Abstract

Background: Little is known about the association between eating patterns and type 2 diabetes (T2D) risk.

Objective: The objective of this study was to prospectively examine associations between breakfast omission, eating frequency, snacking, and T2D risk in men.

Design: Eating patterns were assessed in 1992 in a cohort of 29,206 US men in the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study who were free of T2D, cardiovascular disease, and cancer and were followed for 16 y. We used Cox proportional hazards analysis to evaluate associations with incident T2D.

Results: We documented 1944 T2D cases during follow-up. After adjustment for known risk factors for T2D, including BMI, men who skipped breakfast had 21% higher risk of T2D than did men who consumed breakfast (RR: 1.21; 95% CI: 1.07, 1.35). Compared with men who ate 3 times/d, men who ate 1–2 times/d had a higher risk of T2D (RR: 1.25; 95% CI: 1.08, 1.45). These findings persisted after stratification by BMI or diet quality. Additional snacks beyond the 3 main meals (breakfast, lunch, and dinner) were associated with increased T2D risk, but these associations were attenuated after adjustment for BMI.

Conclusions: Breakfast omission was associated with an increased risk of T2D in men even after adjustment for BMI. A direct association between snacking between meals and T2D risk was mediated by BMI.

INTRODUCTION

Type 2 diabetes (T2D)5 prevalence is escalating with a major impact on morbidity and premature mortality worldwide (1). The prevalence of skipping breakfast has progressively increased over the past decades in children, adolescents (2), and adults (3). There is increasing evidence that skipping breakfast is associated with excess weight gain and other adverse health outcomes (4). In addition, eating frequency or snacking may also impact body weight and risk of metabolic diseases (4, 5). However, most previous studies on breakfast frequency and quality in the etiology of obesity and chronic diseases were small, and the results are inconsistent (4, 5).

Therefore, we prospectively examined in the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study whether breakfast consumption, eating frequency, and snacking were associated with T2D risk and whether these associations were mediated through BMI (in kg/m2). We also examined potential modification of associations by BMI, dietary patterns, dietary glycemic index, glycemic load, and cereal fiber.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Study population

The Health Professionals Follow-Up Study is an ongoing prospective study of 51,529 male health professionals, including dentists, veterinarians, pharmacists, optometrists, osteopaths, and podiatrists, who were aged 40–75 y on enrollment in 1986. Participants have been followed through mailed biennial questionnaires about their medical histories, lifestyles, and health-related behaviors. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Harvard School of Public Health (Boston, MA).

Dietary assessment

Diet over the previous year was first assessed in 1986 by using a 131-item food-frequency questionnaire (FFQ). Dietary information was updated with subsequent similar FFQs mailed every 4 y thereafter (1990, 1994, 1998, 2002, and 2006). Follow-up was complete for >90% in each 2-y cycle. Nine mutually exclusive response categories were provided for the frequency of intake. Nutrient intakes were calculated by converting the frequency responses to daily intakes for each food or beverage, multiplying the daily intakes of each food and beverage with its corresponding nutrient content, and summing the contributions of all items. The validity and reproducibility of the FFQ have been reported elsewhere (6, 7). In brief, the deattenuated correlation coefficient between FFQ and diet records ranged from 0.32 for energy-adjusted protein to 0.63 for energy-adjusted saturated fat to 0.81 for energy-adjusted vitamin B-6.

In 1992, the questionnaire included the item “Please indicate the times of day that you usually eat.” Participants could indicate all of the predefined categories that applied (ie, before breakfast, breakfast, between breakfast and lunch, lunch, between lunch and dinner, dinner, between dinner and bedtime, and after going to bed). In this study, breakfast, lunch, and dinner were considered meals, whereas eating at other occasions was considered snacking. Hence, participants could report eating between 1 and 8 times/d. Because the question focused on eating, it is most likely that the drinking of coffee, tea, soft drinks, or other beverages was not considered a snack in the study. However, coffee intake was accounted for in our multivariable models.

Dietary patterns were identified from FFQs as previously described in detail (6). Principal components analysis was used to generate factors that were linear combinations of consumed foods. Based on these factors, Western and prudent dietary pattern scores were calculated. The prudent dietary pattern is characterized by increased consumption of fruit, vegetables, fish, poultry, and whole grains, whereas the Western dietary pattern is characterized by an increased consumption of red meat, processed meat, French fries, high-fat dairy products, refined grains, and sweets and desserts. These patterns were previously associated with T2D risk (8) and were used in the current analysis to reflect the overall diet quality.

The glycemic index is a measure of the postprandial blood glucose response per gram of carbohydrate of a food compared with a reference food such as white bread or glucose. The dietary glycemic load was calculated by multiplying the carbohydrate content of each food by its glycemic index, multiplying this value by the frequency of consumption, and summing these values for all foods. Hence, the glycemic load represents both the quality and quantity of the carbohydrate consumed. Participants were asked to report their average intake of coffee with caffeine (in cups) and decaffeinated coffee (in cups) over the preceding year. Alcohol consumption and cereal fiber intake were assessed as described previously (9, 10).

Measurement of nondietary factors

Family history of T2D was assessed in 1990. Lifestyle factors such as physical activity, BMI, cigarette smoking, and medical conditions were assessed biannually. Physical activity was expressed as hours per week and converted to metabolic equivalent task hours (MET-h)/wk by using a validated questionnaire (11). BMI was calculated as weight (in kg) divided by the square of height (in m).

Exclusion of participants at baseline

Because eating frequency was first assessed in 1992, we used 1992 as the baseline for the current analysis. Participants who did not complete the original 1986 FFQ, had implausible energy intakes (>4200 or <800 kcal/d), had left >70 food items blank, or did not answer the meal-frequency questions in 1992 were excluded from the study. We also excluded participants with a diagnosis of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer (except for nonmelanoma skin cancer) between 1986 and 1992. Thus, 29,206 men remained for follow-up from 1992 to 2008.

Case ascertainment

On each biennial questionnaire, participants were asked whether they had been diagnosed during the previous 2 y with T2D. Men who reported a diagnosis of T2D on the biennial questionnaire were sent a supplementary questionnaire on symptoms, treatment, and laboratory glucose concentrations to confirm the diagnosis. The National Diabetes Data Group criteria were used to confirm a self-reported diagnosis of T2D (12). For T2D cases identified after 1998, the American Diabetes Association criteria were applied (13). Between 1992 and 2008, 1944 diabetes cases were diagnosed in eligible men. In a validation study of the supplementary questionnaire for diabetes diagnosis, a medical record review confirmed 97% (57 of 59) of self-reported T2D cases (14).

Statistical analysis

Participants contributed follow-up time from the date they returned their baseline questionnaire (1992) to the date of diagnosis of T2D, death, or the end of the study period (31 January 2008), whichever came first. To examine associations between the breakfast-consumption pattern and T2D risk, we estimated RRs and 95% CIs by using the Cox proportional hazards regression model (after checking that the proportional hazards assumption held) with age in months at baseline and calendar year as stratification variables. We analyzed breakfast consumption as a binary variable (yes or no) in conjunction with “the number of eating occasions” (1–3 and 4–7 times/d) in relation to T2D risk. We also analyzed eating frequency (meals and snacks), eating occasions and snacks in addition to the 3 main meals (breakfast, lunch, and dinner), and evening snacks (eating after dinner time or before going to bed or both) in relation to T2D risk.

In the basic multivariate models, in addition to stratification by age and time period, we adjusted for known and suspected risk factors of T2D including family history of T2D (yes or no), BMI (<23, 23–24.9, 25–29.9, ≥30, or missing), energy intake (kcal/d, continuous), alcohol intake (0 to <5, 5 to <15, or ≥15 g/d), cereal fiber intake (g/d, quintiles), physical activity (1 to <3, 3 to <9, 9 to <18, 18 to <27, and ≥27 MET-h/wk or missing), smoking status (never, past, or currently 1–14, 15–24, or ≥25 cigarettes/d), prudent dietary pattern (quintiles), and Western dietary pattern (quintiles). We ran these models with and without BMI adjustment (which was updated by using the information collected every 2 y) to assess whether the association between eating patterns and T2D was mediated by BMI. In additional multivariate models, we further adjusted for total coffee consumption (caffeinated and decaffeinated; 0 to <2 or ≥ 2 cups/d), and glycemic load (continuous). In models in which eating frequency was not the main exposure, we also adjusted for the number of meals (1–2, 3, 4, or 5–8 meals). Cumulative averages of physical activity, glycemic index, glycemic load, prudent and Western dietary patterns, and dietary covariates (energy, cereal fiber, and alcohol) were calculated at each time point to better represent the long-term diet and activity and to minimize within-person variation (15). The residual method was used to adjust the glycemic index, glycemic load, and intakes of cereal fiber for total energy intake (16). We stopped updating diet when participants first reported a chronic disease diagnosis (eg, cancer, cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure, and hypercholesterolemia) because subjects with any of these conditions may have changed their diets. All other covariates were updated for each 2-y follow-up period. Tests for trend were calculated by including the median category of eating frequency as an ordinal variable in the model.

We conducted joint analyses and interaction tests for each of the breakfast-consumption pattern (yes or no) and additional eating occasions beyond the 3 main meals (ie, snack consumption: none, 1, or ≥2 snacks/d) in relation to diabetes risk according to quintiles of BMI, prudent dietary pattern, Western dietary pattern, glycemic load, glycemic index, and cereal fiber intake. The likelihood ratio test was used to compare the model including the cross-product terms [eg, breakfast consumption (binary) × medians of deciles of BMI (ordinal)] with a model that included only main effects.

Because some men who reported skipping breakfast also reported eating before breakfast (4%) or before lunch (21%), we assessed, in a sensitivity analysis, T2D risk in men who did not eat anything before lunchtime (13%) compared with men who ate at least once before lunch (87%). Furthermore, because weight loss could have an impact on T2D risk, we performed another sensitivity analysis that excluded participants who lost >10% of their body weight between 1990 and 1992. SAS software (version 9.1; SAS) was used for all analyses, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

In this cohort of 29,206 men, the majority of subjects (83%) consumed breakfast. Compared with breakfast consumers, men who skipped breakfast had a slightly higher BMI, smoked more, exercised less, consumed more alcohol and less cereal fiber, and drank more coffee. Also, men who skipped breakfast tended to have poorer diet quality reflected by a lower prudent dietary pattern score and a higher Western dietary pattern score than did breakfast consumers (all P < 0.05) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Age-standardized baseline participant characteristics by breakfast consumption in 29,206 US men from the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study1

| Breakfast consumers | Breakfast nonconsumers | |

| n | 24,173 | 5033 |

| Age (y) | 58.2 ± 9.22 | 57.8 ± 8.7 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.4 (2.9) | 26.0 (3.0) |

| Family history of diabetes (%) | 13 | 13 |

| Current smoking (%) | 5 | 15 |

| Physical activity (MET-h3/wk) | 38.3 ± 41.7 | 34.4 ± 40.5 |

| Alcohol intake (g/d) | 10.4 ± 13.3 | 13.9 ± 16.8 |

| Energy intake (kcal/d) | 2006 ± 574 | 1910 ± 598 |

| Dietary glycemic load | 128 ± 44 | 112 ± 45 |

| Dietary glycemic index | 53.2 ± 3.2 | 52.2 ± 3.6 |

| Cereal fiber intake (g/d)4 | 6.5 ± 3.7 | 4.4 ± 2.8 |

| Prudent dietary score (percentage above the median)5 | 53 | 33 |

| Western dietary score (percentage above the median)6 | 50 | 55 |

| Coffee intake (includes decaffeinated), servings/d | 1.8 ± 1.6 | 2.3 ± 1.9 |

| Eating occasions (times/d) | 3.0 ± 0.7 | 2.0 ± 0.7 |

| Eat before breakfast (%) | 0 | 4 |

| Eat between breakfast and lunch (brunch) (%) | 7 | 21 |

| Eat lunch (%) | 93 | 77 |

| Eat between lunch and dinner (%) | 12 | 11 |

| Eat dinner (%) | 98 | 93 |

| Eat before going to bed (%) | 43 | 47 |

| Eat after going to bed (%) | 1 | 2 |

| Snacks (%)7 | 51 | 62 |

Compared with breakfast consumers, men who skipped breakfast had a slightly higher BMI, smoked more, exercised less, consumed more alcohol and less cereal fiber, and drank more coffee. Also, men who skipped breakfast tended to have poorer diet quality as reflected by a lower prudent dietary pattern score and a higher Western dietary pattern score than did breakfast consumers (all P < 0.05).

Mean ± SD (all such values).

MET-h, metabolic equivalent task hours.

Nutrient intakes were energy-adjusted.

In general, a higher prudent dietary score indicated better diet quality.

In general, a higher Western dietary score indicated worse diet quality.

Defined as eating at other occasions beyond the 3 main meals (breakfast, lunch, and dinner). On average, 43% of the sample snacked 1 time/d, and 11% of the sample snacked ≥2 times/d.

After adjustment for age, there was a 50% higher risk of T2D in men who skipped breakfast than in men who consumed breakfast (Table 2). This direct association remained significant after adjustment for dietary and other risk factors for T2D (multivariable RR: 1.27; 95% CI: 1.13, 1.43). The association also remained significant after additional adjustment for BMI (21% increased risk), which was a potential mediator.

TABLE 2.

RRs of T2D for 2 categories of breakfast consumption1

| Breakfast consumption |

|||

| Consumers | Nonconsumers | P | |

| T2D cases | 1505 | 439 | — |

| Person-years | 346,179 | 72,725 | — |

| Age | 1.00 (ref)2 | 1.50 (1.34, 1.67) | <0.001 |

| MV model | 1.00 (ref) | 1.27 (1.13, 1.43) | <0.001 |

| MV model + BMI3 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.21 (1.07, 1.35)4 | <0.01 |

MV models were adjusted for age (mo), family history of T2D (yes or no), energy intake (kcal/d, continuous), alcohol intake (g/d, continuous), cereal fiber intake (g/d, quintiles), physical activity (1 to <3, 3 to <9, 9 to <18, 18 to <27, and ≥27 metabolic equivalent task hours/wk), smoking status (never, past, or currently 1–14, 15–24, or ≥25 cigarettes/d), prudent dietary pattern (quintiles), and Western dietary pattern (quintiles). MV, multivariate; ref, reference; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

RR (95% CI) from Cox proportional hazards model (all such values).

Same as the previous MV model in addition to BMI (in kg/m2) (<23, 23–24.9, 25–29.9, and ≥30).

In a first sensitivity analysis, when we compared men who did not eat anything before lunchtime with men who ate at least once before lunchtime, results were very similar to the breakfast-T2D association shown in Table 2 [MV RR (95% CI) after adjustment for BMI: 1.23; 1.08, 1.39].

Compared with men who ate 3 times/d, the relation between increased eating frequency and T2D risk was direct for men who ate 4 times/d and nonsignificant for men who ate 5–8 times/d before adjustment for BMI (Table 3). These associations appeared to be mediated by an increased BMI because they became nonsignificant after additional adjustment for BMI, even though the P-trend was significant (P-trend = 0.04). The association was further weakened, and the P-trend became nonsignificant after other covariates in the model, such as breakfast consumption (P-trend = 0.36), coffee intake (P-trend = 0.39), and glycemic load (P-trend = 0.39), were controlled for. Men who ate 1–2 times/d also had a higher risk of T2D than did men consumed 3 meals/d (multivariable RR: 1.26; 95% CI: 1.09, 1.46). This association appeared to not be mediated by BMI because it was not materially altered after additional adjustment for BMI. Furthermore, when we classified participants according to their breakfast consumption combined with their eating frequency, the results were similar to their independent effects; men who skipped breakfast and ate 1–3 times/d were at a higher T2D risk than were men who consumed breakfast and ate 1–3 times/d (Table 4). For the same comparison, men who ate 4–7 times/d with or without breakfast were also at a higher T2D risk; however, this higher risk became attenuated or nonsignificant after additional adjustment for BMI. Furthermore, an increasing number of eating occasions in addition to 3 standard meals (breakfast, lunch, and dinner) was associated with an increased T2D risk (Table 5). This association was also mediated by BMI. Similar direct associations mediated by BMI were shown when we compared men who snacked after dinner time or before they went to bed or both with men who refrained from eating after dinner time (Table 6). In all of the mentioned analyses, although the influence of dietary adjustment was relatively minor, BMI was mostly responsible for the attenuation in estimates.

TABLE 3.

RRs of T2D for 4 categories of eating (meals and snacks) frequency1

| Eating frequency |

|||||

| 1–2 times/d | 3 times/d | 4 times/d | 5–8 times/d | P-trend | |

| T2D cases | 254 | 835 | 714 | 141 | — |

| Person-years | 46,387 | 200,695 | 139,893 | 31,929 | — |

| Age | 1.39 (1.20, 1.60)2 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.25 (1.13, 1.38) | 1.10 (0.92, 1.31) | 0.72 |

| MV model | 1.26 (1.09, 1.46) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.19 (1.07, 1.32) | 1.01 (0.84, 1.22) | 0.53 |

| MV model + BMI3 | 1.25 (1.08, 1.45) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.09 (0.99, 1.21) | 0.90 (0.75, 1.09) | 0.04 |

MV models were adjusted for age (mo), family history of T2D (yes or no), energy intake (kcal/d, continuous), alcohol intake (g/d, continuous), cereal fiber intake (g/d, quintiles), physical activity (1 to <3, 3 to <9, 9 to <18, 18 to <27, and ≥27 metabolic equivalent task hours/wk), smoking status (never, past, or currently 1–14, 15–24, or ≥25 cigarettes/d), prudent dietary pattern (quintiles), and Western dietary pattern (quintiles). MV, multivariate; ref, reference; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

RR (95% CI) from Cox proportional hazards model (all such values).

Same as the previous MV model in addition to BMI (in kg/m2) (<23, 23–24.9, 25–29.9, and ≥30).

TABLE 4.

RRs of T2D for 4 categories of breakfast and eating frequency1

| Breakfast and eating frequency |

||||

| No breakfast + 1–3 times/d | No breakfast + 4–7 times/d | Breakfast + 1–3 times/d | Breakfast + 4–7 times/d | |

| T2D cases | 392 | 47 | 697 | 808 |

| Person-years | 66,379 | 6,345 | 180,702 | 165,476 |

| Age | 1.68 (1.48, 1.91)2 | 2.20 (1.63, 2.97) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.31 (1.18, 1.45) |

| MV model | 1.37 (1.20, 1.57) | 1.67 (1.23, 2.26) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.20 (1.08, 1.33) |

| MV model + BMI3 | 1.24 (1.08, 1.42) | 1.37 (1.01, 1.86) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.07 (0.96, 1.19) |

MV models were adjusted for age (mo), family history of T2D (yes or no), energy intake (kcal/d, continuous), alcohol intake (g/d, continuous), cereal fiber intake (g/d, quintiles), physical activity (1 to <3, 3 to <9, 9 to <18, 18 to <27, and ≥27 metabolic equivalent task hours/wk), smoking status (never, past, or currently 1–14, 15–24, or ≥25 cigarettes/d), prudent dietary pattern (quintiles), and Western dietary pattern (quintiles). MV, multivariate; ref, reference; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

RR (95% CI) from Cox proportional hazards model (all such values).

Same as the previous MV model in addition to BMI (in kg/m2) (<23, 23–24.9, 25–29.9, and ≥30).

TABLE 5.

RRs of T2D for number of eating occasions added to the 3 regular meals per day1

| Eating frequency |

||||

| Breakfast, lunch, and dinner | Plus 1 snack/d | Plus ≥2 snacks/d | P-trend | |

| T2D cases | 590 | 665 | 129 | — |

| Person-years | 158,004 | 132,365 | 29,927 | — |

| Age | 1.00 (ref)2 | 1.40 (1.25, 1.57) | 1.21 (1.00, 1.47) | <0.001 |

| MV model | 1.00 (ref) | 1.29 (1.14, 1.44) | 1.10 (0.90, 1.34) | 0.05 |

| MV model + BMI3 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.13 (1.01, 1.28) | 0.95 (0.77, 1.16) | 0.99 |

MV models were adjusted for age (mo), family history of T2D (yes or no), energy intake (kcal/d, continuous), alcohol intake (g/d, continuous), cereal fiber intake (g/d, quintiles), physical activity (1 to <3, 3 to <9, 9 to <18, 18 to <27, and ≥27 metabolic equivalent task hours/wk), smoking status (never, past, or currently 1–14, 15–24, or ≥25 cigarettes/d), prudent dietary pattern (quintiles), and Western dietary pattern (quintiles). MV, multivariate; ref, reference; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

RR (95% CI) from Cox proportional hazards model (all such values).

Same as the previous MV model in addition to BMI (in kg/m2) (<23, 23–24.9, 25–29.9, and ≥30).

TABLE 6.

RRs of T2D for 2 categories of evening snacks1

| Not eat after dinner time | Eat after dinner time | P value | |

| T2D cases | 947 | 997 | — |

| Person-years | 230,833 | 188,070 | — |

| Age | 1.00 (ref)2 | 1.34 (1.22, 1.46) | <0.001 |

| MV model | 1.00 (ref) | 1.18 (1.08, 1.30) | <0.001 |

| MV model + BMI3 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.05 (0.96, 1.16) | 0.29 |

Evening snacks are defined as eating after dinner time or before going to bed or both. MV models were adjusted for age (mo), family history of T2D (yes or no), energy intake (kcal/d, continuous), alcohol intake (g/d, continuous), cereal fiber intake (g/d, quintiles), physical activity (1 to <3, 3 to <9, 9 to <18, 18 to <27, and ≥27 metabolic equivalent task hours/wk), smoking status (never, past, or currently 1–14, 15–24, or ≥25 cigarettes/d), prudent dietary pattern (quintiles), and Western dietary pattern (quintiles). MV, multivariate; ref, reference; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

RR (95% CI) from Cox proportional hazards model (all such values).

Same as the previous MV model in addition to BMI (in kg/m2) (<23, 23–24.9, 25–29.9, and ≥30).

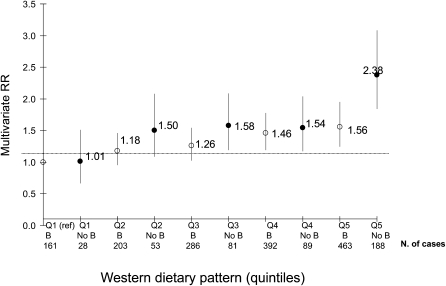

We also examined interactions with BMI, and there was no evidence of any effect modification of breakfast-consumption pattern (P-interaction = 0.34) and snack consumption beyond the 3 main meals (P-interaction = 0.67). The prudent dietary pattern, glycemic load, glycemic index, or cereal fiber intake did not modify the association between breakfast consumption and T2D (all P-interaction ≥ 0.26) or the association between snack consumption beyond the 3 main meals and T2D (all P-interaction ≥ 0.22). The only significant interaction was between breakfast consumption and the Western dietary pattern in relation to T2D risk (P-interaction = 0.03), of which stronger effects were seen for the combination of skipping breakfast and having a Western dietary pattern than for these factors separately (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Breakfast consumption and Western dietary pattern in relation to T2D risk. Filled circles represent the RR for No B, and the open circles represent the RR for B. Values are RRs from Cox proportional hazards models (P-interaction = 0.03). All multivariate models were adjusted for age (mo), family history of T2D (yes or no), energy intake (kcal/d, continuous), alcohol intake (g/d, continuous), cereal fiber intake (g/d, Qs), physical activity (1 to <3, 3 to <9, 9 to <18, 18 to <27, and ≥27 metabolic equivalent task hours/wk), smoking status (never, past, or currently 1–14, 15–24, or ≥25 cigarettes/d), prudent dietary pattern (Qs), glycemic load (continuous), and eating frequency (1–2, 3, 4, or 5–8 meals/d). B, breakfast consumers; No B, breakfast skippers; Q, quintile; ref, reference; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

When we compared men who did not eat anything before lunchtime with men who ate at least once before lunchtime in a first sensitivity analysis, results were very similar to the breakfast-T2D association shown in Table 2 (multivariable RR after adjustment for BMI: 1.23; 95% CI: 1.08, 1.39). When we excluded men who lost >10% of their baseline body weight between 1990 and 1992 (n = 2906) in a second sensitivity analysis, overall results did not materially change (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In this large prospective study, breakfast consumption was inversely associated with T2D risk in men. Eating frequency and snack consumption were both directly associated with T2D risk and mediated by BMI, which indicated that the adverse effect of increased eating frequency or snacks on T2D risk was partially mediated through its effect on body weight. Eating frequency only 1 or 2 times/d was also associated with an increased T2D risk compared with eating 3 meals/d. Furthermore, having 3 main meals per day, including breakfast, seemed to be the optimal eating pattern for a decreased T2D risk compared with any other combination of eating occasions and breakfast consumption. Neither BMI nor diet quality, as reflected by the prudent dietary pattern, glycemic load, glycemic index, or cereal fiber intake, modified the associations between eating patterns and T2D risk, with the only exception of Western dietary pattern that significantly interacted with the breakfast-consumption pattern.

Breakfast consumption and T2D risk

Data on breakfast frequency and quality in relation to the development of adult obesity and chronic diseases are limited and inconsistent (4). In several observational studies, skipping breakfast was associated with increased BMI (17, 18) and increased mortality (19). However, randomized controlled trials that assessed breakfast habits in relation to changes in body weight provided mixed results and were few, small, and short term (20–22). Both breakfast consumption and its healthy composition have been shown to control appetite and blood glucose concentrations in children and adults (23). An earlier prospective analysis in our cohort showed an inverse association between breakfast consumption and weight gain during 10 y of follow-up. Conversely, an increased eating frequency was associated with an increased weight gain (24). These 2 findings could partly explain our results on why breakfast consumption, but no other eating occasions or snacks, was associated with a lower T2D risk.

According to a randomized crossover trial in 44 T2D adult patients, a low–glycemic load breakfast improved postprandial glycemic, insulinemic, and free fatty acid responses compared with a high–glycemic load breakfast (25). However, another 6-mo randomized trial in T2D subjects showed no significant difference in the reduction in glycemic effect of the consumption of high– compared with low–glycemic index breakfast (26). Also, the consumption of both whole-grain and refined-grain breakfast cereal was associated with decreased weight gain in the Physicians Health Study (27). Similarly, in the current study, the prudent dietary pattern, glycemic load, or cereal fiber intake did not modify the breakfast consumption-T2D inverse association. These results suggested that breakfast consumption itself has independent metabolic effects over and above the role of dietary quality. Nevertheless, our results suggested that the combination of poor diet quality (Western pattern) with a poor meal pattern (skipping breakfast) is particularly detrimental.

Eating frequency and T2D risk

Increased meal frequency while keeping energy intake constant has been suggested to improve risk factors for chronic diseases in patients with T2D (4). Similar metabolic advantages have also been shown in normal individuals through a reduction in serum insulin and lipid concentrations (28). Conversely, a reduced meal frequency or intermittent fasting in mice, independent of caloric intake (29, 30), has been shown to reduce blood glucose and insulin concentrations and improve glucose tolerance. The same improved glycemic response has been observed under calorie restriction in obese patients with T2D (∼400–1000 kcal/d) (31) and in rats (29, 30). Potential cellular mechanisms involve suppression of oxidative stress through a reduction of the amount of superoxide anion radical produced in the mitochondria as a result of dietary restriction (32). An early review concluded that a decreased meal frequency was beneficial for the nervous and cardiovascular systems and most other organs in animals as a result of a stimulation of protein production that enhances resistance to oxidative and metabolic stress (33). Earlier trials showed no impact on glucose metabolism in T2D subjects when 3- and 9-meal regimens for 4 wk were compared (34) or 3- and 8-meal regimens for 2 wk were compared (35). However, our results showed an increased T2D risk associated with a decreased eating frequency (1–2 times/d), possibly because men who ate 1–2 times/d were mostly the same men who skipped breakfast (75%) or they could have been underreporting their eating frequency because beverages, especially sugar-sweetened beverages, could have been part of their diet without being considered an additional eating occasion.

In addition, an increased eating frequency beyond the main 3 meals was associated with increased T2D risk. One possible reason for the increased risk is that, as opposed to the experimental trials that held total energy intake constant while increasing eating frequency (28), the increased meal frequency may have led to an increased energy intake in our cohort of free-living men because BMI was a mediator of these associations with an increased risk of T2D.

Snack consumption and T2D risk

Snack consumption, especially if the snack is eaten in a nonhungry state, may be associated with excess weight gain, mostly because of the snack high-energy content, palatability, and high amounts of refined carbohydrates and sugar that may result in low satiety and increased hunger (34). Even though high-protein snacks induced a higher satiety than high-carbohydrate or high-fat ones, the subsequent total energy intake during the next meal was still higher in all snack conditions than in no snack conditions in an earlier experiment in which each subject served as his own control (36). This result was concordant with our results that showed a significant association between snack consumption and risk of T2D, which was explained by BMI, and suggested that BMI mediated the association with T2D risk. Conversely, an earlier review on the same topic concluded that snacking may have positive advantages in terms of weight control compared with the consumption of 3 meals/d because of increased diet-induced thermogenesis and decreased efficient energy use (37). Potential reasons for the discrepant results between the old (37) and recent (34) reviews are the progressive increase in portion sizes and the decrease in snack quality over the years that led to increased energy density (defined as the energy content per gram of food eaten) (38) and increased energy intake (39). The potential underreporting (40) of energy-dense snack foods (41), especially by obese people, could be another reason.

Other potential mechanisms

Breakfast consumption has been shown to improve lipid metabolism by reducing fasting and total LDL cholesterol (22, 42) and the serum triglyceride concentration (43). As long as breakfast does not lead to a significant increase in energy intake, it may reduce risk of lipid-associated chronic diseases such as obesity, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes mellitus because of favorable changes in glycemia and insulenemia (5). Infrequent large meals have been associated with increased serum insulin, free fatty acid concentrations, and de novo lipogenesis (44).

Also, breakfast is a unique meal because it is the time when prolonged fasting ceases. In fact, the longer the fasting time is, the higher the ghrelin concentrations are (45) and the lower the insulin concentrations are (46), which could induce hunger and eating. Breakfast consumption, especially if it consisted of fiber-rich foods rather than refined cereals, could lead to an improved postprandial glycemic response and insulin sensitivity (25, 47–50). Between-meal hypoglycemia would then be reduced (25, 47, 50) as well as appetite (4). Food intake in the morning was shown to be particularly satiating and associated with less appetite and weight control (51). Notably, weight control could be a mechanism by which breakfast consumption could lower T2D risk; nevertheless, the modest attenuation of the effect estimate after adjustment for BMI suggested that the observed association was not completely mediated via weight control.

Limitations and strengths

There were several limitations to the current study. First, nondifferential measurement error in our assessment of breakfast consumption and eating frequency may have biased our results toward the null (52). Breakfast consumption was self-reported and subject to a subjective interpretation of what constitutes a breakfast. Nevertheless, when we compared breakfast consumers to before-noon eaters, our results did not change. Also, meal patterns may have changed over time, and repeated assessment of the meal-frequency question over a 12-y period would have reduced the random within-person measurement error (53). Second, there was no information of the nutrient composition of the breakfast consumed, and beverages consumed without food were likely not included in the eating-frequency assessment. However, the dietary pattern, glycemic index, glycemic load, and cereal fiber intake were used to assess whether the results for eating pattern reflected the overall dietary quality. Third, the question on the eating pattern has not been validated and was asked in such a way that there was no possible way to know how many times participants ate between meals or before or after meals. Finally, it is well known that total energy intake is substantially underreported by the FFQ, and thus, our adjustment for energy intake was likely to be incomplete. Because we did not have energy intake measured by doubly labeled water, we were able to correct measurement errors for self-reported total energy intake.

Despite these limitations, there were several strengths to our study. First, the study included a large sample of men who were followed for 14 y. Second, to our knowledge, this was the first large, prospective design to assess the relation between breakfast consumption and T2D risk because most studies have assessed obesity, morbidity, or mortality outcomes. Third, combinations of eating patterns were tested (eg, breakfast skipping and eating occasions), and the modification of the association for breakfast skipping by other dietary variables such as dietary pattern and glycemic load was assessed. Fourth, eating frequency was assessed independently of other dietary variables, and information on a wide variety of potential confounding variables was repeatedly collected during follow-up, which allowed for more complete control of known potential confounders.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that breakfast consumption may decrease T2D risk in men, which is an association that was not explained by indicators of dietary quality or by BMI. Both decreased eating frequency (1–2 times/d) and increased eating frequency (≥4 times/d) or snack consumption were associated with increased T2D risk, but these associations appeared to be mediated by higher BMI. Additional studies are needed to elucidate this association in women and in other ethnic and racial groups and to conduct an in-depth analysis of specific breakfast foods.

Acknowledgments

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—RAM and FBH: collected data and had the idea for the current analysis; RAM: analyzed data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript; and all authors: provided statistical expertise, contributed to the interpretation of the results and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approved the final version of the manuscript. None of the authors had a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: FFQ, food-frequency questionnaire; MET-h, metabolic equivalent task hours; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hogan P, Dall T, Nikolov P. Economic costs of diabetes in the US in 2002. Diabetes Care 2003;26:917–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siega-Riz AM, Popkin BM, Carson T. Trends in breakfast consumption for children in the United States from 1965-1991. Am J Clin Nutr 1998;67:748S–56S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haines PS, Guilkey DK, Popkin BM. Trends in breakfast consumption of US adults between 1965 and 1991. J Am Diet Assoc 1996;96:464–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Timlin MT, Pereira MA. Breakfast frequency and quality in the etiology of adult obesity and chronic diseases. Nutr Rev 2007;65:268–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCrory MA, Campbell WW. Effects of eating frequency, snacking, and breakfast skipping on energy regulation: symposium overview. J Nutr 2011;141:144–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Litin LB, Willett WC. Reproducibility and validity of an expanded self-administered semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire among male health professionals. Am J Epidemiol 1992;135:1114–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feskanich D, Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Litin LB, Willett WC. Reproducibility and validity of food intake measurements from a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. J Am Diet Assoc 1993;93:790–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Dam RM, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, Hu FB. Dietary patterns and risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus in U.S. men. Ann Intern Med 2002;136:201–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joosten MM, Chiuve SE, Mukamal KJ, Hu FB, Hendriks HF, Rimm EB. Changes in alcohol consumption and subsequent risk of type 2 diabetes in men. Diabetes 2011;60:74–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Munter JS, Hu FB, Spiegelman D, Franz M, van Dam RM. Whole grain, bran, and germ intake and risk of type 2 diabetes: a prospective cohort study and systematic review. PLoS Med 2007;4:e261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chasan-Taber S, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Spiegelman D, Colditz GA, Giovannucci E, Ascherio A, Willett WC. Reproducibility and validity of a self-administered physical activity questionnaire for male health professionals. Epidemiology 1996;7:81–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williamson DA, Rejeski J, Lang W, Van Dorsten B, Fabricatore AN, Toledo K. Impact of a weight management program on health-related quality of life in overweight adults with type 2 diabetes. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:163–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hagberg LA, Lindholm L. Cost-effectiveness of healthcare-based interventions aimed at improving physical activity. Scand J Public Health 2006;34:641–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabin R, de Charro F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med 2001;33:337–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Willett WC. Nutritional epidemiology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Willett WC, Howe GR, Kushi LH. Adjustment for total energy intake in epidemiologic studies. Am J Clin Nutr 1997;65(suppl):1220S–8S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song WO, Chun OK, Obayashi S, Cho S, Chung CE. Is consumption of breakfast associated with body mass index in US adults? J Am Diet Assoc 2005;105:1373–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma Y, Bertone ER, Stanek EJ, 3rd, Reed GW, Hebert JR, Cohen NL, Merriam PA, Ockene IS. Association between eating patterns and obesity in a free-living US adult population. Am J Epidemiol 2003;158:85–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaplan GA, Seeman TE, Cohen RD, Knudsen LP, Guralnik J. Mortality among the elderly in the Alameda County Study: behavioral and demographic risk factors. Am J Public Health 1987;77:307–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schlundt DG, Hill JO, Sbrocco T, Pope-Cordle J, Sharp T. The role of breakfast in the treatment of obesity: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Clin Nutr 1992;55:645–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kleemola P, Puska P, Vartiainen E, Roos E, Luoto R, Ehnholm C. The effect of breakfast cereal on diet and serum cholesterol: a randomized trial in North Karelia, Finland. Eur J Clin Nutr 1999;53:716–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farshchi HR, Taylor MA, Macdonald IA. Deleterious effects of omitting breakfast on insulin sensitivity and fasting lipid profiles in healthy lean women. Am J Clin Nutr 2005;81:388–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pereira MA, Erickson E, McKee P, Schrankler K, Raatz SK, Lytle LA, Pellegrini AD. Breakfast frequency and quality may affect glycemia and appetite in adults and children. J Nutr 2011;141:163–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Heijden AA, Hu FB, Rimm EB, van Dam RM. A prospective study of breakfast consumption and weight gain among U.S. men. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:2463–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clark CA, Gardiner J, McBurney MI, Anderson S, Weatherspoon LJ, Henry DN, Hord NG. Effects of breakfast meal composition on second meal metabolic responses in adults with Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Eur J Clin Nutr 2006;60:1122–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsihlias EB, Gibbs AL, McBurney MI, Wolever TM. Comparison of high- and low-glycemic-index breakfast cereals with monounsaturated fat in the long-term dietary management of type 2 diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr 2000;72:439–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bazzano LA, Song Y, Bubes V, Good CK, Manson JE, Liu S. Dietary intake of whole and refined grain breakfast cereals and weight gain in men. Obes Res 2005;13:1952–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jenkins DJ, Wolever TM, Vuksan V, Jenkins DJ, Wolever TM, Vuksan V, Brighenti F, Cunnane SC, Rao AV, Jenkins AL, et al. Nibbling versus gorging: metabolic advantages of increased meal frequency. N Engl J Med 1989;321:929–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anson RM, Guo Z, de Cabo R, Iyun T, Rios M, Hagepanos A, Ingram DK, Lane MA, Mattson MP. Intermittent fasting dissociates beneficial effects of dietary restriction on glucose metabolism and neuronal resistance to injury from calorie intake. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003;100:6216–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang ZQ, Bell-Farrow AD, Sonntag W, Cefalu WT. Effect of age and caloric restriction on insulin receptor binding and glucose transporter levels in aging rats. Exp Gerontol 1997;32:671–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wing RR, Blair EH, Bononi P, Marcus MD, Watanabe R, Bergman RN. Caloric restriction per se is a significant factor in improvements in glycemic control and insulin sensitivity during weight loss in obese NIDDM patients. Diabetes Care 1994;17:30–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guo Z, Ersoz A, Butterfield DA, Mattson MP. Beneficial effects of dietary restriction on cerebral cortical synaptic terminals: preservation of glucose and glutamate transport and mitochondrial function after exposure to amyloid beta-peptide, iron, and 3-nitropropionic acid. J Neurochem 2000;75:314–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mattson MP, Duan W, Guo Z. Meal size and frequency affect neuronal plasticity and vulnerability to disease: cellular and molecular mechanisms. J Neurochem 2003;84:417–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arnold L, Mann JI, Ball MJ. Metabolic effects of alterations in meal frequency in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 1997;20:1651–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomsen C, Christiansen C, Rasmussen OW, Hermansen K. Comparison of the effects of two weeks’ intervention with different meal frequencies on glucose metabolism, insulin sensitivity and lipid levels in non-insulin-dependent diabetic patients. Ann Nutr Metab 1997;41:173–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marmonier C, Chapelot D, Louis-Sylvestre J. Effects of macronutrient content and energy density of snacks consumed in a satiety state on the onset of the next meal. Appetite 2000;34:161–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Drummond S, Crombie N, Kirk T. A critique of the effects of snacking on body weight status. Eur J Clin Nutr 1996;50:779–83 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Piernas C, Popkin BM. Snacking increased among U.S. adults between 1977 and 2006. J Nutr 2010;140:325–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rolls BJ, Roe LS, Meengs JS. Reductions in portion size and energy density of foods are additive and lead to sustained decreases in energy intake. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;83:11–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schoeller DA. Limitations in the assessment of dietary energy intake by self-report. Metabolism 1995;44:18–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heitmann BL, Lissner L, Osler M. Do we eat less fat, or just report so? Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2000;24:435–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith KJ, Gall SL, McNaughton SA, Blizzard L, Dwyer T, Venn AJ. Skipping breakfast: longitudinal associations with cardiometabolic risk factors in the Childhood Determinants of Adult Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2010;92:1316–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamamoto R, Kawamura T, Wakai K, Chihara Y, Anno T, Mizuno Y, Yokoi M, Ohta T, Iguchi A, Ohno Y. Favorable life-style modification and attenuation of cardiovascular risk factors. Jpn Circ J 1999;63:184–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bray GA. Lipogenesis in human adipose tissue: some effects of nibbling and gorging. J Clin Invest 1972;51:537–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cummings DE, Purnell JQ, Frayo RS, Schmidova K, Wisse BE, Weigle DS. A preprandial rise in plasma ghrelin levels suggests a role in meal initiation in humans. Diabetes 2001;50:1714–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boyle PJ, Shah SD, Cryer PE. Insulin, glucagon, and catecholamines in prevention of hypoglycemia during fasting. Am J Physiol 1989;256:E651–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liljeberg HG, Akerberg AK, Bjorck IM. Effect of the glycemic index and content of indigestible carbohydrates of cereal-based breakfast meals on glucose tolerance at lunch in healthy subjects. Am J Clin Nutr 1999;69:647–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kochar J, Djousse L, Gaziano JM. Breakfast cereals and risk of type 2 diabetes in the Physicians’ Health Study I. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:3039–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Song YJ, Sawamura M, Ikeda K, Igawa S, Yamori Y. Soluble dietary fibre improves insulin sensitivity by increasing muscle GLUT-4 content in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2000;27:41–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nestler JE, Barlascini CO, Clore JN, Blackard WG. Absorption characteristic of breakfast determines insulin sensitivity and carbohydrate tolerance for lunch. Diabetes Care 1988;11:755–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.de Castro JM. The time of day of food intake influences overall intake in humans. J Nutr 2004;134:104–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barron BA. The effects of misclassification on the estimation of relative risk. Biometrics 1977;33:414–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Willett WC. Nutritional epidemiology. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1998 [Google Scholar]