Abstract

This study examines the development of the registered dental hygienist in alternative practice in California through an analysis of archival documents, stakeholder interviews, and two surveys of the registered dental hygienist in alternative practice. Designing, testing and implementing a new practice model for dental hygienists took 23 years. Today, registered dental hygienists in alternative practice have developed viable alternative methods for delivering preventive oral health care services in a range of settings with patients who often have no other source of access to care.

Oral health is an important component of people’s overall health and well-being.1 Yet a significant percentage of the population does not have access to affordable and quality dental care services. In California, it is estimated that nearly one-third of young children 11 years old or younger have never visited a dental provider nor have not visited a dental provider in more than one year.2 Dental insurance is less available than medical insurance, and care is often difficult to get even for the insured, particularly those with public insurance.3 The burden of oral disease is disproportionately born by lower-income and rural populations, racial and ethnic minorities, medically compromised or disabled populations, and, increasingly, young children.4

Lack of access to dental care and oral health disparities are two of the most significant policy issues facing the field of dentistry today. After decades of struggling with these issues, policymakers and the professions are considering workforce redesign as a primary strategy for improving access to care with the hope that workforce innovations may reduce disparities in both utilization and oral health outcomes.5 This strategy is regarded by some as a radical move away from the traditional organization of dental services. Yet, for the past 30 years, ongoing efforts have been underway to reconfigure the dental workforce in California. Future efforts will benefit from lessons learned about what is effective, both politically and in practice, and from knowledge about existing infrastructure and policy.

The dental workforce in the United States is made up primarily of dentists, dental specialists, dental hygienists, and dental assistants. This core array of providers has existed since early in the 20th century, yet, underneath the consistency of these broad categories, lies ever-shifting trends in training, scope of practice, and care delivery settings. Each provider type has evolved over time, and together dental providers have developed practices that span a wide number of arrangements. Each configuration of care can be considered a “practice model” made up of and dependent upon a number of factors including; financing, regulation, population needs and demographics, local economies, public health capacity, educational systems, and patient demands. The solo private practice of dentistry is the dominant, but certainly not the only, practice model for delivering oral health care services. This article describes a new and evolving practice model for delivering preventive dental care, the alternative practice of dental hygiene in California.

Background

A large body of literature exists that tracks the supply, demand, and distribution of the dental workforce over time. For example, the American Dental Association reports on the private practice of dentistry annually and outlines the dimensions of this traditional practice model each year.6 Recent studies in California concerned with workforce shortages and the educational pipeline have examined the dental hygiene and dental assisting workforce.7,8 Finally, literature on new workforce models in dental care is now available, although studies of various pilot projects date back to the 1960s and 1970s.9-11 These workforce studies share a focus on a number of important factors including overall trends, changes in educational requirements and scope of practice, quality of care, and the economics of the labor force. However, very few studies document changes in access to care over time as the result of the implementation of a new model of care delivery.

This paper explores the impact of a new practice model on access to care through an examination of the history, evolution, and current practice of alternative practice dental hygiene in California. The data for this study comes from a number of sources. Archival documents and dental and dental hygiene association literature inform the historical analysis. The evolution over time of this new model is documented in two surveys of the hygiene workforce, conducted in 2005/2006 and in 2009 at the University of California, San Francisco. An understanding of the current and future issues facing practitioners working in this new practice model comes from a qualitative study of RDHAPs and related stakeholders conducted by the authors in 2007. These data represents a comprehensive set of perspectives on the alternative practice hygiene.

EACH PROVIDER TYPE has evolved over time, and together dental providers have developed practices that span a wide number of arrangements.

History of Alternative Practice Hygiene

The movement that led to the current provider classification of the registered dental hygienist in alternative practice (RDHAP) was begun within the Southern California Dental Hygienists’ Association in the late 1970s. At that time, there was much experimentation with the education and scope of practice for dental auxiliary personnel across the country, primarily to expand the capacity and efficiency of the dental office. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the W. K. Kellogg Foundation both invested in “dental nurse” pilot programs in the early 1970s. At this time a new approach, the training expanded auxiliary management (TEAM) model was developed whereby educational institutions taught a team approach to dentistry, including the training and management of dental auxiliaries in extended functions.12

In California, this and a number of other workforce pilot projects were made possible by the 1972 passage of AB1503 (Duffy) that enacted the Health Manpower Pilot Project Act (HMPP) into the Health and Safety Code.13 Now called the Health Workforce Pilot Project (HWPP) program, it allows for demonstration of the effectiveness and safety of new or expanded roles for health care professionals through a formal pilot project involving didactic and clinical training, as well as a period of utilization in the work setting. The results of the pilots can be used to inform the Legislature when deciding on new laws that seek to change professional practice laws and licensure board rules. The HWPP program has been used extensively in California for various health professions, most notably in nursing and dentistry.13

In the first decade of the HMPP (1972-1982), there were 27 dental auxiliary pilots proposed. Twenty-one were completed, three were denied, and three were withdrawn due to lack of funding.13 Almost all of the projects were undertaken by faculty at the state’s dental schools or community colleges. The pilot projects impacted dental auxiliary regulation. For example, in 1976 the Board of Dental Examiners (BDE) adopted regulations allowing auxiliaries trained in the pilot programs to practice extended functions (advanced procedures not formerly in their scope of practice). In 1981, the accreditation laws were changed to allow for educational preparation of expanded-duty dental assistants (EDDAs), and by 1984, a number of educational programs for teaching expanded duties to dental assistants and hygienists were in place.13

In 1981, a group of dental hygienists and educators proposed a HMPP project focused on determining if the independent practice of dental hygiene could be safe, effective, economically viable, and acceptable to the public. The application was approved by the Office of Statewide Health Policy and Development and HMPP No. 139 was officially launched in 1986. The project required 118 hours of classroom training in management and business, as well as an update on dental hygiene procedures and practices, 300 hours of a supervised residency, and, finally, 52 hours of in-service management practice.14 The final employment phase was meant to test and evaluate the concept of independent practice in a variety of settings. About 60 hygienists applied for the course. Two classes were trained with 18 participants in 1986 and 16 participants in 1987.15 Ultimately, 16 of the 34 participants went on to operate independent practices.14

The HMPP evaluation was done by a team consisting of two dentists responsible for on-site quality assurance, a dental hygiene educator, a dental school faculty member, and a health economist who managed and published the full HMPP No. 139 evaluation.15 A short history of the demonstration project documenting the trainee selection, training phases, site selection, monitoring services provided, payment sources, media coverage, and legal challenges to the demonstration project has been published elsewhere.14

The following were the HMPP’s evaluation conclusions:

-

▪

Independent practice by dental hygienists provided access to dental care, satisfied customers, and encouraged visits to the dentist.16

-

▪

The HMPP No. 139 practices consistently attracted new patients, charged lower fees, and preventive services were more available to Medicaid patients than they would be in a dental office.17

-

▪

The demonstration project produced outcomes in both structural and process aspects of care that in many cases surpassed those available in dental offices in quality, achieved high patient satisfaction, and showed no increased risk to the health and safety of the public.18

HMPP No. 139 was surrounded by a highly politicized and contentious process that created an unproductive divide between the dental and dental hygiene associations in the state. The final legislation that passed, AB 560 (Rosenthal/Perata) was co-sponsored and passed by a 77-0 margin. It represented a compromise between the various constituencies’ positions on independent dental hygiene practice. While differences of opinion about the RDHAP still exist, both the dental and dental hygiene associations have expressed formal support of RDHAP providers and a commitment to collaborating to ensure access to high quality dental care for patients.

Registered Dental Hygienists in Alternative Practice (RDHAP)

Today, a dental hygienist licensed in California with a baccalaureate degree (or the equivalent) can, after completing a board-approved continuing education course and passing a state licensure examination, practice independently in underserved settings. These settings are defined as Dental Health Professional Shortage Areas, residences of the homebound, nursing homes, hospitals, residential care facilities, and other public health settings.19 RDHAPs may independently provide all services that, as an RDH, they are licensed to provide under general supervision. RDHAPs must have a “dentist of record” on file with the Dental Hygiene Committee of California to gain licensure. This documented relationship is for referral, consultation, and emergency services.

RDHAPs can provide dental hygiene services to patients for 18 months without involvement of a dentist or physician. If an RDHAP continues to provide services to that patient he or she is required to obtain written verification that the patient has been examined by a dentist or physician licensed to practice in the state. The verification needs to contain a prescription to continue providing dental hygiene services. That prescription is then valid for two years.20

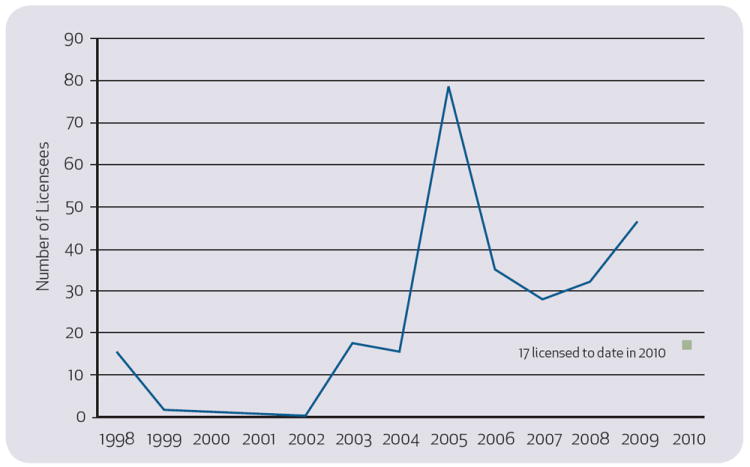

In total, 294 RDHAPs have been licensed. Currently, 287 RDHAPs are actively licensed to practice. Figure 1 shows the number of active licenses by year granted. The 16 pilot participants became eligible for licensure when the law went into effect in 1998. Additional licenses were not granted until after RDHAP education was available in 2003.

Figure 1.

Distribution of currently active RDHAP licenses by year granted in California, 2005. Data point for 2010 only represents licenses awarded up until May. The HMPP pilot participants became eligible for licensure when the law went into effect in 1998; however, no formal education was available until 2003, hence the lack of licensees between 2000-2002. Data provided by the California Dental Hygiene Committee, April 2010.

RDHAP Education Programs

One provision of the law that established the RDAHP license category was the requirement that candidates for the license complete a 150-hour dental board-approved course. The course must conform to specific educational requirements delineated in the law. There are currently two education programs for RDHAPs in California. In 2003, West Los Angeles College, a community college with a well-established dental hygiene program, opened the first training program. The same year, the California Dental Hygienists Association (CDHA) created a fund and issued a request for proposals to support the development of an online education program. The motivation was to expand the educational opportunity to dental hygienists who could not travel and attend multiple in-person sessions by offering a primarily on-line program that could be completed by hygienists on a flexible schedule and wherever they were located. The Pacific Center for Special Care at the University of the Pacific School of Dentistry (Pacific), now named the Arthur A. Dugoni School of Dentistry responded to the RFP and in 2004 opened the second RDHAP training program in California.

Today, both programs use a combination of in-person and distance education modalities. The Dugoni program has an initial and a final in-person session and the remainder of the program is delivered using Internet-based education. The West Los Angeles College program has four weekends of seminar-style continuing education on campus and the remainder is delivered through distance education. While these two training programs have produced about 250 graduates, it is noteworthy that both programs have had excess capacity since their inception.

The Current Practice of Alternative Dental Hygiene

In line with the theme of this special issue to better understand different workforce models in relation to improving access to care, the following section examines the current state of RDHAP practice along three dimensions. First, who are the individuals who become educated and licensed as RDHAPs and what is the sustainability of this pipeline? Second, what are the dimensions of the RDHAP practice model including what is working and what is not? Finally, what evidence is available regarding patient access to care under this model?

RDHAP Workforce

The practice setting restrictions surrounding RDHAP practice were not a component of the initial HMPP No. 139 pilot project, although access for underserved patients was a pilot project goal. The restrictions were a political compromise that resulted in the mandate that RDHAPs expand dental hygiene care for underserved populations in California. As a result, the individuals attracted to train and become licensed as RDHAPs are experienced, entrepreneurial, and driven by a mission to serve the underserved and improve access to care.

In 2005, a sample survey of RDHs in California provided baseline information on the 119 RDHAP providers who were licensed at the time.7 The response rate from RDHs to this survey was 73 percent (n=2776) and the response by the subcategory of RDHAPs to this survey was 92 percent (n=110). The study showed the individuals obtaining RDHAP licensure had some unique characteristics in comparison to the broader RDH workforce. The basic demographic differences are displayed in Table 1. RDHAPs were more likely than RDHs to be from an underrepresented minority population (black, Hispanic, native American), were more likely to speak a foreign language, and were less likely to have children living at home. As well, RDHAPs report having attained a higher overall level of education (in any field).

Table 1.

Demographics and Educational Attainment of Individuals in the Registered Dental Hygiene and Alternative Practice (RDHAP) Workforce in California, 2005.

| Demographics | RDH | RDHAP |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age | 44.7 | 46.9 |

| Percent female | 97.5% | 96.3% |

| Percent underrepresented minority (black, Hispanic, native American)* | 8.5% | 21.2% |

| Children at home (of any age)* | 55.5% | 41.2% |

| Can communicate with patients in a language other than English* | 26.6% | 34.7% |

| Educational level (highest degree in any field) | ||

| Certificate/associate* | 52.2% | 29.7% |

| Baccalaureate* | 43.3% | 56.4% |

| Masters/doctoral* | 4.5% | 13.9% |

Significant differences are noted at

p<0.05.

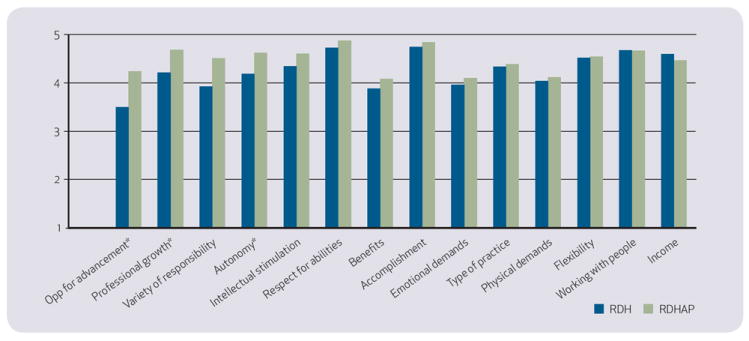

RDHAPs hold differing opinions than RDHs about issues concerning the dental professions, and in elements that contributed to their job satisfaction. These differences are displayed in Figure 2 and Table 2. The individuals with an RDHAP license were more likely to value opportunities for advancement, growth, responsibility and autonomy than RDHs, although both groups rated these attributes highly. As well, RDHAPs express stronger commitment to underserved patients and communities and improving access to care than do RDHs. Of note however, across the board, is the high percentage of both RDHs and RDHAPs who personally would like to work in different settings, advance their skills, and contribute to improving access to care.

Figure 2.

Elements that contribute to job satisfaction of RDHs and RDHAPs in California, 2005. Scale is 1-5 with 1=low contribution and 5=high contribution to job satisfaction. Significant differences are noted at *p<0.05.

Table 2.

Professional Opinions of RDHs and RDHAPs in California, 2005

| Opinions on professional issues | RDH | RDHAP |

|---|---|---|

| Would like self-employment without supervision | 39.1% | 95.9% |

| Would like general supervision only | 69.5% | 91.8% |

| Would like prescriptive authority | 64.8% | 94.9% |

| Would like to be trained to do restorative procedures | 40.1% | 70.4% |

| Is not practicing to full extent of training | 34.5% | 59.0% |

| Thinks current environment is good fit for skills | 93.9% | 87.4% |

| Would like to work outside dental office | 49.8% | 95.8% |

| Would like to be directly reimbursed | 28.1% | 88.4% |

| Desires to work with disadvantaged patients | 31.9% | 88.7% |

| Desires work with underserved community | 30.0% | 77.1% |

| Thinks improving access is important | 66.5% | 94.9% |

| Would like to interact with nondental health providers | 67.3% | 95.8% |

Percent is those who “agreed” or “strongly agreed” with the statement as it relates to them personally. All categories are statistically different at significance of p <0.01.

RDHAP Practice Activities

The 2005 study showed differences in the practice characteristics of RDHs and RDHAPs. Of the licensed RDHAPs who were practicing, 43.8 percent reported working in a residential care facility, 43.8 percent reported working with homebound patients, 31.5 percent reported working in their own private practice, and 15.1 percent reported working in schools. When comparing RDH and RDHAP practice activities, the authors found a difference between RDHAPs and RDHs in terms of the patient populations, work settings, and hours worked. These differences are displayed in Table 3. This data provides the first indication that RDHAP practices were improving access to care, particularly for minority, medically compromised, and disabled populations.

Table 3.

Patients and Practice Characteristics of Individuals in the RDH and RDHAP Workforce in California, 2005

| RDH | RDHAP | |

|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics (all patients across settings worked) | Averages | |

| Patients per day | 8.36 | 8.49 |

| Percent of patients from underrepresented minority groups | 22.2% | 24.5% |

| Percent of patients by age group | ||

| 0-1 years** | 0.1% | 0.6% |

| 2-5 years | 4.2% | 5.0% |

| 6-17 years | 12.4% | 12.3% |

| 18-64 years | 61.8% | 61.2% |

| 65+ years | 21.3% | 21.3% |

| Percent of patients medically compromised* | 16.8% | 25.8% |

| Percent of patients developmentally disabled** | 2.9% | 4.7% |

| Percent of patients mentally ill* | 2.6% | 5.6% |

| Percent of patients behavior management | 1.5% | 2.6% |

| RDH | RDHAP | |

| Practice characteristics (all practice activities inclusive of RDHAP and RDH) | Averages | |

| Work in a private dental office* | 97.5% | 75.5% |

| Hours worked per week | 34.55 | 31.77 |

| Hourly wage | $45.28 | $50.73 |

| Distribution of hours worked weekly | ||

| Patient care | 94.1% | 77.3% |

| Administration | 3.1% | 7.4% |

| Public health | 0.4% | 6.3% |

| Teaching | 1.4% | 4.6% |

| Research | 0.1% | 0.0% |

| Other | 0.8% | 4.3% |

Significant differences are noted at

p<0.05,

p<0.1.

While the baseline survey was informative in understanding the demographics of RDHs who were pursuing RDHAP practice and some general practice differences, it did not allow for a detailed analysis of RDHAP specific activities. In 2009, the authors conducted a follow-up study of RDHAPs to further investigate the practice characteristics of licensed RDHAPs. The 2009 survey received a 74 percent response rate (n=176). Of the respondents, 105 (59.7 percent) graduated from the Dugoni program, 60 (34.1 percent) graduated from WLAC, and 11 (6.2 percent) were participants in the original HMPP program. Of the survey respondents, 92.6 percent report actively practicing dental hygiene in any capacity, and of those active in practice, 72.8 percent are working as an RDHAP in California. RDHAPs report a strong intention to continue working; 58.2 percent expect to remain in the labor force for 10 or more years, with only 2.5 percent planning to drop from the labor force in the next two years.

The practice characteristics of RDHAPs are highly variable, yet a consistent theme is the use of mobile equipment to practice part time in alternative settings with patients who have no other regular source of dental care (Table 4). The most common work setting reported by RDHAPs is in residential/assisted-living facilities where on average 67.8 percent of RDHAP clients have no other source of dental care. Residences of the homebound and skilled-nursing facilities are also common work settings for RDHAPs with patients who have even fewer other options for care. In order to provide services in these settings, RDHAPs must develop formal relationships with the institutions, develop patient trust, schedule patients ahead of time, efficiently bring in mobile equipment to provide care, document the care provided and then bill either insurance or the patients individually. RDHAPs report that the work is rewarding, but ergonomically and logistically difficult. This may explain why few RDHAPs are able to do this type of practice on a full-time basis.

Table 4.

Reported Work Settings of RDHAPs and Average Percent of Patients in that Setting with no Other Source of Dental Care, in California, 2009

| Work setting (RDHAPs can have multiple settings) | Percent of RDHAPs reporting working in this setting | Average percent of patients in setting estimated to have no other source of dental |

|---|---|---|

| Residential facility/assisted living | 63.6% | 67.8% |

| Residence of homebound | 61.0% | 82.0% |

| Nursing home/skilled-nursing facility | 58.5% | 78.8% |

| Schools | 22.1% | 43.9% |

| Independent office-based practice in DHPSA | 14.4% | 51.8% |

| Other institution | 12.8% | 68.1% |

| Hospital | 9.3% | 65.1% |

| Local public health clinic | 7.6% | 73.3% |

| Home health agency | 5.9% | 71.7% |

| Community centers | 5.1% | 80.8% |

| Federal/state/tribal institution | 4.2% | 61.3% |

| Community/migrant health clinic | 4.2% | 76.0% |

| Other | 2.5% | N/A |

More than one work setting can be reported by each individual and is not indicative of full-time work, only that they provide some services in this setting.

Within the multitude of settings where RDHAPs work, they report a wide number of practice activities (Table 5). The majority of RDHAPs are providing direct patient care, for just over two days a week on average. Not all report patient care hours because some RDHAPs are employed in administrative or educational positions. In addition, RDHAPs do a significant amount of administrative work to manage their practices and case management to assist their patients. Additionally, behavior management (activities to gain cooperation for dental hygiene procedures) and public health activities are reported by more than a third of RDHAPs, and are often essential in order to bring the patients into the formal delivery system. It is clear there is not a single pathway for RDHAP practice; rather, licensees can pursue a variety of employment opportunities in addition to becoming a sole practitioner. In addition, many RDHAPs maintain some level of employment in an RDH role.

Table 5.

Practice Activities Reported by RDHAPs in California, 2009

| RDHAP practice activities | Percent of RDHAPs reporting working these types of hours | Mean hours per week of all RDHAPs | Mean hours per week of those working these type of hours |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct patient care | 95.1% | 16.4 | 17.3 |

| Patient behavior management | 51.5% | 1.9 | 3.6 |

| Patient case management | 64.1% | 2.8 | 4.4 |

| Administration | 73.8% | 5.0 | 6.8 |

| Public health activities | 36.9% | 1.6 | 4.4 |

| Teaching | 11.7% | 0.7 | 5.7 |

| Research | 3.9% | 0.1 | 3.8 |

| Other professional activities | 8.7% | 0.4 | 4.6 |

In 2009, the majority of RDHAPs (82.1 percent) reported maintaining employment in a traditional hygiene position, on average three days (24 hours) per week. Of the RDHAPs who maintain RDH employment, 77.4 percent work in an RDH position at the same location where they were employed prior to becoming an RDHAP, while 59.2 percent work as an RDH in the office of the dentist who serves as their “dentist of record” for licensure, indicating moderately strong ongoing ties between hygienists working in alternative practice and the dentists in their communities.

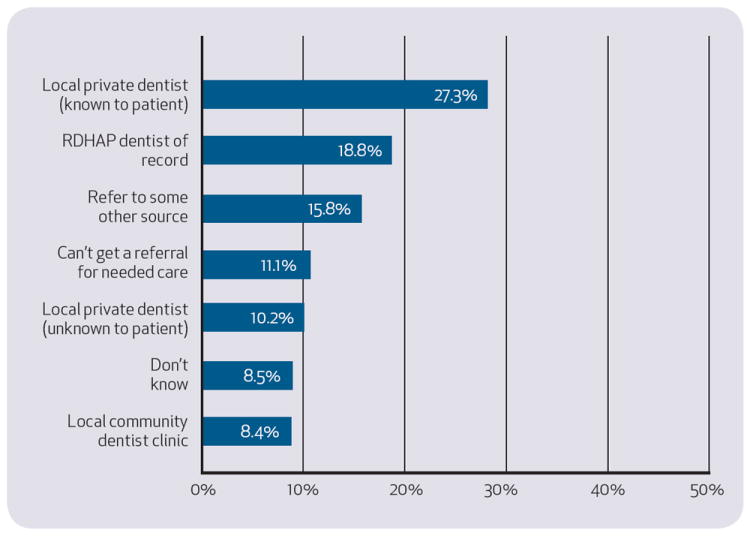

Regardless of these ties, when patients need a referral for restorative care, it appears mixed as to how easy this may be. Fifty-two point four (52.4) percent of RDHAPs report they find it “easy” or “somewhat easy” to refer their patients for dental care, while 47.6 percent report they find it “somewhat difficult” or “difficult” to find someone to accept their referrals. Only 28.0 percent of RDHAPs report that their “dentist of record” will accept regular and ongoing referrals from them. Figure 3 reports the average percentage of RDHAP patients referred to different providers in the community when they need care beyond what the RDHAP can provide. Two-thirds of referrals go to community dentists in private and public settings, yet, on average, RDHAPs cannot find needed referrals for about one in 10 of their patients (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Destination of RDHAP patient referrals for restorative or advanced care needs in California, 2009.

RDHAPs and Access to Care

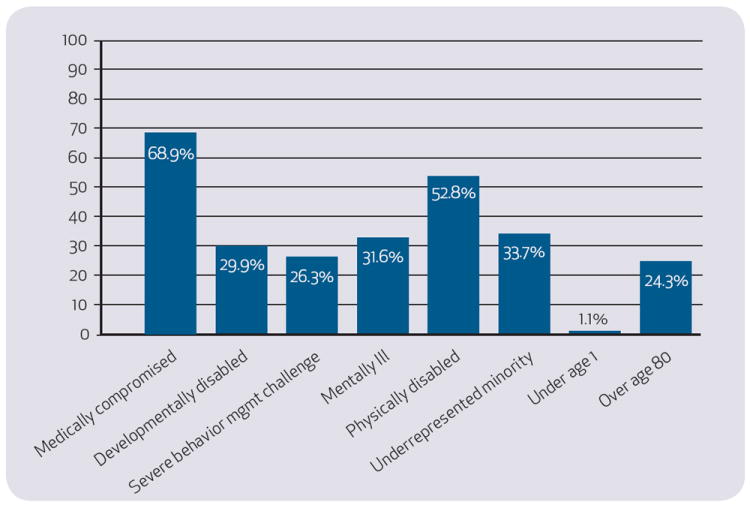

A likely factor in the difficulty finding referrals for traditional dental care is that the patient mix of RDHAPs presents some unique challenges in relation to the known limitations of the current dental care system.21 RDHAPs report difficulty communicating with one in five patients on average due to language barriers, although this ranges from zero to 98 percent. On average, 12.0 percent of RDHAP patients are under the age of five, 24.3 percent are over the age of 80, and only 11.1 percent of RDHAP patients have private dental insurance. These indicators show that RDHAPs are expanding access to preventive care through their patient care activities, as well as expanding access to restorative care through their case management and referral activities.

Given the percentages of RDHAPs that work in long-term, skilled nursing and residential care facilities it is not surprising the very high percentages of underserved patients that make up their practices (Figure 4). On average, 68.9 percent of the patients in an RDHAP practice are medically compromised, 52.2 percent are physically disabled. Almost a third (29.9 percent) on average, have a developmental disability. These patients have well-documented problems receiving dental care in the traditional system but are accessing screening, preventive care, and referrals through the work of RDHAPs.

Figure 4.

Average percent of patients in RDHAP practices by various demographic categories in California, 2009.

Discussion

As a new practice model, alternative practice dental hygiene is quite different than traditional dental hygiene practice and traditional dental practice. The financing for this model of care reported in our survey is primarily from Denti-Cal, both in patient percentages and in overall revenue, although private insurance and self-pay also contribute. The regulation of the RDHAP education program explicitly restricts the amount of education they can receive in business planning and finances, also restricting their ability to plan for and fully understand the components that go into developing an RDHAP practice during this portion of their training. (California Code of Regulations, Title 16, Division 10, Chapter 3, Article 2, Section 1073.3.) A number of RDHAPs report returning to formal education in addition to the RDHAP program to further develop their business or public health skills.

This is compounded by difficulties with payers who often refuse to recognize them as providers (although they are legal billable providers) and low fee payment streams for underserved patients. Since the July 2009 elimination of the adult benefit by Denti-Cal, RDHAPs report struggling to continue to provide services to adults formerly on Denti-Cal but have instituted measures such as sliding-fee scales to try and accommodate these clients.

The rules that regulate RDHAPs mandate where they can practice, essentially limiting their options to special and underserved populations. Testament to the difficulty any provider would face when required to practice only in the margins of the delivery system with underserved patients, RDHAPs do struggle to make their practices work. First, the logistics of providing services in the community can be challenging. As well, the ergonomics of practice in a community setting, particularly with bedbound or disabled patients, can also be challenging. While the mobile equipment can be adjusted in some cases, some of the work RDHAPs do simply cannot be done on a full-time basis due to the physical demands it places on the individual provider.

As is clear from the data presented, although the population they serve have very high needs and getting them services is difficult, RDHAPs have been able to find ways to open up access to these patients on the margins. Unfortunately the RDHAPs’ ability to refer these patients for ongoing needed dental care is still very challenging. It is likely that RDHAP choice of practice setting (within the restrictions of the law) varies by their own personal preference as well as the local economy and public health capacity, and patient demands. The educational system for RDHAPs seems to be meeting current demand and evolving to meet the needs of students to the extent possible within the restrictions outlined by the California Dental Board.

Conclusion

Since the release of the landmark 2000 Surgeon General’s Report on Oral Health the oral health care landscape has changed significantly, and with the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordability Act of 2010 at the federal level, ongoing changes are likely to impact the delivery of oral health care services.1 In the 2003 Surgeon General’s Call to Action, the key recommendation for addressing the myriad of concerns about the dental care workforce was to increase the flexibility, capacity, and diversity of the oral health workforce.22 Stakeholders have responded to this call by proposing and implementing a number of workforce innovations in the arenas of education, prevention, and practice.23

Today in California, there are 10 different provider classifications in dentistry; dentists, dental specialist (specialty board-certified DDS), dental assistants, registered dental assistants, registered dental assistants in extended function, orthodontic dental assistant permit (can be added to RDA or RDAEF), dental sedation assistant permit holder (can be added to RDA or RDAEF), registered dental hygienists, registered dental hygienist in extended function, and RDHAPs. How these providers ultimately work together in teams or in collaborative relationships among themselves and with other health care providers will create the future practice models for oral health care in California. The alternative practice of dental hygiene in California has proven to be an important innovation in successfully improving access to preventive dental care services, case management, and referral for a wide range of underserved populations in California.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Awards # U54DE019285 and # P30DE020752 from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIDCR. A number of previous funders made the data collection for this study possible, including the California Dental Association, the California Dental Hygienists’ Association, the California Program on Access to Care at the California Policy Research Center, the Health Resources and Services Administration (No. 5U76MN10001-02), the University of the Pacific, and the UCSF Center to Address Disparities in Children’s Oral Health (Pilot, NIDCR Grant No. U54 DE 142501).

Contributor Information

ELIZABETH MERTZ, Department of Preventive and Restorative Dental Sciences, senior research faculty, Center for the Health Professions, University of California, San Francisco.

PAUL GLASSMAN, Dental Practice, director of Community Oral Health Arthur A. Dugoni School of Dentistry in San Francisco.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Oral health in America: A report of the surgeon general. Rockville, Md.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pourat N. One in three young children do not get regular dental care. [Oct. 4, 2010];2008 healthpolicy.ucla.edu/pubs/files/Assembly_Dental_FS_0408.pdf.

- 3.Pourat N. Drilling down: access, affordability and consumer perceptions in adult dental health. Oakland: California Health-Care Foundation; Nov, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown LJ. Adequacy of current and future dental workforce: theory and analysis. Chicago: American Dental Association; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mertz E, Finocchio L. Improving oral health care delivery systems through workforce innovations: an introduction. J Public Health Dent. 2010;70(supplement S1):S1–S5. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2010.00179.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Dental Association, the 2006 survey of dental practice. Chicago: American Dental Association; Jul, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mertz E, Bates T. Registered dental hygienists in California: a labor market chart book (2005-2006) San Francisco: Center for the Health Professions, University of California, San Francisco; Nov, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown TT, Finlayson TL, Scheffler RM. How do we measure shortages of dental hygienists and dental assistants? Evidence from California: 1997-2005. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007 January;138(1):94–100. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2007.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McKinnon M, Luke G, et al. Emerging allied dental workforce models: considerations for academic dental institutions. J Dent Educ. 2007 November;71(11):1476–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gehshan S, Takach M, et al. Help wanted: a policymaker’s guide to new dental providers. Washington, DC: Pew Center on the states and the national academy of state health policy; May, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lobene RR, Kerr A. The Forsyth experiment: an alternative system for dental care. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, Mass.: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dugoni A. Let’ s hear it for the dental team! J Calif Dent Assoc. 1980 May;8(5):57–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robertson G. Journal of the health workforce pilot projects program. Sacramento, state of California: Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development, Healthcare Workforce and Community Development Division; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perry DA, Freed JR, Kushman JE. The California demonstration project in independent practice. J Dent Hygiene. 1994 May-June;68(3):137–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.King L. Reaching out to California’s underserved: a look at HMPP No 139. 1990 January; [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perry DA, Freed JR, Kushman JE. J Public Health Dent. 2. Vol. 57. Spring. 1997. Characteristics of patients seeking care from independent dental hygienist practices; pp. 76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kushman JE, Perry DA, Freed JR. Practice characteristics of dental hygienists operating independently of dentist supervision. J Dent Hygiene. 1996 September-October;70(5):194–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freed JR, Perry DA, Kushman JE. J Public Health Dent. 2. Vol. 57. Spring. 1997. Aspects of quality of dental hygiene care in supervised and unsupervised practices; pp. 68–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dental Hygiene Committee of California. How to become a licensed dental auxiliary in California, registered dental assistant in alternative practice (RDHAP), Application Instructions. [Oct. 1, 2010];2010 dhcc.ca.gov/applicants/becomelicensed_rdhap_appinst.shtml.

- 20.B&P. 1931. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wendling W. Private sector approaches to workforce enhancement. J Public Health Dent. 2010;70(special issue):S24–S31. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2010.00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. National call to action to promote oral health. Rockville, Md.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mertz E, Mouradian W. Addressing children’s oral health in the new millennium: trends in the dental workforce. Academic Ped. 2009 November;9(6):433–9. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]