogen bonding interactions with the protein-backbone of the HIV-1 protease, as formulated in our “backbone binding” concept.5 A number of other clinical protease inhibitors (2, Brecanavir; 3, GS-8374) have also incorporated this bis-THF ligand and demonstrated marked antiviral potency against a panel of multidrug-resistant HIV-1 variants.6,7

Figure 1.

Structures of protease inhibitors 1−3.

In our continuing studies toward maximizing ligand-binding site interactions, based upon the X-ray structure of 1-bound HIV-1 protease, we further speculated that the incorporation of an alkoxy substituent at the C4-position of bis-THF could lead to new interactions with the backbone NH of Gly-48. We therefore required a stereoselective synthesis that would provide access to C4-substituted bis-THF derivatives for further optimization. The bis-THF ligand contains three contiguous stereogenic centers. A number of syntheses of the bis-THF ligand have been reported, including several optically active routes from our research group.8−12 Quaedflieg and co-workers reported a chiral synthesis that involved a conjugate addition of nitromethane.13 Other syntheses have been attempted with the use of various catalysts to obtain the desired product.14 Interestingly, many of these syntheses require late-stage resolution to obtain the enantiomerically pure ligand. Furthermore, the reported syntheses are not convenient for the preparation of C4-substituted derivatives. In view of this shortcoming, we investigated a new optically active synthesis utilizing an efficient [2,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement as the key step and an inexpensive chiral precursor as the starting material. The synthetic route provided convenient access to optically active bis-THF and functionalized bis-THF ligands. We incorporated these ligands in the hydroxyethylsulfonamide isostere, and the resulting HIV-1 protease inhibitors were evaluated in enzyme inhibitory and antiviral assays.

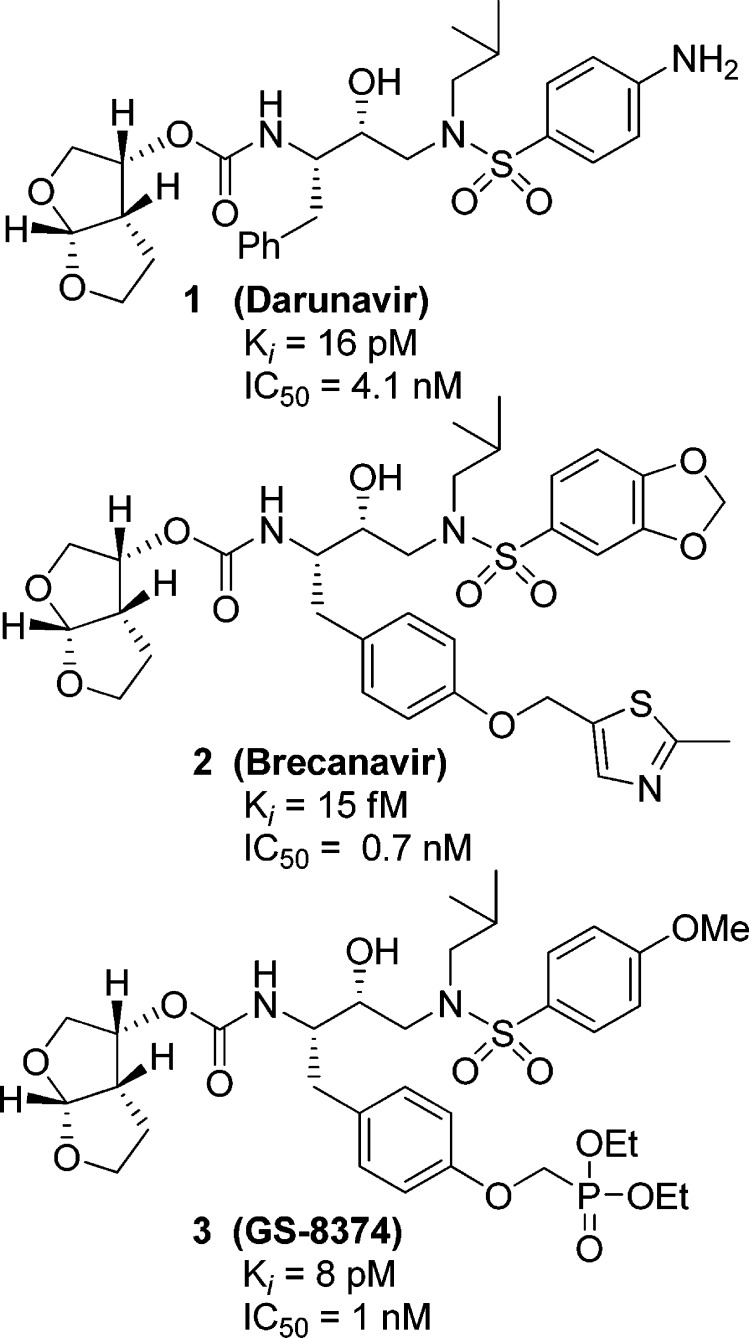

The synthesis of the bis-THF ligand started with known compound 4.11 It was prepared in multigram quantities by Wittig olefination of (S)-glyceraldehyde acetonide with (ethoxycarbonylmethylene) triphenylphosphorane, as described previously.11 The requisite (S)-glyceraldehyde can be obtained from ascorbic acid,15,16l-arabinose,17l-serine,18 and l-tartaric acid,19 as reported. We used the l-tartaric acid-derived procedure for our synthesis. Dibal-H reduction of 4 resulted in alcohol 5 (Scheme 1).20,21

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Bis-THF Ligand 11.

We investigated the O-alkylation of 5 using tert-butyl bromoacetate 6 under a variety of conditions. The use of KOtBu in THF at 23 °C for 2 h resulted in a single product, 7 in 56% yield. O-alkylation, using Cs2CO3 in DMF also proceeded with a moderate yield (59%). However, the use of CsOH−H2O and activated molecular sieves, in the presence of tetrabutylammonium iodide in acetonitrile, provided the best results.22 These conditions afforded the desired O-alkylated product 7 in 85% yield. Only a small amount of the transesterification product (<5%) and a small amount (<5%) of starting material were recovered in this reaction.

We then investigated a [2,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement of 7 under a variety of conditions. Reaction of 7 with KOtBu at 23 °C proceeded smoothly but provided 9 a 4:1 diastereoselective ratio at the C2-chiral center. Lowering the temperature to −10 °C resulted in a marked increase in selectivity (17:1) with a moderate yield (63%). It should be noted that the C2-chiral center would be eliminated en route to the bis-THF ligand; however, stereoselectivity is important for the synthesis of C4-derivatives. Reactions with LiHMDS in THF at −20 °C provided 9 in 55% yield and 6:1 diastereoselectivity. However, the same reaction at −40 °C to −30 °C for 1 h provided the best yield. Diastereomer 9 was obtained as a single product in 80% yield. The stereochemical outcome of the [2,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement can be rationalized by the proposed transition-state model 8, in which the allylic C−O bond is orthogonal to the plane of the allylic C=C and is antiperiplanar with respect to the approaching carbanion, as described by Bruckner and co-workers.23 For the synthesis of the bis-THF ligand, alcohol 9 was converted to the corresponding mesylate. LAH reduction of the mesylate provided alcohol 10 in 74% yield, over 2 steps. Oxidative cleavage of the terminal alkene followed by acid-catalyzed cyclization, in the presence of a catalytic amount of p-TsOH in CHCl3 at reflux, afforded the bis-THF alcohol 11 in 80% yield.

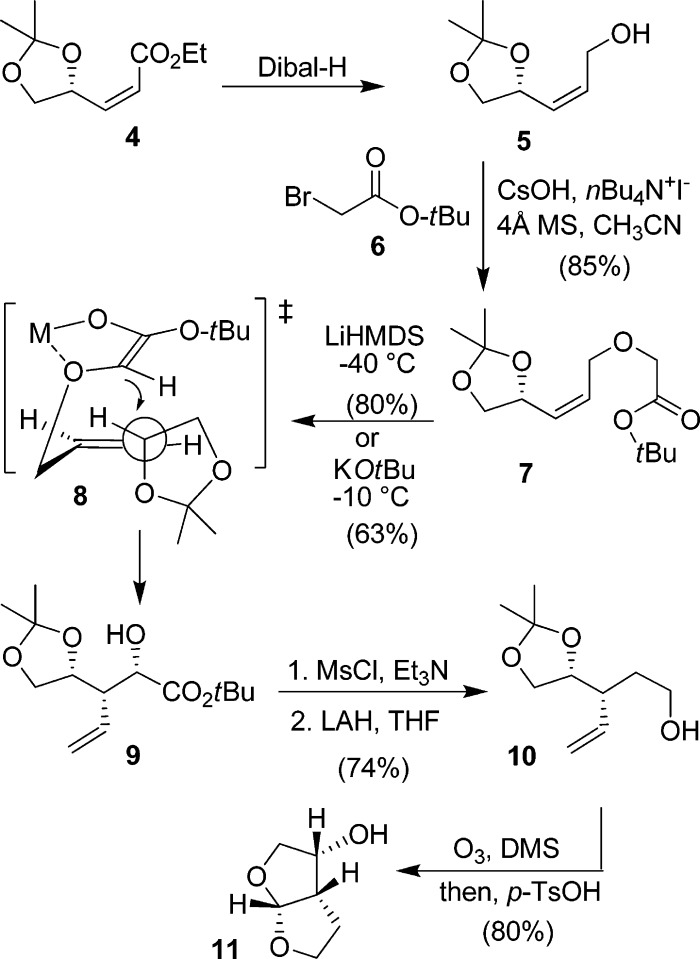

As shown in Scheme 2, rearrangement product 9 was utilized for the synthesis of C4-substituted bis-THF ligands. Alcohol 9 can be conveniently functionalized into derivatives which can further interact with the HIV-1 protease backbone atoms. Thus, protection of the free hydroxyl group provided methyl and benzyl ethers 12 and 13, respectively. LAH reduction, followed by ozonolysis, and acid-catalyzed cyclization resulted in compounds 14 and 15, respectively. Inversion of the C2-hydroxyl group of 9 using Mitsunobu’s protocol24 gave 16 in 87% yield. Selective deprotection of the nitro benzoate with potassium carbonate in methanol at 0 °C, and subsequent protection with methyl iodide or benzyl bromide provided methyl and benzyl ethers 17 and 18, respectively. LAH reduction, ozonolysis, and cyclization resulted in the desired substituted bis-THF ligands 19 and 20.

Scheme 2. Syntheses of Substituted Bis-THF Ligands.

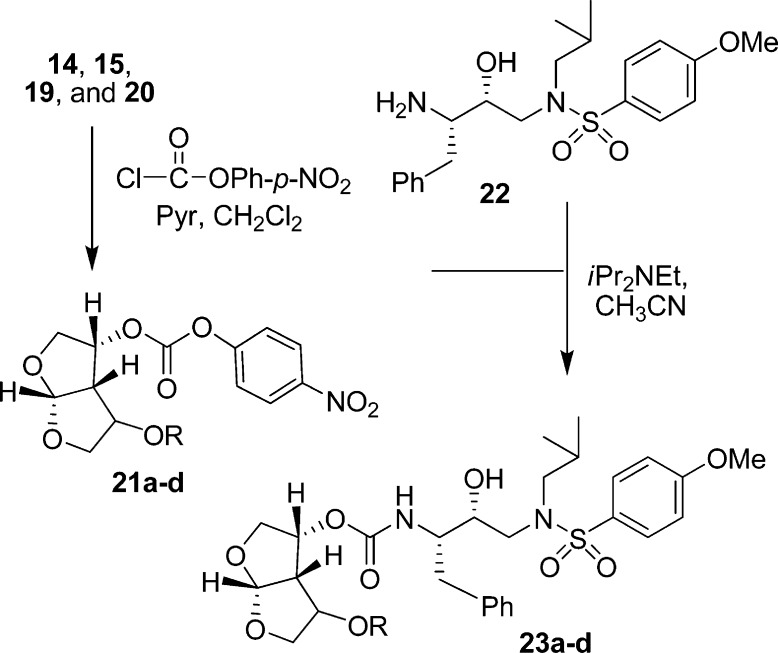

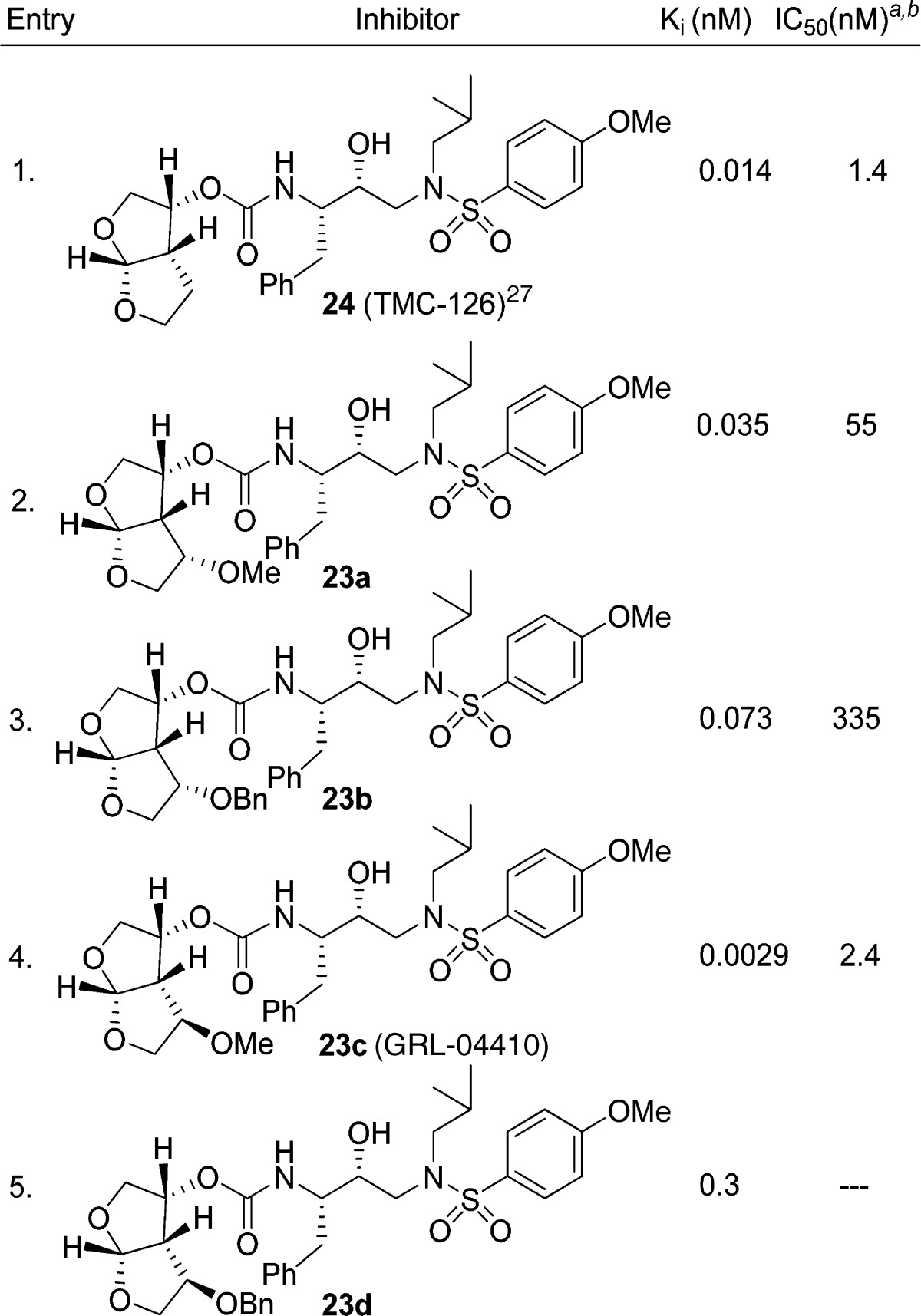

As shown in Scheme 3, alcohols 14, 15, 19, and 20 were activated with p-nitrophenyl chloroformate to provide mixed activated carbonates 21a−d. These carbonates were reacted with amine 22 to afford HIV-1 protease inhibitors 23a−d.8 These inhibitors were all evaluated for their activity in both enzyme inhibitory and antiviral assays. The results are shown in Table 1. The enzyme inhibitory activity (Ki) was determined according to an assay protocol reported by Toth and Marshall.25 The inhibitors displayed extremely potent enzyme inhibitory activity. Compound 23c (Ki = 0.0029 nM) is the most potent compound in this series. Its diastereomer 23a (Ki = 0.035 nM) displayed a loss in enzyme inhibitory activity. The benzyl derivatives 23b and 23d have also shown reduced enzyme activity. Antiviral IC50 values were determined using the MTT assay.26,27 Consistent with its enzyme inhibitory potency, inhibitor 23c exhibited an impressive antiviral activity (IC50 = 2.4 nM).

Scheme 3. Syntheses of Protease Inhibitors.

Table 1. Structure and Activity of Inhibitors.

|

Values are means of at least three experiments.

Human T-lymphoid (MT-2) cells were exposed to 100 TCID50 values of HIV-1LAI and cultured in the presence of each PI, and IC50 values were determined using the MTT assay.

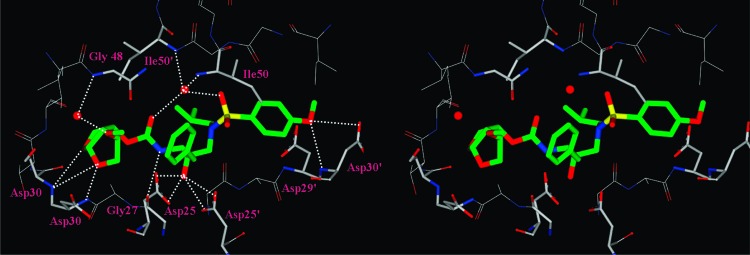

To gain molecular insights into ligand-binding site interactions responsible for the potent antiviral activity of inhibitor 23c, we have determined an X-ray crystal structure of GRL-04410 (23c) complexed with the wild-type protease. The structure was refined to an R-factor of 0.175 at a high resolution of 1.40 Å. The structure comprises the protease dimer and inhibitor in two orientations related by a 180° rotation, with 55/45 relative occupancies (pdb code: 3QAA). The protease dimer structure is essentially identical to that in the protease−darunavir complex with a rmsd of 0.14 Å on the Cα atoms.28 The inhibitor interactions in the active site cavity consist of a series of hydrogen bonds and weaker CH···O interactions, as described previously for darunavir and GRL-09865.28,29 The critical differences are provided by the methoxy group on the bis-THF ligand in 23c. As shown in Figure 2, the methoxy oxygen forms a water-mediated hydrogen bond with the amide NH of Gly-48. Furthermore, the methyl group forms a CH···O interaction with the carbonyl oxygen of Gly-48 that could stabilize the conformation of the flexible flaps. The flexibility of the flaps is important for the binding of substrates or inhibitors and for the catalytic activity of HIV protease. The flap conformation and flexibility can be altered by sequence polymorphisms and drug resistant mutations.30−32 Consequently, inhibitors such as 23c with strong flap interactions are expected to retain high affinity for drug resistant variants of the protease.

Figure 2.

Stereoview of the X-ray structure of inhibitor 23c (green)-bound HIV-1 protease (pdb code: 3QAA). All strong hydrogen bonding interactions are shown as dotted lines.

In conclusion, we investigated C4-alkoxy substituted bis-THF-derived HIV-1 protease inhibitors in order to enhance ligand-binding site interactions in the HIV-1 protease active site. In this context, we have developed an optically active synthesis of the bis-THF and C4-substituted bis-THF ligands using a [2,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement as the key step. Incorporation of C4-substituted bis-THF ligands resulted in a series of highly potent HIV protease inhibitors. Compound 23c is remarkably potent (Ki = 2.9 pM; IC50 = 2.4 nM). The stereochemical importance of the methoxy substituent is evident, as the corresponding epimer is significantly less potent. A protein−ligand X-ray structure of 23c-bound HIV-1 protease revealed extensive interactions of the inhibitor in the active site of HIV-1 protease. It maintained all key backbone hydrogen bonding interactions similar to those of darunavir. Of particular importance, the methoxy oxygen on the bis-THF ligand is involved in a unique water-mediated hydrogen bond to the Gly-48 amide NH. Further design and ligand optimization involving this interaction is in progress.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff at the Southeast Regional-Collaborative Access Team (SER-CAT) at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory, for assistance during X-ray data collection. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. W-31-109-Eng-38. We thank Drs. K. V. Rao and Bruno Chapsal (Purdue University) for helpful discussions.

Supporting Information Available

Experimental procedures and 1H- and 13C-NMR spectral data for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Financial support by the National Institutes of Health (GM 53386, A.K.G.; GM 062920, I.T.W.) is gratefully acknowledged. This work was also supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, and in part by a Grant-in-aid for Scientific Research (Priority Areas) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (Monbu Kagakusho) and a Grant for Promotion of AIDS Research from the Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Labor of Japan.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Ghosh A. K. Harnessing Nature’s Insight: Design of Aspartyl Protease Inhibitors from Treatment of Drug-Resistant HIV to Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 2163–2176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FDA approves Darunavir on June 23, 2006: FDA approved a new HIV treatment for patients who do not respond to existing drugs. Please see http://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/NEWS/2006/NEW01395.html.

- On October 21, 2008, FDA granted traditional approval to Prezista (darunavir), coadministered with ritonavir and with other antiretroviral agents, for the treatment of HIV-1 infection in treatment-experienced adult patients. In addition, a new dosing regimen for treatment-naïve adult patients was approved.

- Ghosh A. K.; Sridhar P. R.; Kumaragurubaran N.; Koh Y.; Weber I. T.; Mitsuya H. A Privileged Ligand for Darunavir and a New Generation of HIV-Protease Inhibitors That Combat Drug-Resistance. ChemMedChem 2006, 1, 939–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A. K.; Chapsal B. D.; Weber I. T.; Mitsuya H. Design of HIV Protease Inhibitors Targeting Protein Backbone: An Effective Strategy for Combating Drug Resistance. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 78–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J. F.; Andrews C. W.; Brieger M.; Furfine E. S.; Hale M. R.; Hanlon M. H.; Hazen R. J.; Kaldor I.; McLean E. W.; Reynolds D.; Sammond D. M.; Spaltenstein A.; Tung R.; Turner E. M.; Xu R. X.; Sherrill R. G. Ultra-potent P1 modified arylsulfonamide HIV protease inhibitors: The discovery of GW0385. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 1788–1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilar T.; He G.-X.; Kiu X.; Chen J.; Hatada M.; Swaminathan S.; McDermott M. J.; Yang Z.-Y.; Mulato A. S.; Chen X.; Leavitt S. A.; Stray K. M.; Lee W. A. Suppression of HIV-1 Protease Inhibitor Resistance by Phosphonate-mediated Solvent Anchoring. J. Mol. Biol. 2006, 363, 635–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A. K.; Martyr C. D. Darunavir (Prezista): A HIV-1 Protease Inhibitor for Treatment of Multidrug-Resistant HIV; Li J. J., Johnson D. S., Eds.; In Modern Drug Synthesis; Wiley: Hoboken, New Jersey, 2010; pp 29−44. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A. K.; Chen Y. Synthesis and Optical Resolution of High Affinity P2-Ligands for HIV-1 Protease Inhibitors. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995, 36, 505–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A. K.; Kincaid J. F.; Walters D. E.; Chen Y.; Chaudhuri N. C.; Thompson W. J.; Culberson C.; Fitzgerald P. M. D.; Lee H. Y.; McKee S. P.; Munson P. M.; Duong T. T.; Darke P. L.; Zugay J. A.; Schleif W. A.; Axel M. G.; Lin J.; Huff J. R. Nonpeptidal P2-Ligands for HIV Protease Inhibitors: Structure-Based Design, Synthesis and Biological Evaluations. J. Med. Chem. 1996, 39, 3278–3290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A. K.; Leshchenko S.; Noetzel M. Stereoselective Photochemical 1,3-Dioxolane Addition to α,β Unsaturated-γ-lactone: Synthesis of Bis-tetrahydrofuranyl Ligand for HIV Protease Inhibitor UIC-94-017 (TMC-114). J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 7822–7829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A. K.; Li J.; Perali R. S. A Stereoselective Anti-aldol Route to (3R,3aS,6aR)-Tetrahydro-2H-furo[2,3-b]furan-3-ol: A Key Ligand for a New Generation of HIV Protease Inhibitors. Synthesis 2006, 3015–3018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quaedflieg P. J. L. M.; Kesteleyn B. R. R.; Wigerinck P. B. T. P.; Goyvaerts N. M. F.; Jan Vijn R.; Liebregts C. S. M.; Kooistra J. H. M. H.; Cusan C. Stereoselective and Efficient Synthesis of (3R,3aS,6aR)-Hexahydrofuro[2,3-b]furan-3-ol. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 5917–5920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black D. M.; Davis R.; Doan B. D.; Lovelace T. C.; Millar A.; Toczko J. F.; Xie S. Highly diastereo- and enantioselective catalytic synthesis of the bis-tetrahydrofuran alcohol of Brecanavir and Darunavir. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2008, 19, 2015–2019. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G. C.; Crawford T. C.; Bacon B. E. Stereoselective, catalytic reduction of l-ascorbic acid: a convenient synthesis of l-gulono-1,4-lactone. J. Org. Chem. 1981, 46, 2977–2979. [Google Scholar]

- Hubschwerlen C.; Specklin J.-L.; Higelin J.. l-(S)-Glyceraldehyde Acetonide. Organic Syntheses; Wiley & Sons: New York, 1998; Coll Vol. No. IX, p 454. [Google Scholar]

- Maloneyhuss K. E. A Useful Preparation of l-(S)-Glyceraldehyde Acetonide. Synth. Commun. 1985, 15, 273–277. [Google Scholar]

- Hirth G.; Walther W. Synthesis of the (R)- and (S)-Glycerol Acetonides. Determination of the Optical Purity. Helv. Chim. Acta 1985, 68, 1863–1871. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hakim A. H.; Haines A. H.; Morley C. Synthesis of 1,2-O-Isopropylidene-l-threitol and its Conversion to (R)-1,2-O-Isopropylideneglycerol. Synthesis 1985, 2, 207–208. [Google Scholar]

- Mann J.; Weymouth-Wilson A. C.. Photoinduced-Addition of Methanol to (5S)-(5-O-tert-Butyldimethylsiloxymethyl)Furan-2(5H)-one: (4R,5S)-4-Hydroxymethyl-(5-O-tert-Butyldimethyl siloxymethyl) Furan-2(5H)-one. Organic Syntheses; Wiley & Sons: New York, 2004; Collect. Vol. No. X, p 152; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Borcherding D. R.; et al. Potential inhibitors of S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferases. Molecular dissections of neplanocin A as potential inhibitors of S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase. J. Med. Chem. 1988, 31, 1729–1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dueno E. E.; Chu F.; Kim S.-I.; Jung K. W. Cesium promoted O-alkylation of alcohols for the efficient ether synthesis. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999, 40, 1843–1846. [Google Scholar]

- Brückner R.; Priepke H. Asymmetric Induction in the [2,3]-Wittig Rearrangement by Chiral Substituents in the Allyl Moiety. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1988, 27, 278–280. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge J. A.; Nissen J. S.; Presnell M.. A General Procedure for Mitsunobu Inversion of Sterically Hindered Alcohols: Inversion of Menthol. (1S,2S,5R)-5-Methyl-2-(1-Methylethyl)Cyclohexyl 4-Nitrobenzoate. Organic Syntheses; Wiley & Sons: New York, 1998; Collect. Vol. No. IX, pp 607−611. [Google Scholar]

- Toth M. V.; Marshall G. R. A simple, continuous fluorometric assay for HIV protease. Int. J. Pept. Protein Res. 1990, 36, 544–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh Y.; Nakata H.; Maeda K.; Ogata H.; Bilcer G.; Devasamudram T.; Kincaid J. F.; Boross P.; Wang Y.-F.; Tie Y.; Volarath P.; Gaddis L.; Harrison R. W.; Weber I. T.; Ghosh A. K.; Mitsuya H. A Novel bis-Tetrahydrofuranylurethane-containing Non-peptide Protease Inhibitor (PI) UIC-94017 (TMC114) Potent Against Multi-PI-Resistant HIV In Vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003, 47, 3123–3129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura K.; Kato R.; Kavlick M. F.; Nguyen A.; Maroun V.; Maeda K.; Hussain K. A.; Ghosh A. K.; Gulnik S. V.; Erickson J. W.; Mitsuya H. UIC-94003: A Potent Protease Inhibitor (PI) That Inhibits Multi-PI-Resistant HIV-1 Replication in vitro. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 1349–1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tie Y.; Boross P. I.; Wang Y. F.; Gaddis L.; Hussain A. K.; Leshchenko S.; Ghosh A. K.; Louis J. M.; Harrison R. W.; Weber I. T. High Resolution Crystal Structures of HIV-1 Protease with a Potent Non-Peptide Inhibitor (UIC-94017) Active Against Multi-Drug-Resistant Clinical Strains. J. Mol. Biol. 2004, 338, 341–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. F.; Tie Y.; Boross P. I.; Tozser J.; Ghosh A. K.; Harrison R. W.; Weber I. T. Potent new antiviral compound shows similar inhibition and structural interactions with drug resistant mutants and wild type HIV-1 protease. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 4509–4515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kear J. L.; Blackburn M. E.; Veloro A. M.; Dunn B. M.; Fanucci G. E. Subtype polymorphisms among HIV-1 protease variants confer altered flap conformations and flexibility. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 14650–14651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coman R. M.; Robbins A. H.; Goodenow M. M.; Dunn B. M.; McKenna R. High-resolution structure of unbound human immunodeficiency virus 1 subtype C protease: implications of flap dynamics and drug resistance. Acta Crystallogr., D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2008, D64, 754–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F.; Kovalevsky A. Y.; Louis J. M.; Boross P. I.; Wang Y. F.; Harrison R. W.; Weber I. T. Mechanism of drug resistance revealed by the crystal structure of the unliganded HIV-1 protease with F53L mutation. J. Mol. Biol. 2006, 358, 1191–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.